Biallelic variants in RYR1 and STAC3 are predominant causes of King-Denborough Syndrome in an African cohort

Introduction

King-Denborough syndrome (KDS, OMIM 619542) is a rare form of neuromuscular disorders, more specifically, congenital myopathy (CM) [1, 2]. The clinical spectrum of CM is broad and is typically diagnosed clinically (after extensive neurological evaluations) in neonates presenting with generalised hypotonia, muscle weakness, facial weakness, respiratory insufficiency, and feeding difficulties [3,4,5,6]. More specifically, in KDS, patients are characterised by myopathic and facial dysmorphia, musculoskeletal abnormalities, and susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia (MH) [1, 7, 8]. Furthermore, in addition to clinical diagnosis, a comprehensive, precise diagnosis often depends on biochemical evaluations such as muscle imaging, muscle biopsy, and comprehensive genetic testing. Identifying a genetic cause in a patient with a suspected inherited KDS requires access to genetic testing and expert evaluation of results, considering neurological/muscular clinical features, age of onset, inheritance patterns, and population-specific trends. The aetiology of KDS in African patients is largely unknown; however, it has been reported in other populations to have an underlying genetic cause due to autosomal dominant mutations in the RYR1 gene [2, 9]. Research conducted in South Africa has identified common genetic autosomal recessive inherited RYR1 mutations [(c.5726_5727delAG (exon 35), c.6175_6187del (exon 38), c.8342_8343delTA (exon 53), c.14524G>A (exon101), and c.10348-6C>G (intron 68)] in patients with CM characterised by central nuclei myopathy, with no clinical characteristics of KDS [10]. The presence of STAC3 pathogenic c.815G>C; p.Trp284Ser homozygous variant has been reported in other groups with African ancestry [11, 12], and in 2024, a South African study confirmed homozygous STAC3:c.851C>G in 25 out of 127 (20%) participants presenting with congenital hypotonia [13]. Prior to this, we identified the first homozygous STAC3:c.851G>C variant in a Black African female patient as part of a study investigating the potential nuclear genetic background of patients with biochemically confirmed mitochondrial disorders [14].

Our paediatric neurology clinic at Steve Biko Academic Hospital (SBAH) in Pretoria, provides tertiary care services, primarily serving the northern regions of South Africa. Over the past 25 years, we have observed a subset of patients with CM who present with clinical and phenotypic features strikingly similar to those of KDS. These patients exhibit a range of KDS characteristics, including myopathy, ptosis, malar hypoplasia, skeletal and other dysmorphic features, cryptorchidism, and, in some cases, documented episodes of MH following surgery. The recurring presence of these prominent features strongly suggests a shared underlying genetic aetiology in this patient cohort with a KDS-like phenotype.

In this study, we used whole exome sequencing (WES)—accessed through the International Centre for Genomic Medicine in Neuromuscular Diseases (ICGNMD)—to investigate a cohort of 67 South African participants in the ICGNMD study with neuromuscular diseases of suspected genetic origin. We identified a genetic diagnosis for 54 CM participants (~81%), 44 of which presented with KDS-like features. Notably, all participants with KDS-like features were found to carry biallelic variants in the RYR1 and STAC3 genes, with the latter representing a novel genetic association with KDS. These findings highlight the importance of RYR1 and STAC3 as common genetic causes of neuromuscular diseases in African patients. Our results advocate for routine screening of these genes in patients presenting with KDS-like features to improve diagnosis and treatment.

Patients and methods

Study recruitment and inclusion/exclusion criteria

Ethical clearance was granted (Approval Numbers: 296/2019 from the University of Pretoria and NWU-00966-19-A1 from the North-West University) to recruit patients with a suspected inherited NMD as well as their affected or unaffected relatives for clinical and genetic analyses. Three central hospitals in Gauteng provide specialised services for NMD. There are ~8 million children between 0 and 14 years of age in Gauteng and the four neighbouring provinces (https://www.statssa.gov.za/ last accessed June 2024). Although there is a slight overlap in the referral areas of the three facilities, Steve Biko Academic Hospital (SBAH) predominantly provides services to the northern municipal regions in Gauteng, as well as the Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces with a paediatric population of approximately 4 million between the ages of 0 and 14 years. The recruitment site manages the entire spectrum of paediatric neurology and neurodevelopmental disorders, with an average of 6500 patients per annum.

All individuals with a clinical phenotype compatible with NMD of a suspected genetic origin were eligible for inclusion in the broader ICGNMD project. Here, we report on the subset of participants with onset of symptoms at birth or within the first six months of life (the congenital group) and with completed genetic analysis (WES, if initial local investigations did not confirm a diagnosis). In addition, participants with muscle weakness not explained by known phenotypes as described in the exclusion criteria were also included.

Exclusion criteria comprised incomplete genetic information and patients with a prior diagnosis of Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy, metabolic myopathy, spinal muscular atrophy or other syndromes associated with neonatal hypotonia and/or muscle weakness.

Between October 2020 and February 2024, 255 probands and 377 family members (23 clinically affected) gave informed consent to participate in the ICGNMD study. Participants were mainly recruited from the northern provinces of South Africa (Fig. 1A–C).

A Geographical distributions of first or home languages in South Africa, illustrating linguistic diversity in the northern provinces: Limpopo, Mpumalanga, Gauteng, and North-West Province. B Pie charts showing the distribution of the 67 study participants according to their primary language, broken down by referring province. C Language group distribution of 44 KDS-like participants (with RYR1 and STAC3 mutations), categorised by major language groups: Nguni-Tsonga or Sotho-Tswana.

To assess the ethno-linguistic influence on the disease patterns, the ethnicity, language group, self-reported language, and province of origin were collected. There are nine provinces, 12 official languages, and four major population groups in South Africa. The latter are officially referred to as Black African, Coloured/mixed, Asian/Indian, and White.

The nine major African languages originally stem from the Niger-Congo family. Within this family, the Southern Bantu-Makua group is divided into the Nguni-Tsonga and Sotho-Makua-Venda groups, which are further subdivided into the Sotho-Tswana and Tshivenda groups. These ethno-linguistic groups are spread across the country, with different languages dominating various provinces.

Participant assessment and data collection

A thorough clinical assessment was conducted for all probands and affected relatives. Pseudonymised participant data were entered into the ICGNMD-REDCap Study Database, which includes the family history, relevant medical and surgical history, clinical findings, and results of available prior investigations. Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms were used to summarise the key clinical features for maximum interoperability (https://hpo.jax.org/app/). Demographic details and medical histories were documented, including pedigrees (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Participant sample collection

Whole blood samples (5 ml) from consenting participants were collected and stored (−80 °C) according to standard procedure until DNA extraction was performed using the FlexiGene® DNA Kit (51206; Qiagen Science, Hilden, Germany).

Genetic testing and whole-exome sequencing (WES) data analysis

All participants, except two with locally confirmed diagnoses, underwent WES according to the protocol described by Wilson et al. [15]. The relevant CM and CD panels (Genomics England PanelApp, v.4.38 and v.4.24, https://panelapp.genomicsengland.co.uk, last accessed July 2024) were applied. Variants of interest were classified according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines [16]. Potential disease-causing variants were validated and examined for segregation via familial Sanger sequencing at the North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa. Sanger data were analysed using GEAR-Genomics (https://www.gear-genomics.com, last accessed June 2024) [17].

STAC3-variant haplotyping

To assess the homozygosity and potential for founder effects within the region of the STAC3:c.851G>C variant, a subset of 26 samples was analysed according to the protocol described in Bisschoff et al. [18]. Analysis was hampered by the under-representation of Black South African sub-population allele frequency data in linkage disequilibrium and Maximum Allele Frequency data in publicly available datasets, with the “geographically/genetically closest” but distant, being that of the ‘Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria’ population data from the 1000 Genomes Project. RYR1 haplotyping was previously documented for the local population from the southern regions of South Africa by Wilmshurst et al. [10].

Population analysis and frequency determination for the STAC3:c.851G>C variant

Ethics approval (NWU-00966-19-A1) included population-based screening for the most common variant detected in the cohort, STAC3(NM_145064.3):c.851G>C, using PCR-RFLP analysis. DBS cards, collected between 2020 and 2022 from healthy newborns of parents from the northern provinces and belonging to the four largest population groups in South Africa, were used as a DNA source. The gender distribution of the samples was equal, and all samples were anonymised and randomised, with 750 available for each ethnicity apart from the Coloured/mixed group, where only 594 samples could be sourced. The DBS cards were collected for routine metabolic testing (not due to suspicion of a metabolic disorder) and were considered representative of the local populations.

Briefly, DNA was amplified directly from the DBS cards Phire HS II Master Mix (F170L, Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) and the following primers: Forward 5′-TTA ATG GTT AAG CTC TCC AAG GAG TGT-3′, Reverse 5′-GTA CTG CGG AGT GAA GAG GAA AGA-3′. The region spanning the STAC3:c.851G>C variant was then digested by the restriction enzyme TfiI (R0546S, New England Biolabs, Massachusetts, USA), which recognises and cuts the variant sequence (5′-G^AWTC-3′). Frequencies were calculated and stratified by broad-reported ethnic group using the formula:

Where p represents the allele frequency of the variant, AA is the ratio of homozygous affected samples per total number of samples per population group, and AB is the ratio of heterozygous samples per total number of samples per population group.

The STAC3 frequency was then compared to other population groups listed in gnomAD [African/African American and European (Non-Finnish), v4.1.0, https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/ last accessed July 2024] and the Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) project (African, Caucasian and Coloured/mixed) https://agvd-dev.h3abionet.org, last accessed July 2024).

Results

Demographics

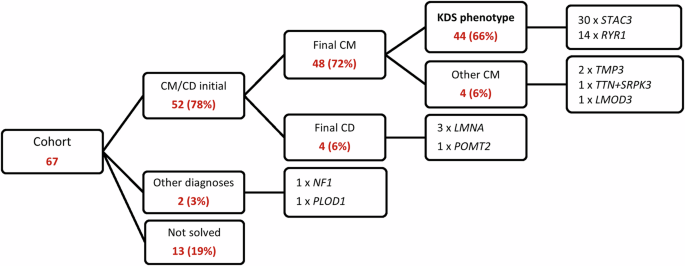

Figure 1A–C summarises the geographic and ethno-linguistic distribution of the KDS cohort in South Africa. The majority of participants, 56 (84%), came from our direct referral areas, which include Northern Gauteng and the Limpopo, and Mpumalanga provinces. The remaining 11 (16%) were referred to our clinic for specialised opinions and diagnostic purposes. Sixty-seven participants with a broad clinical phenotype of CM/CD met the sub-study inclusion criteria. The overall outcomes of the entire cohort are shown in Fig. 2. Following WES analysis, the genetic diagnosis of 13 (19%) participants remained unsolved. Alternative diagnoses of Neurofibromatosis (NF1-variant) and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (PLOD1-variant) were identified in two participants. Out of the 52 remaining participants, four had a final diagnosis of CD and 48 of CM. Four of the 48 CM participants had a genetic diagnosis other than STAC3– or RYR1-variants, while the remaining 44 participants, all displaying the clinical features suggestive of KDS, carried either STAC3- or RYR1-variants.

Summary of the overall phenotypic and genetic findings for the original neuromuscular disease cohort of 67 participants.

Clinical and biochemistry findings

The distinctive clinical features of the 52 participants with CM/CD phenotype are shown in Table S1 and Fig. 3. As expected, the outstanding difference between the genetically diagnosed CD and CM groups was the markedly higher CK values observed for the former (mean value 2060 IU/L vs 96 IU/L, p < 0.001). In the CM group, three of the four participants (75%) with a genetic diagnosis other than RYR1 or STAC3 had marked neck flexor weakness. This was not recorded in any of the KDS-like participants. The 44 participants make up the KDS-like cohort are described in greater detail below.

Comparison of the most prominent clinical features, based on the three King-Denborough syndrome classifications, for the RYR1 and STAC3 genotypes in participants with KDS. All values are expressed as percentages.

Included families

The group spanned 42 families and included 23 males and 21 females. Eighteen (40%) participants had a history of affected siblings, two of whom were included in the study. The pedigrees and relevant segregation analyses are summarised in Fig. S1.

Perinatal history

Twenty-five (57%) participants were reported to have experienced decreased foetal movement, and five (11%) were in breech presentation. All participants were floppy at birth, with only 4 (9%) not experiencing feeding difficulties. Respiratory difficulties were reported in 22 (50%) babies, although none required ventilatory support during the neonatal period.

Myopathy

All participants exhibited hypotonia, generalised muscle weakness, and facial weakness (myopathic facies) since birth. The facial weakness aligned with the description of Webb et al. [19] and associated with an expressionless face, absence of nasolabial and periorbital folds, incomplete eyelid closure, open triangular mouth, and drooling. Older participants also exhibited articulation difficulties and peri-oral weakness [19].

Dysmorphic features

Eye abnormalities were documented in 26 (59%) participants. Bilateral ptosis was present in approximately half of the participants in each group: 7 (50%) in the RYR1 group and 16 (53%) in the STAC3 group. External ophthalmoplegia was observed in 9 (64%) of the RYR1 group but only in 5 (17%) of the STAC3 group. A high prevalence of external ophthalmoplegia was also reported in another South African cohort with RYR1 variants, as noted by Wilmshurts et al. [10].

All participants had palatal abnormalities. In the STAC3 group, the majority, (19 or 63%) had cleft palates, while the remaining 11 (37%) had high, narrow palates. All 14 (100%) participants in the RYR1 group had high, narrow palates.

Although neck abnormalities are documented in KDS [2], they were not prevalent in our cohort. Only three (10%) participants in the STAC3 group exhibited short necks based on clinical assessment. In the STAC3 group, 22 (50%) presented with talipes equinovarus, nine (30%) with camptodactyly and six (20%) with cryptorchidism. None of these phenotypes was observed in the RYR1 group. Joint hypermobility was present in 22 (50%) KDS-like participants. Multiple contractures were more evident in the RYR1 group [4 (29%)] than in the STAC3 group [4 (13%)]. Pectus carinatum and kyphoscoliosis were proportionally more prevalent in the STAC3 group [15 (50%) and 20 (67%)] compared to the RYR1 group [1 (7%) and 4 (29%)]. Interestingly, short stature was more prominent in the STAC3 group [21 (70%)], whilst only reported in 4 (29%) participants in the RYR1 group. It should be noted that the severity of spinal deformities, such as kyphoscoliosis, can affect the accuracy of height measurements.

Malignant hyperthermia susceptibility (MHS)

Reliable data on MH are challenging to collect since this is only expected to develop upon administration of volatile anaesthetic gasses (isoflurane) or succinylcholine [20]. The in vitro contracture test has excellent specificity and sensitivity to detect MHS, but is not routinely available nor is it available at our facility [6]. When surgical intervention is necessary for a patient with a CM (e.g., to correct a cleft palate), preventative protocols can be implemented to ameliorate the risk of MH. Eighteen (41%) participants had undergone surgery. Among this subset, MH was observed in eight (18%) participants from the STAC3 group. An additional 10 (33%) participants in the STAC3 group underwent surgery with precautionary measures for MHS in place, resulting in an uneventful intra-operative course. None of the participants in the RYR1 group were exposed to anaesthetics during the period of data collection. Therefore, MHS status, remains unknown for 26 (59%) participants in the entire KDS group.

Other clinical associations

All 44 participants had areflexia. Four (13%) participants had conductive hearing impairment in the STAC3 group.

Genetic findings

As summarised in Table 1, all 44 KDS-like cohort participants were found to have either biallelic STAC3 or biallelic RYR1 variants as the likely cause of their CM. No CACNA1S variants were detected by WES. Details concerning the other genetic variants identified in the larger CM cohort, are also provided in Table 1.

RYR1 variants

None of the 44 participants exhibited an AD inheritance pattern as initially described for KDS-associated RYR1 variants [2, 8, 21]. A total of 14 (32%) participants were found to have compound heterozygous RYR1 variants, with the majority [13 (93%)] harbouring the known African RYR1 common allelic combination, RYR1(NM_000540.3):c.[10348-6C>G;14524G>A], combined with a splice-altering, in-frame deletion and/or frameshift variant.

STAC3 variants

Thirty of the 44 participants (68%) carried the pathogenic missense variant, STAC3(NM_145064.3):c.851G>C. Among these, 27 (90%) were homozygous for the variant, while three (10%) were compound heterozygous, carrying both the STAC3:c.851G>C variant and the novel heterozygous deletion, STAC3(NM_145064.3):c.834_836del.

Cohort comparison of previous studies with RYR1 and STAC3 genotypes

The clinical features of the 44 participants were compared to previously published cohorts (Table 2 and 3), three with RYR1 genotypes and three cohorts with STAC3 genotype [2, 9,10,11, 13, 22]. The most common features observed in our cohort were consistent with CM, including hypotonia (100%), muscle weakness (100%), and respiratory symptoms (100%). Notably, cleft palate (40%), talipes equinovarus (50%), and cryptorchidism (16%) were frequently observed, with a higher incidence than in some other cohorts, reinforcing the unique phenotypic characteristics of KDS-like presentations in African patients.

Haplotype for RYR1 and STAC3 in South Africa

The WES results confirmed the frequent presence of the RYR1 haplotype, c.[10348-6C>G;14524G>A], as described by Wilmshurst et al. [10]. The haplotype data for the STAC3:c.851G>C, expands on that reported by Essop et al. [13]. We analysed a subset of 26 samples harbouring the homozygous STAC3:c.851G>C variant. The results revealed varying lengths of regions of homozygosity, with a minimal shared region of 0.39 Mb, indicating the presence of the same haplotype on both alleles (Fig. 4). These findings suggest the potential emergence of a founder haplotype associated with this STAC3 variant. However, due to lack of sufficient control data from the same population, accurately estimating the haplotype frequency remains challenging. Additionally, an examination of the Black African data within the 1000 Genomes Project revealed a limited number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the reported region. These SNPs are characterised by a high heterozygosity rate and low linkage disequilibrium, which further complicates haplotype analysis.

Genotype analysis for a subset of 20 carriers of STAC3:c.851G>C.

Allele frequency for STAC3 in South Africa

The allele frequency analysis of 750 healthy DBS samples collected from northern South African provinces for the STAC3:c.851G>C variant, revealed a carrier rate of 0.13%. This equates to a disease prevalence of 17.8 cases per 100,000 live births. To validate this finding, we assessed the allele frequency for STAC3:c.851G>C, with population frequencies from the gnomAD database (v.4.1, last accessed June 2024), as detailed in Table S2. Importantly, no homozygotes for c.851G>C variant have been identified in the gnomAD population database across any of the listed populations.

Discussion

The ICGNMD study recruited 632 participants, of which 255 were probands presenting with a neuromuscular disease phenotype, from the northern provinces of South Africa. Of these, 67 were classified as having CM, characterised by features such as hypotonia, muscle weakness and developmental delay. Further investigations revealed that 44 of these 67 CM patients exhibited specific KDS-like phenotypes, comprising a triad of features that includes myopathic and dysmorphic traits, as well as MHS, suggesting an underlying genetic aetiology. Furthermore, all 44 participants were of African descent, representing the largest KDS-like cohort reported from Africa to date, with only two patients previously described in South Africa [23]. The genetic history of KDS reveals an AD inheritance pattern associated with mutations in the RYR1 gene. In our cohort of 44 KDS-like participants, 14 harboured RYR1 variants with exclusive AR inheritance, while 30 carried a common STAC3 variant, also with AR inheritance, previously associated with congenital myopathy and Bailey-Bloch myopathy [11, 24, 25]. This finding suggests a novel genetic aetiology for KDS in African patients.

Distinct phenotypic differences were observed between the RYR1 and STAC3 groups (Table S1, Fig. 3 and Tables 2 and 3). Features exclusively associated with the STAC3-KDS group included cleft palates, talipes equinovarus, and cryptorchidism (phenotypes observed in KDS).

Additionally, dysmorphic features observed in KDS such as short stature, kyphoscoliosis, and pectus carinatum occurred at a higher frequency in the STAC3 group, whereas ophthalmoparesis and high narrow palates were more frequent in the RYR1 group. Notably, none of the RYR1 participants required surgery during the study period and were classified as having an unknown risk for MH [26].

Furthermore, the phenotypes observed in our cohort align not only with the KDS-like features described in prior studies of RYR1-associated disease for KDS but also with broader CM studies focussing on STAC3-related variants [2, 9,10,11, 13, 22]. These studies consistently reported overlapping features of congenital myopathy, dysmorphic traits, and MHS. Notably, the higher frequency of cleft palate, talipes equinovarus, and cryptorchidism in our cohort underscores the distinctive phenotypic contributions of STAC3 variants to KDS-like presentations. This dual alignment of STAC3 with both congenital myopathy and KDS phenotypes positions it as a novel finding, expanding the genetic framework of KDS. Furthermore, while RYR1 and STAC3 cases from prior studies share many KDS-like features, differences in the prevalence of skeletal dysmorphisms and other traits highlight regional and genetic variability.

The South African haplotype RYR1:c.[10348-6C>G;14524G>A], occurring in cis, was identified in 13 of the 14 (93%) RYR1 group. This haplotype was detected as compound heterozygous with five pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in trans (Table 1). Among these 13 participants (P01-P08), the RYR1:c.8324_8326delTA variant, which lies outside an MH hotspot domain, was also present. This deletion affects the domain responsible for binding to DHPR and activating RyR1. Additionally, two splice acceptor variants were identified: RYR1:c.12625-1G>A (P09), located in MH hotspot domain 3, and RYR1:c.6797-1G>A (siblings P10 and P11), located in MH hotspot domain 2 [26]. Participant P12 carried an intronic splice donor mutation, RYR1:c.2780+1G>T, located one base pair downstream of exon 23. This mutation has the potential to interfere with the splicing process of intron 24. Additionally, a significant eight-base pair insertion was detected between positions c.12814 and c.12815 in participant P13. This insertion occurs within the Ca2+ binding domain of RyR1, which has a strong affinity for Ca2+, and is crucial for activating RyR1. Moreover, this insertion is located within MH domain 3 [26]. Participant P14 had two compound heterozygous variants of uncertain significance (VUS) according to ACMG criteria (Table 1). These variants, RYR1:c.10280C>T and RYR1:c.2682+4A>G, are located outside of the MH hotspot regions. The former is proposed to be situated in an interdomain interaction region, while the latter is a potential splice variant [26]. When evaluating the severe phenotype of P14, a case can be made to reclassify these variants as likely pathogenic, by adding ‘PP4, Patient’s phenotype or family history is highly specific for a disease with a single genetic aetiology’; however, the severity and penetrance could not be determined.

In this study, we report a novel STAC3 deletion, STAC3(NM_145064.3):c.834_836del; p.Asp279del identified in three unrelated CM participants. This three-nucleotide deletion results in the removal of a single amino acid, aspartic acid at position 279. The variant is in a non-repeat region and has an extremely low frequency in the African population according to gnomAD. This deletion was assigned pathogenic moderate (PM) scores, specifically PM4 and PM2. We propose that this variant, in combination with the known pathogenic STAC3:c.851G>C (in trans), likely impacts the functionality of STAC3. These RYR1 and STAC3 variants identified in our African participants, are exceedingly rare in global datasets such as gnomAD. To date, there are no reports of the specific African haplotype (RYR1:c.[10348-6C>G;14524G>A]) being identified in non-African patients. However, phenotypes associated with RYR1 and STAC3 in other populations share significant overlap with those described here, including susceptibility to MH and the triad of KDS features. We suggest that the common STAC3 variant, c.851G>C, previously identified in many non-African populations could have an African founder effect, given the large region of homozygosity observed in our cohort. Our extensive allele frequency analysis, along with findings from other studies [13], supports a high prevalence (0.13%) of the STAC3:c.851G>C variant in the Black African population, especially across the northern provinces of South Africa. Mapping Black African CM participants to ethno-linguistic groups did not reveal significant gene or variant trends within this diverse population. For instance, RYR1 and STAC3-related KDS were present in a 1:2 ratio in both groups (Fig. 1C).

In conclusion, over the last 25 years, patients with CM exhibiting distinctive KDS features, have visited our clinic at Steve Biko Academic Hospital, receiving clinical diagnoses and treatment, but never a genetic confirmation. Through the ICGNMD study initiative [15], we successfully established the genotype–phenotype correlation and provided genetic diagnoses for 44 African KDS-like participants during this study. A genetic diagnosis of STAC3-related disease has critical implications for patient care. Many patients with STAC3-related disease may require surgeries, such as cleft palate repair or correction of clubfoot, during their lifetime. Identifying pathogenic variants in STAC3 can inform anaesthetic management, reducing the risk of MH-related morbidity and mortality. This is particularly significant given the high prevalence of MH in STAC3-KDS participants in this cohort. A genetic diagnosis also allows for preoperative risk stratification and tailored interventions, underscoring the importance of routine genetic screening in patients with suggestive phenotypes [13, 27]. In South Africa, genetic screening and next-generation sequencing options are limited for the average individual. Given the importance of early detection for treatment, as well as the significant risk of MH during corrective surgical procedures, the National Health Laboratory Services has developed a programme to support low-cost, targeted genetic testing for patients with suggestive phenotypes.

Finally, the study affirms that regional cohorts of CM face diagnostic odysseys that can only be addressed by improving access to genomic medicine and increasing discovery research funding. Emphasising comprehensive history taking and thorough clinical examination, combined with extensive knowledge of associated disease phenotypes and genes, can expedite diagnosis, spare patients from unnecessary and potentially painful investigations, and deliver cost savings.

Relatively low-cost diagnostic algorithms for specific disorders can be developed, given a well-characterised population. Utilising pattern recognition and a stepwise approach in the diagnostic process can resolve most cases, saving both time and money. However, a subset of cases will require a multidimensional approach to fully delineate the underlying pathogenomic mechanisms.

Responses