Ca2+-triggered allosteric catalysts crosstalk with cellular redox systems through their foldase- and reductase-like activities

Introduction

Metabolic disorders in living cells lead to undesired chemical phenomena such as oxidative stress1,2,3, protein misfolding4,5, glycative stress6,7, and nucleic acid modification8,9,10, eventually causing irreversible cellular pathological degeneration. Chemical small molecules would be useful for artificially regulating cellular homeostasis by aiding and enhancing the functions of enzymes, which are responsible for the order of intracellular chemical reactions. This approach can expand the range of therapeutic strategies for various diseases. Although small organocatalysts with enzyme-like functions, such as small catalysts with high reactivity, have been developed in recent decades, they often cause nonspecific reactions in cells, leading to catalyst inactivation and cytotoxicity11. Therefore, novel biocompatible molecules that incorporate the spatiotemporal concept are needed to exert appropriate physiological activity at appropriate times in specific cellular compartments.

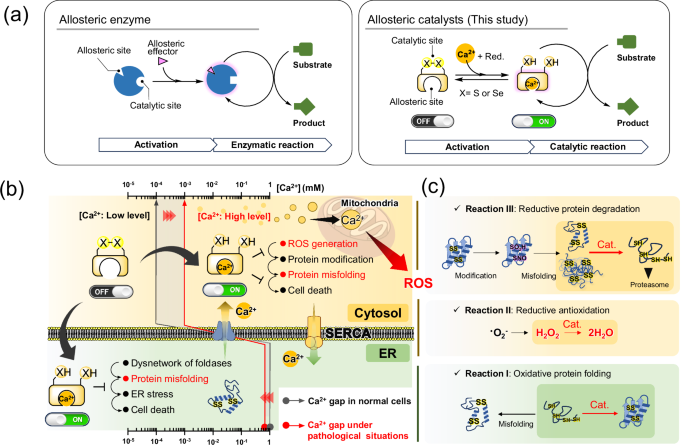

Allosteric enzymes, which are responsible for the space-time dynamics of intracellular reaction fields, are representative biomolecular machinery that modulate the intensity of catalytic activities and substrate selectivity in response to their own structural changes triggered by allosteric effectors (Fig. 1a, left)12. Controlling a reaction system consisting of multiple elementary reactions is typically difficult, even in a flask where the solvent, additive, and temperature can be changed arbitrarily. Nonetheless, several catalysts that mimic the functions of allosteric enzymes have been developed in recent years, enabling better control of complex reaction systems in flasks13,14,15,16. These catalysts can modulate their catalytic activities by changing their molecular structure in response to external stimuli (e.g., light, temperature, pH, and ion strength) and promote or inhibit a specific reaction. However, the application of artificial catalysts has been largely limited to reactions in organic solvents17. Although numerous studies have focused on overcoming this issue18,19,20, in-cell-driven allosteric catalysts that crosstalk with biological phenomena in living cells have not been explored.

a Action of enzyme (left) and an artificial enzyme-like catalyst (right) regulated by an allosteric effector. b Crosstalk between Ca2+-triggered allosteric S–S- or Se–Se-catalyst and redox imbalance induced by abnormal fluctuation of the Ca2+ concentration. c Model bio-related redox reactions (I–III) up- and downregulated by Ca2+-triggered catalysts.

Redox reactions are essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis. An imbalance in the redox system in cells leads to the production of pathogenic substances such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and misfolded proteins21,22. Thiolate (S−) and selenolate (Se−) anions, which are the deprotonated states of cysteinyl thiol (SH) and selenocysteinyl selenol (SeH), respectively, act as excellent two-electron donors at the active centers of various oxidoreductases. We previously developed small SH- and SeH-based catalysts that mimic the activities of oxidoreductases involved in oxidative folding 23,24,25,26,27 and reductive antioxidation28,29. Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident oxidoreductase that catalyzes folding coupled with disulfide (S–S) bond formation between Cys residues (oxidative folding) in nascent polypeptides30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Two CGHC tetrapeptides, which constitute the catalytic sites in PDI, catalytically isomerize mis-bridged S–S bonds in substrate proteins to the correct S–S-bonding pattern found in the native state through their high nucleophilic capability of cysteinyl SH groups (for more information on the catalytic mechanisms of PDI, see Results). In the presence of a reducing agent, trans-4,5-dihydroxy-1,2-dithiane (DTTox)37 and its diselenide (Se–Se) analog (DSTox)23 are reversibly activated into the ring-opened states, DTTred and DSTred, respectively (Fig. 2a, left). These structures promote S–S isomerization during oxidative folding through a molecular mechanism similar to that of PDI. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) is a representative selenoenzyme with a selenocysteine residue in the active center, which catalytically reduces hydroperoxides with glutathione (GSH) as a co-substrate38,39. DSTred shows much higher GPx-like activity than does DTTred because the SeH group has a higher electron-donating capacity than that of the SH group29,40. Organochalcogenic compounds are promising surrogates for oxidoreductases that maintain cellular redox homeostasis41. However, such reagents, which are highly reactive but nonspecific, are often cytotoxic. Consequently, they have been applied to in-cell and in vivo experiments in only a few cases42,43.

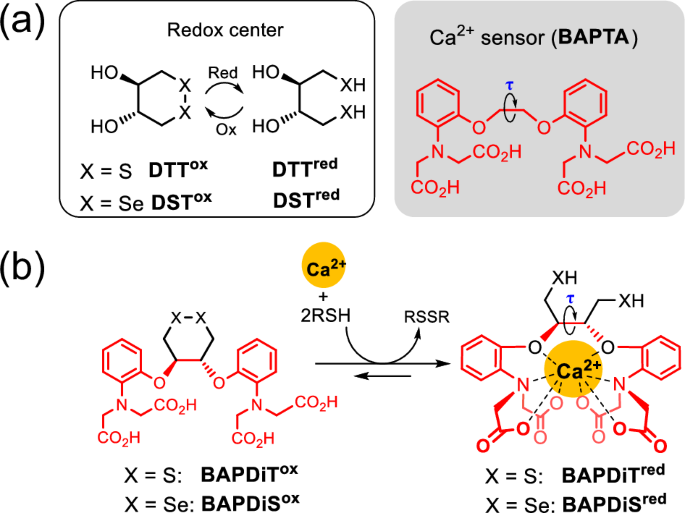

a Molecular structure of DTTox/red, DSTox/red and BAPTA as a Ca2+-selective chelator. b BAPTA-fused DTTox and DSTox, namely BAPDiTox and BAPDiSox, respectively, which can be activated to the corresponding chalcogenol states in the presence of Ca2+.

To ensure that our established minimal oxidereductase-like catalysts can appropriately exhibit high activity in specific situations, we fused them with an activity-switching sensor (Fig. 1a, right). Several metal ions are abundant and ubiquitous in cells, and their concentrations vary widely and reversibly in signaling pathways. Hence, the quantitative properties of metal ions may be useful as triggers to turn the activity of the artificial catalyst in cells on or off. After K+ and Na+, Ca2+ is among the most abundant metal ions in mammals and is closely related to various biological redox reactions. In the ER, which stores high concentrations of Ca2+ (approximately 1 mM) (Fig. 1b, green), Ca2+-binding chaperones such as calnexin and calreticulin control the quality of nascent proteins by cooperating with S–S-related oxidoreductases (i.e., PDI family proteins)44,45,46,47. Abnormal fluctuations in Ca2+ concentrations in the ER cleave the cross-network between ER-resident enzymes and contribute to the generation of misfolded proteins, eventually causing various human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders (Fig. 1b, green)48,49,50. In addition, excessive release of Ca2+ from the ER into the cytosol increases the mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration via Ca2+-transportation systems, such as the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter, eventually leading to ROS production and subsequent oxidative modification and misfolding of proteins (Fig. 1b, yellow)51,52.

In this study, we synthesized allosteric S–S- and Se–Se-based redox reagents and catalysts that modulate their activity in response to a change in the Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 2b) (see the next section for the design concept). Subsequently, we demonstrated in vitro up- and downregulation of kinetics for three representative bio-related redox reactions: (I) oxidative protein folding, (II) reductive antioxidation, and (III) reductive protein degradation, using synthetic allosteric catalysts (Fig. 1c). Finally, we conducted in-cell investigations to demonstrate that allosteric catalysts can contribute to redox homeostasis and protect against redox imbalance induced by fluctuations in Ca2+ concentrations in living cells.

Results

Synthesis of allosteric catalysts

The ethylene glycol derivative, 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA, Fig. 2a, right), rigidly forms a symmetric octa-coordination complex with Ca2+ 53. In this study, we synthesized BAPDiTox and BAPDiSox, which are the DTTox and DSTox analogs, respectively, with the BAPTA moiety as the Ca2+-capturing site (Fig. 2b). The dihedral angle (τ) in the ethylene glycol moiety of BAPTA is firmly fixed by coordinating Ca2+ to its ligand (Fig. 2a, right)54. Incorporation of Ca2+ into the ligands of BAPDiTox and BAPDiSox is expected to cause substantial strain in the cyclic structures, resulting in thermodynamically destabilized S–S and Se–Se bonds, which are readily converted to the corresponding reactive reduced states in the presence of reductants (Fig. 2b).

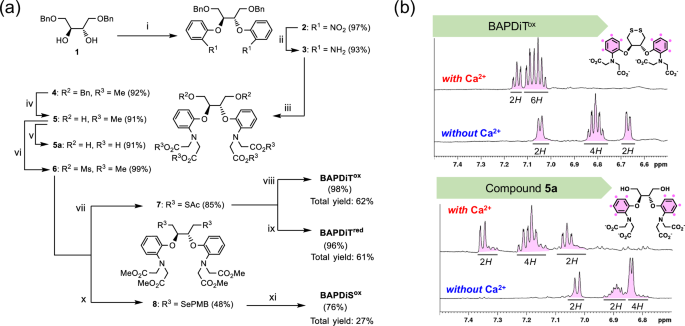

BAPDiTox and its reduced form (BAPDiTred) were synthesized in total yields of 62% and 61%, respectively, in seven steps (Fig. 3a). A similar protocol was adopted to obtain BAPDiSox, which resulted in 27% overall yield over seven steps. However, the reduced form of BAPDiSox (BAPDiSred) could not be isolated because of its instability in air. All synthesized compounds were identified via spectroscopic analyses using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry (see Supplementary Information). To monitor the Ca2+-coordinating behavior of the compounds, BAPDiTox was mixed with Ca2+ in buffer solution at pH 7.5, and the resulting solution was analyzed using 1H NMR (Fig. 3b). The NMR spectra showed that addition of Ca2+ changed the signals corresponding to the protons of the two aryl groups (Fig. 3b, top panels) in terms of both the chemical shift and coupling state. This result indicates that the structure and electronic state of the ligand were dramatically changed by coordination of Ca2+. Similar spectral changes were observed for compound 5a, an inactive model compound of BAPDiTred and BAPDiSred (Fig. 3b, bottom panels). Furthermore, 13C NMR spectroscopic analysis of BAPDiTox indicated that incorporation of Ca2+ into the ligand caused a structural change in the cyclic skeleton (Supplementary Fig. 1), strongly supporting that Ca2+ can function as an allosteric effector.

a Synthetic routes for BAPDiTox, BAPDiTred, and BAPDiSox. Starting material 1 was prepared in 51% overall yield through 3 steps as described previously (see Supplementary Information). Reaction conditions: (i) NaH and 2-fluoronitrobenzene in dimethylformamide (DMF) at 120 °C for 19 h; (ii) Zn and acetic acid (AcOH) in tetrahydrofuran (THF)/methanol (MeOH) at 25 °C for 17 h; (iii) NaI, proton sponge, and methyl bromoacetate in CH3CN for 16 h under the reflux condition; (iv) H2 and Pd/C in MeOH at 25 °C for 22 h; (v) KOH in THF/MeOH at 25 °C for 2 h; (vi) MsCl in pyridine at 0 °C for 2 h; (vii) KSAc in DMF at 60 °C for 2 h; (viii) KOH in THF/MeOH at 25 °C for 3 h, and then H2O2 at 25 °C for 0.5 h; (ix) KOH in THF/MeOH at 25 °C for 3 h, and then TCEP at 25 °C for 1 h; (x) (PMBSe)2 and NaBH4 in THF/EtOH for 2.5 h under the reflux condition; (xi) I2 in MeOH/H2O at 25 °C for 2 h, and then KOH in THF/MeOH. b 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of compound 5a as a chain-opened model and BAPDiTox as a chain-closed model in the presence or absence of Ca2+ at pH 7.5 and 25 °C. Reaction conditions: for bottom panels, CaCl2 (97 μmol) was added to solution of compound 5a (9.7 μmol) in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer solution at pH 7.5 (400 μL); for top panels, CaCl2 (90 μmol) was added to solution of BAPDiTox (9.0 μmol) in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer solution at pH 7.5 (400 μL). 1H NMR (500 MHz) spectra were recorded at 25 °C using a double sample tube, which comprised of an inner and outer tube including D2O and the sample solution, respectively.

Physicochemical properties of the allosteric catalysts

To quantify the allosteric effects of the synthesized compounds, their physicochemical properties in the presence and absence of Ca2+ were investigated. First, to evaluate the effect of Ca2+ on thermodynamic stability of the S–S and Se–Se bonds, their reduction potentials were measured using the redox equilibrium reaction between the compounds and DTTred (Supplementary Fig. 2). In both BAPDiT and BAPDiS measurements, addition of Ca2+ to the sample solution significantly increased the reduction potential (Table 1). This result indicated that Ca2+ coordination induced ring-distortion in the oxidized forms and limited rotation of the dihedral angle (τ) in the reduced forms (Fig. 2b), thereby decreasing the relative thermodynamic stability of the S–S and Se–Se bonds. Thus, the redox capabilities of BAPDiT and BAPDiS may be up- and downregulated in situ by changing the concentration of Ca2+ as an allosteric effector. Furthermore, the dependency of the reduction potential on the Ca2+ concentration was investigated using BAPDiSox. The estimated reduction potential of BAPDiSox was plotted against the Ca2+ concentration (Supplementary Fig. 3). The results indicated that for concentrations up to the 1/100 equivalent of CaCl2 with respect to BAPDiSox, the reduction potential did not significantly increase, and that 1 to 10 equivalents of Ca2+ were required to sufficiently destabilize the Se–Se bond. In contrast, Mg2+, a homologous divalent ion of Ca2+ that is abundant in living cells, did not increase the reduction potential of the compounds, suggesting that the compounds can selectively chelate Ca2+. Supplementary Fig. 12 further shows the ion selectivity of the compounds. In addition, the average pKa values of the two SH groups in BAPDiTred were almost identical in the presence and absence of Ca2+, indicating that Ca2+ did not affect the acidities (nucleophilicities) of the chalcogenol groups (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Kinetics of biological redox reactions controlled by the allosteric catalysts

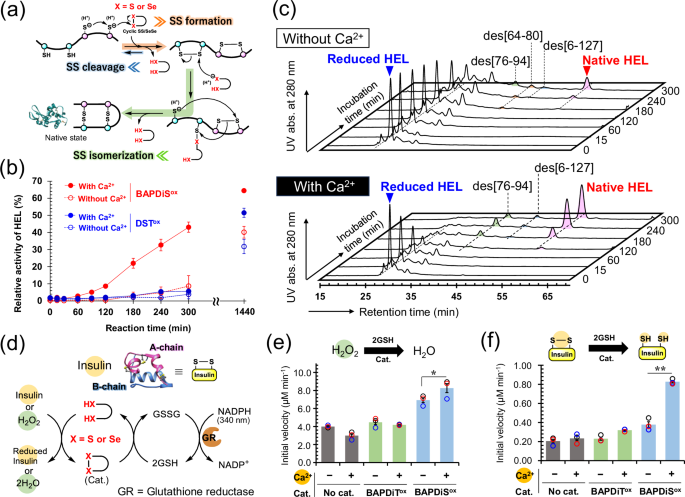

We further attempted to control the kinetics of the biological redox reactions in buffer solution by utilizing the redox tunability of BAPDiT and BAPDiS. First, the oxidative folding (Reaction I in Fig. 1c) of the reduced form of hen egg white lysozyme (HEL), which has four S–S bonds (i.e., C6‒C127, C30‒C115, C64‒C80, and C76‒C94) in the native state, was performed using the synthetic compounds as catalysts in the absence or presence of Ca2+. Oxidative folding involves two chemical processes, namely S–S formation and subsequent S–S isomerization (Fig. 4a). During S–S formation, oxidation occurs in protein molecules to form non-native (mis-bridged) S–S bonds. In contrast, during S–S isomerization, rearrangement occurs to form the correct S–S bonding pattern found in the native state. The cyclic S–S and Se–Se moieties in the compounds promote oxidative folding in a manner similar to the catalytic mechanism of PDI. Briefly, S–S and Se–Se introduce S–S linkages into a substrate protein via an intermolecular bond exchange reaction (Fig. 4a; arrow highlighted in orange), whereas the SH (S–) and SeH (Se–) groups in BAPDiTred and BAPDiSred, respectively, temporarily cleave misbridged S–S bonds to exchange the S–S positions via a mixed S–S or S–Se intermediate (Fig. 4a; arrows highlighted in green). Here, reduced HEL was incubated with BAPDiSox under aerobic conditions. During oxidative folding, populations of bioactive species, including native HEL, gradually increase. Thus, the progression of oxidative folding can be estimated indirectly by estimating the relative enzymatic activity in a sample solution. The recovery of HEL enzymatic activity was estimated at specific time points, as described previously (Fig. 4b)25. Although the recovery of enzymatic activity was negligible in the absence of Ca2+, the coexistence of Ca2+ dramatically accelerated the catalytic oxidative folding, yielding 45% of the active HEL after 5 h. Furthermore, Ca2+ concentration-dependency on foldase-like function of BAPDiSox was also evaluated. When the oxidative folding of HEL was performed in the presence of various concentrations of Ca2+, the foldase-like activity of BAPDiS was gradually enhanced with increasing Ca2+ concentration (Supplementary Fig 5). In contrast, DSTox, which has no Ca2+ ligand, did not mediate HEL folding in neither the presence nor absence of Ca2+. These observations indicate that incorporating Ca2+ into the compound ligand causes upregulation of cyclic Se–Se catalytic activity for oxidative folding. Slow oxidative folding typically reduces the yield of the native state because of competitive aggregation of structurally immature folding intermediates. Interestingly, when BAPDiSox was used as a catalyst in the presence of Ca2+, up to 64% the enzymatic activity was recovered after 24 h, whereas under other conditions, the recovery was only 30–50%. Improved folding kinetics may have shortened the lifetime of structurally immature folding intermediates, suppressing undesired protein aggregation and resulting in higher final folding yields.

a General oxidative folding mechanisms. b Time course of recovered enzymatic activity of HEL during oxidative folding of reduced HEL using BAPDiSox (red) or DSTox (blue) as a catalyst in the presence (solid line) or absence (dashed line) of Ca2+. Reaction conditions: [reduced HEL]0 = 10 μM, [BAPDiSox]0 or [DSTox]0 = 20 μM in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer solution containing no or 1 mM CaCl2 at 37 °C and pH 7.5 in the presence of 2 M urea under aerobic conditions. Data are shown as the means ± SEM (n = 3). c High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) chromatograms obtained from oxidative folding of reduced HEL using BAPDiSox in the absence (top) or presence (bottom) of Ca2+. The reaction conditions were the same as those in (b). Des intermediates, des[6-127], des[64–80], and des[76–94], represents key precursors of native HEL having three native S–S bonds but lacking one S–S linkage denoted in the brackets65,66,67. d Reductase-like function of compounds for reduction of H2O2 and protein S–S bonds coupled with NADPH oxidation. e Comparison of initial velocity for catalytic reduction of H2O2. Reaction conditions: [H2O2]0 = 0.25 mM, [GSH]0 = 4.0 mM, [NADPH]0 = 0.3 mM, [GR] = 4 unit mL−1, and [Cat.] = 0.1 mM at 25 °C and pH 7.2 in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer solution containing 0.9 mM EDTA with or without 1.83 mM CaCl2. f Comparison of initial velocity for catalytic reduction of S–S bond in insulin. Reaction conditions: [insulin]0 = 60 μM, [GSH]0 = 3.7 mM, [NADPH]0 = 0.12 mM, [GR] = 4 unit mL−1, and [Cat.] = 30 μM at 25 °C and pH 7.2 in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer solution containing 0.9 mM EDTA with or without 1.83 mM CaCl2.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of the folding intermediates generated during the reaction was performed to further understand the oxidative folding of HEL (Fig. 4c). The HPLC chromatograms showed that the presence of Ca2+ in the sample solution substantially accelerated both the oxidation of reduced HEL and subsequent generation of native HEL. This result suggests that BAPDiSox, whose oxidizability was enhanced by incorporation of Ca2+, promoted S–S formation in the substrate protein and BAPDiSred, which was generated in the solution, catalyzed S–S isomerization to form the correct S–S-bonding pattern (Fig. 4a). Similar enhancement of oxidative folding in the presence of Ca2+ was observed in experiments using BAPDiT (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Notably, oxidative folding promoted by BAPDiT and BAPDiS with Ca2+ was decelerated by addition of EDTA, a non-specific chelator of divalent metal ions, and re-accelerated upon further Ca2+ addition (Supplementary Fig. 6b, c). Thus, the kinetics of oxidative folding mediated by synthetic compounds may be precisely controlled using Ca2+ as a trigger switch.

To further explore the functions of the synthesized compounds, we evaluated their reductase-like activity against ROS (Reaction II in Fig. 1c) and protein S–S bonds (Reaction III in Fig. 1c). In these assays (Fig. 4d), cyclic S–S or Se–Se is converted by coexisting GSH into the corresponding dithiol and diselenol states, which then reduce H2O2 or insulin S–S bonds as substrates through GPx- and PDI-like functions, respectively 55,56. Generated oxidized GSH (GSSG) is quickly reduced back to GSH with NADPH by glutathione reductase. Thus, the reductase-like activity of the compounds was evaluated by monitoring changes in absorbance at 340 nm due to consumption of NADPH.

In the reduction of H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b), BAPDiTox did not promote the reaction in the presence and absence of Ca2+. In contrast, the initial velocity increased by 1.7-fold in the presence of BAPDiSox, a selenium analog, compared with that observed in the control sample in the absence of the catalyst (Fig. 4e). These trends were not consistent with the order of the reduction potentials of the compounds. This result suggests that not only the thermodynamics of the S–S and Se–Se bonds, but also the kinetics for activation to the chalcogenol forms is an important determinant of the catalytic reaction velocity 28. More importantly, addition of Ca2+ further enhanced the initial reaction velocity by 1.1-fold compared with that observed in the absence of Ca2+ (blue bars in Fig. 4e). Furthermore, the catalytic activity of BAPDiSox was enhanced with increasing Ca2+ concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 7c). This result suggests that Ca2+ functioned as an allosteric effector and assisted in ring-opening of the cyclic Se–Se bond with GSH, resulting in enhanced catalytic function. Nevertheless, Ca2+ only slightly increased reactivity, likely because another catalytic pathway involving direct reduction of H2O2 by Se–Se (i.e., -Se–Se – + H2O2 → -Se(=O)–Se- + H2O [Supplementary Fig. 8]) was dominant in this reaction, as reported previously29. A similar trend was observed in catalytic reduction of H2O2 using DTTred as the thiol co-substrate instead of GSH (Supplementary Fig. 9).

To further evaluate the function of allosteric compounds as reductase-like catalysts, catalytic S–S reduction was monitored using insulin as a model substrate (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). Similar trends to those observed in the catalytic reduction of H2O2 were observed, but the reactivity enhancement by Ca2+ was more dramatic. Namely, addition of Ca2+ enhanced the initial reaction velocity by more than two-fold (blue bars in Fig. 4f). In addition, the catalytic activity of BAPDiSox was enhanced with increasing Ca2+ concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 10c). This trend is consistent with that observed for Ca2+ concentration-dependency on the reduction potential of BAPDiSox (Supplementary Fig. 3). This result indicates that Ca2+ can also upregulate the S–S-reductase-like activity of BAPDiSox.

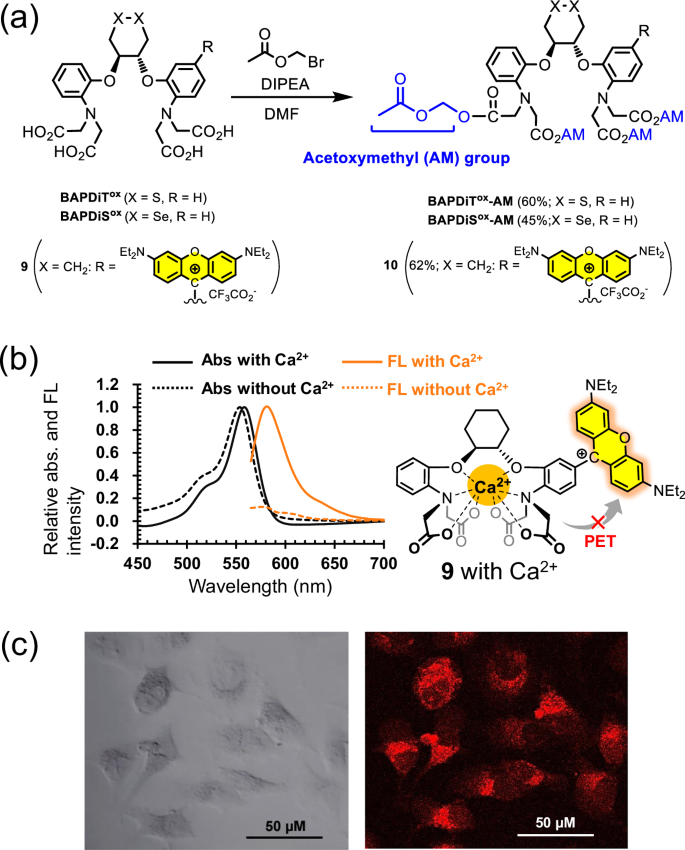

Ca2+-association of the allosteric catalysts in living cells

Taking advantage of the redox tunability of BAPDiSox and BAPDiTox, these compounds may be applied as biocompatible allosteric catalysts that exhibit oxidoreductase-like activity only under specific physiological conditions in cells (Fig. 1b). To allow BAPDiTox and BAPDiSox to permeate the cell membrane, these compounds were treated with bromomethyl acetate, thereby protecting the four carboxylic groups with acetoxymethyl (AM) esters (Fig. 5a). The AM-protected compounds, BAPDiTox-AM and BAPDiSox-AM, are hydrolyzed by cytosolic esterases after penetrating cells (Supplementary Fig. 11), and then the allosteric effect should be induced by chelating intracellular Ca2+. To confirm the Ca2+-chelating behavior of BAPDiTox and BAPDiSox in living cells, a redox-inactive model compound 9 with a rhodamine-type chromophore group was also synthesized (see Supplementary Information for synthesis details). Compound 9 emitted strong orange-yellow fluorescence at 580 nm under excitation at 558 nm because of inhibition of photoinduced electron transfer (PET57,58) by incorporating Ca2+ into the ligand (Fig. 5b). Other chemical properties of this compound, such as the dissociation constant (Kd) and metal ion selectivity, are summarized in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13 and Supplementary Table 1). HeLa cells were cultured in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 10, which is AM-protected 9 (Fig. 5a), in the presence of Pluronic® F-127 for 30 min. After replacing the medium with HBSS containing Ca2+ and culturing the cells for 30 min, fluorescence imaging was performed using a confocal fluorescence microscope. Fluorescence staining of HeLa cells clearly indicated that compound 9, which was generated by hydrolysis of 10 in the cells, captured intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 5c). In addition, when BAPTA-AM was subsequently added to the medium, the fluorescence intensity significantly decreased (Supplementary Fig 14), suggesting that BAPTA withdrew Ca2+ from compound 9 in cells and/or reduced the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. This model study supports that the fluorescence depends on intracellular Ca2+ and indicates that BAPDiTox and BAPDiSox could also capture intracellular Ca2+ via their BAPTA-type ligand.

a Modification of BAPDiTox, BAPDiSox, and fluorescent compound 9 to acetoxymethyl (AM)-protected compounds. b Absorption spectra of compound 9 (5 μM) in the absence (black dashed line) and presence (black solid line) of Ca2+ (30 μM) and fluorescence emission spectra of compound 9 (5 μM) in the absence (orange dashed line) and presence (orange solid line) of Ca2+ (30 μM). The spectra were recorded using a quartz cell (path length = 10 mm) under excitation at 550 nm. The samples were prepared in 50 mM HEPES buffer solution (pH 7.5) with or without Ca2+. c Bright-field (left) and confocal fluorescence (right) microscopy images of HeLa cells incubated with compound 10 (2.0 μM) (λex = 561 nm; λem = 570–620 nm).

Crosstalk of allosteric catalysts with cellular redox systems

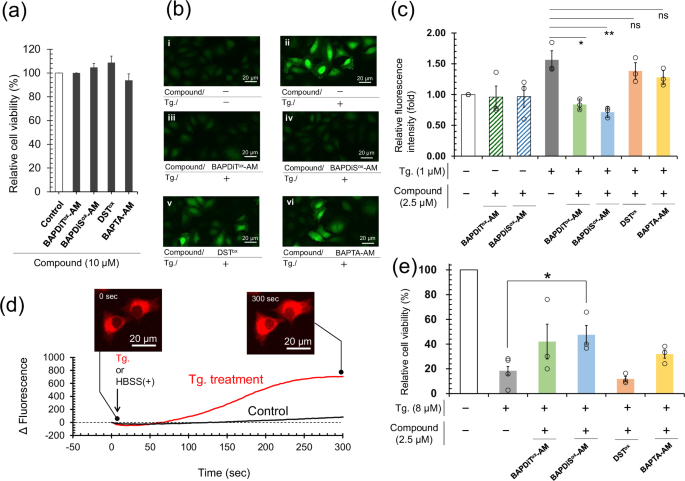

We examined the potential contributions of BAPDiTox-AM and BAPDiSox-AM to cellular homeostasis maintenance involving biological redox reactions. DSTox with no Ca2+ ligand and AM-protected BAPTA (BAPTA-AM) with no redox site were used as reference samples. When HeLa cells were cultured with different concentrations of the synthetic compounds, no cytotoxicity was observed at concentrations up to 10 μM, suggesting that the compound did not adversely affect the steady-state of living cells (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 15).

a Cytotoxicity of compounds at 10 μM determined using MTT assay with HeLa cells (1 × 104 cells/well) cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 15 h. Each independent experiment was performed in triplicate. All data of bars are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). b Confocal laser scanning microscopic images of HeLa cells. HeLa cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were treated with Tg (1 μM or none) for 1 h after pretreatment with the synthetic compounds (2.5 μM or none) for 1 h and then stained with highly sensitive DCFH-DA dye® by according to the manufacturer’s protocol. c Quantitative estimation of ROS levels in HeLa cells using a fluorescence microplate reader (excitation: 500 nm, emission: 530 nm). Stained HeLa cells were obtained using the same protocol as those in (b). Each independent experiment was performed in triplicate. White and gray bars are positive and negative control groups, respectively. All data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). P value was obtained using t test. d Change in fluorescent intensity observed through time-laps analysis using a confocal laser scanning microscope. HeLa cells (3 × 105 cells) seeded in a dish (φ 35 mm) that had been preincubated with compound 10 (2 μM) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 1 h were stimulated with or without Tg (1 μM). e Cell viability of HeLa cells (1 × 104 cells/well) incubated with Tg (0 or 8 μM) for 20 h after pretreatment with the synthetic compounds (0 or 2.5 μM) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 1 h. Cell experiments were performed at least three times. Each independent experiment was performed in triplicate. White and gray bars are positive and negative control groups, respectively. All data are shown as the mean ± SEM. P value was obtained using student’s t test.

Subsequently, to evaluate the function of BAPDiTox and BAPDiSox as alternative molecules for PDI in the ER, HeLa cells were incubated for 24 h in medium containing 2-[[4-(cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazin-1-yl]methyl]-1,2-benzothiazol-3-one (LOC1459), a potent inhibitor of PDI (see Supplementary Fig. 16a for cytotoxicity examination of LOC14), along with compound (10 or 50 µM). The 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay showed that cell viability was not improved following BAPDiTox-AM and BAPDiSox-AM treatments (Supplementary Fig. 17), presumably because anionic BAPDiTox and BAPDiSox, which are generated by cytosolic hydrolysis of AM-protected compounds, cannot penetrate the ER membrane. Alternatively, these compounds may not be active enough in the intracellular environment to maintain the quality control of proteins in the ER but can exhibit good PDI-like activity under optimized conditions in a test tube (Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 6). Interestingly, DSTox, an electrically neutral compound, significantly improved cell viability (Supplementary Fig. 17). However, further analyses are necessary to identify the molecular mechanisms by which DSTox suppresses cell death.

Next, to validate the reductase-like activity of the synthetic compounds in living cells, oxidative stress was induced by inhibiting sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA). SERCA is a typical P-type ATPase present in the ER membrane that pumps Ca2+ from the cytosol, where Ca2+ is present at low concentrations (< 100 nmol), to the ER against the Ca2+ concentration gap60,61. SERCA dysfunction leads to an abnormal increase in cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations through several pathways involving the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter and mitochondria-associated ER membranes and subsequent overproduction of ROS via mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. 1b)52. This process is closely associated with several chronic diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, and muscular dystrophy62. Synthetic compounds that exhibit remarkable foldase- and reductase-like activity only in the presence of Ca2+ as a trigger switch have ideal chemical properties to resist SERCA-related diseases, both in terms of regulation of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and redox control.

HeLa cells preincubated in medium with or without the compounds (2.5 µM) were treated with thapsigargin63 (Tg; 1 µM), a potent inhibitor of SERCA (see Supplementary Fig. 16b for cytotoxicity examination of Tg). Cellular ROS levels were measured using DCFH-DA dye® (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). Treatment of HeLa cells with Tg substantially increased ROS levels, as evidenced by an increase in fluorescence intensity (Fig. 6b-ii). In contrast, pretreatment of cells with BAPDiTox-AM and BAPDiSox-AM suppressed the increase in fluorescence intensity (Fig. 6b-iii and 6b-iv). Notably, DSTox and BAPTA-AM, which lack the ligand for Ca2+ and redox site, respectively, were less capable than BAPDiTox-AM or BAPDiSox-AM in reducing ROS levels (Fig. 6b-v and -vi).

To quantify total ROS levels, the fluorescence intensity of the cultured HeLa cells was measured using a fluorescence microplate reader. The results confirmed that BAPDiTox-AM and BAPDiSox-AM effectively suppressed the Tg-induced increase in ROS levels in HeLa cells (green and blue bars in Fig. 6c). Notably, pretreatment with BAPDiTox-AM and BAPDiSox-AM did not change the total ROS level in cells at steady-state compared to that in the control group (white bar vs striped bars in Fig. 6c), indicating that the compounds did not affect the steady redox status in living cells. Although DSTox and BAPTA-AM slightly decreased ROS levels, their effects were modest (orange and yellow bars in Fig. 6c). The sum of ROS levels reduced by DSTox and BAPTA-AM was significantly smaller than that observed for BAPDiTox-AM and BAPDiSox-AM. This result indicated that the remarkable ROS-reducing capability of BAPDiTox-AM and BAPDiSox-AM was conferred by the synergetic effect of fusion of the Ca2+ ligand and redox active site. Compound 10, a redox-inactive model compound for BAPDiTox-AM and BAPDiSox-AM, increased its own fluorescence intensity with increasing cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, which was induced by SERCA inhibition with Tg (Fig. 6d). Collectively, these observations provide circumstantial evidence that the cyclic S–S or Se–Se moiety, which is allosterically activated by chelating Ca2+ into the ligand, regulates the cytosolic redox balance, possibly through its reductase-like activity, as shown in Fig. 4e, f. Moreover, BAPDiTox-AM and BAPDiSox-AM were mostly inactive against oxidative stress in HeLa cells directly induced by H2O2 treatment, implying that a high level of Ca2+ in the cytosol is essential for the compound’s reductase-like activities (Supplementary Fig. 18).

However, in assessment of hydroperoxidase-like activity, Ca2+ did not substantially increase the activity of BAPDiSox (Fig. 4e). This result implies that the compounds mainly act as S–S-reductase-like catalysts, indirectly enhancing the intracellular antioxidative potential by activating cytosolic antioxidant enzymes, such as glutaredoxin and thioredoxin, with Cys-Xaa-Xaa-Cys (Xaa = an amino acid) motifs in their active centers, rather than directly scavenging ROS through hydroperoxide-like functions. In contrast to our initial assumption, BAPDiTox, which was inactive in the hydroperoxide- and S–S-reductase-like activity assays (Fig. 4e, f), was also effective in regulating the redox balance in HeLa cells. This result suggests that the S–S and Se–Se bond thermodynamics of the compounds (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2c) is responsible for regulating the redox balance in cells, whereas the kinetics for active chalcogenol state generation is a major determinant of the catalytic reaction rate (Fig. 4e, f). Importantly, when HeLa cells pre-incubated with BAPDiSox-AM for 1 h were treated with Tg for 22 h, cell viability was significantly improved compared with that in the control group (Fig. 6e). Our observations suggest that the allosteric redox compounds proposed in the present study are candidate therapeutic agents for a variety of diseases associated with redox imbalance induced by SERCA pump dysfunction. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the molecular mechanisms in greater detail.

Discussion

Through molecular design of cyclic S–S/Se–Se compounds fused with BAPTA-type ligands, we developed artificial allosteric redox catalysts activated by Ca2+ as a trigger switch. Selective incorporation of Ca2+ into the ligand led to a strain of cyclic dichalcogenide, which was readily converted into the corresponding highly reactive chain-opened dichalcogenols possessing reductase and foldase activities. By adjusting the concentration of Ca2+ in the solution, the kinetics of the three model reactions (Fig. 1c), oxidative protein folding, reductive antioxidation, and reductive protein degradation, were precisely controlled. At a low Ca2+ concentration, the compound existed as an almost stable dichalcogenide (OFF state, Fig. 1b) and therefore did not affect homeostasis in normal cells. In contrast, in specific situations where cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations were elevated, the compounds were converted into the activated state (ON state, Fig. 1b) because of their allosteric effect and resisted the redox imbalance induced by ROS generation. However, mechanistic evidence showing that the compounds can directly exert reductase- and foldase-like activity in living cells has not been obtained, although we provide sufficient data on the functions of the compounds from several in vitro experiments. Additionally, in vivo studies are needed to accumulate more detailed biological insights into organelles in which the compounds can localize and function prior to further validating the utility of the compounds.

In conventional catalytic chemistry, catalytic reactivity and cytotoxicity have a trade-off relationship, rendering their biological use extremely difficult41,64. The successful development of cell-driven catalysts that can up- or downregulate their bioactivity in response to a cellular environment will provide a foundation for the development of small molecular machinery that can promote a specific reaction in the desired location at the required time. Changing the type of allosteric effector and its selectivity by modifying the structure of the metal ion ligand is also expected to be possible. Furthermore, by incorporating the concept of drug delivery systems into allosteric catalysts, the molecules can potentially be used as prodrugs targeting specific tissues and organelles. We are currently seeking to develop a new class of allosteric catalysts that can be practically applied as prodrugs for the treatment of redox-related disorders, such as muscular dystrophy and neurodegenerative diseases.

Methods

All experimental details, including synthesis methods, reduction potential measurements, pKa measurements, oxidative folding assays, oxidoreductase-like activity assays, cell cultures, cellular imaging, cytotoxicity assays, and quantification of total ROS in living cells, are provided in Experimental (section 1) in the Supplementary Information.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses