Fast adaptive optics for high-dimensional quantum communications in turbulent channels

Introduction

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) allows two parties to generate a shared secret key between themselves by taking advantage of the properties of quantum systems1. Since the introduction of the first protocol by Bennett and Brassard2, many QKD protocols have been explored theoretically3 and experimentally4. The original implementations relied on encoding schemes using light’s polarisation degree of freedom, constraining the quantum states to a two-dimensional vector space. However, higher-dimensional QKD protocols, employing unbounded photonics degrees of freedom, were suggested to increase information density per carrier5,6. There are many photonic degrees of freedom in addition to polarisation, which can be used for encoding information, including frequency, vector modes, and time bins7,8,9,10. Here, we employ the spatial structure of the lights transverse mode through the orbital angular momentum (OAM), which has been studied in diverse settings, including free-space11,12, fibre13,14, and underwater15,16,17,18. Optical beams carrying OAM are characterized by an azimuthal-dependent phase of eiℓϕ where ϕ is the azimuthal coordinate and ℓ is an integer. Because the OAM modes comprise a complete orthonormal basis, they can be used to implement high-dimensional QKD protocols19.

The channels most often used to transmit quantum information are fibre and free-space. Optical fibre has the advantage of being a well-developed optical technology with infrastructure that has been built up alongside the increasing reliance on high-speed internet connection. However, in the case of quantum communication, the significant attenuation losses that come with optical fibres creates a fundamental limit on the distance achievable by QKD protocols. This is because quantum signals cannot be amplified in the same way as classical signals; a consequence of quantum no-cloning theorem20. In addition, fibre-based solutions rely on an established network, increasing the implementation costs of near-term quantum systems. Despite the significance of fibre-based networks for QKD, it is critical to develop and improve on free-space links for ground-to-ground and ground-to-space quantum communication21,22,23. Space-based quantum communication can help circumvent the distance-rate trade-off due to exponential loss in fibre-based networks. The successful implementation of QKD over free-space channels depends on the accurate transmission and detection of single photons after propagation through the atmosphere. Rapid changes in the temperature and pressure of the atmosphere result in variations of the refractive index of the air, creating atmospheric turbulence, which distorts the beam upon propagation24. This spatially distributed non-uniform propagation medium induces continuously varying phase aberrations along the optical path of the communication link. It has been shown in previous works that a turbulent environment has a considerable impact, substantially degrading the quantum state, which results in significant errors within the communication channel25,26,27,28,29. Consequently, the information encoded within the structure of the photons is likely to be lost due to unintended changes in that structure introduced in propagation. In order to implement a realistic high-dimensional free-space QKD system, the system will require compensation for atmospheric turbulence in the channel. One method of correcting distortions in the atmosphere, which is of particular interest, is adaptive optics (AO). While AO has been employed successfully to correct real-time astronomical observations for decades30,31,32, its potential application for free-space communications has only recently been explored33,34,35. In free-space QKD, the use of adaptive optics has been mainly explored theoretically36,37, while experiments antecedent to this work have not demonstrated a significant improvement of the error rate38.

In this article, we demonstrate the use of a fast AO system to correct atmospheric disturbances in a free-space quantum key distribution channel when the information is encoded in the photon spatial modes, namely structured photons. First, we show the improved detector coupling efficiency that our AO system is capable of when used to correct the effects of turbulence on a simple Gaussian beam. We then perform quantum process tomography for dimensions two through five under turbulent conditions, both with and without AO active. We calculate the quantum dit error rate (QDER) of the system for even dimensions from 2 through 10 under turbulent conditions, with both AO on and off. We demonstrate a significant improvement in the error rate of the quantum protocol for all dimensions, even in a robust turbulence regime, which results in high crosstalk (high error rates) among the OAM states without AO.

Results and Discussion

Adaptive Optics in the detection stage

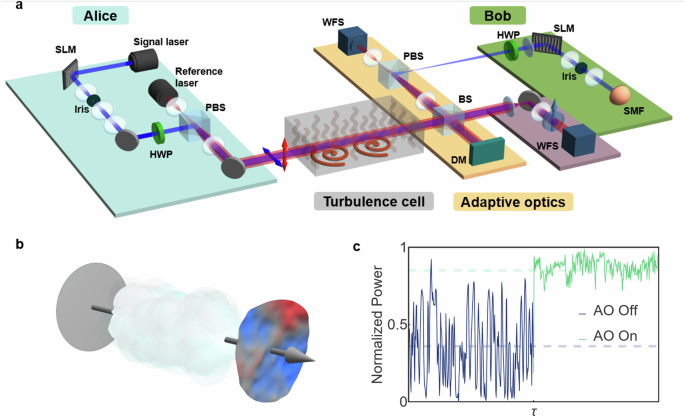

Let us consider that a free-space channel between Alice and Bob has been deployed, allowing them to exchange information encoded using structured light beams. While propagating, the wavefront is distorted due to its interaction with the atmosphere. To compensate for the effects of the optical turbulence, Bob implements a wavefront-correction stage before decoding the message sent by Alice. A scheme of the proposed experimental setup, which uses an adaptive optics system, is depicted in Fig. 1a. To take full advantage of the AO system, Alice and Bob use two co-linear (co-propagating) light beams at the same frequency with orthogonal polarisation states. The first component, a classical signal referred to as the reference beam, possesses a Gaussian profile, which has been expanded to approximate a flat wavefront that completely covers our deformable mirror, and also completely overlaps spatially with the second beam, i.e. signal beam. This allows us to measure and correct the phase distortions within the channel, either from the optical elements or the environment. The second light beam, the signal beam, serves as our information carrier, where the message is encoded by tailoring its complex amplitude using a spatial light modulator (SLM). The signal beam in a true implementation of QKD would be required to be single photons. To benchmark the AO performance is however sufficient to use a classical laser source (an He-Ne laser in our case) since the effects on the spatial modes and the detection technique are the same in the case of a coherent or a single photon state. It must be noted that since both beams share the optical path, they are subjected to the same atmospheric variations and, therefore, both experience the same distortions. Bob is then capable of correcting the distortion on the signal beam using the phase information obtained from the reference beam. For further details of our particular AO system, refer to the Methods section.

a Experimental setup used to investigate the corrective action of a fast adaptive optics (AO) system (from ALPAO49) on structured optical beams after propagation through a turbulent channel. A 633 nm laser impinges on a spatial light modulator (SLM), tailoring the complex field (both amplitude and phase) of the input beam. The polarization of this beam is controlled by a half-wave plate (HWP). Additionally, a second laser source of the same wavelength emits vertically polarized light, which is expanded to approximate a plane wave for use as a reference beam. These beams are combined at a polarizing beam splitter (PBS) and sent through a turbulent cell. Here, the turbulence is generated by employing a controllable hotplate placed inside a glass tank with a width of 30 cm. The composite beam is split using a 50:50 beam splitter; one part goes to a wavefront sensor (WFS) to record the output wavefront, while the second part is fed to the AO section of the experiment. Our AO apparatus consists of a deformable mirror (DM), and a WFS connected in a closed-loop control system. As the WFS measures the structure of the wavefront, the DM changes shape to compensate for the distortions introduced by the turbulence. In our particular experiment, the reference and signal beam are split using a PBS following the corrections applied by DM. Finally, the signal component is sent to a second SLM that performs a projective measurement of spatial modes onto a single-mode fibre (SMF) to determine the probability of detection. b Illustration of the effects on the phase of a plane wave after propagating through a turbulent medium. The colours on the output represent the leading and lagging deformations on the wavefront due to the non-uniform refractive index of the medium. c Normalized optical power coupled into a single-mode fibre, as measured by a power meter during the application of turbulence on a Gaussian input beam. The wavefront correction component is activated ten seconds after the beginning of the measurement. A measurement over a longer time interval is depicted in the Figure S2.

As a first step, our signal takes the form of a Gaussian beam. In the presence of optical turbulence and the absence of a correction mechanism, the coupling of the signal to a single-mode fibre at the receiver fluctuates with respect to time due to the wavefront distortion (see Fig. 1b). As shown in Fig. 1c, when the AO system is inactive, the measured power presents strong fluctuations due to the influence of the introduced turbulence. These effects lead to an average coupling power into the single mode fibre around 36.6% of the value expected without any turbulence applied. Ten seconds after the beginning of the measurement, the AO system is activated, increasing the average measured power to 87.1% and stabilizing the coupling efficiency. If this channel were to be used for free-space polarisation QKD, implementing AO improves the coupling efficiency and thus would have resulted in a doubling of the secret key rate. From these results, it is possible to observe the promising benefits of including a fast AO system in the detection stage for many kinds of free-space communications.

Process Tomography

We perform quantum process tomography to determine the effect of the turbulent channel on the OAM states up to d=5, i.e., (ell =left{-2,-1,0,1,2right}). The results show that the channel fidelity deteriorates significantly under the presence of turbulence. Quantum process tomography is used to determine the effect of a process on quantum states39. A quantum process ({{{mathcal{E}}}}) can be represented using the process matrix χmn to describe how input states ρin are transformed to output states ρout by

with the Gell-Mann matrices, ({hat{sigma }}_{m}) being the high-dimensional extension of the Pauli matrices and satisfying ({sum }_{m}{hat{sigma }}_{m}^{{{dagger}} }{hat{sigma }}_{m}=hat{1}). We seek to determine the process matrix χmn by making projective measurements in the high-dimensional mutually unbiased bases (MUB). These projection measurements are described by the operators ({{{Pi }}}_{m}^{(alpha )}) where the index α denotes the basis and m denotes the state in that basis. It has been proven that for dimensions d that are prime or the power of a prime number, there exists d+1 MUBs40. Thus, in the dimensions explored here, d = {2,3,4,5}, it is convenient to use the MUB approach to perform process tomography. For an arbitrary dimension, symmetric, informationally complete, positive operator-valued measures (SIC-POVMs) can be used to perform process tomography. The MUB measurement operators in dimension d satisfy

respectively for the operators of the same basis and different basis, i.e., α ≠ β. Quantum process tomography using MUBs is described in detail in ref. 41.

The channel fidelity for OAM-based QKD without applied turbulence remains high. As the next step, turbulence is applied, and the state tomography is repeated for each dimension. Without any applied turbulence in the channel, in all dimensions, the channel fidelity remains above ({{{{mathcal{F}}}}}_{p}ge 0.95). After applying turbulence to the channel and repeating the tomography, the fidelity of the channel is reduced as low as ({{{{mathcal{F}}}}}_{p}le 0.45), indicating a high crosstalk among the modes. The state tomography is repeated with AO enabled in both a turbulent and still environment. The results for the process tomography for d = 3 are shown in Fig. 2. In the case of d = 3, we find that the fidelity of the state is maintained such that ({{{{mathcal{F}}}}}_{p}ge 0.98) both with and without turbulence when using adaptive optics. The fidelities of the turbulent channel for all measured dimensions are shown in Fig. 3. Further process matrices can be found in the Figure S4.

The real part of the process matrix of the channel transmission is shown for dimension 3 (a), and dimension 5 (b) both with and without the AO system active when going through the turbulent cell. We perform the process tomography using mutually unbiased bases measurements following the methods outlined in ref. 41 (see Supplementary Note 2). With AO active, fidelity is maintained over 99% in all cases except for that of dimension 5 (lower right process matrix), where the fidelity falls to 98%. Here, we see that the effect of the turbulence on the channel is a complete “channel depolarizing” of the OAM states, i.e., the existence of huge crosstalk, which is successfully undone with the adaptive optics enabled. The process matrices for dimensions 2, and 4 are provided in the Figure S4.

The process fidelity between the tomographically measured turbulent channel with adaptive optics (AO) off (blue) and AO on (green) are measured for a QKD channel of d = 2, d = 3, d = 4 and d = 5. Turbulence `depolarizes’ the channel significantly, i.e. introduces huge crosstalk, while activating a fast AO system compensates for the turbulence effects and recovers the encoded states. Due to the long time required to perform these measurements in higher dimensions, the data for d = 5 was taken on a different day with minor changes to the alignment. This is the main reason why the fidelity for d = 5 is higher than for d = 3, 4, which were taken one after the other. The error bars are obtained by running the maximum-likelihood calculation 10 times, where in each run the average data are modified by a uniformly distributed random quantity contained within the standard deviation of the collected measurements.

Quantum Dit Error Rate and Crosstalk Matrices

To successfully generate a secure key using QKD, it is essential for Bob to accurately detect the state generated by Alice when they choose to operate on the same basis. Any incorrectly detected states will result in a discrepancy between Alice’s and Bob’s keys, which is quantified as the quantum dit error rate (QDER) Q. It must be noted that the maximum value for QDER that is tolerable increases with the dimensionality of the key distribution protocol5,6. In the case of d-dimensional BB84 protocol, the number of bits of secret key established per sifted photon R is given by ref. 42,

where Q is the quantum dit error rate and ({h}_{d}(x)=-x{log }_{2}(x/(d-1))-(1-x){log }_{2}(1-x)) is the Shannon entropy. From Eq. (3), it is possible to find the QDER threshold when R = 0.

Here, the quantum communication channel makes use of two MUB based on two sets of structured beams. The first one, which we consider the logical basis ({leftvert {psi }_{ell }rightrangle }), is given by the family of OAM states with topological charge ℓ, where ℓ is an integer number. To reduce crosstalk, we consider all values of ℓ = − d/2…d/2, excluding the value of ℓ = 0. Meanwhile, the second MUB, known as the angular mode basis (ANG), consists of a set of beams that are a balanced superposition of such OAM modes given by a quantum Fourier transform of the OAM modes.

where j = d/2 + (ℓ − 1) Θ(ℓ) + ℓ Θ( − ℓ), and Θ(x) is the Heaviside function.

In order to obtain the QDER of a turbulent free-space channel, we need to calculate the crosstalk matrix. A crosstalk matrix is determined by sending each of the states in both bases (left{leftvert {psi }_{i}rightrangle right}) and (left{leftvert {varphi }_{j}rightrangle right}), and performing projective measurements of the same states. Based on the properties of MUB, it must be noted that a measurement of a projection made on the incorrect basis, i.e. ({leftvert leftlangle {psi }_{i}leftvert right.{varphi }_{j}rightrangle rightvert }^{2}), is equally likely to result in any of the states of the projection basis with a probability of 1/d. We perform the projective measurements for all even dimensions up to 10, i.e., d = {2, 4, 6, 8, 10}. The experimental crosstalk matrices in dimensions d = 4, d = 6, and d = 10 for both MUBs in our turbulent channel are shown in panels a, b, and c of Fig. 4, respectively.

The probability of detection on each basis for both bases, orbital angular momentum (OAM) modes in the top rows, angular modes (ANG) as defined in equation (4) on the bottom rows, when going through a turbulent channel for a d = 4, b d = 6, and c d = 10. d Plot of the quantum dit error rate (QDER) as calculated from the probability of detection matrices for the cases of adaptive optics on (AO on) and adaptive optics off (AO off) with turbulence active. Here the basis formed by the OAM modes is designated mutually unbiased basis (MUB) 1, while the basis formed by the angular modes is designated MUB 2. The dashed gray boundary line separates the region for which the theoretical threshold value for QDER allows for a secure key to be established between Alice and Bob. While the turbulent channel prevents communication for any dimension greater than d = 2 when the correction system is not considered, Bob’s use of AO allows for secure keys to be established for all cases less than d = 10. Errors bars in panel d are calculated as the standard deviation of the diagonal elements of each associated crosstalk matrix.

Following these results, we proceed to calculate the QDER of our turbulent channel. Fig. 4d depicts the QDER as calculated in each dimension d. The results show that the QDER exceeds the security boundary given by equation (3) in all dimensions where d > 2, measured when no compensation is applied in Bob’s detection stage. Therefore, it is not possible to establish a secure communication channel in the presence of applied turbulence. Nevertheless, when the AO system is active, the QDER is reduced to values below the theoretical threshold for positive key rates in all tested cases except for that of the 10-dimensional ANG basis, while. We find that the average decrease in QDER over all tested cases is 32.5%. This is a promising result, indicating that the use of an AO system can allow for significant improvements in the detection of high-dimensional spatial modes for use in free-space communication.

Utilising Eq. (3), we calculate the sifted key rate that can be achieved after the implementation of AO in our channel shown in Table 1. We show the key rate in a BB84 protocol using a 50/50 balance of each basis, however it must be noted that one can use a weighted protocol in which the logical basis is utilized nearly all of the time allowing for more efficient secret key exchange43.

Our measurements of QDER for different QKD dimensions are shown in Fig. 4d. Interestingly, our results show that the logical basis is more influenced by the introduced turbulence than the ANG basis and the AO performs better on reducing the crosstalk in the logical basis rather than in the ANG basis (this is particularly evident for d = 10). These effects can be qualitatively understood when considering that both (mild) turbulence and adaptive optics mainly affect the phase of the beam. The orthogonality of OAM modes depends on their azimuthal phase structure, so is extremely sensitive to phase distortions, while ANG modes have a smooth phase dependence but different intensity distributions. The AO performs less well on ANG modes in higher dimensional basis since these modes are increasingly localised in the azimuthal coordinate, thus a higher resolution is needed to compensate for the aberrations induced by turbulence.

Our experiment demonstrates that the use of a sufficiently advanced adaptive optics system can allow for high-dimensional quantum communications in channels where turbulence would otherwise prevent it.

Turbulence Measurement

In our experiment, a second WFS is used in our setup in such a way as to monitor the reference beam before the correction of the DM was applied (see Fig. 1a). From the collected data, it is possible to extract instantaneous wavefronts and the corresponding decomposition in terms of Zernike polynomials as functions of time. In Fig. 5, we show standard deviations of the first nine Zernike coefficients, excluding the first one, a global phase shift, over a period of 195 seconds with active turbulence. The strength of the fluctuations in our experiment is in the range of those measured in a previous experiment, where a 3m underwater channel was characterized17. In this experiment, a secure key could not be generated when d = 4 due to the effects of the underwater turbulence. In our experiment, we also find that a secure key cannot be generated for d = 4 unless wavefront correction using a fast AO is implemented in the channel. Thus, our results are promising not only for free-space applications but also for other turbulent environments, i.e. underwater channels.

Standard deviation of the first nine coefficients aj of the Zernike decomposition after propagation through the turbulent cell. The Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor reports the turbulence decomposition in the Zernike polynomials basis as a function of time. The inset depicts an aberrated wavefront at a particular time t0, where w0 is the beam waist of the Gaussian mode that would be included in the protocol if using odd dimensions.

In addition to measuring the Zernike coefficients, we calculate the Fried parameter r044,45,46. This parameter represents the average diameter of the theoretical circular air pockets across which the wavefront phase experiences one radian of variation. From the Fried parameter, we can quantify the strength of the turbulence introduced in our system with the parameter D/r0, where D represents the diameter of the effective aperture used to estimate r0. In our experiment, we obtained r0 by measuring the beam wander of a Gaussian state sent through the channel over time44. Here, D is given by the waist of the Gaussian beam considered. Following this, we find that the turbulence used in our experiments has a value of D/r0 = 1.70. This value indicates that our turbulent cell generates moderate turbulence38. This allows us to compare with previous attempts to use active compensation to increase the key rate. Previous studies showed that under similar turbulence conditions, the improvement in QDER when using AO was not enough to establish a secure channel when d = 538. This impossibility is likely to have resulted from the implementation of an AO system that uses only 9 actuators in comparison to the 97 actuators used in this work.

Conclusion

In this work, we have tested the capabilities of a fast and high-resolution adaptive optics system in the context of free-space communication channels. We have shown that AO can significantly improve the coupling of a Gaussian beam propagating through a non-uniform, changing medium, showing a potential doubling of the resultant key rate for polarization, or time-bin QKD where the Gaussian most likely used mode. Then, we demonstrated the advantage of the use of AO in performing high-dimensional quantum key distribution using spatial modes of photons. Through process tomography, it is shown that the inclusion of the compensation increases fidelity with the identity matrix from under 50% to over 95% in dimensions up to d = 5. Finally, we demonstrate that by utilizing AO, it is possible to implement a high-dimensional BB84 QKD protocol through a turbulent channel, where it would otherwise not have been possible. We note that the observed turbulence is similar to previously performed experiments both indoors and underwater, as confirmed by Zernike decomposition and the estimation of the Fried parameter. We also expect that, in situations where AO alone is not sufficient to recover the secure key rate, it can nevertheless offer an invaluable aid in reducing the effective turbulence strength providing support to more advanced methods of real-time process tomography47. We foresee using an AO system in practical free-space links for classical and quantum communications, in particular, in QKD networks utilizing satellites.

Methods

Adaptive optics system

The AO system used in our experiment is manufactured by ALPAO and consists of three main components: a deformable mirror (DM) a Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor (WFS), as well as a feedback-control system. The DM in our configuration (DM9725) has a diameter of 22.5 mm, and utilizes 97 electromagnetic pistons behind the reflective surface in order to modify its profile. These pistons are organized in an 11 × 11 grid pattern with cut corners to conform to the circular shape of the mirror. It has a settling time of 1.5 ms, and can therefore operate optimally up to and even slightly above 600 Hz. On the other hand, the Shack-Hartmannn WFS (SH-EMCCD) has an array of 16 × 16 microlenses in order to correctly measure the reference beam wavefront. It operates at a frequency of 1kHz. The correction calculations are performed by ALPAO Real Time Computer (RTC) and the interface with the whole system is given by using ALPAO Core Engine (ACE) in MATLAB version R2019a Update 3. The system is dependent on the operating frequency to be faster than that of the Greenwood frequency, fG. This frequency is the rate at which the turbulence structure within the optical path changes form48. We can then consider 1/fG = τG to be the Greenwood time constant which is the amount of time that the turbulence structure is constant. During the experiments, the AO system was operating at 200 Hz. While we do not measure the Greenwood frequency of the turbulence generated in the lab, we can be sure that it is less than 200 Hz as the AO system operated without issue.

Turbulent cell

In our experiment, the turbulence cell consists of a hotplate contained within a glass-walled water tank. In it, the variations of the refractive index are produced by the temperature gradient generated by the hotplate. As the layer of air close to the plate gets hotter, it rises and displaces the colder layers of air, allowing to generate isolated turbulence inside the tank along a path of 70 cm. The strength of the effective turbulence can be controlled by setting the hotplate at different temperatures. As shown in Figure S3, as the temperature of the hotplate is increased, the standard deviation of the coefficients aj of the Zernike decomposition also increases. All experiments were performed with the hotplate setting 1 shown in Figure S3.

Responses