Fundamental questions in meiofauna research highlight how small but ubiquitous animals can improve our understanding of Nature

Results

Overview of the horizon scanning methods and main findings

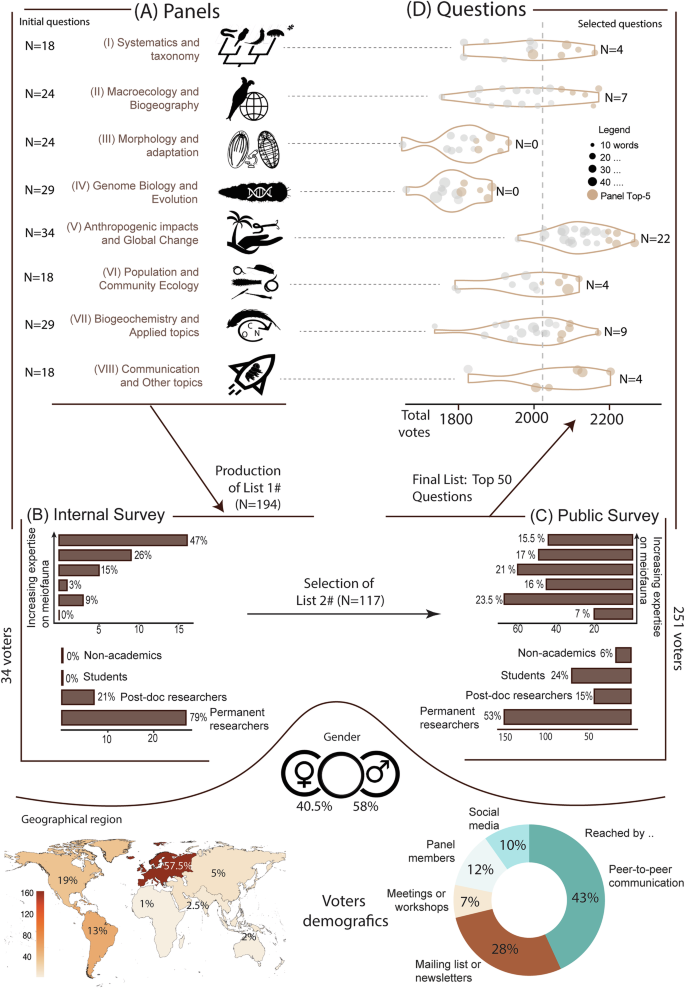

The two survey coordinators defined eight panels corresponding to areas within the published research in meiofauna (Table 1). After an internal poll, reducing the original 194 questions to a set of 117, our public online survey reached 251 voters using different platforms (Fig. 2), including researchers with and without a primary expertise in meiofauna. The highest ranked of the 117 selected questions for public voting scored 2257 points, whereas the lowest ranked scored 1640 points (Table 2). We summarised the voters’ geographical location, gender, age, level of meiofauna expertise, and career stage in Fig. 2. The scoring values in the responses were only marginally affected by the voters’ areas of expertise, gender, and age: these potential biases explained less than 11% of the total variance in the model explaining voters’ responses (Fig. 3; Supplementary Results). Thus, voters did not prioritise questions related to their own backgrounds. Additionally, question readability and word count did not significantly impact scores48,49 (Supplementary Results). Further information on the methods and caveats interpreting the results along with details on the survey scores and the anonymous voters’ metadata are included in the Supplementary Material50,51,52,53,54,55. Below, we summarise the results for each panel. We position the 5 highest-scoring questions per panel within future meiofaunal research in relation to the overall top-50 scoring questions.

A List of panels and number of questions (N) proposed by the panel members, after editing and removing duplicated questions. B The initial 194 non-redundant questions were reduced to 117 after voting by panel members and survey coordinators, and then (C) further to 50 after a public survey. D Results of the public survey by panel. Brown circles represent each panel’s 5 most-voted questions, size is proportional to the number of words. Numbers on the right show the number of the top-50 questions per panel (N). Lower panel shows the gender composition of respondents, geographical origin, and how they heard of our survey. Silhouettes drawn by Alejandro Martínez.

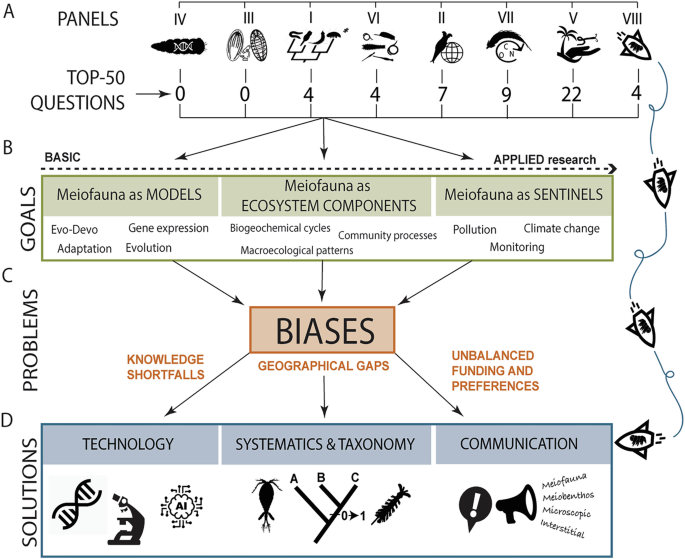

Panels are organized according to their focus, from basic to more applied research. A Applied questions received higher scores. B Questions have emphasised the role of meiofauna as eco-evolutionary models, their importance in ecosystem functioning and diversity across spatial scales, as well as their properties as sentinels for biomonitoring. C Knowledge shortfalls, gaps in geographic coverage, and the unbalanced preferences exhibited by researchers are major impediments affecting meiofauna research agenda. D Technological advancements, as well as improving and generalising taxonomic and communication skills as a research community will alleviate those issues. Attracting more students and researchers with diverse backgrounds will increase the utility of meiofauna to help us better understand Nature. Silhouettes drawn by Alejandro Martínez.

Panel I: Systematics and taxonomy

The “Linnaean shortfall”56 is particularly prominent in meiofauna research37, attributed to the time-consuming process of describing microscopic organisms6 and to the shortage of trained taxonomists compared to the vast undescribed meiofaunal diversity57. An accurate assessment of meiofaunal species diversity depends on the development of more efficient and reliable taxonomic procedures (Q#12). DNA metabarcoding is increasingly popular and promising for meiofauna biodiversity assessments58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66, though challenges remain. Firstly, diversity estimates depend on target genes and workflows tailored to low population density, small-sized animals, and uncertain genetic diversity67. Secondly, metabarcoding accuracy depends on well-curated reference databases to ensure the correct assignment of hypothetical species to DNA sequences. Thirdly, standardised pipelines are needed for comparability of the generated data68. Finally, most current methods produce short sequences, which, together with the high genetic diversity and high substitution rates across meiofaunal species, complicate species identification and the design of universal primers18,69,70,71.

Standardised taxonomic approaches57 and metabarcoding63 have boosted biodiversity estimates even in well-studied areas, highlighting the urge for community collaboration to map meiofauna species diversity at regional and global scales57,72,73,74 (Q#21). Comparative analyses across regions and habitats might reveal areas of endemism and biodiversity hotspots supporting the overall goal of identifying patterns of diversity across different taxa (Q#37). This is particularly relevant for testing the “Everything is Everywhere” hypothesis75, and the question on whether widely distributed species are robust biological entities or just an artefact of poor taxonomic resolution (Q#31). Several meiofaunal groups, like rotifers, nematodes, and tardigrades, have species with wide distribution ranges because their dormancy capabilities may enable long-distance passive dispersal76,77. However, most annelids, proseriates, rhabdocoels, and acoels lack such traits, so their reported cosmopolitan distributions depict a puzzling pattern referred to as the “meiofauna paradox”22,78. Recent morphological and molecular analyses have revealed that many supposed cosmopolitan species in poorly-dispersing meiofauna are actually species complexes with high molecular divergence and restricted geographical distribution ranges79,80,81, although some widespread species also remain82,83.

Understanding meiofauna biodiversity faces challenges with specimen preservation for reliable re-identification (Q#60). Advances in technology have outdated many old descriptions, and type material – if it exists – is often inaccessible for re-examination via modern methods. This problem prevails in “soft-bodied” meiofauna that requires live study of diagnostic characters84. A heated debate continues over the requirements of type material and the role of photomicrography-based taxonomy in “type-less species descriptions”85. Ideally, photomicrographs should be combined with a voucher suitable for DNA analyses, though thorough morphological documentation risks damaging or destroying the type to-be. Still, a damaged specimen can at least serve as voucher material in the form of a “DNA-type,” in agreement with the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature86,87.

Panel II. Macroecology and biogeography

Meiofauna, being widely distributed and ecologically diverse, serve as an effective model for exploring global biogeographical patterns and processes88. Meiofauna encompasses species from most animal phyla19, allowing researchers to examine the generality of global biodiversity trends beyond large organisms89,90. However, global meiofauna studies are limited by a lack of standardised sampling protocols, which hinders the collection of comparable data worldwide (Q#8). Long implemented for larger organisms, especially vertebrates, international protocols and data-sharing practices are still incipient in meiofauna research91,92, contributing to challenges in estimating their diversity at large scales.

Amongst the issues hindering robust estimations of meiofaunal taxonomic diversity (Q#13), the most pervasive factors include the prevalence of undescribed species, reliance on higher taxonomic levels, and biases towards regions such as Europe93. Many geographical areas remain unexplored for meiofauna, and even within well-investigated regions, species records are often concentrated near research facilities or specific habitats, distorting our understanding of species distribution and ecology94. While workshops around the world have facilitated some progress, they only cover limited areas within largely uncharted regions95.

Our understanding is even more restricted when it comes to functional and genetic patterns of diversity37, which is concerning since these aspects are crucial for inferring processes behind observed macroecological patterns57,67,94,96. Traits, phylogeny, and abiotic ranges might help to identify the factors determining species dispersal (Q#16), especially for morphologically similar populations that may differ in habitat requirements or fulfil various ecological roles97,98. Morphological traits57,77 or ecological preferences90,99 can facilitate long-distance dispersal through mechanisms such as rafting100, animal phoresy95,101, wind and rain-mediated transport102, or accidental transport via ship ballast water103. Understanding meiofaunal dispersal dynamics will clarify how ecological patterns are shaped by physical barriers and limitations – or advantages – related to their body size16.

Comparable datasets are also essential to explore large-scale drivers of meiofaunal biodiversity (Q#24, Q#38). However, existing datasets primarily rely on data mining from published studies, most of which are based on morphological identification90,104,105,106,107. Meiofaunal records are scarce in general open-source databases, such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), and often lack taxonomic validation or even an updated taxonomic backbone. Comprehensive databases do exist for certain groups (e.g., acoels108, platyhelminths109, tardigrades110,111, gastrotrichs112), geographical areas23,113,114,115,116,117,118 and habitats13,110. Unfortunately, global datasets have few available records for nematodes, copepods, and foraminifera, despite their abundance in sediments worldwide78. Future research efforts should prioritise interoperability by unifying database formats and terminology119, as well as integrating genetic120 and trait information121,122, to enhance big data-driven research.

Panel III. Morphology and adaptation

The advent of advanced microscopy and imaging technologies123, along with the challenges imposed by climate change and biodiversity loss emphasise the urgent need to understand morphology and adaptive mechanisms across animal groups124. Because the entire meiofaunal organism and its internal contents can be studied simultaneously with high-resolution microscopy, meiofauna are particularly well-suited models to spearhead morphological research. However, none of the panel’s proposed questions entered the top-50 priority list (Table 2). We attribute this to the voters’ preference for applied research and the specificity of the questions proposed by this panel, which may have addressed unfamiliar topics to broader audiences.

Three of the five highest-voted questions focused on convergent adaptation (Q#74, Q#84), and particularly, on the adaptive significance of small body size (Q#80). Small body size might be ancestral in some animal lineages39,41, while in others it likely evolved secondarily through miniaturisation processes125. Unfortunately, investigating adaptations over long phylogenetic timescales requires robust phylogenies, whereas currently available trees remain sensitive to the chosen phylogenetic reconstruction approach insofar as they rely on limited data for most meiofaunal lineages.

Research on adaptations over shorter evolutionary timescales relies on comparing the variability of traits and genetic variation across populations exposed to different ecological conditions124 (Q#92). This variability emphasises the importance of understanding gene expression plasticity in acclimation versus genetic differentiation when assessing phenotypic traits suited for changing environments126. Studies on meiofauna in this context remain rare compared to those on large-bodied animals127, despite recent collaborations among phylogeneticists, morphologists, and systematists having improved the integration of morphological and genomic data59,128,129,130.

The adaptive role of behaviour in meiofauna also remains unclear78 (Q#90). Understanding behaviour is not trivial because spatial patterns observed in meiofauna may result from the collective behaviour within populations responding to stimuli131,132. Pioneering studies on the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans Maupas, 1900133,134 pose the question of how behavioural responses across different meiofaunal groups may explain the relationship between the patchy distribution patterns exhibited by meiofauna and resource availability, as well as environmental variations at small spatial scales. However, behavioural studies are challenging, not only because of meiofauna’s small size, but also due to the difficulties in culturing most meiofaunal organisms135. Recent advancements in novel imaging techniques incorporating fluorescent nano-sensors, 3D bioprinting, microfluidic chambers, and geometric morphometrics offer potential for in situ observations of behaviours concerning environmental parameters at the relevant microscale136,137.

Panel IV. Genome biology and evolution

Genomic tools have advanced our knowledge of the evolutionary history of many animal lineages138,139, linking genotype to phenotype140,141, and aiding conservation efforts142. While the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans remains one of the quintessential biological model organisms, the lack of genomic data for most meiofaunal species hinders the integration of their evolution and ecology—a practice that has become commonplace in studies of larger organisms143.

Small body size presents technical challenges to acquiring genomic data for meiofauna but advances in complementary DNA (cDNA) library synthesis and amplification now enable high-quality transcriptome collection from meiofaunal animals with relative ease128,130. Whole-genome sequencing remains difficult; however, new kits can produce long-read sequencing libraries from minimal DNA concentrations, yielding high-quality genomes from (relatively) small animals such as mosquitos144 and springtails145. Emerging techniques such as multiple-displacement amplification146 and long-range PCR147 may facilitate high-quality genome assemblies from individual meiofaunal specimens or even their diapause eggs148. As these techniques become widely adopted, meiofauna will provide rich opportunities for comparative and population genomic studies. The low ranking of genomic questions in current research reflects the field’s status quo, which is poised for significant advancements not only from specific research groups but also due to the interests of several international initiatives, such as the Darwin Tree of Life149,150, European Reference Genome Atlas, and Earth BioGenome151 projects, which include meiofauna to increase high-quality genomic data across the Tree of Life.

Genomic tools applied to meiofauna have primarily been used to resolve their phylogenetic placement. Many microscopic animals occupy deep branches near the root of Bilateria, Spiralia, and Ecdysozoa and, therefore, are crucial in understanding character evolution across Metazoa152. This task is complicated by the rapid molecular evolution and long branches exhibited by some lineages, leading to artefactual groupings due to highly divergent sequences (Q#101)40,153,154,155,156. It remains unclear whether rapid genome evolution and other genomic traits observed in meiofauna can be attributed to intrinsic features such as small body size, short generation times, potentially large effective population sizes157 (Q#82) or whether these traits exhibit any geographical patterns, such as latitudinal gradients158 (Q#99).

Genomic tools are essential to understanding the adaptation of meiofauna to biotic and abiotic factors129,159, determining the tempo of morphological evolutionary change, and exploring cryptic species complexes (Q#88)87,160,161,162. As with cryptic species delimitation, population genomics enables insights into gene flow and reproductive isolation, providing powerful tests for evolutionary hypotheses (Q#85). By combining genomic inferences about gene flow and genetic differentiation163,164 with experimental measures of reproductive isolation165,166, meiofauna will provide complementary test cases to assess the generality of evolutionary hypotheses beyond large-bodied organisms. We anticipate that applying methods such as landscape genomics, which studies adaptation, connectivity, and speciation by associating allele frequencies and environmental conditions167,168 and macrogenetics, which searches for common trends in intraspecific genetic variation across many species169, will help elucidate the evolutionary ecology of meiofauna.

Panel V. Anthropogenic impacts and global change

Amid a global climatic emergency170 and accelerating biodiversity crisis171, it is not surprising that questions addressing anthropogenic impacts and global change overwhelmingly lead the scores, with 22 questions in the top-50 and seven in the top-10 (Table 2).

Meiofaunal diversity, an established indicator of aquatic ecosystem health35,172,173, typically declines with disturbance, though exceptions exist174. Meiofaunal communities, with rapid generational turnover and numerous species even in small samples, show rapid, detectable shifts in structure even following very small environmental changes such as minor differences in average temperature175,176. This sensitivity reflects trade-offs between resilient and vulnerable species (e.g., disturbance cause declines in sensitive species, while tolerant species maintain or increase their abundance), making meiofauna a valuable tool for monitoring ecosystem health172,177. Studying how taxonomic and functional meiofaunal diversity is linked to ecosystem functioning is important to mechanistically understand its contribution to the resilience and sustainability of ecosystems35,173 (Q#1, Q#2). However, to what degree those biodiversity metrics respond to anthropogenic impacts, including global change174,178, remains debated167.

Meiofauna have strong potential as bioindicators of anthropogenic impacts179,180 (Q#3, Q#5). Meiofauna’s limited mobility likely expose organisms to ongoing anthropogenic impacts throughout their entire life cycle. Their small size facilitates large-scale sampling with appropriate techniques, and their high diversity makes shifts in taxonomic or functional composition readily detectable34 over relatively short time scales. However, the effectiveness of meiofaunal organisms as indicators of ecosystem quality and function remains uncertain, primarily due to insufficient information on how community composition correlates with other ecosystem metrics.

Resilience has become an important research focus in the context of global change (Q#6). Understanding how to promote the ability of communities and ecosystems to recover from disturbance—whether sudden “pulsed events” like storms or gradual “press events” such as pollutant accumulation in the environment—is essential. Given their rapid reproduction and growth, meiofauna are promising indicators of ecosystem resilience181. Furthermore, meiofauna pioneer successional processes in disturbed ecosystems, often in close interaction with microbes, facilitating ecosystem recovery before larger organisms arrive and establish themselves182,183.

Panel VI. Population and community ecology

The study of population and community ecology using meiofauna faces biological and technical challenges that connect to: small size, identification problems—particularly of fixed specimens184,185—, and dominance of few species in many communities12,14,186,187,188. Furthermore, the assemblage of meaningful data at such a small spatial scale is biased by our perception of the microscopic world. All in all, the study of meiofauna community ecology remains in its infancy and, consequently, only four rather general questions of this panel entered the top-50 list (Table 2).

Understanding how connectivity influences meiofaunal diversity is essential to predict dispersal effectiveness through ecological corridors and stepping stone habitats189 in a meta-population dynamics context186 (Q#20). The spatial and temporal connectivity among habitats informs effective conservation strategies, especially in partially isolated habitats9,190, which meiofauna might predominantly reach via migration from local refugia.

Integrating approaches from terrestrial ecology may increase our chances to develop unified conceptual ecological theories52. However, the applicability of such theories to meiofauna remains uncertain (Q#30), because establishing unified theories requires improved knowledge on how microscopic organisms experience the environment (Q#32). The higher relative water viscosity at microscopic scales crucially affects how meiofauna sense their environment compared to larger organisms. Meiofauna show complex responses to stimuli133,134, mainly using mechano- and chemo-receptors for orientation and food detection42. Volatile organic compounds can trigger attraction towards food patches191, and food quality and quantity might critically activate feeding behaviours192, overruling competition or predation risk193. Light might also be an important stimulus in illuminated habitats shown for free-living nematodes194. Finally, at their microscopic scale, shear-stress and changes in osmotic and hydrostatic pressure could also be sensed by meiofauna195.

As performed by some macroscopic animals196,197, meiofauna can manage their favourite food to enhance survival (Q#51). Bacterial-grazing nematodes promote microbial mobility, while their burrows, pellets, or mucus structures sustain the growth of microbial populations198. Laboratory experiments show that increasing abundance of nematode populations can promote bacterial activity199 and photosynthesis200,201. Kinorhynchs secrete mucus to grow and trap microorganisms202; gutless nematodes and annelids rely on symbiotic bacteria to survive in low-oxygen environments203,204,205. Although it remains to be quantified, the gardening behaviour of meiofauna may have significant implications for ecosystem processes such as denitrification in marine sediments and organic matter decomposition30,206.

Overall, community ecology questions revealed the need for understanding meiofaunal interactions and connections across multiple scales, emphasising feedback from individual functioning and interactions to ecosystem dynamics within a selective abiotic setting (Q#40)207,208,209,210,211,212. Simulations integrating niche and dispersion measures have demonstrated that trait-phylogeny-environment relationships, and frequency-dependent population growth explain community assembly in marine nematodes213, similar to patterns observed in plants214. Likewise, including species traits in community ecology offers a promising avenue for moving beyond the “Everything is everywhere” paradigm for microscopic animals96,215. Furthermore, determining the individual phenotypes, behaviours, and mechanisms for how meiofauna sense and react to the contemporary environment is essential to understand the functional diversity of meiofauna216.

Panel VII. Biogeochemistry and applied topics

Meiofauna probably shape ecosystems worldwide, although it is in soils and sediments where we know that meiofauna catalyse globally important processes through burrow construction, ingestion and egestion, and the flushing of overlying water for respiration and feeding28,31,217. Therefore, questions of this panel received high scores highlighting the need for further research in this relatively underexplored, yet relevant field28.

Meiofauna primarily influence oxygen, sulphur, carbon, and nutrient cycles through direct solute uptake and bioturbation218,219,220, stimulating nitrogen cycling microbes30, and interacting with cable bacteria in anoxic sulphide-rich coastal sediments221 (Q#9, Q#28). Most meiofauna require relatively high levels of oxygen and organic matter, which leads them to primarily inhabit and bioturbate the upper layers of soil and sediment32. The role of meiofauna from deeper sediment layers in ecosystem processes remains poorly understood. Respiration rates of meiofauna significantly decrease in response to decreasing ambient oxygen levels33,222. Muddy sediments dominate most of the seafloor and promote active meiofauna bioturbation that affects solute transport and microbial community structure30,33,206,221. Conversely, foraminifera promote sediment reworking in sandy environments common in intertidal and shelf areas16,17. However, the role of meiofauna in other ecosystems, such as the deep sea223 as well as their influence on the cycling of other macronutrients, such as phosphorus, remain poorly understood.

The direct contribution of meiofauna biomass to total sediment carbon stocks is small224 (Q#27). However, meiofauna activity significantly modifies carbon exchange at the sediment-water interface, potentially increasing bacterial carbon mineralisation by up to 50%206. Meiofauna contribute 3–33% of total oxygen uptake in coastal sediments33, influencing the carbon chemistry of overlying seawater and possibly altering carbon sequestration in sediments across large spatial scales, although their net effect remains unquantified225. Interestingly, meiofauna can mediate ecosystem processes in sediments with minimal or no macrofauna as observed in the deep sea226 and hypoxic Baltic Sea areas227.

Past research has revealed the significant yet largely unexpected role of meiofaunal-prokaryote interactions in benthic ecosystem processes, including organic matter remineralisation206 and organic pollutant degradation228,229 (Q#35). However, empirical data on the effect that meiofauna have on the fate and distribution of heavy metals is lacking (Q#39). Effects of meiofaunal activity on microplastics have also received little attention. Annelids230,231 and nematodes232,233,234 might accidentally ingest microplastics, but it remains unknown how meiofaunal bioturbation affects microplastic transport and fate in the sediment. Future experimental and modelling studies are necessary to understand how meiofauna-prokaryote interactions evolve under anthropogenic stress and their potential in biodegradation and water treatment technologies.

Panel VIII. Science communication and other topics

Despite being hardly visible to the naked eye, meiofauna stand out by the astonishing number of species and variety of forms (Fig. 1), even in places where more conspicuous life forms are scarce14,188,235. Indeed, meiofauna includes representatives from at least 23 out of 35 animal phyla. However, the total number of species remains uncertain, with estimates ranging from 10 to 107, the vast majority of which are yet to be described236. The high probability of describing new species may attract taxonomists to study meiofauna, and the description of unexpected life forms and morphologies could appeal to researchers focused on animal evolution237,238 (Q#4). Microscopic animals might also help us address broad eco-evolutionary questions, once data on their biology, distribution, and genetics are available (see discussion above). This diversity of topics offers training in complementary disciplines, fostering a new generation of meiobiologists.

Researchers interested in applied sciences may value meiofauna for their practical role in ecosystem conservation and management34,188,239,240,241 (Q#19). Certain microscopic species, particularly the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, have helped us understand human disease to eventually lead to cures or treatments47,242,243. Soil nematodes and other soil microscopic animals—more commonly referred to as mesofauna—are fundamentally important in agriculture244. Despite their importance, meiofauna are often underrepresented in discussions of practical applications.

Students are likely to engage in meiofauna studies if first introduced to the topic during their early academic programmes (Q#44). Although not many university courses focus on meiofauna, several summer schools and extracurricular courses have made them a central element72,74,245. Those courses often include workshops led by renowned researchers, who teach but also collect and describe the local biodiversity246,247,248. This approach brings knowledge and resources to areas where biodiversity research is limited, often leading to joint publications72,74.

Early career researchers interested in biodiversity can contribute to building baseline datasets and catalogues of aquatic life, including meiofauna113,114,118. New technologies, such as DNA-based taxonomy71,249, rapid DNA fingerprinting techniques29,250, and automated high-resolution imaging combined with machine learning could alleviate taxonomic impediments, ultimately enabling reliable assessments of meiofauna diversity (Q#22).

Meiofauna can be used to enhance awareness of Earth’s ecosystems and the biodiversity crisis, through interactive talks, hands-on activities, and scientific workshops (Q#57)251. Meiofauna diversity has been highlighted in accessible books and fairy tales for children252,253. National Parks and UNESCO Geoparks can support dissemination efforts by integrating research with outreach initiatives73,254,255. Remarkably, some microscopic animals have gained popularity in internet culture through memes and videos: tardigrades are famous for their toughness46, bdelloid rotifers for the lack of males256, and mud dragons (kinorhynchs) or penis worms (priapulids) for their evocative morphologies257. Creative naming of new species after unique morphological features or famous artists might also bring them into the spotlight258,259,260.

Discussion and future directions: the next generation of meiofauna research

Are we exploiting the full potential that meiofauna offer as a model to address questions of broad scientific and societal importance?

The answer is no, or at least not yet. There are a number of key challenges and biases that adversely affect our current knowledge of meiofauna (Table 3). Nevertheless, integrative approaches and technological developments have been creating opportunities to use these fascinating organisms to address broad and important questions28 (Fig. 3). Meiofauna have been used as models to understand fundamental adaptive processes, they have contributed to unravelling the animal Tree of Life39, they are predicted to contain a treasure trove for future genomic studies125, they play key roles in ecosystem functioning and integrity30,31, and they have been used as models to understand human diseases47. Meiofauna also represent a valuable biomonitoring tool for freshwater and marine environments alike, even where larger-sized fauna have become depleted or absent34,35,261. This very broad spectrum of topics is just the tip of the iceberg, with new ideas and research avenues continuing to emerge as technological developments and accumulation of information shed light on the fascinating life of the microscopic, ubiquitous animals around us.

What are the critical research priorities?

Our research agenda should balance the investigation of general questions—sparking the interest of a broad audience—and address specialised research topics focusing on theoretical aspects concerning meiofauna (Fig. 3). The latter aspects, which often involve generating primary data on distribution, taxonomy, traits, and DNA sequences, are not only critical to address some of the knowledge shortfalls that pervasively affect the development of the field59, but are also foundational for supporting applied science.

The results of our survey, largely favouring questions with a more applied scope, contrast with the diverse research topics initially proposed by our panels and traditionally tackled by meiofauna researchers. Survey responses were not influenced by the background of the voters (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Methods), nor by the linguistic features of the questions (readability, length, use of jargon and acronyms). Whether survey responses were influenced by other factors not controlled for in our analysis, such as the current funding landscape or the growing eco-anxiety, rests in the mind of each voter. Regardless, survey results should not be accepted uncritically as a roadmap guiding research priorities; rather, they should be viewed as a diagnosis of how broad international audiences perceive the importance of the different topics addressed traditionally in meiofauna research.

Which biases currently affect meiofauna research and how can we overcome them to move forward with the research agenda?

Geographical and taxonomic biases, as well as biases inherent to the small size of meiofauna, have affected meiofauna research37. Therefore, it is unsurprising that they were the focus of many top priority questions of each panel (Fig. 3).

Technological innovation might alleviate some of those biases. New imaging and microscopy technologies, for example, have provided unprecedented insights into meiofauna. Artificial intelligence and molecular methods might soon expedite sample processing and analyses. Implementing these methods, though, requires urgent training of taxonomists to create essential reference databases of images and DNA, as well as optimising sequencing technologies for small meiofaunal organisms. Whilst reduced genome representation methods and transcriptomics can offer interim solutions262,263, the full potential lies in generating complete reference genomes. To achieve this, greater collaborative and development efforts are essential.

Geographical gaps will only be overcome through the establishment of international collaborations264. The International Association of Meiobenthologists plays an important role, including periodically organised conferences and thematic sessions at international meetings. Summer schools and regional workshops have proven useful as well, especially in engaging local students and researchers from areas with limited resources available to study meiofauna. Improving communication skills is crucial in reaching diverse audiences and making the research community even more international and diverse.

In conclusion, meiofauna have many desirable properties to address a broad range of research questions, but those advantages are often overrun by a range of shortfalls and impediments. It is our task as a research community to turn these impediments into exciting opportunities, which potentially get both researchers and the broader public intrigued by those small critters that constantly lurk unseen around us.

Material and Methods

To identify fundamental questions addressable using meiofauna52, we applied a horizon scanning methodology, proven effective in similar studies54,55. Two survey coordinators defined eight panels, each with a panel coordinator (Table 1) to form an international expert panel tasked with drafting initial questions. Each panel included two renowned meiofauna experts, an early-career researcher, and an external expert with relevant expertise on the topic of the panel outside meiofauna.

Panels assembled an initial list of 253 questions, which was first reduced to 194 questions after removing duplicates and improving readability (see Supplementary Methods)50,51,265. Then, 32 panel members and 2 survey coordinators (total 34 voters) scored questions in List #1 from 1 to 10. The scores ranged from 266 (top-voted question) to 120 (least-voted question). Based on a bimodal distribution of scores, the best 117 questions scoring above 205 were included in List #2.

List #2 underwent public voting via an online survey, targeting a broad audience, including meiofauna specialists, non-specialists, students, and stakeholders. The survey was promoted through direct emails, social media (Facebook, Twitter, ResearchGate), workshops, meetings, newsletters (e.g., International, Brazilian and Japanese Association of Meiobenthologist), and mailing lists (e.g., rotifer-family@listserv, Annelida, International Society for Subterranean Biology, Italian Ecological Society, Ecological Society of India). Panel members also shared it with students in their courses.

Caveats of horizon scanning surveys and our countermeasures in the statistical methods are discussed in the Supplementary Material.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses