The influence of Lactobacillus johnsonii on tumor growth and lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma

Introduction

Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy worldwide, of which papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is the most common subtype1. The increasing incidence of PTC is mainly due to the more frequent use of neck ultrasonography and fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules2. In spite of the favorable prognosis of PTC, it is reported that over half of patients develop cervical lymph nodes metastasis (LNM) which is a major risk factor for disease recurrence3,4. Thus, controlling the LNM of PTC may be an effective measure to further improve the prognosis of patients.

Recent researches have indicated that microbiota, particularly the gut microbiota, is involved in the initiation, progression and dissemination of cancer5. Gut microbiota potentially influence individual’s susceptibility to cancer, and certain bacteria have been reported to accelerate tumor growth and metastatic progression6,7. Besides, microbiota has ability to modify the microenvironment within tumor and could thereby enhance tumor response to therapeutic drugs. Previous research demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation from responders significantly improved tumor-suppressing efficacy of PD-1 blockade, suggesting the potential contribution of the microbiota in tumor treatment8. Specifically, alterations of intestinal microbial community have also been found to correlate with pathogenesis and therapy response of thyroid carcinoma9,10. Yet, considering the thyroid’s anatomical separation from intestine, the precise association and underlying mechanism between thyroid cancer and bacteria remains uncertain.

The relationship between tumor cell with intratumoral bacteria and the initiation, growth, metastasis, and resistance to chemotherapy of tumors is widely acknowledged11. A study conducted on PTC patients revealed notable variations in the intratumoral microbiome characteristics based on patients’ age and tumor stage12. Another study has identified significant differences in microbial diversity and composition between the peritumor and tumor microhabitats of patients with thyroid cancer, with a potential correlation between a higher abundance of Sphingomonas and LNM13. However, there is a scarcity of research examining the involvement of intratumoral bacteria in thyroid cancer. The aforementioned studies solely relied on the analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequencing data and did not conduct experimental investigations to validate their hypotheses.

In this study, we successfully isolated and cultured intrathyroidal bacteria under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Additionally, we established a nude mice LNM model of PTC by subcutaneously injecting a fluorescently labeled PTC cell line. Our findings reveal that intratumoral Lactobacillus johnsonii (L. johnsonii) is more prevalent in non-metastatic PTC, and it exerts inhibitory effects on LNM by suppressing the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process. Significantly, we demonstrated that the oral administration of L. johnsonii can enhance its colonization in the gut and intratumoral regions, suggesting its potential as a novel therapeutic approach to inhibit LNM in PTC.

Results

Intratumoral Lactobacillus was enriched in Non-metastatic PTC

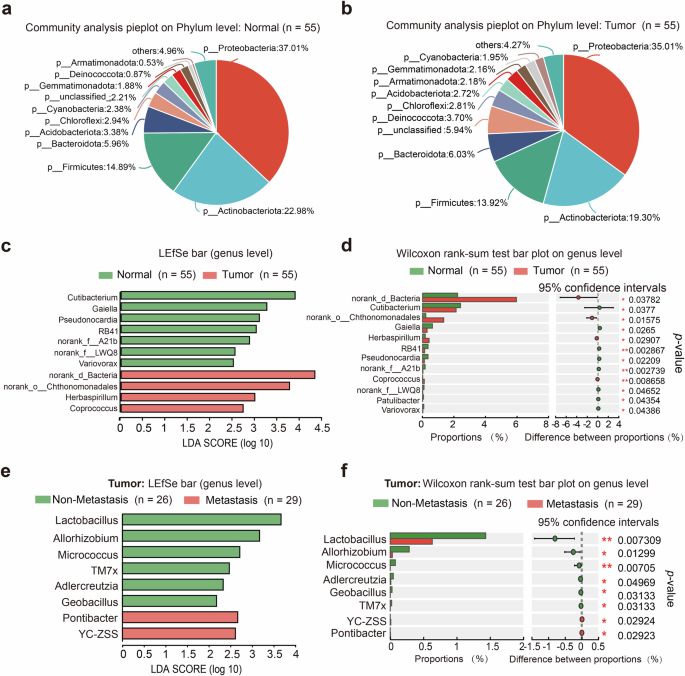

To investigate the impact of intrathyroidal microbiomes on LNM of PTC, we collected tumor tissues and adjacent non-tumor (normal) tissues from 55 PTC patients and performed 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with PTC were shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference in community composition at phylum level between tumor and normal tissue, of which the three predominant bacteria were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, and Firmicutes. (Fig. 1a, b). Subsequent LEfSe analysis at genus level revealed a significant enrichment of Cutibacterium and Gaiella in the normal tissues, while Herbaspirillum and Coprococcus were enriched in tumor tissues (Fig. 1c, d). Moreover, we divided the tumor tissues into two groups by LNM and found that the abundance of Lactobacillus was the most significant difference between the metastasis group (n = 29) and non-metastasis group (n = 26) (Fig. 1e, f).

a Community analysis pieplot of adjacent normal tissues at phylum level. b Community analysis pieplot of tumor tissues on phylum level. c, d Differential distributed taxa by LEfSe between normal and tumor tissues at genus level. e, f Differential distributed taxa by LEfSe in tumors between metastasis group and non-metastasis group at genus level.

Lactobacillus johnsonii was presented in PTC tissues

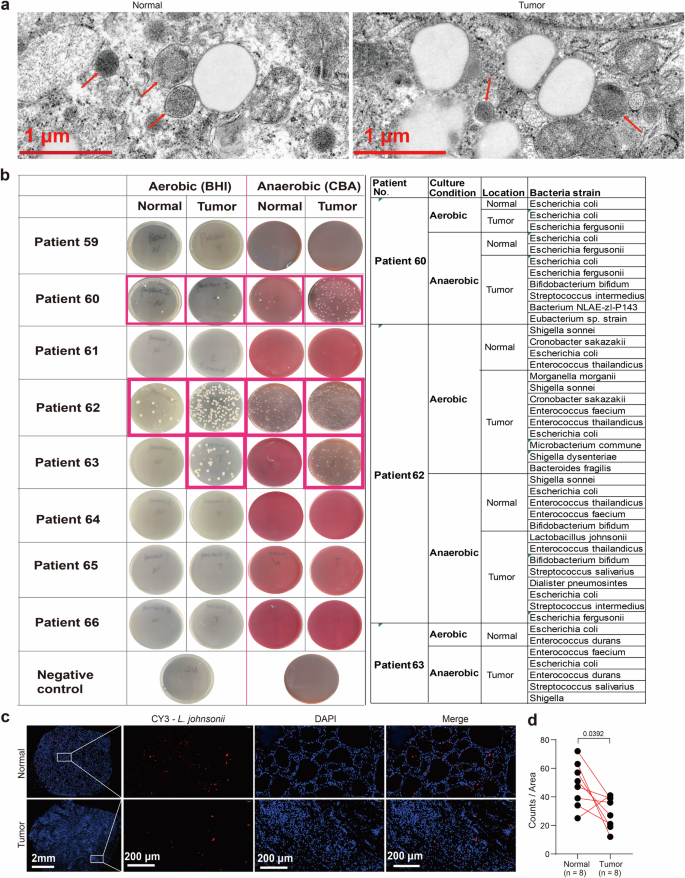

To confirm the presence of bacteria in the thyroid, we utilized high-resolution electron microscopy (EM) analysis, which revealed the presence of bacteria in both tumor and adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 2a). Subsequently, we collected tumor and adjacent normal tissues from 8 additional PTC patients, and the intrathyroidal bacteria isolated from these tissues were cultured under anaerobic and aerobic conditions. As shown in Fig. 2b, colonized bacteria were found in thyroid tissues of 3 patients both under anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Specifically, in Patient Nos. 60 and 62, bacteria could be found both in tumor and normal tissues, while in Patient No. 63, bacteria could be found only in tumor tissue. To identify the specific bacteria strain in these 3 patients, we picked the single colony and ran colony PCR to get the bacteria sequencing. By aligning to the 16S rRNA sequences database in the NCBI BLAST site, we found out that the main bacteria strain was Escherichia coli (E. coli) in Patient No. 60 and No. 63 both under anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Comparatively, Lactobacillus johnsonii (L. johnsonii) was mostly presented in the tumor tissue of Patient No.62 under anaerobic condition (Fig. 2b). Additionally, the 16S sequencing data revealed that L. johnsonii represented the highest proportion of Lactobacillus at the species level in 55 PTC patients (34%) (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We further confirmed the presence of L. johnsonii in both tumor and normal tissues through Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (Fig. 2c). The quantitative statistical analysis of L. johnsonii expression in the 16S-FISH assay revealed that its abundance in normal tissues was significantly higher than in tumor tissues (Fig. 2d).

a EM image of tumor and adjacent normal tissues showing bacteria structures. Red arrows pointing to bacterial structures. Scale bars represent 1 μm. b The bacteria colonized from tumor and normal tissues of 8 additional patients were cultured under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Identification of the particular strains of bacteria in Patient Nos. 60, 62, and 63 through the utilization of colony PCR and the alignment of 16S rRNA sequences with the NCBI 16S BLAST database available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST. c, d Detection of L. johnsonii in the CRC tissues from patients by FISH. n = 8 biologically independent samples for each group. Scale bars represent 2 mm or 200 μm as labeled.

Lactobacillus johnsonii suppressed proliferation, invasion and migration of human PTC cells via inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin pathway

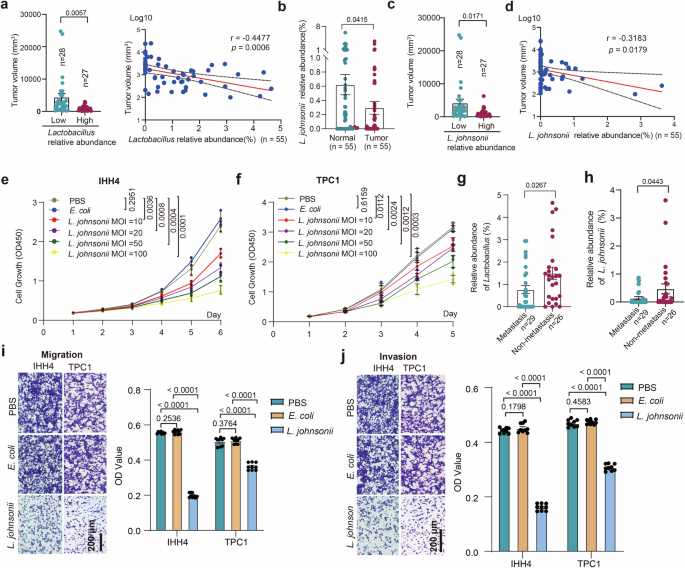

To investigate the roles of Lactobacillus in PTC, we examined the correlation between tumor volume and the abundance of Lactobacillus in 55 PTC patients. The 55 PTC patients were divided into two groups according to the median abundance value of Lactobacillus. As shown in Fig. 3a, the group with low abundance of Lactobacillus exhibited larger tumor sizes than the other group with high abundance of Lactobacillus. The correlation analysis showed that there was a significant negative correlation between the abundance of Lactobacillus and tumor volume. The representative sequence of each ASV belonging to Lactobacillus was further aligned to the NCBI 16S BLAST database to identify the ASV of L. johnsonii. As shown in Fig. 3b, the abundance of L. johnsonii was significantly lower in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues. Consequently, the 55 PTC patients were divided into another two groups according to the median abundance value of L. johnsonii. Similarly, group with low abundance of L. johnsonii also exhibited larger tumor sizes than that with high abundance of L. johnsonii. (Fig. 3c), indicating a significant negative correlation between the abundance of L. johnsonii and tumor volume (Fig. 3d). We evaluated cell proliferation of IHH4 and TPC1 cells treated with different MOI of L. johnsonii. As shown in Fig. 3e, f, the higher MOI of L. johnsonii initially introduced, the more slowly the IHH4 and TPC1 cells proliferated.

a Tumor volumes of PTC patients with high or low abundance of Lactobacillus, and the correlation analysis between the abundance of Lactobacillus and tumor volume. b The abundance of L. johnsonii in tumor and normal tissues. c Tumor volumes of PTC patients with high or low abundance of L. johnsonii. d The correlation analysis between the abundance of L. johnsonii and tumor volume. e, f CCK8 cell proliferation curve for IHH4 (e) and TPC1 (f) cells stimulated with indicated MOI of L. johnsonii. g, h Relative abundance of Lactobacillus (g) and L. johnsonii (h) in tumor tissues between PTC patients with or without LNM. i, j Transwell assay evaluated the migration (i) and invasion (j) abilities of IHH4 and TPC1 cells stimulated with L. johnsonii. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Scale bars represent 200 μm.

According to the findings depicted in Fig. 3g, h, there was a significant reduction in the relative abundances of Lactobacillus and L. johnsonii in tumor tissues with LNM compared to those without LNM. To investigate the potential impact of L. johnsonii on the invasion and migration of PTC cells, a Transwell invasion and migration assay was conducted using IHH4 and TPC1 cells co-cultured with L. johnsonii. As shown in Fig. 3i, j, L. johnsonii significantly inhibited the invasion and migration ability of IHH4 and TPC1 cells compared with cells co-cultured with E. coli (isolated from PTC) or 1×PBS as negative controls.

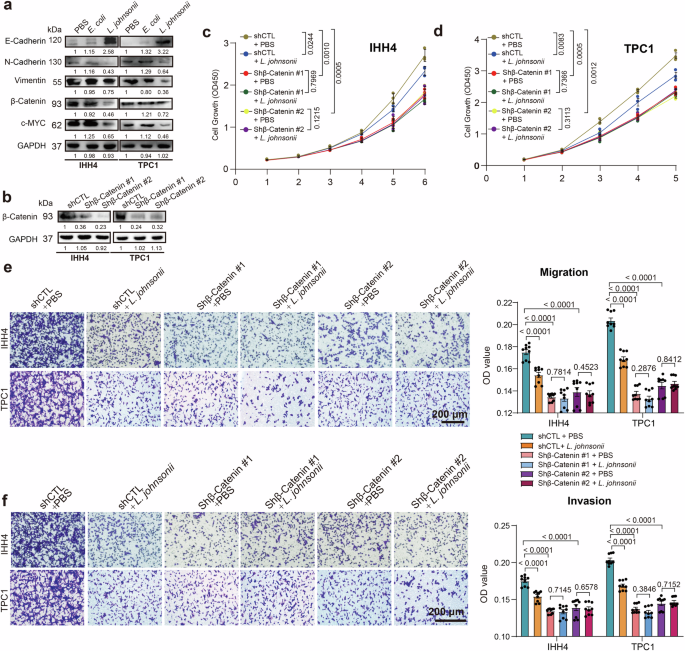

Previous study suggested that L. johnsonii could regulate the β-catenin pathway to inhibit the metastasis of colorectal cancer. We wondered whether β-catenin signaling pathway was involved in L. johnsonii suppressing PTC growth and metastasis, and detected the related proteins. The results showed that β-catenin, c-MYC, N-cadherin and Vimentin was down-regulated, accompanied with markedly up-regulated E-cadherin in IHH4 and TPC1 cells after co-cultured with L. johnsonii (Fig. 4a). Following the inhibition of β-catenin expression in IHH4 and TPC1 cells using shRNA (Fig. 4b), the inhibitory effects of L. johnsonii on tumor cell growth, migration, and invasion were markedly reduced (Fig. 4c–f). These results indicate that L. johnsonii exerts its antitumor effects primarily by suppressing the β-catenin signaling pathway.

a Western blot analysis of Wnt/β-catenin pathway in IHH4 and TPC1 cells after co-cultured with L. johnsonii. b β-catenin protein expression in IHH4 and TPC1 cell following transfection with shCTL, shβ-catenin #1 or shβ-catenin #2, as determined by Western blot. c, d CCK8 cell proliferation curves for IHH4 (c) and TPC1 (d) cells transfected with shCTL, shβ-catenin #1, or shβ-catenin #2 following exposure to L. johnsonii or PBS in vitro. e, f Migration (e) and invasion (f) assays of IHH4 and TPC1 cells transfected with shCTL, shβ-catenin #1, or shβ-catenin #2 following exposure to L. johnsonii or PBS in vitro. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Scale bars represent 200 μm.

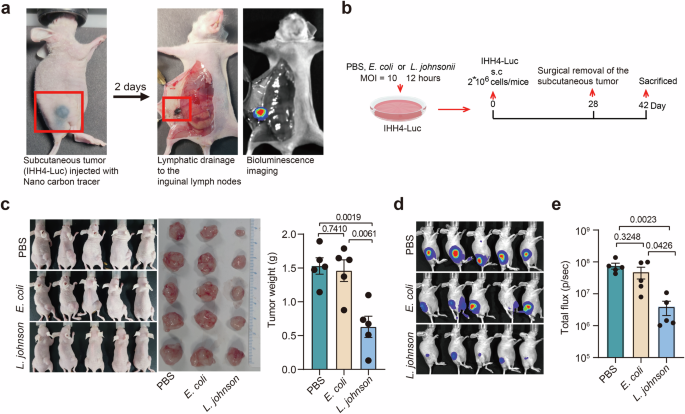

L. johnsonii suppressed tumor growth and LNM of PTC in vivo

A xenograft tumor experiment in nude mice was conducted to verify the potential effect of L. johnsonii on PTC. As shown in Fig. 5a, the IHH4-Luciferase cell line labeled with nano carbon tracer was used to observe tumor formation and metastasis. As described in the “METHODS” section, the mouse LNM model of PTC was established by L. johnsonii, E. coli or PBS pretreated IHH4-Luciferase cells subcutaneously injection and the subcutaneous tumors were excised on day 28 (Fig. 5b). In the L. johnsonii treated group, the size and weight of xenograft tumor were significantly lower compared with the E. coli and PBS treated groups (Fig. 5c, d). Furthermore, after removal of subcutaneous tumor, the L. johnsonii treated group showed a significantly lower LNM rate compared with the E. coli and PBS treated groups (Fig. 5e, f). These results indicated that the L. johnsonii was capable of suppressing tumor growth and metastasis of PTC in vivo.

a The metastatic lymph nodes were labeled by Luciferase and nano carbon tracer. b Schematic representation of protocol of PTC xenograft tumor experiment in nude mice (see details in Methods). c The in vivo tumor growth status of L. johnsonii, E. coli and PBS pretreated groups were demonstrated by photos. d Comparisons of tumor weight among the three groups. e Bioluminescence imaging was used to monitor LNM after removing subcutaneous tumor. f Comparisons of luciferase activity of metastatic lymph node among the three groups. n = 5 biologically independent samples for each group. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

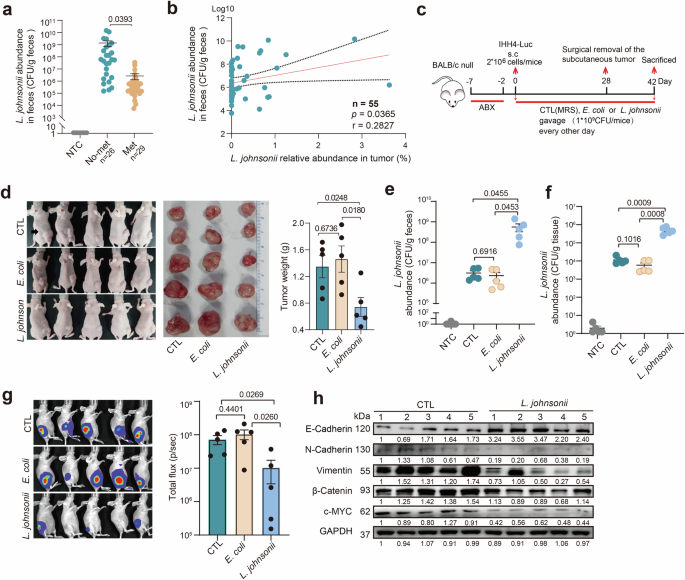

Gut colonization of L. johnsonii inhibited PTC metastatic progression

Considering that the main colonization site of L. johnsonii was gastrointestinal tract and the oral intake was the main way that human get L. johnsonii, we collected fecal tissues from those 55 PTC patients and performed qPCR to detect the abundance of L. johnsonii. The qPCR results indicated that the abundance of L. johnsonii in the feces of metastatic group was significantly lower than that of non-metastatic group (Fig. 6a). The correlation analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between the abundance of L. johnsonii in patients’ tumors and their feces (Fig. 6b). Then we performed gut colonization mice experiment to investigate the impact of L. johnsonii on LNM of PTC. Mice implanted with subcutaneous IHH4-Luciferase cell lines were gavaged with MRS, E. coli, or L. johnsonii after 5-day treatment of antibiotic cocktails (Fig. 6c). Indeed, the xenograft tumor volume and weight (Fig. 6d) were significantly lower in L. johnsonii gavaged group compared with the E. coli and MRS gavaged groups, supporting that L. johnsonii significantly inhibited tumor growth of PTC in vivo.

a qPCR analysis of L. johnsonii abundance in the feces of PTC patients. b The correlation analysis of L. johnsonii abundance between tumors and feces of PTC patients. c Schematic representation of bacterium intestinal colonization experimental protocol in nude mice (see details in Methods). d Photographs demonstrated xenograft mice and their surgically excised tumors from the L. johnsonii, E. coli, and MRS gavaged groups, with a comparison of tumor weights among the three groups. e, f Comparisons of the abundance of L. johnsonii in mice fecal (e) and xenograft tumors (f) between the three groups. g Bioluminescence imaging and luciferase fluorescence of metastatic lymph node in the three groups. h Western blot analysis for Wnt/β-catenin pathway expression in xenograft tumors with or without gut colonization of L. johnsonii. n = 5 biologically independent samples for each group. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

To certify that the tumor suppression was modulated by gut colonization of L. johnsonii, mice fecal and xenograft tumors were collected after 28 days of colonization gavage. Compared with the E. coli and MRS gavaged groups, the abundance of L. johnsonii in mice fecal was significantly increased in L. johnsonii gavaged group (Fig. 6e), and similar results were observed in xenograft tumors (Fig. 6f). Moreover, the LNM of PTC was evaluated by in vivo bioluminescence imaging system, and the fluorescence was significantly decreased in the L. johnsonii gavaged group compared with the E. coli and MRS gavaged groups (Fig. 6g). The above results suggested that L. johnsonii was able to colonize in the gastrointestinal tract and translocate to PTC tissue to further suppress the proliferation and metastasis of PTC cell. To disclose the mechanism underlying this phenomenon, expressions of β-catenin pathway-related proteins in xenograft tumors were examined by Western blot. Consistently, β-catenin, c-MYC, N-cadherin and Vimentin were downregulated accompanied with marked upregulation of E-cadherin in xenograft tumors of L. johnsonii gavaged group compared with the MRS gavaged group (Fig. 6h).

Discussion

Several studies have shown the correlation between gut microbiota and thyroid disease. One study demonstrated that untreated primary hypothyroidism patients can be differentiated from healthy individuals based on the presence of four specific intestinal bacteria (Veillonella, Paraprevotella, Neisseria, and Rheinheimera)14. Another study revealed that individuals with hyperthyroidism exhibit reduced levels of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillaceae15. A separate study found a notable increase in Bacteroides and a significant decrease in Bifidobacterium, while patients not receiving thyroid hormone replacement therapy displayed higher levels of Lactobacillus species compared to those taking oral levothyroxine16. In recent years, there has been an expansion of research on the human microbiome, extending beyond the gut, which is known for its abundance of microorganisms, to previously presumed sterile organs such as the bladder and lungs17,18. In our study, we utilized 16S rRNA gene sequencing and provided preliminary evidence for the presence of bacteria in the thyroid and PTC. To further validate this discovery, we cultured intrathyroidal bacteria isolated from tumor and normal tissues of an additional 8 PTC patients under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Recent evidence suggested that intratumoral bacteria were primarily derived from the digestive tract19. Our result showed that a comparable abundance of L. johnsonii was observed in the subcutaneous PTC tumor gavage with L. johnsonii, suggesting that the intestinal microorganism might translocate to extraintestinal tumor tissue. Bender et al. also reported that probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri translocated to, colonized, and persisted within melanoma20. However, the possibility of direct bacterial infection at the tumor site via blood vessels could not be completely dismissed.

Multiple studies have provided evidence indicating that intratumoral bacteria possess diagnostic significance for various forms of cancer and show intricate correlation with patient prognosis21,22. Extensive researches have elucidated the influence of intratumoral microbiome composition on patient outcomes23, responses to cancer therapies24, and the promotion of cancer metastasis25. Within the realm of genitourinary cancers, investigators have reported a noteworthy decrease in the abundance of Lactobacillus within prostate cancer tissues compared to normal prostate tissues26. Furthermore, previous research has demonstrated a correlation between the scarcity of Lactobacillus in the lower female reproductive tract and the development of cervical cancer27. These findings suggested that Lactobacillus might function as a bacterium that suppressed tumor progression. However, Fu et al. reported an enrichment of Lactobacillus in breast cancer cells, which were found to inhibit the RhoA-ROCK signaling pathway and induce cytoskeletal remodeling25. This mechanism enables tumor cells to withstand mechanical stress within blood vessels, thereby facilitating tumor metastasis. Moreover, through experimentation with germ-free and immunodeficient mice, it has been demonstrated that intracellular bacteria within tumors can promote metastasis autonomously, independent of the intestinal flora and immune system25. In our study, analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequencing data revealed no notable disparities in community composition at the phylum level between tumor and normal tissue of PTC patients. However, a more detailed examination revealed a significant reduction in the abundance of Lactobacillus in tumors with LNM compared to tumors without LNM. These results suggested that Lactobacillus may play a role in inhibiting the LNM of PTC, thereby acting as a tumor suppressor in this context.

Until now, the effect of intratumoral bacteria on tumor metastasis has been widely discussed but the specific mechanism has not been well-established. L. johnsonii has been identified as a potential beneficial bacterium that may improve memory impairment through the brain-gut axis28 and regulate metabolic-related diseases29. Wu et al. have reported that L. johnsonii could alleviate colitis by inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization through modulation of the MAPK pathway30. Furthermore, oral administration of L. johnsonii has been found to enhance levels of tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin in colitis31. It has been observed that L. johnsonii acts as a repair agent for gut mucosal immunity and barrier in the gastrointestinal tract. In our study, we established an in vitro coculture system with L. johnsonii stimulation on IHH4 cells to investigate its effects on human PTC cells. Our findings indicated that L. johnsonii can suppress the proliferation and migration of PTC cells. Additionally, we conducted a xenograft tumor experiment in nude mice to confirm that L. johnsonii can inhibit the LNM of PTC in vivo. Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a crucial role in tumor growth and metastasis. Research indicates that L. johnsonii inhibits the progression of colorectal cancer by suppressing the β-catenin/c-MYC pathway32. Wnt/β-catenin pathway can regulate the transcription of c–MYC to promote tumor growth and facilitate tumor metastasis by regulating EMT-related genes. EMT was known to enhance invasiveness and metastatic potential in solid tumors33. We observed a significant inhibition of the EMT in PTC cells when co-cultured with L. johnsonii. Furthermore, our results showed that after co-cultured with L. johnsonii, there was a decrease in the expression of β-catenin, c-MYC, N-cadherin, and Vimentin, concomitant with a notable increase in E-cadherin levels in IHH4 and TPC1 cells. These findings mark the initial steps in understanding how L. johnsonii influences the LNM in PTC, providing a foundation for further investigation into its mechanisms.

The presence of bacterial communities in the tumor environment, which were also commonly found in the gut microbiome, indicated the potential occurrence of bacterial translocation from the gut to tumors in other locations34. To explore the potential clinical application of treating PTC, we conducted a gut colonization experiment to examine the effect of L. johnsonii on LNM in PTC. However, the absence of mouse PTC cell lines prevented the establishment of an allograft tumor model, thus presenting a methodological constraint in this study. Interestingly, our experiment involved xenograft tumors in nude mice coincidentally revealed that administering L. johnsonii through gavage significantly increased the presence of intratumoral L. johnsonii and inhibited the LNM of PTC. This finding was significant as previous studies have assumed that Lactobacillus colonization in the intestine exerts anti-tumor effects by promoting T-cell activation20,35. However, our results demonstrated that intestinal colonization of L. johnsonii could directly impact tumor cells and inhibit LNM of PTC even in the absence of T-cell involvement. Since the mechanisms of intratumoral bacteria influence tumor biology remain poorly understood, it has been hypothesized that bacteria may indirectly affect LNM of PTC by altering the local inflammation and immune microenvironment after migrating from the gut to the thyroid. However, our findings suggested that L. johnsonii may directly modulate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in PTC cells, thereby inhibiting lymph node metastasis, a process that does not appear to involve inflammation or immune cells. Therefore, the oral consumption of L. johnsonii may hold potential as a treatment modality for PTC.

Inevitably, this study has a few limitations. While our sample size provided valuable insights into the involvement of intratumoral bacteria in PTC, the results must be validated by future study with larger sample size. Furthermore, the absence of a control group consisting of individuals with benign nodules may hinder the interpretation of the results. Comparing the microbial disparities in thyroid tissues between patients with benign nodules and those with PTC would further bolster the observations made in this study.

In conclusion, this study employed 16S rRNA gene sequencing alongside in vitro and in vivo experiments to elucidate the prevalence of L. johnsonii and substantiate its involvement and mechanisms in the LNM of PTC. Our results provided evidence that intratumoral L. johnsonii possesses the ability to impede tumor growth and metastasis in PTC, suggesting that oral administration of L. johnsonii could be a promising therapeutic approach for PTC.

Methods

Mice experiments

Mice experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (CDYFY-IACUC-202308QR020). 5–6 week old female BABL/C nude mice were purchased from Guangzhou GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free condition and fed standard mouse chow. Manual randomization was used to allocate mice to the experiment groups. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

IHH4-Luc cells were plated for 12 h followed by medium replacement with penicillin–streptomycin (P/S) free DMEM (10% FBS) and then co-cultured with bacteria (L. johnsonii or E. coli) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1 for another 12 h under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C. Cells were washed with sterile 1×PBS three times and cultured in DMEM (1% P/S, 10% FBS) medium for 8 h to kill any remaining bacteria. Finally, the cells were collected and injected subcutaneously into BABL/C nude mice (2 × 106 cells/mice) (L. johnsonii, E. coli and PBS pretreated groups; n = 5 in each group; total 15 mice). On day 28, the subcutaneous tumor was surgically resected and the wound was sutured. The metastasis of inguinal lymph nodes was evaluated on day 42 by measuring luciferase fluorescence via In Vivo Imaging System (AniView). Each mouse received an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 200 µL luciferin (15 mg/mL; Meilunbio, #MB1834-2) and the luciferase signal was captured after 10 min. Mice were then sacrificed. For bacterial colonization in gut, mice were given an antibiotic cocktail containing vancomycin (100 mg/L), metronidazole (200 mg/L), ampicillin (200 mg/L) and neomycin (200 mg/L) in the drinking water for 5 days. After 48 h washout period, mice were gavaged with bacteria (1 × 109 CFU/mouse) or MRS every other day until the end of the experiment (L. johnsonii, E. coli and MRS gavaged groups; n = 5 in each group; total 15 mice). IHH4-Luc cells were injected subcutaneously into BABL/C nude mice on day 0, and the subcutaneous tumor was surgically resected and the wound was sutured on day 28. On day 42, the progression of the metastatic lymph nodes was evaluated as described above. The treatment and measurement order were counterbalanced across animals, so that each treatment condition was applied at different times, ensuring no systematic order bias. Tumor size was the primary outcome measure.

Human specimens collection

The fecal samples of PTC patients and PTC paired tumor and normal specimens were collected from the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. PTC patients with LNM (Metastasis group) or without LNM (Non-metastasis group) were recruited in our study. The exclusion criteria included the use of antibiotics within one month, oral and neck infectious diseases, and other concurrent severe organic diseases. Finally, 55 patients were recruited in our study (Metastatic group, n = 29; Non-metastasis group, n = 26). Postoperative pathological results showing positive lymph nodes were defined as the presence of LNM. The protocol of human sample usage and the informed consent were approved by the Ethical Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University [(2023)CDYFYYLK(07-008)]. All patients signed informed consent forms. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Cell lines and bacterial strains culture

IHH4, TPC1 and IHH4-Luciferase (Luc) cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco, #DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, #SV30160) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco, #15140122). The L. johnsonii strains were cultured on Man Rogosa Sharpe (MRS, Oxoid, #CM1175B) plates under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 48 h. E. coli was cultured on Brain Heart Infusion (BHI, BD, #237500) plates under aerobic conditions at 37 °C. All cell lines were purchased from Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (IHH4: CL-0803, TPC1: CL-0643; Wuhan, China).

qPCR quantification

The colonization of L. johnsonii in feces and its translocation in tumor were assessed by qPCR, as previously described25. L. johnsonii DNA was used to plot a standard curve to calculate L. johnsonii DNA concentration in the sample and the steriled enzyme-free water served as negative control (NTC) for the reactions25,36. Tumor and feces were weighted followed by total DNA extraction using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (for tumor, QIAGEN, #69504) or HiPure Stool DNA Kit (for feces, Magen, #D3141-02).

For qPCR quantification, briefly, 10 uL reaction mix containing 3 uL steriled enzyme-free water (Solarbio, #R1600-500ml), 5 uL TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ (TAKARA, #RR420A), 0.5 uL forward primer (5ʹ- TCGAGCGAGCTTGCCTAGATGA-3ʹ), 0.5 uL reverse primer (5ʹ- TCCGGACAACGCTTGCCACC-3ʹ), and 1 uL sample DNA, was loaded on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-time PCR system. Raw cycle threshold (Ct) values were normalized according to a bacterial standard curve produced with L. johnsonii DNA.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Paraffin sections were deparaffinized and then incubated in lysozyme solution (10 mg/mL) at 37 °C. L. johnsonii probes were Cy3-conjugated specific probe (5’-AGCTTCAATCTTCAGGAT-3’) and were manufactured by Wuhan servicebio Technology. Slides were incubated with probe diluted in prewarmed hybridization buffer overnight at 40 °C in a humid chamber. Slides were subsequently washed three times with pre-warmed (37 °C) washing buffer and Tris buffer, respectively. Tissues were stained by DAPI, and fluorescent signal capture using a confocal microscope (NIKON ECLIPSE CI, Japan). The fluorescence intensity of all the samples was evaluated using the ImageJ Fiji, and statistical analysis was performed.

CCK8 assay

IHH4 and TPC1 cells were stimulated by bacteria as described above. Then cell growth was assessed using the CCK8 assay. Briefly, IHH4 and TPC1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (2 × 103 cells/well). The culture medium was removed the next day and 100 uL fresh medium containing 10 µL CCK8 solution were added to each well. After 1 h incubation, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Migration and invasion assays

Tumor cells invasion and migration assays were carried out in Transwell chambers (Corning, #3422) with or without Matrigel® Basement Membrane Matrix (Corning, #356234). 200 µL cells in DMEM (FBS-free, 1% P/S) were seeded in the upper chamber (2 × 105 cells /well), with the bottom chamber filled with 600 μL DMEM (10% FBS, 1% P/S). After 24 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and stained with 0.2% crystal violet for 30 min. Images of invaded or migrated cells were captured from five random fields per condition with a microscopy. The bound crystal violet was eluted by adding 33% acetic acid into each insert and shaking for 10 min. The eluent from the lower chamber was transferred to a 96-well clear microplate, and the absorbance value (optical density, OD) at 570 nm was measured using Thermo Scientific Microplate Reader.

Western blot

Western blot was performed as previously described37. Tumor tissues and cell pellets were lysed using RIPA buffer (Beyotime, #P0013B) and protein concentration was quantified using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermofisher, #23227). GAPDH was used as an endogenous control. The following antibodies were used: anti-E-Cadherin (CST, #3195 T, 1:1000 dilution), anti-Vimentin (CST, #5741 T, 1:1000 dilution), GAPDH (CST, #2118 T, 1:1000 dilution), anti-N-Cadherin (CST, #13116 T, 1:1000 dilution), anti-β-catenin (CST, #8480 T, 1:1000 dilution), anti-c-MYC (CST, #5605 T, 1:1000 dilution).

β-catenin gene silencing

Lentiviruses were generated by co-transfecting HEK293T cells with packaging plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G) using PEI MAX 40 K (Polyscience, Illinois, USA), and viral supernatants were collected after 48 h. Then, the virus-containing medium supernatants were used to infect IHH4 and TPC1 tumor cells using polybrene (1 μg/ml) methodology. Puromycin-resistant IHH4 cells (Puromycin, 1.5 μg/ml) and TPC1 cells (Puromycin, 2 μg/ml) were selected for the subsequent experiment. All shRNA sequences are listed as follows: shCTL: TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT, shβ-catenin#1: GCACAAGAATGGATCACAAGA, shβ-catenin#2: GCTGGTATCTCAGAAAGTGCC.

Bacteria culture and identification

Isolation of anaerobic or aerobic bacteria was performed as previously described. 100–200 mg tumor tissues were cut into pieces and homogenized in 1 mL ice-cold BHI under sterile conditions. 1×PBS was used as NTC and went through the same workflow to evaluate the environmental contaminants. For aerobic culture, 200 uL sample homogenate was plated on BHI plates at 37 °C aerobically with 5% CO2.

For anaerobic culture, 200 uL sample homogenate was transferred to 5 mL BHI medium and cultured under anaerobic conditions for 2 days for bacterial enrichment, then 20 uL culture medium were plated on brucella broth agar plates (Bruce, BD, #211088) supplemented with 5% sheep citrated blood. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 5 days in anaerobic conditions.

For identification of bacteria strain, colonies were picked and streaked in designated plate and condition for 1–3 days to get single colony. The single colony was picked to grow in plates and run colony PCR subsequently. Briefly, the 20 uL reaction mix contained 1 uL bacteria DNA, 8 uL steriled enzyme-free water (Solarbio, #R1600–500 ml), 10 uL 2× Taq plus MasterMix II (Dye plus) (Vazyme, #P213-03) and 0.5 uL forward primer (27 F: 5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’), 0.5 uL reverse primer (1492 R: 5’-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’). The reaction was programmed according to the reagent instructions. The PCR product was sent out for sequencing and the sequencing results were aligned to the 16S rRNA sequences database in the NCBI BLAST site.

High throughput 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals). In brief, barcoded amplicons from the V3-V4 region were generated using PCR. In the first step, 10 ng genomic DNA was used as template for the first PCR with a total volume of 20 μL using the 338 F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’) and 806 R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) primers appended with Illumina adaptor sequences. Subsequently, PCR products were purified, checked on a Fragment analyzer and quantified, followed by equimolar multiplexing, and sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform (2 × 300 bp). Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME2) software was used for microbial analyses. Reads were imported, quality filtered and demultiplexed with the q2-data2 plugin. The sequences were classified using Greengenes (version 13.8) as a reference 16S rRNA gene database. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA), Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) and Significant Species were performed using R (v4.1.1). 16S rDNA data are available from the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa) under accession number PRJCA022672.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analysis and data visualization carried out in this study was performed by GraphPad Prism 8. The data were presented as means ± SEM. Differences between two groups were compared using unpaired Student’s t-tests. Comparisons among three or more groups were performed by one-way ANOVA test combined with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Differences in clinical characteristics of patients were determined using Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. All p values were two-tailed, and differences with a p value less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses