Stancing solidarity: Twitter communication in Qatar during the blockade

Introduction

The State of Qatar is a country in the Gulf, which has recently hosted the FIFA World Cup 2022™, the first of its kind in the Middle East. Currently, and despite the global challenges the world is facing, ranging from the war in Ukraine and its consequences in global politics, economy, and geostrategic stability, Qatar is enjoying very good diplomatic relations with its neighboring Arab countries. In fact, it is a country that has placed great emphasis in diplomacy by acting as a mediator between conflicting parties, including its ongoing significant role in mediating between Israel and Hamas. Nonetheless, such diplomatic impact has not always been the case.

On the 5th of June 2017, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt cut their diplomatic ties abruptly with the State of Qatar on the basis of alleged accusations having to do with Qatar funding international terrorism. From that day onwards, the diverse population of Qatar, consisting of Qatari nationals, white-collar expats and numerous blue-collar workers stemming from the Indian subcontinent and from the Philippines,Footnote 1 started feeling that what they labeled as “the blockade” menaced their lives, in the sense that it imposed a danger of destabilizing the country’s military security and, as a result of this, it would threaten the country’s economy, and by extension, nationals’ and residents’ alike socioeconomic status. In order to express their anger and frustration against the blockade, Qataris and residents started using the term “solidarity” or “التضامن” [attadˁɑ:mun]Footnote 2 in local and international public discourse in and about Qatar, a fact that paved the way for the creation of an explicitly stated positive political stance vis-à-vis Qatar and its current leader, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani. As such, solidarity, especially at the initial phase of the blockade, took the shape of a multimodally constructed and digital text-mediatizeded action (cf. Theodoropoulou 2018). In other words, during the beginning of the blockade, solidarity was configured through language and through other semiotic structures of the environment, such as the layout of the space, the built environment, various fixed and non-fixed physical objects, signage, other people present in the shared space, to mention just a handful (cf. Thurlow and Jaworski 2014). Figure 1 illustrates this.

Multimodal expression of solidarity with Qatar (Source: http://www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com/contentpage.aspx?article=QBF-tournament-to-show-solidarity-with-Qatar, accessed on 10/12/2024).

Especially during the first six months of this diplomatic crisis, which was ended with the restoration of diplomatic relations and the opening of borders among the aforementioned countries in January 2021, heterogeneous people from all over the world used social media in order to express their support to the leader of the country, and the country itself by making reference to universal values, such as justice. Due to the absolute monarchical nature of the political system in the country, political stance-related references to the royal family and to the Emir himself before the blockade were very rare, if not impossible to be found in public discourse. This, however, changed dramatically at the beginning of the blockade, when people from all walks of life, namely Qatari nationals, residents, and members of the international community engaged in social media-based expressions of solidarity with Qatar and its Emir, while, at the same time, criticizing the blockading countries.

Against this political backdrop, and in combination with the fact that solidarity is a rather under-theorized concept in sociocultural linguistics (cf. Bucholtz and Hall 2005), as we show immediately below, these solidarity-related references can serve as fruitful data, which will help us understand what solidarity means, and how it is constructed in the digital textual context of Qatar. The political contextualization we have provided in this article is from our own ethnographic and sociopolitical perspective as long-term residents in Qatar, who have tried to gain a deep understanding of the political dynamics and social hierarchies shaped by tribal affiliations in the Gulf. The latter have turned out to be relevant in the analytical discussion of solidarity found here. Regarding our motivation behind writing this article, we feel that solidarity should be theorized because it is a relevant concept in people’s everyday politically oriented sociolinguistic behavior on social media. The reason for this is because it gives them the opportunity to react to and reflect on practices, choices, and initiatives that pertain to them and have an impact on their lives, directly or indirectly. In this sense, solidarity lies at the core of understanding the nexus between language and society.

What exactly do we mean by “solidarity” though, and how has this analytical concept been dealt with in sociocultural linguistic approaches? In the next section, we provide a critical literature review of the relevant scholarship, in which this study is embedded.

Solidarity in sociocultural linguistics

Over the years, socioculturally-minded linguists have conceptualized “solidarity” as a social value that competes with status and power (Snell 2018, p 665), and an “interpersonal variable” (Silverstein 2003). It has been discussed primarily in the literature on social class (Block 2013), and gender (e.g., Coates 2001), especially in terms of its correlation with power. Interlocutors can express intimacy or shared status through language. This happens via in-group linguistic markers (e.g., sounds, words, discourse markers, the use of pronouns, reciprocal naming, no naming, style shifting, and forms of address, among others). These ways have been researched from various perspectives, including corpus linguistics (e.g., Adams 2018), and linguistic anthropology (e.g., Ervin-Tripp 1972).

Literature on gender-based conversational styles suggests that both men and women in same sex discussions construct solidarity through different ways: for example, members of a female-only group express solidarity and rapport to each other via discourse markers, such as “mhm”, or head nodding, among others, whereby women achieve solidarity by being more supportive to each other (e.g. Coates 2001). In contrast, men have been argued to achieve solidarity through competitiveness (e.g., Pilkington 1998). In cross-gender interactions, women’s talk has been claimed to be small group interactions in private contexts, aiming at maintaining solidarity, while men’s talk is normed to “public referentially-oriented interaction”, where speakers compete for the floor (Holmes 1992, p 329). In the literature on language and migration (e.g., chapters in Delanty et al. 2008), one of the most important solidarity-related patterns is that children and grandchildren of immigrants tend to ‘salt’ their language with words from the old country, even if they do not speak their heritage language fluently, with the goal of consciously using community language as a way of expressing solidarity and demonstrating local sociolinguistic knowledge. In language attitudes research, non-standard language speakers have been found to score highly on solidarity measures, in the sense that they are usually perceived as more warm and friendlier than speakers of standard linguistic varieties (e.g., El-Dash and Busnardo 2001).

Solidarity, however, is more challenging to be discussed in the eternally fluid and shifting context of globalization (e.g., Blommaert 2010; chapters in Coupland 2011). In other words, mobility of people and digital connectivity, two indicative examples of the numerous dimensions of globalization, make solidarity more challenging to discuss. In alignment with the globalized “new” economy’s preference for an intensified circulation of human, material and symbolic resources (see chapters in Duchêne and Heller 2012), sociolinguists too have started recognizing how mobility and fluidity of these resources form social norms. These, we argue, are pertinent to the construction of solidarity, especially in the case of locales with fleeting and highly heterogeneous human landscapes, which host mobile people, capital, ideas and images.

Despite its central position in sociolinguistics, as we have shown immediately above, the concept itself remains surprisingly under-theorized, as it has been dealt with in a narrow way grounded in ‘sameness’, and, hence, in a highly de-sociopoliticized way. Solidarity should be theorized at this juncture in sociolinguistics because it is a relevant concept in people’s everyday politically oriented sociolinguistic behavior on social media (cf. Pérez-Sabater 2021), as it gives them the opportunity to react to and reflect on practices, choices, and initiatives that pertain to them, and have an impact on their lives, directly or indirectly. In addition, solidarity always becomes relevant, whenever there is a global scale event (usually a crisis), which is commented upon by people all over the world, especially in social media. In this sense, solidarity as an act of worlding or world-making, namely as shaping global perspectives or creating shared understandings (cf. Demuro and Gurney 2021), lies at the core of understanding the nexus between language and society. It would not be an overstatement to claim that, one of the reasons why the State of Qatar was able to overcome the perils associated with the blockade and to come out as socioculturally more coherent and solid, was the solidarity that was shaped among its population.

In terms of sociological literature, with which sociolinguistics, unfortunately, tends not to engage as extensively as it would be justified by the “socio” compound of its name (cf. Williams 2018; although, see Blommaert 2018), solidarity has been discussed primarily as “conventional” solidarity, or “group solidarity”. In conventional solidarity, people’s appeal is based on their common interests, concerns, and struggles (Dean 1995, p 132), such as the blockade imposed on Qatar; hence, this type of solidarity is pertinent to the context of our data, which is people of Qatar’s concerns about the potential consequences of the blockade on their lives, and, hence, it is a useful point of departure for the analysis found below.

The solidarity literature consists primarily of theoretical analyses by sociologists. Such an example is Durkheim (1984, as cited in Block, 2014, p 35), who makes the distinction between “mechanical” and “organic” solidarity. The former is based on high levels of tradition, social cohesion, obligation and the similarity and conformism of individuals in terms of religious practices, kinship structures and belief systems across a range of social domains. Mechanical solidarity occurs in groups that contain people who are similar in background, values, and beliefs. There is a strong and specific ‘collective conscience’, which enhances uniformity of behavior across individuals.

In the context of Qatar, which is the geographical focus of this paper, an example of such collective conscience, associated with mechanical solidarity, is the one by Bedouin (“nomadic”) and hathari (“urban”) tribes respectively that make up the approximately 333,000 Qatari citizens.Footnote 3 The latter are organized into tribes based on their patrilineal kinship system and the different values, ideologies and lifestyles they embrace. According to the relevant literature, rotating primarily around gender roles (Al-Sharekh and Freer 2021, p 143), Bedouins tend to be more conservative, namely oriented towards their past, traditions and customs, while hatharis tend to be more progressive, namely more modernized and cosmopolitan. As such, mechanical solidarity among the members of the aforementioned two groups has existed in Qatar before the 2017 diplomatic crisis and, as such, it seems to be a reasonable point of departure for the more language-based analysis that follows.

On the other hand, organic solidarity is based on low levels of the aforementioned dimensions rendering it a less tradition-bound and more occupationally and legally-based society in which the differentiation and autonomy of individuals come to be more and more dominant. Organic solidarity develops out of differences rooted in divisions of labor, and, hence, it tends to be associated with the different social classes or castes that make up the social mosaic of a given society. Even though such organic solidarity existed in Qatar before the diplomatic crisis among members of the same social classes (e.g. among blue-collar workers [cf. Theodoropoulou 2019], among Western expats, among members of Muslim communities, etc.), we argue that it has been reshaped in the form of a common-interest-in-the-security-and-stability-of-Qatar-oriented patchwork in the context of the diplomatic crisis, and this reshaping has been made in such a way as to include heterogeneous people that make Qatar’s peculiar sociodemographic fabric (Theodoropoulou 2015). Obviously, we are not arguing that these data are representative of the whole population of Qatar, because we have not analyzed all Twitter data from all Qatar-based users; nonetheless, we argue that the users, whose data are analyzed here, construct a digital safety net around the country and the leader that hosts them, has given them work, medical care, and has allowed them to earn money, and many of them are also able to send remittances back home, in order to support their families. In this sense, our understanding of solidarity is one of organic solidarity, which has been reshaped in a highly politicized way, as illustrated below.

Against this backdrop, solidarity is seen as actively and agentively constructed, namely as “spontaneous expressions that emerge from the specific forms of co-operation of individuals and groups relevant to their positions in the division of labor” (Giddens 1972, p 8). More specifically, in this paper, solidarity is dealt with as a sociolinguistically and semiotically constructed practice, realized as on online act of political stance (Barton and Lee 2013) in the context of a collective of like-minded individuals, who create to social media users a feeling of being in a social group (cf. also Rojo 2014, who has argued the same in digital acts of resistance), who express their solidarity with Qatar against the backdrop of the blockade through stance-taking (e.g., chapters in Jaffe 2009), namely through positioning vis-a-vis oneself, what is said and other people or objects.

The types of stance-taking of interest here include affective stance-taking, namely how social media users signal their feelings, and epistemic stance-taking, namely how social media users, especially tweeps, signal their knowledge and belief towards their statements. It is important to keep in mind that in social media, stance is not taken by one individual but is constantly created and renegotiated collaboratively by a networked public. As such, it is not only a linguistic act but a discursive and situated practice that should be understood in the context of online communication. The interesting research question that arises then is how solidarity is constructed in social media linguistically and semiotically. Before we discuss the emerging themes of solidarity, however, a brief discussion of our data and methodology is in order.

Methodology and data

In this paper, we take a linguistic ethnographic perspective (Copland and Creese 2015) on solidarity, inasmuch as the focus is on how situated language use constructs solidarity, and we deal with it as a digitally constructed social movement on Twitter in the tech-savvy sociocultural context of Qatar. Linguistic ethnography offers us as researchers the

“capacity to ‘tie ethnography down’ through pushing for more precise, falsifiable analyses of local language processes. On the other hand, it can also open linguistics up’ through stressing the importance of reflexive sensitivity in the production of linguistic claims, foregrounding issues of context and highlighting the primacy of direct field experience in establishing interpretative validity”.

(Copland and Creese 2015, p 4)

Falsifiability applies primarily to the qualitative section of our analysis; the basic reason why we adopt this particular take is because of the latter’s explicit commitment to reflexive sensitivity to the use of language.

Even though the blockade was discussed across all social media platforms, including, apart from Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, Snapchat, and Pinterest, we chose Twitter because it is one of the most preferred social media used in Qatar, in generalFootnote 4, and during the blockade it was used extensively as a means of spreading fake news and sharing propaganda against Qatar (cf. Jones 2019; Ritzen 2019). At the same time, it also served as a balancing platform for resisting anti-Qatar propaganda and expressing solidarity with Qatar and its Emir (cf. Oruc 2019), as is shown in the analysis below. Many tweets were also shared as hyperlinks on other platforms, such as Facebook and Snapchat, but the analysis of such interconnectivity and its repercussions for solidarity are beyond the scope of this paper, due to word limitations. In light of this, the basic research method in order to collect data for this project was the compilation of a sociolinguistic corpus (Baker 2010) from Twitter using the hashtags found in Table 1:

These hashtags were chosen because they contain the two keywords, with which people express solidarity, namely “Qatar” and “Tamim”. Hashtags combine ‘conversationality and subjectivity in a manner that supports both individually felt affects and collectivity’ (Papacharissi 2015, p 27), features that are pertinent to the enregisterment of solidarity in digital media (cf. Squires 2010; De Cock and Pizarro Pedraza 2018), hence they were used as a measurement of our data analysis. Also, the examination of hashtags is one of the most convenient means of understanding what users say about a certain topic. The corpus was collected with the help of Twitter’s Advanced Search engine, where we put the exact hashtags and their chronological range. Also, we specified that the tweets should be in English and Arabic. As a result of our search, we got tweets in Arabic, English, and a few tweets that included code-switching between Arabic and English. In this paper, however, we focus only on data in Arabic (primarily) and in English, due to word limitations. Our data here stem from two hashtags: #kulluna Qatar ‘we are all Qatar’ and #kulluna Tamim ‘we are all Tamim’.

In the #KullunaTamim Arabic tweet corpus, the majority of tweets contain embedded images and emojis. Anonymity and the sheer volume of visual data that are created, circulated and viewed by unknown audiences make it difficult to perform conventional qualitative visual analysis. This study is based on the underlying assumption that textual and visual data work together to create meaning and that meaning can be extracted from visuals, which provide context or emphasize key themes in the text (Pilkington 1998, p 234). This can happen by focusing on ‘what is physically present in a picture’ and as understanding ‘symbolic or connotative meanings’ (Pilkington 1998, p 237), based on the sociopolitical context of Qatar.

Each of the scrutinized tweets was analyzed in terms of its language and/or dialect of Arabic, emotional and epistemic stance taken by the Twitter user. The predominant dialect used in the tweets is Modern Standard Arabic (fusha). Regarding ethics when working with data from social media, some scholars (e.g. Fuchs 2018, p 390) suggest the omission of Twitter usernames as a good practice, unless the account belongs to a public figure or an institution. Aligning with this practice, we have anonymized all usernames (except for the names of the royal family members, whose tweets have been retweeted or answered) in relation to a quotation from a tweet, in order to maintain the anonymity of the owner of the postings. Since it is against Twitter’s terms and conditions to display a tweet with modifications to its original content,Footnote 5 we have provided screenshots of the analyzed tweets along with their translations in English, where applicable.

The data collection lasted from the 5th of June 2017 till the 5th of June 2019. The final date of the data collection was determined by monitoring the increments in the volume of tweets in the subsequent days of the Gulf crisis (cf. Oruc 2019: 50), and we chose the 5th of June 2019, in order to make sure that we have a long-term sample of tweets, and also to avoid the perception of cherry-picking of tweets that skews the representation of view or data. We focused on tweets from verified accounts of users, who, according to their profiles, were based in Qatar. The languages of the selected tweets were Arabic and English, as these were the dominant languages in our corpus. This also reflects the sociolinguistic reality of Qatar, where these two are the two dominant languages (cf. Hillman and Ocampo Eibenschutz, 2018: 5). Table 2 offers a description of the profiles of Twitter users, whose data have been included in the analysis:

Before our qualitative analysis, though,

Our data from Twitter, in which users tend to draw on repertoires of semiotic resources to communicate with one another, include primarily language, hashtags, images, emoticons, and videos, which are used in combinations and in tandem in their tweets. Such an integrationist perspective on digital communication (cf. Harris, 2009) puts the emphasis of analysis on understanding how users integrate their own semiotic activities with those of their interlocutors. This is an important but under looked dimension in solidarity-related sociolinguistic scholarship so far, so this paper is an attempt to fill in this lacuna.

For the qualitative part of our analysis, we identified emerging themes associated with solidarity, on the basis of which our analysis has been structured (see below). We did not analyze in depth all collected tweets due to their volume; the 484 tweets we chose to scrutinize more closely under each of the identified themes found below (Table 3) were the ones that were more intelligible to us as ethnographers and also as long-term residents of Qatar, inasmuch as they offered a clear, i.e., uncontroversial, message that could be understood and ethnographically scrutinized by us as researchers. In this sense, we acknowledge the fact that the tweets analyzed in the qualitative section might be seen as biased. However, we did our best to reduce this bias by including data both in Arabic and in English reflecting the two most highly frequently used languages found in the aforementioned hashtags. In terms of the gender of Twitter users, we found that the majority of tweets were from self-identified as male users based on the profile names, and this is the reason why we focused on male user tweets. Please note that one of the tweets analyzed below has been made by a male user but consists of a retweet made by HE Sheikha AlMayassa Al Thani. A discussion of gender-based differences in solidarity tweets, even though it is interesting in its own terms, due to word limitations is beyond the scope of this paper.

Clouding solidarity in the Arabic and English corpora

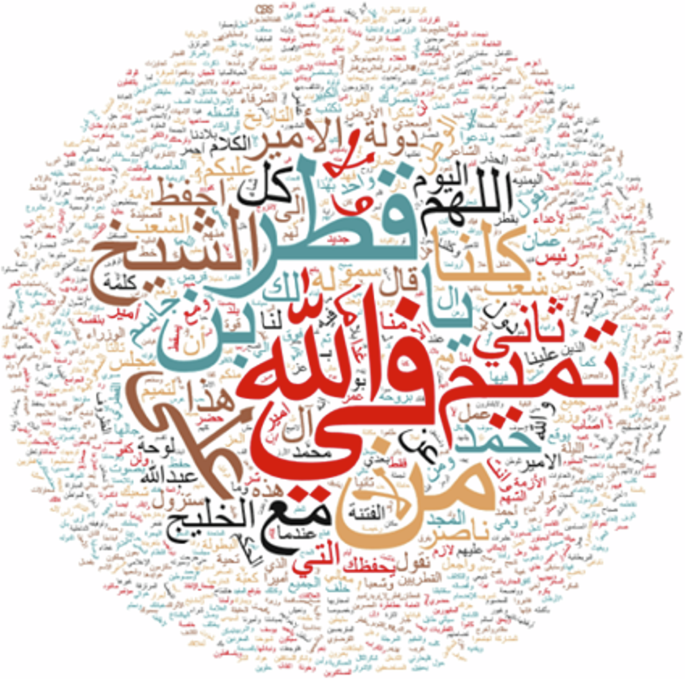

Our first exploratory analysis was a simple word count. We generated word clouds in both our English and Arabic corpora as a data visualization technique used for representing text data in which the size of each word indicates its frequency and, subsequent, importance. The tweets were mined with the help of R and frequency word clouds were created for both Arabic and English sub-corpora.

Following Oruc (2019 p 51), we parsed our data to make the large number of tweets in the original data set (n = 238,174) more manageable and to create a sample for close qualitative analysis. The sampling was undertaken through a three-step process. First, a data set was established from the original to include only one copy of a tweet retweeted twice and more. This was done to ensure an equal opportunity of selection for all unique tweets in the data set. For example, the tweets of influencers, namely tweeps, who have larger numbers of followers, were not privileged over those whose tweets are not retweeted due to low follower numbers. This process resulted in 12,739 duplicate groups and 31,995 single items (i.e., those that were not retweeted). Second, one copy of a tweet retweeted twice and more from each duplicate groups and all single items were combined to form a new data set resulting in 86,610 tweets published by 12,493 unique accounts, which included: (1) tweets that had been widely circulated and (2) those remaining at the periphery due to a lack of circulation. In this way, we made sure that our sample was balanced, inasmuch as it included both ‘core’, namely widely circulated, and ‘peripheral’, namely less circulated data. Finally, computerized random sampling through the use of R was used to construct a representative data set of 500 tweets. This data set was initially screened to remove tweets that are: (1) no longer available (because either the account is no longer available or the account is set back to private), (2) published with the examined hashtags by users from opposing countries to attack Qatar, and (3) bots (i.e., automated accounts). This yielded a final data set of 484 tweets. The generated word clouds with the most frequently used terms are found in Figs. 2 (Arabic) and 3 (English).

Word frequency-based word cloud for Arabic data.

Word frequency-based word cloud for English data.

A frequency word cloud shows how frequently each unique lexical item occurs within the corpus. The frequency measurement aims at offering a clear descriptive linguistic structure of the concept of “solidarity”, which we elaborate on in the more qualitative aspect of our analysis below. Echoing findings in many corpora, in our initial results, the most frequent features were primarily grammatical or “function” words, such as the prepositions [fi:] “in” and [min] “from”. Since these can obscure—at least on a surface level—discourses that might be of interest, we excluded all word-classes but nouns, verbs, and adjectives, leaving results that could give us a clearer picture of the most important solidarity-related themes within the corpus.

In the Arabic word cloud, the three most frequently used nouns are [qatʕʌr] “Qatar”, [tami:m] “Tamim” and [ʔalʕlʕɑ:h] “Allah”, while in the English word cloud the most frequently used words are verbs, such as ‘says’ and ‘overcome’, as well as nouns, such as “obstacles” and “Gulf”. In both word clouds, some of the most frequently used words are nouns. These include “Allah”, whose name is used in people’s tweets pertinent to the blockade, and the protagonists of the blockade, namely “Qatar”, and H.H. the Emir of Qatar, Sheikh “Tamim”. “Allah” is one of the most frequently used words in the Arabic word cloud because it is used in daily Muslim prayers.

Action verbs are also included that describe practices that have been taking place during the blockade, such as using diplomatic (to mediate among the countries involved in the blockade), political (to communicate information relevant to the blockade), and social words (to share emotions that have been triggered by the blockade). Apart from “saying”, which indexes the aforementioned practices, the verb “overcome” indexes optimism that the blockade would soon come to an end.

Comparing between the Arabic and the English word clouds, the fact that in the former the most highly frequent words are nouns can be argued to mean that in Arabic, people tend to religionize their tweets by referring to Allah and to also individualize and personify them by referring to the country and its leader. The generated word cloud suggests that people consider important both Allah and Sheikh Tamim, even though according to Islam, no human being can be identified, i.e. considered to be at the same level, with Allah. In the Holy Qur’an, there is an Ayah that forbids the association of people with the divine status of Allah:

“قُلْ يَا أَهْلَ الْكِتَابِ تَعَالَوْا إِلَىٰ كَلِمَةٍ سَوَاءٍ بَيْنَنَا وَبَيْنَكُمْ أَلَّا نَعْبُدَ إِلَّا اللَّهَ وَلَا نُشْرِكَ بِهِ شَيْئًا وَلَا يَتَّخِذَ بَعْضُنَا بَعْضًا أَرْبَابًا مِّن دُونِ اللَّهِ ۚ فَإِن تَوَلَّوْا فَقُولُوا اشْهَدُوا بِأَنَّا مُسْلِمُونَ“ (3:64)

Translation

‘Say, “O People of the Scripture, come to a word that is equitable between us and you – that we will not worship except Allah and not associate anything with Him and not take one another as lords instead of Allah.” But if they turn away, then say, “Bear witness that we are Muslims [submitting to Him].”’ (3:64)Footnote 6

The verse quoted from the Quran forbids the association of any person or thing with the divine status of Allah. An Islamic reading of the word cloud would translate into Allah’s favoring of Sheikh Tamim for the prosperity of Qatar and Tamim’s subsequent glorification.

On the contrary, in the English word cloud, the combination of verbs and nouns paints a more contextualized picture of the blockade, inasmuch as people locate their talk in the region “Gulf” (instead of the country) and they focus on actions that (did/will) happen, instead of agents.

Trying to explain this difference in the linguistic structure of solidarity, we argue that the Arabic corpus reflects a more agent-oriented religious and political understanding of solidarity by Twitter users found in Qatar, which is an Islamic absolute monarchical country, where the religious agent is Allah and the political leader is Sheikh Tamim. In that sense, the Arabic corpus renders the concept of “solidarity” or ‘التضمن’ [it-taðʕɑ:mun] more as affective political stance, since it associates solidarity as expression of strong support to Sheikh Tamim and to Qatar on religious grounds. On the other hand, the English corpus “views” solidarity more as a set of political and diplomatic actions that have been taken, in order to end the blockade without neglecting, however, the emotional stance that these actions have triggered. This clear distinction between agent and action-based structures in both corpora indexes the two dimensions of solidarity, namely feelings in favor of and actions to honor and protect Qatar and the Emir, which are further delved into immediately below.

Tweeting discourses of solidarity

Taking a more politicized stance vis-à-vis solidarity, we argue that solidarity constructed in Qatar in online communication during the blockade pertains to the level of political and ethical interests of people. It is also characterized by impromptu dynamism and collective inventiveness, which through social media can be disseminated in the local and global digital sphere. This means that people can produce solidarity as different ways of challenging oppression, which has taken the form of the blockade imposed on Qatar. Political articulation of solidarity is shaped through diverse practices, which, according to their frequency of occurrence in our corpus (see Table 3), include religion, culture, society, poetry, psychology, and grass roots digital initiatives.

Many—if not all—of the 484 tweets are pertinent to more than one themes (e.g., the poetry ones are enmeshed with culture); for ease of reference, however, we decided to categorize them under the theme we felt was the most pronounced one they contained. One indicative tweet, which has been selected according to the criteria we discussed in the methodology and data section above, from each of these themes is analyzed below.

Religion-based solidarity

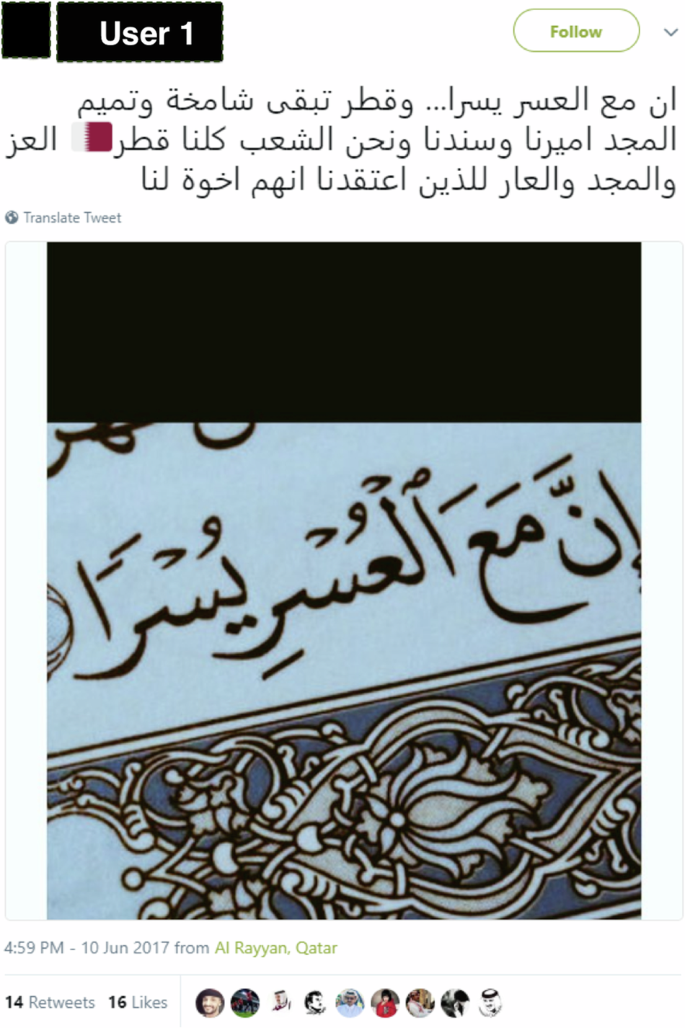

Solidarity is constructed by the Twitter users through taking a religious stance on the blockade in the 223/484 tweets of the corpus. This echoes the high frequency of the word “Allah” in the quantitative analysis found above. Twitter users align themselves with Allah by making intertextual references to the Holy Qur’an, a fact that makes solidarity stronger, and morally and ethically binding. To illustrate this idea, we provide an analysis of the following tweet, which has a resemiotized (Iedema 2003) Qur’anic verse, used as a promise. This type of promise from Allah usually evokes feelings of comfort, reassurance and, most importantly, relief after hardship. More often than not, people use it as a reminder of that promise. The relevant text is ‘ إِنَّ مَعَ الْعُسْرِ يُسْرًا translating to ‘indeed, with hardship [will be] ease.’ (The Qur’an Ash-Sharh 94:6) (Fig. 4).

Religion-based solidarity example.

Literal translation: Quranic verse: “Indeed, with hardship [will be] ease”. And Qatar will remain sovereign and Tamim the Glorious, our Emir, is our pride and support and we, the people, are Qatar, the glorious and prestigious. And shame to those whom we thought to be our brethren.

Despite the adversity of the blockade, User 1 promises the people of Qatar that, once the adversity of the blockade passes, comfort, ease and serenity will return. These are features of solidarity, which, framed in religious terms, are presented as morally and ethically bound to happen in the future.

There is praise to H.H. Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, who is the current Emir of Qatar, and who enjoys the full support of both Qatari nationals and residents alike in his attempt to reduce the cost of the blockade on Qatar and keep the people safe and content (cf. Amin and Zarrinabadi 2022: 12; Oruc 2019: 53–55). On the other hand, User 1 implies in his tweet that closeness among Muslim countries has been compromised due to the betrayal felt by Qatari people during the blockade. He denounces the blockading countries in an indirect way by highlighting the betrayal of the blockading countries, which are not named. Such an erasure of their names is because of the appalling breach of the brotherly status of Muslim countries, which, inter alia, has resulted in the splitting of actual families and the breach of brotherly ties among Arab countries.

Towards the end of the tweet, the calm tone offered as words of resilience to the people of Qatar shifts into humiliation of the blockading countries. This humiliation comes as the other end of the use of religious tone, which functions as comforting Qatar-based Twitter users, and it serves as a moral and ethical warning against the people who support the blockade; the latter is indexed through the word “shame”, which frames the blockading countries’ effort to breach the ’umma (Suleiman 2006), namely the ideology that unifies all Arab Muslims on the basis of their religion and language, in immoral terms. The appeal to the highest religious authority, which in this case is the Holy Qur’an, is represented both linguistically, through the verse, and semiotically, through a screenshot from the Holy Qur’an. This reference to the Holy Qur’an creates a pledge as a reminder to people of Qatar to stand united and support the country’s Emir in his efforts to deal with the financial, and sociopolitical consequences of the blockade.

Overall, in this tweet solidarity is constructed as a religion-based framework of action, and, hence, as a moral commitment, which is bi-directional: from the Emir to the people of Qatar and vice versa.

Culture-based solidarity

The digital solidarity movement with Qatar during the blockade, as it has been encoded in the 106/484 tweets of our corpus, has had a tangible and significant impact on the Qatari culture, inasmuch as it has triggered cultural change. More specifically, after the blockade, there has been a notable spike in the choice of the name “Tamim”, to name newborn male babies in the country (Fig. 5). The workings of the rise in the choice of the name “Tamim” for newborn males in Qatar is analyzed below:

Literal translation: A privilege and a badge of honor for everyone named after this name named after Sheikh Tamim).

User 2 praises all children that have been named after H.H. Sheikh Tamim. According to Table 4, 314 babies were named after the Emir of Qatar during the period from the beginning of the blockade till the end of October 2017, according to the attached image, which is a headline from Al Sharq newspaper with data from the Ministry of Health.

The tweet highlights the cultural repercussions of the blockade, inasmuch as H.H. Sheikh Tamim through his actions is seen as a role model for the population to the point that people name their sons “Tamim”. People take an emotional stance in favor of their leader. The underlying assumption behind this practice is that the glory, heroism (cf. Theodoropoulou 2025), and wisdom attached to H.H. Sheikh Tamim (cf. Oruc 2019: 54), due to his efficient leadership during the blockade, should be passed to the next generations of Qatari males, in order for the latter to enjoy the self-esteem, which is currently and will be, in the future, associated with the name “Tamim”.

By identifying their children with Sheikh Tamim, the parents, whose children are praised in this tweet, express solidarity to their political leader through the tangible action of granting them his name, a decision that will have an everlasting impact on these children, inasmuch as their parents’ commitment to the leader of Qatar will be always reflected on their onomastic choices for their sons. Such long-term expression of solidarity indexes the depth of appreciation Qatari families wish to express to their leader.

Society-based solidarity

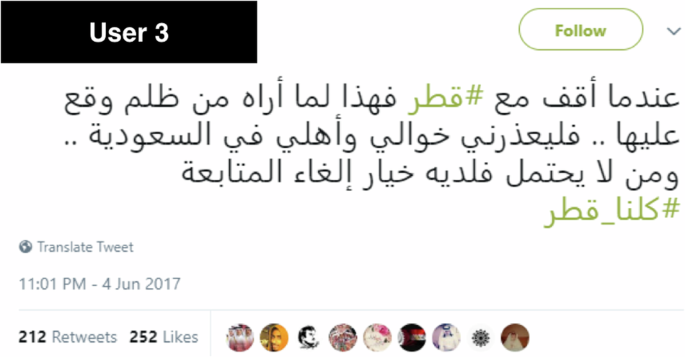

During the blockade, it has been observed that social groups, which in the past have either not interacted with each other at all, or they have not been on very good terms, have been brought together in the context of the solidarity movement in Qatar against the blockading countries, as it is evident in the 99/484 tweets of our corpus. In this sense, solidarity has interethnic and intertribal dimensions, apart from religious, psychological and cultural ones. The following tweet is a case in point (Fig. 6).

Literal translation: When I side with Qatar, this is because of the injustice I see has befallen it. So let my uncles and family in Saudi forgive me, and whoever can’t tolerate this has the choice to unfollow (me).

In this tweet, User 3 takes an explicitly positive stance vis-a-vis Qatar by sharing his moral duty to express solidarity with Qatar. At the beginning of his tweet, he expresses his solidarity through taking epistemic stance vis-a-vis Qatar, inasmuch as he explicates a causal relationship between cause and effect: “because injustice has hit Qatar, I do a just thing by standing with Qatar”. He frames his stance as an argument, whose basis is the word [δʕʊlʕm], which means ”injustice”. He unofficially represents a country, Kuwait, which is not immediately involved in the blockade, but all the same he feels guilty, because he feels that by siding with Qatar he undermines his allegiance to Saudis.

There seems to be an internal conflict between his patriotic duties and his moral values. He feels shame, while he is doing what he considers to be “the right thing”. User 3, who is a Kuwaiti national, pledges allegiance to Qatar and its people against a Saudi act of aggression. Such a situation reflects a general sociocultural tendency among Gulf-based Arabs, who in case of an internal conflict, like the one found here, need to take sides and, as a result of this, to split. This need to take sides can explain the use of the conditional in the Arabic tweet (“when I side with Qatar…)” Because Gulf-based Arabs feel the need to take sides, they use the conditional to justify their stance. The underlying assumption here is that there is an injustice, so we side with Qatar. The triggering of their tribal instinct is very strong and can lead to an absolute cut of the ties among members of a tribe, which is what we are currently witnessing in the context of the blockade imposed on Qatar.

To mitigate this undermining and, hence, to avoid potential imprisonment (due to a law that was in place during the period of the blockade, according to which Gulf-based Arabs were not allowed to express their support for Qatar in social media),Footnote 7 he shifts to emotional stance through an apostrophe—apology to his family in Saudi Arabia indexed through the verb “pardon”, which functions as a mitigation device. This allegiance to Saudis is based on the concept of ’umma, which has been already discussed above, and which has been broken due to the blockade. The allegiance to Saudi could also derive from the GCC slogan: “we are one” (one Gulf country, one community). The generations of the ’80s and ’90s specifically grew up with that ideology. GCC ties grew even stronger after the first Gulf war, in which Saudi Arabia claims to have had a major role in liberating Kuwait.

This is another reason for being apologetic, for some might consider the Kuwaitis’ siding with Qatar as being ungrateful. The use of apology indexes an internal conflict between the Twitter user’s tribal ties and his moral values; the former translate into all Arab Muslims being one nation and acting as one, without divisions and embargos, while the latter include his ascertaining of prioritizing fair treatment of Qatar in the context of what he sees as an unfair and repressive political treatment of the country. Through the use of [faljaʕδurni:] (= so forgive me), User 4 indexes his feeling guilty, because he feels that he is undermining his expected patriotism vis-a-vis Saudi Arabia.

Overall, he seems to engage in a binding through redefining and re-establishing his tribal alliances reflecting, in this sense, a similar more macro-level process that has been happening all over the Gulf among family members during the blockade.

Poetry-based solidarity

As a social movement, solidarity has also drawn on poetry as a means of aestheticizing the call for people to join. The use of poetry, as found in the 37/484 tweets of our corpus, echoes a general tendency there is, at least in the Arab world, for poetry and politics to be enmeshed with involving people in sociopolitical movements (Fig. 7).

Poetry-based solidarity example.

Literal translation: We sacrifice ourselves for the sand you walk on and we hit like the waves of the sea, and if we strike, by God we strike with precision.Footnote 8

User 4 quotes a few lines from a patriotic poem, which is an encomium to H.H. Sheikh Tamim and Qatar. It has been popularized into a song written by Sheikh Mohammad Bin Falah Al Thani.Footnote 9 Drawing on Arabic poetry motifs pertinent to sea waves, User 4 takes an intertextually poetic stance to express his solidarity with Sheikh Tamim directly, evident through the use of the second person singular (which is the [ka] in [turɑ:bika]). User 4 presents himself as addressing Sheikh Tamim on behalf of all people in Qatar, indexed through the “we” inclusive found in the word [nafdi:]. [ʔinnahu] here is used to emphasize the precision of the strike. [ʔinna] is an assertive marker here, and [hu] is a pronoun that refers to the noun directly preceding it. In this tweet, the noun directly preceding it is ‘the strike’. This is an emotionally loaded vivid image drawn from a nature-based acoustic image. The hitting is presented through the trope of simile as a never-ending wave crashing. This is presented as a fact in the first two verses of the poem. The last two verses of the poem present a condition for acting against the blockade. More specifically, [walʕlʕɑ] is used as a marker of promise, like in the first tweet analyzed in this paper, and as a way of emphasizing that the striking will be fatal, because it will be straight to the heart of the opponents. In this sense, the tone of the poem is patriotic, as the latter is addressed to the country of Qatar, and heroic, as it addressed to Sheikh Tamim. At the same time, in these verses there is a hyperbolic and simile-based expression of admiration, which is based on the idea of self-sacrifice indexed through the words [fideitak] and [nafdi:].

Overall, echoing the first tweet, the poem contains religious footing in order to substantiate and validate religion through the use of [walˁlˁɑh]; the latter is used as an argumentative strategy rather than as a fully-fledged ideology to reinforce the vividity of the commitment to the action of hitting, which enhances the strength of the hitting.

Psychology-based solidarity

Apart from drawing on religion, culture, society, and poetry, Twitter users have been found to exert pressure on other Twitter users to join in the expression of solidarity with Qatar. Such a psychological pressure, found in 11/484 tweets of our corpus, becomes evident immediately below (Fig. 8).

Psychology-based solidarity example.

User 5 has posted a reply to H.E. Sheikha Al Mayassa’sFootnote 10 tweet about Germany’s explicit siding with Qatar, which is the first country in the EU that supported Qatar during the blockade. She frames Qatar allies as loyal, and in this sense, she glorifies and foregrounds Qatar’s allies, while erasing the blockading countries and their supporters. User 5 foregrounds Qatar’s supporters by attributing to them loyalty, one of the cornerstones of the Arab identity. Loyalty is built on trust. The blockading countries severed the ties of trust and, hence, their loyalty has been cast into doubt. Before the blockade, all countries of the Arab League were considered to belong to the ’umma, the ideology of one nation pertaining to all Muslim and Arab countries, namely a nation whose members are united through Islamic brotherly ties. The sub-text of the tweet is that the blockading countries have betrayed the ’umma, and therefore, whichever country supports the blockading countries cannot be seen as loyal. In light of this, we could argue that this tweet is used to exert psychological pressure to both people and states to support Qatar, otherwise they will be considered to be disloyal, and, hence, they will be ostracized from the ’umma community. The pressure becomes more effective through the internationalization of the idea of collectivization of loyal people, which becomes evident through the reference to Germany.

The hashtags found underneath the tweet, especially the #Dont_block_Qatar one, serve as a further means of exerting pressure on Twitter users to join the solidarity movement, inasmuch as standing with Qatar is constructed as an obligation rather than a choice (evident through the use of the imperative form ”don’t block”). The use of hashtags containing the word “Qatar” serves as a way for the tweet to reach a wider audience, and hence for this psychological pressure on Twitter users to stand with Qatar to be extended.

In this sense, it can be argued that by drawing on psychology, Twitter users are trying to render their expression of solidarity with Qatar denser, in the sense that they construct solidarity with Qatar not as a desideratum but as a need, which will help them reassert their position in the ’umma, a task that carries gravity in the lives of Muslims.

Grassroots politics-based solidarity

In 8/484 tweets of our corpus, we have noticed that some Twitter users tend to turn people against one another by using their influence, which is partly the outcome of the high numbers of their followers. In this way, their tweets are rendered into potential influential acts.

In the following tweet, User 6 tries to turn the Qatari public against a group of Saudi and Emirati influencers, because many of them stood in support of their country leaders, in spite of the fact that the latter are seen as spreading hatred (Fig. 9).

Grassroots politics-based solidarity example.

Literal translation: Do not forget the people in this list, Qataris (index pointing down emoji), the list of shame (;) may God turn their faces black (punish them).

User 6 offers a list of shame comprising a total of 12 Saudi and Emirati actors, singers, and entertainers, who are social media influencers, and he encourages people, who side with Qatar, to boycott them. He takes an emotionally loaded stance by using the term [muharrid͡ʒ], which means “clown”, namely a non-serious person. One of the clowns he mentions is Abu Jarkal, who is a Saudi comedian known for his stylizations for comedic effect. At the beginning of the blockade, a video-based compilation of Abu Jarkal’s clips, posted on his Snapchat and Instagram personal accounts, was published on YouTube,Footnote 11 whereby he not only pledged his allegiance to King Salman, the King of Saudi Arabia, but he also emphasized the brotherly ties between the Saudi and the Qatari peoples. At the same time, he alienated the Qatari government from the rest of the Gulf monarchies.

Under these circumstances, through the documentation of the wrongdoings of the aforementioned 12 people, User 6 belittles and essentially ridicules the social media influencers’ social status, profession, and craft. In the end, User 6’s goal is to encourage people to show solidarity with Qatar by boycotting the aforementioned artists and in this way, by not contributing towards the support of these people’s negative stance against Qatar. This is a grassroots-blacklisting act (cf. Hachimi, 2016), which functions, simultaneously, as a call for resistance against powerful social media influencers from Saudi Arabia and the UAE, who, according to User 6, employ propaganda techniques against Qatar (cf. Jones 2019). He enhances this shaming by praying that their sins will result in their darkened faces on Judgment Day, which means that they will be punished. The expression of blackened face relates to the person who does bad deeds and disobeys the teachings of Islam. A person having a blackened face is a marker of a Muslim banned from God’s forgiveness and, subsequently, functions as a marker of that person’s punishment in light of their bad deeds. More specifically, on Judgement day (very significant for Muslims), the ones who disobeyed the teachings throughout their lives are brought back with blackened faces, whereas the ‘good’ ones are brought back with white faces. In the context of the blockade, the breach of brotherly ties is seen as a sinful act, which justifies the darkening of their faces, according to User 6.

Concluding discussion

In this paper, we have presented a reflective concept of solidarity as part of people’s textual choices on Twitter, which seems to be an agent-oriented religious and political take on solidarity rendering the concept of ‘solidarity’ or ‘التضامن’ [attadˁɑ:mun] as affective political stance.

After we identified and analyzed with the help of R the linguistic structure of the concept in both our Arabic and English corpora, we found that the Arabic corpus contains a more agent-oriented religious and political take on solidarity rendering the concept of ‘solidarity’ or ‘التضمن’ [it-taðʕɑ:mun] more as affective political stance, while the English corpus contains a view of solidarity as an action-based structure, namely as a set of political and diplomatic actions that have been taken, in order to end the blockade without neglecting, however, the emotional stance that these actions have triggered.

In order to better understand what exactly this political stance means, we analyzed illustrative tweets across the dominant themes of religion, culture, poetry, society, psychology, and grassroots politics, which were found to be the most frequently used ones in our corpora. In this approach, we have looked at the contextual aspects of solidarity and, hence, in an attempt to push the boundaries of solidarity by going beyond established approaches to sociolinguistic analysis thereof, we argue for a more politicized and situated sociocultural linguistics of solidarity, namely an approach that acknowledges limits and complexity by taking into consideration the political context, in which it is created. Emphasis is then on the discursive practices and relationships that intersect at specific points in specific lives, which, in this case, include Qatari and expats’ thoughts and reactions to the blockade imposed on Qatar in June 2017. These take the shape of a solidarity stance, which in turn has been argued to be a practice that acts as a “localizing move” and a “globalizing connect (Barton and Hamilton 2005, p 31) at the same time.

More specifically, solidarity has been constructed as a reactive movement against actions perceived as oppressive and defamatory by the blockading countries, which means that it is an attempt to resist oppression. Such a movement takes the form of both expression of emotions and conduct of tangible action, produced by a combination of passionate political elites in Qatar, and it is forged through the tweets of Qatari nationals and some residents alike, who have much to gain in the short term by breaking the blockade. In this sense, there is construction of organic solidarity, presented as an ideal of sociolinguistic coalition whereby already existing locally based hierarchical relations among individuals and social groups are transformed. Through this analysis, solidarity in the context of Qatar blockade can, thus, be seen as a grassroots activity from below, i.e. from the level of lay people, who direct their anger, frustration and disappointment through the channel of social media. The latter, however, also incorporate the voices of members of the extrovert royal family of Qatar, which are in accordance with the former; in this way, the alleged hierarchy between these different social segments is annihilated, and in such a situation of “context collapse” (cf. Moore 2019), these groups create for themselves new ways of relating on the basis of common values, thoughts and ideologies they represent (cf. Amin and Nourollah Zarrinabadi 2022, who have found a similar pattern in the linguistic landscape of Qatar during the blockade). These translate into a(n) (ephemeral) digital collapse of social hierarchy between the royal family of the country and the lay people on the basis of everyone living safely and without disruptions in their daily business.

As such, solidarity creates circumstances of redefining political communities and different ways of shaping relations among people. The political community here is constructed as inwards-looking, inasmuch as it focuses on the enhancement of the already existing ties among its members, through the erasure of until very recently divisive labels that pertain to Qatari culture, society and religion, such as hatharis (i.e. “urban”) and Bedouins (i.e. “nomads”), “royals” and “common” people, “Qataris and “non-Qataris”, and “sunni” and “shia” Muslims. Seen like this, it has grown to become more organic with the collapse of political hierarchies. In this sense, solidarity is defined in terms of two network properties: the relative directness of ties among actors, and the homogeneity of those ties. The vast majority of tweets come from Qatari males, a fact that suggests that this collapse of hierarchies is relevant to them as a strategy of creating solidarity, and not to females, whose representation in our sample has been very scarce. This is a finding that brings the way solidarity is constructed in this male-based corpus closer to the female-related sociolinguistic findings on solidarity, which is associated with rapport and lack of hierarchy.

Similarly, the majority of tweets come from hatharis, something which justifies the finding of hierarchy collapsing, given the tribal affiliation of them with Sheikh Tamim. The difference between hatharis and Bedouins in our corpora, however, is not big enough to allow us to jump into conclusions about any potential differences in terms of expressing solidarity as a political stance between the two main tribal groups of Qatar.

Solidarity has been also found to discursively open up new political terrains and possibilities. With respect to the former, our data suggest that, at least at the level of Twitter-based communication, an ephemeral solidarity-driven community is created on grounds of religious, cultural, poetic, social, psychological, and grassroots political relationships. People frame their solidarity along the lines of these themes, rendering it the digital expression of what could be called a common-interest-in-the-security-and-stability-of-Qatar-oriented patchwork in the context of the diplomatic crisis. In other words, because the heterogeneous, and hence peculiar sociodemographic fabric felt that their security and financial stability was compromised during the blockade, these people felt the need to express their solidarity with the country and its leader based on religious, sociocultural, political, and psychological needs.

Sometimes there are overlapping undertones of themes of solidarity. For example, in the case of poetry-based solidarity, the poem contains religious stance taking in order for the tweeps to substantiate and validate religion through the use of [walʕlʕɑ]; the latter is used as an argumentative strategy rather than as a fully-fledged ideology to reinforce the vividity of the commitment to the action of hitting, which enhances the strength of the hitting. Religion, as has been analyzed in the tweets of Users 1 and 4, seems to create what could be called “promises of solidarity”.

As such, organic solidarity that has been found in the analyzed data set is also ‘conventional solidarity’ (Dean 1995, p 114), which grows out of common interests and concerns. On the one hand, conventional solidarity arises out of the shared traditions and values uniting a community. In our data, we have found these to include a range of cultural dimensions or values including loyalty, piousness, self-sacrifice, justice, appreciation, and honesty. On the other hand, conventional solidarity refers to members of a community, whose members are involved in a common struggle or endeavor. In each case, the expectations of members are given, whether rooted in traditional values, or shaped by the blockade. Conventional solidarity, then, takes its sociolinguistic form from a shared adherence to the common belief that unites people, which is the blockading countries’ need to respect Qatar’s sovereignty. An illustrative example of this from our data is User 5, who identifies all loyal people with people, who stand with Qatar during the blockade and, by extension, this means that whoever is not siding with Qatar is seen as disloyal.

The significance of the project translates into a theoretical contribution to an understanding of how solidarity is constructed as a textual phenomenon in digital communication under the particular condition of the blockade against Qatar, a demographic and sociolinguistic context which is rare to be found elsewhere in the world: an absolute monarchical state, where, during the blockade, there was a major support vis-a-vis the Emir of Qatar on behalf of the diverse social segments forming the population of Qatar. In this sense, the paper does not offer an authoritative generalization of solidarity in sociolinguistics; rather, it argues for a close and context-rich approach to the concept. In order to make wider sociolinguistic claims about solidarity, we would need case studies from countries all over the world focusing on transnational and translingual social movements, an idea that I offer as a potential future research direction.

Along the same lines, whether this ephemeral and digitally constructed solidarity will translate into a more permanent long-term offline solidarity is something we will have to monitor and see how it will develop.

Finally, in terms of its more practical implications, this paper can be seen as a guide for the Qatari government to develop strategies in strengthening internal solidarity and resilience against any potential future crises. Along the same lines, it can also create a positive narrative for Qatar, whereby media will be used to promote stories of solidarity and resilience, helping to shape public perception of Qatar in the global sphere and maintain morale of the people, who live and work in the country.

Responses