Effects of input modality and second-language vocabulary proficiency on processing of Japanese compound verbs

Introduction

Formed from two or more root words, compound words exemplify lexical diversity and complexity, making them crucial in studying the lexical richness of second-language (L2) learners (Fiorentino and Poeppel 2007; Zhang and Chen 2012; Libben et al. 2020). Previous studies on compound word processing have mainly focused on phonographic languages (e.g., Libben et al. 2003; Schmidtke et al. 2021; Creemers and Embick 2022), with almost no research addressing ideographic writing systems, such as Japanese compound verbs (Yao 2022). Known for their complex structures and numerous varieties, the morphemes and the whole word among Japanese compound verbs are often not perfectly aligned semantically (Zhang and Liu 2018). Meanwhile, the sharing of lexical representations of Chinese character words in Chinese–Japanese bilinguals’ mental lexicon makes them susceptible to the orthographic and semantic differences between Chinese and Japanese (Chen 2022). These unique linguistic features have led to widespread attention being paid to Japanese compound verbs in linguistics, L2 acquisition, and psychology (Japan National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics 2015).

However, there has been relatively limited comprehensive discussion of factors influencing the processing of L2 Japanese compound verbs. Therefore, this study employed psychological experimental methods to explore the impacts of input modality, i.e., whether the words are presented visually or auditorily, and L2 vocabulary proficiency on the processing of different types of Japanese compound verbs, aiming to provide empirical evidence for L2 vocabulary teaching and acquisition.

Literature review

Classification and semantic transparency of Japanese compound verbs

In Indo-European languages, the classification of compound words often depends on semantic transparency, focusing on the relationship between the meanings of the constituent morphemes and the whole word (e.g., Libben et al. 2003; Libben, 2014; Li and Ni 2023). Compared to the classification of compound words in Indo-European languages, the classification of Japanese compound verbs is relatively complex and lacks uniform standards. Among the proposed standards, Teramura (1984) introduced criteria based on the semantic independence of the first verb (V1) and the second verb (V2), and Kageyama (1993) based his classification on lexical integrity. These widely applied standards have advanced the study of Japanese compound verbs, although issues of overlapping categories and unclassifiable verbs remain unresolved (Zhang and Liu 2018).

To standardize the teaching and research of compound verbs, the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics in Japan has created a modern Japanese Compound Verb LexiconFootnote 1 that categorizes compound verbs into four types based on the grammatical and semantic characteristics of the constituent morphemes, following the criteria established by Kageyama (2013). In the first type, i.e., VV, there are strong semantic relations with the whole verb and the original case relations are maintained; an example is 持ち歩く (mochi-aruku, “carry and walk”), where both V1 (carry) and V2 (walk) are strongly related to the overall semantics. In the second type, i.e., Vs, only V1 has a strong semantic relation and maintains the original case relation; an example is追い掛ける (oi-kakeru, “chase”), where V2 (hang) has lost its original meaning and grammatical function and now merely supports V1 (chase). In the third type, i.e., pV, only V2 has a strong semantic connection and maintains the original grammatical relationship; an example is食い止める (kui-tomeru, “stop”), where V1 (eat) has lost its original meaning and grammatical function and now merely supports V2 (stop). In the fourth type, i.e., V, both V1 and V2 have weak semantic connections with the whole verb, which is often considered as a single word based on usage habits and linguistic feel; an example is落ち着く (ochi-tsuku, “calm down”), where both V1 (fall) and V2 (reach) have lost their original meanings.

While the classification standards of Japanese compound verbs and semantic transparency seem consistent, aligning them perfectly is challenging. First, the standard of semantic transparency is often applied to nouns, whereas Japanese compound verbs, which have stronger grammatical functions than nouns and strict morphological constraints (Uchiyama et al. 2005), cannot be classified solely based on semantic connectivity. Also, Japanese verbs often have multiple meanings, making the semantics of compound verbs formed from two verbs even more complex; classification based solely on the semantic characteristics of the constituent morphemes may lead to significant deviations. Moreover, the orthographic representation of Japanese verbs in Kanji can influence Chinese learners’ processing of whole-word semantics because of transfer from their native language. Therefore, studies on Japanese compound verbs must consider grammatical aspects, semantic transparency, and native-language transfer to maximize accuracy of the research results.

Factors that influence the processing of compound words

The complex semantic features of compound words and their accessibility mechanisms have attracted significant attention (e.g., Libben et al. 2003; Schmidtke et al. 2021; Creemers and Embick 2022). Research into the representational models of compound words, independent of their constituent morphemes, has proposed three processing models. The decompositional model posits that the representation of compound words is achieved through morphemes, with semantic processing completed based on morphological decomposition (e.g., McCormick et al. 2008; Brooks and Cid 2015). The full-listing model suggests that compound words exist independently in the brain like simple words, with semantic processing completed without the need for morphological decomposition (e.g., Seidenberg and Gonnerman 2000). The dual-route processing model asserts that compound words have representations of both whole words and morphemes in the mental lexicon, with both holistic and decomposed processing occurring simultaneously (e.g., Macgregor and Shtyrov 2013).

There is no consensus on the processing models of compound words, and research is focused on the effects of factors such as frequency, familiarity, and semantic transparency. Most studies suggest that holistic processing models are more prevalent for high-frequency or familiar compound words, while decomposed processing models are more common for low-frequency or unfamiliar ones (e.g., Marelli and Luzzati 2012).

In contrast, the impact of semantic transparency on compound word processing varies. For instance, studies involving native speakers show that semantic transparency has a weak effect on compound word processing. Visual cue-based processing of German compound nouns (Smolka and Libben 2017), Japanese compound verb processing (Yao 2022), and auditory cue-based processing of English compound nouns (Creemers and Embick 2022) all indicate a decomposed processing model, with semantic transparency having no significant impact on compound word processing. Conversely, studies involving L2 learners show that semantic transparency significantly affects compound word processing. Shabani-Jadidi (2016) explored the impact of semantic transparency on the processing of compound verbs in Persian learners using a masked priming paradigm; the study found activation effects when both transparent and opaque words were presented, with a larger activation effect when transparent words were presented, supporting the dual-route processing model.

Chen et al. (2020) used a lexical decision task to investigate the effects of semantic transparency and familiarity on English learners’ processing of compound nouns; the results indicated that the impact of semantic transparency is contingent on familiarity, with high-familiarity compound nouns tending toward holistic processing, supporting the dual-route processing model. Wang et al. (2010) used a lexical decision task to explore the effects of semantic transparency, translational congruency with native Chinese, and L2 proficiency on English learners’ processing of compound nouns; the results showed that the impact of semantic transparency is moderated by congruency and L2 proficiency, with high-proficiency learners tending toward holistic processing of opaque and differently translated words. These results highlight the need to consider multiple factors such as linguistic attributes and learner characteristics when studying the processing mechanisms of L2 compound words.

Furthermore, in their analysis of compound word processing mechanisms, Libben et al. (2003) introduced the concept of the headedness effect, suggesting that participants tend to focus on processing the second morpheme in English. Specifically, compounds with a transparent second morpheme (OT/TT) yield faster response times compared to those with an opaque second morpheme (TO/OO), while no significant differences in response times are observed among compounds with the same type of second morpheme. This headedness effect has been confirmed in other studies (e.g., Libben and Weber 2014; Creemers and Embick 2022) and is considered an important reference point for distinguishing between decomposed and holistic processing models (Li and Ni 2023). In contrast, the headedness of compound verbs in Japanese remains less clear, particularly in the context of processing by L2 learners.

For Chinese–Japanese bilinguals, visual processing benefits from the orthographic similarities between Chinese and Japanese, which facilitate recognition through shared character features. In contrast, auditory processing encounters challenges due to the phonological differences between the two languages. These challenges are particularly evident when there is a high degree of phonological similarity, as this can introduce interference during processing, leading to longer response times. This suggests that while shared features in the visual modality support faster recognition, the auditory modality is more susceptible to cross-linguistic interference, underscoring a critical divergence in how Chinese learners process Japanese vocabulary through different input modalities (Fei et al. 2022; Song et al. 2023). Based on this, it can be inferred that in addition to the language features of compound verbs inducing the headedness effect, input modality may also trigger this effect. These discussion points also reflect the research value of Japanese compound verb processing mechanisms in the fields of linguistics, L2 acquisition, and psychology.

Objectives of this study

There are two key discussion points in research studies on compound word processing, the first being the issue of research breadth. Studies of L2 compound word processing have been focused primarily on English, thereby lacking empirical evidence from other languages (e.g., Gao et al. 2022). Moreover, previous research has been focused mainly on compound nouns, while compound verbs, which have stronger grammatical functions and more complex processing models than compound nouns, have received less attention (Shabani-Jadidi 2016; Yao 2022). The second issue is research depth. Most previous studies used the visual modality in which compound words were presented visually, thereby lacking empirical evidence from the auditory modality in which compound words are presented auditorily. As mentioned above, the headedness effect can be further explored by comparative analysis of the effects of visual or auditory presentation of compound words on processing of these words. Additionally, research exploring the factors influencing compound word processing has been relatively singular, with few studies considering multiple factors affecting compound verb processing (Yu and Tian 2019).

Given these issues, this paper explores (i) how input modality and L2 vocabulary level affect the processing of Japanese compound verbs and (ii) the differences in these effects across different types of compound verbs, with the aim of answering the following two research questions.

RQ1: How does input modality affect the processing of different types of Japanese compound verbs?

RQ2: How does L2 vocabulary level affect the processing of different types of Japanese compound verbs?

Methodology

Participants

Fifty graduate students from Japanese language programs at a Chinese university participated voluntarily in this experiment. The cohort consisted of 30 females and 20 males, with an average age of 24.1 years. All the participants were right-handed and had normal hearing and either normal or corrected vision. The participants had studied Japanese for a mean of 5.8 years, and had all achieved the highest-level N1 certification in the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT). After taking a Japanese vocabulary test, the results of which were recorded, participants were assigned to either the visual or auditory group based on their score on the vocabulary test. Table 1 summarizes the JLPT N1 test scores, self-assessment scores, and self-reported Japanese usage of the participants in the visual and auditory groups. Following the methodology of Li et al. (2020), a survey of the participants’ language learning backgrounds showed no significant differences between the two groups in any measures of Japanese language ability (t = 0.02 to 1.23, df = 48, p > 0.10 in all cases). Participants received a fee of 40 RMB upon completing the experiment.

Experimental design

In the experiment, the independent variables were the type of compound verb (VV, Vs, pV, V), input modality (visual, auditory), and participants’ scores on the L2 vocabulary test, and the dependent variables were accuracy and response time in the online task to judge the appropriateness of compound verbs. Analysis based on a (generalized) linear mixed-effects model was implemented.

Experimental materials

Compound verb materials

The experimental materials (see Supplemental Material) were selected from the compound verbs included in the compound verb lexicon of the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics. Considering the difficulty level (referencing mainstream Japanese language textbooks), frequency of use [referencing the balanced corpus of contemporary written Japanese (BCCWJ)Footnote 2], length, and type of each compound verb, 120 were initially selected. Thirty-one high-level learners (whose proficiency was equivalent to that of the participants) then assessed the familiarity of these verbs [on a scale from 1 (completely unfamiliar) to 7 (very familiar)], and 47 verbs with an average familiarity below 5.0 were excluded.

To reduce the likelihood of experimental participants being unfamiliar with the target words, another group of 60 high-level learners, who had equivalent proficiency as the experimental participants, undertook a written Japanese-to-Chinese translation task including the remaining verbs. Additionally, 20 advanced learners assessed the semantic transparency between whole words and their constituent morphemes, rating the semantic relatedness on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (completely unrelated) to 7 (completely identical).

Given the higher difficulty of the Japanese-to-Chinese translation task compared to the vocabulary judgment task of this study, compound verbs with an average accuracy rate below 60% were excluded. Based on the results of the semantic transparency assessments, 48 compound verbs were finally selected, ensuring consistent semantic transparency indicators among the four types of compound verbs. There were no significant differences in the semantic relation between the constituent morphemes and the whole verb for VV (t = 0.13, df = 22, p = 0.897) and V (t = 1.46, df = 22, p = 0.158), a significantly higher relation for the first morpheme of Vs compared to its second (t = 6.47, df = 22, p < 0.001), and a significantly lower relation for the first morpheme of pV compared to its second (t = 15.75, df = 22, p < 0.001). Variance analysis of whole-word frequency, first morpheme frequency, second morpheme frequency, length (number of morae), and familiarity revealed no significant differences across the four types of compound verbs for any of the indices (F [3, 44] = 0.08 to 1.30, p > 0.10 in all cases). The experimental materials also included 36 pseudo-words in the online appropriateness judgment task. Native speakers of Japanese recorded all materials using standard pronunciation for use in the auditory modality experiments. The mean values and standard deviations of the various indices, along with examples of the experimental materials, are given in Table 2.

Test materials for assessing L2 vocabulary level

Given that all the participants were high-level learners, the vocabulary test that was used was the more challenging and widely used auditory version of the Japanese Common Academic Word TestFootnote 3 (version 2.51, Tajima et al. 2018). This test consists of 75 vocabulary semantic choice questions (1 point each, for a total of 75 points). In each question, participants first hear a Japanese word through headphones, followed by a sentence that uses the target word. The sentence is displayed on the computer screen along with three possible meanings for the target word. Participants are required to choose the most appropriate option that aligns with the meaning of the target word in the given context. They must select their answer within 30 s, although they may skip any question if they are unsure about the word’s meaning. There was no significant difference in vocabulary test scores between the visual and auditory groups [t-test; visual group: mean (M) = 64.36, standard deviation (SD) = 4.17; auditory group: M = 63.44, SD = 5.97; t = 0.63, df = 48, p = 0.531].

Experimental procedure

Because of the potential limitations associated with using response time as a measure in psychological experiments [see Crocetta and Andrade (2015)], we carefully selected the experimental apparatus and created a controlled environment for implementation. Participants were tested individually in a sound-attenuated room.

The vocabulary test was administered first, and based on the scores, the 50 participants were divided into the visual and auditory groups. The participants in both groups were assessed using the SuperLab Pro software (version 4.0, Cedrus, San Pedro, CA), which recorded their response times automatically. Practice sessions corresponding to the actual experiment were set up to familiarize participants with the experimental procedure.

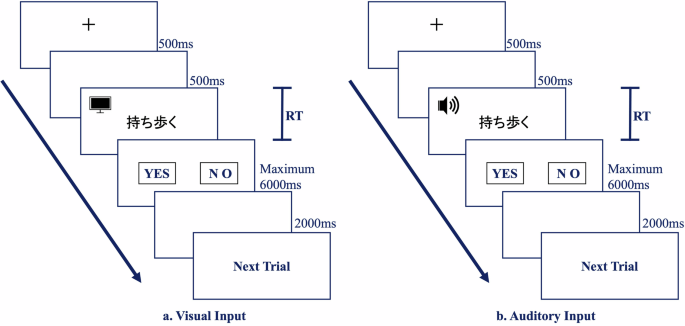

The experimental flow is illustrated in Fig. 1. A “+” appeared on the computer screen, signalling that participants would soon see (Fig. 1a) or hear (Fig. 1b) a compound verb or pseudo-word. Participants were required to quickly and accurately judge whether the compound verb they saw or heard was a real word in Japanese (Yes-Z key, No-M key). The time from the end of presentation of the compound verb or pseudo-word to the participant’s key press was recorded as the response time, and the compound verbs and pseudo-words were presented randomly by the computer to ensure that the order of presentation did not affect the results. After the experiment, a written test was administered to re-assess whether participants had truly grasped the semantics of the compound verbs presented during the experiment, and a written questionnaire was administered to gather information about the participants’ background in learning Japanese.

Experimental procedures under the visual and auditory modalities. Note: RT response time.

Results

Data manipulation and analysis method

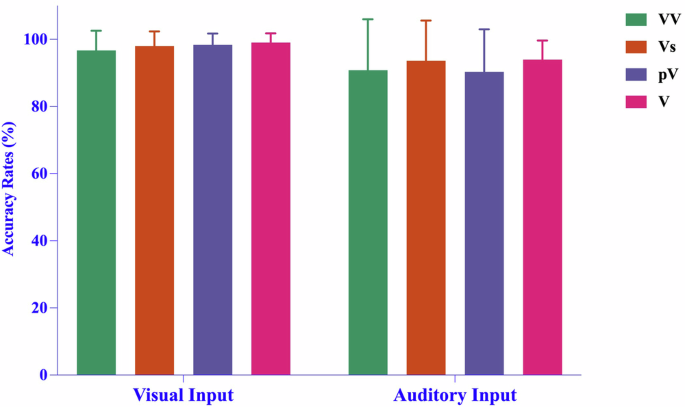

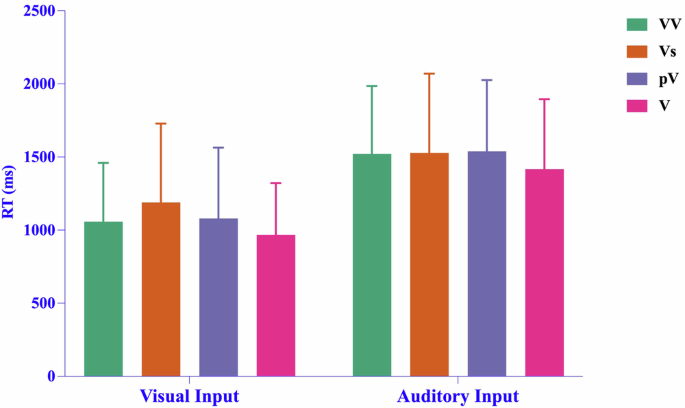

We excluded data for words that the participants did not know and no responses (26 instances) from the data analyses. Additionally, for the response time analysis, we excluded incorrect responses (117 instances) and extreme response times, both very short ( < 200 ms) and very long ( > 3500 ms) (38 instances), following the approach of Babcock and Vallesi (2015). Table 3, Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 show the mean accuracy rates and correct response times across conditions without considering vocabulary level. Additionally, to investigate whether the accuracy rates for different types are influenced by the aforementioned input modalities and L2 vocabulary level, the accuracy statistics and subsequent analyses focused solely on the accuracy rates of the target compound verbs.

Mean accuracy rates upon presentation of the four types of compound verbs in the visual modality and auditory modality groups. Note: The error bars show the standard deviation.

Mean correct response times (RT) upon presentation of the four types of compound verbs in the visual modality and auditory modality groups. Note: The error bars show the standard deviation.

Data analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.2.1, R Core Team 2022). We utilized (generalized) linear mixed-effects models with the lme4 (Bates et al. 2015) and lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al. 2017) packages. To deal with the skewed data, response times were log-transformed. Correct/incorrect responses and correct log-transformed response times were treated as dependent variables, while compound verb type, input modality, and standardized L2 vocabulary test scores, along with their interaction effects, were treated as fixed effects. The model with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) value was selected as the optimal model for fitting. The random-effects structure of the model included random slopes and intercepts (Bates et al. 2015). Jamovi software (version 2.3) was used to fit the optimal model.

Results for accuracy rates

The results of generalized linear mixed-effects model analysis of accuracy rates are shown in Table 4. The main effect of L2 vocabulary level was significant (χ² = 5.00, df = 1, p = 0.025), indicating that higher vocabulary level corresponded to higher accuracy rates. The main effect of input modality was also significant (χ² = 6.30, df = 1, p = 0.012), with the accuracy rate being significantly higher in the visual modality than in the auditory modality. There was no significant difference in accuracy rates among the different types of compound verbs (χ² = 1.90, df = 3, p = 0.593), and none of the interaction effects were significant (χ² = 1.25 to 6.15, p > 0.10 in all cases).

Results for correct response times

The results of linear mixed-effects model analysis of correct response times are given in Table 5. The main effect of input modality was significant (F [1, 52.80] = 56.14, p < 0.001), with response times significantly longer in the auditory modality than in the visual modality. The main effect of the type of compound verb was significant (F [3, 43.84] = 2.96, p = 0.043). Multiple comparisons (corrected using Bonferroni adjustment) revealed that the response time for Vs was significantly longer than that for V (t = 2.91, p = 0.034), while there were no significant differences between other types of compound verbs (t = 0.06 to 1.94, p > 0.10 in all cases).

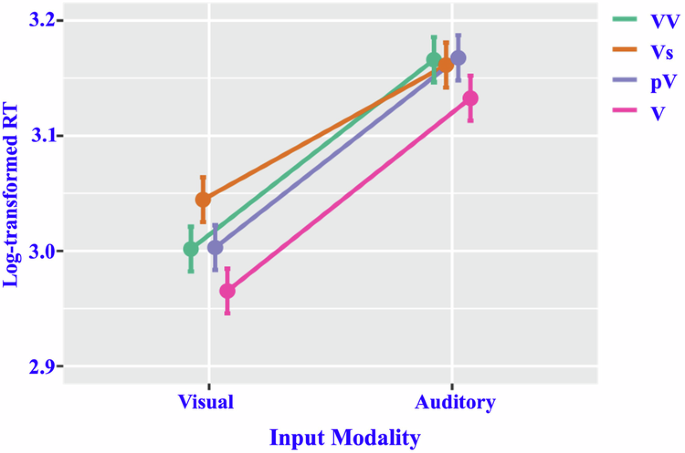

However, the main effect of L2 vocabulary level (F [1, 45.77] = 0.40, p = 0.531) was not significant. Additionally, the interaction between input modality and L2 vocabulary level (F [1, 45.77] = 1.44, p = 0.237), as well as the three-way interaction effects (F [3, 2075.12] = 0.62, p = 0.602), was not significant. The interaction effect between the type of compound verb and input modality tended to be significant (F [3, 44.37] = 2.55, p = 0.067). Simple effects tests revealed the following (see Fig. 4):

Estimated marginal means and standard errors of response times upon presentation of the four types of compound verbs by different modalities. Note: RT response time.

1) The response times for processing all four types of compound verbs were significantly shorter in the visual modality compared to the auditory modality (t = 4.79–6.91, p < 0.001 in all cases).

2) Under the auditory modality, there were no significant differences in response times among the four types of compound verbs (t = 0.05–1.68, p > 0.10 in all cases).

3) Under the visual modality, the processing response time for Vs was significantly longer than that for V (t = 3.51, p = 0.001), and showed a tendency toward longer time compared to those for VV (t = 1.88, p = 0.067) and pV (t = 1.83, p = 0.074). There was no significant difference in response times between VV and pV (t = 0.05, p = 0.963). The response times for VV (t = 1.63, p = 0.111) and pV (t = 1.68, p = 0.101) were longer than that for V, but the differences did not reach statistical significance.

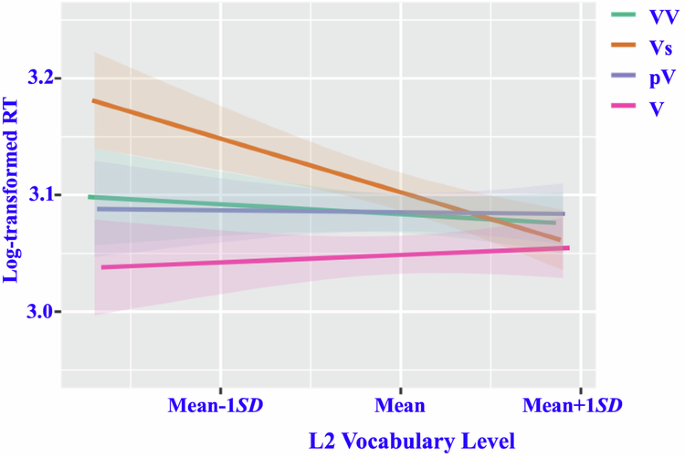

The interaction effect between the type of compound verb and L2 vocabulary level was significant (F [3, 2075.04] = 4.87, p = 0.002). Simple slope tests indicated the following (see Fig. 5):

-

1.

The correct response time for processing Vs was significantly modulated by vocabulary level, with higher vocabulary level associated with shorter correct response time (t = 2.06, p = 0.044). Correct response times for other types of compound verbs were not affected by vocabulary level (t = 0.08–0.44, p > 0.10 in all cases).

-

2.

At low vocabulary levels (Mean-1SD), significant differences in processing response times were observed among the different types of compound verbs. The processing time for Vs was significantly longer than that for V (t = 4.00, p < 0.001), and tended to be longer than those for VV (t = 1.84, p = 0.070) and pV (t = 2.00, p = 0.051). The processing time for VV was significantly longer than that for V (t = 2.14, p = 0.037). pV showed a tendency toward longer processing times compared to V (t = 2.00, p = 0.0502), with no significant difference in processing time between pV and VV (t = 0.15, p = 0.885).

-

3.

At high vocabulary levels (Mean+1 SD), minimal differences in processing response times were observed among the different types of compound verbs (t = 0.05–1.61, p > 0.10 in all cases).

Estimated marginal means and standard errors of response times upon presentation of the four types of compound verbs to participants with different vocabulary levels. Note: RT response time.

Discussion

This study investigates the processing of Japanese compound verbs as a L2, with a focus on how input modality and L2 vocabulary proficiency influence this process. To ensure the reliability of the lexical processing experiment, the materials were carefully selected to include words that were likely stored in the participants’ mental lexicon, which resulted in a generally high accuracy rate. Response times, reflecting processing speed, are influenced by the semantic transparency of the compound’s head. Specifically, compounds with a semantically transparent head are processed more quickly, whereas an opaque head can slow down processing speed (e.g., Libben et al. 2003; Libben and Weber 2014; Creemers and Embick 2022).

In this study, response time analysis revealed that Vs exhibited the longest response times. We interpret this finding as indicative of participants placing greater emphasis on processing the second verb in compound verbs. When the semantic relationship between the second verb and the compound as a whole is weak, this focus results in increased processing times. Additionally, a unified survey designed by the authors, based on the criteria established by Libben et al. (2003), revealed that learners generally rated the semantic transparency of the second verb in compound verbs highly. This further supports the hypothesis that processing Japanese compound verbs tends to center on the second verb.

Building upon the preceding discussion, the following section further explores how processing efficiency is influenced by input modality and L2 vocabulary proficiency.

Impact of input modality on processing different types of Japanese compound verbs

The response times for processing different types of compound verbs differed significantly under the visual modality, whereas these differences were not as significant under the auditory modality. These findings are in agreement with those from studies of the processing of L2 Japanese Kanji words (Matsumi et al. 2012) and collocations (Song et al. 2023), further validating the widespread influence of input modality on L2 lexical processing. Previous research has indicated that Chinese learners exhibit a phenomenon of “limping” in L2 vocabulary development, where progress in the visual lexicon outpaces that in the auditory lexicon (Yu 2013; Fei et al. 2022). Consistent with this, our results demonstrated longer response times and lower accuracy rates under the auditory modality. Notably, although instances of accuracy below 85% were relatively rare, they exclusively occurred in auditory input conditions. This finding suggests that even advanced learners of Japanese may face challenges in auditory word recognition.

The significantly prolonged processing times observed in the auditory modality suggest a potential impediment to accessing the whole-word semantics of Japanese compound verbs. Instead, these findings support a preference for a decomposed processing approach under auditory conditions. For Chinese learners, the ideographic nature of Chinese characters weakens the semantic connection between morphemes and whole words under auditory conditions compared to visual conditions (e.g., Hsieh et al. 2017; Fei et al. 2022; Song et al. 2023), thereby further lengthening overall response times. Moreover, while no significant differences in response times were found between the different types of compound verbs under auditory conditions, descriptive statistics reveal that partially transparent pV and Vs tended to exhibit longer response times compared to V. This pattern suggests that partial opacity increases cognitive load, as learners must not only retain the auditory input but also process it simultaneously. Additionally, the sequential nature of auditory input, progressing from the first verb to the second, appears to result in relatively shorter response times for Vs compared to pV. This finding highlights the impact of processing demands specific to auditory input and cognitive load in the processing of Japanese compound verbs by Chinese learners.

By comparison, under the visual modality, different types of compound verbs exhibited varied processing mechanisms, coexisting in both decomposed and holistic processing models. The response time for Vs was significantly longer than that for V, and showed a tendency to be longer than those for VV and pV. These results suggest that among the four types of compound verbs, the processing model for Vs is more inclined toward decomposition. Although the differences in response times between VV and V and between pV and V were not significant, Fig. 3 shows that the response times for both VV and pV tended to be longer than that for V, suggesting a preference for holistic processing of V, whereas VV and pV showed tendencies toward decomposition. Additionally, there was no significant difference in processing time between VV and pV, but the response time for Vs tended to be longer than that for VV. The diminished grammatical and semantic functions of the second verb in Vs likely caused an increase in cognitive resource expenditure during processing, leading to a longer overall response time. The emphasis on the second verb under the visual modality prolongs the time required for semantic access when the second verb loses its original grammatical and semantic functions.

Based on the results, we can infer that in the processing of Japanese compound verbs, learners may focus more on the second verb. At the same time, the headedness effect in L2 learners of Japanese appears to be influenced by the input modality.

Impact of L2 vocabulary proficiency on processing different types of Japanese compound verbs

The experimental results demonstrated that the proficiency level of L2 vocabulary significantly influenced the choice of processing model for Japanese compound verbs. Previous research has established that L2 learners of different proficiency levels exhibit varied processing models and intensities (e.g., Wang et al. 2010; Newman et al. 2012; Yu and Tian 2019). Our results further indicate that even among high-level learners, differences in L2 vocabulary level still impact compound verb processing. As the L2 vocabulary level increased, the response time for processing Vs shortened overall. This finding further substantiates that vocabulary level modulates the headedness effect.

In light of the influence of L2 vocabulary proficiency, the usage-based model (Bybee 2006) provides a useful framework for understanding these results. The model posits that highly frequent chunks of language, including compound verbs, are more likely to be stored and processed as holistic units by language users. Our results indicate that proficient L2 learners, who are likely to encounter compound verbs more frequently, may process these verbs holistically, as evidenced by the shorter response times for compound verbs under higher proficiency conditions.

Under conditions of high vocabulary levels, there were no significant differences in response times among the four types of compound verbs. This suggests that for learners with high vocabulary proficiency, the effect of compound verb type on processing diminishes. Under conditions of lower vocabulary levels, the response time for processing Vs was significantly longer than that for V, and showed a tendency to be longer than those for pV and VV. This result indicates a more pronounced decomposed processing model for Vs. Additionally, while there was no significant difference in processing time between VV and pV, the processing times for both VV and pV tended to be longer than that for V. These results demonstrate that among learners with lower vocabulary levels, the processing of compound verbs tends toward decomposition for Vs, and shows decomposition tendencies for VV and pV, while V leans toward holistic processing.

Because our participants were unbalanced bilinguals, they still relied on their native language for semantic access during the process of L2 lexical processing (Jiang 2000; Yang 2024). In learners with lower L2 vocabulary levels, the processing models for Japanese compound verbs were more varied and complex, with greater differences between the processing models of different types of compound verbs and a more pronounced headedness effect focused on the second verb. Conversely, in learners with higher vocabulary levels, the speed of semantic access in Japanese increased significantly, and no distinct characteristics of processing model selection were evident during the processing of compound verbs. The findings of this study may also provide evidence supporting the usage-based model, as learners with higher vocabulary proficiency likely processed compound verbs more holistically, while those with lower vocabulary levels exhibited a more decomposed processing style. Since the three-way interaction effects were not significant, these characteristics were not influenced by whether the compound verbs were presented by the auditory or visual modality, indicating that L2 vocabulary level and input modality affect the processing of Japanese compound verbs independently.

Educational implications

The results of this study indicate that in the processing of Japanese compound verbs, learners focused on the second verb, often employing a semantic decomposition strategy. This approach can lead to difficulties in quickly and accurately understanding the overall semantics of compound verbs when the semantic connection between the second verb and the entire word is weak. Additionally, these lexical processing challenges were more pronounced in learners with lower vocabulary levels and in the auditory modality. Nevertheless, mainstream Japanese language textbooks currently lack comprehensive coverage of the linguistic features and classification standards of compound verbs (Cao 2011; Chen 2022). Therefore, in educational settings, teachers should guide students to correctly understand the morphological characteristics of Japanese compound verbs. By focusing on the semantic characteristics of each type of compound verb, teachers can enhance training in holistic processing models, improving the learning outcomes for compound verbs. Compared to simple words, compound words exhibit more complex characteristics in terms of length, frequency, and familiarity. Therefore, based on theories such as the forgetting curve, it is advisable to strategically increase the input frequency of compound verbs to assist learners in achieving rapid semantic access. Additionally, emphasis should be placed on improving acquisition under auditory conditions, ensuring that compound verbs form a solid psychological reality in learners’ mental lexicons.

Conclusions

This paper presents four main conclusions. First, the processing of Japanese compound verbs exhibits a headedness effect that focuses on processing of the second verb, and this effect is influenced by input modality and L2 vocabulary level. Second, when compound verbs are presented in isolation, input modality and vocabulary level independently affect the processing of different types of compound verbs. Third, under the visual modality, the processing of different types of compound verbs evolves from decomposed to holistic models as the grammatical and semantic functions of the first and second verbs diminish. In contrast, under the auditory modality, all types of compound verbs tend toward decomposed processing. Fourth, the lower the L2 vocabulary level, the more pronounced the differences between the decomposed and holistic processing models across different types of compound verbs. Conversely, the higher the L2 vocabulary level, the more the processing of all types of compound verbs tends toward holistic processing.

This study conducted a preliminary investigation into the processing of Japanese compound verbs as a L2, revealing a tendency among Chinese learners of Japanese to place greater emphasis on the processing of the second verb. Future studies could combine eye-tracking technology to further explore the effects of input modality and vocabulary level under contextual conditions. Additionally, comparing and analysing the processing mechanisms of compound verbs between native Japanese speakers and learners can be performed to further investigate the headedness effect during the processing of compound verbs. Moreover, clarifying the impact of native Chinese on the processing mechanisms of Japanese compound verbs could provide more foundational research results for the teaching and study of L2 compound words.

Responses