Impact of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for benign and malignant haematologic and non-haematologic disorders on fertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a potentially curative or consolidative therapy which is widely used in patients with either malignant and benign disorders (Snowden et al. [1]; Saad et al. [2]). The most common indications for HSCT include haematological diseases (e.g., haematological malignancies such as leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma) and haematological non-malignancies (e.g., aplastic anemia, thalassemia and Fanconi’s anemia), among other diseases [3, 4].

Due to the continuous expansion of HSCT indications, the number of HSCT continues to increase. In Europe in 2021, 47,412 HSCT were performed in 43,109 patients (19,806 (42%) allogeneic and 27,606 (58%) autologous). Simultaneously, 5-year survival rates after HSCT have improved, reaching 90% for some diseases [4, 5]. Consequently, there is increased awareness of various long-term complications such as infertility in patients receiving these highly effective therapies with high long-term survival. Previous reports show that the pregnancy rate after HSCT is less than 5% [6].

The knowledge regarding the toxicity of cancer treatments is expanding. Furthermore, treatment protocols are undergoing a transformation, resulting in enhanced outcomes, elevated survival rates, and a reduction in irreversible side effects. Given the high risk of primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) or testicular failure following HSCT conditioning and the negative impact of POI on fertility, it is imperative to consider protection of patients’ fertility prior to commencing HSCT.

Consequently, counselling about fertility preservation measures before the start of gonadotoxic therapies is crucial. However, fertility preservation in the context of diseases requiring HSTC is complex. For benign diseases in which HSTC is not urgently required or in which patients have not been pretreated with some kind of gonadotoxic therapies within a few month before the start of HSTC, all kind of fertility preservation measures such as freezing of oocytes, ovarian tissue, sperm and testicular tissue are feasible options. Conversely, in malignant diseases such as leukemia the situation is more complex. In males sperm can be frozen just before the start of the induction chemotherapy but in females time to freeze oocytes is too short. In some cases freezing of ovarian tissue can still be performed after induction chemotherapy and before HSTC has started if blood is free of leukemia cells. The situation becomes even more complex in case of prepubertal females and males in which only cryopreservation of ovarian and testicular tissue are feasible but experimental options in prepubertal cases [7,8,9].

Given the complexity of fertility preservation in patients definitely or possibly requiring HSTC, it is crucial to assess the expected and the potential risk of infertility before the onset of gonadotoxic therapies.

We therefore aimed to systematically assess the gonadal toxicity of myoablative treatments in both females and male patients with benign and malignant diseases. The study is part of the FertiTOX project (www.fertitox.com), which aims to close the data gap regarding the gonadotoxicity of anticancer therapies to provide more accurate advice about fertility preservation measures [10,11,12,13,14]. The intention of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to provide better guidance for oncologists and reproductive physicians regarding the risk of infertility and the necessity to consider fertility preservation measures. Even though HSTC treatments are heterogeneous which makes it difficult summarize these therapies, an overall estimation of the gonadotoxicity is urgently needed.

Materials and methods

Registration of protocols

This study protocol was registered in the Prospective International Registry of Systematic Reviews, (PROSPERO; registry number: CRD42023486928). The Preferred Reporting Criteria for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) were applied [15].

Search strategy

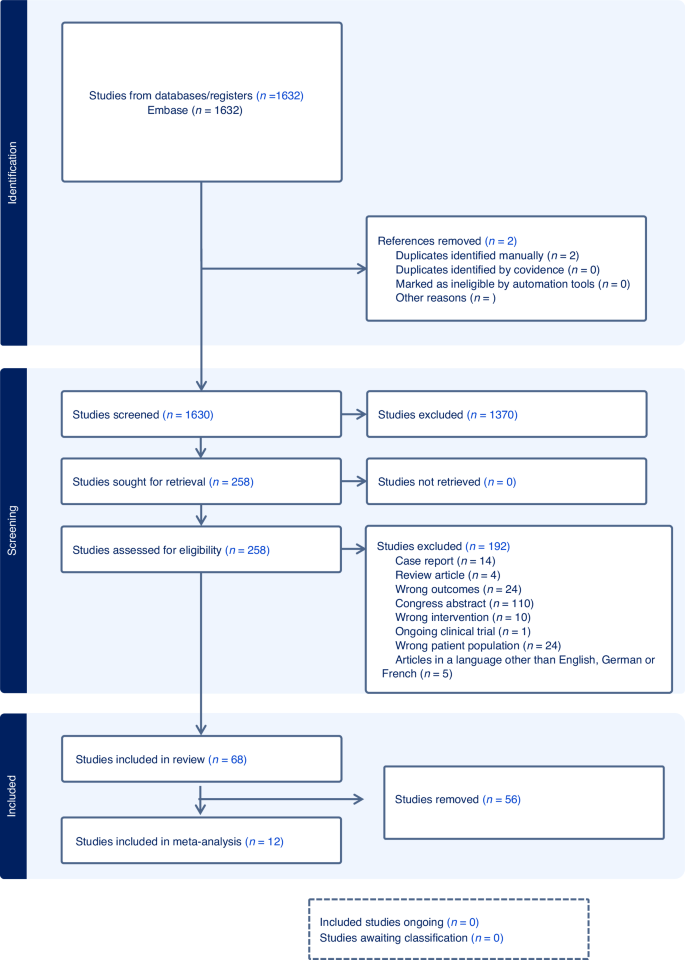

We conducted a systematic literature search of the Medline, Embase, and Cochrane CENTRAL databases in November 2023 (Fig. 1). An initial MEDLINE search strategy was developed by a medical information specialist and tested using a list of basic references. After refining and querying, complex search strategies were established for each information source based on database-specific controlled vocabulary (i.e., thesaurus terms/subject headings) and text words. The text word search included synonyms, acronyms and similar terms. We limited our search to publications from 2000 to the present. Our search terms included all types of cancers for both benign and malignant haematologic diseases.

Flowchart of the literature search and selection process.

Animal-only studies were excluded from MEDLINE and Embase searches using a double- negative search strategy based on Ovid “humans-only” filters. Detailed final search strategies are presented in a supplementary file (S1). Reference lists and bibliographies of relevant publications were reviewed for relevant studies in addition to searching electronic databases. All of the identified citations were imported into Covidence. Duplicates entries were removed [16].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two investigators (AV and CB) independently assessed studies for inclusion using the Covidence software (www.covidence.org) [17]. All original papers with information on the type of haematologic disease, tumor therapy and fertility outcomes with numbers that allowed calculation of prevalence were eligible. The definitions of clinically relevant gonadal toxicity are described in Table 1. Studies that did not evaluate gonadal toxicity as defined in Table 1 were excluded.

Data extraction

Two investigators (AV and CB) summarized and independently reviewed the extracted data in detail (Tables 2, 3). The key variables of interest included the characteristics of the study populations (patient age at diagnosis and outcome; duration of follow-up, benign and malignant haematologic diseases, tumor class, type of oncological treatment, and fertility parameters).

Quality assessment

The quality of individual studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [18]. The three parameters subject selection (0-4 stars), comparability (0-2 stars), and study outcome (0–3 stars) were considered in the scoring of individual studies. The scoring was composed as follows: good quality (= 3 or 4 stars in the selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in the comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in the outcome/exposure domain), fair quality (= 2 stars in the selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in the comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in the outcome/exposure domain), and poor quality (= 0 or 1 star in the selection domain OR 0 stars in the comparability domain OR 0 or 1 stars in the outcome/exposure domain). All of the included studies were reviewed by the AV and the CB to independently assess the risk of bias; disagreements were resolved via consensus. The scoring was conducted according to the terms listed in Table 4.

Data synthesis

The primary outcome of our systematic review was the prevalence of infertility in men and women with malignant or benign haematologic diseases after HSCT treatment. In order to calculate the prevalence, the number of patients who met the criteria for infertility was divided by the number of patients at risk of infertility, as provided by the individual studies. For the pooled prevalence, statistical analyses were performed with the “metafor” function of the R software (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria, 2013). Heterogeneity was examined using Cohen’s Q statistic and the I statistic [2]. In the presence of high heterogeneity, random-effects models were used. To provide clinically meaningful estimates in the meta-analysis, studies with unspecified treatments or < 10 patients were excluded for outcome assessment. However, they were included in the qualitative synthesis and tabular summaries of study characteristics (Table 2).

Results

Results of the systematic review

A total of 258 studies were included after screening of the abstracts and full texts. 192 studies were excluded because they did not meet the prespecified inclusion criteria. Finally, 68 articles were included in the systematic review (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 68 studies are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. The included studies were retrospective (n = 57), prospective (n = 6), and cross-sectional (n = 5). With the exception of five good-quality articles, the majority (n = 63) were rated as being of poor methodological quality. This was mainly due to the lack of a comparison group or small sample sizes (Tables 2 and 3).

A total of 4315 patients reported a history of benign/malignant haematologic disease and underwent HSCT, of which 2139 (49.5%) women and 2176 (50.4%) men were eligible for fertility analysis. Study sample sizes ranged from 5 to 217 patients. The studies were conducted in various regions, including Europe (n = 39), Asia (n = 18), the U.S. (n = 7), Canada (n = 3) and Australia (n = 1).

Benign haematologic diseases included Fanconi Anemia (FA), sickle cell disease (SCD), severe aplastic anemia (SAA), beta-thalassemia major (β-TM), congenital immunodeficiencies (CID), adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), Blackfan Diamond anemia, Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome, Glanzmann Syndome, X‐linked lymphoproliferative disease and others (OT). The histology of malignant haematologic diseases included chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL), myelodysplastic syndrome/myelofibrosis (MDS), multiple myeloma (MM), acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), acute unclassified leukemia (AUL), blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), Wilms tumour (WT), juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML), neuroblastoma, nephroblastoma, hepatoblastoma, neuroepithelioma, Ewing sarcoma and others (OT), including rare entities.

Study participants comprised of both prepubertal and post-pubertal males and females, with a median age of 10.8 years (range 0–66) at the time of cancer diagnosis and 22 years (range 1.1–62.4) at the time of outcome evaluation. The studies generally had follow-up periods, with a median of 7.2 years and a range of 0.2–31.3 years. Treatment options included various chemotherapy conditioning protocols with stem cell transplantation and/or different doses and types of radiotherapy. The exact proportion of patients with each specific type of treatment could not be determined.

Prevalence of infertility

The prevalence of infertility in patients with a history of HSCT ranged from 15% to 100% in women, and from 0% to 100% in men. Retrospective studies of long-term survivors [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] (mean follow-up 11 years) with reported infertility prevalence at 61% and 51%, respectively.

Results of the meta-analysis

Twelve studies that assessed fertility outcomes in fewer than 10 patients ([25, 32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]) were excluded to provide clinically meaningful estimates (Fig. 1).

Pooled overall prevalence of infertility after all types of treatment

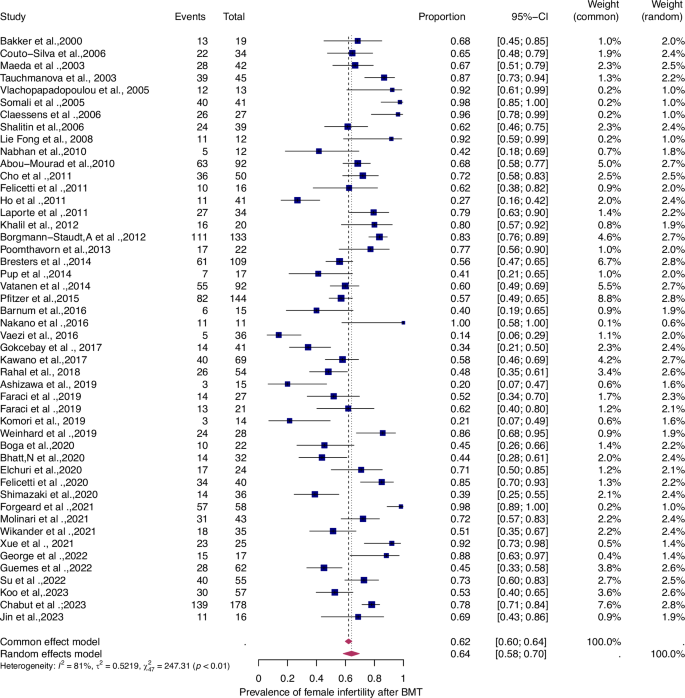

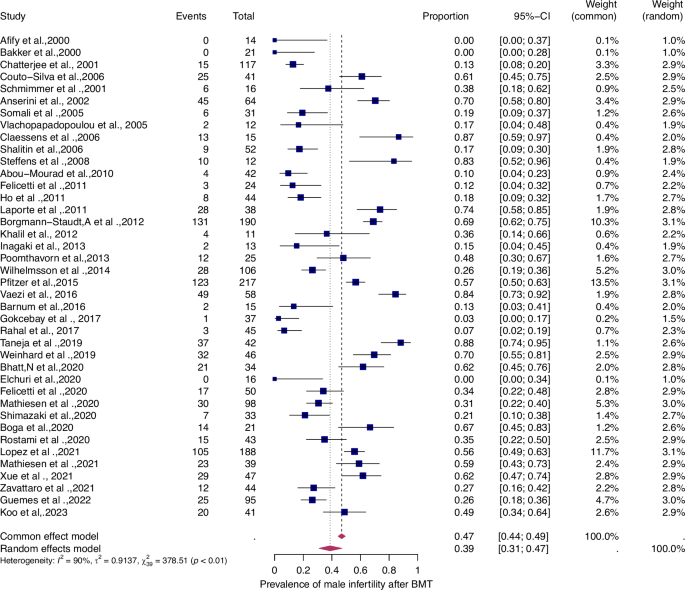

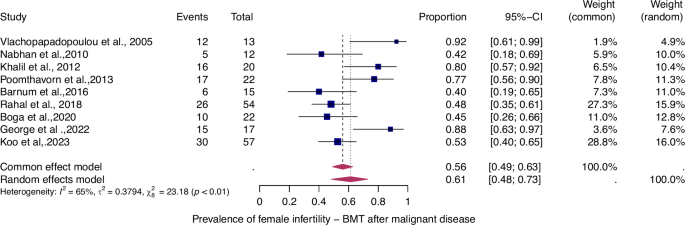

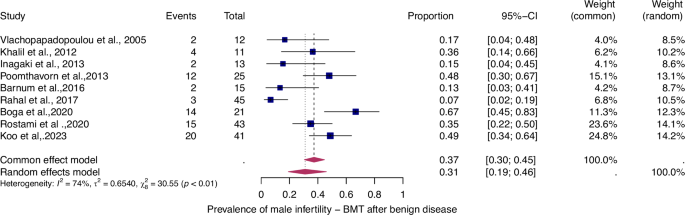

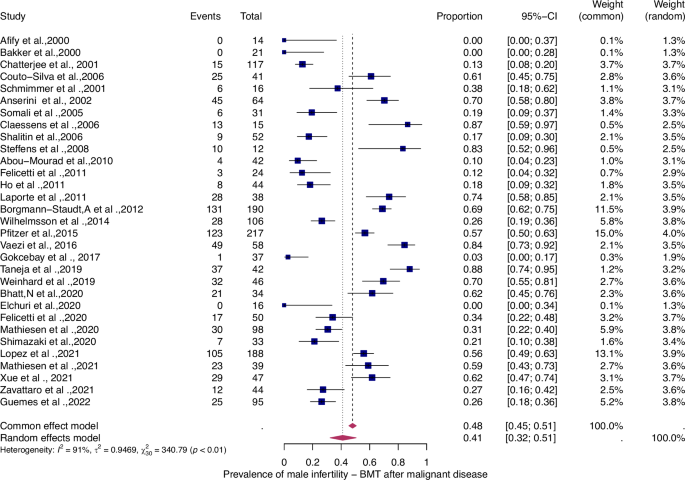

Fifty-six studies were eligible for inclusion in the analysis of the overall prevalence of infertility. These studies comprised 1853 female malignant cases, 241 female benign cases, 1871 male malignant cases, and 226 male benign cases. Consequently, patients were categorized according to their haematological disease, gender, and oncological therapy (i.e. different types and doses of chemotherapy and radiotherapy and combinations of different therapies). The prevalence of each of these studies and a summary of the prevalence are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. The overall prevalence was 64% (95% CI: 58-70%) for women and 39% (31-47%) for men. The heterogeneity test revealed significant heterogeneity among the studies I2 = 81, p < 0.01 and I2 = 90, p < 0.01.

Forest plot of proportions and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for studies evaluating the prevalence of gonadal toxicity in women following HSCT therapy. Blue squares for each study indicate the proportion, the size of the boxes indicates the weight of the study, and the horizontal lines indicate the 95% CI. The data in bold and pink diamond represent the pooled prevalence for post-treatment infertility and 95% CI. Overall estimates are shown in the fixed- and random effect models.

For details see legend of Fig. 2.

Subgroup analysis: Infertility in patients on the basis of disease type

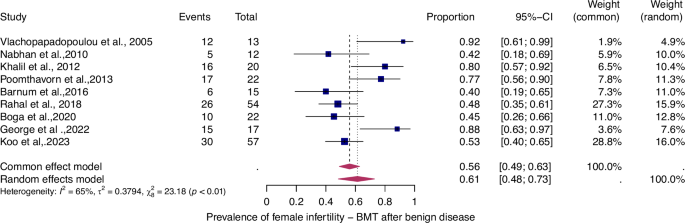

To evaluate the prevalence of infertility as a function of the type of haematologic disease (i.e., benign or malignant), we analyzed four patient groups (Figs. 4–7).

For details see legend of Fig. 2.

For details see legend of Fig. 2.

For details see legend of Fig. 2.

For details see legend of Fig. 2.

The prevalence of infertility was found to be highest in females with malignant diseases, at 65% (95% CI: 0.58–0.71) (Fig. 5). The prevalence of infertility in females with benign diseases was 61% (95% CI: 0.48–0.73) (Fig. 4). In males, the prevalence of infertility was lower and reached 41% in malignant diseases (95% CI: 0.32–0.51) (Fig. 7) and 31% (95% CI: 0.19–0.46) in benign diseases benign diseases (Fig. 6). Data heterogeneity was high in the female sex, as evidenced in malignant (I2 = 83%, p < 0.01) and benign (I2 = 65%, p < 0.01) cases. Also in males, data heterogeneity was high, both in malignant (I2 = 91%, p < 0.01) and benign (I2 = 74%, p < 0.01) cases.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to analyze the prevalence of gonadotoxicity after HSCT oncological treatment in patients with a history of both benign and malignant haematologic diseases to improve fertility counselling. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of joint prevalence of infertility after a multimodal set of oncological treatments.

Our review revealed the following important findings: First, the overall pooled prevalence of gonadal toxicity in the general population of cancer survivors who had previously undergone HSCT treatment was very high for women (64%; CI 95%: 58–70%) and moderately high for men (39%; CI 95%: 31–47%). Second, we observed a high prevalence of infertility in women both with malignant (65%; 95% CI: 0.58–0.71) and benign diseases (61%; 95% CI: 0.48–0.73).The prevalence of infertility in males with malignant diseases was 41% (95% CI: 0.32–0.51), while the corresponding prevalence in males with benign diseases was 31% (95% CI: 0.19–0.46).

In our review, we discovered six retrospective studies of good quality [31,32,33, 43,44,45]. Due to the predominantly mixed therapy study cohorts (i.e., various combinations/doses of chemotherapy and total body irradiation (TBI), aggregated outcomes, and mixed-age populations), it was not possible to perform subgroup analyses of the treatments that occurred in pre-and post-pubertal populations.

Gonadal failure is the most frequent endocrine complication of high-dose chemotherapy and radiotherapy after HSCT; recovery is a rare occurrence [31,32,33, 43,44,45,46]. The risk of hypogonadism increases with patient age at the time of HSCT in both sexes; the younger the age, the better the chance of gonadal recovery [26, 47]. Studies have associated gonadal failure with: older age (> 10 years) at the time of transplantation (in younger individuals there may be gonadal recovery), underlying malignant disease (AML/ALL/lymphomas), second remission of leukemia, cranial/pelvic/total body irradiation, alkylating agents, cisplatin, and nitrosoureas [48]. HSCT is a procedure that is commonly performed in children and young adults. Post-pubertal patients undergoing HSCT have been observed to exhibit higher rates of hypogonadism than their pre-pubertal counterparts. Furthermore, the risk is higher in girls than in boys and in those who receive allogeneic HSCT compared with autologous HSCT [48].

Our data suggest that HSCT is a significant risk factor for infertility in both pre- and post-pubertal females, as well as in males. Notably, women are more affected by infertility than men. In women, the prevalence of infertility remains unchanged regardless of whether the haematological disease is benign or malignant. Nevertheless, there is a slightly lower prevalence of infertility in men with benign haematological disorders than in those with malignant disorders. In the context of benign disease, it is crucial to consider the risk of infertility in both women and men undergoing HSCT in order to provide timely fertility preservation counselling.

Regarding female fertility, according to the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), premature menopause occurs in 8% of survivors and depends on age, ovarian irradiation dose, and cumulative dose of alkylating agents [49]. Alkylating agents impair follicular function, even in reduced-intensity regimens [26, 48,49,50,51,52,53]. We observed a significant association between BuCy and gonadal toxicity in our systematic review.In a study of adults, Güemes et al. found that women who developed primary hypogonadism were more likely to be treated with busulfan (Bu) for conditioning therapy prior to HSCT (40.6% vs 0%) [48]. Busulfan treatment is associated with higher rates of ovarian dysfunction [39, 48, 54]. A large study by Sanders et al. reported that only 1 in 73 women (1.3%) treated with busulfan/cyclophosphamide (Cy) recovered ovarian function. [55]. Furthermore, busulfan is known to be more gonadally toxic in women than in males [55]. More recently, Vatanen et al. evaluated a group of 92 surviving pubertal women confirming that preserved ovarian function is more frequent in patients conditioned with Cy alone compared to women primed with a regimen containing TBI (29%) or Bu-based (25%) [26]. The incidence of gonadal recovery was between 10% and 13.5% in female patients who received a conditioning regimen containing TBI [55]. Bresters et al. demonstrated that nearly half of girls who were pre- or post-pubertal at the time of HSCT required hormonal induction of puberty and described the association of busulfan with ovarian insufficiency in patients conditioned with chemotherapy alone [51]. In contrast, melphalan has been reported to have the potential to improve ovarian function [39]. Panasiuk et al. reported that girls treated with melphalan combined with fludarabine entered puberty spontaneously and required HRT to a lesser extent compared with girls receiving Bu/Cy [56]. Faraci et al. compared the effect of busulfan and treosulfan (Treo). For female patients, they observed that girls who received Treo during the prepubertal period more frequently reached puberty (menarche) compared to those treated with Bu. This suggests that Treo has a lower impact on pubertal development [25]. For reduced intensity conditioning (RIC), high rates of ovarian function preservation with melphalan-based reduced intensity conditioning have been reported [57]. However, this study neither measured Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), semen analyses, nor other parameters of fertility assessment, only follicle stimulation hormone (FSH) [57]. High-dose cyclophosphamide monotherapy is less gonadal toxic than BuCy, especially in young women [58].

Given the potential of RIC as a viable alternative for fertility preservation in HSCT, further studies and the possibility of establishing such a therapy should be considered 1.

Recovery from ovarian insufficiency has been previously described [51]. The prevalence of hypogonadism is higher in older adults [48], and the likelihood of recovery of gonadal function decreases by 20% with each additional year of age [59]. Some studies suggest that AMH may be a useful marker of ovarian follicular reserve in survivors of childhood cancer and/or HSCT [44, 60, 61]. However, although low AMH may be predictive of impending POI, pregnancies were reported to have occurred in women with low AMH values [62].

Regarding male fertility, Hypogonadism affects approximately 15% of young male cancer survivors aged 25–45 years [63]. However, the reported prevalence in studies of adults after allogeneic and autologous HCT varies widely, ranging from 6.9% to 84%. Key factors influencing prevalence include age at transplant, type of conditioning regimen, underlying diseases and previous treatments [64]. Leydig cells, which produce testosterone, are less sensitive to chemotherapy and radiation than the germinal epithelium, where sperm are produced. Recovery from hypogonadism is possible and can sometimes occur within the first year after transplantation [65,66,67,68,69,70]. However, before reaching a conclusion regarding a patient’s fertility status, it is essential to observe them for a longer period of time, potentially up to 9-10 years [71].

Although the gonadotoxicity of specific chemotherapies can be estimated using risk calculators (www.oncofertilityrisk.com), the assessment should be provided also for benign diseases requiring gonadotoxic treatment. As for the cyclophosphamide Equivalent Dose (CED) Calculator [72], it offers information about the risk of infertility but does not address the availability of multiple treatment options in the same way as other tools do.

There are some limitations to our study, although we strictly followed the recommendations to produce high quality evidence summaries: Firstly, most of the included studies were based on retrospective or registry data and lacked data on treatment protocols or dosimetry of chemotherapy combination and dosage, as well as combination with TBI as an important risk factor for long-term fertility outcomes. Secondly, the heterogeneity of the included studies, due to treatment variations and the diverse characteristics of the study populations, with wide age ranges, did not allow for further subgroup analyses depending on pubertal status, which is of great relevance for pre-treatment fertility protection measure counseling. Thirdly, the absence of data on the dosage of chemotherapy (in mg/m2 or CED) precluded the possibility of performing a sub-analysis of CED to assess the aggressiveness of the therapy. A standard conversion to m2 was not performed, in order to avoid bias in the results [72].

In conclusion, this first review and meta-analysis assessed the pooled prevalence of suspected infertility after HSCT in malignant and non-malignant haematologic disease. It provides clinically relevant information for fertility prognosis and patient counselling. Given the high prevalence of infertility and the associated risk of long-term complications, fertility preservation methods should be recommended prior to HSCT.

Responses