Breast cancer: pathogenesis and treatments

Introduction

Breast cancer remains a formidable adversary in the landscape of global health challenges, with its intricate pathogenesis and diverse clinical manifestations posing significant obstacles to effective treatment and prevention.1,2,3 As the global incidence of this disease continues to rise,4 it is imperative to unravel the multifaceted nature of breast cancer to develop effective therapeutic strategies.

Despite advancements in early detection and therapeutic strategies, the disease exhibits a complex etiology that necessitates a deeper understanding of its molecular underpinnings and risk factors. There are many factors affecting the tumorigenesis of breast cancer, and evidence illustrates the intricate interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors that contribute to that process.5,6,7 Understanding these factors can help in breast cancer prevention and early detection. In addition, the progression of tumor is influenced by various factors operating through distinct mechanisms (such as tumor stemness, intra-tumoral microbiota, and circadian rhythms), and a comprehensive investigation into these mechanisms is essential for identifying potential clinical therapeutic targets.8

With the continuous advancements in experimental techniques and sequencing technology, significant progress has been made in the detection and diagnosis of tumor. For example, the combination of liquid biopsy and high-throughput sequencing technology has opened new avenues for cancer diagnosis.9,10 Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing clinical oncology, with considerable potential to improve early tumor detection and risk assessment and to enable more accurate personalized treatment recommendations.11,12,13,14 The application of these emerging diagnostic methods in breast cancer will be discussed in this review. The traditional treatments for breast cancer include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, targeted therapy, and other related approaches.15 In recent years, the advent of precision medicine has set the stage for a new era in breast cancer treatment, with an emphasis on tailored therapies that target the specific molecular characteristics of individual tumors.16 Additionally, long-term management of patients with tumors, including breast cancer, is crucial as it directly impacts patients’ quality of life and survival time.17,18,19

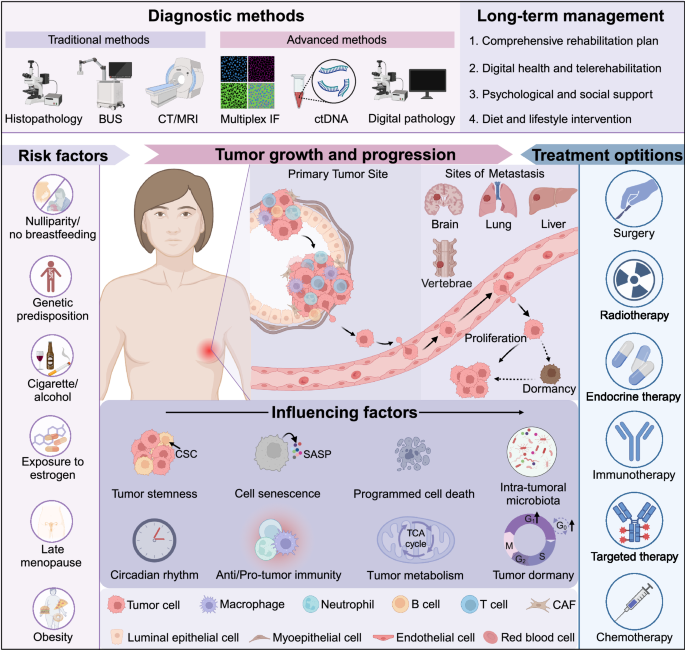

Tracking the latest research advancements is crucial for deepening our understanding of breast cancer and enhancing treatment outcomes for patients. This comprehensive review provides a synthesis of the latest current knowledge, focusing on recent breakthroughs and emerging trends in the pathogenesis, progression, diagnostics, treatment, and follow-up management of breast cancer (Fig. 1).

Comprehensive overview of breast cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent tumors in women, and its occurrence is associated with a multitude of factors, such as genetic mutations, late menopause, and obesity. The progression of breast cancer is shaped by numerous factors, encompassing both tumor cell characteristics and elements within the tumor microenvironment, whether cellular or non-cellular. In recent years, there have been significant advancements in diagnostic technologies for breast cancer. Alongside traditional imaging techniques and pathological diagnosis methods, liquid biopsy, and multiple immunofluorescence assays, digital pathology approaches are gradually being incorporated into clinical practice. Treatment options for breast cancer are diverse, and recent clinical studies emphasize the importance of individualized and precision treatments. Long-term follow-up management of breast cancer patients is also crucial, as it may impact both the therapeutic outcomes and enhancing patients’ quality of life. BUS B-scan ultrasonography, CT computed tomography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, IF immunofluorescence, ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, CSC cancer stem cell, SASP senescence-associated secretory phenotype, TCA cycle tricarboxylic acid cycle. The figure was created with Biorender.com

Epidemiology and risk factors of breast cancer

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease with distinct subtypes characterized by unique epidemiological patterns.20 Globally, breast cancer accounts for roughly one-third of all malignancies in women, with its mortality rate constituting about 15% of the total number of cases diagnosed.4,21 A complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors influences the global distribution of breast cancer. High-income countries typically exhibit higher incidence rates than low- and middle-income countries, although mortality rates are often lower due to better access to early detection and treatment.1 It is noteworthy that the absolute number of breast cancer cases is increasing in many developing countries due to population growth and the adoption of western lifestyles.22 Fortunately and predictably, the death rates will decline in the future with extending access to advanced prevention, early diagnosis, and medical intervention services for females.2

Breast carcinogenesis and risk factors

Didactically, breast carcinogenesis is a series of genetic and environmental events that drive the multistep process of transformation of normal cells via the steps of hyperplasia, premalignant change, and in situ carcinoma.23 Germline mutations and the subsequent second somatic mutation (also known as the “two-hit” model) caused by various environmental factors or exposure to high estrogenic factors lead to the accumulation of genomic changes.24 The clonal accumulation of cells leads histologically to ductal hyperplasia, initially without atypia. While in the promotion phase, the expansions of mutation clones form by stimulating the cellular proliferation of autocrine growth factors or recruiting inflammatory and stromal cells to produce these factors, evolving mechanisms to evade the immune system.25 These accumulative alterations from both genomic instabilities and external factors result in precursor lesions. Under the long-term action of these carcinogenic alterations, cells continue to adapt and select, and this change gradually increases and accumulates.26 DNA damage or mutations develop to a certain extent, which exceeds the limit of self-repair, contributing to in situ carcinoma, where the pathological cells are confined within the ducts but have not yet invaded the surrounding tissues.27 The pathological journey of breast cancer from in situ to invasive cancer is another complex process, starting with abnormally proliferating cells in the breast lobules. This transition is characterized by acquiring invasive and metastatic properties, facilitated by genetic alterations and interactions with the tumor microenvironment (Table 1).28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 The invasive phase is often marked by increased aggressiveness and a higher risk of distant spread, underscoring the importance of early detection and interventions.48 Hence, breast carcinogenesis is a multistep process involving the accumulation of genetic alterations and the influence of various risk factors.

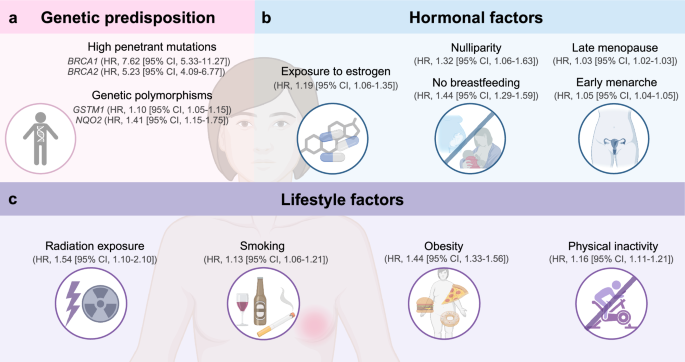

The leading risk factors involve a combination of genetic predisposition, hormonal factors, reproductive history, and lifestyle choices (Fig. 2).5

Risk factors for breast cancer. Hormonal factors such as long-term exposure to estrogen, nulliparity and no breastfeeding, late menopause, or early menarche increase the risk of breast cancer. Genetic predisposition is a serious health hazard. High penetrant mutations and genetic polymorphisms are the two parts. Patients with genetic mutations such as BRCA1/2 or patients whose first-degree relative has history of breast cancer are more susceptible to this malignancy. Low penetrant mutations, including GSTM1 and NQO2, are included in genetic polymorphisms of breast cancer susceptibility. Unhealthy lifestyle may also lead to breast cancer. Overdose exposure to radiation and/or heavy alcohol consumption, smoking, having diet high in fat or sugar, obesity, physical inactivity are the leading causes. HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval. The figure was created with Biorender.com

Genetic predisposition

Genetic predisposition is the first and the most noticeable part.49 An inherited susceptibility to breast cancer is based on an identified germline mutation in one allele of a moderate to high penetrance susceptibility gene (such as BRCA1/2, CHEK2, PALB2, and TP53). Inactivation of the second allele of tumor suppressor genes would be an early event in this oncogenic pathway.3,50 Protein-truncating variants in five genes (ATM, BRCA1/2, CHEK2, and PALB2) were associated with a risk of breast cancer.6,51 However, above moderate to high penetrance susceptibility gene mutations only account for ~5% of overall breast cancer cases3; attention should be paid to low penetrance susceptibility genetic variation. It mainly includes single-nucleotide polymorphism, insertion/deletion polymorphism, copy number variation, etc. Typical genes, such as CYP17, CYP19, GSTM1, and NQO2, are involved in estrogen synthesis.52,53,54 Although the effect of individual sites of these low penetrance genetic variants is weak, the superposition or synergistic effect of multiple sites plays a crucial role in the risk of breast cancer. Notably, the co-occurrence of genomic alterations like TP53mut–AURKAamp are deeper insights that reveal the underlying genomic changes in breast cancer.55

Hormonal factors

Hormonal factors like long-term exposure to estrogen56and reproductive history influenced by factors such as late menopause,57 early menarche for every year younger at menarche,58 nulliparity,59 and abortion60 exhibit a connection to an elevated vulnerability to breast cancer.61 Childbirth and breastfeeding have been shown to mitigate the predisposition to breast cancer, possibly due to hormonal changes and differentiation of breast tissue.62

Unhealthy lifestyles

Lifestyles cannot be neglected: exposure to radiation,63 obesity and physical inactivity,64 alcohol consumption,65 and smoking66 are modifiable risk factors that have been linked to an increased risk of breast cancer.67,68 Notably, we have an updated understanding of the risk factors for breast cancer. Circadian rhythm disorder can change the expression of clock genes, disrupt the normal cell cycle, and then directly promote the initiation of malignancy.69,70,71 Indirectly, the disorders probably inhibit melatonin secretion and accelerate the inflammatory response, thus facilitating oncogenesis.72 Although the mechanism remains unclear, regular physical activity is regarded as a protective factor of breast cancer incidence.73 Several hypotheses aim to explain why physical activity might prevent cancer by reducing the exposure to endogenous sex hormones, altering immune system responses, or insulin-like growth factor-1 levels.74

Although risk factors brought about by environmental changes may be an important cause of breast cancer, we cannot ignore the serious consequences of genetic changes interacting with them. Next, we will look at classic examples of gene-environment interactions and offer our views.

Gene-environment interaction studies

As described above, various factors, the dual interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures, defined here as radiation, chemicals, and additional external factors, have become a critical area of research on the lengthy issue of breast cancer origin.75 Both environmental and genetic factors are critical in a local cellular milieu where tumors initiate and determine the fate of cells.76 For the vast majority of diseases, it is apparent that combinations of synergistic or antagonistic factors of both gene and environment are crucial to the risk. Studies have demonstrated environmental factors, such as diet, tobacco intake, chemical exposures, and outdoor light at night, can influence gene expression and contribute to breast cancer risk.77 Tobacco smoking increases stop-gain mutations, which may lead to early termination of protein-coding and disrupt the formation of tumor suppressor factors, thereby elevating the susceptibility to breast cancer.78 On the flip side, insulin resistance single-nucleotide polymorphisms and lifestyles combined synergistically increased the risk of breast cancer in a gene-behavior, dose-dependent manner, suggesting lifestyle changes can prevent breast cancer in women who carry the risk genotype.79 So, it is not hard to imagine that an individual carrying a particular genetic variant may be at greater risk for breast carcinoma if a related pernicious environmental factor is present. Although the potential gene-environment interactions that have been identified are of small to moderate magnitude (probably limited by the number of populations included),80,81 we should regard hereditary variants and environmental factors as additive risks in the prediction of breast cancer susceptibility. Studies are focusing on how these exposures interact with genetic factors to affect cancer development, such as multiple metabolic reprogramming and increased susceptibility to breast cancer.7,82,83,84,85 Currently available research models for studying gene-environment interactions including genome-wide association study, genome-wide interaction search, Bayes model averaging approach, binary regression model, logistic regression model, etc. Knowledge of gene-environment interaction is essential for risk prediction and the identification of specific high-risk populations to inform public health strategies for targeted prevention.

AI and big data-assisted analysis of individual risks

As the incorporation of AI in disease management covers multiple fields, including screening, diagnosis, relapse forecasting, survival duration prediction, and treatment efficacy measurement, it offers new insights into risk prediction and personalized prevention.86,87,88 Algorithms and models brought by interdisciplinary research, such as deep-learning models, spiking neural networks, deep belief networks, convolutional neural networks, etc.,89,90 can analyze vast amounts of data in a shorter time to identify patterns, predict individual risk, and give recommendations more accurately than traditional assays.

For the screening and diagnosis of breast cancer, the convolutional neural network is mainly used for image classification of cancer. It carries out a series of nonlinear transformations on structured data (such as the original pixels of the image) and automatically learns related features of the image, which does not require manual sorting like traditional machine learning models. With the help of the AI, radiologists decrease their false positive rates by 37.3% but maintaining the same level of sensitivity.91 AI support systems including Transpara and MammoScreen have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for clinical practice.92 Specifically, AI diffraction analysis is a novel tool for recognizing cells directly from diffraction patterns and classifying breast cancer types using deep-learning-based analysis of sample aspirates for breast cancer diagnosis of fine needle aspirates.93 Other AI-based pathological diagnostic tools for breast cancer include slide-DNA, slide-seq, DeepGrade based on digital whole-slide histopathology images contribute to improving the both efficacy and accuracy.94,95,96 As for therapy and drug development, deep-learning algorithms play vital roles in drug screenings.97 The AI clinical decision-support systems Watson for Oncology provides individualized evidence-based treatment advice, especially at centers where expert Breast Cancer Resources are limited.98

From the above, AI and Big Data-assisted analysis have been shown to give its high inputs in the automated diagnosis as well as treatment of breast cancer, even in managing epidemics, machine learning assists in achieving elementary epidemiological breast cancer prediction by country to exam the emerging risk factors and estimate corresponding incidence rate for a future interval of years.99,100 In the near future, these AI-driven strategies will help tailor individual risk profiles and provide targeted prevention.

In short, breast cancer’s multifaceted nature arises from a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, leading to various molecular subtypes with distinct pathophysiologies. Understanding these subtypes is crucial for personalized treatment and prognosis.

Pathophysiology and molecular subtypes of breast cancer

Pathophysiology and molecular subtypes of breast cancer are crucial for understanding the disease’s development, progression, and response to treatment. This knowledge aids in the development of targeted therapies, personalized medicine, and improved patient outcomes. Recognizing subtypes allows for tailored treatment plans, enhancing survival rates and quality of life for those affected by breast cancer.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of breast cancer

The clinical presentation can vary from a painless palpable breast mass to more advanced symptoms such as skin changes, nipple discharge, or local pain, with or without palpable axillary mass, nipple discharge and inversion, and breast skin thickening.15 Patients that are presented as only axillary lymph node metastases (known as occult breast cancer), which account for about 0.3–1.0%,101 are easy-to-miss diagnosis and need to be paid more attention. Pathologically, breast cancer is classified into breast invasive carcinoma (70–75%) and lobular carcinoma (12–15%) as suggested by the World Health Organization classification.102 There are also eighteen other uncommon subtypes, with a proportion of 0.5–5%.102 The pathological descriptions should also include the histological type, histological grade, immunohistochemistry assessment of hormone receptor (HR) status [estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status], human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) expression or HER2 gene amplification, and Ki67. For further prognostic evaluation and clinical decision-making, breast cancer can be classified into three subgroups based on immunohistochemical staining results for ER, PR, and HER2: HR-positive/HER2−negative (HR+/HER2−, ~70%), HER2−positive (HER2+, ~15–20%), and triple-negative breast cancer [TNBC, HR-negative (HR-), HER2−, ~15%].15,103 Of additional concern, the prevalence of the HR+/HER2− subtype (~50–60%) in China is lower than that in white women, which probably lies in the younger age of the affected population in China, while HER2− subtype accounts for 25% and TNBC accounts for ~15–25%.104 In clinical practice, immunohistochemical results are often used to define the four subtypes, namely luminal A, luminal B, HER2−enriched, and TNBC. Luminal A is characterized by high ER and PR and overexpression of the HER2 receptor and Ki67, which indicates slower cell growth, better prognosis, and better response to hormone therapy.While luminal B cancers are also HR-positive but can be either HER2+ or HER2−. They have higher levels of Ki67, indicating faster cell growth and may be treated with hormone therapy and chemotherapy. HER2−enriched ones have high levels of the HER2, which are often more aggressive but can benefit from HER2−targeted therapies. TNBCs do not express ER, PR, or HER2, with a higher risk of recurrence and poorer prognosis. Each subtype has unique clinical outcomes, phenotypes, and therapeutic sensitivities, which guide treatment decisions and influence prognosis.

The precise mechanisms of breast cancer progression are not fully understood. As mentioned above, the etiology of breast cancer involves a complex array of genetic and environmental factors that contribute to the malignant transformation of breast cells. The tumor microenvironment, characterized by interactions between tumor cells, stromal cells, and immune cells, further modulates carcinogenesis. Understanding these mechanisms is vital for developing preventive strategies and targeted therapies.

Extensive research has characterized the molecular features of breast cancer and outlined its progression. At the cellular level, both the clonal evolution model and the cancer stem cell model are widely accepted, with the possibility of tumor stem cells evolving clonally, adding complexity to the situation.105 Morphologically, a spectrum of changes and genetic alterations occurs as normal glandular tissue transitions to cancer. Molecularly, numerous gene mutations, hormonal receptor changes, and immune interactions occur throughout the tumorigenesis and progression of breast cancer. The identification of breast cancer susceptibility genes BRCA1/2, whose proteins are involved in DNA repair through homologous recombination,106,107 has shed light on some mechanisms behind sporadic and hereditary breast cancers. The primary pathogenic mechanism contains genetic alternations, hormonal homeostasis changes, and immune interference, which are demonstrated as follows.

Genetic alterations

Genetic mutations are the basis for carcinogenesis. Carrying the heterozygous mutation of BRCA1/2, transformation to complete malignancy of cells occurs after a serious external secondary hit, further resulting in genome instability and cellular disorders. The genetic instability ulteriorly leads to genetic alterations in cells, such as somatic mutations of PIK3CA and TP53, which are non-inherited.108 Additionally, chromosomal instability, which is a hallmark of cancer,109 is responsible for driving somatic copy number variations and intratumor heterogeneity within subclones during cancer progressions.110 In the process of tumor evolution, DNA copy number loss, transcript repression, epigenetic silencing, and whole-genome doubling are different ways for potential malignant cells to acquire immune evasion and fueling adaptive abilities in response to various pressure.110,111 Through a series of complex disruptions of the genome, cells acquire the accumulation of deleterious alterations irreversibly to survive in purifying selection (removing deleterious genetic variations) of human germline evolution, further obtaining fitness, attenuating tumor cell attrition and evolving to malignancies.112

Changes in hormonal homeostasis

Hormonal exposure (including menopausal hormone therapy, overdose estrogen intake from food, and endocrine instability caused by various reasons) accounts for the main contributing factors for sporadic breast malignancies. Specifically, estrogen binding to the nuclear ER (encoded by ESR1) is an inducer of breast cancer. Imbalances between estrogen and progesterone can promote cell proliferation and potentially lead to the accumulation of DNA damage. At this juncture, excess estrogen promotes the expansion of these malignant cells and triggers an increase in the supportive stroma, which in turn facilitates the progression of cancer.113 Upon ligand engagement, the ER modulates the transcription of genes by binding to estrogen response elements in their promoter areas, thereby controlling gene expression.114 Additionally, ER can engage directly with other proteins, including those involved in growth signaling pathways, which, in turn, amplifies the transcription of genes that are pivotal for cellular expansion and resistance to apoptosis.115 In a word, disturbances in estrogen homeostasis in the breast tissue may promote breast cancer progression and metastasis.

Immune interference

Breast cancer cells develop within a complex microenvironment that includes various benign cell types and extracellular matrix. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are the predominant cell type present; however, the breast cancer microenvironment is also populated by lymphocytes, macrophages, myeloid lineage cells, etc., which predominantly play roles in immune reactions.116,117 In the early stages of tumor development, the immune microenvironment mainly suppresses tumor proliferation through the cytokine environment produced by activated CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Whereas, once the tumor turns aggressive, tumor cells express immune checkpoint modulators [such as cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1)] to suppress the immune response. The composition of microenvironmental cells, including CAFs and the content of cytokines, is influenced by the “invasion” of breast cancer cells, thereby promoting tumor progression.118

Breast cancer exhibits unique mechanisms of immune evasion that contribute to its progression and resistance to immunotherapy. Breast cancer can evolve over time, leading to increased genomic complexity and heterogeneity, which may impose selective pressures and result in differential responses to therapies.119 Detailly, breast cancer cells mimic the anti-inflammatory mechanism of central nervous system to evade antitumor immunity, which is dependent on the immunological synapse.120 Carrying lower clonal heterogeneity and neoantigen loads, TNBC cells achieve immune escape via Lgals2-CSF1-CSF1R axis,121 which is also a specific mechanism in breast cancer immune escape.

The interplay between breast cancer cells and host antitumor immunity determines co-existing mechanisms of immune escape within the same patient, highlighting the need for combinatory immunotherapies and biomarker development.

Molecular subtypes and variability in tumorigenesis across different subtypes of breast cancer

Understanding the molecular subtypes and variability in tumorigenesis across different breast cancer subtypes allows for tailored treatments, improved patient outcomes, and the discovery of new therapeutic targets. This understanding is critical for advancing clinical trials and translating research into clinical practice, ultimately revolutionizing breast cancer management.

Variability in tumorigenesis across different subtypes

As mentioned in the previous part, the immunogenicity of breast cancer varies among multiple molecular variants, with TNBC and HER2+ tumors being more immunogenic, while luminal A and luminal B subtypes are less immunogenic.119 Since breast cancer is a highly heterogeneous disorder, it is not surprising that the subtype changes metastasis or under the pressure of therapies.122 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can probably change ER and PR expression and status. Changes in ER, PR, and HER2 receptors are more evident in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and trastuzumab than those without. It is worth noting that retesting of the hormone and HER2 receptors should be considered in certain situations to optimize adjuvant systemic therapy.123

Molecular subtypes of breast cancer

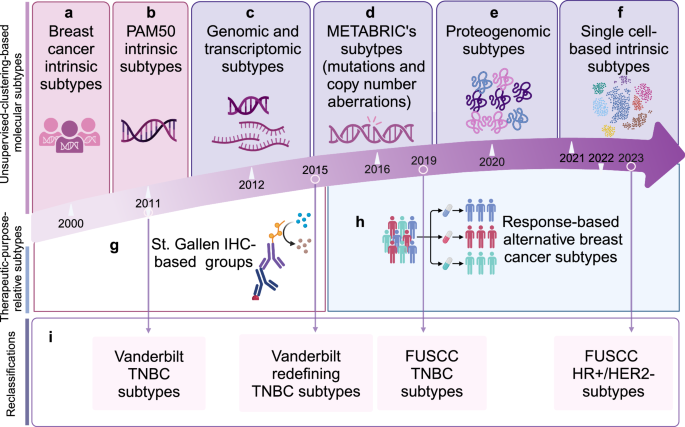

The past few decades have witnessed the promotion and popularization of the concept of classification-based treatment (Fig. 3). Roughly, the subtypes of breast cancer can be divided into two groups, namely unsupervised-clustering-based molecular subtypes and subtypes with therapeutic intent. With the development of sequencing techniques, the unsupervised-clustering-based molecular subtypes have been iteratively updated substantially. In 2000, the concept of molecular typing of breast cancer was born.124 According to the similarities and differences of gene expression profiles, tumors can be divided into luminal A/B, HER2−enriched, basal-like, and normal-like subtypes. In 2009, PAM50 assay redefined those subtypes using the microarrays of fifty genes.125 In 2012, integrating the genome and transcriptome from representative patients provided a novel molecular stratification of the breast cancer population.126 This unsupervised analysis revealed novel subgroups with distinct clinical outcomes, which reproduced in the validation cohort. Deletions in PPP2R2A, MTAP and MAP2K4 were identified by delineating expression outlier genes driven in cis by CNAs. In 2021, the complex cellular ecosystems were stratified into nine clusters according to a single-cell method of intrinsic subtype,127 which broadened our horizons of our limited understanding of cellular composition and organization in breast cancer. In this classification, the stromal-immune niches were spatially organized in tumors, offering insights into antitumor immune regulation. After the overall classification, reclassification after the general subtype also emerged in an endless stream. Studies have shown that TNBC is a group of diseases with molecular genetic heterogeneity. Lehmann et al. divided TNBC into six subtypes from the molecular classification: basal-like 1/2, immune modulative, mesenchymal, mesenchymal stem cell-like, and luminal androgen receptor subtypes,128and subsequently Burstein et al. refined the six TNBC subtypes into four subgroups.129 Based on the cohort from Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, molecular classifications of TNBC and HR+/HER2− breast cancer were further developed.130,131,132

General timeline for redefining breast cancer molecular subtypes. The subtypes of breast cancer can be divided into two groups, namely unsupervised-clustering-based molecular subtypes and therapeutic-purpose-relative subtypes. a Perou et al. firstly proposed the concept of molecular typing of breast cancer in 2000 by using DNA microarrays representing >8000 genes. b Parker et al. constructed PAM50 subtypes in 2009, which was a simplified version of the “intrinsic” subtypes. c In 2012, Christina et al. offered an integration of the genome and transcriptome from representative patients, which provided a novel molecular stratification of the breast cancer population. d Bernard et al. identified ten subtypes of breast cancer from the landscape of mutations, driver copy number aberrations. e Unsupervised proteogenomics identified four molecular subtypes underscore the potential of proteomics for clinical investigation in 2020. f In 2021, another update called single-cell method of intrinsic subtype stratified the complex cellular ecosystems into nine clusters. g IHC-based subtype was the first therapeutic-purpose-relative subtype raised in 2011. h An alternative subtype was constructed in 2022 according to various regimens redefined and supported the usage of response-based subtypes to guide future treatment prioritization. i Reclassifications of the specific subtypes include Vanderbilt TNBC subtypes in 2011, Vanderbilt redefining TNBC subtypes in 2015, FUSCC TNBC subtypes in 2019 and FUSCC HR+/HER2− subtypes in 2023. IHC immunohistochemistry, TNBC triple-negative breast cancer, FUSCC Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, HR hormone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor-2. The figure was created with Biorender.com

As for the therapeutic-purpose-relative subtype, St. Gallen International Breast Cancer Conference adopted an immunohistochemical-based subtype including luminal A-like, luminal B-like, HER2 overexpression (non-luminal), and basal-like subtypes.133 Subsequent studies showed significant differences in breast cancer prognosis among different molecular subtypes.134 In 2022, an alternative subtype was constructed according to various regimens redefined and supported the usage of response-based subtypes to guide future treatment prioritization.135 More than 11 subtyping schemas were explored and this redefinition identified treatment-subtype pairs maximizing the pathologic complete response (pCR) rate over the population. Understanding these subtypes is critical for the development of targeted therapies and personalized medicine approaches.

Taken together, the clinical and pathological characteristics, pathogenic mechanisms, and molecular subtypes of breast cancer collectively contribute to its complexity and diversity. Continued research in these areas is essential for enhancing the precision of diagnoses, optimizing therapeutic approaches, and boosting patients’ survival.

Mechanisms of breast cancer progression: frontier research

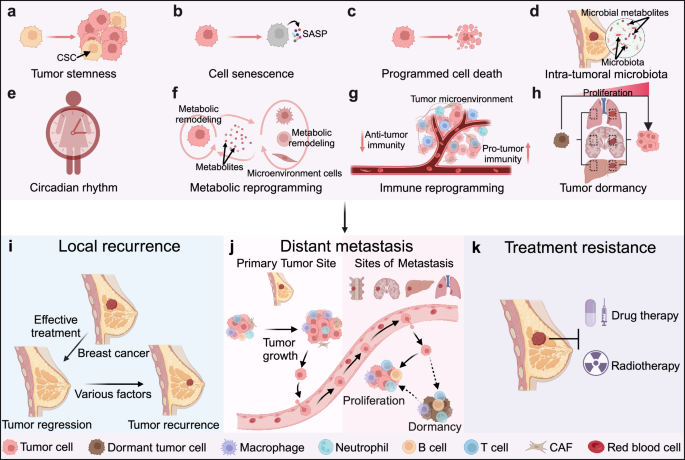

For all tumors, including breast cancer, tumor progression results in local relapse, metastasis, and treatment resistance, and represents great clinical challenges that need to be addressed.8,136,137 With the continuous advancements of experimental techniques and sequencing technology (such as single-cell sequencing and spatial omics), significant strides have been made in comprehending the underlying mechanisms driving tumor progression. Belows are highlighted some key factors contributing to the progression of breast cancer (Fig. 4).

Diverse factors regulating the progression of breast cancer. Many factors contribute to the progression of breast cancer, resulting in local recurrence (i), metastasis (j), and treatment resistance (k) of breast cancer. These factors include tumor stemness (a), cellular senescence (b), novel types of programmed cell death (c), intra-tumoral microbiota (d), circadian rhythm (e), metabolic reprogramming (f), immune reprogramming (g), as well as tumor dormancy (h). CSC cancer stem cell, SASP senescence-associated secretory phenotype. The figure was created with Biorender.com

Tumor stemness

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) constitute a minor fraction of the tumor population, characterized by their capacity for self-renewal and differentiation.138,139 A plethora of compelling evidence substantiates that CSCs play a pivotal role in driving tumor initiation, conferring resistance to treatment, facilitating recurrence, and promoting metastasis.140,141 Although CSCs represent a functional cellular state, it has been demonstrated that their identification can be facilitated by utilizing specific cell markers such as CD133, CD44, EPCAM, and ALDH1, among others.142

In solid tumors, the first identification and isolation of CSCs was conducted in breast cancer,143 which also plays a significant role in its progression. Kita-Kyushu lung cancer antigen-1 (KK-LC-1), identified as a novel marker for TNBC CSCs, inhibits Hippo signaling by binding to FAT1. This facilitates the nuclear translocation of YAP1, subsequently triggering the transcription of ALDH1A1. Pharmacological inhibition of downstream signal transduction mediated by KK-LC-1 significantly impairs TNBC tumor growth.144 EMSY is also a newly discovered biomarker of TNBC CSCs, It competitively binds to the Jmjc domain, which is critical for KDM5B enzyme activity, thereby reshaping methionine metabolism in CSCs. This metabolic reprogramming enhances CSCs self-renewal and tumorigenesis through an H3K4 methylation-dependent mechanism.145 F-box protein FBXL2, known as a negative regulator of stemness by targeting the transcription factor E47 for polyubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation in breast cancer, is significantly down-regulated in paclitaxel-resistant TNBC cells; however, its activator can be utilized to reduce the stemness of TNBC cells and enhance treatment sensitivity to paclitaxel.146

An interesting phenomenon is that breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs)—secreted DKK1 can effectively suppress the proportion of the stem cell population both in vivo and in vitro. This reduces tumor initiation ability while simultaneously increasing the expression of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), which protects tumor cells from lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis that promote tumor metastasis.147 Nuclear mRNA export is a crucial step in eukaryotic gene expression. Prostate cancer-associated transcript 6 (PCAT6), a long non-coding RNA, enhances nuclear mRNA export related to BCSCs, thereby increasing stemness and resistance to doxorubicin in breast cancer.148 The utilization of radiotherapy is considered a crucial therapeutic modality for treating tumors. However, the emergence of radiation resistance frequently poses significant clinical challenges.149 Upregulation of THOC2 and THOC5 protein expression can promote the THOC-mediated spliced mRNA efflux, leading to increased synthesis of NANOG and SOX2 proteins; This process can strengthen the stem-like properties of TNBC cells and contribute to their increased resistance to radiotherapy.150

The stemness of tumor cells is regulated by internal signals and influenced by the tumor microenvironment. LSECtin, a transmembrane protein expressed primarily on macrophages, can enhance breast cancer stemness and promote the growth of breast cancer in a contact-dependent manner.151 Moreover, breast cancer cells can secrete CCL20 to stimulate the production of a significant amount of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CXCL2) by polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells. The binding of CXCL2 to the CXCR2 on the surface of tumor cells activates the CXCR2/NOTCH1/HEY1 signaling pathway, leading to increased tumor cell stemness and mediating resistance to docetaxel.152 In addition to immune cells, TNBC tumor cells also receive secretory signals from CAFs through the IL-8/CXCR1/2 axis to maintain their stemness state.153 The extracellular matrix (ECM), a non-cellular component of the tumor microenvironment, has a physical structure and chemical composition often associated with tumor progression.154 The relatively low mechanical stress (about 45 Pa) derived by the ECM can stimulate the stem cell signaling pathway via the cytoskeleton/AIRE axis by activating the integrin beta 1/3 receptor, while excessive mechanical stress (~450 Pa) induces quiescence in BCSCs dependent on DDR2/STAT1/P27 signaling, which may explain conflicting results observed in previous individual studies.155

Cellular senescence

Cellular senescence is a self-defense mechanism triggered by internal and external stimulation, playing a pivotal role in organismal development and post-injury repair.156 Cell cycle arrest, resistance to apoptosis, and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) are the primary hallmarks of cellular senescence.157 It should be noted that cellular senescence should not be conflated with the broader concept of aging, as the latter encompasses a more comprehensive range of phenomena beyond just cellular senescence.158 Cellular senescence is intricately involved in various physiological and pathological processes within the body,159 exhibiting a dualistic role in tumorigenesis by both promoting and suppressing cancer.160,161

In the oncogene-driven Neu and MMTV-PyMT mouse models, the overactivation of the RANK signaling pathway in normal mammary epithelium induces cellular senescence, thereby delaying the onset of breast cancer but promoting subsequent metastatic invasion.162 During breast cancer chemotherapy, specific tumor cells exhibit upregulation of SASP genes, accompanied by an augmented expression of immunosuppressive molecules PD-L1 and CD80 within these tumor cells. This phenomenon facilitates immune evasiveness, thereby facilitating the survival of tumor cells during chemotherapy.163

The concept of cellular senescence within tumors extends beyond the tumor cells themselves. CAFs are stromal cells within the tumor microenvironment that exhibit diverse biological characteristics, often demonstrating tumor-promoting activity.164 The extracellular matrix secreted by senescent CAFs, as identified through single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), is found to specifically limit the cytotoxicity of natural killer (NK) cells, thereby promoting tumor growth.165 In another study, a distinct senescence-like tetraspanin-8 (TSPAN8)+myofibroblastic CAF (myCAF) subgroup potentiates tumor stemness through SASP-associated factors IL-6 and IL-8, thereby promoting chemotherapy resistance in breast cancer.166 Within the tumor microenvironment, neutrophils exist in various functional states that promote or suppress cancer progression.167 The breast cancer cells can engulf exosomes secreted by senescent neutrophils, thereby enhancing their resistance to chemotherapy.168 Additionally, senescent neutrophils can accumulate at pre-metastatic sites for lung metastasis in breast cancer patients, forming neutrophil extracellular traps that effectively ensnare tumor cells and facilitate lung metastasis.169

Novel types of programmed cell death

Cell death is crucial for the development and maintenance of homeostasis in organisms and can be categorized into accidental cell death and regulated cell death (RCD), depending on its controlled nature.170 RCD, also referred to as programmed cell death (PCD), encompasses various forms, including apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, entotic cell death, netotic cell death, parthanatos, lysosome-dependent cell death, autophagy-dependent cell death, alkaliptosis, and oxeiptosis; all of which occur through distinct mechanisms and are associated with tumorigenesis and tumor progression.170,171,172

Ferroptosis is a natural antitumor mechanism; however, tumor cells possess a distinct advantage in evading ferroptosis. The occurrence of ferroptosis not only impacts tumor cells but also regulates the antitumor immune response.173 Among the four subtypes of TNBC,132 the luminal androgen receptor (LAR) subtype exhibits the highest ferroptosis activity. The utilization of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4, one of the core regulatory factors of ferroptosis174) inhibitors can effectively attenuate tumor proliferation and enhance antitumor immunity, while combining GPX4 inhibitors with immunotherapy can further impede tumor progression.175 Furthermore, in breast cancer, tumors exhibiting high levels of imaging tumor heterogeneity are associated with a poor prognosis. However, these tumors show increased activation of key pathways that promote and inhibit ferroptosis, suggesting that targeting drugs that promote ferroptosis could be an effective clinical target.176

Cuproptosis177 and disulfidoptosis178 have expanded the concept of PCD in recent years. Copper is an indispensable trace element in the human body, and the copper-dependent growth and proliferation of cells are related to various biological behaviors of tumors.179 However, excessive intracellular copper accumulation can induce mitochondrial proteotoxic stress and ultimately result in cellular apoptosis, known as cuproptosis, a process primarily regulated by ferredoxin 1.177 Targeting cuproptosis holds significant implications for tumor therapy.180 In preclinical models of breast cancer, some novel nanomedicines that target cuproptosis have demonstrated efficacy in inhibiting tumor growth and may hold potential for future clinical applications.181,182 The occurrence of disulfidptosis is primarily attributed to the elevated expression level of SLC7A11 in cells, which leads to excessive cystine uptake. The metabolism of cystine necessitates the consumption of NADPH. However, inadequate NADPH production in cells with restricted glucose intake significantly augments actin cytoskeletal disulfide bonds, causing disruption in the actin network and intracellular disulfide hyperplasia. Consequently, cell disulfide stress ensues, ultimately leading to cell death.178 Although limited research has been conducted on disulfidptosis in tumors, targeting disulfidptosis, such as through glucose transporter inhibitors, could present a novel therapeutic approach for SLC7A11 overexpressing tumors in the future.183,184 Both ferroptosis and disulfidptosis depend on intracellular redox homeostasis.173 Drugs that disrupt this homeostasis can promote the simultaneous occurrence of both processes, thereby inhibiting tumor progression.185 This indicates that these drugs may represent more effective clinical therapeutic targets, warranting further investigation into their potential applications.

Intra-tumoral microbiota

Although most normal tissues in the human body are commonly perceived as sterile, bacteria186 and fungi187,188,189 can be detected in tumor tissues, particularly in tumor cells and immune cells, using various technical methods. These microorganisms are not mere bystanders in the tumor microenvironment; instead, they can promote tumorigenesis and tumor progression.190,191,192,193,194,195

Bacteria within breast cancer cells have been observed in situ tumors.186 It has been observed that genera under Clostridiales are enriched in immunomodulatory subtype among TNBC patients, with high levels of its associated metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). TMAO induces pyroptosis of tumor cells by activating the endoplasmic reticulum stress kinase PERK, thus enhancing the antitumor immune effect of CD8+ T cells.196 When tumor cells metastasize to distant sites through the circulatory system, they are exposed to severe stress within the blood vessels, such as hemodynamic shear forces and attacks of the immune system.197 Remarkably, circulating tumor cells can carry bacteria, which promote cytoskeletal reorganization and enhance the tumor cells’ resistance to fluid shear stress in the bloodstream. This ultimately facilitates host cell survival and distant metastasis.198

The origin of microbes in breast cancer has remained an unresolved question. Fusobacterium nucleatum, a bacterium closely associated with colorectal cancer,192,199 can translocate to breast cancer tissues exhibiting high Gal-GalNAc expression through hematogenous spread, primarily via the interaction between Fap2 expressed by Fusobacterium nucleatum and Gal-GalNAc on the surface of breast cancer cells. The inoculation of Fusobacterium nucleatum hampers T-cell infiltration within the tumor, thereby facilitating tumor progression and metastasis.200

Circadian rhythm

Life activities follow a 24-hour cycle known as the circadian rhythm or biological clock, which is regulated by intricate signaling pathways within the body and influenced by external factors such as light and temperature.201,202 The circadian rhythm exerts an influence on the immune function203 and metabolic activities204 of the body, playing a pivotal role in upholding normal physiological functions. The disruption of this rhythm is closely linked to a range of diseases, such as neurodegenerative disorders,205 cardiovascular diseases,206 kidney diseases,207 and tumors.208,209,210,211,212

Disruptions to the normal circadian rhythm can increase the risk of breast cancer.213,214 Specifically, disturbances in the circadian rhythm not only enhance the malignant potential of breast cancer cells (including their ability for self-renewal, replication, metastasis, and invasion) but also impact chemokine/chemokine receptor signaling (the CXCL12-CXCR4 axis may be the primary signaling pathway) which contributes to the formation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment ultimately leading to tumor progression. The CXCR2 chemokine receptor inhibitor can correct the effects of long-term circadian rhythm disruption on the dissemination and metastasis of breast cancer cells.215 Furthermore, CTCs are pivotal in tumor dissemination through the bloodstream.216 The production of highly metastatic CTCs in breast cancer is significantly higher during sleep compared to the less metastatic CTCs produced during daytime activity, indicating the importance of considering time nodes in clinical sample collection and tumor treatment. Mechanistically, CTCs exhibit high expression of various circadian rhythm hormones receptors, and circadian hormones, such as melatonin, can influence the production of CTCs. Analysis of CTCs obtained from patients and mouse models during the resting phase using scRNA-seq reveals significant upregulation of mitotic genes, which may contribute to the enhanced metastatic potential of CTCs.69

Metabolic reprogramming

One hallmark of tumors is altered energy metabolism, with the most well-known example being the Warburg effect.217 Throughout the progression from precancerous lesions to localized tumors and from tumors in situ to metastatic tumors, the metabolic preferences of tumor cells continuously change in response to cellular states and environmental conditions, which are regulated by endogenous signals from tumor cells and signals from the tumor microenvironment.218 The alterations in tumor cells’ metabolic preferences are associated with tumor progression.219,220,221

MYC is a commonly occurring oncogene,222 yet the metabolic characteristics of tumors with high MYC expression are still worth exploring. In breast cancer, MYC regulates the elevated expression of vitamin transporter SLC5A6 in tumor cells, promoting intracellular transport of vitamin B5 and its conversion to coenzyme A. This enhances metabolic pathways such as the tricarboxylic acid cycle and fatty acid biosynthesis, ultimately supporting tumor growth.223 Dynamin-related protein 1 promotes fragmented mitochondrial puncta formation in latent brain metastatic cells, leading to a shift towards fatty acid oxidation (FAO) metabolism that maintains redox homeostasis and survival of tumor cells within the brain microenvironment.224 Analysis of scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics data from paired primary breast cancer tumors and lymph node metastatic tissues revealed that the process of lymph node metastasis in breast cancer involves a metabolic shift from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation and back to glycolysis, indicating a potential target for the treatment of tumor metastasis.225

The altered metabolic characteristics of brain metastatic cells in breast cancer not only affect tumor cells themselves but also impact antitumor immunity within the brain microenvironment. In HER2+ breast cancer, the metabolic characteristics of synchronous brain metastatic (S-BM) cells, metachronous brain metastatic (M-BM) cells, and latent (Lat) brain metastatic cells are distinct. S-BM cells exhibit increased glycolytic activity, resulting in elevated lactate production. This lactate, secreted into the tumor microenvironment, inhibits the function of NK cells, aiding tumor cells in evading immune surveillance. Inhibiting lactate metabolism in S-BM cells significantly impedes metastasis. M-BM and Lat cells demonstrate enhanced capabilities to utilize glutamine in response to oxidative stress due to the high expression of the anionic amino acid transporter (xCT), which enhances the survival capacity of tumor cells. Pharmacological inhibition of xCT can reduce residual disease and recurrence.226

Notably, the metabolic characteristics of non-tumor cells within the tumor microenvironment also undergo alterations to support tumor growth and metastasis.227,228,229,230 CAFs enhance their glycolytic activity, producing large amounts of lactate that breast cancer cells can absorb and utilize.231 Resident lung mesenchymal cells accumulate neutral lipids intracellularly during the pre-metastatic breast cancer lung metastasis phase. These lipids are transferred via vesicles to tumor cells and NK cells, promoting tumor cell proliferation while inhibiting NK cell function.232 During breast cancer progression, the stiffened fibrotic tumor microenvironment enhances the TGFβ autocrine pathway in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), activating their collagen biosynthesis program. This process consumes large amounts of arginine and increases ornithine secretion. Reduced arginine and elevated ornithine levels in the tumor microenvironment impair CD8+ T-cell function, ultimately leading to tumor progression.233

Immune reprogramming

A properly functioning immune system is crucial for killing and eliminating tumor cells.234,235,236,237 Unfortunately, tumor cells often “remodel” the tumor immune microenvironment through various mechanisms to achieve immune evasiveness,238 such as reducing tumor antigen presentation, decreasing the infiltration or function of tumor-inhibitory immune cells, and promoting the infiltration of immunosuppressive cells.239,240

The precise mechanisms by which tumor cells restrict immune cell infiltration into tumors remain incompletely understood. In PTEN-deficient breast cancer, the expression of PI3Kβ in tumor cells significantly hampers the infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells via the BMX/STAT3 signaling pathway, leading to the formation of an “immune desert” within tumors and facilitating tumor immune evasiveness.241 Another study indicates that the extracellular domain (ICD) of discoidin domain receptor 1 is released by tumor cells during tumor progression, causing changes in the alignment of collagen fibers in the extracellular matrix (ECM). This alteration forms a barrier to immune cell infiltration, protecting tumor cells from immune cell-mediated killing.242

The function of immune cells infiltrating tumor cells can also be suppressed, preventing them from exerting their typical effects. In immune checkpoint inhibitor-resistant HER2+ breast cancer, tumor cells upregulate the expression of N-acetyltransferase 8-like to produce high N-acetylaspartate (NAA) levels. After being absorbed by NK cells and CD8+ T cells, NAA can inhibit the formation of immunological synapses in these cells, leading to immune evasiveness.120 Additionally, FGF21 secreted by breast cancer cells can alter cholesterol metabolism in CD8+ T cells, causing excessive cholesterol biosynthesis and inducing CD8+ T-cell exhaustion.243 The TAMs are immune cells that exhibit immunosuppressive functions, and reducing TAMs infiltration can inhibit tumor growth and improve survival rate.244 Using large-scale in vivo CRISPR screening technology, researchers have identified the E3 ligase Cop1 within breast cancer cells as an essential regulator of macrophage chemokine secretion. The expression of Cop1 promotes the secretion of macrophage-associated chemokines by tumor cells, which enhances macrophage infiltration within the tumor, particularly M2 macrophages. Inhibiting Cop1 can enhance antitumor immunity and improves the response to anti-PD-1 therapy.245

Before lung metastasis in breast cancer, there was a discernible alteration in the local pulmonary microenvironment, primarily characterized by a decrease in the quantity and impaired functionality of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and NK cells, potentially mediated by the primary tumor.246 In comparison to the primary site, breast cancer metastases (including lymph nodes, lung, liver, and brain) also undergo substantial immune reprogramming with an augmented presence of immunosuppressive cells and compromised antitumor immunity.246,247,248

The functions of B cells are diverse and play a crucial and complex role in tumor progression.249 In patients with TNBC who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, researchers utilized scRNA-seq to identify that chemotherapy can induce the accumulation of ICOSL+ B cells. Specifically, complement signals triggered by chemotherapy-induced immunogenic cell death of tumor cells promote the transition of other B cells into ICOSL + B cells. These B cells promote T-cell-dependent antitumor immunity, thereby enhancing the efficacy of chemotherapy.250 Additionally, Furthermore, pathological antibodies secreted by B cells bind to the HSPA4 receptor on the surface of tumor cell membranes, thereby initiating downstream signaling pathways that activate the NF-κB pathway in tumor cells. This activation results in the expression of target genes HIF1α and COX2. The former promotes the expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in tumor cells, while the latter induces lymph node stromal cells to secrete the chemokine SDF1α. Consequently, this process fosters the formation of a pre-metastatic microenvironment and directs tumor cells toward the draining lymph nodes.251

Tumor dormancy and reactivation

The dormancy and reactivation of long-established disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) in distant organs following primary tumor resection constitute a pivotal factor contributing to tumor recurrence and pose a significant challenge in antitumor therapy.136,252,253,254 Breast cancer continues to recur 5-20 years post-treatment, particularly in ER+ breast cancer cases.255,256 The implication is that the distal site DTCs have remained dormant for numerous years before the clinical detectability of the tumor.257

Previous investigations have elucidated specific mechanisms underlying the dormancy and reactivation of breast cancer cells,258,259,260,261,262 while recent discoveries have further enhanced our comprehension of these phenomena. Type III collagen secreted by breast cancer cells can act as a pivotal “switch” in the ECM. When present in abundance, it sustain tumor dormancy, as its disruption promotes tumor cell proliferation through DDR1-mediated STAT1 signaling.263 Researchers have discovered that NK cells maintain the dormant state of tumor cells within the liver. Excessive accumulation of activated hepatic stellate cells inhibits the proliferation of NK cells, resulting in the activation of tumor cells and subsequent macroscopic liver metastasis.264 Moreover, in the liver metastasis model of breast cancer, the interaction between NK cells and activated hepatic stellate cells (aHSCs) also serves as one of the “switch” of tumor dormancy. On one hand, IFN-γ secreted by NK cells sustains tumor dormancy. On the other hand, the chemokine CXCL12 secreted by aHSCs can induce the quiescent state of NK cells through its homologous receptor CXCR4, thereby triggering the activation of tumor cells. In the breast cancer lung metastasis model, the platelet-derived growth factor C (PDGF-C) level in the microenvironment increases when lung tissue becomes senescent or fibrotic. PDGF-C activates fibroblasts, reactivating dormant breast cancer cells in the lung and thereby accelerating metastasis formation.265

Furthermore, by regulating stem cell properties in breast cancer cells, long non-coding RNA NR2F1-AS1 facilitates local diffusion while inhibiting lung metastasis activation, ultimately promoting dormancy among breast cancer cells during metastasis.266 When breast cancer metastasizes to the brain, DTCs are located on the endfeet of astrocytes. At these sites, laminin-211 secreted from astrocytes binds to dystroglycan, a non-integrin receptor encoded by DAG1 on the surface of DTCs, promoting DTCs quiescence.267 Metabolism is closely linked to tumor dormancy. High levels of the transcription factor NRF2 can induce metabolic reprogramming in dormant tumor cells, re-establishing redox homeostasis and de novo synthesis of nucleotides, accelerating the activation of tumor cells and tumor recurrence.268 The specific mechanisms underlying early occult metastasis in breast cancer remain unknown. The primed pluripotency transcription factor ZFP281, regulated by FGF2 and TWIST1, is a key factor in the dissemination and dormancy of early DTCs. ZFP281 inhibits the proliferation of primary breast cancer but drives the epithelial-mesenchymal transition process, thus promoting metastasis. Once tumor cells reach distant metastatic sites, ZFP281 maintains tumor dormancy and prevents tumor proliferation over extended periods via the induction of the class IIcadherin 11.269 Unlike the classical view of the metastasis cascade model, this reveals a novel mechanism of metastatic dormancy.

Diagnosis of breast cancer: technological advancements

With the continuous emergence of new technologies, the diagnosis of breast cancer has gradually moved from the traditional imaging era to the new era of AI, slice multiple staining, and so on. Here we introduced the role of new technologies in the diagnosis of breast cancer in recent years.

Conventional diagnosis of breast cancer

The routine diagnosis of breast cancer primarily involves imaging examinations, pathological examinations, and clinical physical examinations. The objects of clinical physical examination include the breast, regional lymph nodes, and distant metastases. Imaging examinations include bilateral mammography and ultrasound examination of the breast and regional lymph nodes, while magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not routinely recommended.270,271

High-throughput screening technologies

Despite the power of conventional diagnosis technologies, it should be noted that there is a disease case set called occult breast cancer, which cannot be detected by imaging. ctDNA, which is derived from the release of tumor cells,272 is a part of the cfDNA library released after cell apoptosis or necrosis. In recent years, the wide application of high-throughput analysis technology has made ctDNA a promising biomarker for screening and diagnosis of breast cancer.273,274,275,276,277

Recently, researchers have carefully studied the power of ctDNA to diagnose breast cancer. A meta-analysis that included 24 studies indicated that the average sensitivity and specificity of cfDNA as a diagnostic tool were 70% and 90%,278 respectively. Another more comprehensive meta-analysis, which included 29 studies, indicated that the sensitivity and specificity reached 80% and 88%, respectively.279 These data confirmed the powerful ability of cfDNA/ctDNA as a diagnostic tool for primary breast cancer.

The diagnosis of advanced breast cancer is also important. In one study, a significant increase in the ctDNA portion was observed 12 weeks before the clinical progression of breast cancer leptomeningeal metastasis (BCLM).280 Another study on BCLM showed that the quantification of ctDNA in the participants’ cerebrospinal fluid achieved a remarkable 100% sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing BCLM, exceeding the traditional “gold standard” cytology method.281 These data emphasize the critical role of ctDNA in the diagnosis of advanced breast cancer, especially in the case of meningeal metastasis.

Digital pathology and AI-assisted diagnosis

Digital pathology makes analyzing data from pathological samples easier and provides a deeper understanding of the collected data. Digital methods have higher efficiency in collecting, integrating, and analyzing data than traditional technologies. It has excellent potential to achieve more reliable and accurate data processing for data of larger scale.282 Multi-omics (including digital pathology) data of a large cohort of Chinese breast cancer patients has contributed to the precision treatment of breast cancer.283

For AI algorithms, high-quality training images are required. Qualitative evaluation of AI can quickly and accurately identify cell types and provide corresponding tissue morphology and biological patterns. Integrating AI into screening and diagnostic methods, such as biopsy, can significantly improve the success rate of breast cancer screening and/or treatment. Machine learning and deep learning are the key aspects of AI in breast cancer imaging. Machine learning is used to store a large dataset, which is then used to train prediction models and interpret generalization.284 Deep learning is the latest branch of machine learning, which classifies and recognizes images by establishing an artificial neural network system.285 A prospective and population-based study found that compared with a double reading by two radiologists, replacing one radiologist with AI could induce a 4% higher non-inferior cancer detection rate.286 Similar findings were also observed in another randomized controlled trial.287 In another diagnostic accuracy cohort study, a mobile phone-AI-based infrared thermography showed significantly higher diagnostic accuracy than traditional human readers.288

Multiplex immunofluorescence staining

In recent years, immunotherapy has shown promise in treating breast cancer.289,290 There is growing evidence that the difference in immune responsiveness is due to the heterogeneity of the tumor microenvironment.139 The traditional techniques for evaluating the tumor immune microenvironment, including gene expression profiling, flow cytometry, and conventional immunohistochemistry, have limitations. For example, transcriptome profiling and flow cytometry cannot obtain in situ spatial information of molecules and cells in the microenvironment. Unlike the qualitative analysis of conventional immunohistochemistry, multi-fluorescence immunohistochemistry technology has made technological innovations in multi-label staining, spectral imaging, and intelligent analysis, overcoming the limitations of traditional pathological single-label and qualitative analysis, as well as the technical shortcomings of gene expression profiling and flow cytometry that cannot obtain in situ spatial information of proteins and cells. It has obvious advantages that cannot be replaced in analyzing the tumor immune microenvironment. By using multiple fluorescence immunohistochemistry techniques, multi-channel information about cell composition and spatial arrangement can be obtained, enabling high-dimensional analysis of the tumor microenvironment and providing precise diagnosis and subsequent targeted therapy assistance for tumors.291,292 Clinical trials regarding multiplex immunofluorescence staining are currently limited. However, this technology has now been applied in basic experiments. For example, in a recent pilot study of patients with early-stage breast cancer who received neoadjuvant talazoparib, multiplex immunofluorescence staining was performed to examine the changes in tumor immune microenvironment.293 In another study, multiplex immunofluorescence imaging was also performed in combination with single-cell sequencing to depict the microenvironment of primary breast cancer.294 We believe that in the near future, multiplex immunofluorescence imaging will become a powerful weapon for the precision treatment of breast cancer.

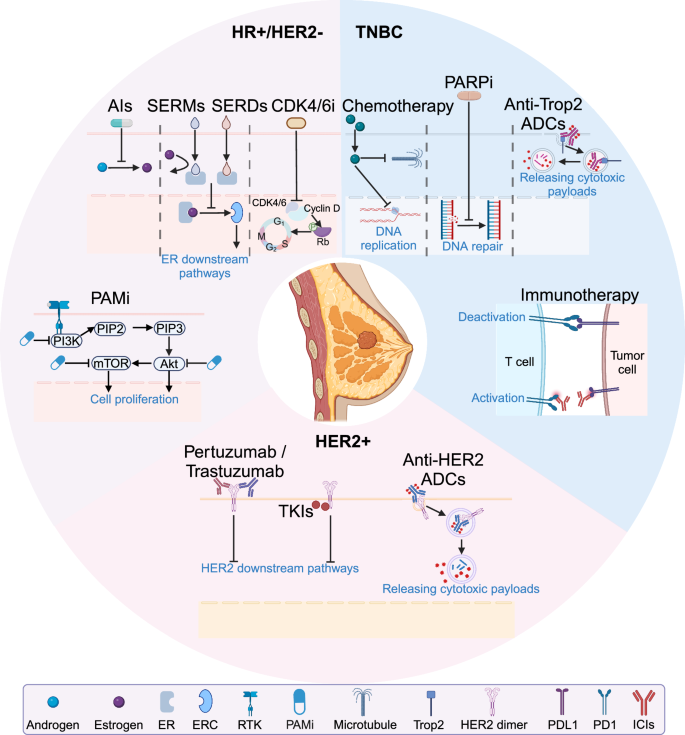

Treatment of breast cancer: emerging strategies and therapies

Advances in precise molecular subtype diagnostics have accelerated the development of systemic treatment strategies for breast cancer in recent years, particularly in the areas of endocrine therapy and anti-HER2 therapy. The continuous introduction of new drugs and clinical trials has significantly improved patient survival outcomes. As more drugs enter the neoadjuvant treatment platform, neoadjuvant therapy enhances both the precision and minimally invasive approach of local treatments. Additionally, the efficacy of the neoadjuvant platform is validated through local treatment, offering a robust foundation for adjusting the intensity and duration of subsequent adjuvant therapy.

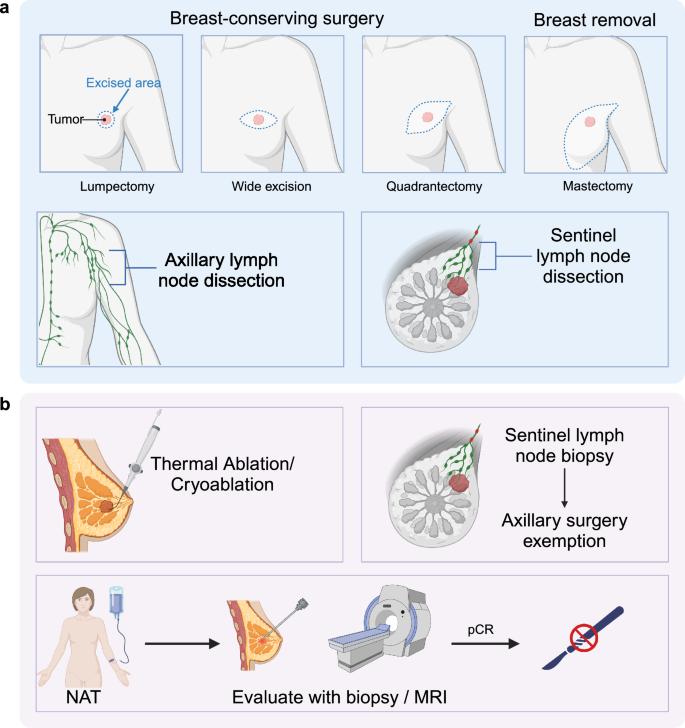

Local treatment

Local treatment of breast cancer is undergoing revolutionary changes, with the primary goals being precise excision within the smallest possible margins and the minimization of trauma.295 An increasing number of patients are moving from mastectomy to breast-conserving surgery (BCS) and from axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) to sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). However, this progress remains insufficient. With advancements in technology and improvements in the neoadjuvant platform, the possibility of less invasive or even surgery-free treatments is becoming a reality. Based on these principles, numerous innovative explorations are emerging in both the surgical and radiotherapy fields (Fig. 5).

Surgical treatment for breast cancer. Traditional treatments for breast cancer include breast conservative surgeries and mastectomy, while axillary surgeries include axillary lymph node dissection and sentinel lymph node dissection. Currently, there have been some novel approaches for breast cancer treatment. Thermal ablation/cryoablation is a potential non-surgical technique for tumor destruction that can possibly replace surgical excision in some situations. Moreover, there has also been an emerging concept of using neoadjuvant therapy (NAT) to eradicate tumors and completely avoid surgery, which requires core biopsy or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to confirm no residual tumor. Sentinel lymph node biopsy allows safe axillary lymph node dissection exemption for certain patients. pCR pathological complete response. The figure was created with Biorender.com

Breast cancer ablation therapy: thermal ablation/cryoablation

Thermal ablation and cryoablation, as non-surgical techniques for tumor destruction, are increasingly being utilized for the local treatment of early breast cancer. While direct comparisons between ablation and surgical excision are limited, numerous observational studies indicate that ablation provides acceptable rates of local control and long-term survival, along with superior cosmetic outcomes.296 Currently, thermal ablation techniques for breast cancer include radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation, laser ablation, and high-intensity focused ultrasound.297,298,299,300,301 Cryoablation employs extreme cold by inserting a cryoprobe into the target tissue, alternating between freeze-thaw cycles to form an ice ball that destroys the target lesion.302 The primary concern regarding these ablative techniques is whether they achieve efficacy comparable to breast-conserving surgery (BCS).303 Tumor size plays a crucial role in evaluating safety; while some studies include patients with larger tumors, more restrict inclusion to tumors no larger than 2 cm to ensure safe rates of local recurrence-free survival.302,304,305,306,307 Another critical factor is assessing post-ablative effectiveness, particularly the rate of complete destruction. Early studies used confirmatory surgical excision immediately after non-surgical ablations, employing dual staining methods to enhance pathological accuracy. Later studies often utilize magnetic resonance imaging and contrast-enhanced ultrasound to evaluate residual lesions intraoperatively and post-operative lesion absorption and recurrence.308,309,310,311

Recent research goes beyond local treatment and explores the immune response against tumors induced by ablation.312 During the thawing phase of cryoablation, tumor cells within the ice ball release antigens, nucleoproteins, and cytokines, recruiting macrophages and NK cells to stimulate an immune response. This leads to the release of antigen-presenting cells into the cryoablated tissue.313,314,315 Moreover, the release of tumor-specific antigens triggers specific immune responses against the tumor itself, resulting in a reduction of distant metastatic lesions known as the “abscopal effect”.316,317 Some centers are attempting to integrate ablation technology with immunotherapy or other targeted inhibitors to harness these treatments’ synergistic effects and safely activate the immune system, which could be pivotal in further enhancing long-term prognosis.318,319

Exploration of eliminating breast surgery

The surgical management of breast cancer is evolving towards a “less is more” approach, with a focus on preserving the Pectoralis muscle, conserving the breast tissue, and sparing the axillary lymph nodes. This advancement can be attributed mainly to conceptual innovations, particularly the introduction of neoadjuvant therapy, which provides more patients with the opportunity for surgery and breast conservation.320 However, even minimally invasive BCS can result in irreversible damage. Therefore, there has been an emergence of the concept of using neoadjuvant therapy to eradicate tumors and avoid surgery completely. Early clinical trials compared radiotherapy to breast surgery based on clinical complete response as the criterion for inclusion. After a follow-up period exceeding ten years, it was found that the local-regional recurrence (LRR) in the group receiving radiotherapy alone was slightly higher than those who underwent BCS followed by radiotherapy or mastectomy.321,322 As a result, some studies have utilized ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted core biopsy (VACB) to obtain larger and more extensive specimens while reducing the false-negative rate to 0–5%.323,324 This has increased confidence in continuing standard neoadjuvant therapy for patients with cT1-2N0-1M0 in HER2+ breast cancer or TNBC. By confirming no residual tumors through multi-site VACB under ultrasound guidance in areas where imaging shows residual lesions <2 cm, these patients can avoid open breast surgery.325 In highly selected breast cancer patients, exemption from breast surgery is considered a potential future direction. Although some studies confirm the feasibility of exempting patients who achieve pCR after neoadjuvant systemic therapy under rigorous evaluation using ultrasound or MRI,323,326,327 this approach is constrained by regional development levels and technological disparities. Consequently, not all centers support this radical decision in similar studies.328,329

Exemption of axillary surgery in breast cancer

ALND has traditionally been a crucial component of breast cancer surgery. However, the theory proposed by Professor Fisher that breast cancer is a systemic disease from its onset has raised doubts about the necessity of ALND. The NSABP B-04 study revealed that 40% of patients in the radical mastectomy group had axillary lymph node metastasis, while only 18.6% of patients in the simple mastectomy group developed axillary recurrence and subsequently underwent ALND.330 Although the LRR rate was higher in the simple mastectomy group than in the radical surgery and mastectomy combined with axillary radiotherapy groups, there were no statistically significant differences in overall survival (OS) and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS).331 This study provided a theoretical foundation for further exploration. In the NSABP B-32 study, comparing the SLNB group and SLNB + ALND group showed no significant differences in OS, disease-free survival (DFS), distant disease-free survival (DDFS), and LRR over an extended follow-up period.332 Subsequently, the IBCSG 23-01 study demonstrated that omitting ALND is safe and reliable when micrometastasis is found in SLNB.333 When considering whether to proceed with ALND after macrometastasis is detected in sentinel lymph nodes, the ACOSOG Z0011 included patients with confirmed cT1-2N0 breast cancer who underwent BCS. Regardless of whether they were followed up for 5 years or 10 years for OS, the SLNB group was found to be non-inferior to the ALND group in both follow-up periods.334 The AMAROS study included 18% of patients who underwent mastectomy. Although there were no statistically significant differences in DFS and OS between the radiotherapy and ALND groups over a ten-year follow-up, the primary endpoint, the 5-year axillary recurrence rate, was significantly higher in the SLNB group compared to the ALND group, failing to meet the predefined non-inferiority margin.335 The SENOMAC study addresses the limitations of prior research, including 36% of patients who underwent mastectomy. With OS as the primary endpoint, comparisons between the SLNB and ALND groups reveal no significant differences in breast cancer-specific survival, recurrence-free survival, or OS.336,337

Furthermore, the latest SOUND study employs a more pioneering approach. For patients with tumors ≤2 cm in diameter who are candidates for BCS and radiotherapy, preoperative ultrasound is used to exclude axillary lymph node metastasis. The 5-year DDFS, DFS, and OS show no statistical differences between the non-axillary surgery and SLNB groups.338

Changes in indications for radiation therapy in low-risk patients

It is widely acknowledged that adjuvant radiotherapy following BCS significantly reduces the cumulative recurrence rate in the ipsilateral breast. However, radiotherapy-related side effects are frequently encountered. Therefore, identifying low-risk patients who may be exempt from radiotherapy holds great clinical research significance.20 The CALGB 9343 study focuses on elderly low-risk HR+ breast cancer patients, comparing the outcomes of tamoxifen plus radiotherapy versus tamoxifen alone. The results indicate that while the radiotherapy group slightly improves LRR, this does not translate into a survival benefit.339 The LUMINA study extends the range to include low-risk breast cancer patients aged 55 and older who undergo only BCS and endocrine therapy. The 5-year LRR is 2.3%, with an OS of 97.2%.340 The PRIME 2 study enrolls patients aged ≥65 years, consistent with previous findings, the radiotherapy group demonstrates a lower ten-year LRR but no significant OS advantage.341,342 For elderly low-risk patients, the primary concern is how to predict the survival benefits of radiotherapy using limited information while avoiding its potential side effects.

Defining patient risk based solely on clinicopathological factors is a straightforward and practical approach, but it does have certain limitations. The IDEA (Individualized Decisions for Endocrine Therapy Alone) study represents the first application of genomic testing (Oncotype DX 21-gene) to younger postmenopausal patients who undergo endocrine therapy after BCS. This study assists in making individualized clinical decisions regarding exemption from radiotherapy and endocrine therapy alone.343 Other ongoing studies, such as the NRG-BR007 DEBRA trial (NCT04852887), also incorporate the Oncotype DX 21-gene recurrence score, whereas the PRECISION (NCT02653755) and EXPERT (NCT02889874) studies employ PAM50 testing. Exploring additional biomarkers will likely become a key focus in future clinical trials to accurately select patients with low risk of local recurrence and further stratify these already low-risk individuals.

Systemic treatment for HR+/HER2− breast cancer

HR+/HER2− breast cancer represents the most common subtype and is associated with the most favorable prognosis. In recent years, as the prognostic stratification of early breast cancer has become more precise, it has become a clinical consensus to tailor the intensity and duration of endocrine therapy according to risk stratification. With advancements in molecular diagnostics, a deeper understanding of HR+/HER2− breast cancer has been achieved, and several pathway inhibitors, as well as immunotherapies, are showing increasing promise.

SERMs and SERDs

Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), is the classical treatment for HR+/HER2− breast cancer. Fulvestrant, an agent that acts both as an inhibitor of estrogen receptors and a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERDs), gained approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002 for the treatment of advanced hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, marking the advent of a new era in endocrine therapy.344,345,346 Although some studies indicate that breast cancer patients with ER expression between 1% and 10% may exhibit reduced sensitivity to endocrine therapy, the threshold of 1% ER expression is still used in most current clinical practices to determine the need for endocrine therapy.347