An anti-Hebbian model for binocular visual plasticity and its attentional modulation

Introduction

Binocular vision is a fundamental process that merges visual information from both eyes into a unified stereoscopic perception1,2. A key mechanism underlying binocular integration is interocular suppression, which mediates a non-linear combination of binocular inputs, resulting in weaker binocular perception than the linear sum of monocular perceptions3. When the inputs from each eye sufficiently differ, interocular suppression leads to binocular rivalry, wherein subjective perception alternates randomly between the two inputs4. Interocular suppression occurs as early as the monocular stage in the primary visual cortex (V1). Many monocular neurons in the primate V1 exhibit reduced responses to binocular input compared to input from the dominant eye alone, suggesting that input from the non-dominant eye inhibits the activity of monocular neurons5,6.

Binocular vision exhibits plasticity, with ocular dominance adapting to binocular visual experience7. In animals, depriving one eye of visual input for several months during the visual critical period induces profound morphological changes, including shrinkage of cortical areas and ocular dominance columns associated with the deprived eye8,9,10,11, as well as reductions in axons, dendrites, and synaptic connections of neurons linked to the deprived eye11,12,13. These structural modifications are accompanied by functional alterations, including reduced neural responses9,13,14,15, permanent deficits in the visual acuity and contrast sensitivity of the deprived eye11,13,16,17, and loss of stereopsis17,18,19. Importantly, these cortical structural changes and the associated visual impairments resulting from long-term monocular deprivation do not occur in adulthood20, supporting the traditional view that the adult visual cortex is largely hardwired and exhibits limited plasticity21.

However, recent studies have revealed contrasting phenomena in adults following short-term monocular deprivation. Briefly patching one eye for durations ranging from tens of minutes to a few hours can enhance the subsequent ocular dominance of the deprived eye in binocular rivalry or combination tasks22,23,24,25. This increased dominance of the deprived eye is also reflected in neural signals, with V1 showing heightened responses to inputs from the deprived eye and reduced responses to inputs from the non-deprived eye26,27,28. Unlike long-term deprivation, short-term monocular deprivation does not seem to induce lasting morphological changes, as its effects typically fade approximately within 15 to 90 min22,24,25,26. This counter-intuitive effect may reflect homeostatic plasticity, whereby visual cortical activity during deprivation remains relatively stable through increased gain for the deprived eye, decreased gain for the non-deprived eye, or a combination of both adjustments22,29.

The mechanism underlying short-term monocular deprivation remains unclear, although it has been speculated that inhibitory interactions between the two eyes play an important role28,30,31. Interestingly, binocular rivalry—a perceptual phenomenon resulting from interocular suppression—also exhibits plasticity. During prolonged binocular rivalry, the proportion of exclusive percepts decreases while that of mixed percepts increases32,33,34. Plasticity in the interocular inhibitory synapses may underpin this phenomenon34. We hypothesized that these various forms of binocular plasticity share a common origin, with interocular suppression serving as the critical process.

The influence of cognitive factors on short-term monocular deprivation is also an intriguing question35,36,37. Attention, as a fundamental cognitive process that selectively prioritizes relevant information, is a key prerequisite for learning38,39, such as motor skill acquisition40 and language learning41. However, perceptual learning, which relies on plasticity in the sensory cortex, can occur without attention42,43,44,45. It is conceivable that binocular visual plasticity, a form of plasticity originating in the early visual cortex, may occur independent of attention. Although several studies have suggested that attention may enhance short-term monocular deprivation effect35,37,46, no studies have directly investigated whether this deprivation effect requires attention.

Here, through a combination of psychophysical experiments and computational modeling, we explored how attention modulates short-term monocular deprivation and developed a neural computational model to uncover the mechanisms underlying this and other forms of binocular plasticity. In the psychophysical experiment, we examined monocular deprivation effects under conditions in which attention was either focused on or withdrawn from the localized monocular stimuli. The results showed that the deprivation effect was dramatically diminished when attention was removed. In the computational modeling, based on a previous binocular rivalry model47, we introduced a Hebbian learning rule at the inhibitory synapse of opponency neurons47,48, termed anti-Hebbian learning34,49, to simulate the effects of short-term monocular deprivation. Our model accurately predicted the deprivation effect and its dependence on attention, and simulated other forms of binocular plasticity, such as plasticity in prolonged binocular rivalry. We propose that the plasticity in inhibitory connections between the two monocular pathways is fundamental to short-term binocular plasticity.

Results

Psychophysics: Attention modulates monocular deprivation effects

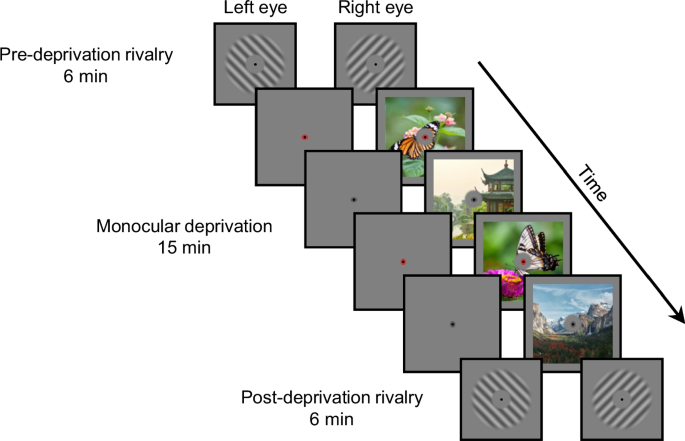

Monocular deprivation was implemented using a novel approach—monocular flash deprivation—derived from continuous flash suppression50 (Fig. 1). During the 15-min monocular deprivation, a rapid sequence of colorful outdoor scenes was presented to the non-deprived eye, while a blank screen to the deprived eye. Concurrently, a series of ellipses dynamically altering in orientation (vertical or horizontal) and color (red or gray) were presented in the fovea of both eyes. The deprivation phase involved three levels of attention: fixation, unattended, and attended. In the fixation condition, observers maintained their fixation on the central point and ellipses, passively observing scene images in the parafovea. In the unattended condition, observers continuously engaged in a demanding color-shape conjunction detection task in the fovea51, which forced them to disregard monocular scene images. In the attended condition, observers diligently focused attention on monocular images, detecting randomly inserted butterfly images within the scene sequence50. Ocular dominance was evaluated before and immediately after deprivation during the 6-min pre- and post-deprivation binocular rivalry phases.

During the pre- and post-deprivation rivalry phases, observers continuously reported which grating they perceived exclusively by continuously pressing the corresponding key. During the monocular deprivation phase, observers’ one eye viewed a rapid sequence of colorful outdoor scenes alternating at 10 Hz while the other eye viewed a blank screen. Concurrently, a series of ellipses with orientation and color changing continually at 1 Hz were displayed in the fovea of both eyes. In the fixation condition, observers maintained fixation on the central point and ellipses and passively observing scene images in the parafovea. In the unattended condition, observers continuously performed a demanding color-shape conjunction detection task in the fovea. In the attended condition, observers diligently focused attention on the monocular images and detected butterfly images that were randomly inserted into the sequence of scene images. The natural images are replotted with permission from Unsplash135.

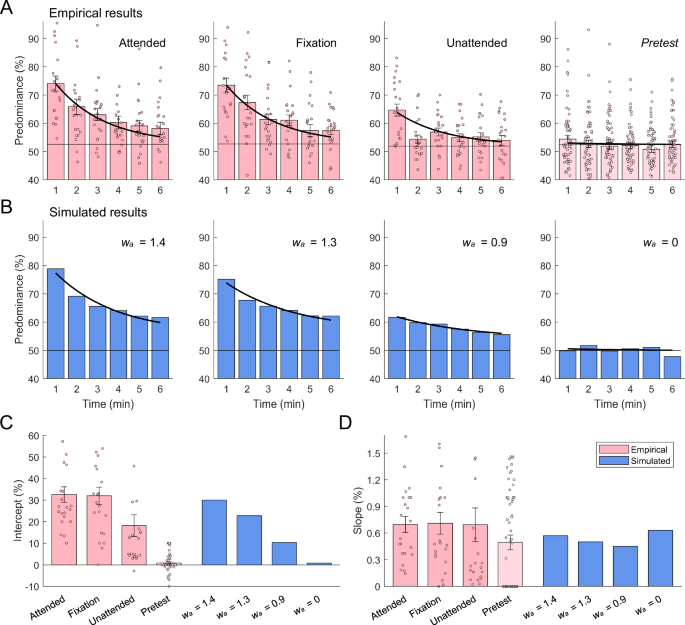

The monocular deprivation effect refers to the changes in ocular dominance following monocular deprivation22,23. In this study, we measured this effect using two indicators during the pre- and post-deprivation binocular rivalry phases: the predominance of the deprived eye and the normalized mean dominance duration for both eyes50. The predominance of the deprived eye was defined as the total exclusive viewing time of the deprived eye divided by the total exclusive viewing time of both eyes (excluding mixed percepts) in binocular rivalry. Each 6-min rivalry phase was divided into six 1-min windows. Predominance of the deprived eye was highest during the first min after deprivation and gradually returned to baseline in all attention conditions (Fig. 2A; two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Ftime(5,105) = 40.87, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.661). Notably, the magnitude of the deprivation effect varied across different attention conditions, with weaker attention on monocular stimuli resulting in smaller deprivation effect (Fattention(2,42) = 12.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.377). The interaction between attention condition and time was significant (Fattention×time(10,210) = 2.84, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.119). Post hoc tests revealed that in the attended and fixation conditions, the predominance of the deprived eye in the first min was significantly higher than in other time bins (ps < 0.005, Bonferroni corrected), exhibiting a large and rapid decline. However, in the unattended condition, the predominance in the first min was only higher than that in the second min (p < 0.001, Bonferroni corrected), showing a smaller decline.

A Empirical results (n = 22). Each 6-min rivalry phase was divided into six 1-min windows and the predominance of the deprived eye for each 1-min window was defined as the total exclusive viewing time of the deprived eye divided by the total exclusive viewing time of both eyes. Left three panels depict the predominance of the deprived eye in post-deprivation rivalry periods for three attention conditions, and the rightmost panel depicts the results in pre-deprivation rivalry periods for all conditions. Black horizontal lines show the baselines, computed as the mean predominance of the to-be-deprived eye in the pre-deprivation rivalry periods. Thick black curves show the fitting functions with non-linear regression model. Pink dots show individual data. Error bars denote 1 SEM. B Simulated results. From left to right are the results of post-deprivation rivalry periods with attention weights in monocular deprivation decreasing, and the rightmost panel depicts the results from monocular deprivation where attention weight equaled 0. Black horizontal lines show the baselines, computed as the mean predominance of the to-be-deprived eye in the pre-deprivation rivalry periods, and the pre-deprivation rivalry periods were simulated by setting inhibition weights at an initial value of 0.65. Thick black curves show the fitting functions with non-linear regression model. C Intercept parameter estimates of non-linear regression model. Pink bars depict parameters fitted from psychophysical data, and blue bars depict parameters fitted from simulated data. Error bars denote 1 SEM. D Slope parameter estimates of non-linear regression model. Legends are the same as above.

To evaluate the recovery of interocular balance following deprivation, we employed an exponential function to fit the deprivation effects in predominance. The two free parameters, intercept and slope, indicate the initial amount of shift and the decay rate of predominance, respectively50. The model exhibited a good fit across conditions (Fig. 2A, thick black curves). Significant variation in the intercept was observed across conditions (Fig. 2C, pink bars; one-way ANOVA, F(3,36) = 46.0, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.503). Specifically, the intercept was notably higher in the attended and fixation conditions than in the pretest condition (ps < 0.001, Games-Howell test), while moderate significance was observed between the unattended and pretest conditions (p = 0.012, Games-Howell test). In contrast, the slope was not significantly different across conditions (Fig. 2D, pink bars; F(3,50.6) = 1.22, p = 0.313, η2 = 0.024).

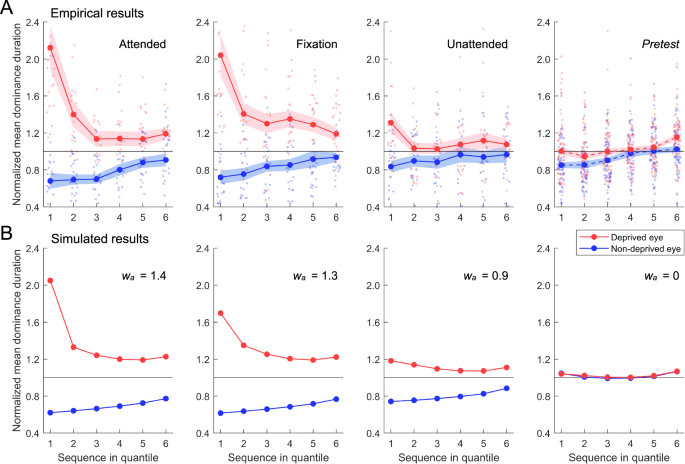

Changing trends over time quantiles were also assessed for normalized dominance duration, which was computed by dividing each dominance duration by the mean dominance duration measured during the pretest50. The deprived eye initially exhibited a significant advantage in dominance durations, but this advantage decreased rapidly over time (Fig. 3A, red curves; two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Ftime(5,100) = 19.54, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.494). A significant main effect of attention was observed (Fattention(2,40) = 5.41, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.213), with the mean dominance duration of the deprived eye decreasing as attention weakened. A significant interaction between attention and time was also observed (Fattention×time(10,200) = 3.83, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.161). Post hoc tests indicated that in the attended and fixation conditions, the normalized mean dominance duration of the deprived eye was significantly greater only in the first quantile (ps < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected), indicating a significant but short-lived effect of deprivation. In the unattended condition, no significant difference was observed across quantiles (ps = 1.00, Bonferroni corrected), indicating that the deprived eye did not show a significant deprivation effect.

A Empirical results (n = 22). Dominance durations represent the length of continuously exclusive perception of a rival stimulus, as indicated by observers’ key presses. Normalized dominance durations were computed by dividing each dominance duration by the mean dominance duration measured from pre-deprivation rivalry periods. Sequences of normalized dominance durations of every observer were divided into six quantiles, and for each quantile, the mean dominance durations were computed and averaged over observers. Left three panels depict the time-ordered quantile plots of normalized mean dominance duration in post-deprivation rivalry periods for three attention conditions, and the rightmost panel depicts the results in pre-deprivation rivalry periods for all conditions. Red and blue curves represent the normalized mean dominance durations for the deprived and non-deprived eye, respectively. Red and blue dots show individual data for the deprived and non-deprived eye, respectively. Shaded regions denote 1 SEM. B Simulated results from the model incorporating both anti-Hebbian learning and time-dependent changes of short-term adaptation. From left to right are the results of post-deprivation rivalry periods with attention weights in monocular deprivation decreasing, and the rightmost panel depicts the results from monocular deprivation where attention weight equaled 0.

The non-deprived eye showed a gradual rise in dominance durations (Fig. 3A, blue curves; two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Ftime(5,100) = 9.15, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.314), indicating a slow decline of deprivation effect. Across attention conditions, the normalized mean dominance duration increased with the weakening of attention in deprivation (Fattention(2,40) = 3.20, p = 0.052, ηp2 = 0.138), indicating attentional modulation of deprivation effect in the non-deprived eye. The interaction between attention condition and time was not significant (Fattention×time(10,200) = 0.41, p = 0.943, ηp2 = 0.020).

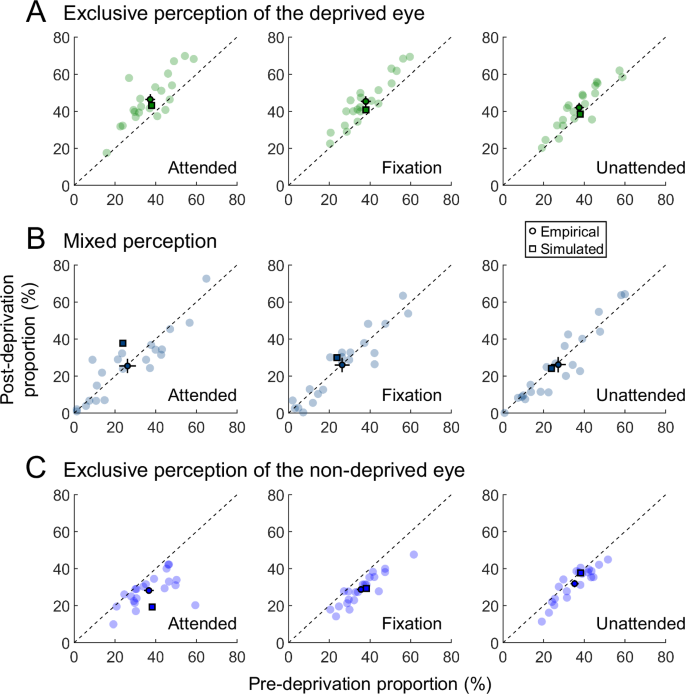

We also analyzed the changes in exclusive and mixed perception induced by monocular deprivation under different attention conditions. After deprivation, the proportion of exclusive perception increased significantly for the deprived eye, while it decreased significantly for the non-deprived eye (Fig. 4A and C; two-way repeated measures ANOVA, the deprived eye, Fpre-post(1,20) = 63.11, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.759; the non-deprived eye, Fpre-post(1,20) = 37.51, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.652). Both eyes exhibited an interaction between attention and deprivation (the deprived eye, Fattention(2,40) = 2.84, p = 0.071, ηp2 = 0.124, Fattention×pre-post(2,40) = 4.17, p = 0.023, ηp2 = 0.173; the non-deprived eye, Fattention(2,40) = 1.12, p = 0.335, ηp2 = 0.053, Fattention×pre-post(2,40) = 6.17, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.236). However, the proportion of mixed perception did not show significant differences between pre- and post-deprivation rivalry across different attention conditions (Fig. 4B; Fpre-post(1,20) = 0.42, p = 0.524, ηp2 = 0.021; Fattention(2,40) = 0.16, p = 0.850, ηp2 = 0.008; Fattention×pre-post(2,40) = 0.07, p = 0.929, ηp2 = 0.004).

A The post-deprivation proportion of exclusive perception for the deprived eye plotted against the pre-deprivation proportion (n = 21). Light-colored dots show individual data, dark-colored dots indicate the mean empirical data, and squares represent the simulated data. Error bars represent 1 SEM. B The post-deprivation proportion of mixed perception plotted against the pre-deprivation proportion. C The post-deprivation proportion of exclusive perception for the non-deprived eye plotted against the pre-deprivation proportion.

In our experiment, ellipses in the fixation task were presented binocularly. These foveal binocular stimuli may have interrupted monocular deprivation in the parafoveal region, potentially contributing to a reduced deprivation effect, particularly when attention was focused on them (i.e., in the unattended condition). However, in a supplementary experiment in which the foveal ellipses in the deprived eye were removed, highly similar results were observed (Supplementary Fig. 6; see Supplementary Information: Supplementary Experiment for details). Collectively, these findings suggest that the enhancement of ocular dominance for the deprived eye following short-term monocular deprivation strongly depends on attention. We further investigated the potential mechanisms underlying these effects in the subsequent modeling section.

Computational modeling: An anti-Hebbian model for binocular plasticity and its attentional modulation

Binocular rivalry evolves over time, characterized by a decrease in exclusive percepts and an increase in mixed percepts32,33,34. This phenomenon of binocular plasticity was assumed to arise from weakened interocular suppression, possibly mediated by Hebbian learning at interocular inhibitory synapses connecting neurons from each eye34,52. During rivalry, perception alternates between the stimuli presented to each eye, and the neural responses corresponding to the predominant eye at any given moment are stronger than those of the non-predominant eye. This asynchronous activity of neurons corresponding to the two eyes promotes inhibitory synaptic learning, termed as anti-Hebbian learning53,54, weakening the inhibitory connections from the predominant to the non-predominant eye. Similarly, monocular deprivation creates an imbalance in binocular inputs, which should also lead to the depression of interocular inhibitory connections and, consequently, a reduction in interocular suppression. Thus, the anti-Hebbian learning rule may underlie short-term monocular deprivation.

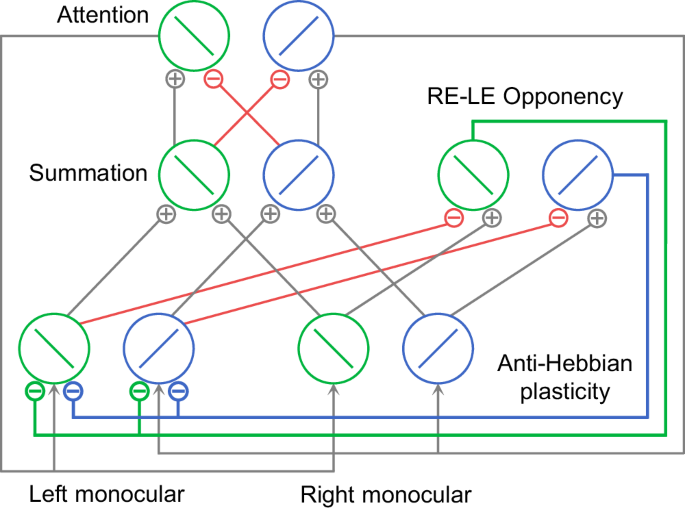

Li et al.47 developed a model that simulated both perception switching and attentional modulation in binocular rivalry. However, their model assumes static neural connection weights and therefore does not predict the plasticity observed in binocular rivalry. In contrast, our model incorporated a learning rule specifically for interocular inhibitory synaptic connections, enabling it to capture both binocular rivalry plasticity and various short-term binocular plasticity phenomena. Similar to Li et al.47, our model comprises four types of neurons: monocular, opponency, binocular summation, and attention neurons (Fig. 5; see Methods for mathematical details). Interocular suppression is mediated by inhibitory connections from opponency neurons to contralateral monocular neurons, and attentional modulation is achieved through gain control from attention neurons to monocular neurons. Crucially, anti-Hebbian learning is applied to the inhibitory synapses that link opponency neurons to contralateral monocular neurons (Fig. 5, thick lines).

The model structure is adapted with permission from Li et al.47. Each binocular summation neuron receives excitatory inputs from monocular neurons that are selective for the same orientation. Each attention neuron receives excitatory inputs from the binocular summation neuron that is selective for the same orientation, and suppressive inputs for different orientation. Monocular neurons selective for the same orientation receive the same attention gain factor determined by the response of the attention neuron with the same orientation preference. Opponency neurons compute the response difference between two eyes for a particular orientation and send inhibition to monocular neurons of contralateral eye. The anti-Hebbian plasticity is applied to synapses between opponency neurons and contralateral monocular neurons (thick lines). Green and blue circles represent neurons selective for two orientations, −45° and +45° from vertical, respectively. Green and blue lines represent inhibitory connections from opponency neurons selective for the two orientations (−45° and +45° from vertical) to monocular neurons in contralateral eye. Red lines represent other inhibitory connections. Gray lines represent excitatory connections and attentional modulation. Only the right-minus-left (RE-LE) opponency neurons are illustrated.

During binocular rivalry or monocular deprivation, owing to the competition between eyes or the deprivation of one eye, only one eye’s input is perceived at any given moment. This predominant eye elicits strong activity in associated neurons, including opponency neurons that receive the difference between the eyes as input. Given the low activity of contralateral monocular neurons driven by the non-predominant eye, anti-Hebbian learning leads to a reduction in inhibition weights (w_{o}) from the opponency neurons of the predominant eye onto contralateral monocular neurons over time, owing to the asynchrony of pre- and postsynaptic activity. This reduction in inhibition weights occurs only when the activity of opponency neurons reaches a presynaptic threshold. Consequently, the interocular suppression onto the non-predominant eye gradually diminishes, whereas the suppression onto the predominant eye remains unchanged.

In the following modeling results, we first simulated the dynamics of monocular deprivation under different attention conditions and examined the resulting inhibitory changes. The attention level in the model was manipulated by adjusting the attention weight (w_{a}), with higher values representing stronger attention. Next, based on the inhibitory changes induced by monocular deprivation across different attention conditions, we simulated subsequent post-deprivation rivalry dynamics, including alterations in ocular dominance and shifts in exclusive and mixed perception. Third, we simulated the dynamics of prolonged binocular rivalry under different attention conditions and analyzed the associated inhibitory changes and shifts in exclusive perception. Finally, we simulated a recently reported eye-based attention effect on ocular dominance plasticity35,37. Note that neural noise was not included in any simulation.

The anti-Hebbian model exhibits reduced inhibition onto the deprived eye and attentional modulation during monocular deprivation

To investigate whether anti-Hebbian learning accounts for the monocular deprivation effect and its dependence on attention, we simulated neural responses in monocular deprivation under different attention conditions. We designated the left eye as the deprived eye with no stimuli, whereas the right eye, the non-deprived eye, received orthogonal gratings swapped at 2 Hz (Fig. 6A). This setup matched the psychophysical experiment and allowed for analytical simplification (see Methods for details). The model parameters used in simulations are listed in Table 1. During deprivation, binocular summation neurons exhibited an alternating response pattern mirroring the frequency of stimuli in the non-deprived eye (Fig. 6C, top and middle panels), consistent with observers’ perceptual experience.

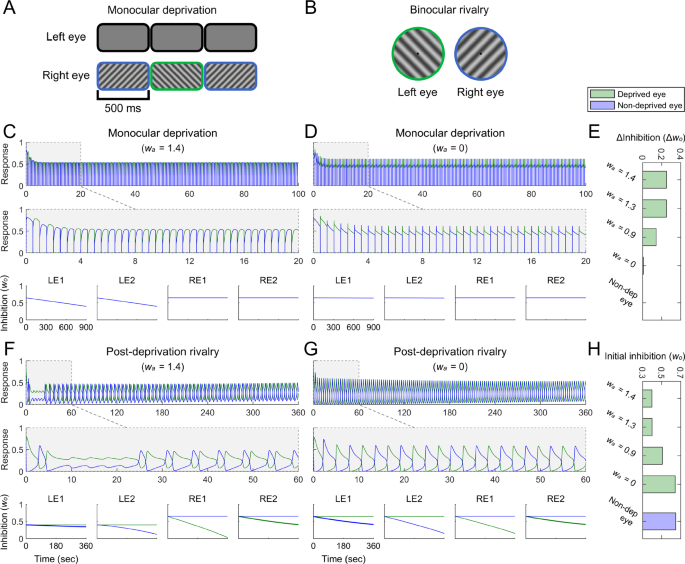

A Stimuli in monocular deprivation simulations. The left eye was designated as the deprived eye and received no stimuli, while the right eye was designated as the non-deprived eye and received orthogonal gratings swapped at 2 Hz. B Dichoptic gratings in binocular rivalry simulations. C The simulated responses of two binocular summation neurons in the first 100 and 20 s of monocular deprivation in the attended condition ((w_{a}) = 1.4, upper and middle panels), and the simulated changes of inhibition weights (w_{o}) (lower panel). LE1, LE2 represent left monocular neurons selective for two orientations, −45° and +45° from vertical, respectively. RE1, RE2 represent right monocular neurons selective for the two orientations. In simulated responses of binocular summation neurons, green and blue curves represent simulated responses of binocular summation neurons selective for −45° and +45°, respectively. In simulated changes of inhibition weights, green and blue curves represent inhibition weights from opponency neurons selective for −45° and +45°, respectively; these curves overlap because the inhibition weights onto the same neuron have the same changes in monocular deprivation. D Simulated responses of binocular summation neurons, and changes of inhibition weights during monocular deprivation in the unattended condition ((w_{a}) = 0). E Decrements of inhibition weights ((Delta w_{o}=w_{o}^{pre{mbox{-}}deprivation}-w_{o}^{post{mbox{-}}deprivation})) during monocular deprivation under different attention conditions, corresponding to the simulated deprivation effects shown in Figs. 2B and 3B. Green bars indicate inhibition weight decrements for the deprived eye, and the blue bar indicate those for the non-deprived eye. Because the inhibition weight decrements for the non-deprived eye are equal to 0, the blue bar is not visible. F Simulated responses of binocular summation neurons, and changes of inhibition weights during post-deprivation rivalry in the attended condition ((w_{a}) = 1.4, corresponding to the leftmost panels in Figs. 2B and 3B). The significance of curves aligns with that described in (C). In the simulated changes of inhibition weights, the LE1 bold blue curve and the RE2 bold green curve represent the inhibitory changes between stimulated monocular neurons in each eye during rivalry, which are associated with behavioral outcomes. G Simulated responses of binocular summation neurons, and changes of inhibition weights during post-deprivation rivalry in the unattended condition ((w_{a}) = 0). H Initial values of inhibition weights in post-deprivation rivalry under different attention conditions. Green bars indicate initial inhibition weights for the deprived eye, and the blue bar indicate those for the non-deprived eye.

The inhibition weights onto the deprived eye decreased over the course of deprivation owing to anti-Hebbian learning, whereas those onto the non-deprived eye remained constant (Fig. 6C, bottom panels). This aligns with previous experimental findings showing that short-term monocular deprivation selectively reduces interocular suppression for the deprived eye, without affecting suppression of the non-deprived eye30,31. Intriguingly, the decay rate of inhibition weights depended on attention; inhibition decreased more slowly when attention was partially diverted from monocular stimuli and remained nearly unchanged in the absence of attention (Fig. 6C–E; also see Supplementary Fig. 1). This is because attention boosted monocular neuron activity of the non-deprived eye, which in turn increased the response of corresponding opponency neurons and facilitated anti-Hebbian learning at inhibitory synapses connecting the non-deprived to the deprived eye. In contrast, the absence of attention reduced the activity of opponency neurons to a level insufficient to drive anti-Hebbian learning, leaving the inhibitory connections unchanged during the course of deprivation. These simulation results suggest the potential role of anti-Hebbian learning in mediating short-term monocular deprivation and underscore the critical role of attention in the formation of this plasticity.

In our model, attention influences monocular deprivation by modulating the gain of monocular neurons, functioning similarly to altering stimulus strength47,55,56. In fact, if the stimulus contrast of the non-deprived eye is reduced during monocular deprivation (Supplementary Fig. 2), the reduction in inhibition for the deprived eye is also diminished, mirroring a pattern akin to attentional modulation (Supplementary Fig. 2E–F).

In the experimental results, the effects of deprivation were typically reflected in changes in task performance (e.g., binocular rivalry) after deprivation. To test our model, we simulated the influence of monocular deprivation on binocular rivalry in the following section.

The anti-Hebbian model replicates the ocular dominance changes in binocular rivalry and the attentional effects following deprivation

In our model, monocular deprivation led to changes in inhibition weights, which resulted in an alteration of ocular dominance following deprivation. To simulate the effects of deprivation on binocular rivalry, the final values of inhibition weights after 15 min of deprivation were used as initial values for subsequent binocular rivalry simulations (Fig. 6H). The dynamics of perceptual switching during binocular rivalry were modeled using fluctuations in the activity of binocular summation neurons47. Consistent with observers’ reports, the dominance durations were notably extended for binocular summation neurons selective for the stimulus of the deprived eye (Fig. 6F, middle panel, green curve), reflecting prolonged perceptual durations and enhanced predominance of the deprived eye. Further, the deprivation effect showed a strong dependence on attention (Fig. 6F–G; also see Supplementary Fig. 3). When attention on monocular stimuli was strong, the deprived eye achieved complete dominance in the initial tens of seconds of subsequent binocular rivalry (Fig. 6F), aligning with observers’ reports of the immediate and overwhelming dominance of the deprived eye at the beginning of post-deprivation rivalry. This winner-take-all state arises from the inhibition imbalance between the two eyes at the onset of rivalry. The absolute dominance of the deprived eye quickly diminished as the inhibition onto the non-deprived eye rapidly decreased owing to its non-dominance in the rivalry. In contrast, when attention was diverted, the enhancement in the dominance for the deprived eye was reduced and even disappeared under no-attention conditions (Fig. 6G; also see Supplementary Fig. 3). These results closely mirror our experimental observations.

To evaluate the simulated deprivation effects, we performed a quantitative analysis for the fluctuations in the activity of binocular summation neurons. The predominance of the deprived eye (Fig. 2B) and the normalized mean dominance duration (Fig. 3B) were computed for each simulation condition using procedures identical to those used in the psychophysical experiment. Consistent with our psychophysical findings, the predominance of the deprived eye was strongest in the first min after deprivation and gradually returned to baseline, with the deprivation effect diminishing as attention decreased (Fig. 2B). The time-dependent decay of deprivation effect fit well with the same non-linear regression model used in our psychophysical experiment (Fig. 2B, thick black curve). The intercept decreased with lower attention levels (Fig. 2C, blue bars), whereas the slope exhibited no substantial variation across attention conditions (Fig. 2D, blue bars). Our model also accurately simulated the deprivation effect on dominance durations (Fig. 3B). In the high attention condition, the normalized mean dominance duration of the deprived eye increased greatly immediately after deprivation, followed by a rapid decline. As attention weakened, the deprivation effect decreased, and the initial advantage of the deprived eye became negligible under low or no attention conditions (Fig. 3B, red curves). Conversely, deprivation had an opposing effect on the dominance durations of the non-deprived eye, with attention exerting a similar modulatory influence (Fig. 3B, blue curves). These simulation results closely matched the trends observed in our psychophysical data (Fig. 3A).

It is important to note that our simulation of the empirical deprivation effects incorporated a process of time-dependent changes for short-term adaptation in monocular neurons. This process was modeled by gradually weakening the strength of short-term adaptation as time progressed (see Methods for details), which attenuated the recovery of suppressed neurons from adaptation57. Consequently, suppressed neurons had greater difficulty in overcoming the inhibition from dominant neurons and initiating a perceptual switch. This mechanism is crucial for simulating the upward trend in dominance durations observed for both eyes toward the end of the rivalry period (Fig. 3; see Supplementary Information: Time-dependent Changes of Short-term Adaptation for more information).

To quantify the shifts in exclusive and mixed perception induced by monocular deprivation, we computed an index simulating dynamic perception switches during the binocular rivalry simulation period48. This index (P(t)) was defined as the difference between the responses of binocular summation neurons selective for orthogonal orientations, divided by their summed responses (see Methods for details). We computed the proportion of exclusive perception for both eyes and the proportion of mixed perception during post-deprivation rivalry under different attention conditions and compared them with baseline proportions during pre-deprivation rivalry (Fig. 4, squares). The simulation results revealed that monocular deprivation increased exclusive perception for the deprived eye and decreased exclusive perception for the non-deprived eye, with these effects diminishing as attention was reduced (Fig. 4A and C). These findings align well with our psychophysical results and a previous study investigating the influence of monocular deprivation on binocular fusion58.

However, the simulation indicated an increased proportion of mixed perception whereas our psychophysical results showed no significant effect of monocular deprivation on mixed perception (Fig. 4B). This discrepancy likely arises from the differences in how mixed perception was computed in the simulation versus how it was reported in our psychophysical experiment. In the simulation, mixed perception included both balanced mixed perception and imbalanced mixed perception biased toward either the deprived or the non-deprived eye. Monocular deprivation primarily increased imbalanced mixed perception biased toward the deprived eye, leading to an overall increase in mixed perception in the simulation58. By contrast, observers in our experiment were not provided the option to report mixed perception biased toward one eye. Consequently, they likely applied strict criteria for identifying mixed perception, recognizing it only when there was a balanced mixed perception. Since balanced mixed perception was unaffected by monocular deprivation58, this may explain the absence of a significant effect in our psychophysical results.

The anti-Hebbian model shows reduced interocular inhibition and declined exclusive percepts in binocular rivalry

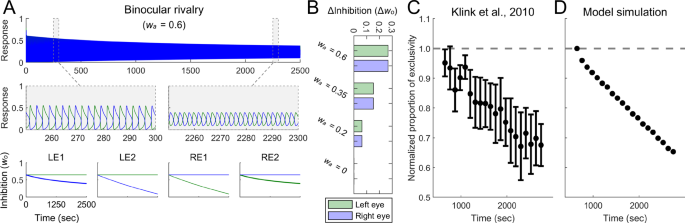

To evaluate the generalizability of our model, we simulated a prolonged binocular rivalry process to determine whether it could manifest the plasticity observed in prolonged binocular rivalry experiments32,34. For this simulation, the stimuli were two stationary orthogonal gratings (Fig. 6B). The results showed a progressive degradation in the alternation of neural responses to competing stimuli, indicated by a narrowing amplitude difference over time (Fig. 7A; also see Supplementary Figs. 4–5 for a comparison with Li et al.’s model47). This pattern aligns with experimental observations that perceptual alternations in binocular rivalry become less distinct over time, accompanied by an increase in mixed percepts, reflecting experience-driven plasticity in binocular vision32,34 (Fig. 7C). We used the index (P(t)) to quantify the shifts in mixed and exclusive percepts during simulation, with (P(t)) > 0.4 indicating exclusive percepts48. Consistent with psychophysical data, the proportion of exclusive percepts exhibited a gradual decline (Fig. 7D).

A The simulated responses of two binocular summation neurons during the entire 2500 s of binocular rivalry, as well as during the intervals 250–300 s and 2250–2300 s, in the attended condition ((w_{a}) = 0.6, upper and middle panels), and the simulated changes of inhibition weights (w_{o}) (lower panel). The significance of curves aligns with that described in Fig. 6. B Decrements in inhibition weights during prolonged binocular rivalry under different attention conditions. Green bars indicate inhibition weight decrements for monocular neurons selective for stimuli presented to the left eye (changes of LE1 bold blue curve in A), and blue bars indicate those for the right eye (changes of RE2 bold green curve in A). C The average normalized proportion of exclusivity plotted against time in binocular rivalry experiments. Replotted with permission from Klink et al.34. Dashed line shows the baseline. Error bars denote 1 SEM. D Simulated results from binocular rivalry in the attended condition.

The inhibition weights for monocular neurons selective for the presented stimuli decreased, with these inhibitory changes depending on attention levels (Fig. 7B; also see Supplementary Fig. 4). Weights remained stable in the absence of attention (Supplementary Fig. 4D), suggesting that attention played a critical role in the plasticity of prolonged binocular rivalry. This prediction should be tested in future experiments. Further, the inhibition weights for monocular neurons selective for the unpresented stimuli remained unchanged. Consequently, if the competing stimuli presented to each eye were abruptly switched after a period of binocular rivalry, the proportion of exclusive percepts would revert to baseline, in line with previous empirical findings (Klink et al.34, Experiment 2; see Supplementary Information: Changes of Inhibition in Binocular Rivalry for details).

The anti-Hebbian model reproduces eye-based attention effects on ocular dominance plasticity

Recent studies indicate that ocular dominance can be influenced by eye-based attention when two eyes view non-fusible images. For example, when one eye views inverted images through a prism35 or movies played backward37, while the other eye views normal images, the eye exposed to abnormal stimuli tends to dominate in subsequent binocular rivalry. In these situations, both eyes receive dynamic stimuli with equal intensity but different phases. It is proposed that the eye viewing coherent, intuitively presented stimuli captures stronger attention compared to the eye exposed to abnormal inputs35,37. This relative reduction in attention to the eye with abnormal stimuli enhances its ocular dominance, reflecting a plasticity effect akin to short-term monocular deprivation.

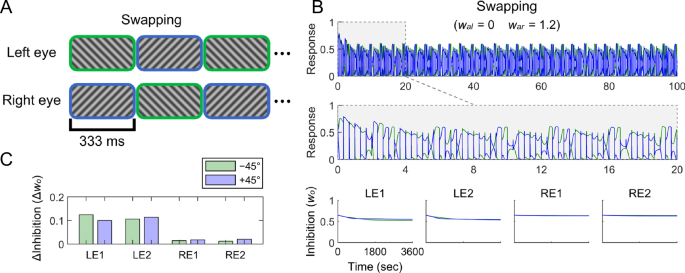

Our model predicts that an imbalance in attention between the two eyes leads to a corresponding imbalance in their neuronal responses, with the unattended eye producing weaker responses than the attended eye. The anti-Hebbian learning mechanism would then decrease the inhibition onto the weaker (unattended) eye, resembling the effects observed in monocular deprivation. To test this hypothesis, we simulated this plasticity induced by eye-basted attention. In the simulation, the input stimuli were simplified to dichoptic orthogonal gratings that swapped rapidly and repeatedly47,59 (Fig. 8A). This swapping regime captured the essential properties of experimental procedures in which each eye’s stimuli continuously varied but were equal in intensity and differed in phase. Greater attention was assigned to the right eye. Simulation results revealed that the inhibition weights onto the unattended eye decreased over time, whereas those onto the attended eye remained stable (Fig. 8B–C). Consequently, the unattended eye (i.e., the left eye) experienced reduced interocular suppression and showed enhanced ocular dominance, consistent with experimental observations.

A Stimuli in swapping simulations. Dichoptic orthogonal gratings were swapped rapidly and repeatedly at 3 Hz. B The simulated responses of two binocular summation neurons in the first 100 and 20 s of swapping simulations (upper and middle panels), and the simulated changes of inhibition weights (w_{o}) (lower panel). (w_{al}) and (w_{ar}) indicate the attention weights for the left and right eyes, respectively. The significance of curves aligns with that described in Fig. 6. C Decrements in inhibition weights during swapping. LE1, LE2 represent left monocular neurons selective for two orientations, −45° and +45° from vertical, respectively. RE1, RE2 represent right monocular neurons selective for the two orientations. Green and blue bars indicate decrements in inhibition weights from opponency neurons selective for −45° and +45°, respectively.

Discussion

We investigated short-term monocular deprivation across different attention levels and found that removing attention from monocular stimuli significantly diminished the deprivation effect. This highlights the essential role of attention in binocular visual plasticity, although this plasticity is typically thought to occur at the early stages of visual processing26,27,29,60. To explore the neural mechanisms underlying this plasticity and its attention dependence, we developed a computational model that incorporated an anti-Hebbian learning rule into the existing attention model of binocular rivalry47. Intriguingly, our model successfully simulated not only the attention-dependent enhancement of predominance of the deprived eye in deprivation but other forms of binocular plasticity, including the plasticity in binocular rivalry32,34 and the binocular plasticity induced by eye-based attention35,37. These findings strongly suggest that anti-Hebbian learning plays a fundamental role in the neural mechanisms of binocular plasticity.

Computational mechanisms

Our model offers a potential mechanistic explanation for the neural computations underlying short-term monocular deprivation and other forms of binocular plasticity. It posits that during deprivation, opponency neurons driven by the non-deprived eye—responsible for detecting binocular discrepancies and inhibiting the deprived eye’s activity—are strongly activated, whereas monocular neurons of the deprived eye remain inactive. This activity mismatch triggers anti-Hebbian learning34, gradually reducing the inhibition weights between these neurons and weakening the interocular suppression of the deprived eye. In contrast, opponency neurons driven by the deprived eye remain inactive and fail to initiate anti-Hebbian learning, thereby leaving the inhibition onto the non-deprived eye unchanged. Consequently, the deprived eye exhibited increased predominance following deprivation. These model predictions align with earlier findings on short-term monocular deprivation, which observed increased predominance for the deprived eye22,23, and psychophysical results showing reduced interocular suppression of the deprived eye without impacting the non-deprived eye30,31. Further, a previous MRS study reported that monocular deprivation reduces resting GABA concentrations in V1, with this reduction strongly correlating with the perceptual boost of the deprived eye29. These findings suggest the involvement of V1 GABAergic neurons in deprivation effects, supporting our hypothesis that attenuated inhibitory synaptic connections underlie short-term monocular deprivation. Similarly, during prolonged binocular rivalry, asynchrony between active opponency neurons driven by the predominant eye and inactive monocular neurons of the non-predominant eye led to gradual decreases in inhibition weights onto the non-predominant eye. As eye dominance continues to alternate, the progressive weakening of inhibition impacts both eyes, resulting in an increased frequency of mixed percepts as binocular rivalry unfolds32,34.

Our model also simulates and elucidates the attention dependence of the deprivation effects, as observed in our psychophysical experiment. During monocular deprivation, attention is directed primarily toward the non-deprived eye, whereas the deprived eye receives minimal attention because of the lack of stimuli. This heightened attention gain on monocular neurons of the non-deprived eye amplifies the activity of corresponding opponency neurons, thereby promoting anti-Hebbian learning at inhibitory connections from the non-deprived eye to the deprived eye. Consequently, attention expedites the weakening of interocular suppression onto the deprived eye, thereby intensifying the deprivation effect. Conversely, when attention shifts away from monocular stimuli, the attention gain decays and the activity of opponency neurons driven by the non-deprived eye remains at baseline, insufficient to drive anti-Hebbian learning. Therefore, without attention, interocular suppression remains unchanged during deprivation, leading to an abolished or substantially reduced deprivation effect. Further, our model accounts for prior findings that eye-based attention induces ocular dominance plasticity. Directing sustained attention toward one eye during prolonged exposure to infusible stimuli enhances the subsequent dominance of the unattended eye35,37,61. According to our model, heightened activity of opponency neurons driven by the attended eye facilitates anti-Hebbian learning at inhibitory connections from the attended eye to the unattended eye, ultimately enhancing the dominance for the unattended eye.

Neural mechanisms

Short-term monocular deprivation is considered a form of homeostatic plasticity22,29, which involves compensatory processes that restore neuronal responses to a baseline set point following perturbations, such as those induced by Hebbian learning, thereby stabilizing neural activity62,63. Several mechanisms may drive homeostatic plasticity, including synaptic scaling62,64,65, plasticity of intrinsic excitability64,66,67, and adjustments in the excitation-inhibition balance within neural networks68,69,70,71,72. Cell-wide forms of homeostatic plasticity typically operate over several days. For instance, synaptic scaling relies on the sensing of glutamate concentrations and the release of TNF-α by glial cells, processes that take several days to fully develop73,74. In contrast, adjustments in the excitation-inhibition balance occur much more rapidly, as they are mediated by Hebbian/anti-Hebbian plasticity, which operates on a timescale of milliseconds to hours75. Our studies, alongside prior research, demonstrate that the effects of short-term monocular deprivation emerge within just tens of minutes24,25,50,76,77—well within the timescale of Hebbian/anti-Hebbian plasticity. Our model provides a specific framework suggesting that Hebbian learning at inhibitory synapses connecting monocular neurons is the precise mechanism underlying this homeostatic plasticity phenomenon.

The reduction of inhibition following sensory deprivation as a rapid mechanism of homeostatic plasticity has been supported by recent neurophysiological studies. For instance, monocular deprivation in adult mice reduces inhibitory synapses in the visual cortex71,78, and when binocular vision is restored, inhibitory synapses continue to decrease, resulting in heightened responsiveness to the previously deprived eye78. Conversely, one-day whisker stimulation increases inhibitory synapses in the barrel cortex79. Although the rapid homeostatic plasticity observed in these studies may not exactly replicate short-term monocular deprivation, they support the idea that rapid homeostatic plasticity via anti-Hebbian learning, as suggested by our model, has a corresponding physiological basis72,80.

An essential component of our model is the opponency neurons, which compute the difference between signals from the two eyes47,48. Functioning as XOR (exclusive-OR) logic gates, they activate only when signals from the two eyes differ significantly and send inhibitory signals to the contralateral eye48,81. These neurons have been identified in neurophysiological studies82,83,84 and psychophysical experiments48,85,86. However, opponency neurons may not constitute distinct neuronal types. Recent evidence indicates that monocular neurons in V1 exhibit binocular opponency properties5. For instance, most monocular neurons respond robustly to preferred stimuli in the dominant eye but are significantly inhibited when the same stimuli are concurrently presented in the non-dominant eye5. Therefore, it is possible that monocular neurons not only perform their sensory representation functions but also execute the computational role of opponency neurons.

Alternative models

While neural plasticity can occur at various neural connections, additional modeling indicated that plasticity at other connections in this model—such as from monocular to opponency neurons, monocular to binocular neurons, or binocular to attention neurons—failed to account for the experimental results (see Supplementary Information: Alternative Models for details). Our findings strongly suggest that plasticity at interocular inhibitory connections is the fundamental mechanism underlying short-term binocular plasticity.

Some researchers suggest that short-term binocular plasticity may be mediated by the long-term adaptation of visual neurons. For instance, the deprived eye could be released from contrast adaptation owing to the lack of visual input27,87, or robust activation and subsequent adaptation of opponency neurons driven by the non-deprived eye could reduce interocular suppression onto the deprived eye37,61. These adaptation-based explanations predict a shift in ocular balance favoring the deprived eye after monocular deprivation. However, some have argued that short-term binocular plasticity and adaptation are two separate processes, as they exhibit distinct characteristics and may involve different neural mechanisms88. To explore whether adaptation alone accounted for our experimental results, we developed a model incorporating a long-term adaptation mechanism while excluding the anti-Hebbian learning mechanism48 (see Supplementary Information: Alternative Models for details). Our simulations revealed that although the long-term adaptation mechanism could produce enhanced dominance of the deprived eye following monocular deprivation, it failed to effectively capture the critical role of attention in this process. The deprivation effects were only limitedly influenced by attention and remained strong even under the no-attention condition (Supplementary Figs. 14–16). Therefore, the long-term adaptation mechanism alone cannot fully account for all binocular plasticity phenomena and attentional modulation effects, and is unlikely to be the sole mechanism involved.

The most notable distinction between our model structure, based on Li et al.47, and other rivalry models is the inclusion of opponency neurons and attention neurons. Most existing rivalry models employ direct mutual inhibition between monocular neurons to generate competition between the two eyes81,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96. While incorporating the Hebbian learning rule into interocular inhibitory connections in these conventional models may simulate the short-term plasticity observed in monocular deprivation and binocular rivalry, these models still exhibit key limitations. Specifically, in these models, plaid stimuli elicit strong rivalry between their component orientations47,48,96, which would predict a reduction in exclusive perception during binocular rivalry after prolonged viewing of plaid stimuli. This obviously does not align with experimental observations. In contrast, our model’s opponency neurons do not respond to binocular plaid stimuli, thereby avoiding strong plaid component rivalry48. Consequently, typical binocular rivalry plasticity phenomenon does not occur after prolonged exposure to plaid stimuli in our model. Furthermore, conventional models typically treat binocular inhibition as an automatic process driven solely by bottom-up sensory inputs, without considering the potential involvement of attention47. Therefore, these models cannot simulate the modulation of binocular plasticity by attention.

Limitations and future directions

Our model incorporates multiple processes, including attention, inhibitory plasticity, and interocular suppression, thus generating several testable predictions regarding these processes: (1) The plasticity observed during prolonged binocular rivalry should also be influenced by attention. Reduced attention to rivalry stimuli is predicted to decrease interocular inhibition changes, consequently leading to a diminished trend in the reduction of exclusive percept durations over time (Fig. 7B; also see Supplementary Fig. 4). (2) The reduction in interocular inhibition during prolonged binocular rivalry exhibits direction specificity (Fig. 7A; also see Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, the abrupt switching of competing stimuli between eyes during rivalry is predicted to reset the proportion of exclusive percepts to baseline levels. (3) Our model suggests that short-term binocular plasticity is mediated by plasticity in interocular inhibitory synapses, which primarily rely on the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA29,97,98,99. We predict that short-term binocular plasticity phenomena, such as short-term monocular deprivation effects, would be weaker in individuals with immature or atypical GABAergic systems, such as children100 and individuals with schizophrenia101 or autism102. All these predictions should be empirically tested in future studies.

Various non-visual factors can modulate short-term binocular plasticity, including physical exercise103,104,105,106,107, energy metabolism108, motor plasticity109, working memory109, and sleep110. Some factors, such as physical exercise, may enhance overall attention, thereby amplifying deprivation effects. By contrast, others may primarily influence the efficiency of synaptic learning by modulating the time constant (tau_{w}) in our model. However, the specific mechanisms underlying these effects require elucidation.

To facilitate the manipulation of attention, we employed an extremely short-term (15 min) monocular deprivation rather than conventional short-term (2–3 h) deprivation. Prior research has indicated that 15 min of deprivation is sufficient to induce relatively weak and short-lived shifts in ocular dominance25,50. The deprivation effect strengthens with increased duration, peaks at approximately 3–5 h, and then gradually declines76. Some researchers, such as Kim et al.50, suggest that extremely short-term deprivation represents the same form of homeostatic plasticity as traditional short-term deprivation. Additionally, Han et al.77 noted that both the short-term interocular suppression paradigm and traditional eye-patching paradigm tapped into similar mechanisms involving GABAergic circuits in V129,97,98,99. However, there is currently no conclusive evidence determining whether the neural mechanisms underlying short-term monocular deprivation of varying durations are identical or distinct25. This question warrants further investigation in future studies.

Our experimental paradigm may be reminiscent of flash suppression, a phenomenon in which presenting one half of a binocular rivalry pair for a few seconds before showing the other half causes the initial image to be removed from awareness during subsequent binocular rivalry111,112. This effect has been attributed to a monocular adaptation mechanism111,112,113 in which monocular neurons activated by previewed stimuli become adapted and less dominant during subsequent rivalry114,115,116. Supporting this view, studies have shown that high-contrast prior stimuli typically induce flash suppression, whereas low-contrast prior stimuli lead to flash facilitation111,117. In contrast, our study investigated the effects of short-term monocular deprivation lasting tens of minutes, hypothesizing that it engages interocular suppression at the binocular interaction stage rather than monocular mechanisms. However, there is currently no direct evidence to confirm or refute whether the anti-Hebbian learning-based disinhibition mechanism also contributes to flash suppression. If Hebbian-based homeostatic plasticity can occur rapidly, similar to the normalization reweighting process that maintains population homeostasis within seconds118,119,120, flash suppression might involve comparable inhibitory plasticity mechanisms.

In our model, the algorithmic implementation of plasticity serves as a simplified computational principle intended to provide a potential explanation for binocular plasticity, thus avoiding delving into details of the underlying circuit, cellular, molecular, and biophysical mechanisms47. While this model may not capture the full complexity of this plasticity, it lays the foundation for developing more sophisticated models in the future. In addition, our model neurons consist of separate classes; however, in the visual cortex, the boundaries between neuron classes are blurred owing to intricate feedforward, lateral, and feedback connections5. Moreover, binocular information integration is a multistage process91,121, whereas our model focuses on only one stage. Despite this limitation, the computations performed may have broader applicability. Future models could explore binocular plasticity within the framework of multistage visual processing.

In summary, our findings elucidate the neural computational mechanisms underlying binocular plasticity and clarify the link between visual plasticity and attention. These insights may extend to plasticity in other forms of short-term sensory imbalance and offer valuable implications for the development of machine-learning algorithms incorporating artificial neural networks and attention mechanisms. Moreover, our findings hold potential for developing novel and efficient treatments for amblyopia and other sensory plasticity-related conditions.

Methods

Psychophysics

Observers

Twelve male and ten female observers (mean age, 20.6 years; range, 18–24 years) participated in the psychophysical experiment. The sample size was determined based on previous studies that investigated short-term monocular deprivation effects29. All observers had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity and normal stereopsis, and provided written informed consent. The experiments were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Board of Zhejiang University. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Apparatus

Visual stimuli were generated using MATLAB R2014a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) with the Psychophysics Toolbox 3.0122,123 on a Windows computer, and presented on a linearized CRT monitor (22” Hewlett-Packard P1230 or 17” Sony G220; 1024 × 768 resolution; 100 Hz refresh rate; 44.5 cd/m2 mean luminance; 60 cm viewing distance). Observers viewed pairs of monocular stimuli dichoptically through a mirror-stereoscope with the head comfortably stabilized by a chin rest.

Stimuli and procedure

Observers completed all three experimental conditions (attended, fixation, and unattended) in a balanced order over three consecutive days. Each condition was separated by at least 6 h and typically by one day. Each experimental condition comprised three phases: pre-deprivation binocular rivalry, monocular deprivation, and post-deprivation binocular rivalry. Throughout each binocular rivalry phase, orthogonal sinusoidal gratings (orientation, −45° and +45° from vertical respectively; contrast, 35%; spatial frequency, 2 cycles/degree) centered in a circular window (diameter, 3°) with a raised-cosine blurred edge (width, 0.42°) were presented dichoptically to the two eyes, and observers continuously reported which grating they exclusively perceived by maintaining pressing on the corresponding key. When mixed percepts occurred, observers did not press any keys. Each binocular rivalry phase lasted for 6 min without interruption.

During the 15-min monocular deprivation phase, a rapid sequence of colorful outdoor scenes (randomly drawn from a pre-collected image library containing 455 images, subtending 3.7° × 3.7° visual angle) was presented to the non-deprived eye at a frequency of 10 Hz, while a blank screen was presented to the deprived eye. A series of ellipses (major axis, 0.4°; minor axis, 0.35°) with orientation and color changing continually, appeared in the fovea of both eyes within a circular aperture surrounding the fixation point. The ellipse randomly switched between red and gray in color and between horizontal and vertical in orientation every second. These color and orientation changes were independent of each other, with no repeated combinations presented continuously. Following the deprivation phase, a 10-sec interval of binocular fusion frames was presented before the onset of the post-deprivation rivalry phase.

The monocular deprivation phase involved three levels of attention: fixation, unattended, and attended. In the fixation condition, observers maintained their fixation on the central point and ellipses, passively viewing scene images in the parafovea without making any judgments about the ellipse or the scenes. In the unattended condition, observers performed a demanding color-shape conjunction detection task (adapted from Zhang et al.51). While maintaining their gaze on the central point and ellipses, they ignored the scenes and focused attention solely on the task in the fovea. Observers pressed a key when encountering a vertical red or horizontal gray ellipse while refraining from responding to the other two ellipse types (i.e., horizontal red or vertical gray). Feedback tones were delivered when observers missed or misreported an ellipse. In the attended condition, observers maintained fixation on the central point and ellipses, and detected randomly inserted butterfly images. These infrequent images were included to encourage sustained attention to the sequence of outdoor scenes. Feedback tones were delivered when observers missed or misreported a butterfly image.

Selection of the deprived eye was balanced across observers. Half the observers were deprived of their dominant eye, whereas the other half were deprived of their non-dominant eye. Each observer’s dominant eye was determined based on the pre-deprivation rivalry test in the first session, with the eye exhibiting greater predominance identified as the dominant eye. Observers were not informed which eye would be deprived. To counterbalance any potential bias for orientation during binocular rivalry, the stimulus orientation for each eye was balanced across observers.

Model fitting analysis

The change in predominance of the deprived eye over time during post-deprivation rivalry phase was quantified using an exponential decay model as follow50:

where (beta_{1}) represents the initial impact of deprivation on ocular dominance, (beta_{2}) represents decay rate, and (beta_{0}) represents baseline predominance of the deprived eye measured from pre-deprivation rivalry phase. (beta_{1}) and (beta_{2}) are free parameters while (beta_{0}) is a fixed parameter. A non-linear regression model was used to fit the values of (beta_{1}) and (beta_{2}), and showed good fits for different experimental and simulation conditions.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses were performed using JASP (Version 0.18.1). Two-way repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to analyze the predominance of the deprived eye, the normalized mean dominance duration of the deprived and non-deprived eyes, and the proportions of exclusive and mixed perception. Post hoc tests following significant interactions were conducted using Bonferroni corrections to control the false positive rate in multiple statistical comparisons. One-way ANOVAs were conducted to analyze the intercept and slope of the exponential function fitting the deprivation effects in predominance. When the assumption of homogeneity of variances was violated, Welch’s ANOVAs were applied to correct for the heterogeneity of variances, and Games-Howell tests were used for post hoc tests. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with the significance level set at α = 0.05.

Computational modeling

Model

The fundamental structure of our model (Fig. 5), which depicted sensory representation, attentional modulation, and mutual inhibition, was derived from the binocular rivalry model of Li et al.47. Sensory representations were implemented using two monocular populations and one binocular summation population. The response of the left-eye monocular neuron (R_{l1}), selective for orientation 1, was computed as follows:

The responses of all four monocular neurons were characterized by similar expressions. The subscripts l and r denote the left and right eyes, respectively, and the subscripts 1 and 2 denote the two orientations. The response of monocular neurons over time was derived from excitatory drive ((E)), suppressive drive ((S)), and adaptation ((H)). The excitatory drive was determined by the input ((D)), inhibited by the pooled responses of the opponency neurons ((O_{r})) that responded to the opposite eye, and amplified by an attention gain ((1+w_{a}R_{a1})). (w_{o}) and (w_{a}) were the weights of mutual inhibition and attentional modulation, respectively. ({[]}_{+}) denote half-wave rectification. The values of (n) and (sigma) were the slope and the contrast gain of the contrast-response functions of the neurons, respectively, and (alpha) determined the maximum response. (tau_{s}) was the time constant of the monocular and binocular summation neurons. (tau_{h}) and (w_{h}) were the time constant and the weight of neurons’ self-adaptation, respectively.

The response of the binocular summation neuron (R_{b1}), selective for orientation 1, was computed as follows:

The responses of both binocular neurons were characterized by similar expressions. The subscript b denotes binocular neuron. The responses of binocular neurons were determined by excitatory drive ((E), derived from the pooled responses of monocular neurons), suppressive drive ((S)), and adaptation ((H)).

Attentional modulation was executed by a pair of attention neurons. Attention gain fluctuated between two sensory representations and the orientation with stronger sensory responses received a greater share of attention gain47. The response of the attention neuron (R_{a1}) that preferred orientation 1 was computed as follows:

The responses of both attention neurons were characterized by similar expressions. The subscript a denotes attention neuron. (tau_{a}) was the time constant of attentional modulation. As attention alternated between the two orientations, the difference in responses of the two binocular summation neurons dictated the excitatory drive of attention neurons.

Mutual inhibition between the eyes was achieved by opponency neurons. The response of the right-minus-left (RE-LE) opponency neuron (R_{or1}), selective for orientation 1, was computed as follows:

The responses of all four opponency neurons were characterized by similar expressions. The subscript o denotes opponency neuron, and the subscript r denotes the RE-LE opponency neuron. (tau_{o}) was the time constant of the opponency neurons. The excitatory drive ((E_{or1})) was the difference of monocular responses between the two eyes. (O_{r}) was the pooled response of the two RE-LE opponency neurons.

In our model, during binocular rivalry or monocular deprivation, the inhibition weight (w_{o}) was dynamically adjusted according to anti-Hebbian learning mechanisms53,54,124,125. This process gradually reduced the inhibition weights (w_{o}) from opponency neurons of the predominant eye to contralateral monocular neurons, driven by asynchrony between pre- and postsynaptic activity. Importantly, the reduction in inhibition occurred only when opponency neuron activity exceeds a presynaptic threshold. This constraint ensured that the inhibition onto monocular neurons of the predominant eye remained unchanged.

The inhibition weight onto left-eye monocular neurons selective for orientation 1 from RE-LE opponency neuron selective for orientation 2 (w_{ol12}) was computed as follow:

There were eight inhibition weights in total and they were characterized by similar expressions. (tau_{w}) was the time constant that controlled the learning rate of synaptic weights. (theta_{R_{or}}) and (theta_{R_{l}}) were the pre- and postsynaptic learning thresholds, respectively.

Our use of the term “anti-Hebbian” follows the convention introduced by Barlow and Foldiak53, who described a Hebbian learning rule on inhibitory connections that decorrelates pre- and postsynaptic activity, and therefore termed it “anti-Hebbian”. In models where neurons are connected by modifiable inhibitory weights, initially positive correlations between two neurons lead to a gradual strengthening of inhibition, thereby reducing their correlation54. This term has since been used in several studies on inhibitory plasticity34,126,127.

Causality is a prominent feature of Hebbian learning128, whereby the order of pre- and postsynaptic firings determines whether long-term potentiation (LTP) or depression (LTD) occurs129. To simulate the effects of LTP and LTD, the model incorporated learning thresholds in Hebbian learning130, where the pre- and postsynaptic learning thresholds are the average responses of pre- and postsynaptic neurons over a prolonged period131. As this model used firing rates rather than spike trains and did not capture the precise timing of neuronal activity, presynaptic activity was half-wave rectified to reflect the causal nature of synaptic learning, allowing learning to be triggered by presynaptic firing130.

It is worth noting that using learning thresholds (i.e., the covariance rule) to implement Hebbian learning has a potential flaw in that the synaptic weights may fail to converge to stable values. This occurs because, according to the covariance rule, if two neurons are frequently active together (or apart), their synaptic connection will continue to strengthen (or weaken)130. To address this potential instability, we constrained the inhibition weights to a reasonable range of [0, 0.65].

Following Li et al.47, the model emulated neural responses in MATLAB using forward Euler’s method with a time step of 5 ms. The parameters of synaptic plasticity employed in simulations are listed in Table 1.

Simulation of plasticity in monocular deprivation

In our psychophysical experiment, one eye underwent deprivation, while the other eye received a rapid sequence of colorful outdoor scenes. These scene images should include −45° and +45° orientation components in equal proportions, and the orientations should change continuously and dynamically. For simplicity, our simulation focused solely on these two orientations, assuming that their alternations mirrored the dynamic orientation changes in the switching scenes. Across the parameter conditions investigated, switch frequencies ranging from 0.05 to 100 Hz produced similar effects. However, the magnitude of the effect depended on the temporal characteristics of both the neurons and stimuli. Consequently, an alternation frequency of 2 Hz was selected to produce moderately strong effects that closely matched the experimental results.

Simulation of ocular dominance changes after monocular deprivation

The simulations of monocular deprivation presented above revealed a gradual reduction in interocular inhibition weights (w_{o}) onto the deprived eye during the deprivation period, with the decreasing rate positively correlated with attention strength. These final values of inhibition weights were used as the initial values for post-deprivation rivalry simulations (6 min). Prior to monocular deprivation, we conducted binocular rivalry simulations with a set initial value (0.65) assigned to inhibition weights. The resulting rivalry period provided a baseline for computing the predominance of the deprived eye and the normalized dominance durations after deprivation.

To quantify changes in the proportion of mixed and exclusive perception during binocular rivalry, we computed a perceptual index as follow48:

where (R_{b1}) and (R_{b2}) were the activities of binocular summation neurons selective for the two orientations. The index ranges from -1 to 1, with high values indicating a stronger contribution from the left eye (the deprived eye) and low values indicating a stronger contribution from the right eye (the non-deprived eye). We computed the proportion of time when (P(t)) > 0.4 as the proportion of exclusive perception for the left eye, (P(t)) < −0.4 as the proportion of exclusive perception for the right eye, and (|P(t)|) ≤ 0.4 as the proportion of mixed perception.

Time-dependent changes of short-term adaptation

When our model included only the anti-Hebbian learning mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 7B), it could not precisely capture the upward trend in dominance duration toward the end of binocular rivalry (Fig. 3A), which was previously attributed to the contrast adaptation of rivalry stimuli132,133,134. We simulated this process by gradually weakening the strength of short-term adaptation as binocular rivalry progressed:

The value of (w_{h}) was the weight of short-term adaptation. The value of (k) was the time constant controlling change of short-term adaptation.

This process attenuated the recovery of suppressed neurons from short-term adaptation, leading to prolonged dominance durations in binocular rivalry57. Notably, this mechanism was applied only to binocular rivalry and not to monocular deprivation, in which continuously changing stimuli may reduce changes in short-term adaptation.

Simulation of plasticity in binocular rivalry

The perceptual index (|P(t)|) was bounded by [0, 1], with high values indicating exclusive percepts and low values indicating mixed percepts. We computed the proportion of time with (|P(t)|) > 0.4 as the proportion of exclusive perception over a given period. To replicate the psychophysical experiments of Klink et al.34, we simulated binocular rivalry for approximately 45 min. The proportion of exclusive percepts for the initial 400-sec period was computed and used as the baseline to normalize the proportion of exclusive percepts for the following 19 continuous 110-sec trials. Because of the prolonged simulation duration, the time constant of learning rate (tau_{w}) was increased to 150 s to prevent negative inhibition weights. Notably, the trend in the results remained consistent across different cutoff values and time constants of learning rate.

Simulation of eye-based attention effects on ocular dominance plasticity

We employed a swapping regime to simulate these experiments qualitatively. The right eye was designated as the attended eye with attention weight (w_{ar}) = 1.2, and the left eye as the unattended eye with attention weight (w_{al}) = 0. The simulation ran for 60 min, with stimuli alternating between the two eyes every 333 ms (3 Hz) to prevent abnormal fusion perception and to remain shorter than the time required to produce exclusive percepts of competing stimuli59.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses