Systemic lupus erythematosus: updated insights on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention and therapeutics

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), canonically defined as an auto-immune disorder, can be considered as a chronic inflammatory illness with clinical manifestations encompassing various organs such as the blood vessels, brain, lungs, skin, kidneys and joints due to polymorphic biological alterations.1 It affects approximately 3.4 million people worldwide, with 400,000 individuals being newly diagnosed each year.2,3 It most commonly occurs among women between puberty and menopause,4 and individuals of the African origin have a higher risk of developing SLE.5,6,7 According to a 2023 global epidemiology study of SLE, Poland, the United States, Barbados, and China showed the highest SLE incidence.2 Though still with an unclear disease of origin, the chance of developing SLE is believed to be associated with genetic factors, epigenetic factors, environmental triggers, and hormonal factors.8

SLE can be diagnosed from the perspectives of disease onset and disease activity. These can be assessed using varied types of evaluation metrics such as the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria and the SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI). Besides, SLE is typically accompanied with increased risks of developing multiple types of comorbidities, with cancer screening being recommended by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)9 and cerebrovascular disease being alarmed among female SLE patients by the American Heart Association.10

SLE is caused by an autoimmune reaction involving both the innate and adaptive immune systems, where an abnormal immune response is directed to nucleic acid-containing cellular particles. The over production of antibodies targeting these nucleic acids, known as antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), is characteristic of SLE.8 Besides, the anti-Smith (anti-Sm) antibody, which is an auto-antibody directed against a component of the spliceosome, is highly specific to SLE, with 20-40% SLE patients versus approximately 1% healthy individuals carrying them.11

Various types of agents have been used for SLE therapeutics, ranging from cytokines, antibodies, hormones, inhibitors, antagonists, to the transfusion of fresh plasma and stem cells. Importantly, while several drugs initially designed for treating other pathological conditions have been shown effective in treating SLE such as the use of the anti-malaria agent hydroxychloroquine as a SLE therapeutic, a plethora of medications have been reported capable of inducing SLE. Examples of this kind include anti-arrhythmic agents such as procainamide, broadspectrum antibiotics such as minocycline, vasodilators such as hydralazine and methyldopa, and antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine. These have unanimously complicated our understandings on the appropriate therapeutics of SLE, rendering it necessary and urgent to delve into the molecular mechanisms driving SLE pathogenesis and classify current therapeutics accordingly by their mechanisms-of-action. This may guide us towards effective management of SLE and, hopefully, help us identify the pivotal signaling axis for the establishment of innovative targeting strategies.

Following the introduction of some basic knowledge of SLE including the history and epidemiology, this review characterized three key determinants of SLE pathogenesis by their mechanisms-of-action, i.e., over-activated immune response, skewed cytokine microenvironment homeostasis, impaired debris clearance machinery; summarized current understandings on SLE diagnosis by disease onset, activity and comorbidity; introduced risk factors predisposing SLE at the genetic, epigenetic, hormonal and entrinsic levels; and classified current SLE preventive strategies and therapeutics by the identified working mechanisms. Our review not only provides comprehensive information on SLE so far available, but also proposes fresh insights on our current understandings of SLE, with a focus on its prevention and therapeutics.

Basics of SLE

Research history of SLE

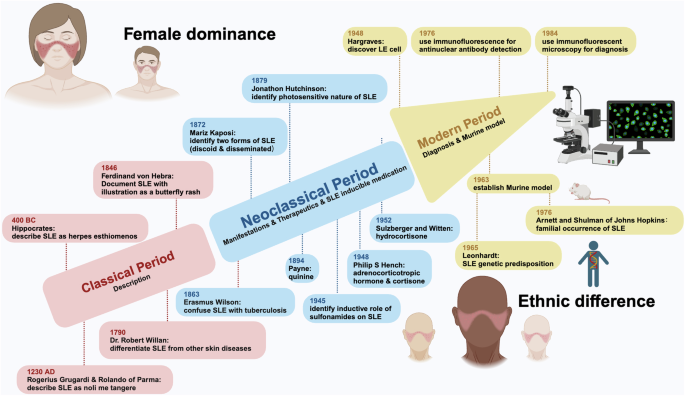

The history of SLE can be dated back to 400 Before Christ (BC) and divided into three periods, i.e., the classical period, the neoclassical period, and the modern period. The classical period, cornerstoned by Hipocrates who firstly described the possible ulcers of SLE as herpes esthiomenos, identified and documented SLE as a cutaneous disorder.12 The neoclassical period witnessed the manifestations and therapeutics of SLE. During this period, Ferdinand Hebra reported the facial rash associated with SLE as a butterfly rash with illustrations; and Jonathon Hutchison noted the photosensitive nature of SLE, among other milestones. Regarding SLE therapeutics, quinine was firstly used by the Physician Payne, followed by the use of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisone by the physician Philip S Hency, and later hydrocortisone by Sulzberger and Witten. In addition, the inductive role of medications such as sulfonamides on SLE was found during this period.12 The modern era was heralded by the discovery of the lupus erythematosus (LE) cell (a bone marrow phenomenon involving the phagocytosis of nuclear material by polymorphonuclear leukocytes) and characterized by rapid scientific advances over the past 60 years. Before the discovery of LE cell by Hargraves in 1948, the Wasserman test for syphilis was used for SLE diagnosis. The use of immunofluorescence for ANA detection followed. The establishment of the murine models has substantially advanced the scientific field related to SLE, leading to the discovery of the genetic predisposition of SLE by Leonhardt and the familial association of SLE by Arnett and Shulman of Johns Hopkins.12 Thanks to the contributions of these scientists made along the history of SLE researches, the lifespan of SLE patients has now been extensively extended from no longer than 5 years after the initial diagnosis to living with illness12 (Fig. 1).

History and etiological features of SLE. The history of SLE studies is divided into three periods, i.e., classical period, neoclassical period, modern period. The classical period is characterized by ‘SLE description’, with critical events being ‘description of SLE as herpes esthiomenos by Hipocrates’, ‘description of SLE as noli me tangere by Rogerius Grugardi & Rolando of Parma’, ‘confusion of SLE with tuberculosis by Erasmus Wilson’, ‘description of SLE as skin disorders by Robert Willan’, and ‘differentiation of SLE from other diseases by Willan’. The neoclassical period is characterized by ‘SLE manifestions, therapeutics, and identification of the inductive role of some medications on SLE’, with representative events being ‘documentation of SLE with illustrations as a butterfly rash by Ferdinand Hebra’, ‘identification of the photosensitive nature of SLE by Jonathon Hutchison’, ‘definition of the two forms of SLE, i.e., discoid and disseminated SLE by Mariz Kaposi’, ‘use of quinine b Payne and use of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisone by Philip S. Hency’, ‘use of hydrocortisone by Sulzberger and Witten’, and ‘identificaton of the inductive role of sulfonamides on SLE’. The modern period is characterized by ‘SLE diagnosis and establishment of murine model’, with milestone events being ‘discovery of lupus erythematosus (LE) cell by Hargraves’, ‘use of immunofluorescence for antinuclear antibody (ANA) detection’, ‘use of immunofluorescent microscopy for diagnosis’, and ‘establishment of murine model’, where following murine model establishment, the genetic predisposition and familial occurrence of SLE were consecutively recognized

Epidemiology of SLE

SLE is a heterogeneous disease occurring frequently among women and least common among children.8 SLE most commonly afflicts women between puberty and menopause,13 where the female/male ratio shifts from 3/1 in children to about 9/1 or even 15/1 among adults between puberty and menopause14,15 (Fig. 1).

SLE is associated with an increased risk of premature mortality that has improved over the past 30 years,16 and the risk conveys an ethnic-dependent difference.15,17 The development of lupus nephritis (LN), a SLE-associated renal complication, is considered a strong predictor of an increased mortality risk. SLE patients of African, Chinese and Hispanic origins have shown an increased risk of developing LN18,19 and thus enhanced mortality.18,19,20 Besides mortality, the disease incidence, prevalence, age-of-onset, and morbidity of SLE also vary greatly among regions.17 For instance, the annual incidence and prevalence rates of SLE in the United States each varies from 2 to 7.6 and from 19 to 159 per 100 000 individuals, respectively, for people of different racial backgrounds.5,6 In particular, individuals of the African origin, particularly those who have migrated to America or Europe, exhibit a higher incidence and prevalence, earlier age at the disease-of-onset as compared with those of the north European origin5,6,7 (Fig. 1). Asian have a lower regional risk of developing SLE than people from the United States,21,22 but the prevalence of SLE among people carrying the Chinese background has been reported to be increasing.23 Such ethnic differences among SLE patients may be explained by their different socioeconomic backgrounds, distinct perceptions on the condition, varied risks of getting infection or developing comorbidities especially cerebrovascular diseases, imbalanced availability of the medical resources, and non-uniform adherence to the therapeutics.3,16,17,24

SLE pathogenesis by mechanisms-of-action

SLE is characteristic of increased presentation of autoantibodies such as ANA, anti-Sm, anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody, antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies, and anti-β2-glycoprotein (aβ2GPI) antibodies,1 which even occur years prior to the clinical onset of SLE.25 Being the primary effectors of SLE inflammation and associated damage,26 autoantibodies form immune complexes (ICs) and deposit on multiple organs such as kidney, skin and central nervous system to induce local inflammation.26,27 Antibodies are produced by plasma cells (PCs) and plasmablasts, the terminally differentiated B cells.28 As the precursors of PCs and important antigen-presenting cells (APCs),29,30 B cells loose tolerance to autoantigens31 and may present them to T cells in SLE patients followed by the activation of Th cells. Stimulated Th cells activate B cells and contribute to their differentiation through clusters of differentiation 40 ligand (CD40L)/CD40 interactions.32 Activated B cells move to germinal centers (GCs) with the help of Tfh cells and follicular dendritic cells (DCs), where B cells generating antibodies with high antigen affinity are expanded and differentiate into the memory B cells (MBC) and antibody-producing PCs.33

Over-production of immunoactivating materials

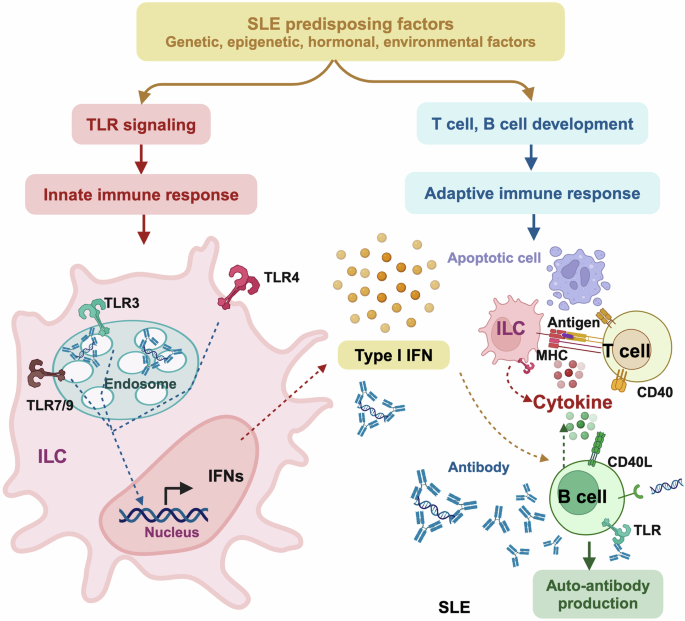

Interferons (IFNs) are cytokines with pleiotropic roles in immune regulation that can be categorized into type I, II, and III based on sequence homology.34 Type I IFNs represent the largest IFN family comprised of IFNα, IFNβ, IFNω, IFNκ, and IFNε; the type II family includes solely IFNγ; and the type III family contains IFNλ1, IFNλ2, IFNλ3, and IFNλ4.35 Out of the three families of IFNs, type I IFNs play an immunomodulatory role that bridges the gap between the innate and adaptive immune systems.35 That is, the expression of type I IFNs is activated on the trigger of nucleic acids via intracellular pathways such as Toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated signaling; the binding of type I IFNs to their receptors activates the intracellular signaling cascade involving the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) axis that leads to stimulated effectors of the innate and adaptive systems.35,36,37

There has been a well-established positive association between type I IFNs and SLE. Specifically, the blood levels of type I IFNs were documented to be elevated in approximately 50% of SLE patients.38 An even greater percentage of SLE patients were estimated to carry over-represented expression of genes involved in type I IFN-mediated signaling in their peripheral blood cells.39,40

Type I IFNs are generated in response to, primarily, the activation of nucleic acid-binding pattern recognition receptors such as the endosomal TLR3/4/7/9, the cytosolic sensor cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate (cGMP-AMP) synthase (cGAS), and the ribonucleic acid (RNA)-sensor retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG) I like receptors (RLRs)-mitochondreal antiviral signaling protein (MAVS).41 These nucleic-acid sensing pathways are chronically over-activated in many SLE patients, with the pathogenesis roles of TLR7 in SLE being well-established.42 For instance, over-activation of the cGAS-stimulator of IFN genes (STING) pathway has been shown to be crucial in autoimmunity and SLE pathogenesis.40,43

In addition, events altering nucleic acid metabolism may also trigger type I IFNs production, where the essential roles of cytosolic nucleic acid sensors played in SLE have been well characterized.44,45 For instance, ultraviolet (UV) light exposure has been shown capable of enhancing type I IFNs response both locally and systemically, with the evidence being obtained from both the animal model and from the clinics46 (Fig. 2).

Mechanisms-of-action driving SLE pathogenesis via over-activating immune response. SLE predisposing factors including genetic, epigenetic, hormonal and environmental factors can function as or induce the production of immunoreactants to trigger Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling in the innate immune system for enhanced generation of type I interferon (IFN), or modulate the development and maturation of T and B cells in the adaptive immune system for over-production of auto-antibodies. Type I IFN functions as the hub bridging the innate and adaptive immune systems. Specifically, type I IFN is produced from innate lymphoid cells (ILC), and directly triggers B cell activation to overtly produce auto-antibodies that ultimately contribute to SLE pathogenesis. Besides producing type I IFNs, ILCs can also present antigens to T cells via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) to activate T cells that express CD40L that interacts with B cells via the CD40L-CD40 bridge for enhanced auto-antibody production

Type I IFNs are central to the activation of both the innate and the adaptive immune systems. Specifically, by interacting with their receptors, type I IFNs induce signaling through the JAK/STAT pathway followed by the transcription of IFNs-responsive genes that encode the ‘IFN signature’ for activated immune response. On the other hand, type I IFNs can directly activate DCs for enhanced presentation of antigens to T cells, where T cell activation and polarization are important to prime B cell differentiation. Activated B cells then produce auto-antibodies that, once over-produced without timely clearance, deposit in organs and cause tissue damages, the process of which is facilitated by the interactions between CD40 and CD40L40 (Fig. 2).

Skewed cytokine microenvironment

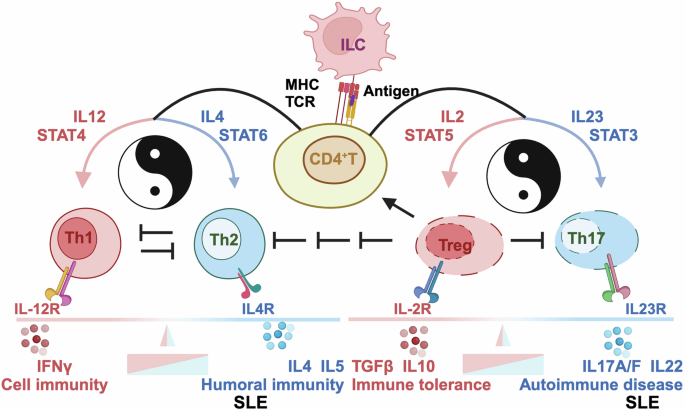

There are two types of T cells, i.e., αβ+ and γδ+ T cells, and αβ+ T cells can be further classified into CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. While CD8+ T cells take on the cell-killing activity,47 CD4+ T cells are T helper (Th) cells capable of promoting CD8+ T cell development and B cell differentiation as well as antibody synthesis.48,49 CD4+ T cells can be roughly subdivided into Th1, Th2, Th17 and regulatory T (Treg) cells, based on their distinct cytokine profilings.50 Th1 cells produce, primarily, IFNγ, interleukin (IL)12, IL2, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, IL1β, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF); Th2 cells secrete IL4, IL5, IL6, IL10, IL13, among others;51 Th17 cells are featured by expressing IL17A, IL17F and IL22;52 and Tregs secrete transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), IL10, IL34, IL35 etc.53,54 These cytokines form the cytokine microenvironment to support the amplification of a self-directed immune response, perturbed homeostasis of which may lead to disease syndromes including SLE.

With our incremental understandings on the heterogeneity of Th cells and their roles in regulating cytokine homeostasis, more subcohorts of Th cells such as T follicular helper (Tfh), T peripheral helper (Tph), follicular regulatory T (Tfr) cells have been consecutively identified, some of which hold essential roles in SLE.55,56,57,58,59 For instance, expansion of Tfh and Tph is a prominent feature of SLE,58 and Tfr cells can suppress B cell activation via disrupting the recognition and interaction between Tfh cells and B cells.55 B cells have been previously considered to be stimulated by Th2 cells but are now considered primed by Tfh cells. Thus, Tfh and Tph function in the Th2 linkage towards activated B cells and enhanced SLE severity, Tfr cells act as the switch-off button suppressing the activity of Tfh.60 We focus on the Th1/Th2 and Treg/Th17 pairs that build up the conceptual framework controlling cytokine homeostasis, where T cell subsets involved in fine-gained regulations within this framework such as the modulatory roles of Tfh were not comprehensively covered or thoroughly discussed here.

Besides CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, double-negative (DN) T cells (a unique subset of T cells lacking both CD4 and CD8 co-receptors) also play a significant role in SLE pathogenesis. DN T cells are formed by T lymphoid progenitor cells never traveled through thymus, by T lymphoid progenitor cells traveled through thymus but lack further development into CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, and by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells with down-regulated CD4 or CD8 co-receptor.61 DN T cells comprise 1-3% of human T cells and are of high heterogeneity. There exists at least five DN T cell cohorts, i.e., helper DN, cytotoxic DN, innate DN, resting DN, and intermediate DN.62 DN T cells may be pro-inflammatory such as IL17-producing DN T cells63 and anti-inflammatory such as IL10-producing DN T cells.64 The roles so far reported on DN T cells in SLE are largely pro-inflammatory. Specifically, the amount of DN T cells was considered to be positively correlated with SLE activity;65,66 DN T cells conveyed a positive impact on B cell-mediated antibody production by stimulating the release of IL4, IL17 and IFNγ;67 and enhanced DN T cell apoptosis as a result of inhibited neddylation attenuated lupus progression in murine models.66 Though the significance of DN T cells in SLE pathogenesis is not negligible, they are exempted from the focus of this section given the shared cytokines (such as IL4, IL17 and IFNγ) they produce with different CD4+ T subsets, complex functional plasticity (having both helper and cytotoxic DN cohorts) and small percentage.

Th1/Th2 imbalance

Cytokines produced by Th1 cells are largely pro-inflammatory, and those generated by Th2 cells are primarily anti-inflammatory.68 Numerous evidence has suggested that abnormal T cell differentiation to Th2 dominance can lead to B cell hyper-activation that contributes to immune disorders including SLE pathogenesis.51 The selective development of Th1 and Th2 cells is primarily driven by the cytokine microenvironment among other influential factors such as antigen dose, affinity of antigens, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) haplotypes and co-stimulatory factors. Among other cytokines, IL12 and IL4 dictate the fate of Th cells to the Th1 or Th2 linkage, respectively. While IL12 drives Th1 cell differentiation through STAT4 signaling that leads to up-regulated IFNγ and down-regulated IL4/IL5 for amplified Th1 proliferation, IL4 induces Th2 clonal expansion through STAT6 that results in up-regulated levels of IL4/IL5 and down-regulated IFNγ expression for augmented Th2 differentiation (Fig. 3).69

Mechanisms-of-action driving SLE pathogenesis via skewing cytokine microenvironment. On antigen presentation to CD4 + T cells through T cell receptor (TCR) by innate lymphoic cells (ILC) via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) from the innate immune system, CD4+ T cells are activated and can differentiate into distinct T cell subsets such as T helper 1 (Th1), T helper 2 (Th2), T helper 17 (Th17) and T regulatory (Treg) cells, the direction of which is dictated by the cytokine milieu of the microenvironment. Specifically, when IL12 is enriched in the environment, T cells favor Th1 polarization, the process of which involves STAT4 signaling that leads to up-regulated IFNγ and down-regulated IL4/5; when IL4 is enriched in the milieu, T cells are triggered for Th2 clonal expansion via STAT6, resulting in up-regulated IL4/5 expression and down-regulated IFNγ level. On the other hand, IL23, among others, drives T cell plasticity towards Th17 phenotype, the process of which involves STAT3 signaling; and IL2, out of other cytokines, inhibits Th17 generation but promotes Treg generation, where STAT5 plays a role. The balances between Th1 and Th2 cells dictates the preference towards cell immunity and humoral immunity, respectively, as regulated by IFNɤ and IL4/5, respectively. The homeostasis between Treg and Th17 cells determines whether the system goes for immune tolerance (that can cause chronic infectious diseases including cancers) or immune activation (that can lead to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases including SLE), as regulated by TGFβ, IL10 (among other cytokines produced by Treg cells) and by IL17A, IL17F, IL22 (out of other cytokines generated by Th17 cells). These subsets of CD4+ T cells cross-regulate among themselves. In particular, Th1 and Th2 cells suppress the expression of each other, Treg cells reduce the levels of Th1, Th2, Th17 cells, and activates that of CD4+ T cells. Only representative cytokines are listed in this Figure. that do not exclude the existence of others

Th17/Treg imbalance

The imbalance between pro-inflammatory Th17 cells and immuno-suppressive Tregs underlies the pathogenesis of SLE.70,71,72 The proportion of Th17 cells is higher in SLE patients, the content of which is positively correlated with SLE severity.73 Tregs play an important role in maintaining the immune tolerance, reduced levels or activities of which are tightly associated with the onset and progression of SLE74,75,76 (Fig. 3).

The subsets of Th17 cells and Tregs have distinct metabolic patterns. While Th17 cells are mainly powered by glycolysis, the energy supply of Tregs largely relies on fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation.77 Accordingly, glycolysis deprivation was found to impair Th17 cell differentiation but support the growth of Tregs;78,79,80,81 and impaired fatty acid oxidation was associated with increased Th7 cell linkage yet diminished Tregs development.82 Thus, switching energy supply from relying on carbohydrates to lipids (low-carb or ketogenic-diet) may be a dietary recommendation for SLE patients.

Impaired debris clearance machinery

The pathogenesis of SLE is associated with the failure of removing self-reactive clones of T and B cells. Under normal conditions, an immune response against self-antigens (i.e., anergic responses) can be suppressed by the immune system; however, when this debris clearance machinery is impaired, the ICs (comprised of, e.g., nucleic acids, nucleic acid-binding proteins, autoantibodies directed against those components) may form and initiate the onset of inflammation and organ damage; perpetuation of damage occurs when the ICs further amplifies the immune system followed by the trigger of downstream signals that induce pro-inflammatory mediators such as IFNα, leading to or aggregating the pathogenesis of SLE.

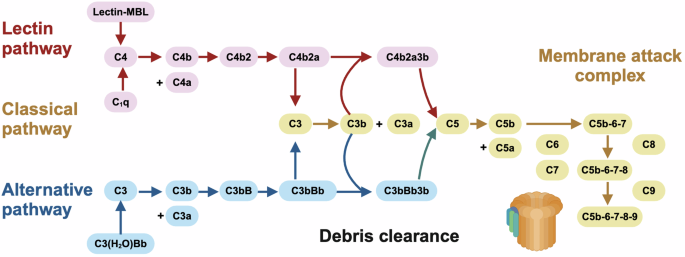

The complement system is centered at the core of the immune system mediating a cross-talk between the innate and adaptive immune responses. The complement system has been implicated in diverse biological processes in mammals including, e.g., modulation of the immune tolerance, and autoimmune diseases. Dynamic homeostasis between the activation and inhibition of the complement system is required to maintain human health. While hyper-activated complement system may lead to excessive inflammation and tissue damage, hypo-activation of the complement machinery may impair debris clearance and lead to autoimmune disorders including SLE83 (Fig. 4).

Mechanisms-of-action driving SLE pathogenesis via impairing debris clearance machinery. There are three mechanisms to initiate the complement cascade for debris clearance, i.e., the classical, lectin, and alternative pathways. In the classical and lectin pathways, the complement system is triggered by the binding of the antibody complexes to C1q of the C1 complex and the binding of foreign carbohydrate moieties to mannose binding lectin (MBL) or ficolin, respectively, which converge to the cleavage of C4 to C4b and C4a followed by the generation of one C3 convertase, i.e., C4b2a. In the alternative path, the complement system is activated via spontaneous hydrolysis of C3 into C3b and C3a by the convertase C3(H2O)Bb followed by the formation of another C3 convertase, i.e., C3bBb. Under the cleavage of C4b2a or C3bBb, C3 becomes C3b and C3a. Following this, C3b binds to C4b2a or C3bBb to form C4b2a3b or C3bBbC3b which are C5 convertases capable of hydrolyzing C5 into C5b and C5a; and C5b can initiate the cascade of forming the membrane attack complex (MAC) capable of generating pores in the membranes of pathogens or targeted cells. While C3 activation fragments such as C3b participate in the cleaning of cellular debris to avoid overt activation of the immune system that is favorable for halting SLE pathogenesis, overt production of MAC may promote SLE pathogenesis via causing cell death and generating more immunoreactants

The complement cascade is activated to initiate the proteolytic cleavage of complement proteins into fragments that relay signals to neighboring cells and leukocytes by being deposited onto the targets or released into the extracellular fluid. There are three mechanisms, so far elucidated, to activate the complement system, i.e., the classical, alternative, and lectin pathways.83 In the classical pathway, the complement system is triggered by the binding of the antibody complexes to C1q of the C1 complex. In the alternative path, the complement system is activated via spontaneous hydrolysis of C3. In the lectin pathway, the system is stimulated via the binding of foreign carbohydrate moieties to mannose binding lectin (MBL) or ficolin. All pathways converge to the generation of C4b2a or C3bBb, the cleavage of C3, and the amplification loop. C3b, cleaved from C3, then promotes the formation of C4b2a3b in the classical/lectin pathways or C3bBb3b in the alternative pathway. C4b2a3b or C3bBb3b activate C5 to form the membrane attack complex (MAC) that takes on the action through direct lysis of the target cells. Perturbed activation or availability of any part of this cascade may impair immune homeostasis and lead to severe clinical syndromes such as SLE. For instance, over-expression of complement C3 has been associated with promoted gastric cancer progression via activating JAK2/STAT3 signaling84 (Fig. 4).

Besides the complement system, other mechanisms also exist for debris clearance. For instance, marginal zone macrophages (MZMs) are crucial for clearing apoptotic cells and maintaining immune tolerance, dysfunction of which can lead to defected clearance of apoptotic cells, activated autoreactive T cells and expanded DN T cells.63

Diagnosis of SLE

Disease onset

SLE is highly heterogeneous with variable distinct clinical manifestations, and the disease severity varies from mild to moderate and to severe. For instance, skin inflammation might be restricted to malar rash in one individual but involve upper extremity and trunk as well in another.

The diagnosis of SLE is challenging as no consensus has been made on the diagnostic criteria that needs to be of both a high specificity and a high sensitivity.85 Currently, SLE is diagnosed by both clinical manifestations and laboratory examinations, where SLE manifestations can be defined by the presence of both subjective and objective findings, as well as laboratory examinations. Subjective observations include, e.g., headaches, chest pains, and arthralgias. Objective documentations include, e.g., electrocardiographic or echocardiographic confirmation of cardiac comorbidities. Lab tests include, e.g., autoantibody detection, functional test and imaging.8

The 1997-version ACR classification criterion has been canonically used for SLE diagnosis,86,87 with the classification indexes used being malar rash, discoid rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, non-erosive arthritis, pleuritis or pericarditis, renal disorder, neurological disorder, hematological syndrome, immunological evidence, and positive ANA. In the clinical practice, malar rash refers to erythema over the malar eminences that tends to spare the nasolabial folds; discoid rash is defined as erythematous raised patches with adherent keratotic scaling and follicular plugging; photosensitivity is documented as skin rash on sunlight exposure; oral ulcers is considered as oral or nasopharyngeal ulceration that is typically painless; non-erosive arthritis is defined as tenderness, swelling or effusion in peripheral joints; pleuritis or pericarditis refers to rubbing or evidence of pleural/pericardial effusion; renal disorder is considered if persistent proteinuria of >0.5 g/day occurred or cellular casts were present in urine including red blood cells or hemoglobin; neurological disorder primarily refers to seizures or psychosis; hematological disorder refers to hemolytic anemia with reticulocytosis, leukocytopaenia, lymphocytopaenia, or thrombocytopaenia; immunological evidence refers to the presence of anti-deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) autoantibody, anti-Sm autoantibody, or aPL autoantibodies; and positive ANA is defined as abnormal presence of ANA.8 These 11 indexes were updated in the 2019 EULAR/ACR classification criterion, with ‘fever’, ‘autoimmune hemolysis’, ‘non-scarring alopecia’, ‘low complement levels of C3 and/or C4’ being included, and ‘malar rash’ and ‘photosensitivity’ being removed. In addition, positive ANA was considered as an entry criterion for SLE characterization and a weighted system was used to assess the clinical and immunological manifestations of SLE in the 2019 EULAR/ACR classification criterion.88,89 Though specificities of these two ACR versions remain similar (i.e., 93%), the sensitivity of the 2019-version improved from 83% to 96% as compared with the 1997-version88 (Table 1).

The ACR criteria have been considered to be more feasible for classifying advanced SLE patients. This is because that the 1997-version requires the presence of no less than four items and the 2019-version requires even more indexes, as well as the fact that the symptoms accrue as the disease progresses.87,88,90

It is worth noting that the ACR criteria include the most prevalent manifestations but not all. For instance, the mucocutaneous manifestations included in the ACR criteria focus on discoid lupus and oral ulcers that do not cover other skin symptoms such as subacute cutaneous lupus, psoriasiform, and other forms of chronic cutaneous lupus; clinical syndromes from the neurological system is poorly represented in both the 1997 and 2019 versions of the ACR criteria that lack other important manifestations such as organic brain syndrome and cerebrovascular accident.91 Other SLE classification criteria also exist such as the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criterion that overcomes issues faced by the ACR criterion such as the lack of cutaneous and neuropsychiatric manifestations92 (Table 1). However, the specificity of the SLICC criterion drops from 93% to 84% despite its comparable sensitivity (i.e., 97%) with the 2019-version ACR criteria (i.e., 96%) due to the large spectrum of SLE manifestations it includes.87,92 Also, the SLICC classification criteria did not make substantial improvement in diagnosing patients with early disease onset as compared with the ACR criterion. Thus, unless more clever criteria with both increased sensitivity and specificity could be developed, the 2019-version ACR criterion may remain prevalent for SLE diagnosis. However, to enable accurate diagnosis of SLE with only a few indexes is challenging due to the extreme heterogeneous nature of this disease regarding its diversified clinical manifestations. One possibility would be to use molecular markers that requires in-depth understandings on SLE pathogenesis and identification of the leading signaling axis or panel of molecules marking the initiation and/or progression of SLE. Specifically, stratifying the pathogenic process of SLE into vital stages and identifying markers characterizing each phase may clearly mark the disease cause and activity of an individual on diagnosis. This may not only aid in the therapeutic design for precision medicine despite the heterogeneity nature of this disease, but also enable early diagnosis as markers are grouped by the stages following the line of disease initiation and progression.

Disease activity

Assessment of SLE activity conveys significant clinical values as it is a prognostic factor associated with mortality.93 However, accurate SLE activity measure is challenging due to the multifaceted clinical manifestations SLE possess and its extreme variation features over time.

Multiple indexes have been developed to assess the activity of SLE from multiple dimensions. The Systemic Lupus Activity Measure (SLAM) is a scale developed to assess the disease activity of SLE, which comprises items across 11 organ systems but does not require immunological test results and can be scored based solely on the physician’s clinical examination, making it applicable in areas where laboratory testing is limited. SLAM has a relatively satisfying high sensitivity and is currently widely used around the world.94 The SLEDAI95 together with its updated versions85,91,96 have been used to describe the overall burden of SLE. The Adjusted Mean SLEDAI-2000 (AMS) has been developed to measure the disease activity over time.97 However, SLEDAI and it updated versions have limitations in detecting clinically meaningful changes in the disease activity, as only complete remission but not partial improvement of the disease status can be captured using SLEDAI. Thus, SLE disease activity score (SLE-DAS) has been established accordingly to overcome such obstacles, which has displayed a desirable sensitivity for assessing alterations in disease activity.98 The British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) criteria and revisions99,100,101 are organ-specific indices assessing the partial improvement of SLE activity that can be used alone or as part of a composite index such as the BILAG-based Composite Lupus Assessment (BICLA).102 BICLA is integrated from BILAG, SLEDAI and Physician Global Assessment (PGA),103,104 which can comprehensively evaluate the benefits of an individual patient from a particular therapeutic towards an efficient utilization of the medical resources,105 and thus has been adopted by several clinical trials.106,107,108,109,110 Similarly, the SLEDAI-2000 Responder Index-50111 and composite indices such as the SLE Responder Index (SRI)112 are also available for assessing partial SLE improvement. The SLICC ACR Damage Index (SDI) has been developed to measure the accumulated organ damage ever since the disease onset,113 which has been shown to be a reliable114 independent outcome measure115 as well as a predictive index on future damage accrual and mortality.116 In addition, lupus low disease activity (LLDAS) has been used to describe prolonged disease remission or a serologically active (i.e., high anti-dsDNA antibody or low levels of complements) but clinically quiescent period among SLE patients.117 Therapeutically, patients during the LLDAS phase do not need specific treatment but require close surveillance118,119 (Table 1).

Disease comorbidities

As a direct result of SLE or a consequence of SLE medications such as glucocorticoids, SLE patients are at a high risk of developing several comorbidities. Thus, surveillance using measurements of each type of comorbidity should be adopted to prevent SLE patients from developing these diseases, which is crucial to their early identification and the prevention/intervention of these SLE-associated disorders among these patients.

Primary SLE comorbidities include cancers such as hematological malignancies, cardiovascular disorders such as atherosclerosis, bone diseases such as osteonecrosis, and neuropsychiatric symptoms such as cognitive dysfunction. In particular, SLE is associated with an increased risk of developing cancers, especially breast cancers, cervical cancers, hematological cancers, and lung cancers,120 with cancer screening being recommended for SLE carriers by the EULAR.9 SLE has been considered as a risk factor for atherosclerosis and been incorporated into the American Heart Association guidelines for cerebrovascular disease prevention among women.10 In addition, coronary artery disease was documented in 6-11% SLE patients, and subclinical carotid plaque was reported in 30-50% SLE carriers.121 SLE patients are at a high risk of developing osteonecrosis and osteopenia. Specifically, the incidences of osteoporosis and osteopenia occur in 1.4-68% and 25-74% SLE patients, respectively.122 Besides, SLE-related factors such as disease activity and medication use have been reported to be risky for developing low bone mineral density.122 Cognitive impairment occurs in up to 88% neuropsychiatric SLE123 that requires early diagnosis and appropriate interventions to prevent its long-term damage accumulation. Thus, there is an urgent need of standardized metrics for identifying cognitive impairment that, however, is lacking.124

Risk factors of SLE

Risk factors of SLE can be classified into intrinsic and extrinsic levels, with intrinsic factors being further grouped into those occurring at the genetic, epigenetic and hormonal levels, and extrinsic factors classifiable into environmental factors, habits, physiological factors and phycological factors. Before going into details of each type of SLE risk factors, it is worth to note that factors predisposing the risk of developing SLE is multifactorial that can not be explained solely by information from any of these layers, and risk factors from multiple levels can synergize to predispose the onset and severity of SLE. As examples, increased risks of developing SLE have been observed when genetic risk factors interact with smoking,125 and when the risk allele of the gene encoding chymotrypsin-like elastase family A member 1 (CTYP24A1) is coupled with insufficient vitamin D supply.126

While we focus more on intrinsic factors in this section and go into details of those at the genetic, epigenetic and hormonal levels to gain insights for intrinsic SLE predisposition, we emphasize extrinsic factors in the following section to identify preventive approaches for practical advice.

Genetic factors predisposing SLE

SLE is an autoimmune disease with a strong genetic disposition. Approximately 5-12% of people having one of his/her first-degree relatives carrying SLE will develop this disease in their lifetime.127 A series of landmark familial linkage studies and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in SLE have greatly advanced our understanding regarding the genetic basis of SLE.128,129,130 Currently, more than 100 SLE susceptibility loci have been consecutively identified (mostly from the European and Asian populations), which can explain up to 30% of SLE inheritability.131,132,133,134

Being a multigenic disease, several weighted genetic risk scores (GRS) have been established to assess the cumulative genetic susceptibility of an individual to SLE,125 with a higher GRS being associated with an earlier SLE onset and a higher disease activity.135 Male SLE patients, in general, have higher GRS than female carriers, implicating that the genetic factors play more dominant roles among males than females in predisposing SLE susceptibility.136

Genetic factors predisposing the incidence of SLE include both high-risk rare mutations and high-frequency polymorphisms (SNPs) that aggregate to collectively enhance the susceptibility of an individual to SLE. Of note, though each conveying a small effect on SLE risk by itself, low-frequency SNPs, once aggregated in a sufficient amount, may deliver substantial impact on SLE susceptibility.137 Genetic alleles so far identified are largely distributed in genes participating in IFN-relayed signal transduction, genes encoding components of the MHC region and altering the threshold for activating T/B lymphocytes, and genes encoding elements of the complement system such as C2, C4, C1q that impair the clearance of cellular debris.129,137,138,139 Genetic factors predisposing SLE susceptibility can be classified into three categories according to the molecular mechanisms they may participate in, i.e., stimulating the immune system, skewing immune regulatory signals, and impairing the debris clearance machinery.

Genetic factors associated with stimulated immune response

A large number of SLE-associated SNPs have been mapped to genes encoding proteins regulating or in response to type I IFNs such as genetic variants of IFN regulatory factor (IRF) 5 and IRF7.140 These SLE-associated genes are known as the ‘IFN signature’ actively participating in the innate immune response, and SLE patients possessing high levels of IFNα are inclined to manifest more severe disease syndromes.141 Mechanically, type I IFNs are produced in response to foreign material invasion for promoted maturation of DCs and production of proinflammatory cytokines, leading to, e.g., stimulated Th1 polarization and B cell activation. IRF5, being one member of the IFN signature with critical roles in regulating type I IFN-responsive genes, conveys a modest contribution to SLE risk (with the odds ratio being 1.5) and is considered to be the most strongly SLE-associated gene outside of MHC.142 As one example of SNPs of this kind, rs12537284 was identified through GWAS followed by meta-analysis and candidate gene investigations.143 STAT4 has recognized as a susceptibility gene of SLE that carries an additive value with IRF5 for increased risk of developing SLE.144 Accordingly, SNP risk variants rs3821236, rs3024866, rs7574865, being associated with high levels of STAT4 expression, conferred increased sensitivity to IFNα signaling in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of SLE patients and displayed earlier disease onset and more severe disease syndromes.145 Besides IRF5, SNPs associated with genes encoding other type I IFNs such as rs4963128 of IRF7146 and rs116440334 of IRF8147 have also been implicated in IFN pathways. Several other genes have also been identified capable of influencing IFNα signaling and the innate immune response. These include, e.g., IRAK1 (encoding IL1 receptor-associated kinase 1) that can be used to explain the female-predominance feature of SLE,148 and OPN (encoding osteopontin) that is associated with early SLE onset.149

In addition, SNPs residing in the genetic elements of microRNA (miRNA) critical for relaying IFN signals have been characterized.150 For instance, rs57095329, located in the promoter region of miRNA-146a, has been found to be highly associated with SLE susceptibility.150 Specifically, individuals carrying the risky G allele exhibited significantly reduced level of miRNA-146a than those carrying the protective C allele; and this may be attributed to the altered binding affinity of the transcription factor (TF) ETS proto-oncogene 1 (Ets-1) to the promoter region of miRNA-146a as a result of this genetic polymorphism.150

Genetic factors associated with immune signal relay

Another important portfolio of genetic risk factors predisposing SLE development are located in genes associated with the MHC especially human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DRB1 in the MHC class II region.151 HLA molecules play vital roles in auto-antibody production, as risk residues associated with the production of characteristic auto-antibodies (i.e., DRB1 residues 11, 13, 30) being located in the peptide-binding groove of HLA-DRB1.152 Furthermore, HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQB1 form the most significant haplotype, and seven residues (i.e., HLA-DRB1 residues 13, 11, 37, HLA-DQB1 residue 37, HLA-DPB1 residue 35, HLA-A residue 70, and HLA-B residue 9) collectively increase the explainable heritability of SLE due to HLA to 2.6%.152 Many other genes with essential roles in relaying signals downstream of activated T and B cell surface antigen receptors in the adaptive immune response and auto-antibody production have also been linked to SLE susceptibility.153,154 For instance, risky alleles of SNPs rs2230926 (TNFAIP3 that encodes TNFα induced protein 3),155 rs2476601 (PTPN22 that encodes protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 22),156,157 rs7829816 (LYN that encodes lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase),158 rs10513487 (BANK that encodes B cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats),153 rs7812879 (BLK that encodes B-cell receptor-associated protein kinase),159 rs340630 (AFF1 that encodes AF4/FMR2 family member 1),160 rs4810485 (CD40),161 rs3433034 (CSK that encodes C-terminal Src kinase),162 rs17849502 (NCF2 that encodes neutrophil cytosolic factor 2),163 rs1057233 (PU.1 that encodes purine rich box-1)164 have been reported to alter T and/or B cell activation threshold in the adaptive immune response for enhanced chance of developing SLE.

Genetic factors associated with debris clearance ability

As the classical pathway activating complement signaling may help remove apoptotic and damaged cells as well as ICs for reduced risk of developing autoimmunity to nuclear components,165 low copy numbers of C4 and C1q or deficiency of these genes are typically associated with increased SLE incidence. It has been estimated that the chance of developing SLE among individuals harboring congenital genetic deficiencies of C4 increased up to 90%.127 Several genetic mutations associated with the complement genes have been documented. For example, the C4A-null allele was associated with a doubled SLE susceptibility than either HLA-B8 or HLA-DR3,166 where HLA-B8 and HLA-DR3 alleles were known to predispose the risk of SLE via influencing early stages of adaptive immune activation.167 C1qA gene deficient mice have a greater chance of accumulating apoptotic bodies in the kidney and developing auto-antibodies to nuclear antigens.168 Also, C1q was shown protective against SLE via directing the immune stimulatory complexes to monocytes rather than DCs that secrete the pro-inflammatory cytokine IFNα,169 and through modulating CD8+ T cell mitochondrial metabolism for reduced immune response to self-antigens.170 In addition, multiple high-frequency low-risk genetic polymorphisms residing in 1q36 have been linked to genes encoding components of the complement system and been considered responsible for debris clearance.171,172,173

Epigenetic factors predisposing SLE

Epigenetic factors predisposing SLE include, primarily, miRNA, DNA methylation, and histone modification.

miRNA

miRNAs can act similarly as the TFs or interplay with TFs to cooperatively regulate the expression of target genes.174 Numerous studies have demonstrated the biological and clinical relevance of miRNAs in SLE. For instance, 42 differentially expressed miRNAs were identified from the PBMCs of SLE patients, among which 7 miRNAs (i.e., miRNA-10a, miRNA-130b, miRNA-134, miRNA-146a, miRNA-31, miRNA-95, miRNA-99a) were more than 6 folds lower in the diseased group as compared with the control.175 4 miRNAs (i.e., miRNA-371-5p, miRNA-423-5p, miRNA-638, miRNA-663) and 1 miRNA (i.e., miRNA-1224-3p) were found to be up- and down-ward regulated, respectively, in LN cells from a study investigating the miRNA profiles of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-infected B cells and frozen PMBCs from LN patients and unafflicted controls of different racial groups (i.e., American of African and European origins).176 While being up-regulated in this study, miRNA-423 and miRNA-663 were reported to be down-regulated in another study examining the miRNA profiles of kidney biopsy specimen, where 66 miRNAs were identified differentially expressed in LN cells.177 Focusing on T and B lymphocytes, it was reported that 3 miRNAs (i.e., miRNA-21, miRNA-25, miRNA-106b) were up-regulated in both T and B cells of SLE patients, 8 miRNAs (i.e., let-7a, let-7d, let-7g, miRNA-148a, miRNA-148b, miRNA-196a, miRNA-296, miRNA-324-3p) and 4 miRNAs (i.e., miRNA-15a, miRNA-16, miRNA-150, miRNA-155) showed altered expression in solely T and B cells of SLE patients, respectively, from a study analyzing the expression of 365 miRNAs in PBMCs from 34 SLE patients and 20 healthy individuals.178 Another group reported 11 miRNAs differentially expressed in CD4+ T cells from SLE patients, out of which 6 (i.e., miRNA-1246, miRNA-126, miRNA-1308, miRNA-574-5p, miRNA-638, miRNA-7) were up-regulated and 5 (i.e., miRNA-142-3p, miRNA-142-59, miRNA-155, miRNA-197, miRNA-31) were down-regulated.179 Although numerous miRNAs have been found dysregulated in human SLE patients or pre-clinical animal models, quite few miRNAs and their altered profilings were overlapping across studies, some of which even showed inconsistent patterns. This can be, at least, partially explained by the diversified manifestations and activities of SLE, as well as its heterogeneity regarding, e.g., ethical race and medication history. This makes miRNAs showing conserved alteration profiles among SLE patients highly valuable from the perspectives of both diagnosis and therapeutics.

miRNA-155: promoting SLE

Multiple lines of evidence have indicated that miRNA-155 is activated in response to the stimulation of TLR ligands,180,181 and up-regulated miRNA-155 is associated with activated TLR signaling. Multiple targets of miRNA-155 have been shown with critical roles during TLR signaling. For instance, suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS1), being a target of miRNA-155, participated in IFN-mediated antiviral response and thus attenuated viral propagation in macrophages.182 Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase D (INPP5D), another target of miRNA-155, negatively regulated TLR4 signaling in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation.183 Myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MyD88), being targeted by miRNA-155, acted as a vital adapter molecule in TLR signaling.184 TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1)-binding protein 2 (TAB2) is a direct target of miRNA-155 that activated TLR-mediated nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in LPS-activated DCs185 and plasmacytoid DCs.186 Besides, miRNA-155 played an essential role in dictating the antigen-presenting activity of DCs by suppressing the expression of PU.1 and cellular oncogene fos (c-Fos), two TFs with critical functionalities in regulating DC maturation,187 and defect DCs were associated with attenuated immune response.188,189

miRNA-155 also modulates the cytokine microenvironment by altering the distribution profiles between Th1 and Th2 cells. Specifically, altered Th1 function, skewed Th2 differentiation, and defective B-cell class switching were observed in mice carrying miRNA-155 deficiency as a result of abnormal secretion of cytokines such as TNFα, IL4 and IL10, and IFNγ.190,191 In addition, miRNA-155 affects cytokine homeostasis by changing the distribution between Th17 and Treg cells. For instance, miRNA-155 was negatively involved in Treg cell-mediated tolerance, as miRNA-155 depletion resulted in enhanced Treg-mediated immune suppression;192 and miRNA-155 knockout mice exhibited mass loss of Th17 cells coupled with marked reduction of inflammatory Th17 cytokines.193

miRNA-146a: suppressing SLE

On the opposite to miRNA-155, miRNA-146a level was negatively associated with the risk of SLE,194 substantially down-regulated in SLE patients, and adversely correlated with SLE activity.195,196

miRNA-146a functions as a strong negative regulator of TLR signaling by repressing TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) and IRAK1.197 miRNA-146a expression was inversely correlated with TNFα production, rendering cells tolerant and cross-tolerant to TLR stimulus.198,199 In line with these, miRNA-146a was found capable of regulating the production of type I IFNs (i.e., IFNα, IFN-β).175 Specifically, in SLE patients lack of miRNA-146a expression, aberrant accumulation of the targeted proteins of miRNA-146a (such as STAT1, IRF5, TRAF6, and IRAK1) led to altered activation of the IFN pathway;175 and exogenously introducing miRNA-146a into PBMCs from SLE patients dramatically alleviated the overtly activated type I IFN signaling.175 The latter can be evidenced by the approximately 75% reduction on the transcriptional levels of 3 IFN-inducible genes, i.e., IFN-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 (IFIT3), myxovirus resistance 1 (MX1), and 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1).175

Similar to miRNA-155, miRNA-146a regulates the cytokine microenvironment by affecting both the Th1/Th2 and Th17/Treg balances. Specifically, miRNA-146a was highly expressed in Treg cells in response to T cell receptor (TCR) activation, leading to impaired IFNγ-dependent Th1 activity and IL2 secretion, the process of which involved STAT1.200,201

Other miRNAs

miRNAs modulating immune response

Numerous evidence has supported the notion that miRNAs are essential players in TLR signaling for stimulating immune response. For example, miRNA-124 suppressed macrophage activation by repressing the expression of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/EBPα),202 miRNA-126 reduced the expression of PU.1 and thus TLR activation in allergic asthma.203 It is noteworthy that the same miRNAs may not act uniformly under distinct cellular contexts or pathologic conditions. For instance, let-7i, capable of negatively regulating TLR4 expression, was down-regulated in human cholangiocytes204 but up-regulated in DCs in response to LPS stimulation.205

miRNAs play critical roles in the regulation of T cell development. For example, miRNA-184 restricted the activation of CD4+ T cells during the early adaptive immune response and thus limited the production of IL2 by targeting nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 (NFAT1);206 miRNA-181c showed a similar function, the ectopic expression of which suppressed IL2 expression and thus reduced the proliferation of activated CD4+ T cells;207 furthermore, IL2 induced the expression of miRNA-182, leading to inhibited activity of Forkhead box O1(FOXO1) and T cell clonal expansion.208 miRNAs also actively participate in B cell development. For instance, miRNA-150 dramatically impaired B cell expansion via suppressing the critical TF required for B cell differentiation, i.e., c-Myb;209 miRNA-181a promoted B cell differentiation in mouse bone marrow when ectopically expressed in B cell progenitors210 besides regulating TCR signaling in immature T cells.211 It has been documented that transplanting bone marrow cells over-expressing miRNA-181a to lethally irradiated mice promoted the growth of CD19+ B cells and reduced the amount of CD8+ T cells.210

miRNAs modulating cytokine microenvironment

Besides targeting TLR signaling pathways and regulating immune cell development, multiple lines of evidence have unambiguously supported the essential roles of miRNAs played in modulating cytokine homeostasis. It has been well documented that altered secretion profiles of cytokines such as IL2, IL6, IL10, and regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) play crucial roles in SLE development, and miRNAs participate in SLE development through modulating the production of these primary cytokines. For example, the level of RANTES was documented to be abnormally over-represented in the blood sera of SLE patients, whereas that of IL2 was reported to be significantly lower in lupus T cells. Under-expressed miRNA-31 contributed to the decreased IL2 expression in PBMCs or lupus T cells.175,179 miRNA-142-3p was highly induced in DCs in response to LPS stimulation, leading to suppressed IL6 production.212 Up-regulated miRNA-21 expression has been positively associated with SLE activity, reduced level of which in SLE CD4+ T cells led to decreased IL10 production.178 Through characterizing miRNAs lowly expressed among SLE patients, miRNA-125a was found capable of reducing T cell-mediated RANTES production via targeting its TF, i.e., Kruppel-like factor 13 (KLF13), and exogenously introducing miRNA-125a into the T cells of SLE patients resulted in significantly alleviated up-regulation on RANTES expression and SLE severity.213

DNA methylation

DNA methylation level has been considered to be lower in SLE patients or lupus animal models.214,215 Specifically, DNA extracted from the CD4+ T cells of SLE patients was hypomethylated,215 and adoptive transfer of T cells pre-treated with DNA methylation inhibitors induced SLE symptoms in unirradiated syngeneic mice.216,217 A clinical study involving 1521 Chinese and European SLE patients, along with healthy controls and patients with other autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS), revealed that SLE patients are characteristic of hypomethylation at two CpG sites within the promoter region of IFI44L, SLE patients with renal involvement displayed even lower methylation levels at these sites, and the methylation levels increased among SLE carriers during remission.218 These suggested that the methylation level of the promoter region of IFI44L may serve as the blood biomarker for SLE prognosis and diagnosis.218 In Feb 2024, the world’s first innovative IFI44L gene methylation detection product was approved by National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) of China for SLE prognosis prior to the onset of vital organ damage.219 This may be attributable to the inhibited inheritance of DNA methylation profiles during mitosis in response to perturbations such as aging and diet220,221,222 that involves the participation of multiple miRNAs such as miRNA-126, miRNA-148a and miRNA-21.179,223

DNA methylation patterns are regulated by methyltransferases, including DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1), DNMT3A, DNMT3B, and DNMT3L.224,225 While, DNMT1 maintains DNA methylation profiles, DNMT3A and DNMT3B introduce de novo DNA methylation, and DNMT3L assists the functionalities of DNMT3A and DNMT3B.226,227 It has been reported that miRNAs such as miRNA-126179 and miRNA-148a223 regulated the levels of DMNT1 in the T cells of SLE patients. Specifically, miRNA-148a and miRNA-21 were robustly up-regulated in CD4+ T cells from SLE patients lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice, giving rise to DNA hypomethylation via suppressing DNMT1 expression;223 and miRNA-126 inhibited DNA methylation in CD4+ T cells of SLE patients by binding to the 3’ untranslated region (3’ UTR) of DNMT1.179 In addition, defective ERK pathway in T cells negatively affected DNMT1 expression and enhanced the development of anti-dsDNA antibodies in transgenic mice,228 suggesting the involvement of suppressed ERK signaling in priming DNA hypomethylation among SLE carriers.

Histone modification

Histone 3 (H3) and Histone 4 (H4) hypoacetylation and site-specific histone methylation alterations were found in the CD4+ T cells from SLE patients and MRL-lpr/lpr mice splenocytes.229,230 It has been reported that the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) can restore skewed expression of IL10, IFNγ and CD154 in lupus T cells,231 and treating MRL-lpr/lpr mice with histone deacetylase inhibitors TSA and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) reduced the section of IL6, IL10, IL12, and IFNγ.232,233 These findings implicated that histone modification variation contribute to the modulation of cytokine distribution in SLE pathogenesis.

Hormonal factors predisposing SLE

Female hormones such as estrogen and prolactin contribute to the activation of the immune system and thus predispose the prevalence of SLE, leading to the extreme female predominance among SLE carriers. Specifically, estrogen functions by skewing the cytokine microenvironment to favor Th2, prolactin acts via activating the immune response. Progesterone, on the other hand, represents a protective factor of SLE by damping the immune activating signals.

Estrogen

Estrogens have been reported to potentiate Th2-mediated diseases including SLE by inhibiting the production of Th1 pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL12, TNFα and IFN({rm{gamma }}), and stimulating the secretion of Th2 anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL4, IL10, and TGFβ.68

Estrogens include estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), and estriol (E3), with E2 being the primary biologically active estrogen. Estrogen receptors (ERs), both nuclear and membrane bound, have been identified in various types of cells involved in the innate and adaptive immune responses.234 While the nuclear ERs include ERα and ERβ, the membrane-bound ER is the G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER).235 ERs contain three functional domains, i.e., trans-activation domain, DNA-binding domain, and ligand-binding domain.236 During nuclear ER signaling, ERα and ERβ typically act in an opposite fashion in response to E2 treatment and regulate almost distinct sets of genes, with only 38 out of 228 genes being regulated by both ERα and ERβ.237 Nuclear ER signaling can be long-term and manifest genomic information via transcriptionally regulating a plethora of factors including, e.g., cytokines such as IFNs and signaling pathways such as JAK/STAT signaling.234,238,239 Different from nuclear ER signaling, GPER-mediated signaling is rapid and nongenomic. Specifically, the signal transduction cascade is initiated via intracellular calcium and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) induction, and leads to activated phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K)/ AKT and mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) signaling.235

Estrogen contributes to the polarization of the cytokine environment to the Th2 state, where a shift of the balance between Th1 and Th2 subsets to Th2 dominance is characteristic of SLE. Specifically, low doses of estrogen promote Th1 responses for increased cellular immunity, and high doses of estrogen elevate Th2 responses for stronger humoral immune responses.240,241 This effect of estrogens is achieved via altering the Th cytokine profile from a Th1-dominant state (IL12, IFNγ, TNFα) to a Th2-dominant profile (IL4, IL6, IL10, TGFβ).68 For instance, E2 as well as E1 and E3 have been shown to stimulate TNFα secretion at low concentrations and inhibit it at high concentrations,242 the effect of which on IL10 production was shown to be the opposite.243

Prolactin

Prolactin, with increased levels detected in the serum of SLE patients, functions as both a hormone and a cytokine. Prolactin has been shown capable of stimulating almost all primary players in the innate and adaptive immune responses such as T cells, B cells, DCs, natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and hematopoietic stem cells according to a collection of in vitro, in vivo and clinical evidences. Though prolactin disruption is not essential for the normal development and functionality of the immune system,244 prolactin can synergize with IL2 in B cell activation and differentiation.245 In addition, the prolactin receptor is expressed on human immune cells including T and B lymphocytes and monocytes,246 suggestive of its promotive roles in SLE development.

Progesterone

Pregnancy-associated changes in progesterone signaling has been considered important for innate immune surveillance and tolerogenic response, rendering progesteron a protective factor of SLE. Specifically, progesterone reduces the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL1β and IL12, leading to attenuated activities of primary players involved in both the innate and adaptive immune responses such as macrophages, DCs, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.239

Extrinsic factors predisposing SLE

The contribution of extrinsic risk factors to SLE susceptibility increases with age, as a greater contribution of known SLE genetic risk alleles (especially residing in non-HLA genes) were found among children who developed SLE than adult SLE patients.247,248

Extrinsic trigger of SLE can be primarily classified into three categories based on their effects on SLE pathogenesis, i.e., events introducing immune activators, perturbing cytokine microenvironment homeostasis, and inducing inflammation.8

Events introducing immunoreactants

EBV infection can increase the amount of EBV nucleic acids in the blood of SLE patients,249 which activates the innate immunity and B cell differentiation by expressing type I IFNs and stimulating the production of autoantibodies specific for EBV-encoded proteins.250,251 It is worth noting that EBV infection predisposes to SLE development but not vice versa, as the serum anti-EBV capsid antigen IgG levels of SLE patients were significantly higher than healthy individuals that did not apply to anti-EBV nuclear antigen.252 The mRNA/DNA vaccines may also induce SLE. It has been reported that the application of mRNA or DNA vaccines against the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has been shown capable of causing new or relapsed onset of SLE.253,254,255,256 A boost in spike protein-specific CD4+ Th1 and CD8+ T cell responses were detected after the use of AZD1222 (i.e., a DNA COVID-19 vaccine),257 the mechanism of which could be attributed to activated TLRs followed by induced type I IFNs-mediated signaling. Additionally, agonists of TLR7 and/or TLR9 have been oftenly supplemented as the adjuvants in mRNA/DNA COVID-19 vaccines for enhanced immunity,258,259 further aggregating the development of SLE.

UV light irradiation may activate the autoimmune response via generating nucleic acid fragments, attributing to its breakage role on DNA strands.46 A clinical study examined the sensitivities of 100 SLE patients to UV radiation, where 93% patients showed abnormal reaction to UV and visible light including, e.g., superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and deposition of immunoreactants such as IgG and C3.260

Medications with pro-inflammatory roles may also induce SLE that can be manifested as vasodilation and hypotension. For instance, hydralazine (a vasodilator) and procainamide (an anti-arrhythmic agent) can trigger SLE via forming neutrophil extracellular trap (NET)261,262 that can function as the auto-antigens due to DNA, histones and neutrophil proteins it contains.263 Excessive secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFNα (used for treating Hepatitis B/C) aggravates SLE.264,265,266

Habits such as tobacco smoking is a known risk factor for SLE in a dose-dependent manner as it is a stimulus capable of inducing nonspecific inflammation and, thus, autoimmune responses among SLE carriers.267

Events skewing cytokine microenvironment

Some medications may induce SLE, though the symptoms may be milder than idiopathic SLE. The mechanisms-of-action may be attributed to their roles in skewing the cytokine microenvironment. For instance, carbamazepine, an anticonvulsive agent traditionally used for treating epileps and neuropathic pain, can increase IL5 secretion that marks Th2 production, attributing to the terminal metabolite acridine it produced.268 Sulfasalazine, used for treating rheumatoid arthritis, can skew the cytokine microenvironment to Th2-dominant state by suppressing IL12 production in macrophages.269 Another example refers to antibodies against TNFα that have been used as immunosuppressors in the treatment of autoimmune or inflammatory diseases. Infliximab, an anti-TNFα antibody, induced the production of anti-dsDNA antibody and SLE among more rheumatoid arthritis patients.270,271 Similarly, hydralazine, procainamide and other DNA methyltransferase inhibitors such as 5-azacytidine may turn CD4+ T cells autoreactive to spontaneously lysed syngeneic macrophages and produce more IL4/6 and IFNγ to induce SLE.216,220 The combinatorial use of minocycline (a semi-synthetic tetracycline-class broad-spectrum antiboitic) with bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in treating autoimmune encephalomyelitis, though having achieved desirable therapeutic effects in an autoimmune encephalomyelitic mice model, may increase the risk of developing SLE syndromes as a result of suppressed production of IFNγ and TNFα as well as increased generation of IL4 and IL10.272 Paradoxically, minocycline decreased C-C motif chemokine ligand 22 (CCL22) production from macrophage type 2 for reduced Th2 recruitment to the lesion,273 implicating the importance of cytokine microenvironment homeostasis in preventing autoimmune syndromes that is dictated, at least partially, by the type and cytokine profile of the syndrome as well as the medication strategy being applied.

Preventive strategies for SLE management

SLE could be initiated and accelerated by complicated dynamic interplays between intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Specifically, once individuals possessing SLE genetic, epigenetic or hormonal risk factors are chronically exposed to extrinsic risk factors, accelerated disease onset and deterioration may occur. As intrinsic risk factors including those at the genetic, epigenetic, hormonal levels are difficult to control, we focus on preventive approaches against the extrinsic risk factors in this section.

Extrinsic factors can be environmental situations such as virus infection, UV light irradiation, heavy metal exposure, air pollution and silica, habitual factors such as unhealthy diet, cigarette smoking, lack of physical exercises and sleep deprivation, physiological conditions such as comorbidities, obesity and pregnancy, and psychological factors such as trauma and stress.274,275,276 Current conceptions on a healthy lifestyle with a lower risk of developing SLE overall include, e.g., a healthy eating habit (i.e., top 40% of the Alternative Healthy Eating Index), no smoking, moderate alcohol consumption (i.e., no less than 5 gm per day), regular exercise (performing at least 19 metabolic equivalent hours of exercise per week), and fitness (i.e., body mass index below 25 kg/m2).277 Each of these preventive recommendations has a 19% additive value in reducing the chance of developing SLE especially among anti-dsDNA antibody positive patients; and the cumulative risk of having SLE can be reduced to half of those with the poorest behavior for individuals keeping the best adherence to the healthy lifestyle. This implicates that extrinsic factors may act synergistically to influence the risk of SLE, and SLE may be prevented by, e.g., altering the lifestyle among other extrinsic factors.

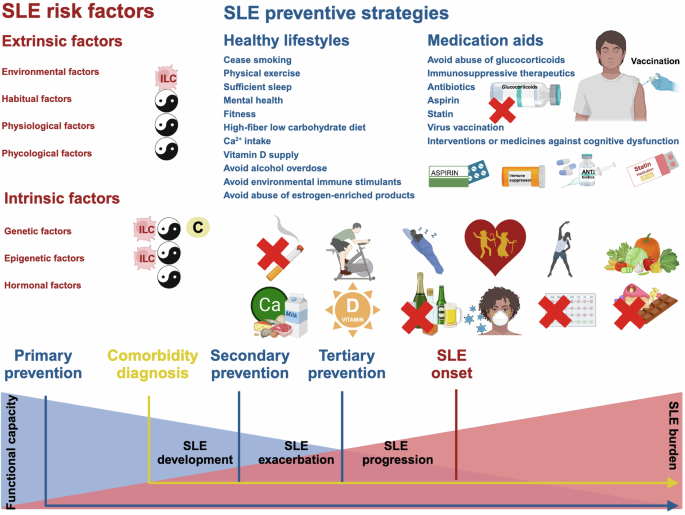

Preventive strategies can be classified into three stages, i.e., primary prevention, secondary prevention, tertiary prevention, which should be adopted as early as possible to prevent the development, exacerbation and progression of SLE, respectively. This especially holds true for individuals who have already been prognosed at a high risk of developing SLE or diagnosed with SLE.

Following the rationals of mechanisms-of-action, preventive strategies can be classified into approaches against events introducing immune stimulants, and skewing the cytokine microenvironment (Fig. 5).

Risk factors and preventive strategies against SLE development, exacerbation, progression. Risk factors predisposing SLE can be classified into intrinsic and extrinsic factors (in red). Intrinsic factors can occur at genetic, epigenetic and hormonal levels. Extrinsic factors can be environmental, habitual, physiological and phycological. Among these extrinsic factors, SLE comorbidities from the category of physiological factors include cancers, cardiovascular diseases, bone diseases and neuropsychiatric diseases. As intrinsic SLE predisposing factors are difficult to control, preventive strategies against each extrinsic risk factors are listed (in blue). By summarizing preventive strategies against SLE and its comorbidities, 11 recommendations on the lifestyles (i.e., cease smoking, physical exercise, sufficient sleep, mental health, fitness, High-fiber low carbohydrate diet, Ca2+ intake, vitamin D supply, avoid alcohol overdose, avoid environmental immune stimulants, avoid abuse of estrogen-enriched products) and 7 advises on medication aids (avoid abuse of glucocorticoids, immunosuppressive therapeutics, antibiotics, aspirin, statin, virus vaccination, interventions of medicines against cognitive dysfunction) are given. SLE preventive strategies can be classified into three stages, i.e., primary prevention against SLE development, secondary prevention against SLE exacerbation, tertiary prevention against SLE progression. The prevention of SLE comorbidities should start at the time of diagnosis. Applying preventive strategies as early as possible during the disease course can help to avoid organ damage, which is a major trigger of systematic functional decline. Primary prevention recommendations are emphasized using cartoons

Prevention of SLE

Preventive strategies recommended below are categorized by the pathogenic stages leading to SLE. These approaches are suitable to individuals diagnosed with high risks of developing SLE for prevented disease onset, and to SLE patients for alleviated disease symptom or delayed disease progression.

It is worth to highlight that intrinsic and extrinsic factors especially biomarkers at the genetic and epigenetic levels as aforementioned can aid in SLE prevention and early intervention, since they could help identify individuals with the high risk of developing SLE that require early adoption of prevention strategies.

Also deserves emphasizing is that there is current no consensus on strategies for SLE prevention given the complexity and heterogeneity of the etiology of this disease. Besides, the full spectrum of preventive strategies against SLE is not completely uncovered, personalized prognosis and prevention modality design are not yet available. Thus, approaches beneficial to one individual may not be optimal or even effective to another.

Prevention against events introducing immune stimulants

As an important type of extrinsic factors, environmental situations with SLE-predisposing roles such as EBV infection, exposure to UV light, heavy metals such as mercury,278 agricultural pesticides,278,279,280 air pollution, crystalline silica dust,281,282,283,284 and other respiratory particulates285,286 largely act via exposing individuals with immune stimulants. These factors function primarily by stimulating cellular necrosis and secreting intracellular antigens for up-regulated IFN levels and promoted inflammation. Take EBV infection as an example, it functions by releasing EBV-encoded small RNA from infected cells that induces type I IFN signaling (in particular TLR3-mediated signals),287 with a substantially higher seroprevalence of anti-viral capsid antigens IgG and antibodies against early antigens being observed among SLE patients as compared with non-diseased controls according to a meta-analysis involving 25 case-control studies.252 Additionally, UVB radiation, another important trigger of SLE, led to a significant rise in type I IFN signaling and prolonged activation of T cells both in lupus-prone mice and among SLE patients.288,289,290 A randomized, vehicle-controlled, double-blind clinical study including 25 CLE patients revealed the photoprotective effects of broad-spectrum sunscreen.291 There also exists clinical evidence supporting the benefits of using sunscreen for preventing the onset or worsening of SLE.292 Yet it is worth noting that the association of UV radiation with SLE risk is convolved with its positive roles in vitamin D3 synthesis293 that may, to some extent, reduces SLE risk.294 Therefore, keeping away from immune stimulants such as virus infection, overt UV light exposure and any environmental pollutant is highly advised among individuals genetically predisposed with SLE.

Receiving vaccination to elevate the thresholds of responding to environmental stimuli may represent another useful strategy. Yet, the efficacy of vaccination in reducing SLE risk remains to be elucidated.295 This is because that vaccines may contain elements such as molecular mimicry, auto-antibodies and adjuvants that can potentially trigger autoimmune responses towards accelerated SLE. Evidences supporting this rational include a series of reports on the new-onset of autoimmune diseases including autoimmune hepatitis disease,296 autoimmune thrombotic events,297 rheumatoid arthritis,298 immunoglobulin A vasculitis,299 Guillain-Barré Syndrome and,300 importantly, SLE,255,301 after getting vaccinated against COVID-19. Also, a clinical case on the transition of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) to SLE after COVID-19 vaccination has been identified.302 However, these reports are largely from case reports or cross-sectional studies representing temporal associations and are not from vaccinations against EBV. On the other hand, therapeutic EBV vaccines have been considered promising in treating cancers with acceptable toxicity.303 Take together, establishing vaccines against EBV or any other immune stimulants for SLE prevention may be worthwhile to try but requires intensive investigations and clinical monitoring on the possible adverse effects accompanied besides the efficacy.

Prevention against events skewing cytokine microenvironment

Many lifestyles and physiological conditions associated with SLE predisposition can increase levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to skewed cytokine microenvironment.

Cigarette smoking has been associated with increased risk of developing anti-dsDNA antibody positive SLE than non-smokers by several clinical investigations,267,304,305 linked to augmented autoreactive B cells by a clinical evidence based meta-analysis,267 and associated with induced pulmonary ANA in the lungs of exposed mice.306 In addition, a cross-sectional study containing 105 smokers revealed the positive association of cigarette smoking with cumulative chronic damage in SLE patients and its deleterious effects on lupus morbidity.307 This may be attributed to the toxic components of the cigarette that can damage DNA to form immunogenic DNA adducts for promoted production of anti-dsDNA antibody and pro-inflammatory cytokines.308,309 In particular, smoking can increase the expression of B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) that is a soluble ligand of the TNF cytokine family,306 TNFα and IL6.310 Among positive ANA women, elevated BLyS and lower IL10 (an anti-inflammatory cytokine) levels were identified among frequent smokers.311 Therefore, cease smoking is highly recommend especially for those with genetic preposition to SLE.