Understanding the development of a functional brain circuit: reward processing as an illustration

Introduction

Accurate evaluation of reward is critical for adaptive behavior across the lifespan and is altered in numerous psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorders, depression and schizophrenia. Many of these disorders have their roots in early life, when the brain is in a state of heightened plasticity and vulnerability to environmental factors. To develop effective age-specific interventions and therapies for illnesses resulting from early life insults, we must first understand how the immature brain processes environmental signals to guide behaviors. We must then understand how these circuits change to accommodate maturing sensory signals, new needs of the organism, and richer interaction with the environment to support more complex behavioral profiles. Based on this, we can begin to understand how disturbance in developmental processes may ultimately manifest as pathology.

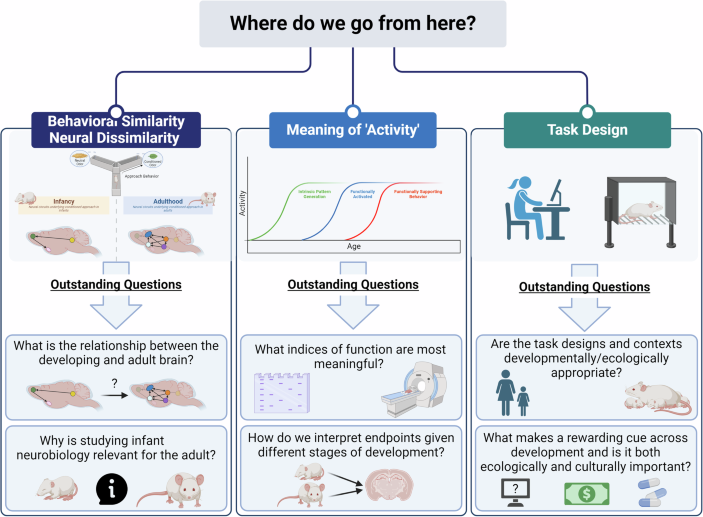

Much of what we know about reward processing is based on anatomical, physiological, and behavioral profiles from intact adult human and non-human animal studies. In developmental studies, behavioral responses and regional activation measures are often interpreted in the framework of adult circuitry. However, still developing are sensorimotor integration, regional connectivity between key nodes identified as critical for adult reward processing, and cellular composition of these brain regions. Here, we advocate for a developmentally-constrained approach, where we focus on cross-species research to better define the relationship between developmentally evolving behavioral profiles and the neurobiological structures supporting these behaviors. Our major focus is on rodent research, as this literature provides a more fine-grained description of neural circuit development. However, we refer to the human developmental literature to provide translational links.

We argue that re-framing investigations of early reward within the context of nonlinear circuit development and its transitions could identify (1) the roots of pathology and (2) novel targets for therapeutics and interventions. More specifically, this approach takes into account unique, age-specific brain network functions that promote adaptive or maladaptive behaviors as environmental demands change from infancy through childhood. This consideration is critical for defining, measuring, and interpreting early reward function. We survey the extant literature and ask, how are rewarding stimuli experimentally defined for infants and children and how are reward tasks adapted for them? Do the adult-defined neural reward circuits also support early reward behavior? Finally, how can early circuit perturbation impact infant and adult circuit function?

The literature indicates that although some reward behaviors appear mature in infancy, the brain regions that infants and adults use to support these behaviors may differ. Furthermore, what is rewarding to an infant is not necessarily rewarding to older individuals, and vice versa. We use the term “developmental transition” to primarily indicate a change in environmental demands that is concomitant with a change in behavior and neurobiology, e.g. the transition from caregiver-oriented behavior to peer-oriented behavior. By reconsidering developmental transitions in the neurobehavioral assessment of reward, we put forth that this developmental niche is critical for defining the concept of reward and dissecting its neural substrates. In doing so, we hope to challenge general assumptions that impede our understanding of the developing brain.

Although our proximal focus is reward processing, these questions can be applied to any developmental function. As such, we hope that our approach can provide not only concrete considerations for designing age-appropriate reward tasks, but also provide a general conceptual framework for studying brain function in early life and caution against using adult brain circuits to explain early-life behaviors.

Challenges in mapping adult-defined reward circuits onto infants and children

In adults, the canonical definition of a rewarding stimulus involves three components: wanting (incentive salience, or motivating approach behavior), liking (eliciting pleasure or hedonic sensation), and driving associative learning (classical and instrumental conditioning) [1]. A rich body of literature has demonstrated that in adults and adolescents, dopamine plays a central role in reward processing, particularly through the mesolimbic dopamine system, which includes the ventral tegmental area (VTA) ventral striatum (predominantly the nucleus accumbens, NAc), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and amygdala [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Beyond this circuitry, structures such as piriform cortex [8] entorhinal cortex [9], insula [4], orbital frontal cortex [10] and dorsal striatum [11] are all involved in the learning and expression of reward learning in adults. Although reward learning can occur independently of dopamine (DA), and serotonin (5-HT) plays a role in some forms of adult reward learning, here we focus on differences in DA involvement between infants and adults given the available developmental evidence on this specific substrate of reward neurobiology.

These brain regions have been included in the reward neural pathway based on several types of evidence. In nonhuman animal research, experimental manipulations show that these regions are necessary, sufficient, or both in producing wanting, liking, or associative learning in adolescents and adults (see reviews above). These regions have also emerged in human neuroimaging data during reward tasks (e.g. [12, 13]. However, most neuroscientists would agree that neural activation alone is a limited metric of brain function. The infant brain also shows reward-sensitive activations, but caution must be taken when interpreting these patterns. This caution is especially important during development, when waves of internal and external inputs are common that scaffold, program and organize emerging neural systems, but this activity does not indicate functioning as in sufficient or necessary in the adult sense.

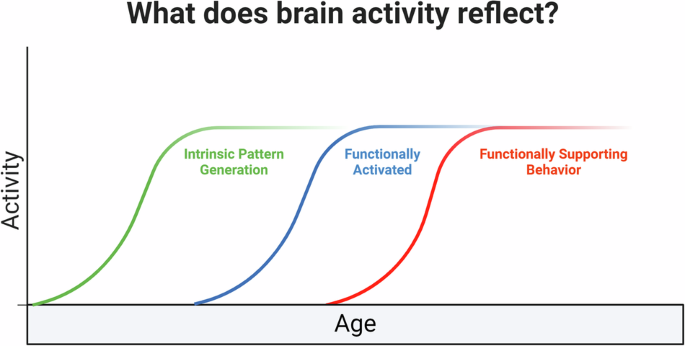

Although the proliferation and differentiation of cells into a pattern that meets identifiable regional landmarks in the adult brain is a critical step in brain maturation, structural presence does not necessarily indicate functional efficacy. Indeed, structural maturity permits brain areas to generate intrinsic signals and respond to the environment prior to functional maturation and generation of behavioral output (Fig. 1). This can be illustrated clearly using the visual system: before vision functionally emerges, and even before the eyes are open, waves of intrinsic activity are present in the retina that guide brain development [14]. These waves precede stimulus-evoked activity (sight), which then ultimately guides behavior (looking) after functional maturation of the network. In other words, these intrinsic waves producing neural signals cannot be interpreted through the lens of mature adult neuroimaging and directly transferred to interpretation of the perinatal brain. Rather, neural signals can reflect programming of the brain at a time when neural activity cannot contribute to behavior [15]. In terms of reward circuitry, an intrinsic wave of activity may be observed in the region to be later identified as the NAc in a blind and deaf infant rat (wave 1). This same cluster of cells may then express immediate early genes following approach toward the caregiver (wave 2). However, lesioning this region will not impact approach behavior, indicating it is neither sufficient nor necessary to support behavior as required in wave 3.

In this article, we use the concept of reward processing to reconsider brain function during development. Expression of activity markers in a brain region, such as BOLD response in humans or immediate early gene expression in non-human animal tissue, is often interpreted to mean that a brain region is functional in a given task. However, this is simplistic and may be even incorrect. During development in particular, brain activity can reflect patterns of intrinsic activity (wave 1), which precede stimulus-evoked activity (i.e. functionally activated, wave 2). Finally, brain activity markers can reflect neural control over specific functions (i.e. functionally supporting behavior, wave 3). However, the burden of proof for this last measure is high and requires gain- and loss-of function approaches. This is true at all stages of development. Thus, caution is needed when interpreting markers of brain activity, especially during early life when waves 1 and 2 are central processes of brain network building.

As such, the level of activity markers alone, such as immediate early gene expression or a blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) response in the developing brain, is a limited assay without gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies to assess necessity and sufficiency. This highlights the importance of cross-species research to test hypotheses to better understand general principles of neural development in the developing human brain.

With reward processing and neurobiology thus defined in the adult, we may simply ask if the same system supports reward function in early life. However, several key questions must first be considered within the context of development. First, how is reward assessed in early life? Berridge’s three components (wanting, liking, driving associative learning) are not typically used as prerequisites during infancy and childhood, suggesting an alternative set of conditions may be instructive for defining reward. Second, does behavioral similarity imply circuit continuity across development? Behavioral expressions of reward function, including sucrose responsivity and complex processing of rewards associated with classical and operant conditioning, are seen from a very young age (newborn humans and infant rodents), often paralleling adult expression [16,17,18]. However, it would be premature and potentially misleading to assume that brain circuits identified in adults are functional in the infant brain when attempting to explain behavioral findings across development.

With these considerations in mind, we argue for a re-framing of both the questions asked and the answers accepted in defining the developing reward circuit. Below, we review the neuroanatomical evidence for how infants and children process and learn about reward cues, with a focus on social stimuli. We focus primarily on findings from rodents, as this literature provides a more detailed, fine-grained understanding of the neural circuits and developmental time course of the infant reward system. We review findings on humans, when available, to point out equivalencies and divergences that could promote research across species.

What is rewarding to an infant?

Social cues, particularly those associated with the mother, are strong elicitors of approach and learning in early life. The ecological niche of altricial infants elevates the caregiver, the source of survival, as the most powerful motivating stimulus [19, 20]. Based on the above definition of reward, it is indeed the caregiver, and cues associated with the caregiver, that produce associative learning, elicit anticipatory appetitive behavior (wanting/incentive salience), and/or produce hedonic responses (indexed by rigor of consummatory responses). As such, much of the work dissecting the underlying neural circuitry of reward involves the caregiver as a stimulus. However, viewing the complex figure of the parent simply as a social reward would fail to account for specific sensory cues and behaviors emitted by the parent and received by the infant, all supported by a distinct circuit from the adult. In this section we review the behavioral and neuroanatomical evidence for the infant reward function, focusing on the distinction between learning cues that are components of the complex caregiver stimulus (maternal milk, odor, tactile stimulation), and cues that are ostensibly not evocative of the caregiver (drugs, food pellets).

Appetitive conditioning to caregiver-associated cues in humans and rodents

In both human and rat newborns, the maternal odor elicits approach behavior [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. New maternal odors can also be learned via classical conditioning in humans and rodents. In newborn children, a perfume worn by the lactating mother is quickly learned and preferred [29] and skin-to-skin contact with the mother immediately after birth has been shown to increase approach (i.e., mouthing) to her milk odor four days later [24]. Newborns who were exposed during breastfeeding to a chamomile-scented balm in the first 4 days of life exhibited more wanting and liking behaviors for that scent (i.e., less negative facial expressions and more exploration, mouthing, and preferential choice of the odor) even 1.5 years later [30] (however, less negative facial expressions could reflect habituation). This process can be mimicked with classical conditioning in newborn children: a few pairings of a novel odor with tactile stimulation (mimicking massage) produced subsequent preference for that odor (headturns, mouthing), which was not induced by unpaired presentations [31, 32].

Causal mechanisms for learning the new maternal odor have been uncovered using rodents: pairing a neutral odor with stimuli evoking discrete aspects of maternal care (e.g. milk, stroking with a paintbrush to mimic grooming) outside the nest causes the infant to approach that odor [16, 33] but this odor also can substitute for the natural maternal odor to support the maternal odor-dependent nipple attachment [34]. One unexpected finding was that there are a large range of stimuli that can be used as a reward to support classically conditioned odor preference learning, including stimuli considered rewarding, such as milk and warmth, but also stimuli that typically support aversions, such as presumably painful 0.5 mA shock to the tail or foot or tail pinch [34,35,36]. These stimuli appear to be associated with the mother and maternal behavior, with pain potentially associated with rough maternal care, such as stepping on pups. This does not occur in adults, ending at postnatal day (P)15. As will be discussed below, this diverse reward categorization in infancy converges within the neural basis of infant odor preference learning.

Neural circuits promoting learning of caregiver-associated cues eschew the dopaminergic system

Evidence from rodents

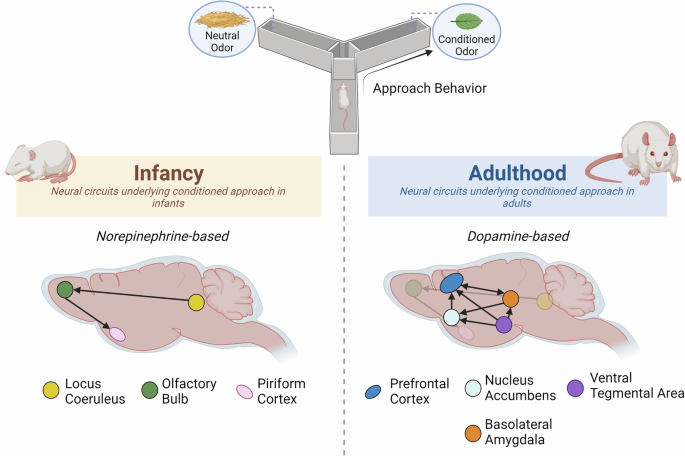

Although the appetitive learning of cues associated with the caregiver in both rodents and humans illustrates reward processing, the neural circuits supporting this system appear to involve circuitry distinct from the reward circuits defined in adulthood. This reward learning in infants is a highly robust system that, at least according to rodent data, involves unique functioning of a circuit including the locus coeruleus, anterior piriform cortex, and olfactory bulb. Notably, the VTA, NAc, and other regions critical for adult reward function are not involved in this basic learning process.

During the first nine days of life, rat pups learn a new maternal odor (stimulus that elicits approach and maternal odor-dependent nipple attachment) through a simple substrate whereby copious amounts of norepinephrine (NE) from the locus coeruleus (LC) flood the olfactory bulb (OB) when odors are paired with cues mimicking maternal care (e.g. milk, warmth, stroking, but also shock) [37,38,39]. The axons of OB mitral cells project directly to the piriform cortex [40,41,42,43], which plays an important role in assigning hedonic value to a learned odor in a region-specific manner. In particular, the anterior piriform is engaged by odors learned during this sensitive period, while the posterior piriform is engaged in response to more complex learned odor aversions in >P10 pups and adults [44,45,46]. The sensitive period ends when pups are around 10 days old, as the LC exhibits auto-inhibition and habituation to repeated stimuli presentation, with NE release becoming more adult-like. After P10, NE from LC takes on a modulatory role in odor learning that resembles what has been described in adult rats [47].

Beyond NE, the OB receives additional extrinsic monoaminergic inputs that alter the excitation/inhibition balance and impact olfactory learning. During the first postnatal week of life, dense serotonin (5-HT) inputs from the raphe nuclei are detected in all layers of the rat OB [48]. Depletion of 5-HT in the OB impairs appetitive olfactory learning in newborn rats, suggesting that 5-HT in the OB is involved in normal olfactory learning [49]. Furthermore, presence of the 5-HT2 receptor subtype is also used for the acquisition of appetitive olfactory learning, but not for the consolidation or retrieval of learning [50]. However, high levels of NE input can induce odor learning in intrabulbar- 5-HT-depleted newborns, indicating that NE can bypass 5-HT function [51]. Conversely, injection of 5-HT2 receptor agonist does not induce odor learning [52]. In addition, NE β-adrenoceptors and 5-HT2A colocalize and interact mainly in OB mitral cells. 5-HT has thus been suggested to facilitate direct NE action on mitral cells during the processing of unconditioned stimulus information [53].

Altogether, this unique infant circuitry promotes consummatory behavior towards cues that enhance approach and proximity seeking behaviors towards the caregiver. Importantly, infant reward learning relies heavily on NE, rather than the adult-defined canonical “reward circuitry” involving dopamine (DA) signaling from the VTA to NAc. Indeed, while dopaminergic inputs to the OB are important for adult appetitive learning [54, 55]. these projections exhibit late functional maturation, around the third postnatal week [56, 57] and are likely not functional in supporting learning in the perinatal infant, when classical conditioning has been robustly demonstrated. Therefore, it seems unlikely that dopaminergic inputs to the OB play a role in early olfactory learning. Furthermore, this learning system has not been previously addressed in terms of supporting “reward”, but rather “attachment” learning about the mother and nipple attachment using classical conditioning outside of the nest [58]. Therefore, it is possible that confusion may arise from a semantic issue in defining reward circuitry in early life, as one considers the transitions associated with maturation and changing ecological niches. However, there is clear procedural (classical conditioning) and behavioral output (preference, approach learning) continuity across development to provide a framework for divergence in assessment of supporting neural circuitry.

For young juvenile rodents, it may be that dopaminergic systems are not yet established enough to process rewards, with such processing occurring via the NE and 5-HT systems described above instead. Indeed, DA innervation, receptor density, and transporter density increases across infancy and juvenile developmental stages in both PFC and striatum of rats, peaking during adolescence [59]. As mentioned above, non-DA systems also contribute to reward learning in adults. For instance, research by Saunders and Robinson showed that goal-tracking behaviours, which are typically considered reward-driven, can occur independently of dopamine [60]. Additionally, Winstanley et al. [61] demonstrated that 5-HT significantly influences decision-making and delayed reward processing in adults. Nevertheless, the available evidence on infant reward-like behavior, approaching caregiver cues, suggests that a focus on DA signaling highlights the distinct neurobiology serving this behavior across the lifespan.

Evidence from humans

Whether the canonical adult DA reward system and/or NE are involved in human infants’ reward processing and attachment learning remains an open question. One study in newborns found increased BOLD activation to a rewarding odor (formula milk) in the cerebellum, and for most newborns also in the piriform cortex, thalamus, orbitofrontal cortex, and insula [62]. Another study using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) found increased orbitofrontal activation in newborns in response to own mother’s milk odor compared to formula odor [63]. Other studies found an increase in newborns’ resting-state functional connectivity between the caudate nucleus (part of the dorsal striatum) and sensory regions in response to pleasant or familiar music [64, 65], which is highly rewarding to humans.

These findings point to some similarities with rodent findings (e.g., piriform cortex activation) and to activation of memory-related regions (e.g., perirhinal and entorhinal cortices) and interoception integration regions (e.g., insula; [19]), but not necessarily to the canonical adult reward system. Of particular interest is the involvement of the caudate nucleus and putamen, which together form the dorsal striatum. These regions play a central role in sensorimotor responses to emotional stimuli [64] and their activation is driven mainly by DA [66]. However, they are not considered part of the canonical mesolimbic reward system, which depends mainly on the ventral striatum, and so it is yet to be determined whether these patterns indicate dopaminergic activation specific to reward processes.

Overall, these studies across species suggest that infants can demonstrate behaviors that look like appetitive learning of rewarding stimuli, similar to adults. However, neural circuit assessments suggest that the mesolimbic DA system does not control these behaviors (Fig. 2). Therefore, these findings provide a striking example of the premise that behavioral similarity does not imply circuit continuity.

Across the lifespan, rats can learn to approach a previously neutral odor through associative conditioning. However, this involves distinct neural circuits in infancy compared to adulthood. In infancy, pups learn to approach odorant stimuli through a simple circuit that relies heavily on the NE system; this process may promote quick learning of new caregiver-associated cues. In adults, appetitive learning occurs through the canonical reward-associated circuitry involving mesocorticolimbic DA signaling. As mentioned above, this scheme does not include all forms of adult reward learning, which may involve other circuits.

If striatal DA is not centrally involved in infant reward function, what is it doing?

Evidence of DA involvement in the response to the parent

Consideration of the age-specific dependence on parental care may aid in understanding the role of DA in infancy. In early life, there is a robust bias towards approaching caregivers, who have the power to suppress the late-developing fear/avoidance circuitry. In rodents, DA mediates the suppression of the amygdala-dependent fear system, with the caregiver also suppressing activity of the HPA axis, VTA, and NAc before P15 [67, 68]. The caregiver is similarly able to buffer the stress response and amygdala activation in human children [69, 70]. Furthermore, cues paired with an aversive stimulus when the caregiver is present can elicit approach in four-year-olds, suggesting the caregiver’s presence switches aversion conditioning to reward conditioning (although the authors called it “attraction learning”) [71]. This study provides a translational example of a phenomenon observed in <P15 rat pups [45]. In the absence of fearsome cues, the presence of caregivers has also been shown to decrease DA turnover in the guinea pig septum [72].

In a study focusing on later infancy [73], 7-month-old human infants showed lower spontaneous eye blink rate (indicating DA activation) to maternal cues compared to a female stranger. While the authors interpreted this finding as indicating higher attention to the mother (not necessarily DA-mediated) [72, 74], a second interpretation could be that during infancy, maternal presence decreases DA, in line with previous findings in rodents and guinea pigs [72, 75].

Non-reward functions and infant dopamine

Similarly to adults, DA has many roles in infancy, including guiding brain development, a process which continues through adolescence in humans [76] and rodents [59]. We have known for decades that maternal inputs decrease pup DA activity [72, 75, 77, 78] and that DA gates amygdala plasticity to promote threat learning [75, 79]. Recent research in infant rodents illustrates that excessive basolateral amygdala (BLA) DA during infancy disrupts social behavior with the mother and peers; circuit dissection using microdialysis and optogenetics showed this occurs through atypical VTA-BLA engagement [74]. In light of the known role of DA in assigning stimulus valence and salience [80, 81], one interpretation is that this failed DA regulation results in persistent changes in evaluating a social stimulus, reflecting altered processing of the mother after adversity. This is consistent with data showing adversity-rearing perturbs maternal regulation of the infant DA system and BLA activation during fear/threat conditioning [68]. Importantly, the VTA-BLA circuit controls peer social behavior as well. In younger pups, adversity-induced VTA-BLA hyper-engagement was associated with decreased approach toward the mother. In contrast, older pups showed an increase in relative preference for a familiar littermate. These developmental alterations may reflect a changing role for DA in social behavior as pups transition from mother-directed social behavior to a balance of avoidance and approach as they prepare for independence and navigating complex social hierarchies. These functions involve evaluating novelty, salience, reward, aversion, and learned safety cues [1, 82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89].

Together, these data indicate that the role of DA in infant reward/attachment learning is distinct from the adult. This may be due to functional/structural immaturity, age-specific function, or a combination of both. In addition, these studies demonstrate the importance of cross-species research that permits assessment of causation using gain- and loss-of-function approaches. Perhaps most importantly, they show that in very early life, association with a caregiver determines whether or not a stimulus is rewarding.

Transition to more adult-like reward circuits as individuals mature

As individuals mature, data across species suggests that social reward processing becomes more adult-like—that is, engages mesolimbic DA circuitry – although the salience of the caregiver as a strong approach motivator remains. To study social reward in more mature rodents, researchers can use a social conditioned place preference task (sCPP), whereby social cues paired with locations can produce a location preference [90]. Juvenile female mice (P17-21) showed a preference for chambers associated with either maternal or paternal odors [91] and this behavioral readout was linked with increased VTA tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in DA synthesis. These results suggest that during this developmental stage, preference for parents is associated with the elevated activity of VTA dopaminergic neurons, in contrast to the DA decrease observed in younger (i.e., infant) pups described above.

Mesolimbic and mesocortical DA signaling in the VTA-amygdala-mPFC circuit also appears to be involved in reward processing as infants mature into childhood. In middle and late childhood (5–12 years old), children show ventral and dorsal striatum and amygdala activation and connectivity with frontal areas during reward anticipation and receipt [92,93,94,95,96,97,98]. Studies comparing typically-developing children and children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have also lent support to this concept (for systematic review, see [99]). As one example, Supekar et al. [100] found that both structural and functional circuit aberrations in the mesolimbic reward pathway are related to parent-report measures of social interaction impairments in children with ASD [100]. The caregiver still holds special significance at this age, as activity in reward/salience processing regions is blunted to mothers’ voices in children with ASD [101].

This behavioral transition from infancy to childhood has been paralleled by activity of the NAc, a canonical component of the adult-defined reward circuitry, suggesting that parental reward processing in the juvenile/childhood period involves more adult-like circuit mechanisms. Abrams and colleagues [12] measured regional responses to mothers’ voices and novel females in children from age 7 to 17 and found that younger children (7–13 years) showed greater neural activity in NAc, and vmPFC, a brain network associated with social valuation, in response to mother’s voice compared with novel female voices [12]. In contrast, adolescents (13.5–17 years) had the opposite trend, with greater neural activity in response to novel female voices compared with mother’s voice in these brain systems. Notably, the importance of the caregiver is not entirely lost as the child matures, though may be more specific to conditions of duress. For example, for adolescents faced with risky versus safe decisions, maternal presence was associated with greater activation of the ventral striatum during safe choices [102]. As an additional developmental consideration, adolescence marks a shift from family-oriented to peer-oriented socialization/rewards concurrent with changes in reward circuit maturation to support exploratory behavior and non-incestuous reproductive behaviors [103].

Together, these findings demonstrate how the developmental niche of the individual and the demands of the social environment can impact what social stimuli are motivating and the brain regions involved. In particular, they highlight how the child reward system is distinct from the infant in its underlying neurobiology yet also distinct from the adolescent and adult in the continued salience of the caregiver. However, these results must also be interpreted with the caveat that activation of a neural circuit cannot necessarily be taken to indicate functional maturity (Fig. 1). It remains likely that fine-tuning of the reward circuitry continues well into adolescence and is influenced by experience with reward [104].

Why is studying the early neurobiology of reward relevant to adult reward-related pathology?

A key takeaway from the studies described above is that distinct neural circuits can support similar behaviors across development. However, a robust literature continually demonstrates that early perturbations, including DA perturbations, produce lasting neurobehavioral impacts [2, 74, 104, 105]. For example, nearly one-third of mental health conditions are associated with exposure to trauma early in life [106]. Yet, following from the above evidence, how can this be true if reward neurobiology differs between infancy and adulthood?

To begin to address this question, we consider the literature on the impacts of early adversity on reward circuits defined in the adult, particularly the VTA and NAc. Both regions undergo prolonged maturation, which leaves this circuit more susceptible to adversity-induced disruptions [2, 107]. One model of pathogenesis suggests that adversity can disrupt the connections between the VTA, amygdala, and NAc. This disruption decreases the amygdala’s effectiveness in supporting reward learning, leading to blunted reward sensitivity and anhedonia, common in mood disorders like depression [7]. Additionally, early stress exposure may cause the brain to revert to a more immature state, where neuromodulators like NE and 5-HT dominate reward processing. This shift can lead to over-engagement of these systems, resulting in less effective reward learning and diminished responsiveness to natural rewards, increasing susceptibility to maladaptive behaviors like substance use [2, 108]. Adversity also affects cellular plasticity, reducing synaptic flexibility in the VTA and NAc. This diminished plasticity impairs the formation of strong links between positive stimuli and behavior, making it harder for individuals exposed to early adversity to experience pleasure from typical rewards. This struggle may predispose them to depressive states or compulsive behaviors as compensatory mechanisms [109].

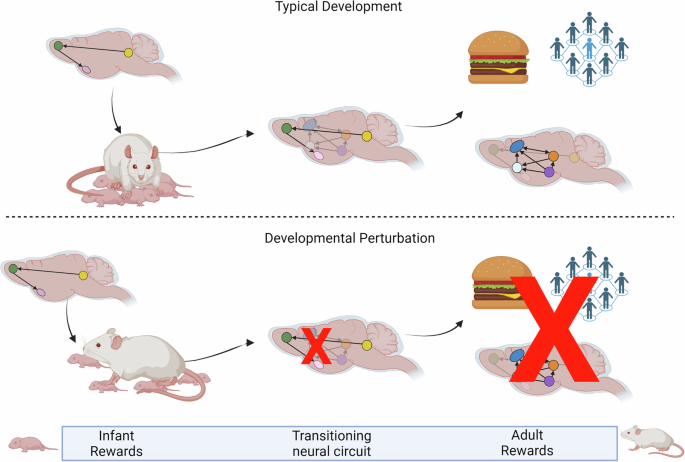

These models provide compelling evidence of immediate and lasting impacts of early adversity on brain regions important for adult reward. However, additional framing is needed to account for how adversity could program lasting changes to regions inactive at the time of adversity. In many cases it is believed that the temporal separation between structural and functional maturation to induce behavior is actually necessary to allow experience to fine-tune continued neurodevelopment [110,111,112]. A useful example for translating this concept into the framework of reward learning is the idea of species-expected input as necessary for healthy reward circuit development. In this model, early brain circuits promote developmentally-appropriate behavior, such as seeking the caregiver. The caregiver then provides the expected and necessary input to guide the healthy maturation of adult circuits, while also generating age-specific early life behaviors (Fig. 3). In contrast, early perturbations to infant circuitry disrupt normal infant behaviors and in a cascading effect, prevent the exposure to species-expected stimuli inputs necessary for healthy programming and scaffolding of maturing adult circuits. For example, adversity decreases the infant’s approach toward the caregiver through a mechanism involving DA-ergic innervation of the BLA at a time when the VTA-BLA is continuing to structurally and functionally develop ([74]. This perturbation to behavior then prevents acquisition of stimuli necessary for further maturation of reward circuits.

Throughout this review, we have highlighted evidence showing that distinct circuits may serve outwardly similar behavior in early life versus adulthood. However, if this is the case, how can external perturbations during development disrupt adult function? One possible paradigm may be that early circuits promote developmentally-specific acquisition of resources, such as the infant attachment circuitry promoting approach and attachment to a caregiver. This caregiver then provides resources, such as protection, warmth and food, but also species-expected social stimulation. All of these inputs may be necessary for healthy maturation of the adult reward circuitry. By contrast, species-atypical caregiver inputs can prevent the normal scaffolding and maturation of this circuitry.

In early life, structural plasticity enables activity patterns to concurrently evoke age-appropriate behavior and program the brain prior to its full engagement in output and behavior [113]. Using the framework of reward, we argue for the importance of experimentally dissociating activity from function using gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies (required for behavior) for distinguishing between activation (wave 2) and functional use in behavior (wave 3) (Fig. 1). This information is critical for designing and interpreting reward tasks in development, identifying emerging indicators of pathology, and overall understanding and conceptualizing brain development.

Conclusion

Here we have briefly reviewed the neural circuit mechanisms supporting early reward function in the infant/juvenile rat and human. In doing so, we have begun to address three critical questions posed to the field, though much more must be done in this area.

First, how is reward assessed in early life? In infancy, caregivers satisfy the three components of reward (wanting, liking, reinforcing), but this process does not rely upon the canonical, adult-defined, reward circuitry involving mesolimbic DA signaling. It is important to note that adult reward learning can occur without DA and in brain regions beyond the mesolimbic DA circuit. However, we have focused on a dichotomy between infant and adult mesolimbic DA signaling in reward based on the stark differences in DA function suggested by the literature on caregiver approach.

As infants transition to independence, the social reward function becomes more adult-like, involving mesolimbic circuit components. This assessment highlights our key argument, and an answer to the second critical question, that behavioral similarity across development does not imply circuit continuity. Together, these premises lead us to speculate how early experience may shape adult behavior despite anatomically distinct circuitry. Namely, developing reward systems may promote acquisition of species-expected input necessary for healthy maturation into adult brain circuits.

We further posit that different age-specific neurobehavioral patterns may reflect the environmental demands of the individual (e.g. form attachment to caregiver), neuroanatomical trajectories of development, or both. As an individual develops through childhood and into adolescence, recognizable features of the adult-defined reward system do emerge. Yet, such results must be taken with caution, as we emphasize a critical premise: similar activation of brain areas in infancy and adulthood may not reflect functional necessity of immature regions for behavior.

With these considerations in mind, the reader may be left with a new critical question: where do we go from here? Overall, data on early reward function suggest that the ecological niche of the developing individual is necessary to consider when designing and interpreting reward tasks, especially during infancy (Box 1). This information will be crucial in identifying developmentally-relevant points of entry for preventative strategies and therapeutic interventions in early life. More broadly, this framework may be needed for conceptually and theoretically approaching developmental research questions, including but also extending beyond the scope of reward.

Responses