Chromosome-scale genomes of wild and cultivated Morinda officinalis

Background & Summary

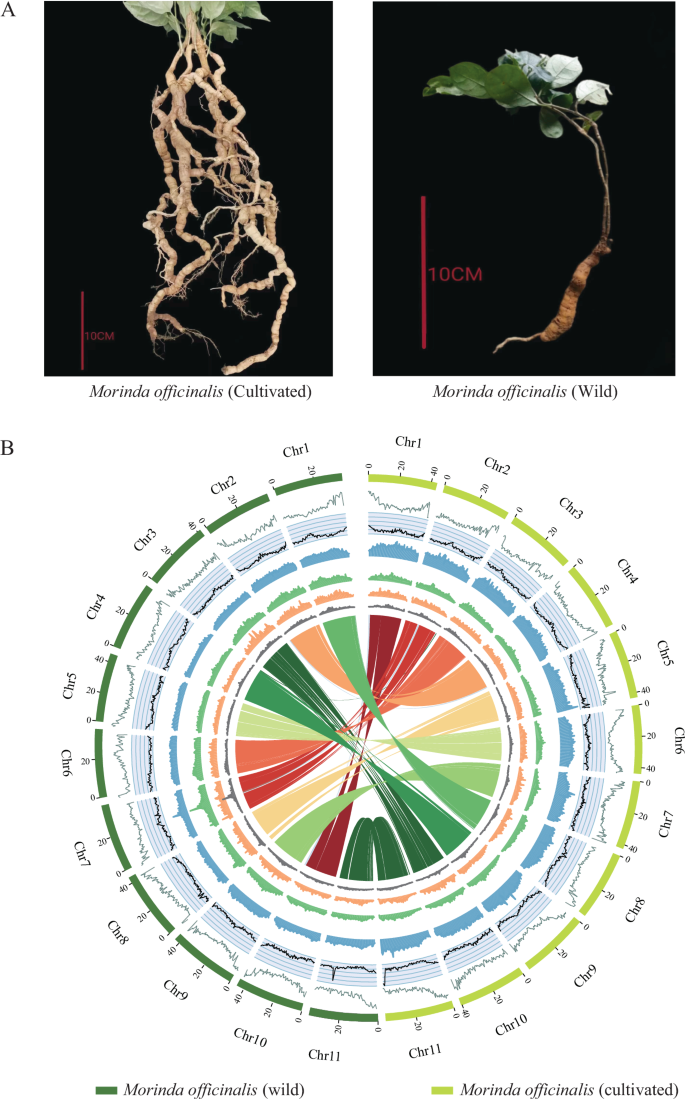

Morinda officinalis [Gynochthodes officinalis, taxonomy ID: 266091], a perennial vine belonging to the Rubiaceae family, is a renowned medicinal and edible plant native to the Lingnan region of southern China and northern Vietnam1. This species holds immense importance in traditional Chinese medicine2, where its dried roots, known as “bajitian,” are extensively used to treat a variety of ailments, including impotence, infertility, rheumatism, and arthralgia3,4,5. Interestingly, M. officinalis exists in both wild and cultivated forms, each with distinct characteristics and implications. The wild plants have a more trichome-dense leaf, a thinner vane thickness, a thinner stem, and a poorer root system compared to the cultivated species1 (Fig. 1). In contrast, the cultivated Morinda plants have less trichomes on the leaves, a thicker vane thickness, a thicker stem, and a more abundant root system than the wild counterparts. Research on phytochemical composition has revealed that M. officinalis harbors a diverse array of bioactive constituents, including anthraquinones, iridoids, flavonoids, polysaccharides, volatile oils, and various other noteworthy compounds6. The roots of wild M. officinalis populations have historically served as the primary resource for the extraction of herbal medicine2,4,6. However, due to the sharp increase in market demand, the wild resources of M. officinalis have been significantly threatened, leading to the risk of extinction3. As a result, artificially cultivated M. officinalis has become the primary source of medicinal material in China.

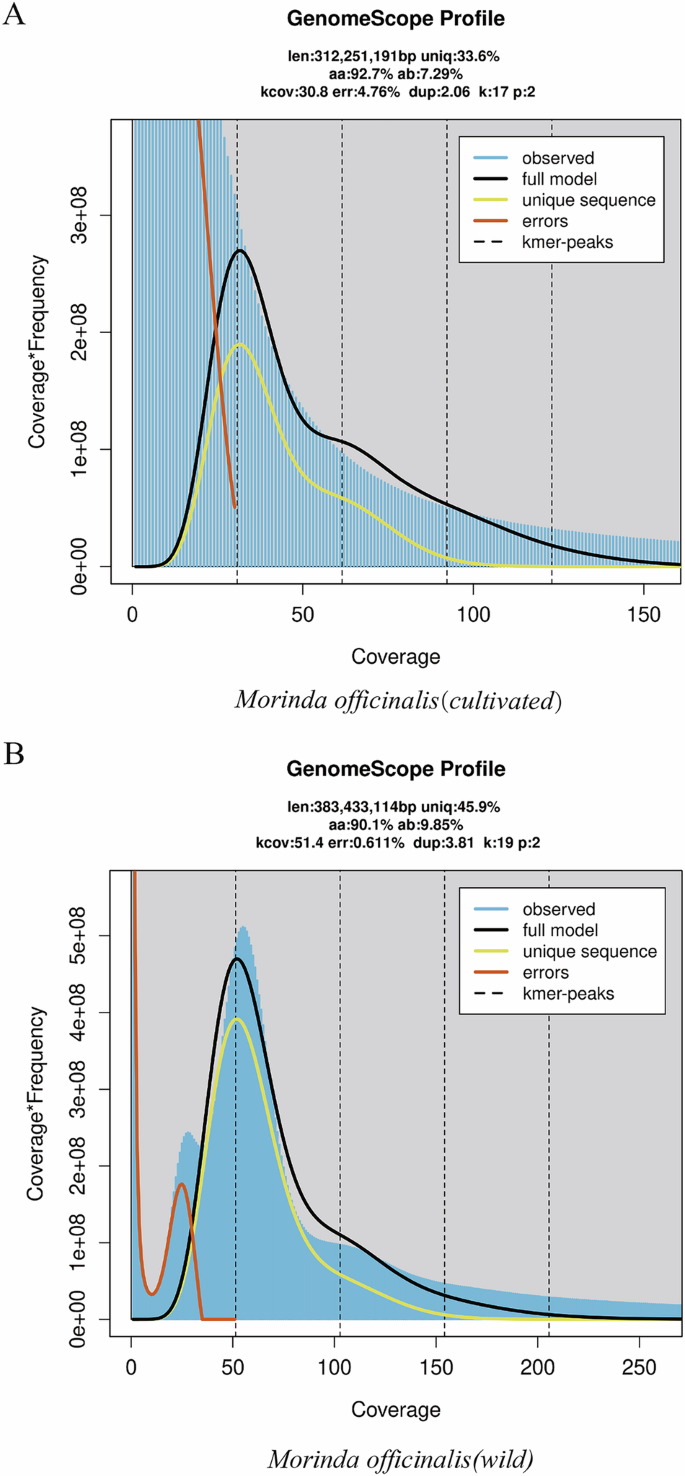

17-kmer distribution in two Morinda officinalis genomes. (A) Morinda officinalis (cultivated) (B) Morinda officinalis (wild). The dashed line indicates the expected Kmer-peaks.

Compared to their wild counterparts, the cultivated varieties of M. officinalis, such as the “Gaoji 3” cultivar, exhibit several advantageous traits, including higher yield, improved quality, and enhanced disease resistance3. These cultivated varieties have been selectively bred and optimized for commercial production, often through the integration of modern agricultural practices and biotechnological approaches. Despite the importance of both wild and cultivated M. officinalis, the genomic resources available for this species have been limited. While the genome of the cultivated variety has been previously reported3, the lack of a comprehensive genomic characterization of the wild form has hindered our understanding of the genetic mechanisms underlying the production of medicinal compounds, adaptive traits, and the evolutionary trajectories of this species. The availability of robust genome data represents an invaluable asset for investigating the genetic underpinnings of crucial traits in medicinal plants7,8,9,10,11,12. This rich resource opens up avenues for comprehensive exploration and understanding of the genetic factors governing various characteristics essential for medicinal efficacy3,7.

This study aims to address this knowledge gap by presenting the chromosome-scale genome assemblies of both wild and cultivated M. officinalis. By leveraging the power of comparative genomics, we intend to unveil the unique genomic features, identify the key genes and pathways involved in the biosynthesis of bioactive compounds, and elucidate the evolutionary adaptations that have enabled this species to thrive in its native habitats. These high-quality genomic data will not only contribute to the fundamental understanding of M. officinalis but also provide valuable resources for the genetic improvement and sustainable utilization of this important medicinal plant.

Methods

Sample preparation and sequencing

The fresh leaves of cultivated Morinda officinalis were collected from Zhaoqing City, Guangdong, China (23°23′24″N 112°20′19″E), while the wild type was originally collected from Yunfu City, Guangdong, China (22°41′3″N, 112°8′20″E), and is maintained at the experimental farm of South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China (23°9′9″N, 113°22′44″E). The DNA extraction process followed the CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method13, and subsequently underwent purification using the QIAGEN Genomic kit (Cat#13343, QIAGEN). DNA quality and quantity were assessed using complementary techniques. Spectrophotometric analysis with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) revealed DNA samples with high purity, as evidenced by OD260/280 ratios of 1.8–2.0 and OD260/230 ratios of 2.0–2.2, which are consistent with high-quality genomic DNA. Precise DNA quantification was performed using a Qubit 4.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA), ensuring accurate input for subsequent library preparation. We prepared sequencing libraries using a standardized workflow. DNA fragments were size-selected using the PippinHT system (Sage Science, USA) to obtain optimal fragment lengths, followed by end repair using the NEBNext Ultra II End Repair/dA-tailing Kit (Cat# E7546). Adapter ligation was performed using the SQK-LSK109 kit from Oxford Nanopore Technologies. Sequencing on the GridION X5 platform generated substantial sequencing data, with 12.9 Gb of raw long-reads from wild M. officinalis and 43.91 Gb from cultivated M. officinalis, providing comprehensive genomic coverage for our comparative analysis. Furthermore, the extracted DNA was subjected to digestion using MboI in accordance with the standard Hi-C library preparation protocol, and was subsequently sequenced on the BGI-DIPSEQ platform, generating 79 and 72 Gb of data for both cultivated and wild M. officinalis, respectively (Table S1). For the RNAseq experiment, TIANGEN Kit was used for total RNA extraction from the roots. After a quality control check, library construction and sequencing were performed on the BGI-DIPSEQ platform which generated 30.67 Gb and 66.33 Gb raw data for wild and cultivated M. officinalis, respectively (Table S2).

Estimation of genome size

The short DNA reads underwent preprocessing to remove adapter sequences, duplicate reads, and low-quality reads using trimmomatic (v3.0)14, employing the following parameters: (adapter:2:30:10:8:true LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:50). Subsequently, the resulting clean data were utilized for genome size estimation through kmerfreq. 16 bit (Version 2.4) and GCE software (refer to Fig. 1 and Table S3)15. The analysis revealed estimated genome sizes of 383 Mb for wild M. officinalis and 312 Mb for cultivated M. officinalis (Table 1).

De novo genome assembly and evaluation

The nanopore long reads obtained from both wild and cultivated M. officinalis were assembled using NECAT16. Subsequently, all assemblies underwent polishing with short reads using NextPolish software17. Finally, the genomes were aligned to resolve contig overlaps using purge dups (v.1.2.3)18, utilizing default parameters. This process yielded genome assemblies of 423 Mb and 425 Mb, with scaffold N50 lengths of 5.91 Mb and 10.99 Mb for wild and cultivated M. officinalis, respectively (as detailed in Table 1 and Table S3).

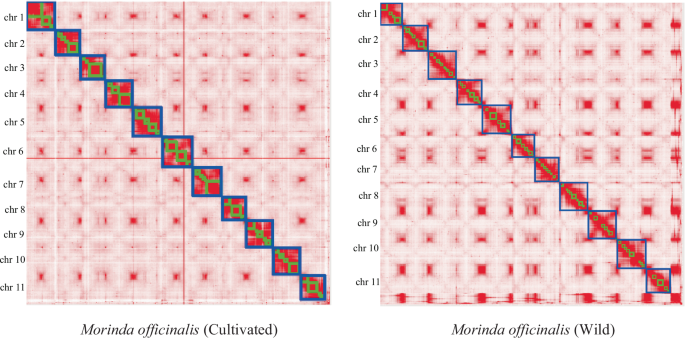

Furthermore, we utilized Hi-C data to align the contig assemblies onto chromosomes. The Juicer software19 facilitated the extraction of uniquely mapped and non-PCR duplicated Hi-C contact reads, followed by integration of the assembled genome into the pseudochromosome-level assembly using 3D-DNA20. Subsequently, the Hi-C assembly output was visualized using Juicebox and manually refined based on the Hi-C contact map. This process resulted in pseudochromosome-level assemblies totaling 412 Mb and 421 Mb, anchored to 11 chromosomes in wild and cultivated M. officinalis, respectively, with scaffold N50 lengths measuring 38.12 Mb and 39.18 Mb, respectively. Moreover, over 96.5% and 97.4% of scaffolds were successfully integrated into the pseudochromosomes of each species, respectively, consistent with the reported chromosome number3 (Figs. 2, 3, Table 1, Table S4).

Circos plots of two Morinda officinalis genomes. (A) Image showing the morphological attributes of cultivated and wild M. officinalis (B) Circos plot of M. officinalis (cultivated) and M. officinalis (wild) genome. Concentric circles from outermost to innermost show (A) chromosomes and megabase values, (B) gene density, (C) GC content, (D) repeat density, (E) LTR density, (F) LTR Copia density, (G) LTR Gypsy density and (H) inter-chromosomal synteny (features B-G are calculated in non-overlapping 500 Kb sliding windows).

Hi-C map of the M. officinalis (cultivated) and M. officinalis (wild). Map showing genome-wide all-by-all interactions. The map shows a high resolution of individual chromosomes that are scaffolded and assembled independently. The heat map colors ranging from light pink to dark red indicate the frequency of Hi-C interaction links from low to high (0–10).

Repeat annotation

We employed a combination of de novo and homolog-based approaches to detect repeat elements within the genomes of five species. For de novo prediction, LTR_FINDER21 and RepeatModeler22 were utilized to identify repeat elements, followed by the construction of a non-redundant library for repeat element identification using RepeatMasker23. As for the homolog-based methods, TRF was utilized to detect tandem repeats, and RepeatMasker was employed to search for repeat elements against RepBase (v.21.12). Overall, 51% and 67.16% of the genome sequences were recognized as repetitive sequences in wild and cultivated M. officinalis, respectively (detailed in Table 2 and Table S5). Notably, long terminal repeats (LTRs) constituted the highest proportions, accounting for 34.29% and 32.77% in wild and cultivated M. officinalis, respectively.

Protein-coding gene prediction and Non-coding RNA annotation

The prediction of protein-coding genes was conducted using the BRAKER2 pipeline24, resulting in the discovery of 31,308 and 29,528 protein-coding genes in wild and cultivated M. officinalis, respectively (as outlined in Table 2 and Table S6). Notably, more than 97.1% and 96.4% of these genes exhibited complete BUSCOs in the respective species (as indicated in Table S8). All protein-coding genes underwent BLAST analysis against NR, SwissProt, KOG, and KEGG databases, employing a cutoff E-value of 1e-05 (Figs S1–S4).

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes were identified by querying against the plant rRNA database using BLAST. MicroRNAs (miRNA) and small nuclear RNA (snRNA) were searched against the Rfam 12.0 database. Additionally, tRNAscan-SE was utilized for tRNA detection25. This comprehensive approach led to the identification of a total of 2021 and 2291 non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in wild and cultivated M. officinalis, respectively. Notably, the number of rRNAs in the cultivated variety was found to be twice as high as in the wild type (Table S8).

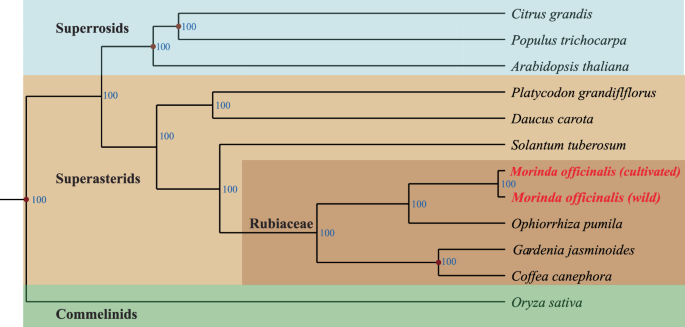

Confirming the phylogenetic position of Morinda officinalis

To show the phylogenetic positions of wild and cultivated Morinda officinalis, in comparison with 12 representative plant species (including and other published genomes of Citrus grandis, Populus trichocarpa, Platycodon grandiflflorus, Daucus carota, Solantum tuberosum, Ophiorrhiza pumila, Gardenia jasminoides, Coffea canephora, Oryza sativa, and Arabidopsis thaliana) (Table S9), the gaps were filtered, and the sequences of each of the 317 single-copy orthologs were extracted and aligned using MAFFT (v 7.310)26. Following alignment, the protein-coding sequences of each species were concatenated to form a supergene sequence. Subsequently, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-Tree (v 1.6.1)27, employing the parameters ‘-bb 1000 -alrt 1000’ (Fig. 4).

Phylogenetic position of M. officinalis. The phylogenetic tree constructed by IQtree with ‘-b 100’ using 317 single copy orthologues of two Morinda species and eight other representative plant species. The numbers below the middle of each branch represent the bootstrap values.

Data Records

All the sequencing data are deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) database under the BioProject accession number PRJCA03238728. The Chromosome-scale genome assemblies are deposited to the NCBI under the accession number GCA_046128155.129 and GCA_048301565.130 for the cultivated and wild M. officinalis, respectively. All the raw and assembled sequencing data, including the chromosome-scale genome assemblies are also deposited to CNGB Sequence Archive (CNSA) of China National GeneBank DataBase (CNGBdb) under accession number CNP000485731. The annotation files are available via Figshare32.

Technical Validation

The completeness and contiguity of the genomes were evaluated using BUSCO (V3.0.2)33 software with the Embryophyta odb10 dataset. The analysis revealed that 97.3% and 97.5% of complete embryophyte BUSCOs were present in the genome assemblies of wild and cultivated M. officinalis, respectively (as detailed in Table 1 and Table S10). Furthermore, DNA short reads were mapped to the genomes using BWA (v.2.21), demonstrating a high mapping rate (>99%) (Table S11).

In addition, the contiguity of the genome assembly was assessed using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI), which evaluates the assembly of LTR sequences. Initially, LTRharvest34 was employed to detect LTR sequences with specific parameters. These results were then combined with the output from LTR_FINDER. Subsequently, LTRretriever (v.2.8)35 was utilized to identify high-confidence LTR retrotransposons using default settings. The LAI score was calculated based on these results, yielding values of 13.44 and 12.33 for wild and cultivated M. officinalis, respectively (refer to Table 1). The high quality, contiguity, and completeness of the assembled genomes were corroborated by multiple lines of evidence36.

Responses