Building collaborative infrastructures for an interdisciplinary higher education master’s program

Introduction and background

We should work to usher in an era when interdisciplinary departments, programs, and centers do not supplant or replace the traditional disciplines but serve instead to create pathways and intersections, bringing faculty and students together for the common endeavor of intellectual exchange. (Kleinberg, 2008 p.11)

For decades, institutionalizing interdisciplinarity in higher education has been an ongoing topic. Scholars such as Augsburg, Holley, Klein, Vienni-Baptista, and Lattuca have explored the difficulties in developing the physical and cultural space for interdisciplinarity on campuses. Despite the growing interest and willingness from students, researchers, and teachers to engage in interdisciplinary work, studies have consistently concluded that institutional and administrative barriers prevent strong institutionalization of interdisciplinary research and education (cf. Lattuca, 2001, p.169; Klein in Holley, 2019). The solutions they proposed were to ensure more stable funding (Klein, 2010), hire tenured staff for interdisciplinary sections (Holley, 2019), and redesign the physical and administrative layout of institutions to better accommodate interdisciplinary collaborations (Klein et al., 1997, Lattuca 2001). Meanwhile, in his paper from 2008 and in the quote above, Kleinberg challenges this approach. While he agrees that the purpose of interdisciplinarity is to create connections and collaboration across disciplines, he warns against over-institutionalizing these efforts. Kleinberg argues that if interdisciplinary programs, centers, and departments become too stable and independent, they risk becoming isolated “fortresses” that disconnect from the broader academic community (Kleinberg, 2008, p.10).

The disagreement on how to sustain interdisciplinary initiatives is interesting, but perhaps also an indication of why we still discuss it. There is no simple solution. Although most discussions and studies focus on how to institutionalize interdisciplinarity, Kleinberg’s perspective inspires us to consider an alternative, which is creating flexible and adaptable pathways and intersections, rather than achieving full institutionalization. In this paper, we explore how such flexible pathways can be built, using the context of a master’s program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) developed by the Interdisciplinary Consortium for Applied Research in Ecology and Evolution (ICARE) as a case study. In this, we also explore the roles of the students (Trainees), the staff, and teachers and a physical tool for interdisciplinary teaching, learning, and collaboration Table 1.

Collaborative infrastructures

Infrastructure typically brings to mind tangible structures like roads, bridges, and trains, but in today’s world, we increasingly rely on intangible infrastructure such as databases and digital platforms (Star, 1999). Similarly, in interdisciplinary collaborations that cut across institutions and physical or digital spaces, it is crucial to develop underlying structures that support ongoing collaboration and dialog. These structures must be flexible enough to adapt to various contexts and capable of addressing power dynamics, enabling adjustments as needed.

Interdisciplinary programs in higher education exemplify this type of collaboration. While some programs are initiated by institutions and lead to organizational restructuring (e.g., at the University of Leuphana in Germany and several UK universities), others are launched by institutional management in partnership with external stakeholders or across institutions (Vienni-Baptista et al., 2024). However, many recent programs have been initiated by individuals within institutions, often with external funding, and are added to existing structures (Szostak, 2024).

Regardless of how these programs originate, integrating them into existing institutional structures is challenging. Changing the institutional layout can disrupt everyday practices for students and staff, while collaborations with external stakeholders may challenge established practices and traditions, leading to frustration and resistance. Bottom-up initiatives, which are often driven by individuals with limited support from management, are particularly difficult to sustain (cf. Vienni-Baptista et al., 2024; Holley, 2019).

Courses and programs that bring together students with diverse backgrounds struggle to align expectations and design a curriculum that accommodates varying academic levels and prior knowledge. Faculty and staff from different disciplines also find it challenging to harmonize their teaching methods and administrative systems. As a result, they may spend more time planning these courses or deprioritize them, since interdisciplinary teaching is often seen as less critical to their careers than core teaching in their respective fields (cf. Foley (2016). These challenges illustrate the importance of building a flexible and intuitive infrastructure for interdisciplinary collaboration, or what could also be defined as a system designed to serve a group with diverse perspectives and needs within a framework originally built for different purposes.

In studying the coherence, connections, and collaboration within ICARE, we have found inspiration in the concept of collaborative infrastructures, and the work of Selloni (2017). Selloni defines a collaborative infrastructure as “a system made up of non-human elements and human actors for making and imagining” (p.134) and as “a set of weak framework conditions for making attempts” (p.137). Based on her studies of public innovation spaces, she identifies a number of characteristics of collaborative infrastructures, such as being formatted (relying on a set of recognizable standards), undetermined (encompassing the notions of flexibility and openness), situated (in connection to specific spatial and temporal dimensions), hybrid (cutting across organizational, sectoral or disciplinary boundaries), modular (as modules to be combined in diverse ways in order to develop various public-interest services), weak (a light, incoherent and fallible infrastructure), and empiric (adding and developing activities along the way) (Selloni, 2017 pp. 136–137).

We are interested in understanding how ICARE functions as a collaborative infrastructure within higher education. Specifically, we examine its formatting (including tools used, strategies adopted, and rules respected), its embeddedness within UMBC and the broader North American higher education system (what Star (1999) calls being “sunk” into existing structures), and its hybrid characteristics that cross organizational boundaries—particularly how ICARE activities integrate with existing master’s programs and involve diverse stakeholders across the university. This investigation is guided by two main research questions:

-

1.

How does the ongoing development and addition of collaborative activities within ICARE affect its strength and effectiveness as an infrastructure while operating across organizational boundaries in the higher education context?

-

2.

More broadly, how can collaborative infrastructures be built and sustained to support interdisciplinary education, and what are their impacts on participants and stakeholders?

Employing collaborative infrastructures as a concept in our analysis of the ICARE program allows us to view coherence, connections and collaboration within ICARE as continuous processes, or ‘infrastructuring,’ that emerge and dissipate through the socio-material practice. This enables us to identify traits that might be specific to ICARE, but also at play in other interdisciplinary study programs and activities in higher education. In this way, we intend to unpack both specific as well as general traits of ICARE as a collaborative infrastructure.

Case and setting

The context of this paper is the NSF-funded Interdisciplinary Consortium for Applied Research in Ecology and Evolution (ICARE) program. ICARE is situated at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County in the US, which is a medium-sized American university, built in 1969, with nearly 10 thousand undergraduate students, 3.5 thousand graduate students, one thousand faculty, and 2.5 thousand administrative and academic staff as of Fall 2023 (Faculty Development Center, 2023). While for the following section and the analysis, we mainly focus on the local practices in the ICARE program and among the Trainees, we later return to the wider institutional structures, as they impact the success and options available for building collaborative infrastructures in many different ways.

ICARE is a cross-sector, interdisciplinary network of environmental scientists and engineers in the Baltimore-Washington region as well as an interdisciplinary program that crosses institutional and disciplinary boundaries. The MSc students who are part of ICARE are called Trainees. The broader ICARE community includes faculty, graduate students, community agencies, governmental organizations, coalitions, community members, students, teachers, and policy professionals whose vision is to leverage the knowledge and skills of an emerging, diverse student body in ecology, environmental science, engineering, and social science research, and to empower those students for careers in which foundational research is used to solve environmental problems. Together, they aim to shape how scientific research is applied to environmental problem-solving at regional, national, and global scales.

ICARE overall was funded as a five-year grant program. In year 1, leadership focused on recruiting students from underrepresented backgrounds, interdisciplinary research team building, and collaborative curriculum development. Years two through five brought three cohorts of Trainees, the last of which will begin their second and final year in Fall 2024. As the grant funding winds down, ICARE leadership is transitioning toward the sustainability of the program at UMBC.

As part of the program, ongoing CoNavigator sessions were included. CoNavigator is an interactive tool designed to facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration and learning by providing a structured framework for mapping and visualizing ideas, goals, and concerns. It uses visual and interactive methods to help project participants from various disciplines align their expectations, communicate effectively, and integrate diverse perspectives. By guiding users through a step-by-step process of discussion and collective mapping, CoNavigator makes different viewpoints visible and tangible, fostering a deeper understanding and promoting teamwork. Specifically, the CoNavigator tool was used in three-hour sessions for the Trainees and their mentors and supervisors during one week in February each year. As seen in the overview below, the session included a series of steps, shifting between collective and individual participation and focusing on first identifying and mapping out all the elements of the project (1:what is it), moving into a discussion of ideas and visions for the project (2: what ought it be) and ending with literally building bridges and making decisions on how to proceed (3: what to do).

The tool has been used in teaching at UMBC since 2017 and the decision to incorporate CoNavigator into the ICARE project framework was driven by a commitment to enhance interdisciplinary collaboration, meanwhile supporting a sense of agency among the Trainees.

During the writing of the initial proposal, ICARE faculty devised a formal system of Principal Investigator and co-Principal Investigators, consultants, advisors, and evaluators. The PIs and co-PIs make up the formal leadership of the program, with the other personnel offering support or—in the case of evaluators—providing information to inform the decisions of the leadership team. The formal leadership has organized itself into several subcommittees taking on key pieces of the work (e.g. a Marketing and Recruitment, Research, and CoNavigator are each separate subcommittees). This was done to enable more efficient decision-making. Beyond the brain trust of the formal leadership team, there is one part-time program coordinator employed by ICARE to manage outreach and social media, maintain records, answer Trainee and partner questions, plan events, and coordinate internal meetings, tasks, and deadlines.

Methodology and analytical approach

In studying the ICARE program as a collaborative infrastructure, we are inspired by the idea of research as bricolage (Kincheloe, 2001; Kincheloe & Berry, 2004, Lincoln, 2001). This perspective views research as an iterative, adaptive, and creative process of assembling diverse methods and data sources. Bricolage, as conceptualized by Kincheloe (2001), emphasizes the researcher’s ability to critically transform and reimagine research methodologies, treating methods as flexible tools rather than rigid frameworks. Lévi-Strauss’s (1966) approach to qualitative research further supports this methodological stance, highlighting the importance of emergent strategies that allow for continuous interpretation and reconfiguration of research design.

This bricolage approach is visibly manifested through our research methodology, which dynamically integrates multiple methods and data types to comprehensively explore the ICARE program. Collected from 2021 to 2024 at various points throughout the year and involving different groups of informants, our data sources included observational field notes, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and survey responses.

Observations captured during CoNavigator sessions provided insights into how specific collaborative activities functioned in practice. Field notes documented the interactions, group dynamics, and negotiation processes that reveal the strengths and limitations of ICARE’s collaborative activities. Semi-structured interviews with Trainees, mentors, and faculty explored individual experiences with collaborative activities and perceptions of their effectiveness. These interviews directly addressed how ICARE’s strategies and tools influenced collaboration, as well as the challenges of working across organizational boundaries. Furthermore, collective reflections in focus groups highlighted how diverse stakeholders perceive ICARE’s integration with existing structures (e.g., master’s programs and the university). This method helped identify how collaborative practices contribute to the effectiveness of ICARE as an infrastructure. Finally, surveys were administered following CoNavigator sessions and after the summer research experience. These surveys captured quantitative and qualitative feedback on participant engagement with collaborative activities, such as CoNavigator, and their interdisciplinary training.

By drawing on varied materials at different research stages and leveraging diverse data sources, we adopt an action-research-inspired approach (c.f. Bartels & Wittmayer, 2018) that allows for iterative experimentation and continuous refinement of our understanding of the program’s dynamics. Particularly the external evaluation data collected was formative and intended to shape future iterations of the CoNavigator deployment within a large collaborative endeavor. Two of the authors are not only external researchers but also acted as facilitators or supporters for the CoNavigator deployments. Two of the authors were part of the team that initially developed the CoNavigator tool and have been deploying it in different contexts (www.CoNavigator.org).

An external evaluator (author 2) worked with the ICARE leadership team to conceptualize and embed evaluation data collection throughout the timeline of the ICARE program. CoNavigator sessions happen annually and evaluative survey results from participants were collected after each iteration. Additionally, we followed up with participants after the conclusion of the Trainees’ core summer research experience. Observations were conducted during the CoNavigator sessions to capture how the tool was used, the dynamics of group interactions, and the nature of the discussions. The surveys asked general questions about progress within the program but included specific questions focusing on CoNavigator and how, if at all, Trainees have engaged with the CoNavigator materials since their session. Evaluation data used in this paper primarily come from these surveys, but they also come from general comments made by Trainees, faculty, and mentors, as well as focus group and interview data generated from each of these participant types.

In the analysis, we shift between sharing and discussing examples from our anonymised observations, interviews, and survey material. This process was both deductive (guided by research questions) and inductive (emerging from the data). Some of the vignettes and quotes in the analysis are from situations experienced by all of us; others show details experienced by us individually and pieced together or supported by other types of data. The empirical data that we draw on in this paper are used to point towards examples and findings that we also see reflected in the wider literature.

Our relative embeddedness within the context of this deployment of the CoNavigator tool, combined with the multiple vantage points that we were able to access when collecting data about the impact and efficacy of the tool in this case, allow us to use our positioning analytically. While these different positions, viewpoints, and roles have enabled us to shed light on areas that would otherwise be in the dark, we are also aware of the blind spots and of some voices not being as loud as others. Nevertheless, we believe that the various in- and outside perspectives presented throughout the analysis contribute to the existing literature by comparing concrete experiences of collaborative practices in an interdisciplinary master’s program to ambitions of agency and widening participation at the policy levels of higher education. In line with the bricolage approach (Kincheloe & Berry, 2004), the main ambition in approaching the analysis this way has been to create what Svendsen et al. (2017) refer to as thickness by comparison, where the aim is not to create one coherent image, but instead add details and complexity to reach a deeper understanding of the case. Our descriptions and observations are richer and thicker through comparison.

In the following analysis, we will focus on three critical elements that were part of the collaborative infrastructures within the ICARE program. The first and most crucial element is the Trainees recruited to write their master’s theses as part of the ICARE program. These Trainees are not just participants but active agents who navigate and shape the collaborative landscape. We show how the Trainees’ roles evolved over time, the responsibilities they assumed, and the impact of their agency on the overall collaboration.

The second element involves the initial planning and establishment of foundational routes, including the introduction activities and the first CoNavigator sessions. These initial steps were designed to foster engagement, align expectations, and build a sense of community among participants. We comment on the effectiveness of these early activities in laying a solid foundation for subsequent collaboration.

The third element focuses on the second CoNavigator sessions and other activities aimed at enhancing support structures. In the analysis, we highlight the efforts to provide ongoing support and accommodate the evolving needs of the Trainees and other stakeholders. By examining these three elements—Trainees, initial planning, and expanded support structures—we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the collaborative infrastructures within the ICARE program, which we then build on in the discussion of the challenges and affordances of a conscious effort to building collaborative infrastructures in interdisciplinary education.

Building collaborative infrastructures

The ICARE Trainees

ICARE Trainees were recruited intentionally from underrepresented racial backgrounds, a choice flowing from one of ICARE’s core goals to diversify the ecological sciences workforce. Trainees are racially diverse compared with the student populations in the participating departments. Further, Trainees came to ICARE with a wide variety of prior experiences—in work, in research, in undergraduate majors, and in goals and priorities. Something unique about master’s programs in the United States, and which we saw with these Trainees in particular, is that very few of the Trainees entered ICARE directly after their undergraduate programs, meaning that these Trainees were already adults with some life experiences outside of academia.

Figure 1a, b below demonstrates the racial diversity of ICARE Trainees as compared with their enrolling departments. Overall, ICARE has succeeded in its goal of recruiting and training a more diverse set of master’s students when compared with the existing racial profile of master’s students in the participating departments at UMBC. Beyond being a signifier of success, this diversity is important to understand because it suggests variation in Trainees’ lived experiences within the United States and, therefore, radically different senses of agency and understanding of power structures. These differences give each Trainee a unique perspective on their role within, or ability to create, collaborative infrastructures within their own project teams.

a Race/ethnicity of ICARE Trainees. b Race/ethnicity within ICARE departments.

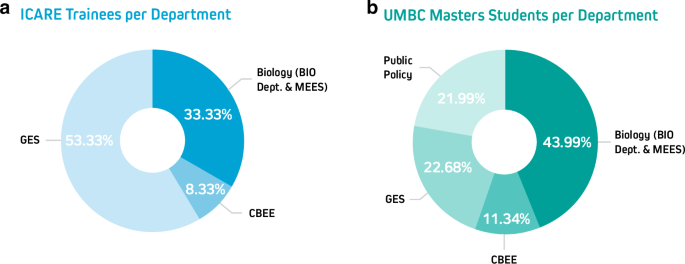

Figure 2a, b below shows Trainee diversity with respect to their disciplinary home at UMBC, as compared with the distribution of master’s students overall across the participating departments. ICARE Trainees are highly concentrated in Geography & Environmental Systems, but still have representation within the other departments, except for public policy. Diverse disciplinary backgrounds mean different ways of working with subjects and methods, different primary perspectives on a given problem, and a different array of solutions with which Trainees become familiar. These differing perspectives and approaches can again shape how a Trainee may create or understand collaborative infrastructures. Additionally, each discipline may have different models of collaborative infrastructures that act as norming mechanisms for Trainees.

a ICARE Trainees per department. b UMBC masters students per department.

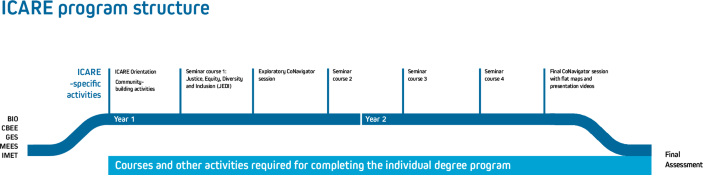

ICARE program structure

Upon acceptance into the program, Trainees are welcomed with a virtual session, including meeting prior Trainees (from cohorts 2 and 3). ICARE Trainees matriculate into one of five participating departments: Biological Sciences (BIO), Chemical, Biochemical and Environmental Engineering (CBEE), Geography and Environmental Systems (GES), the cross-campus Marine Estuarine Environmental Sciences (MEES)/IMET—Education, and the School of Public Policy. When Trainees come to campus for their first semester in the fall, they are immediately invited to an ICARE orientation and community-building activities among Trainees, and are informed about the required ICARE activities for the year. These activities are separate from and additional to any orientation or community events specifically coming from the enrolling departments. See the overview below:

During their first semester Trainees begin to discern a focus for their required research project, assemble their team of faculty mentor, partner mentor, and community mentor, and complete a one-credit seminar course on Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) in the environmental sciences in addition to the required curriculum for their degree program. Trainees form co-advised research teams with ICARE faculty and partners. Trainees, co-advisors, and relevant stakeholders participate in expert-facilitated, interdisciplinary training and research development sessions. Throughout the first semester, Trainees pull together their research objectives and form their core team. This occurs in the lead-up to the first CoNavigator session (as described in the case and settings section above) and is usually held early in the Trainees’ second-semester.

Trainees will take an additional one-credit seminar each semester of their program in addition to fulfilling all the requirements for their individual degree programs. The other seminars include practices in community-based research, professional writing, and professional speaking. In the summer between their first and second years, Trainees undertake the research activities that they will have spent Year 1 defining, refining, and planning. Each Trainee’s research is completed, analyzed, and written into a master’s level thesis during their final year of the program.

Throughout their 2-year master’s program, Trainees participate in weekly Research Lunches, which not only give them time to connect with other Trainees, but these lunches are also used to provide additional mentoring and coaching related to best practices in research, such as organizing references and managing a supplies budget. These topics are chosen to be relevant to Trainees’ concerns as they progress. A final CoNavigator session is held during Trainees’ final semester, often as they are in the process of finishing their thesis. Throughout their program, Trainees are supported in creating posters and presentations in order to develop their professional skills.

ICARE Trainees are brought into a highly structured environment. They are constrained by the requirements of the UMBC graduate school, by their degree program, by the requirements of the ICARE program, by the rigorous community-based research projects that they undertake, and by the general life circumstances of living in the Baltimore area. All these constraints shape Trainees’ sense of agency within their ICARE experience. In the next section we engage more deeply with the expert-facilitated, interdisciplinary training and research development sessions, which are a key moment in the infrastructuring of the Trainee-led research teams.

The first CoNavigator sessions

The purpose of the first CoNavigator session was to bring the groups together and align expectations around the focus and goals of their projects. This session aimed to explore important issues that concerned them both as individuals and as a group. Seven project groups signed up for the session, which was held in the wake of COVID-19, meaning everyone had to wear face masks on campus.

Although, as facilitators, we would have preferred to accommodate three to four groups at a time to collect research data through observation, due to logistical constraints, the groups were staggered, with one or two groups meeting at a time. As the ICARE staff wanted to experience the CoNavigator session, this arrangement meant that there were, at times, more observers than active participants in the room, which made the Trainees feel monitored and sometimes led the groups to approach the facilitator more frequently than they might have if more groups had been present. Furthermore, the staggered organization of groups meant that some of the mentors had no breaks between two sessions, and one of the supervisors had to shift groups midway, as their Trainees were in two simultaneous groups. The following vignettes offer a closer look at how two different teams engaged with the CoNavigator process and materials, highlighting the different roles taken on by Trainees:

In the situation described above, the group was physically in the same room for the first time, highlighting the novelty of the collaboration. The use of CoNavigator played a crucial role in supporting the group’s collaboration by providing a structured yet flexible facilitated dialog and idea exchange. The group members individually identified central aspects of the project, which were then merged into a collective map. The visual themes and statements on the table allowed them to discuss step by step the many different elements on the table and then find ways to cluster or categorize while pursuing various discussions and clarifications within the project framework. The exercise facilitated extensive discussion and revealed how different perspectives could complement each other. Kenan’s arrival thirty minutes late, highlighted the importance of proper introductions for group cohesion. In this case, the Trainee’s role was multifaceted as he took on the main responsibility for the group’s collaboration throughout the session, acting as a mediator, facilitator, and participant, also ensuring that Kenan was included and helping to guide the discussions. This highlights the potential for Trainees to take on significant responsibilities in shaping the collaborative process, although it also underscores the challenge of balancing these roles without clear guidance.

While CoNavigator’s structured steps facilitated the first group’s process by enabling discussions and exchange of perspectives, ultimately bringing the group together, the same tool supported an entirely different process in the second group, comprising the Trainee Olivia, her supervisor Yolanda, and a local partner, Evelyn. The three who were present know each other well and meet often, but one of their group members, a local stakeholder, is not present.

Overall, the group’s dynamics, discussions, and exercises provided valuable insights into the complexities and benefits of interdisciplinary collaboration. The integration of diverse perspectives and the focus on common goals helped them navigate challenges and work towards cohesive project outcomes. In observing the CoNavigator sessions, it became evident that the Trainees took on multiple roles within their projects, acting as brokers and bridges between various stakeholders. This multifaceted involvement highlights the extensive expectations placed upon them by other group members, with many stakeholders checking in and out throughout the project. The session underscored the complexity of managing a project with numerous stakeholders, each with their own interests and concerns. The diversity of these interests became particularly visible, illustrating the challenge of balancing different expectations and priorities within the collaborative framework.

During the sessions, it became evident that for some groups, this was the first time all members were physically gathered in one place. The students often took the lead in driving the group process, as they were typically the ones who had met everyone at least once. This underscored power hierarchies within the groups and highlighted the shifting roles and capabilities among members. Further, many groups were hybrid, presenting additional challenges. When stakeholders joined over Zoom or by phone for the final steps, they often assumed a significant role, sometimes overshadowing other members because they needed to be brought up to speed on the entirety of the discussion that had gone before.

Many groups faced challenges in determining which members should participate, leading to uncertainty and inconsistency in group composition. Additionally, late arrivals and remote participation further complicated the situation for some groups, contributing to a tentative start to the CoNavigator sessions. When parts of the consortium were missing, particularly partners or stakeholders, it led to a smoother interaction among the present members who were already loosely connected. However, the absence of key stakeholders meant missing perspectives, highlighting the importance of their involvement.

The figure below shows aggregated results from a survey administered at three-time points after the first CoNavigator session for each of the three cohorts of Trainees and their teams. While overall, the results are positive, indicating that all members of the team found CoNavigator a useful exercise, we can see that the level of agreement differed among participants based on their role type. For example, faculty members reported a higher level of agreement that they understood the purpose of CoNavigator prior to having participated in it. This could be explained by the fact that several of the ICARE leadership team were also faculty mentors; because of their prior knowledge of the tool and process, they may have felt more confident in their understanding than other members of the team (Fig. 3).

Example of CoNavigator flat-map. Photo of Trainee discussing their flat-map with their group.

Even though most participants reported planning to refer back to maps they had created during the CoNavigator session, when we followed up with participants after their summer research experiences, only four out of ten individuals across cohorts 1 and 2 reported having done so (cohort 3 is currently implementing their summer research project and has not yet been surveyed). This lack of follow-through on the intention to revisit the map is less the result of individual or small group mismanagement, but rather the outcome of a lack of infrastructuring around CoNavigator as a process rather than a singular event. There was no predetermined check in point set by ICARE to accomplish this, and given the multiple constraints discussed earlier, Trainees and their teams have a lack of time and capacity without the support of the ICARE infrastructure to make it happen.

The second CoNavigator sessions

The second CoNavigation was held when the students were nearing the completion of their project activities and were in the final phase of finalizing their theses. The purpose of the second CoNavigation session was twofold: first, to revisit the understandings, areas of interest, and goals of the collaboration established during the first CoNavigation. This was done using a flat-map, a poster version of the physical map from the previous year and the Trainees’ five-minute video recordings summarizing the discussion and key takeaways from their initial session. Second, the session had a more open format compared to the first CoNavigator session with a structured and collective facilitation. The groups had to decide themselves how and what they wanted to continue working on during the two hours available. The groups were in slightly different stages in their projects and on average, three to four groups were working at a time. Below is an example of a flat-map and a photo of one of the Trainees looking at their flat-map together with their mentor:

One group turned the workshop session into a facilitated supervision. They created a map of the different chapters of the Trainees’ thesis, identifying gaps and challenges while also highlighting where good work had been done and no further work was needed. This group had three members present, one of whom had not been part of the first round of workshops.

In contrast, another group, with all five members present, focused on conceptual clarifications. Here, the Trainee who took on the role of facilitator at the table using the various steps that were offered in a CoNavigator session more fluidly. The Trainee aimed to ensure that the associated stakeholders understood how their specific knowledge of a church community would be utilized for research purposes. This resulted in an extended exploration of power relationships between research infrastructure and local knowledge and the varying power positions open to different participants of the project group. The purpose of the discussions was both to align expectations with the project stakeholders but also to collect data for the project. Throughout the workshop, the Trainee had her Dictaphone on the table to record their discussions.

A third group, after reviewing their previous map, recognized the many areas they had covered topic-wise and how the project had taken a particular direction over the past year. This led them to focus on the storytelling aspects of the project. They spent their time creating a timeline to provide them with an overview of the many activities the group had succeeded in, which gave rise to mutual recognition. They also identified areas where there had been challenges, such as obtaining specific data that needed to go into the Trainee’s thesis. They then focused on finding solutions, and discussing further network and collaboration opportunities, one group member remarked: “these conversations do not just happen”.

Overall, the group members and the Trainees had the possibility to use the session space as they needed. The CoNavigator steps were visually projected on a PowerPoint in the room, but collective step-by-step instruction was not offered. Instead, the facilitator went from table to table to follow up on the group’s needs and offer the groups the individual steps of a CoNavigation when participants in the collaboration needed it or sought guidance to move on. All groups used the tiles and worked on forming a collaborative map but combined the following steps in various ways.

The flexible facilitation approach allowed groups to address their specific needs and focus areas, fostering a more tailored and productive session but not a format that suited everyone. However, some groups experienced challenges with the timing of the session, feeling it was too late in the project timeline, as it was scheduled just a month before the thesis submission deadline. Additionally, the absence of some group members during the first CoNavigator session posed difficulties in maintaining continuity and cohesion.

The second CoNavigator session demonstrated the value of flexible, participant-driven workshops in interdisciplinary collaboration. By revisiting initial goals, accommodating diverse approaches, and addressing timing and participation challenges, the session provided a platform for groups to realign their focus and work towards cohesive project outcomes. The external stakeholders were also experiencing greater agency and comfort, they understood their role and how to engage in the project better.

Sustaining and developing collaboration

While the first section focused on the Trainees, the second on the CoNavigator sessions, this third analysis section will primarily examine the role of facilitated and non-facilitated processes in building collaborative infrastructures. The ICARE model includes defined support structures for Trainees as well as mentors. Upon joining the program Trainees are given opportunities to connect with cohort members even before coming to Baltimore. When they arrive, Trainees are provided an orientation to ICARE and the Baltimore Harbor region. They also participate in cohort-building activities, such as the popular “Canoe and Scoop” where Trainees go collect trash out of a local waterway. These structures are crucial for helping settle Trainees into the area and building connections, as one Trainee reflected about the orientation, “I loved it! It made me feel extremely connected to the ICARE and UMBC community.”

A core piece of infrastructure is four required 1-credit courses—one per semester. These courses are intended to provide the foundational and unique coursework that makes ICARE unique among graduate programs. These classes are open to other students who are not ICARE Trainees. An advantage of this is that it makes the courses more robust and integrated into existing course structures; however, it also introduces a challenge in that these other students can bring different types of prior knowledge and expectations into the course and thus affect the conversations in different ways.

One Trainee talked about the inclusion of non-ICARE students into the seminars, “…having those other people was slowing our conversation down. If you are in ICARE you are already ready to have higher level conversations, but we ended up having surface level conversations. If they want to offer those classes to other people, have a different section.” (quote from evaluation, cohort 2)

Trainees gave several points of feedback about the Writing course that they experienced. “I didn’t get any feedback on my writing, when I knew my advisor would have torn it apart. I knew it had errors, but the feedback I got was always just that it’s great.”(quote from evaluation, cohort 2). Trainees suggested that the writing course could be more connected to ICARE and geared toward technical writing more than blog posts. Specifically, the Trainees would have liked the structure to work more directly on their theses, and to get critical feedback from the instructor.

Additionally, Trainees may have felt isolated over the summer in the absence of the regular cohort check-ins that they had become accustomed to during the academic year. One Trainee explained, “The summer felt relaxed which was a nice change from the semester, but it also felt lonely. Throughout the semester we have weekly research lunches where we both connect with our cohort and get a lot of support from ICARE PIs. Then suddenly, we are left for 3 months without any of that structure. It would be good to have a lunch or get-together every other week at least to continue that support.” (Free response answer from survey, cohort 1 Trainee).

To support Trainees’ advancement through their degree programs, ICARE leadership created a sample timeline from their summer research project to thesis completion. Trainees are also intentionally connected to other campus entities, such as writing support and career services.

As Trainees progress through the ICARE program, there are several other support structures that have been put in place. For example, Trainees meet weekly for a “research lunch” which is an opportunity to gather together, and regularly features guest speakers. Support structures are not only intended to enable Trainees to effectively leverage ICARE, but also work to support the various mentors and stakeholders. Trainees and mentors participate in a session with an outside mentoring expert, receiving guidance in mentoring best practices (for faculty) and skills in self-advocacy (for Trainees). Faculty mentors and Trainees also sign mentoring agreements outlining some of the core expectations and norms for mentees and mentors alike. In addition to these support structures, various activities were planned to support the collaboration between the Trainees and their teams. One of these activities was a second co-navigation session, scheduled as part of a broader celebration day. The celebration day included a poster session where Trainees would create scientific posters highlighting the findings of their project and their accomplishments over the past year. Invitations were extended to fellow students both on and off-campus, project members, all faculty, and a specially invited keynote speaker from the political realm focusing on environmental justice, who delivered a talk.

It is important to note that not all of these elements of infrastructure were present from the beginning of the project. Many of these elements, such as the Canoe and Scoop activities, the creation of mentoring agreements, and the development of a sample timeline to thesis completion, emerged over the course of the first year of implementation as we conducted evaluation activities and learned from participants what their needs were. Infrastructuring is an active process requiring feedback loops and continuous attention. This demonstrates the empiric nature of ICARE as a program, learning and shifting as participants engage with the infrastructure of the program and are either supported by it or not.

Lastly, throughout this paper we have been discussing the infrastructure of the CoNavigator sessions to enable greater collaboration across all members of the Trainees’ research and mentoring teams. Beyond the sessions themselves, there was little to no infrastructuring of CoNavigator, which would have enabled it to function more as a process than an event within the broader scope of the ICARE program infrastructure.

Discussion

In the analysis above, we looked at the Trainees, the staff, the CoNavigator tool, the courses and other activities as various elements of the collaborative infrastructure in ICARE. In the following, we now discuss the roles and connections between these elements. We end by asking what to learn from this case.

Trainees as central actors in infrastructure building

Trainees within the ICARE program often found themselves at the forefront of the collaborative process, shouldering significant responsibilities without the corresponding power or support typically afforded to such roles. This dynamic reflects a common issue in interdisciplinary programs, where students, by necessity, become key players in mediating between different disciplines and stakeholders. The concept of “responsibility without power” aptly describes the situation many Trainees faced, as they were often the only ones available to lead and coordinate activities within the program. While this position provided them with a sense of agency, it also placed an unfair burden on them, as they lacked the formal authority or resources to effectively manage these responsibilities.

The learning outcomes for Trainees in this context were both broad and deep, though often fragmented. The necessity of navigating a vast field of knowledge across multiple disciplines meant that Trainees gained specialized competencies deeply rooted in practice. However, the lack of coherent, collective guidance sometimes led to superficial learning experiences, where the broader connections between disciplines were not fully realized. This situation underscores the importance of clear role definitions and structured support in interdisciplinary programs to prevent over-reliance on student initiative and to ensure a more balanced learning experience.

Looking at the development from the first cohort of Trainees that started during the Covid pandemic to the last cohort finishing this Spring, there seems to have been a shift in drive: The first years were more unstructured, with fewer scaffolding activities around the Trainees, and more ad hoc decisions being made; however, this also meant that the Trainees and external stakeholders took it more upon them to ensure progress and movement in the projects. And while the later cohorts had more infrastructure surrounding them and perhaps a stronger social community among the Trainees, they were not more satisfied with the program, compared to the first cohort. This points towards a progression from a basic setup, with few support structures and a high degree of participant-led improvisation and sense of pioneering, towards a more established infrastructure, with more space to focus on the individual projects and processes, but perhaps also a lower degree of ownership. When formal institutional structures are weak, participants become primary infrastructure builders, negotiating roles and responsibilities through practice.

Staff and faculty as mediators of collaborative tools

Staff and faculty members also played a critical role in facilitating the use of collaborative tools like CoNavigator, yet their effectiveness was often hampered by the absence of a robust infrastructure. The variability in their ability to mediate and interpret these tools resulted in uneven experiences for Trainees. In the early stages of the program, the lack of experience with CoNavigator among staff led to a situation where Trainees were forced to take the lead, sometimes without adequate preparation or understanding. As staff and faculty gained more experience with the tool in subsequent sessions, the dynamic shifted slightly, with Trainees feeling more supported and empowered to take charge. However, this shift highlights the importance of ongoing professional development and support for faculty in interdisciplinary programs to ensure that they can effectively guide and support Trainees.

The variability in staff engagement also points to a broader issue within the program: the lack of alignment in expectations across different levels of the institution. While the literature on supervision emphasizes the need for aligning expectations (Gatfield, 2005; Gurr, 2001; Palmer et al., 2023), this was not explicitly addressed within the ICARE program. This oversight led to discrepancies in how different stakeholders—Trainees, staff, local community members, and university leadership—interpreted their roles and responsibilities, further complicating the collaborative process. Through the analysis, we found that continuously aligning expectations and negotiating the didactical contract (Brousseau & Warfield, 2021) are crucial elements of building and maintaining successful interdisciplinary collaboration.

Administrative support and institutional challenges

The role of administration in the ICARE program was characterized by a notable lack of visible support, particularly from the then-current university leadership. Despite the program’s alignment with the university’s strategic goals and its status as a flagship initiative, there was insufficient backing to effectively embed the program within the institutional structure. This lack of support became particularly evident during high-profile events like the CoNavigator Day, where the absence of university management highlighted the challenges of securing institutional buy-in for interdisciplinary initiatives.

This situation reflects a broader challenge in the institutionalization of interdisciplinary activities, as described by Holley (2019), Klein (2010, 2013), and Lindvig and Hillersdal (2019). Even within a single institution, the degree of support for interdisciplinary programs can vary significantly, leading to a fragmented infrastructure that fails to adequately support the program’s goals. The ICARE program’s experience underscores the need for consistent and visible administrative support to build and sustain collaborative infrastructures that can effectively support interdisciplinary education.

The ICARE program is an example of how collaborative infrastructures in interdisciplinary education emerge through complex, dynamic processes of negotiation and adaptation across organizational boundaries. By examining the roles of Trainees, staff, and administrative structures, we observed how infrastructure development is fundamentally participant-driven, with power dynamics and institutional support critically influencing collaborative effectiveness. Our study shows that successful interdisciplinary infrastructures require continuous alignment of expectations, flexible role negotiations, and consistent institutional backing, even for programs deliberately positioned outside existing structural boundaries.

Conclusion and further perspectives

We began this paper with a quote by Kleinberg, voicing the concern for over-institutionalizing interdisciplinarity. Using ICARE as a case, we then explored the potentials of flexible pathways, by analyzing how collaborative infrastructures were built and developed. Employing a mixed methods approach inspired by the idea of research as bricolage and drawing on observations, interviews, and surveys, we found that an interdisciplinary master’s program can indeed develop in monodisciplinary structures without being institutionalized. Drawing on the work of Selloni (2017), we did find that the ICARE program showcases several of the ideal characteristics of a collaborative infrastructure, by being empiric, modular, formatted, situated, hybrid, and weak—perhaps even too weak. Although Selloni defines weak as light, relational, and with diverse and incoherent activities, she also points to “‘weak, in the sense that it is not a fixed and absolute entity with clear boundaries” (p.137). The roles of the ICARE Trainees, staff, and administrators are crucial in building and sustaining the collaborative infrastructures, and while the program’s flexibility allows for organic development, it also necessitates continuous alignment of expectations, institutional support, and the active engagement of all participants in the infrastructure process. In addition to this, a lack of visible institutional support and transparency makes it difficult to build a strong and enduring collaborative infrastructure.

The challenges experienced in creating and sustaining a collaborative infrastructure within ICARE mirror dynamics found at higher institutional levels. As discussed by Holley (2019) and Klein (2010, 2013), adding interdisciplinary activities and programs to monodisciplinary institutions is a risky endeavor. These initiatives are often praised and used to promote the institutions but are rarely structurally embedded or given a budget line. Our study of ICARE at UMBC confirms that the institutionalization of interdisciplinary education is situated, undetermined, and diverse, varying greatly even within the same institution. Collaborative infrastructures often center around individuals rather than institutions, pointing to a general lack of infrastructure in collaborations, such as visible and intentional planning and alignment of expectations.

This finding emphasizes the necessity of viewing collaboration as an ongoing process rather than a one-off event. Employing a physical tool for interdisciplinary collaboration can help maintain a focus on collaborative infrastructuring as a constant process, emphasizing “infrastructuring” as a dynamic verb rather than a static noun. While ICARE and the use of CoNavigator is a situated and unique case, it can hopefully serve as a catalyst for discussing infrastructure needs and highlighting infrastructure gaps linked to new interdisciplinary activities.

Responses