Stress-induced GHS-R1a expression in medial prefrontal cortical neurons promotes vulnerability to anxiety in mice

Introduction

Experiencing occasional anxiety is a normal part of life; however, people with anxiety disorders frequently have intense, excessive and persistent worry and fear that interfere with daily activities. The neural substrates of anxiety and related disorders are not fully understood. Stressful life experiences such as traumatic events appear to trigger anxiety disorders in individuals who are already prone to anxiety1. Laboratory studies have also shown that repeated stress exposure, such as chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) and chronic social defeat stress (CSDS), triggers anxiety-related behavior in rodents2,3,4,5,6.

GHS-R1a is the only known functional receptor for ghrelin, a peripheral hormone that controls hunger and energy balance and may play a key role in stress-induced homeostatic processes7. GHS-R1a is distributed in the brain and is enriched in key nodes of neural circuits related to emotion, cognition and reward, such as the hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and hypothalamus8. Circulating acyl-ghrelin (the active form) is elevated not only in mice exposed to CSDS or CUMS9,10 and rats exposed to chronic restraint stress6, but also in vulnerable adolescents exposed to chronic severe stressors7. Therefore, studies have suggested that ghrelin is not only a “hunger” hormone but also a persistent biomarker for stress6,8,9,10,11. However, how ghrelin/GHS-R1a signaling participates in the development of stress-induced anxiety or depression is unclear. For instance, previous studies have reported that GHS-R1a knockout does not affect anxiety-like behavior12, while other studies have shown that it enhances depression-like behavior in non-stressed mice through suppression of neurogenesis and spine density in the hippocampus13. In contrast, our previous study showed that GHS-R1a deficiency alleviated CSDS-induced anxiety- and depression-related behaviors in mice14. The reason for these conflicting findings remains unclear, and it is necessary to reveal the mechanisms mediating the effect of ghrelin and GHS-R1a on mood regulation.

The mPFC mainly consists of the prelimbic (PrL) and infralimbic regions (IL), which are known to be involved in regulation of anxiety, fear, reward, and social behavior with distinct mechanisms15,16,17,18. Previous studies have shown that optogenetic activation of glutamatergic neurons in PrL exerts anxiolytic effects in mice19. However, the IL-LS (lateral septum) projection promotes anxiety-related behavior and fear-related freezing, the IL-CeA (central amygdala) projection has anxiolytic and fear-releasing effects17. Functional disruption of glutamatergic neurons in the mPFC has been observed in individuals with stress-related neuropsychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety and depression, in both humans and rodents20,21,22. For instance, studies have confirmed that stress exposure triggers atrophy and loss of layer 5 pyramidal neurons in the mPFC23. Dysregulation of serotonin and receptors 5-HT1A/5-HT2A signaling promotes E/I imbalance in mPFC pyramidal neurons, and contributes to early adversity in individuals with stress-induced psychiatric disorders24.

Moderate GHS-R1a expression in the PrL has been identified using GHSR-eGFP mouse25. The fact that administration of GHS-R1a antagonist JMV2959 alters neuronal responses to ghrelin in the mPFC26, further suggesting that the mPFC may be an important region mediating the biological functions of ghrelin and GHS-R1a, including anxiety regulation. αCaMKII is the most abundant protein in excitatory synapses within the CNS. It detects subtle variations in intracellular calcium concentration and plays a crucial role in regulating receptor trafficking, excitatory neurotransmission, synaptic plasticity, and neuronal signaling27,28. aCaMKII+ neurons constitute a significant population of excitatory neurons in the mPFC and hippocampus29. In previous studies, we have reported GHS-R1a expression in hippocampal αCaMKII+ neurons and its importance in memory regulation30,31. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that ghrelin/GHS-R1a signaling in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons may regulate stress response and anxiety-related behaviors.

In this study, we observed a delayed increase in GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons, coinciding with the development of RRS-induced enhancement of anxiety-related behavior. We combined chemogenetic techniques, fiber photometry, electrophysiological recordings, and behavioral assays to elucidate how GHS-R1a in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons regulates anxiety-related behavior. Our findings revealed that GHS-R1a is an important molecular switch that promotes anxiety-related behavior by shaping the synaptic activity of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons, providing new insights for the treatment of stress-induced anxiety disorders.

Results

RRS exposure enhances anxiety-like behavior and alters the activity of mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons

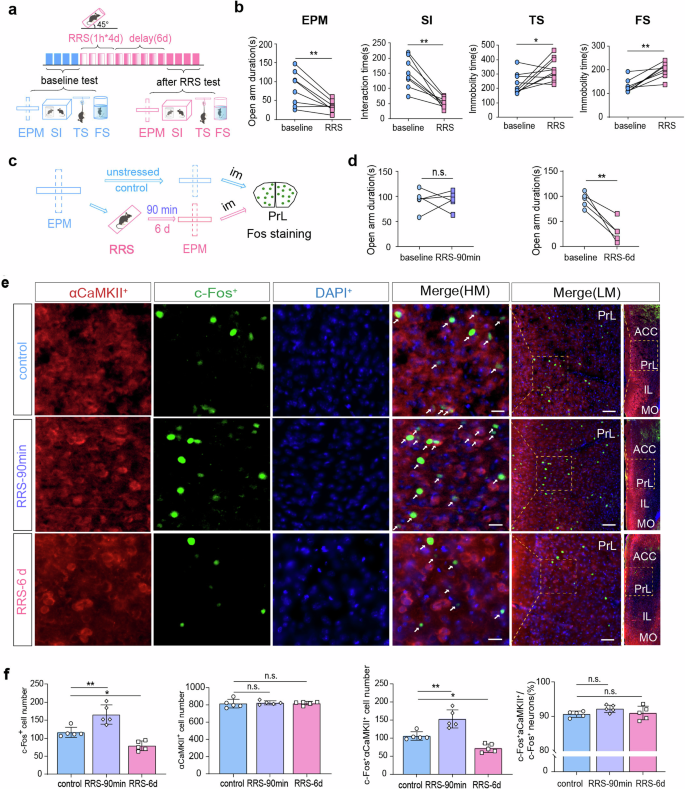

First, we confirmed that mice exposed to RRS (1 h/d for 4 d) exhibited enhanced anxiety-related behavior, as indicated by reduced open-arm exploration time in the EPM test, reduced sociability in the SI test, and increased immobility time in the TS and FS tests 6 d following stress exposure (Fig. 1a, b; paired t-test, baseline vs. RRS, EPM: t = 3.84, **P < 0.01; SI: t = 4.18, **P < 0.01; TS, t = 2.81, *P < 0.05; FS: t = 4.99, **P < 0.01). Dramatic RRS-induced behavioral changes were observed 6 d compared to 90 min after stress exposure (Fig. 1c, d; paired t-test, baseline vs. RRS-6 d, t = 5.39, **P < 0.01; baseline vs. RRS-90 min, t = 0.06, P > 0.05), indicating a time delay between stress exposure and the development of anxiety-related phenotypes.

a A flow chart of behavioral experiments design. This figure was created using BioRender (https://www.biorender.com/). b Behavioral testes carried out under baseline conditions and at 6 d after RRS exposure (1 h/d for 4 d). Paired t-test, n = 8 mice. c A flow chart of c-Fos immunostaining experiments. Im, Immediately. This figure was created using BioRender(https://www.biorender.com/). d EPM tests conduct before (baseline), at 90 min or 6 d after RRS exposure. Paired t-test, n = 5 mice per group. e Representative images showing co-expression of c-Fos and αCaMKII in PrL neurons. Scale bar, 20 μm for HM images (high magnification) and 100 μm for LM images (low magnification). White arrows indicate double-labeled neurons. f Cell quantification in the PrL. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 5 mice per group. All bar graphs represent mean ± SEM.

We verified the abundant expression of Camk2a and the sparse expression of Gad in mPFC neurons using FISH (Supplementary Fig. 1). These findings confirm that αCaMKII+ excitatory neurons represent the predominant neuronal population in the mPFC. We also quantified c-Fos expression in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons, including both PrL (Fig. 1c–f) and IL (Supplementary Fig. 2) regions, at 90 min and 6 d following RRS exposure, respectively. Although stressed mice did not exhibit decreasing open-arms exploration time at 90 min after RRS (Fig. 1d), immunostaining analyses immediately after the EPM test disclosed a significant increase in c-Fos expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons (Fig. 1e, f; One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, c-Fos+ cells: F(2,12) = 25.76, P < 0.0001, control vs. RRS-90 min, **P < 0.01; c-Fos+αCaMKII+ cells: F(2,12) = 27.43, P < 0.0001, control vs. RRS-90 min, **P < 0.01; αCaMKII+ cells: F(2,12) = 0.12, P > 0.05). In contrast, stressed mice showed enhanced anxiety-related behavior at 6 d after RRS (Fig. 1d), while their c-Fos expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons was reduced (Fig. 1e, f; One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, c-Fos+ cells: control vs. RRS-6 d, *P < 0.05; c-Fos+αCaMKII+ cells: control vs. RRS-6 d, *P < 0.05). Over 90% of c-Fos+ neurons in the PrL region were found to co-express αCaMKII across all three groups of mice (Fig. 1f; One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, c-Fos+αCaMKII+/c-Fos+ cells: F(2, 12) = 1.89, P > 0.05). These findings suggested that the activity of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons might be negatively associated with anxiety-related behavior in mice. Different from PrLαCaMKII+ neurons, ILαCaMKII+ neurons demonstrated persistent increase in c-Fos expression at both 90 min and 6 d after RRS exposure (Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting that ILαCaMKII+ neurons may play a distinct role in regulating anxiety-related behavior compared to PrLαCaMKII+ neurons.

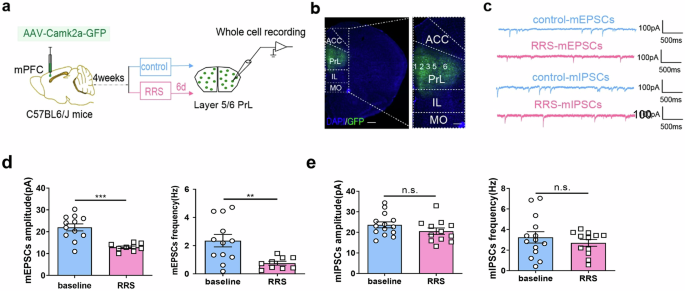

Previous studies reported that CSDS exposure reduced the frequency of mEPSCs in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons32. Consistently, our whole-cell patch clamp recordings revealed that both the amplitude and the frequency of mEPSCs in layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons were lower at 6 d after RRS exposure than under control, non-stressed conditions (Fig. 2a–d; Unpaired t-test, control vs. RRS, mEPSCs amplitude: t = 4.73, ***P < 0.001; mEPSCs frequency: t = 3.02, **P < 0.01). In contrast, RRS exposure did not affect either the frequency or the amplitude of mIPSCs in layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons (Fig. 2c, e; Unpaired t-test, control vs. RRS, mIPSCs amplitude: t = 1.44, P > 0.05; mIPSCs frequency: t = 0.80, P > 0.05). Since reduced c-Fos expression and suppressed excitatory synaptic drive of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons coincides with increased anxiety-like behavior in mice at 6 d after RRS, we presume that PrLαCaMKII+ neurons may respond to stressor and activate adaptively to protect mice against the development of stress-induced anxiety.

a Experimental design for whole-cell patch clamp recordings in acute mPFC slices. This figure was created using BioRender(https://www.biorender.com/). b Representative image illustrating viral infection in the PrL. GFP (green), DAPI (blue). Scale bar, left: 500 μm; right: 200μm. c Representative mEPSCs and mIPSCs traces recorded in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons under control, non-stressed conditions and at 6 d after RRS exposure. d mEPSCs comparison. e mIPSCs comparison. d, e Unpaired t-test, n = 4–5 mice per group (2–3 slices each mouse). All bar graphs represent mean ± SEM.

PrLαCaMKII+ neurons undergo activity changes during EPM exploration

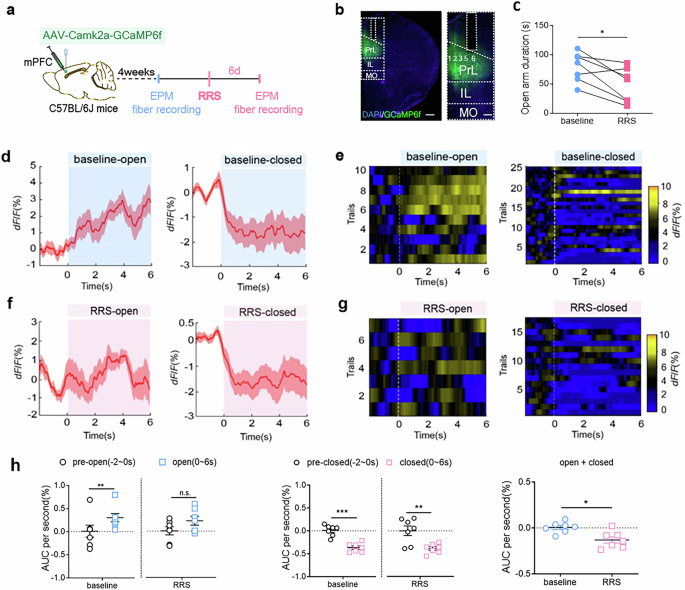

We used in vivo fiber photometry to investigate the dynamic activity of layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons during mice explored the EPM, a well-accepted paradigm for evaluating anxiety-like behavior33. The Ca2+ signal, an indicator of neuronal activity, were measured first under baseline, non-stressed conditions (before RRS exposure) and then at 6 d after RRS (1 h/d for 4 d) in the same group of mice (Fig. 3a–c and Supplementary Fig. 3). The Ca2+ activities of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons increased when mice entered the open arms of the EPM at baseline state, but not after RRS exposure (Fig. 3d–h; paired t-test, pre-open vs. open, baseline: t = 3.771, **P < 0.01; RRS: t = 1.588, P > 0.05). In contrast, the Ca2+ activities decreased when mice entered the closed arms of the EPM, both at baseline states and after RRS exposure (Fig. 3d–h; paired t-test, pre-closed vs. closed, baseline: t = 6.176, ***P < 0.001; RRS: t = 4.070, **P < 0.01). Overall, PrLαCaMKII+ neurons displayed reduced Ca2+ activities 6 d post-RRS exposure compared to the baseline state during both open- and closed-arms exploration in the EPM (Fig. 3h right; paired t-test, baseline vs. RRS, t = 2.72, *P < 0.05).

a A flow chart of experimental design. This figure was created using BioRender(https://www.biorender.com/). b Virus-mediated GCaMP6f expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons and fiber implantation in the PrL. Scale bar, left: 500 μm; right: 200 μm. c Open-arm duration in the EPM test. Paired t-test, n = 7 mice. d, f Representative in vivo calcium activity traces of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons during open (left)- and closed (right)-arms exploration in the EPM test. Baseline conditions (d), 6 d after RRS exposure (f). e, g Representative in vivo calcium fluorescence heat maps. Baseline conditions (e), 6 d after RRS exposure (g). h Calcium signals comparison at baseline state and after RRS exposure. Left, comparing AUC per second between pre-entry (−2 to 0 s) and entry (0–6 s) of open arms. middle, comparing AUC per second between pre-entry (−2 to 0 s) and entry (0–6 s) of closes arms. right, comparing AUC per second between baseline and post-RRS during open- and closed-arms exploration. Unpaired t-test, n = 7 mice. All bar graphs represent mean ± SEM.

Activating PrLαCaMKII+ neurons reduces anxiety-like behavior

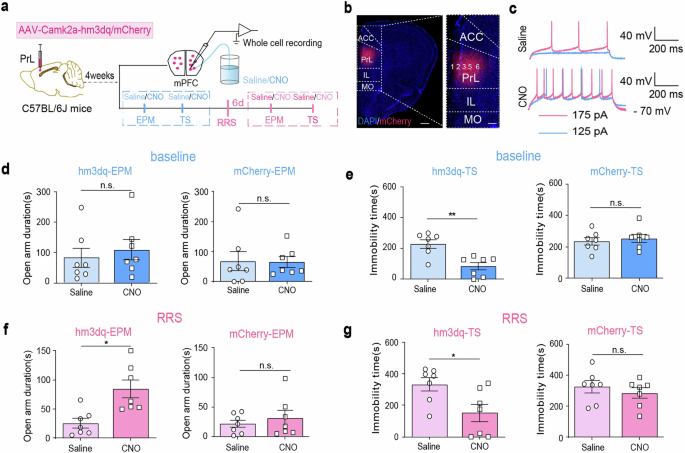

Next, we explored whether chemogenetically activating PrLαCaMKII+ neurons could reduce anxiety-like behavior. AAV-Camk2a-hm3dq-mCherry or control AAV-Camk2a-mCherry virus was delivered into the PrL region of C57BL/6 J mice 4 weeks before behavioral tests or electrophysiological recordings (Fig. 4a, b). CNO-mediated firing increase in layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons was confirmed via ex vivo whole-cell current-clamp recordings (Fig. 4c). The EPM and TS tests were performed first under baseline (unstressed) conditions and then at 6 d after RRS exposure. CNO administration did not alter the open-arm exploration time of hm3dq-expressing mice in the EPM test under baseline conditions (Fig. 4d left; paired t-test, t = 0.50, P > 0.05); however, it did reduce their immobility time in the TS test (Fig. 4e left; paired t-test, t = 4.19, **P < 0.01). Strikingly, activating PrLαCaMKII+ neurons via CNO administration increased the amount of time stressed mice spent in the open arms during the EPM test (Fig. 4f left; paired t-test, t = 3.41, *P < 0.05) and reduced the immobility time of those mice during the TS test (Fig. 4g left; paired t-test, t = 3.02, *P < 0.05). As expected, CNO administration had no effect on control mCherry-expressing mice, either under baseline conditions (Fig. 4d, e right; paired t-test, EPM: t = 0.20, P > 0.05; TS: t = 1.12, P > 0.05) or after RRS exposure (Fig. 4f, g right; paired t-test, EPM: t = 0.90, P > 0.05; TS: t = 1.74, P > 0.05). Thus, we confirmed that selective activation of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons attenuated anxiety-related behavior.

a The experimental design. This figure was created using BioRender (https://www.biorender.com/). b Representative images illustrating viral infection in the PrL. DAPI (blue), mCherry (red). Scale bar, left: 500 μm, right: 200 μm. c Representative whole-cell current clamp recordings in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons with bath application of saline or 3 µg/ml CNO. d, e, The effect of chemogenetic activation of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons on anxiety-related behaviors under baseline conditions. EPM tests (d), TS tests (e), paired t-test, n = 7 mice. f, g The effect of chemogenetic activation of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons on anxiety-related behaviors 6 d post-RRS. EPM tests (f), TS tests (g), paired t-test, n = 7 mice. All bar graphs represent mean ± SEM.

RRS induces delayed upregulation of GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons

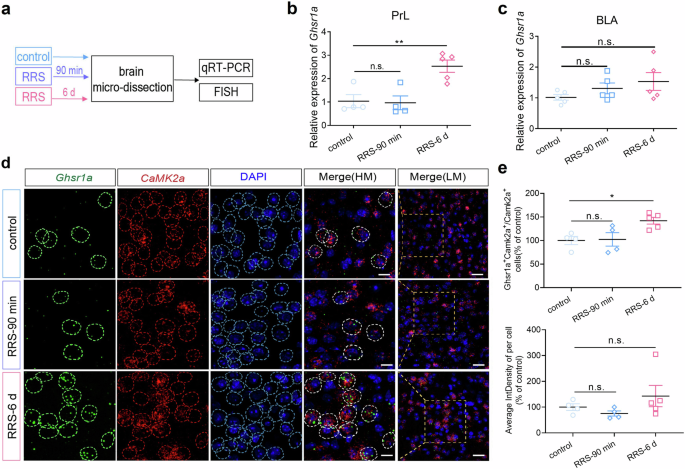

Both mice and adolescent individuals who are exposed to chronic stress exhibit a prolonged increase in circulating ghrelin4,7. We investigated RRS-induced changes in central GHS-R1a expression (Fig. 5a). Our RT–qPCR assays indicated that GHS-R1a transcript levels in the PrL were significantly increased at 6 d but not 90 min after RRS insult (Fig. 5b; One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, F(2,10) = 10.81, P < 0.01, control vs. RRS-90 min, P > 0.05; control vs. RRS-6 d, **P < 0.01). In contrast, RRS exposure did not significantly affect GHS-R1a expression in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) at either 6 d or 90 min after RRS exposure (Fig. 5c; One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, F(2,12) = 1.64, P > 0.05). We confirmed increased GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons at 6 d, not 90 min, after RRS exposure by FISH (Fig. 5d, e). The percentage of Ghsr1a+Camk2a+ neurons in PrL αCaMKII+ neurons increased at 6 d, not 90 min, after RRS exposure (Fig. 5e, One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, F(2, 10) = 5.88, P < 0.05, control vs. RRS-90 min, P > 0.05; control vs. RRS-6 d, *P < 0.05). The average fluorescence intensity density of Ghsr1a in individual Ghsr1a+Camk2a+ neurons also trended to increase at 6 d after RRS (Fig. 5e, One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, F(2, 10) = 1.42, P > 0.05). Taken together, our findings indicate that RRS exposure induces a delayed increase in GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons, which coincides with the development of RRS-induced enhancement of anxiety-related behavior.

a The experimental design. b RT-qPCR assays of Ghsr1a expression in the PrL. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 4–5 mice per group. c RT-qPCR assays of Ghsr1a expression in the BLA. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 5 mice per group. d Representative FISH images showing Ghsr1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons. Scale bar, 10 μm in HM (high magnification), 20 μm in LM (low magnification). e Cell number and Ghsr1a expression quantification in FISH studies. Upper, Percentage of Ghsr1a+Camk2a+ neurons in total PrLCamk2a+ neurons. Lower, The average fluorescence intensity density (IntDensity) of Ghsr1a in indivadual Ghsr1a+Camk2a+ PrL neurons. Data were normalized by control group before comparison. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 4–5 mice per group (4–5 brain sections each mouse). All bar graphs represent mean ± SEM.

Reducing endogenous GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons alleviates anxiety-like behavior

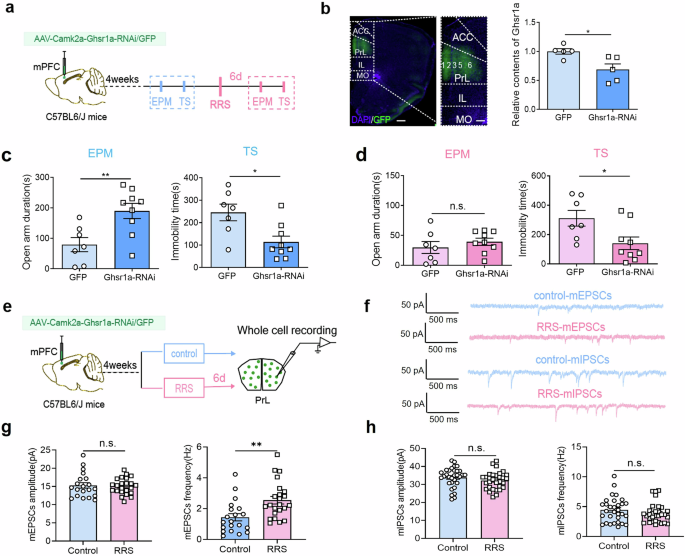

We first assessed the anxiety-like behavior both under baseline conditions and at 6 d after RRS exposure in GHS-R1a global knockout mice (GHS-R1a KO) (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c). There were no behavioral differences between WT and GHS-R1a KO mice under baseline unstressed conditions (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Noticeably, GHS-R1a KO mice exhibited similar open-arm exploration time in the EPM test and similar social interaction times in the SI test at 6 d following RRS exposure as under baseline conditions (Supplementary Fig. 4c; paired t-test, control vs. RRS, EPM: t = 2.122, P > 0.05; SI: t = 1.244, P > 0.05), suggesting an anxiolytic effect of GHS-R1a deficiency. In addition, Layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons in GHS-R1a KO mice exhibited increased mEPSCs frequency and decreased mIPSCs amplitude 6 d post-RRS exposure compared to baseline controls (Supplementary Fig. 4d–f; unpaired t-test, control vs. RRS, mEPSCs amplitude: t = 0.04, P > 0.05; mEPSCs frequency: t = 4.85, ***P < 0.001; mIPSCs amplitude: t = 2.33, *P < 0.05; mIPSCs frequency: t = 0.28, P > 0.05). The increased excitatory synaptic transmission and decreased inhibitory synaptic transmission observed in Layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons of GHS-R1a KO mice may contribute to reduce vulnerability to stress-induced anxiety. To further investigate whether selectively disrupting endogenous GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons reduces anxiety-like behavior, we delivered AAVs expressing Camk2a-driven Ghsr1a-specific shRNA or scramble shRNA to PrL region in C57BL6/J mice (Fig. 6a, b). RT-qPCR assays confirmed the reduction of endogenous Ghsr1a expression in the PrL region (Fig. 6bright; unpaired t-test, control vs. Ghsr1a-RNAi, t = 2.907, *P < 0.05). Behavioral analyses showed that RNA interference in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons significantly increased the open-arm exploration time in EPM test and decreased the immobility time in TS test under baseline conditions (Fig. 6c; unpaired t-test, control vs. Ghsr1a-RNAi, EPM: t = 3.03, **P < 0.01; TS: t = 2.84, *P < 0.05). Moreover, it reduced the immobility time in stressed mice (Fig. 6d; unpaired t-test, control vs. Ghsr1a-RNAi, TS: t = 2.521, *P < 0.05). Therefore, we conclude that disrupting endogenous GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons is anxiolytic.

a Behavioral experiment design. AAV virus expressing Ghsr1a-specific shRNA or scramble shRNA was delivered to PrL of C57BL6/J mice. This figure was created using BioRender(https://www.biorender.com/). b Representative images and RT-qPCR assays of Ghsr1a expression in the PrL. Left, Sample illustration of viral infection in the PrL. GFP (green), DAPI (blue). Scale bar, left: 500 μm, right: 200 μm. Right, RT-qPCR assays of Ghsr1a expression in the PrL region. Unpaired t-test, n = 5 mice per group. c, d The effect of reducing Ghsr1a expression in the PrLαCaMKII+ neurons by RNA interference on anxiety-related behavior. EPM and TS tests under baseline conditions (c), EPM and TS tests at 6 d after RRS exposure (d), unpaired t-test, n = 7–9 mice per group. e Electrophysiological experiment design. This figure was created using BioRender(https://www.biorender.com/). f Representative mEPSCs and mIPSCs traces recorded in virus-infected PrLαCaMKII+ neurons in control, unstressed mice and stressed mice at 6 d post-RRS exposure. g mEPSCs comparison. Unpaired t-test, control (n = 20 cells) vs. RRS (n = 23 cells), from 2 to 3 slices per mouse and 8 mice per group. h mIPSCs comparison. Unpaired t-test, control vs. RRS, n = 31 cells per group (3–4 slices per mouse, 8 mice each group). All bar graphs represent mean ± SEM.

Since RRS reduced the excitatory synaptic drive of layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons in C57BL6 mice, we compared the synaptic activity of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons in Ghsr1a-shRNA-expressing mice with and without RRS exposure (Fig. 6e–h). Interestingly, layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons with GHS-R1a knockdown exhibited increased mEPSCs frequency 6 d post-RRS compared to unstressed controls (Fig. 6f, g; unpaired t-test, RRS vs. control, mEPSCs frequency: t = 3.23, **P < 0.01; mEPSCs amplitude: t = 0.27, P > 0.05). There was no significant difference in either mIPSCs amplitude or frequency (Fig. 6f, h; unpaired t-test, RRS vs. control, mIPSCs amplitude: t = 1.30, P > 0.05; mIPSCs frequency: t = 1.18, P > 0.05). Taken together, our findings consistently demonstrate that disrupting endogenous GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons reverses RRS-induced E/I imbalance and prevents the development of stress-induced anxiety-like behavior. In other words, we predict that RRS-induced upregulation of endogenous GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons contributes to enhanced anxiety.

Increasing GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons enhances anxiety-like behavior

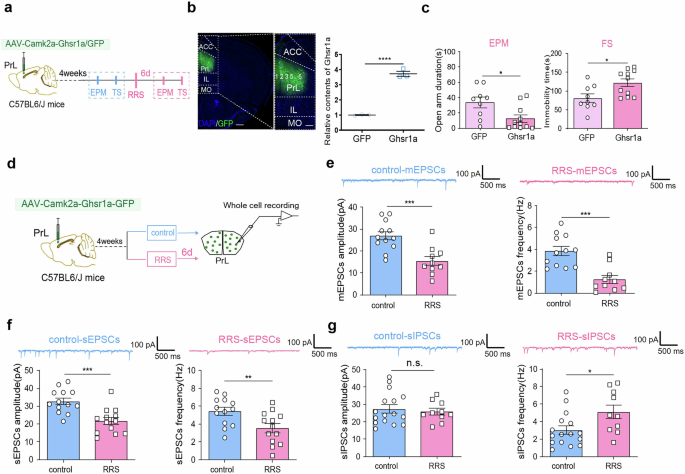

To increasing GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons, we administered AAV-Camk2a-hGhsr1a-GFP or control AAV-Camk2a-GFP to the PrL in C57BL6/J mice (Fig. 7a, b). RT-qPCR assays confirmed increasing Ghsr1a expression in the PrL region (Fig. 7b right; unpaired t-test, t = 16.09, ****P < 0.0001). Anxiety-related behavior was analyzed both under unstressed conditions and at 6 d post-RRS. Virus-mediated GHS-R1a overexpression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons did not affect anxiety-like behavior under baseline unstressed conditions (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, it did facilitate anxiety-related behavior in stressed mice. In particular, GHS-R1a-overexpressing mice spent less time exploring the open arms in the EPM test and more time immobile in the FS test than control mice expressing only GFP at 6 d after RRS exposure (Fig. 7c; unpaired t-test, GFP vs. Ghsr1a, EPM: t = 2.62, *P < 0.05; FS: t = 2.74, *P < 0.05). These findings confirmed that increasing GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons promotes vulnerability to RRS-induced anxiety.

a Experimental design. This figure was created using BioRender(https://www.biorender.com/). b Viral infection images and RT-qPCR assays. Left, Representative images illustrating viral infection in the PrL. Scale bar, left: 500 μm, right: 200 μm. Right, RT-qPCR assays of Ghsr1a expression in the PrL. Unpaired t-test, n = 3 mice per group. c EPM and FS tests conducted at 6 d after RRS exposure. Unpaired t-test, n = 9–11 mice per group. d Experimental design. This figure was created using BioRender(https://www.biorender.com/). e–g Comparison of synaptic activity in virus-infected PrLαCaMKII+ neurons with and without RRS exposure. e mEPSCs. control: n = 12 cells, RRS: n = 10 cells. f sEPSCs. n = 13 cells per group. g sIPSCs. control: n = 16 cells, RRS: n = 10 cells. Unpaired t-test, control vs. RRS, 2 – 3 slices per mouse from 5 to 6 mice per group. All bar graphs represent mean ± SEM.

We also compared the synaptic activity of GHS-R1a-overexpressing PrLαCaMKII+ neurons in mice with and without RRS exposure (Fig. 7d). Noticeably, layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons with GHS-R1a overexpression exhibited reduced mEPSCs (Fig. 7e; unpaired t-test, RRS vs. control, mEPSCs amplitude: t = 4.06, ***P < 0.001; mEPSCs frequency: t = 4.51, ***P < 0.001), reduced sEPSCs (Fig. 7f; unpaired t-test, RRS vs. control, sEPSCs amplitude: t = 4.11, ***P < 0.001; sEPSCs frequency: t = 2.86, **P < 0.01), and increased sIPSCs frequency (Fig. 7g; unpaired t-test, RRS vs. control, sIPSCs frequency: t = 2.46, *P < 0.05) at 6 d following RRS exposure. Therefore, we conclude that increasing GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons exacerbates RRS-induced E/I imbalance and enhances anxiety-like behavior.

As endogenous GHS-R1a expression in the BLA was not significantly elevated 6 d after RRS exposure, we investigated whether virus-mediated upregulation of GHS-R1a expression in BLAαCaMKII+ neurons affected anxiety-related behavior as a control. We found that virus-mediated GHS-R1a expression in BLAαCaMKII+ neurons did not affect anxiety-related behavior either under baseline conditions or after RRS (Supplementary Fig. 6). Taken together, our findings clearly demonstrated a causal relationship between GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons and anxiety-like behavior. We highlighted that RRS-induced delayed elevation of GHS-R1a expression contributes to an E/I imbalance in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons, leading to the development of enhanced anxiety-like behavior. GHS-R1a signaling in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons may be a potential treatment target for stress-induced anxiety disorders, such as PTSD.

Discussion

Current findings regarding the role of ghrelin and GHS-R1a in emotion processing or expression are contradictory34,35. We previously found that GHS-R1a knockout alleviated anxiety- and depression-related behaviors after CSDS14. In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that ghrelin restricts anxiety after acute stress35 and protects against depressive symptoms induced by chronic stress4. Therefore, ghrelin/GHS-R1a signaling may play distinct roles, either maladaptive or adaptive, in the development of anxiety or depression. However, the underlying mechanism is largely unknown.

In this study, we first demonstrated that mice exposed to RRS (1 h/d for 4 d) developed persistent anxiety-like behavior that matured at 6 d after stress exposure. Interestingly, we found that endogenous GHS-R1a expression in the mPFC was elevated at 6 d (but not at 90 min) after RRS exposure. Notably, Kuang et al. demonstrated that P2X2 expression in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons was upregulated 10 d after CSDS exposure32. The temporal association between the stress-induced increase in GHS-R1a expression in the mPFC and the development of enhanced anxiety-like behavior suggests that ghrelin/GHS-R1a signaling in the mPFC may promote vulnerability to stress-induced anxiety. By direct manipulation of GHS-R1a expression in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons, we confirmed that increasing GHS-R1a expression promoted anxiety-like behavior in stressed mice, while disrupting endogenous GHS-R1a expression in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons was necessary to reduce anxiety-like behavior in not only unstressed mice but also stressed ones. Our study thus revealed, for the first time, a causal relationship between ghrelin/GHS-R1a signaling in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons and stressed-induced enhancement of anxiety-related behavior.

Many studies have reported structural and/or functional changes in mPFC neurons associated with stress exposure in both rodents and human beings36,37. For instance, chronic stress exposure decreases spine density38,39,40 and promotes E/I synaptic imbalance in mPFC neurons21,23. Our study also demonstrated that RRS exposure reduced the excitatory synaptic drive of mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons and enhanced anxiety-like behavior in mice. Consistent with our findings, Kuang et al. reported that CSDS exposure decreased mEPSCs in mPFC neurons32. However, a recent study showed that increased mEPSCs in vmPFC neurons are associated with chronic pain-induced anxiety41. Currently, how mPFC neurons respond to stressful events and participate in the processing of anxiety-related behavior is not fully understood20.

We found via in vivo fiber photometry that the activity of mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons increased when mice initiated exploration of the more stressful open arms than the closed arms in the EPM, both under baseline conditions and after RRS exposure. Chemogenetic activation of mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons ameliorated anxiety-related behavior, further indicating that mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons play an anxiolytic role in response to stress and protect individuals against the development of stress-induced overanxiety. Consistent with our findings, a previous study showed that chemogenetic activation of mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons reduces anxiety-related behavior, while chemogenetic inactivation of mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons has the opposite effect42. In addition, studies have demonstrated that the optogenetic activation of mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons induces anxiolytic and antidepressant behaviors19, while photoinhibition of these neurons induces social avoidance43.

Moreover, our immunostaining assays revealed a decrease in c-Fos expression in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons at 6 d compared to unstressed or 90 min after RRS, which coincided with a delayed increase in GHS-R1a expression, a decreased excitatory synaptic drive in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons, and enhanced anxiety-like behavior in mice. More importantly, we demonstrated that increasing GHS-R1a expression in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons exacerbated RRS-induced E/I imbalance, and deletion of GHS-R1a expression in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons reversed RRS-induced E/I imbalance. Interestingly, in addition to decreased excitatory transmission, we observed increased inhibitory transmission in Ghsr1a-overexpressing mice following RRS exposure, even though our studies primarily focused on PrLαCaMKII+ neurons and specifically manipulated GHS-R1a expression in PrLαCaMKII+ excitatory neurons. Previously, we reported that GHS-R1a is expressed in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the hippocampus, where it plays opposite roles in regulating neuronal excitability and synaptic function44. Based on this, we propose that RRS exposure may alter GHS-R1a expression in mPFC inhibitory neurons, potentially leading to a direct increase in GABA release from interneurons that synapse onto PrLαCaMKII+ neurons. Supporting this hypothesis, we observed reduced inhibitory transmission in global GHS-R1a KO mice, but not in mice expressing Ghsr1a-RNAi specifically in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons. Alternatively, GHS-R1a upregulation in PrLαCaMKII+ neurons could enhance postsynaptic GABA_A receptor function through intracellular signaling pathways, thereby modifying GABAergic transmission. These direct and indirect mechanisms may work together to suppress the activity of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons, increasing the overall inhibitory tone in the PrL and potentially influencing emotional behaviors. Our findings therefore provide new insight into the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the involvement of ghrelin/GHS-R1a signaling in anxiety regulation.

In conclusion, the ghrelin/GHS-R1a signaling contributes to the development of vulnerability to stress-induced anxiety by shaping the activity of mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons. GHS-R1a in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons may be a new therapeutic target for treating anxiety disorders, such as PTSD.

Methods

Animal

Male adult C57BL/6 J mice (10-16 weeks old) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology. Ghsr1a KO mice (Ghsrtm1Smoc) were obtained Shanghai Research Center for Biomodel Organisms (by deleting the exon 1 and exon 2 of Ghsr1a gene (NCBI ID 208188) in C57BL/6 J background mice)45. Three to five mice pre-cage were fed in the environment with preference temperature (21 ± 2 °C) and humidity (50 ± 10%), free access to water and food, and 12 h:12 h light/dark cycle. All behavioral experiments were conducted using male adult mice (3-4 months old, weighing 25-30 g), during the light cycle (9:00 am to 6:00 am). The mice were acclimated in the laboratory for one week after purchase, with at least three days of acclimatization prior to experiment. Mice were randomly assigned to experimental or control groups with blockrandomization method. The total number of mice used for per experiment is detailed in the corresponding figure legend. The Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee at Qingdao University approved all animal protocols(#3207090367) used in this study, in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. All surgeries were performed under isoflurane anesthesia, with every effort made to minimize pain, suffering, and distress. After behavioral tests, mice were euthanized using intraperitoneal injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium, and brain samples were subsequently collected.

Repeated restraint stress (RRS)

A plexiglass cylindrical holder with front air holes and an adjustable backboard was used as the restraint device. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and quickly placed into the restrainer. The awake mice were then restrained from voluntary movement but could breathe freely in the holder for 1 h per day, and for consecutive 4 d. Mice returned to home cage after daily restraint.

Behavioral tests

Mice were habituated in the experimental environment for at least 1 h before behavioral tests, and all tests were done between 9:00 am and 6:00 pm. Feces and urine left by one mouse in testing chamber was cleaned up followed by 75% alcohol spray, so as not to affect behavior of following mouse. Animal behaviors were video-tracked and analyzed by two independent investigators with Noldus EthoVision XT software.

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) Test

The EPM is composed of five parts: one central area, two closed arms with walls (16.5 cm height), and two open arms without wall. Each arm is 30 cm long and 6 cm wide. The main frame is 50 cm high from the ground. Mice were released from the center and allowed to freely explore the maze for 10 min. To evaluate anxiety-like behavior, time spend in open and closed arms, number of arm entries, and total travel distance in the maze were analyzed. Behavioral analysis was conducted frame by frame using a custom MATLAB program.

Social interaction (SI) test

The experiment was carried out in a 40 cm × 40 cm × 25 cm chamber. Individual mouse was first allowed to freely explore the chamber for 5 min. It was then introduced to an unfamiliar, ovariectomized female mouse enclosed in the center of the test box. The social activity of the experimental mouse, i.e. sniffing the female mouse within close proximity (less than 1 cm), was recorded during the following 10 min.

Tail suspension (TS) test

During a test, mice were suspended upside down with tail being attached with medical tape to a horizontal iron lever located 60 cm above ground level. Immobility behavior defined as hanging passively without any voluntary movement except breath was analyzed for 10 min.

Forced swimming (FS) test

The FS test was used to evaluate despair-like behavior. During a test, mice were gently released into a transparent plastic cylinder (25 cm height ×10 cm diameter) filled with water (24.5 ± 0.5 °C) up to a depth of 15 cm. Total immobility time were analyzed during a 5 min-FS test.

Virus injection in the mPFC

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and head-fixed on a stereotaxic apparatus (RWD Life Science, China). Ophthalmic ointment (Chenxin, China) was applied to prevent dry eye. Body temperature was maintained at 37 °C with a heating pad. Virus was administrated through a glass needle connected to a Nanoliter 2000 microinjector (World Precision Instruments Inc., USA) at an injection rate of 60 nl/min. For fiber photometry recordings, 60 nl of AAV-Camk2a-GCaMP6f (Taitool Bioscience, Shanghai, China) virus was delivered unilaterally into the PrL. For chemogenetic activation of mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons, 250 nl of AAV-Camk2a-hm3dq-mCherry virus or control AAV-Camk2a-mCherry virus (OBiO, Shanghai, China) was bilaterally delivered into the PrL. For manipulation of GHS-R1a expression in mPFCαCaMKII+ neurons and BLAαCaMKII+ neurons, 200 nl of AAV-Camk2a-Ghsr1a-shRNA-GFP virus or control AAV-Camk2a-scramble-shRNA-GFP virus (Genechem, Shanghai, China), or AAV-Camk2a-Ghsr1a-GFP virus or control AAV-Camk2a-GFP virus (OBiO, Shanghai, China) was bilaterally delivered into the PrL, or BLA, respectively. The coordinates of PrL were ML ± 0.4 mm, AP + 1.8 mm, DV -2.0 mm relative to bregma. The coordinates of BLA were AP − 1.2 mm, ML ± 3.6 mm, DV − 5.2 mm relative to bregma. The optical fiber embedding site is usually 0.2 mm above the virus injection site.

In vivo Ca2+ Fiber photometry

A 200 μm diameter optical fiber (Inper, Hangzhou, China) was implanted into the layer 5/6 of PrL right after AAV-Camk2a-GCaMP6f virus delivery. Four weeks later, in vivo Ca2+ activity of the layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons was monitored using a fiber photometry (Thinker Tech, Nanjing Biotech Co., Ltd., China) during mice exploring the EPM. Mice were habituated to the system for 3 days before starting real experiment. Calcium signals of layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons were recorded both before (baseline) and after RRS exposure. The fluorescence signals were first subjected to unified denoising processing using MATLAB function “wden”, then normalized by (F– F0)/ F0, where F0 represents baseline fluorescence. The dF/F represents the real-time, active state of layer 5/6 PrLαCaMKII+ neurons as mice explore predefined areas (open or closed arms). The area under the curve (AUC) per second was calculated using the following equations: Fig. 3h (left and middle): AUCpre = ∑(dF/ Fpre)/2 s, AUC open or closed = ∑(dF/Fopen or closed)/6 s; Fig. 3h (right): AUC Total = (∑(dF/ Fopen) + ∑(dF/Fclosed) / (Timeopen + Timeclosed); Supplementary Fig. 3d: AUCopen or closes = ∑(dF/ F(x))/Time(x), where x refers to open arm or closed arm in the test. We used 6 s as the unit time for analysis based on a pre-calculation of the average open-arm duration per trail for all tested animals (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c).

DREADDs and CNO injection

The hM3Dq-DREADD is activated by clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) to enhance neuronal activity. CNO (Tocris, USA) was dissolved in DMSO as 5 mg/ml stock solution, which was diluted 500 times with normal saline (0.9%) for in vivo experiment, and 1500 time with ACSF for in ex vivo whole-cell patch clamp recordings. Specifically, mice received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of CNO (1 mg/kg of body weight) or same amount of 0.9% saline 45 min before behavioral experiments30.

Immunofluorescent staining

Mouse brain tissue was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and then transferred to 30% sucrose solution. Brain sections (40 µm thickness) were cut using a cryostat (Leica CM1950, USA). The primary antibodies used included rabbit anti-c-Fos antibody (1:3000, Cell Signaling Technology, #2250), mouse anti-αCaMKII antibody (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, #50049), and chicken anti-GFP antibody (1:1000, Invitrogen, PA1-9533). The secondary antibodies used were goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa 488 (1:500, Invitrogen, A-11008), goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa 568 (1:500, Invitrogen, A-11029), or goat anti-chicken IgG Alexa 488 (1:500, Invitrogen, A-21467). All antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (California, USA) and Invitrogen (Massachusetts, USA). Slices were counter-stained with 40, 60-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:1000 from Thermos Fisher Scientific, USA, #D3571). Fluorescence images were captured with a laser confocal microscope (Olympus FV500, JAPAN) equipped with Fluoview 2000 software. At least three representative coronal sections spaced equally along the AP axis were adopted for quantifications.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

The RNAscope kit V2 (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, USA) was used for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assays, following the same procedure described in our previous study30. Briefly, fresh brains were instantly frozen in isopentane. Brain slices (14 μm thickness) were fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min at 4 °C, and dehydrated sequentially in 50%, 70%, and 100% ethanol, RNA probes for Camk2a, Ghsr1a, and negative control probe were purchased from ACD. The main fluorescence dyes used were TSA Plus FITC, TSA Plus Cy3, and TSA Plus Cy5 (Akoya Biosciences, USA). Fluorescence images were captured with a Leica LAS-X confocal microscope with a 63× oil-immersion objective lens.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

PrL tissue was quickly isolated from ice-cold fresh brain slices (300 μm thickness) prepared using a vibratome (Leica VT1000, USA) and transferred into enzyme-free EP tubes pre-cooled on dry ice. Total RNA was extracted using the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quantity and quality were measured with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Single-stranded cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA). The reaction condition was as follows: 25 °C for 10 min, 50 °C for 30 min, 85 °C for 5 min. PCR-based quantification of Ghsr1a transcripts was performed using a Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System (Roche, USA) and QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen). The PCR cycling parameters were: 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of PCR reaction at 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min. PCR primer sequences (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were as follows: Ghsr1a-F GAAAATGCTGGCTGTAGTGGTG, Ghsr1a-R GACAAAGGACACGAG-GTTGC; Gapdh-F TGACGTGCCGCCTGGAGAAAC, Gapdh-R CCGGCATCGAAGGTGGAAGAG. 2−ΔΔCT method was used to normalize CT values against housekeeping gene Gapdh and to quantify relative expression of Ghsr1a. Triplicates were done for each sample.

mPFC slices preparation and electrophysiological recordings

Coronal mPFC slices (300 μm in thickness) were prepared using a Leica VT-1000 vibratome according to our previous studies46. Oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2), ice-cold cutting solution (pH 7.4) containing 2.5 mM KCl, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 7 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 30 mM Glucose, 119 mM Choline chloride, 3 mM Sodium pyruvate, 1 mM Kynurenic acid, and 1.3 mM sodium L-ascorbate. Slices were quickly transferred to recovery solution containing 85 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 4 mM MgCl2, 24 mM NaHCO3, 25 mM glucose, and 50 sucrose to recover for 30 min at 32 °C, and then for at least 1 h at room temperature before recording. Slices were transferred to the submerged recording chamber and continuously perfused with 32 °C artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing 120 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.3 mM MgSO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM glucose.

Firing of PrLαCaMKII+ neurons were measured with both whole-cell voltage-clamp and current-clamp recordings. Glass electrodes (4–6 MΩ) were pulled by a micropipette puller (P-1000, Sutter instrument). Whole-cell recording electrodes were filled with an internal solution containing 125 mM potassium gluconate, 20 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ATP, and 1 mM EGTA (pH 7.3-7.4, 285-295 mOsm). Only neurons with a resting membrane potential smaller than −55 mV were included in data analyses. Data were acquired using digidata 1440 A and pCLAMP 10.0 software (Molecular Devices, USA) with a sampling rate of 10 kHz30.

Spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) were isolated with 3 mM kynuric acid at a holding potential of +20 mV. Spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) were recorded at a holding potential of −70 mV with the presence of 50 μM AP-5 and 50 μM picrotoxin. Miniature excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs and mIPSCs) were recorded at the presence of 1 μM TTX. Only whole-cell recordings with series resistance changes less than 20% throughout the experiment were analyzed using Minis Analysis Program. Event counting was carried out by an experimenter blind to genotypes of mice. Data were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz with Digidata 1440 A and Clampex10. All chemicals used in electrophysiological recordings were purchased from Sigma.

Statistics and reproducibility

Data were expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. All experiments and data analyses were conducted in a blinded manner, with investigators unaware of the genotype or experimental manipulation. Sample size, ANOVAs or t-tests used for statistical comparisons between groups were described in main text or figure legends. Sample sizes were determined based on prior studies conducted in the lab. Normal distributions and equal variances were assured before performing parametric statistical analyses. Multiple comparisons were done as recommended by the software. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05 indicate a significant difference, n.s. means no significant difference.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses