Integrated fire management as an adaptation and mitigation strategy to altered fire regimes

The challenge of altered fire regimes

We are experiencing fast changes in the timing, frequency, seasonality, size, intensity and severity of wildfires worldwide1,2,3 when compared to historical ranges, i.e. altered fire regimes. Climate change modifies the fire weather3 promoting extreme fire behaviour4 and, in many regions, it has increased vegetation flammability1,3, the frequency and intensity of wildfires5 (Table 1). Overall, fire seasons lengthened by about 20% between 1979 and 20131. Model projections suggest that burned area will increase by 9–14% by 2030 and 20–33% by 2050 even under the lowest emissions scenario6. Changing climate can increase the areas where fire occurs (i.e. fire-prone areas), impacting biodiversity, disrupting ecosystem functioning and endangering health, cultures and livelihoods, all of which amplify the vulnerability of ecosystems and human populations7. Extreme fire behaviour, characterised by fast and erratic spread, abnormally high intensity, and broad fire fronts, overwhelm civil protection and fire-fighting capacities8. These new conditions pose unprecedented challenges to the economy, society 9,10 and fire governance by reducing the time window for planned fire-use11 and increasing firefighting costs12 (Table 1).

Wildfires impact the climate system by emitting large quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere: they currently account for 37.8% of the total emissions from natural sources and 16.9% of total natural and anthropogenic emissions13. Altered fire regimes are exacerbating wildfire-associated emissions. Forest fire carbon emissions have increased by 60% overall since 2001, driven largely by increased emissions from extratropical forests14. For example, wildfires in boreal forests released a record of 0.48 GtC in 2021, twice the average of the 2001-2018 period15. Fires in Canada emitted 1.3 Pg CO2 (0.39GtC) in 202316, double the total CO2 equivalent emissions for this country in 2021 (estimated to be 0.67 Pg CO2 (0.2 GtC)17). The extreme fires in Australia during the summer of 2019 emitted 0.71 Pg CO2 (0.23 GtC)18.

Altered fire regimes result from direct (e.g. ignition sources, land-use change, fire management policies19) and indirect anthropogenic actions (e.g. climate change20,21). Over the last century, human activities have profoundly modified ignition patterns and landscape flammability through land use change, fire suppression policies22 based on excluding all types of fires (even in fire-prone regions), and the disappearance of fire uses and practices linked to traditional ecological knowledge23. These changes, combined with extreme wildfire activity in recent years, have revealed the limitations of prevalent fire policies focused on emergency response and fire-suppression, underscoring the need for more integrated, effective, and holistic fire management strategies.

Integrated fire management (IFM) – an holistic approach that integrates management, ecology and society – may help address the consequences of past fire suppression policies and challenges posed by altered fire regimes by applying a nuanced understanding of fire’s ecological and cultural dimensions. However, its applicability though has not yet been systematically assessed.

This review examines current fire management practices, with a focus on IFM as an adaptation and mitigation strategy to altered fire regimes. We review the concept of IFM, assess the progress and challenges in its implementation across different regions worldwide. We then propose five core objectives and a roadmap of incremental steps for implementing IFM as a strategy to adapt to ongoing and future changes in fire regimes, and maximise the potential of IFM to provide benefits to people and nature.

Shifting paradigms: from fire suppression to integrated fire management

Over the past few centuries, most fire management strategies have predominantly focused on emergency responses and fire suppression, and on fire bans as the only way of wildfire prevention. Active, organised fire-fighting emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries in Europe, Australia, and the North America, and spread to other parts of the world aided by colonial influence24. This fire suppression approach (reinforced since the 1970’s with aircraft water firefighting) did not recognize the ecological role of fire or its local cultural and social significance24,25, and failed to understand that numerous local forms of fire use were acts of fire prevention or reduction of fuel build-up26. Socio-economic and land-use changes in the 20th century—such as rural abandonment (i.e., migration from rural to urban areas) in Europe, the growth of industrial forestry and agribusiness in South America, and the expansion of residential areas that increase the wildland-urban interface in North America and Europe — have strengthened the perception of fire as a universal threat to society and ecosystems. This has led to a widespread perception that fire should be suppressed at all costs, regardless of the type of fire. This misleading belief that fire is a controllable artefact, rather than a natural process intrinsic to ecosystem dynamics, has been enhanced by media misinformation27 and biased debates28,29.

Legislation criminalising traditional and Indigenous fire practices29,30, coupled with large investments in suppression technologies, have bolstered anti-fire perceptions worldwide, even where fire removal has had negative impacts on ecosystems or local livelihoods that are embedded in traditional fire management practices, exacerbating social disadvantages and inequality. Fire suppression policies have been predominantly aimed at reducing burned areas without addressing fire prevention or post-fire recovery, leaving a legacy of homogeneous landscapes with high fuel loads that enhance the risk of large and catastrophic wildfires26,31,32.

The fire management community’s acknowledgement of the long-term ineffectiveness of suppression-centric policies in preventing destructive fires has led to the development of prevention-oriented programs33,34. Some of these include active ecosystem management (e.g. prescribed burning programs) to minimise wildfire risk35. Other approaches (e.g. holistic fire management’36, ‘Indigenous fire stewardship’37, ‘intercultural fire management’25, ‘cohesive management’38 and ‘community-based fire management’39,40) aim at revitalising local and Indigenous knowledge as a mechanism for fire management, territorial care, and place making.

The concept of IFM, initially coined in the 1970s41,42, marked a shift towards a more comprehensive strategy that emphasised fire prevention and preparedness, and promoted ecological recovery after fire, moving beyond emergency responses to fire. Myers et al.43 defined IFM as an approach that integrates three fundamental dimensions of fire: management (encompassing prevention, suppression and fire use), ecology (focusing on key ecological attributes of fire) and culture (considering both the socio-economic and cultural imperatives for fire use along with the negative impacts that fire can have on society). The concept of IFM defined by Myers et al.43 has gradually gained recognition among fire practitioners and scientists because of its potential to deliver effective, efficient and equitable fire management. IFM builds on synergies between multiple goals such as wildfire risk mitigation, biodiversity conservation and restoration, landscape resilience, improving livelihoods and preserving knowledge and cultural values44.

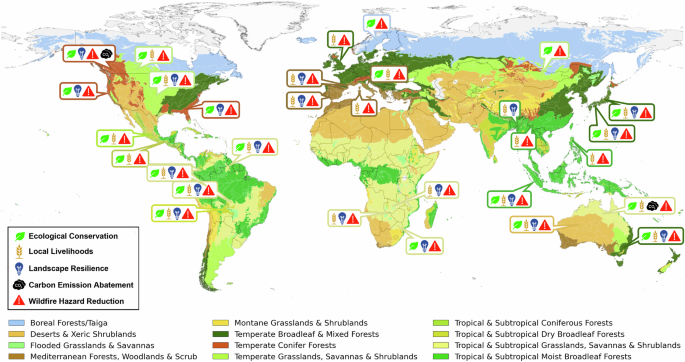

IFM is context-dependent and therefore must be planned in accordance with the local socio-ecological specificities and management objectives (Fig. 1). The achievement of IFM objectives requires an understanding of the ecology of the system (including fire-sensitive ecosystems), the services the ecosystems provide, and how these properties are affected by fire types, from the perspective of multiple actors and sectors. However, despite the attention it has gained and the many IFM initiatives that have flourished around the world, the lack of a formal definition, standardization and regulation – which is the result to a lack of political will – has kept IFM initiatives at relatively small scales. This is a missed opportunity, especially in face of the climate changes that are changing the flammability of many landscapes and, together with other anthropogenic drivers, profoundly altering fire regimes worldwide. IFM can not only help people to re(learn) to live with fire, and with wildfires, it can also revitalise traditional and Indigenous knowledge, maintain ecosystems services and assist in adaptation and mitigation policies to the emergent new fire regimes.

Some geographical locations may contain several initiatives. See Supplementary Table S1 for a complete list.

Advances in developing and implementing IFM

Countries are at varying stages in the adoption and implementation of IFM: some countries have made rapid advances by providing adequate frameworks and establishing IFM programs, others are still in the early stages of adoption (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). Despite challenges in implementing and achieving conservation and management goals, most of these initiatives represent a step-change towards reducing wildfire risk, and promoting ecological and social integration, and cultural acknowledgement (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). As an example, Australia has pioneered carbon mitigation efforts based on Aboriginal fire-use practices, predominantly administered and managed by Aboriginal communities living in the region45. The pioneer Western Arnhem Land Fire Abatement (WALFA) project in northern Australia, a partnership involving Aboriginal peoples and the industry sector, focuses on savanna-burning for the carbon market46. During its initial years, WALFA decreased mean annual emissions by 38% relative to the baseline47. In California, prescribed burning on Yurok and Karuk tribal lands is part of their forest carbon-offsets selling scheme48.

Fire management in several African nations is still largely influenced by colonial legacies, characterised by top-down centralised governance, suppression-centred policies, and under-resourced approaches49. Consequently, despite the prevalent and culturally significant practice of community-based fire use as a land management tool across many African communities (e.g. refs. 49,50), there is often a lack of adequate institutional support for effective use of resources for IFM that would bring both ecological and societal benefits including contributing to climate change adaptation. However, where resources are available, IFM can achieve several goals and balance needs. For example, in Kafue National Park (Zambia), IFM supports a sustainable fire regime that fosters ecotourism with open-space maintenance, providing job opportunities, and allowing farmers to use fire for pasture maintenance, pest control, crop residue disposal, and maintain high-yield crops (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1)51.

In Ethiopia, efforts are underway to develop a national IFM strategy that acknowledges traditional uses of fire and develops a national system aimed at reducing wildfire risk, including an early warning system. An important step forward was made in 2023 with the acknowledgement that fire suppression enforcement was inadequate and ineffective, and the identification of priorities, key actors and steps needed to develop an effective national IFM strategy52,53.

There are several initiatives implementing IFM in Latin America. In Brazil, IFM was progressively introduced in Indigenous Territories (ITs) and Conservation Units since 2013 through initiatives including the establishment and training of Indigenous fire brigades, the integration of traditional Indigenous fire-use practices into official fire management plans, the development of a governance structure established through signed agreements between Indigenous Communities and federal agencies, and the advancement of research and monitoring through scientific programs54 (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). In July 2024, Brazil was the first Latin-American country to approve a Federal Law on Integrated Fire Management55. In the Brazilian regions where IFM is used, it has successfully reduced the annual burned area affected by wildfires by almost 20%54. In Mexico, IFM principles and actions have been progressively implemented in several places since the early 2000s56 and the country incorporated IFM in the new national Law on Sustainable Forest Development (approved in 2018 and enacted in 202157). Currently Mexico has a nation-wide fire management plan that recognizes the ecological and social role of fires, and establishes actors and responsibilities for different aspects of the plan58. In the Amazonian basin, OTCA (Organización del Tratado de Cooperación Amazónica) is an example of a supra-national governance organisation that in 2021 promoted a Memorandum of Understanding on Integrated Fire Management59 that has been signed by the OTCA member countries (Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Perú, Surinam, Venezuela). This agreement has been a precedent for several national initiatives promoting IFM. In Bolivia, indigenous and traditional communities in the Chiquitania region have been part of a community-based fire initiative that has promoted and implemented IFM practices since 201140. Similarly, Venezuela’s INPARQUES Fire Brigade has embraced IFM with intercultural practices since 2015, building on the integration of Indigenous and scientific knowledge with the technical expertise of its forest firefighting teams60.

In Southeast Asia, more integrated approaches to the classical fire management of peatland fires have been under consideration. When wildfires are powered by the combustion of deep layers of drained peat, the classical fire suppression strategies are insufficient to control and extinguish fires. In the Indonesian regions of Riau, Sumatra (Jambi and Palembang) and Central Kalimantan, multiple bottom-up initiatives have emerged in reaction to this situation by moving from the existing fire suppression model towards community-based fire prevention, preparedness, and suppression strategies61,62. These strategies have a positive impact in reversing land abandonment caused by the sale of land to external investors with exploitation interests63 and support a transition towards sustainable livelihoods, where fire is used as a cost-effective method for localised clearing of land for agriculture and fishing. However, despite the interests of local communities in IFM, their engagement remains limited due to a lack of institutional and financial support61.

In Europe, fire management programs using prescribed burning have been implemented since the 1980s by professional organisations and networks. Examples of fire management programs evolving into more holistic IFM practices are found in Portugal, France, Spain, Italy, and Sweden64,65. For example, a prescribed burning program was initiated in the Pyrénées-Orientales region (southern France) in the 1980s to manage shrub encroachment and restore natural grasslands for pastoral purposes66. This program has evolved towards serving multiple objectives: open spaces for pastoralist uses, biodiversity conservation of key flora and fauna species, management of game fauna, fire-managers training, and wildfire risk reduction (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). The governance structure includes national and regional agencies as well as the local communities who are partly responsible for prioritising areas to burn and for executing the prescribed burns66.

The grass is not always greener: current constraints on IFM

Fire management is a ‘wicked’ problem67 encompassing many social, ecological, economic and governance layers, for which there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution. This complexity has slowed the shift from emergency-focused fire management policies. Strong fire risk aversion perceptions and a lack of regulatory frameworks have hindered the development and implementation of IFM at large scales. IFM is inherently a multi-faceted approach, but the terminology ‘Integrated fire management’ has often been applied to management strategies limited to prescribed burns for wildfire risk reduction, without fully accounting the social or ecological perspectives.

The perception that IFM initiatives necessarily involve the use of controlled or planned fire have also given rise to criticism about the impacts of these fires on air and water quality68. Whenever fire is used, a careful consideration of the risks to human health and air quality is needed. Furthermore, the ecological impacts of planned burns must also be considered, especially when fire is not a natural component of the ecosystem, or when planned burns do not have ecological objectives and are carried out at a different time from the natural burning season in that ecosystem. For example, planned burns for wildfire risk reduction or carbon abatement potential can severely impact the phenology and life history of communities69. The introduction of early season burning in African savannas aimed at reducing wildfire risk and greenhouse emissions70, highlights the need for caution. African savannas include many different vegetation types from open ecosystems with perennial grasses to ecosystems dominated by shrubs and deciduous woody vegetation. Vegetation dominated by woody plants is often too moist to burn in the early dry season, causing lower combustion rates and higher emissions. Many African ecosystems have experienced significant woody encroachment over the last few decades71,72, and early-season burns will thus be less effective in reducing fuel loads.

Progress in establishing regulatory frameworks that fully embrace IFM and its socio-ecological importance has been slow in most places of the world. For example, in Bolivia, Colombia, and Venezuela bills to implement new national IFM policies have been proposed but await formal approval. There are no policies or standardised IFM programs in any European country, and fire management activities in many countries (e.g. Portugal, Spain, France) tend to aim exclusively at reducing wildfire risk73. This is also the case for the many countries in the African and Asian continents. In Europe, an added challenge is the lack of detailed knowledge about traditional/cultural burning (but see refs. 74,75,76,77), how it was practiced and to what extent it is still being used. Fire-exclusion policies and land abandonment have led to increased fuel accumulation across Europe, creating fundamental social and economic changes that are a challenge to developing IFM programmes78.

Setting IFM as an adaptation and mitigation strategy to altered fire regimes

IFM – by holistically integrating environmental, sociocultural, economic and management perspectives – could be a powerful strategy to mitigate and adapt to changing fire regimes. However, to date, IFM programmes are still context specific. The recently updated IFM Voluntary Guidelines from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)79 provide a good basis of what needs to be considered when developing an IFM program, but these guidelines are rather broad. Here, we advance by proposing five core interconnected objectives that IFM programmes should adopt to adapt their territories, peoples and nature successfully to new fire regimes and mitigate the impacts of destructive wildfires:

Enhance landscape resilience

Resilient landscapes can maintain, renew and strengthen their fundamental qualities despite disturbances or ongoing changes80. Climate change impacts fundamental qualities such as water and food security, or wildfire risk. IFM can mitigate these through the integration of climate projections into fire risk prediction, the development and implementation of holistic land management practices that include fuel treatments, and through community engagement and coordinated collaboration among fire prevention and emergency response agencies81,82. This can assist adaptation through bottom-up approaches that incorporate traditional knowledge, education, and understanding of the local socio-ecological and economic contexts to design and implement integrated landscape planning strategies through preparedness, response and recovery actions. Such an approach should make use of a combination of early warning systems, community engagement, land use and urban planning, sustainable schemes for fuel management, emergency response planning, research, and collaboration among various stakeholders81,83. Lastly, any IFM actions need adequate metrics to measure effectiveness in a given landscape and facilitate adaptations to changing conditions.

Promotion of local livelihoods and knowledge

Combining knowledge and understanding and applying traditional fire-use practices not only enhances ecosystem resilience, mitigates fire severity, and protects biodiversity but also aligns modern conservation efforts with centuries of ecological and cultural practice. Local knowledge holders, who witness current climate change impacts alongside historical fire and landscape uses, are deeply tied to the environment84,85. It is estimated that Indigenous Peoples steward or hold tenure rights over at least 37% of the Earth’s natural lands, containing more than one-third of the world’s intact forests86.

Traditional knowledge can promote ‘cool’ low-intensity fires that prevent ‘hot’ uncontrolled wildfires and facilitate adaptation to new fire regimes in ecosystems that do not cope with high intensity fires. It can also enhance ecosystem resilience via agro-silvo-pastoral activities, and facilitate post-fire restoration by selecting appropriate species and sites, and invasive species control. Integrating local knowledge with modern scientific and management methodologies improves ecological outcomes, reduces economic costs, and fosters social acceptance87,88,89. In some systems, the use of low-intensity fire can enrich the soil with nutrients, while rotational burning practices can ensure that ecosystem functions have sufficient time to recover, both crucial for sustaining small-scale subsistence agriculture and food security90,91. Planned fires can mitigate wildfire severity, safeguarding crucial resources such as forests and grazing lands essential for local communities’ needs, including livestock forage, medicinal plants, and timber. Fire management can also create economic opportunities by increasing food production for local trade, attracting ecotourism through biodiversity conservation activities, and enabling sustainable harvesting of non-timber forest products.

The role that local communities play in preserving biodiversity and regulating fire within safe boundaries should be rewarded, for instance, by accounting for avoided damages to other ecosystem services and acknowledging how this contributes to climate change adaptation92.

Ecological conservation and restoration

In response to the increasing biodiversity crisis93, the United Nations has declared 2020-2030 as the Decade of Ecosystem Restoration. This requires consideration of options for restoring biodiversity and ecosystem function. IFM initiatives can be part of these options because they support climate change adaptation by moderating extreme fires and buffering their impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity94.

Ecosystems are inherently complex systems and IFM has to account for site-specific conditions to achieve ecological goals, including identification of key species and the adaptability of different species to fire. Planned burning (e.g. patch mosaic burning), for example, creates mosaics of different habitats and promote species diversity and natural ecosystem regeneration after fires95,96. IFM can also promote natural regeneration by preserving potential refugia and conserving mature ecosystems that are essential to maximise biodiversity and resilience97,98. Preserving riparian corridors, for example, provides natural pathways for species dispersal99 and may provide refuges during droughts or wildfires100.

IFM aimed at reducing fuel loads and continuity can help maintain biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in open habitats. In Southern Europe, for example, land abandonment has negatively affected open habitat species, such as wet grassland or early successional species. IFM can help restore these ecosystems while promoting greater fire resistance and climate-adaptive landscapes77.

Mitigation of wildfire risk

IFM can mitigate wildfire risk through fuel management strategies targeted at changing vegetation composition and structure, reducing fuel load, or reducing vegetation continuity44. The choice of strategy depends on the local context and management goals. Fuel treatments to reduce the accumulation of surface fuel (litter, grasses, shrubs) include planned fire-use (from fire-use by communities to prescribed burning), the mechanical or manual clearing of understorey vegetation, and grazing. Silvicultural practices — pruning and thinning, variable retention harvesting, closer-to-nature forestry — may be designed to either decrease the likelihood and intensity of a crown fire or decrease understorey flammability through increased shading and sheltering.

Linear fuel breaks are designed to limit the spread of wildfires, but their effectiveness is highly variable101. Traditional pastoral and aboriginal burning in Europe102 and Australia103 respectively, has been shown to decrease wildfire size substantially. Similarly, area-wide fuel treatments (either prescribed burning, thinning, or both) have been shown to mitigate wildfire extent and severity104,105,106. Although extreme fire weather may override the effects of fuel treatments on wildfire spread, environmental and societal benefits will persist as long as heat release, which correlates with fuel load, remains lower than in untreated areas107. Lastly, fuel treatments may have some harmful ecological consequences (e.g. landscape fragmentation) that could be avoided or mitigated if fuel treatments were designed and maintained in a way that are not detrimental to other objectives.

Carbon emission abatement

Increased or stabilized carbon storage may arise as a by-product of forest fuel-reduction treatments, depending on the amount and frequency of carbon removal and the effects on future wildfire probability and severity108. Mitigation of carbon emissions can be an explicit or even primary fire management goal if it also brings socio-ecological benefits. In many fire-prone areas, changing fire regimes – such as later-season burning – have led to higher fire intensity70. Such areas can be managed, depending on the local ecological context, by early to mid-season burning that is less intense, emits less greenhouse gases and decreases the risk of extreme and large wildfires in the late dry season47,70.

Thus, carbon emission abatement resulting from IFM can open a window of opportunity for compliance and voluntary carbon market schemes that can benefit local communities by enhancing social resilience, however this is context dependent. While this is a potential added opportunity, it is not a panacea: application in Australia remains limited to a few vegetation types47, and is hindered in Eastern and Southern Africa by multiple challenges associated to asymmetries of the IFM goals (e.g. biodiversity restoration versus carbon emission abatement39,109,110) as well as between local governance systems and formal institutions111. Carbon abatement programmes should be assessed according to a country position statement, which prioritises climate change adaptation and mitigation alongside biodiversity conservation and the local communities involved in such initiatives.

Roadmap for countries

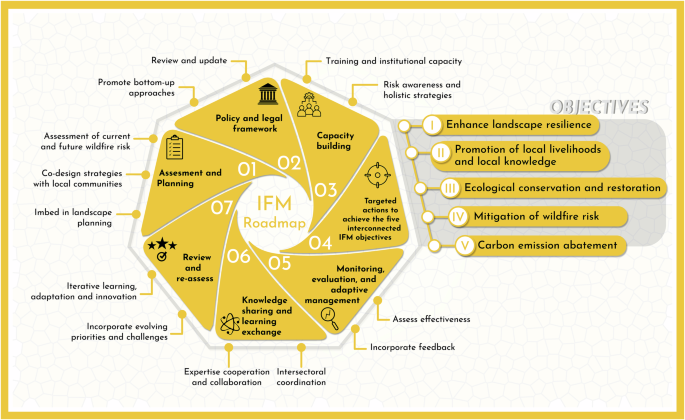

Building on the insights synthesized in this review, we propose a roadmap to implement Integrated Fire Management (IFM) at national or regional scales. This framework integrates the five core objectives described above, addresses diverse fire scenarios, engages multiple stakeholders, and considers potential risks to ensure informed and adaptive decision-making (Fig. 2).

-

1.

Assessment and planning phase:

-

Conduct a comprehensive assessment of current and future wildfire risk and vulnerability to extreme events, considering both ecological and socio-economic factors112.

-

Establish the desired level of fire to maximise biodiversity and ecosystem function, while allowing the use of fire for pastoral, agricultural and cultural purposes.

-

Co-design IFM strategies with clear short-, mid- and long-term objectives, targets, and actions, and identifying potential pitfalls and undesired side effects (e.g. increased CH4 emissions from grazing, ecological damage linked to planned burning outside the fire season or where fire is not a natural agent).

-

Embed IFM strategies as part of wider landscape and territorial planning81, enhancing rural communities’ cultures, values and livelihoods that contribute to the preservation of fire knowledge, wildfire risk reduction and biodiversity conservation.

-

2.

Develop a policy and legal framework

-

Review and update existing policies and legal frameworks to integrate IFM principles and practices ensuring that bottom-up practices (e.g. traditional fire use) are covered and supported by the legal framework.

-

Establish regulations and incentives to promote IFM adoption and incentivize sustainable fire management practices, minimising risk-aversion to fuel treatments.

-

Ensure that emergency response policies encompass IFM. Decision-making during large incidents must take into account different levels of governance, knowledge and community-based fire management.

-

3.

Capacity building:

-

Invest in capacity building for IFM implementation, including training programs for fire practitioners, land managers, policymakers and members of the local community.

-

Train emergency responders, in particular decision-makers, in fire analysis/assessment, fire ecology and fire use, so that they have a better understanding of the impacts their decisions on local socio-ecological dynamics.

-

Raise awareness of emerging challenges and propose holistic adaptation and mitigation strategies that combine local knowledge with scientific and technical understanding113.

-

4.

Address risks of undesired effects and implement actions to achieve the five interconnected IFM objectives (Table 1):

-

Implement landscape-scale approaches to enhance landscape resilience to wildfire and climate change impacts. This may include ecosystem-based adaptation measures such as natural buffer zones and green infrastructure.

-

Promote local livelihoods and local knowledge by supporting the revitalization of Indigenous and traditional fire management practices. This should involve incorporating traditional ecological knowledge into IFM strategies and developing sustainable livelihood opportunities, such as eco-tourism114, agro-silvo-pastoralism83, and sustainable forestry115.

-

Prioritise the conservation of key species within the landscape acknowledging their socio-ecological role. This involves identifying and prioritising biodiversity hotspots, biota refuges and critical ecosystems and implementing sensible habitat restoration programs and promoting ecosystem resilience while minimising damage to co-existing fire-sensitive species.

-

Implement fire prevention strategies, including planned fuel treatments to decrease flammability by changing vegetation structure and/or changing vegetation composition. It is important to use ecologically sound strategies and minimise edge effects in fire-sensitive ecosystems116.

-

Co-develop projects for carbon sequestration through sustainable forest management and carbon trading mechanisms, but considering ecological criteria and social justice and principles of equitable sharing of benefits117.

-

5.

Monitoring, evaluation, and adaptive management:

-

Establish monitoring and evaluation frameworks to assess the effectiveness and impacts of IFM actions incorporating feedback mechanisms to adapt strategies based on new insights, such as the unforeseen impacts of early season burning on gas and particulate matter emissions118.

-

Use adaptive management principles to adjust strategies and actions based on new information, changing conditions, and stakeholder feedback.

-

6.

Knowledge sharing and learning exchange:

-

Facilitate knowledge sharing and learning exchange among regions and countries to promote best practices in IFM implementation. It is important to ensure the traceability and due recognition of the local and regional knowledge by providing appropriate means and channels for knowledge transfer.

-

Enhance local cooperation and knowledge sharing across government agencies, communities, Indigenous Peoples, non-governmental organisations, and other relevant stakeholders.

-

Foster collaboration with international organisations, research institutions, and relevant networks to access technical expertise and support capacity building efforts ensuring that emerging challenges like unexpected air quality issues from prescribed burns are addressed.

-

7.

Review and re-assess:

-

Review and update the IFM strategy and action plan periodically based on evolving priorities, lessons learned, and emerging challenges.

-

Improve IFM implementation continuously through interactive learning, adaptation, and innovation emphasising the importance of transparency about the potential negative impacts to foster a robust, adaptable management strategy.

This roadmaps involves seven core steps (see section ‘Roadmap for Countries’) and five main objectives (see section ‘Setting IFM as an adaptation and mitigation strategy to altered fire regimes’ for a description).

Incremental application of the proposed Roadmap

Transitioning from fire suppression systems to IFM systems at national level, as outlined in the proposed Roadmap (Fig. 2) requires significant policy reforms, and the adoption of new strategies at institutional, governance and social levels. Countries like Brazil and Mexico are successfully implementing IFM by shifting policy, delineating governance frameworks and promoting multi-stakeholder collaborations. However, because of its complexity, the implementation of the Roadmap has to be made through incremental steps to ensure feasibility and allow the flexibility required to adapt to local and regional contexts.

This incremental process takes existing local IFM practices as a baseline (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). Local or regional centres of IFM practices have a fundamental role in setting the knowledge-science basis and producing scalable and realistic expertise for the implementation of the Roadmap. Local examples contribute to demonstrating the success of implementing IFM practices in local and regional socio-ecological systems and landscapes and generate opportunities for replication. They also provide a proof of concept for the effectiveness of IFM practices, and contribute to building a robust scientific understanding of IFM for implementation at a wider scale and in other contexts. Further development of IFM practices should involve establishing hubs for exchanging knowledge, learning together, building capacity and testing new context-specific approaches and involving members of the local population to raise awareness and trigger changes in societal perception about fire uses81,90.

The path to escalate from local implementation of IFM practices to a widespread approach relies on implementation of steps 1–7 of the Roadmap (Fig. 2). To achieve this, countries must leverage their local and regional expertise and experience, and complement this with experiences and scientific insights from other regions and internationally. This can be supported through the enhancement of knowledge networks.

Although updating the legal frameworks is a fundamental step to formalise the IFM implementation, the multiple bottom-up actions discussed here contribute to advance the implementation of IFM under the current policy frameworks and without requiring specific IFM policies. However, effective governance structures and process facilitators are essential for coordinating actions and collaborations across multiple levels. The widespread implementation of IFM at regional and national scales depends critically on step 2 of the Roadmap ‘Develop a policy and legal framework’35. The practitioner community implementing IFM practices on the ground must have that legal support to ensure the sustainability of the local IFM practices over time, to upscale local knowledge and to develop region or country-wide policies and strategies. Countries need to ensure that there are appropriate national and supra-national structures to ensure funding and infrastructure are available.

Overcoming challenges for implementing IFM: future lines of research

The success of IFM relies on establishing a dialogue between traditional knowledge, land managers, fire science and fire policy through a strong collaboration between actors from different sectors and disciplines supported by boundary-spanning organisations. This dialogue is necessary to address simultaneously the ecological, economic, and social aspects of fires while recognizing the complexities of integrating actions across spatial and temporal scales and different governance systems (Table 1).

Legal and normative frameworks must recognize the socio-ecological role of fire and enable adaptive management policies. These frameworks should aid allocating economic resources toward building resilient landscapes through prevention, adaptation, and mitigation actions. Along with engaging local communities, adequate legal frameworks and economic resources can support adaptive vulnerability assessments and translate these into effective strategies for building capacity in local populations. Effectiveness studies are needed to ensure policies remain flexible and responsive to evolving conditions and knowledge bases.

Clear metrics and objectives are important for measuring the success and impact of IFM approaches. IFM effectiveness also relies heavily on ongoing research and adaptation to changing conditions, which requires significant efforts for which resources need to be allocated (Table 1). A forward-looking approach is essential, with priorities and future directions emphasising the development of dynamic, data-driven models for fire risk assessment. These models should leverage real-time environmental data and predictive analytics (scenarios), complemented by local capacity building to identify new fire-prone areas, including those where extreme fire behaviour is likely. Enhancing the ability of fire behaviour models to describe and predict extreme phenomena is also necessary. Planning for post-fire recovery, understanding the ecology of areas that are becoming fire-prone, and integrating research that combines fire likelihood with hydrology and erosion models require more ground data and investment in long-term research programs (Table 1).

While IFM often uses controlled, low-intensity burns to manage vegetation and reduce wildfire risk, the increasing risk of high-intensity burns – including both uncontrolled wildfires and “escaped” prescribed or planned burns – poses significant challenges. These intense fires can destroy soil seed banks, deplete essential nutrients, and alter soil structure, which inhibits natural regeneration and increases erosion risks. Additionally, they generate higher levels of greenhouse gas emissions and particulate matter, impacting air quality and contributing to climate change. Recent studies link the rising frequency and intensity of these fires to climate change, with cascading effects on biodiversity and ecosystem function119. To address when and where fire is an appropriate tool, IFM practices must prioritize carefully timed, low-intensity burns and incorporate adaptive management strategies that account for evolving climate conditions and the growing challenges of conducting safe, planned burns.

IFM approaches should also include justice aspects, especially when dealing with climate financing markets such as carbon abatements. Conflicting objectives, such as the negative impacts on biodiversity of early season burning plans needed to meet carbon abatement goals and reduce wildfire risk, need to be addressed through multi-stakeholder knowledge sharing and cooperation. Fostering multi-actor cooperation and collaboration, alongside legal frameworks that support adaptive management policies will be crucial. Effective stakeholder collaboration and knowledge sharing, community-based capacity building and empowerment, and the integration of IFM into broader climate change policies are imperative to overcome the current challenges to the implementation of IFM.

Conclusions

IFM incorporates ecological and socio-cultural dimensions into the management needs for wildfire prevention, response and recovery. As such, it can be an effective tool to manage and restore fire-prone ecosystems because it simultaneously addresses societal challenges with the use of an ecological process that has multiple benefits for landscapes, society and nature.

IFM adopts interconnected objectives that directly address the impacts of climate change on fire regimes, fire behaviour, landscape resilience, biodiversity, and social systems. By reducing the risk of uncontrolled wildfires, IFM helps protect carbon stocks, conserve biodiversity, and safeguard community assets while building ecosystem resilience to future changes in fire regimes and climate. This dual role positions IFM as an invaluable strategy within climate policy frameworks, especially in regions experiencing increasing fire frequency and intensity.

The alignment of IFM with climate resilience and sustainable development goals highlights its potential to be integrated into policy frameworks at both national and international levels. As countries seek scalable, multi-benefit strategies to manage climate risks, incorporating IFM into adaptation and mitigation policies offers a proactive path to protect ecosystems and communities alike.

This review proposes a roadmap for effective IFM implementation, highlighted some of the current challenges and identified priorities and future research directions. This roadmap is designed to help nations address immediate wildfire risks and contribute to efforts to adapt to new fire regimes, but will also promote climate change adaptation and provide mitigation benefits. Future progress towards broader adoption of IFM programs requires the acknowledgement of the need to build resilient landscapes and a resilient society that allows us to live with altered fire regimes.

Responses