Methods to address functional unblinding of raters in CNS trials

Introduction

Functional unblinding in double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials may occur when some inherent property of the investigational product (IP) generates side effects, known as treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), that distinguish the IP from placebo. When it occurs, functional unblinding may alter expectation biases and may amplify the treatment effect because clinician raters and/or trial participants believe they are receiving the IP regardless of the actual treatment assignment [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Of course, these beliefs may be mistaken because many side effects such as gastrointestinal discomfort, headache, or drowsiness come and go in participants assigned to placebo as well as IP and can occur in people who are not participating in any experiment at all. Therefore, concerns about functional unblinding are important for studies in which a distinctive side effect profile occurs more often in IP-assigned than placebo-assigned participants and may affect the integrity of the clinical assessments and, consequently, confidence in the trial results.

Subjective outcome measures are more likely to yield amplified treatment effects than objective measures when there is a lack of successful blinding [2,3,4, 10]. It is noteworthy that many of the items assessed by central nervous system (CNS) rating instruments are relatively subjective and require careful clinical judgment. Historically, it was difficult to truly blind first-generation antipsychotic medications (e.g., haloperidol), anxiolytics, or tricyclic antidepressants because of their distinctive side effects and the use of inert rather than active placebos [11,12,13]. Many of the more recently developed psychotropic medications have better safety profiles and less obvious side effects such that differences between IP and placebo may be less detectable [14]. However, some newer psychotropic medications can cause distinctive side effects that might differentiate them from placebo. For instance, esketamine infusions for treatment-resistant depression can induce dissociative reactions that might functionally unblind raters and participants during double-blind, placebo-controlled trials such that they can correctly guess who is receiving the IP [15,16,17,18].

Most CNS trials do not assess the possibility of functional blinding. In a systematic review of CNS trials of schizophrenia and mood disorders conducted between 2000 and 2010, only 61 of 2476 publications (2.5%) assessed blinding success by directly asking trial participants or raters about their beliefs regarding treatment group assignment [19]. In a recent meta-analysis of antidepressant studies between 2000 and 2020, only 11 of 154 studies (7.1%) contained information about blinding assessments [14]. In fact, clinical trials across the medical spectrum rarely investigate the possibility of effectiveness of the blinding design [4, 5, 9, 19,20,21,22]. Hróbjartsson et al. [9] reported that only 2.0% of 1599 clinical trials conducted across all areas of medicine assessed the success of blinding.

We have used complementary, alternative strategies to shed light on the issue of functional unblinding in clinical trials. One method has been to compare the scores obtained by remote (site-independent) raters who are blinded to medication assignment, visit number, rater, site, and any possible TEAEs with “paired” site-based scores of the same participant. Remote ratings review is often used as a quality assurance strategy to identify substandard site-based raters and to reinforce ratings precision [23, 24]; however, remote ratings can also be used to address the possibility of functional unblinding [15, 25]. For instance, in a small exploratory trial conducted at one clinical trial site, remote raters who were blinded to TEAEs scored audio-recordings of site-based Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale interviews and replicated the treatment response in 13 of 14 (92.9%) patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) receiving esketamine or placebo infusions [15]. To fully address and rule out the possibility of functional unblinding and facilitate comparison with site-based scores, this method requires obtaining remote ratings from all trial sites at both the baseline and endpoint interviews. In effect, the remote ratings are a type of “shadow” study with results that are blinded to TEAEs and are independent of the primary efficacy ratings administered by site-based clinicians.

A second method to address the possibility of functional unblinding in clinical trials is to conduct a post hoc analysis of treatment effects in trial participants who did or did not report specific IP-related TEAEs during the trial. This method of addressing functional unblinding is similar to the approach of Marder et al. [26] who suggested that functional unblinding had influenced the perceived treatment assignment and affected trial outcome in a placebo-controlled, active-reference (quetiapine extended release [XR]), 6-week trial of brexpiprazole. The active reference medication, quetiapine XR, did significantly better than placebo (p = 0.0002), whereas the IP, brexpiprazole, came close but failed to separate from placebo (p = 0.056). In a post hoc analysis, these investigators found that a subgroup of 16 participants out of the 150 assigned to brexpiprazole had experienced typical quetiapine XR-like TEAEs (e.g., somnolence) and had the numerically largest mean PANSS improvement from baseline than all other subgroups and a treatment response that was significantly better than placebo (p = 0.0057). The authors suggested that quetiapine XR-like TEAEs may have functionally unblinded the treatment assignment, amplified ratings of improvement, and positively influenced the efficacy ratings in this small subgroup [26]. This report highlights the valid concern that functional unblinding might influence ratings of improvement, obscure the interpretation of treatment outcome, and affect confidence about trial results.

For this report, we used both of these methods to assess the possibility of functional unblinding affecting clinical trial results in three recent studies of acute exacerbation of psychosis in schizophrenia with the medication xanomeline and trospium chloride (formerly known as KarXT; Karuna Therapeutics, Boston, Massachusetts, USA), approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in September 2024 for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults [27,28,29]. We used pooled data from these studies to examine a) the success of paired audio recorded PANSS interviews scored by remote raters blinded to TEAEs to replicate the site-based, live ratings and b) the relationship of the presence or absence of IP-specific TEAEs to treatment outcome using the post hoc analysis method described by Marder et al. [26]. Xanomeline/trospium is a recently approved antipsychotic medication that was developed as a broad-spectrum monotherapy for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults [27,28,29]. Xanomeline/trospium is a combination of xanomeline tartrate, a M1/M4 preferring central muscarinic receptor agonist, and trospium chloride, a peripherally restricted muscarinic receptor antagonist. Clinical studies of xanomeline have shown improvements in psychosis and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease and in positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia, though tolerability related to cholinergic side effects was a problem in the early studies [30,31,32]. Dose-dependent cholinergic adverse events were reported (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, sweating, and hypersalivation) that were likely mediated by stimulation of peripheral muscarinic cholinergic receptors [30, 31]. The novel combination of xanomeline with trospium, a peripheral anticholinergic agent, mostly blocks the peripheral adverse cholinergic effects of xanomeline while allowing its therapeutic antipsychotic effects [32, 33]. Nonetheless, some cholinergic adverse events may occur during treatment with xanomeline/trospium and possibly functionally unblind ratings. Therefore, xanomeline/trospium is a good IP candidate to investigate the possibility of functional unblinding affecting trial results.

Materials/participants and methods

Data for these post hoc analyses come from three separate 5-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that assessed the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of xanomeline/trospium in hospitalised adults with schizophrenia experiencing an acute exacerbation of psychosis. The three studies, EMERGENT-1, EMERGENT-2, and EMERGENT-3 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT3697252, NCT04659161, NCT04738123), were sponsored by Karuna Therapeutics and were conducted sequentially between September 2018 and May 2022 at study centers in the United States. EMERGENT-3 included trial sites in Ukraine as well. A full description of the methods and results of these three studies has been reported previously [27,28,29].

Eligible participants were men or women between the ages of 18 and 65 years (upper age 60 years in EMERGENT-1) who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, criteria for schizophrenia confirmed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview and presented with an acute exacerbation of psychosis or a relapse of symptoms with an onset fewer than two months before the screening visit [27, 29, 34]. The inclusion criteria required a PANSS total score between 80 and 120 (inclusive), a score of at least 4 on at least two of four key positive symptom items (delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, suspiciousness), and a Clinical Global Impression of Severity score of at least 4 at the screening and baseline visits [35, 36].

In all three studies, enrolled participants were randomised to either oral xanomeline/trospium or placebo in a 1:1 ratio for a treatment period of five weeks. Xanomeline/trospium was titrated to a maximum dose of xanomeline 125 mg/trospium 30 mg twice daily (BID). Flexible dosing was employed to maximise therapeutic benefit while avoiding intolerable adverse events. Dosing began with a lead-in dose of xanomeline 50 mg with trospium 20 mg BID for the first two days followed by xanomeline 100 mg/trospium 20 mg BID for the remainder of week 1 (days 3 to 7) and titrated upwards on day 8 to xanomeline 125 mg/trospium 30 mg BID, unless the participant was continuing to experience adverse events from the previous dose increase.

Ethics statement

All three studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice as outlined by the International Conference on Harmonization. The trial protocols and consent forms for all three trials were reviewed and approved by independent ethics committees and centralized institutional review boards (EMERGENT-1: Copernicus Group, Cary, NC, tracking number 420180321; EMERGENT-2: WCG IRB, Puyallup, WA, tracking number 20203606; EMERGENT-3: WCG IRB, Puyallup, WA, tracking number 20204339); written informed consent was obtained from all participants before any protocol-specified procedures or interventions were performed. All participants consented to trial participation and to audio recording of interviews by independent raters (described below).

Obtaining paired ratings from audio-recordings of site-based PANSS interviews

We compared paired remote ratings of the PANSS total score with site-based scores. PANSS interviews were administered by trained site-based raters using the Structured Clinical Interview for the assessment of PANSS (Multi-Health Systems Inc., Toronto, Canada). Every PANSS interview at every trial visit (screening, baseline, and weekly in-trial assessments throughout the 5-week trial) was audio-digitally recorded and electronically transmitted to Signant Health (Boston, Massachusetts, USA) for quality assurance review. In each trial, PANSS ratings were obtained from remote raters who reviewed digital notes that contained corroborative informant information and listened to and scored audio recordings of the site-based PANSS interviews [25]. The remote raters were blinded to the trial site, trial visit, or any possible TEAEs. Lacking direct visual observation, four PANSS items that required direct observation of participant behaviour during the interview, N1 (blunted affect), G4 (tension), G5 (mannerisms and posturing), and G7 (motor retardation), were carried over from the site-based score to generate the remote PANSS total score.

Identification of TEAEs

TEAEs were categorised by type and summarised by treatment group in all three studies. An adverse event was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a clinical trial participant and could therefore be any unfavourable and unintended sign, symptom, or disease temporally associated with the use of xanomeline/trospium or placebo whether it was related to the IP or not.

The post hoc subgroup-based analyses of the relationship of TEAEs to treatment outcome examined all reported TEAEs as well as the specific cholinergic adverse events that might be construed as being related to xanomeline/trospium. The consent forms from each of these studies noted that the investigational trial medication might cause unpleasant side effects or reactions and noted many cholinergic side effects. In this analysis, we included the cholinergic-related side effects that followed Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities guidelines, which that included nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, indigestion (dyspepsia), gastroesophageal reflux, constipation, hyperhidrosis, hypohidrosis, salivary hypersecretion, lacrimation, dry mouth, urinary retention, excess sweating, miosis, blurred vision, tachycardia, fainting, dizziness, somnolence, hypotension, lightheadedness, and worsening of narrow-angle glaucoma.

Statistical methods

The analyses of paired remote ratings and TEAEs related to treatment outcome used the modified intention-to-treat population (mITT) from each trial, which was defined as all randomised participants who received at least one dose of trial medication, had a baseline PANSS assessment, and had at least one postbaseline PANSS assessment.

Comparison of paired site-based vs remote ratings

The comparative analysis between paired site-based and remote PANSS ratings focused on the baseline and endpoint (or early termination) visits in all studies. First, the correspondence between site-based and remote ratings was evaluated by computing intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) between the paired ratings at the baseline and endpoint assessments. Second, xanomeline/trospium treatment effects were evaluated for site-based and remote PANSS total scores using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model on change from baseline to endpoint at week 5 in the PANSS total score, adjusting for baseline PANSS total, treatment group (xanomeline/trospium or placebo), rater type (site-based or remote), study, age, and sex, and the interaction between treatment group and rater type. In addition, we conducted ICC and ANCOVA analyses with 26 PANSS items after omitting the 4 PANSS items that require observation and were carried over to the site-independent ratings. Third, a responder analysis used a 30% or greater improvement of the PANSS total score from baseline to endpoint as the criterion for treatment response. The calculation subtracted 30 points from the baseline PANSS score to account for PANSS scaling from 1 to 7 on each of the 30 items rather than 0 to 6 [37, 38].

Comparison of TEAE-based subgroups

We assessed the correspondence between site-based and remote ratings on PANSS total scores and compared xanomeline/trospium treatment effects for the site-based and remote PANSS total scores within four TEAE-defined subgroups of interest: trial participants who reported cholinergic-related TEAEs that might be related to the trial medication (xanomeline/trospium-specific TEAEs), trial participants who reported no cholinergic-related TEAEs that might be related to the trial medication, trial participants who reported any TEAEs at all during the trial, and trial participants who reported no TEAEs at all during the trial.

First, we examined the ICC between the site-based and remote scores at baseline and endpoint within each of the subgroups. Second, we evaluated treatment effects within each of the subgroups. For site-based ratings, the difference between xanomeline/trospium and placebo change from baseline to endpoint was estimated using a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) on change from baseline in the PANSS total score. Fixed factors included treatment group (xanomeline/trospium or placebo), visit, study, and sex and the interaction between treatment group and visit. Baseline PANSS total score and age were covariates in the model. An unstructured covariance matrix and a random subject intercept were used to model the covariance of within-subject scores.

The remote ratings analyses used only the baseline and endpoint visit data. Therefore, an ANCOVA model for the change from baseline was used to explore treatment group difference at endpoint, adjusting for baseline PANSS total, study, sex, and age.

The least squares (LS) mean change from baseline, standard error (SE), and LS mean difference between xanomeline/trospium and placebo at endpoint, along with the 95% confidence interval and two-sided p-value for the hypothesis testing are presented from both the MMRM (site-based ratings) and ANCOVA (remote ratings) models. Effect size, where presented, is estimated by Cohen’s d and calculated from the model statistics using the LS mean differences and pooled standard deviations. All statistical tests are two-sided with α = 0.05 and multiple comparison techniques were not employed. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows, Release 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and IBM SPSS for Windows, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

The objective of these analyses was to assess the role, if any, of functional unblinding on trial outcome. A more complete description of the efficacy and safety results from these studies has been reported elsewhere [27,28,29]. We combined data from the three separate studies for this analysis.

Comparison of paired site-based and remote PANSS ratings

Data for the comparative paired analyses included participants who had clinician site-based and remote PANSS ratings at both the baseline and endpoint (or early termination) visit in each trial. Acceptable data were available for 575 participants, accounting for more than 95% of enrolled participants. There were 286 participants assigned to xanomeline/trospium and 289 assigned to placebo.

The ICCs between the 575 paired site-based and remote PANSS total scores were high at the baseline and endpoint visits (ICCs = 0.88 and 0.93 respectively; both p < 0.001). We analyzed the ICC using 26 of the 30 PANSS items without the 4 items that were carried over to the remote ratings (N1, G4, G5, and G7). Although slightly less robust, the ICC between site and remote raters for the PANSS 26 was r = 0.75 at baseline and r = 0.85 at study endpoint (both p < 0.001).

Table 1 reveals the trial results comparing the paired site-based and remote PANSS total scores for xanomeline/trospium versus placebo for the three pooled studies. The remote raters who had no knowledge of possible TEAEs essentially replicated the site-based PANSS total score results. Both site-based and remote ratings yielded significant findings favouring xanomeline/trospium-assigned participants over placebo-assigned participants on the PANSS total (both p < 0.0001). Additionally, there is no evidence to suggest that the strength of the xanomeline/trospium effect significantly differed between site-based and remote raters (treatment × rater-type interaction p = 0.172). The results did not change when we analyzed the PANSS scores using the 26 PANSS items without the 4 items that were carried over. The xanomeline/trospium treatment group was still significantly better than the placebo group for site-based ratings (ANCOVA: F = 55.8; p < 0.0001) and site-independent (remote) ratings (F = 28.3; p < 0.0001).

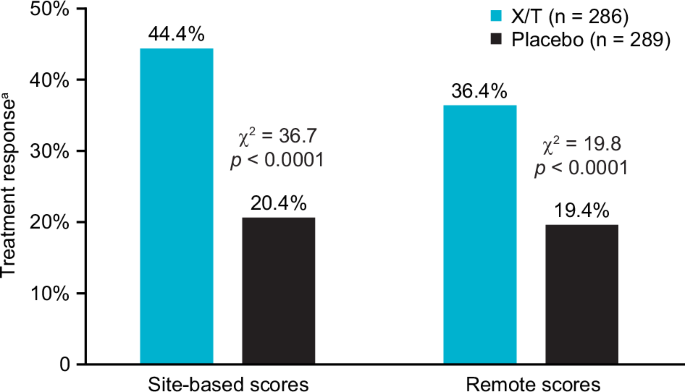

Figure 1 depicts the treatment response (≥30% PANSS total score improvement from baseline) for the combined studies. Both site-based and remote ratings yielded significantly greater treatment response for xanomeline/trospium-assigned participants than placebo-assigned participants. There were 127 xanomeline/trospium responders (44.4%) in contrast with 59 placebo responders (20.4%) based upon the site-based PANSS total scores (χ2 = 36.7; df = 1; p < 0.0001) and 104 xanomeline/trospium responders (36.4%) in contrast with 56 placebo responders (19.4%) based upon the remote PANSS total scores (χ2 = 19.8; df = 1; p < 0.0001). The proportion of participants that improved on xanomeline/trospium did not differ significantly between the site-based (68%) and site-independent (65%) ratings, (χ2 (1, N = 346) = 0.42, p = 0.52). The overall total predictive value of remote scores matching the site-based treatment response outcome for the combined three studies was 88.0%.

aTreatment response defined as ≥ 30% improvement from baseline to endpoint of the PANSS total score. PANSS Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, X/T xanomeline/trospium.

Reported TEAEs

In the full combined safety population from the three pooled studies (n = 683), 407 participants (59.6%) reported at least one TEAE of any kind. In the safety population, 68% of xanomeline/trospium-assigned participants and 51% of placebo-assigned participants experienced at least one TEAE at some point during these trials.

Table 2 lists the most frequently reported TEAEs in the safety populations of these three combined trials. The most common cholinergic TEAEs reported were nausea, constipation, dyspepsia, and vomiting. These commonly reported cholinergic TEAEs generally began within the first two weeks of treatment and were transient mild to moderate symptoms that did not result in trial withdrawal. The median number of days on treatment for these TEAEs were (xanomeline/trospium|placebo): nausea (8.5|2.0), constipation (9.0|5.0), dyspepsia (14.0|11.0), and vomiting (2.5|13.0). All vomiting TEAEs were intermittent, with a single episode of emesis reported in approximately one-third of the reported cases. Xanomeline/trospium was not associated with typical antipsychotic side effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms, somnolence, or weight gain. A full description of TEAEs that occurred in each these studies separately has been reported elsewhere [27,28,29].

We assessed the relationship of TEAEs to trial outcome in the mITT population by comparing the subgroups that were categorised based upon the presence or absence of TEAEs during the trial as described in the methods. For the site-based ratings analyses, we used data from the 586 participants in the mITT population. For the paired ratings analyses, we used data from the 575 participants in the mITT population who had both site-based and remote ratings at baseline and endpoint.

Correlation between site-based and remote PANSS scores based upon the presence or absence of TEAEs

Within the sample of participants with available paired site-based and remote ratings (n = 575), there were 213 reported cholinergic-related TEAEs (37.0%) and 348 reported TEAEs of any kind (60.5%) during the trial (Table 3). There was no difference in the ICC found at either the baseline or endpoint visits between the site-based and remote PANSS total scores based upon the presence or absence of reported cholinergic-related TEAEs, or any TEAEs at all. The ICC ranged between 0.86 and 0.94 (p < 0.001 in all cases).

Relationship of TEAEs to trial outcome by site-based PANSS ratings

As shown in Table 4, for participants with site-based ratings (n = 586), there was no relationship found between the significant improvement of PANSS total scores favouring xanomeline/trospium over placebo and the presence or absence of cholinergic-related TEAEs, or any TEAEs at all (all analyses p < 0.001). Cohen’s d effect size analyses for the PANSS total favoured xanomeline/trospium over placebo at similar magnitudes in the mITT population (d = 0.65), the subgroup of 213 participants who reported cholinergic-related TEAEs (d = 0.58), the subgroup of 373 participants who reported no cholinergic TEAEs (d = 0.55), and the subgroup of 242 participants who reported no TEAEs at all (d = 0.67). An additional analysis that omitted that 4 PANSS items that were carried over to the remote scores found similar effect sizes (Supplementary Table 2).

The LS mean difference favouring xanomeline/trospium over placebo was −8.6 ± 2.37 (SE) in the subgroup who reported cholinergic-related TEAEs and −8.3. ± 1.69 in the subgroup who reported no cholinergic-related TEAEs (both p < 0.001). Hence, the presence or absence of reported cholinergic-related TEAES during the trial did not affect the magnitude of the finding that xanomeline/trospium was significantly better than placebo.

In a secondary analysis, we examined the relationship of the time of occurrence of cholinergic-related TEAEs to trial outcome. In the pooled sample of three trials in the mITT population, 174 of the 213 participants who reported cholinergic-related TEAEs (81.7%) experienced the events within the first two weeks of double-blind treatment. The presence or absence of cholinergic-related TEAEs within the first two weeks did not affect the site-based PANSS trial results. Among the participants who reported early cholinergic-related TEAEs, the xanomeline/trospium-assigned participants did significantly better than placebo-assigned participants (LS mean difference = −8.1 ± 2.70 [SE]; p = 0.003; d = 0.53) as did participants who did not report early cholinergic-related TEAEs (LS mean difference = −8.7 ± 1.56; p < 0.001; d = 0.59). Additional findings related to the timing of occurrence of TEAEs are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Relationship of TEAEs to trial outcome by remote PANSS ratings

For participants with both site-based and remote ratings (n = 575), there were 213 reported TEAEs categorized as cholinergic-related TEAES (37.0%). As shown in Table 5, there was no relationship found between the significant improvement of PANSS total scores favouring xanomeline/trospium-assigned participants over placebo and the presence or absence of cholinergic-related TEAEs, or any TEAEs at all. Cohen’s d effect size analyses for the remotely rated PANSS total scores favoured xanomeline/trospium over placebo and were at similar magnitudes in the mITT population (d = 0.44), the subgroup of 213 participants who reported cholinergic-related TEAEs (d = 0.47), the subgroup of 362 participants who reported no cholinergic TEAEs (d = 0.38), and the subgroup of 227 participants who reported no TEAEs at all (d = 0.44). An additional sensitivity analysis that omitted the 4 PANSS items that were carried over to the remote scores found slightly lower but similar effect sizes (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

We used two different methods to address the possibility of functional unblinding in three successful studies of xanomeline/trospium versus placebo in participants with schizophrenia who were experiencing an acute exacerbation of psychosis. In the first method, we assessed whether PANSS total scores derived by remote raters listening to audio recordings of site-based PANSS interviews and blinded to any possible TEAEs could replicate the paired site-based scores. In the second method, we analyzed the PANSS total score for four subgroups based upon reports of any TEAEs, reports of cholinergic-related TEAEs that might be related to the known side effects of xanomeline/trospium, reports of no cholinergic-related TEAEs, or no reported TEAEs at all. The results from both methods of analysis revealed that the presence or absence of cholinergic side effects, or any TEAEs at all, did not affect the results of these studies.

As expected by the mechanism of action of xanomeline/trospium, the most reported TEAEs during the trial were cholinergic-related events such as constipation, dyspepsia, nausea, and vomiting. These TEAEs occurred more often in participants receiving xanomeline/trospium than placebo and were mild to moderate and generally transient in nature. Nonetheless, the post hoc TEAE analysis revealed a significantly greater improvement of the PANSS total score in xanomeline/trospium-assigned participants than placebo-assigned participants whether they reported these cholinergic-related TEAEs, any TEAEs, or no TEAEs at all during the trial (all groups were p < 0.001). Thus, the presence or absence of cholinergic-related side effects occurring during the trial had little to no impact on trial results.

The remote raters, who were blinded to study site, study visit, and any possible TEAEs because they had no visual observation of the participants or TEAE information, essentially replicated the PANSS scores of the site-based raters. Both site-based and remote ratings favoured xanomeline/trospium-assigned participants over placebo on the PANSS total after five weeks of treatment (p < 0.0001). The remote raters achieved high predictive value (88.0%) for matching the significant treatment response outcomes of the site-based raters. The ICC between the site-based and remote PANSS scores at either baseline or endpoint visits ranged between 0.87 and 0.94 (p < 0.001) regardless of the presence or absence of cholinergic-related TEAEs, or any TEAEs at all. Further, a post hoc analysis of reported TEAEs in both the site-based and remote ratings population affirmed that participants assigned to xanomeline/trospium did significantly better than placebo-assigned participants whether they reported cholinergic-related TEAEs, any TEAEs, or no TEAEs at all during the trial. Thus, the replication of trial results by the remote blinded raters using both methods of assessment affirms that any awareness of cholinergic-related TEAEs by the live site-based raters had little or no impact on the trial results obtained.

Our findings that reported TEAEs did not affect trial results differ from those of Marder et al. [26]. These authors believed that the sedating properties of quetiapine XR may have functionally unblinded some raters and influenced their ratings in a schizophrenia trial in which brexpiprazole (N = 150) did not separate from placebo on the primary measure, the PANSS total score [26]. In a post hoc analysis, these investigators found that brexpiprazole was significantly better than placebo on the PANSS total score in a very small subgroup of participants (n = 16) who were treated with brexpiprazole but had experienced quetiapine-like TEAEs. Of course, functional unblinding may or may not have had a role in distinguishing this small subgroup. The sedation associated with quetiapine-XR may have abetted symptoms such as anxiety and agitation that are often associated with acute psychosis and contributed to the clinical improvement regardless of functional unblinding. As with most CNS studies, these authors did not query raters or participants about their guess regarding treatment allocation. Without queries of raters or participants, it is impossible to untangle the confounding possibility that a therapeutic benefit may have accrued from the known side effect regardless of functional unblinding.

Although our findings reveal that there was no discernible effect of functional unblinding in these studies, we cannot assert that functional unblinding did not occur at all. It is possible that blinding was successful or that any unblinding that did take place due to TEAEs did not appreciably impact the outcome for PANSS-based ratings.

A limitation of the two methods described in these analyses is that we addressed functional unblinding of raters but did not consider the perspective or expectations of the participant. It is possible that any perception about treatment allocation, whether it is right or wrong, can bias a participant’s response to treatment [1]. For instance, it has been shown that the participant’s awareness of two or more active treatment arms versus placebo can amplify the placebo response in contrast to 1:1 treatment allocation [39]. Alternatively, TEAEs might not influence participant perspective or affect treatment response at all [13, 14]. Trial participants are directly informed about the possible side effects associated with the IP when they read and sign an informed consent form [40]. In practice, few participants re-read the informed consent to remind themselves about IP-related side effects after a trial begins. Instead, participants may presume that any TEAE (e.g., headaches, drowsiness, dyspepsia) experienced during a trial is associated with the IP. The belief that one is taking the trial medication because of a TEAE may amplify the treatment response regardless of treatment allocation. Alternatively, the absence of any TEAE may lead some participants to believe that they are not taking the IP and this perspective may or may not contribute to a nocebo effect. Thus, the participant’s perspective on treatment allocation may or may not influence the treatment response.

As in most clinical trials, we did not query the participants or raters about their guess about medication assignment in these three xanomeline/trospium studies. In fact, participants are rarely asked to guess their treatment assignment [14, 19, 41]. In a review of CNS trials of schizophrenia or mood disorders conducted in the decade between 2000 and 2010, Baethge et al. [19] reported that only 2.5% of 2476 publications reported assessing participant, rater, or clinician blinding. In their analyses, the proportion of participants’ and raters’ correct guesses of trial arm averaged 54.4 and 62.0%, respectively. A recent meta-analysis by Scott et al. [41] of randomised trials of antidepressants for MDD reported that only 4.7% of 295 trials assessed the success of blinding. Similarly, another meta-analysis by Lin et al. [14] found that fewer than 10% of antidepressant randomised clinical trials reported blinding assessment. From nine trials with usable data, these authors reported that trial participants and raters were unlikely to guess their treatment assignment for the new generation of antidepressants and that there was little evidence that functional unblinding biased the effect size estimates of the clinical trials [14]. These findings differ from studies with esketamine or ketamine for which raters and participants can often correctly guess treatment assignment [16, 17].

An interpretation about the specific impact of functional unblinding on trial results is not straightforward and is confounded by several factors. For instance, the expectation of receiving an active treatment prior to entering a clinical trial may enhance the perceived efficacy of any treatment. It has been shown that a participant’s awareness of more than one active treatment arm in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial can amplify the placebo response over 1:1 treatment allocation [39]. Further, clinical improvement during the trial regardless of treatment assignment may lead trial participants to believe they are receiving active treatment. Rickels et al. [11] asserted that clinical improvement or lack of response during a trial facilitated reliable medication guesses to break the blind more often than TEAEs [11]. In a 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in MDD, participants who believed they were taking active medication midway through the trial had significantly higher improvement in depressive symptoms at the endpoint than participants who believed they were taking placebo, regardless of TEAEs [42]. Alternatively, TEAEs may adversely affect general well-being, deflate the treatment response, and confound the ratings and interpretation of trial results [13, 43]. Thus, expectation biases upon entering a clinical trial, perceived response during the trial regardless of treatment assignment, and TEAEs may all affect and confound the interpretation of trial results. Although many recently approved CNS medications have minimal side effects, some medications such as esketamine or psychodelics possess unique side effect characteristics that could easily unblind their use within a short time [17]. Hence, it makes sense to attempt to minimise functional unblinding and to assess its presence in some studies.

In sum, both methods of analysis used to address the possibility of functional unblinding in these studies of xanomeline/trospium in schizophrenia revealed that the presence or absence of cholinergic side effects, or any TEAEs at all, did not impact the trial results. As shown, the post hoc analysis of the relationship of IP-related TEAEs to outcome is a useful method to assess potential functional unblinding effects on trial results. Similarly, the use of remote raters who are blinded to any knowledge of TEAEs is another useful, complementary method to address functional unblinding of site-based raters. These two methods address functional unblinding of ratings but do not resolve the issue of a participant’s perspective on treatment assignment. There is still a need to assess the views of raters and participants about treatment assignment and to explore the role of perception on treatment outcome. Additional studies about the role of functional unblinding on the amplification or deflation of true medication effects is warranted.

Responses