Efficacy and safety of sacituzumab govitecan Trop-2-targeted antibody-drug conjugate in solid tumors and UGT1A1*28 polymorphism: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

Sacituzumab govitecan (SG or IMMU-132), a novel antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) was approved by US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Owing to its unique combinatorial design comprising a cytotoxic semi-synthetic camptothecin SN-38, a CL2A linker and trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2 (Trop-2)-specific humanized monoclonal antibody, SG represents a new generation of targeted therapy designed to improve drug delivery by virtue of targeting Trop-2 which is highly overexpressed in diverse epithelial solid tumors [1]. It has a high drug-to-antibody ratio of 7.6 that allows for the release of high concentrations of the payload, SN-38 both intratumorally as well as within the surrounding tumor microenvironment.

The highly favorable therapeutic window of SG is accounted for by its much-improved pharmacokinetics characteristics over conventional irinotecan. Conventional irinotecan is converted by hepatic carboxylesterases into the active metabolite, SN-38 which exerts its antitumor effect by inhibition of topoisomerase I during DNA replication. SG has a long half-life of 16 h whereas free unbound SN-38 has a half-life of 18 h. Moreover, a 20- to 136-fold increase in SN-38 exposure level was detected in SG-treated xenograft tumors over that of irinotecan, indicating a superior intratumoral delivery of SN-38 by SG compared with conventional irinotecan [2]. The release of SN-38 moiety at low pH conditions prevalent in the tumor microenvironment further protects against premature glucuronidation by intestinal uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A) enzymes [3].

To date, SG has been evaluated in several clinical trials demonstrating modest to good clinical activity in different tumor types. The first-in-human study conducted in a basket trial cohort of epithelial tumors including colorectal cancer (CRC), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) and small cell lung cancers (SCLC) reported a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 3.6 months [4]. Another study reported PFS durations ranging 6.7–8.2 months in six metastatic, platinum-resistant urothelial carcinoma (UC) patients [5]. Larger-sized trials observed a median PFS of 6.0 months in metastatic TNBC while 3.7 months and 5.2 months were recorded in SCLC and non-small lung cancers (NSCLC), respectively [6, 7]. Subsequent phase 2 studies reported improved durations of response with median PFS of 7.2 months in metastatic UC patients and 5.5 months in hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancers [8, 9].

The median overall survival (OS) also differed between tumor types with shorter OS observed in small-cell and non-small cell lung cancers (7.5 months and 9.5 months, respectively) [6, 7] compared to patients with breast cancer and metastatic UC with median OS durations ranging from 10.9 to 16.6 months [8,9,10,11]. Thus, these differences in survival outcomes may be due to differences in clinical activity of SG in various tumors.

Current reports imply that occurrence of treatment-related adverse events (AE) with SG have been conflictive and vary across different studies. Two phase 2 studies in mUC and TNBC reported that grade 3 and higher neutropenia accounted for 35% and 39% respectively [9, 10], whereas in another NSCLC cohort, 28% of patients developed severe neutropenia. Two basket trials also reported over 50% of patients had grade 3 and higher neutropenia, particularly in patients harboring at least one defective allele of UGT1A1*28, a genetic polymorphism in the gene encoding for UGT1A1 that is associated with reduced metabolism of irinotecan [12]. These studies observed that a greater proportion of homozygous UGT1A1*28 patients experienced treatment-induced severe neutropenia compared with non-carriers [11, 13]; suggesting that accounting for UGT1A1 genotype status may be useful in improving SG-induced toxicities in patient carriers.

Although the clinical utility of UGT1A1 genotype-guided dosing has been clearly demonstrated with conventional irinotecan and other irinotecan-containing regimens [14,15,16,17,18,19] and found to be cost-effective, the current FDA-approved SG dosing guidelines remain conservative. The UGT1A1 genotype-association findings from the IMMU-132-01 trial were mostly deemed as exploratory due to the low frequency of UGT1A1*28 alleles in the study cohort [20, 21]. Nevertheless, the recent phase 3 ASCENT trial also alluded to the importance of genotype-directed dosing as treatment-related AEs were higher in patients with the UGT1A1*28/*28 genotype compared to heterozygous or wild-type patients, although the authors were unable to recommend any genotype-associated dosing due to the limited number of UGT1A1*28 homozygotes [22].

Therefore, given these conflicting reports in individual clinical studies, we sought to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis on the safety and efficacy outcomes of patients receiving SG for the treatment of solid tumors and the influence of UGT1A1 genotype status on these clinical outcomes.

Methods

Search strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used to perform the meta-analysis. The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, # CRD42022359943). Publicly available databases PubMed, Embase and Cochrane were searched using the following search terms: “sacituzumab govitecan” OR “sacituzumab govitecan-hziy” OR “IMMU-132” on February 15, 2024. All the studies published till 15 February 2024 were retrieved and reviewed. A manual search was also conducted to browse reference lists of eligible articles and other relevant review articles. Abstracts, conference proceedings, articles in press and case reports were omitted from review and analyses.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients who received at least one dose of SG and enrolled as part of original study were included in the analysis. This study considered all observational (cohort, cross sectional, and case control) studies and randomized controlled trials (RCT). Full study reports written in English or abstract written in English were retrieved and assessed for their eligibility. Studies for which the abstract or full-text was not available, duplicates, reviews, conference abstracts, case reports, preclinical (animal and in vitro), commentary and case series were excluded.

Study selection

Duplicates identified in the full list of studies were removed. The articles titles and abstracts retrieved from the electronic and manual literature searches were independently reviewed by the authors for eligibility. Articles deemed potentially eligible were subjected to full-text retrieval. The selected articles were independently assessed for completeness and final inclusion by two authors (SC and RS). Discussion and consensus were reached to resolve any disagreements observed during study selection.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines. Baseline study information retrieved from each article included the name of first author, name of journal, year of publication, PMID (if available), tumor type, sample size, median age of patients (years), sex, SG dose (mg/kg), ethnicity, UGT1A1*28 status, toxicity events (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, fatigue), duration of follow-up, objective response rate (ORR), survival outcomes (PFS, OS). The qualities of the included studies were assessed, and the risks for biases (RoB) were refereed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality assessment tool for the cohort and RCT studies [23, 24]. The evaluation tool for cohort and RCT studies comprised of 11 and 13 parameters, respectively. Each satisfied parameter was scored as 1 if not 0. When the information provided was not satisfactory to assist in deciding on a specific item, we agreed to grade that item as 0. The RoB was categorized as low (>70%), moderate (50–70%), and high (<50%). Data extraction and quality assessment were independently performed by two (SC and RS) reviewers and disagreements among the review authors were achieved by consensus.

Deviation from study protocol

Protocol stated that analysis would be done using random effects model with the DerSimonian and Laird inverse variance. Most of the included studies in the study were observational and few were clinical trials. Hence, individual studies were pooled using single arm generic inverse variance method with two exposure groups, namely, “UGT1A1 genotype” and “non-specific UGT1A1/non-reported group” and both groups were compared for different outcomes. A separate group analysis based on different UGT1A1 genotype groups were also carried out for primary outcome only. This is “addition” type of deviation.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed for all included studies with sufficient available data. All meta-analyses were specified to be performed for patients with “UGT1A1 genotype” versus “non-specific UGT1A1/non-reported group” specifications. Safety outcomes were measured using toxicity events such as neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, diarrhea, fatigue, vomiting and nausea while efficacy outcomes were measured using median PFS and median OS. Primary outcomes (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, fatigue) were treated as binary data while secondary outcomes such as median PFS/OS were treated as time-to-event. Reported aggregated data were used for analysis. As the meta-analysis included single-arm studies, proportion of events and median values were pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird inverse variance method, similar to approaches used by Lueza et al. [25] and Wei et al. [26]. The random effects model was chosen due to expected heterogeneity between studies. The pooled effect with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) and p-values were also calculated and results were presented as forest plots. Safety outcomes were reported as percentages with 95%CI while secondary outcomes were reported using median values with 95%CI. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic and Χ2 test. Subgroup analyses aimed at comparing the toxicity profile between UGT1A1 genotype groups, i.e. UGT1A1*1/*1 (Wild type), UGT1A1*1/*28 or UGT1A1*1/*6 (Heterozygous) and UGT1A1*28/*28 or UGT1A1*6/*6 (Homozygous) were carried out. Publication bias was accessed using Egger’s test [27, 28]. All tests were two-sided with p value < 0.05 considered statistically significant, and analysis was performed using ‘meta’ package of R software version 4.2.0.

Results

Literature search results and characteristics of studies evaluated

Our search strategy yielded a total of 1663 results from three databases of Pubmed, Embase and Cochrane, of which 420 were duplicate records removed prior to screening, 1181 records excluded during screening based on title and abstract contents (Fig. 1). An additional 42 reports were excluded after retrieval as they were either clinical trial registrations, clinical trial protocols, summary, or biomarker-based studies. Six clinical trial reports with overlapping cohorts were also omitted from analysis [8, 10, 11, 21, 29, 30] Finally, 11 full-texts articles were included in this meta-analysis.

PRISMA 2020 Flow diagram for systematic reviews.

Study characteristics

The characteristics and patient demographics of clinical trials that were eligible for analysis is listed in Table 1. Out of 11 included studies, eight were cohort studies [4,5,6,7, 9, 13, 31, 32], two were RCT [22, 33] that evaluated SG versus chemotherapy versus treatment physician’s choice and one was a real-world evidence (RWE) report [34]. Results reported by O’Shaughnessy et al., Bardia et al. from the ASCENT trial [21, 29] were not considered as separate studies and were excluded from the present analyses. Similarly, primary results from the TROPiCS-02 study reported by Rugo et al. were excluded [35]. A total of 1578 patients were included in the meta-analysis with number of patients in each study ranging from 6 to 496 patients. The median age of the patients was 61.0 (range: 29-90) years. Studies comprised of patients harboring various tumor types such as metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC), small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), colorectal cancer (CRC), esophageal, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), endometrial, UC and other epithelial malignancies. Majority of patients were female (62.2%). All 11 studies reported ethnicity whereby White Caucasians comprised over 85.7% of the studied cohorts. UGT1A1 genotype information was available for only five (45.5%) studies [9, 13, 22, 31, 32] and further genotype-stratified data were only available for six studies [8, 9, 13, 31,32,33]. A total of four studies [9, 22, 32, 33] administered SG dose at 10 mg/kg, while three dose expansion studies [6, 7, 31] evaluated two SG doses at 8 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg; and remaining three studies [4, 5, 13] explored several SG doses ranging from 8 mg/kg to 18 mg/kg. Separately, Reinisch et al. reported that 10 mg/kg dose was used in all but eight patients who were treated at a starting dose of 7.5 mg/kg [34]. SG dosage stratified by genotype group indicated 62.0% patients received 10 mg/kg in the non-specific UGT1A1/non-reported group while 89.1% received the same dose in the UGT1A1 genotype reported group (Supplementary Table 1).

Risk of bias analysis

Based on JBI tool, five [6, 7, 9, 13, 34] and four [4, 5, 31, 32] cohort studies were assigned as having moderate and high RoB respectively while two [22, 33] RCT trials were assigned as having low level of RoB (Fig. 2).

Risk of Bias of included (a) randomized controlled trials (b) observational studies. Risk of bias summary for all (c) randomized controlled trials (d) observational studies.

Safety data

In general, the pooled prevalence of different toxicities were higher in UGT1A1–genotype reported group compared to non-specific UGT1A1/non-reported group. However, no statistical significance was observed between the groups in any toxicity. The gastrointestinal (GI) toxicities including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea of any grade was lower in the non-specific UGT1A1/non-reported group than that of UGT1A1-genotype reported group. No discerning differences in frequency of GI events, nausea (46.6% (95%CI: 26.9–66.3) vs 57.9% (53.6–62.3)) and vomiting (24.2% (12.3–36.1) vs 35.5% (24.6–46.5)) were observed. Prevalence of diarrhea were also similar in both non-specific UGT1A1-/not-reported group and the UGT1A1-genotype reported group (44.9% (30.1–59.7) vs 54.3% (47.9–60.7)). Hematological events such as neutropenia and febrile neutropenia of any grade occurred in similar prevalence in the two groups: neutropenia 39.4% (22.1–56.7) vs 60.5% (49.0–72.0) and febrile neutropenia 4.4% (1.8–6.9) vs 5.2% (3.7–6.8), whereas fatigue was equally prevalent in both groups at 41.4% (28.2–54.6) vs 42.9% (35.3–49.4), Overall I2 varied between 0% to 92% for all safety outcomes. (Supplementary Fig. 1).

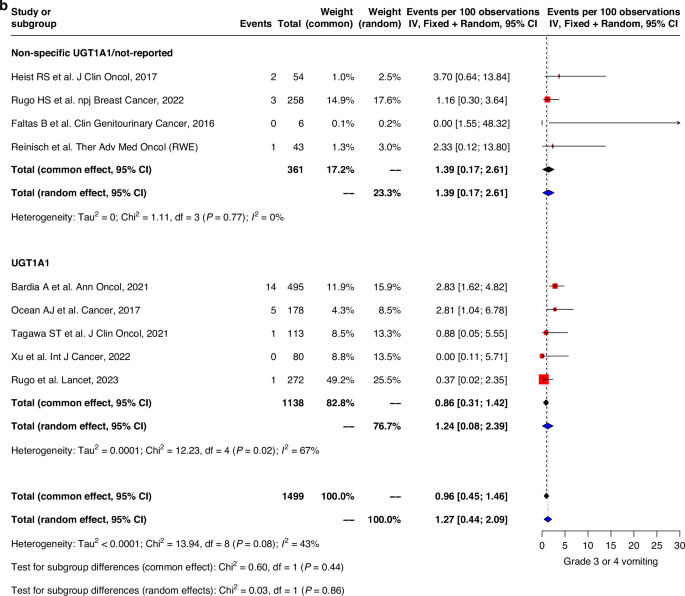

Similar trends were observed with grade 3–4 adverse events where GI events were generally higher in studies with UGT1A1 genotype data compared to those without specified/reported UGT1A1-genotype information. Pooled prevalence of grade 3–4 nausea and vomiting were 2.0% (0.5–3.5) vs 3.2% (1.4–5.0) and 1.2% (0.1–2.4) vs 1.4% (0.2–2.6) respectively in both groups (Fig. 3a, b). Grade 3–4 diarrhea was also higher in the non-specified UGT1A1/not-reported group compared to UGT1A1-genotype reported group (10.2% (7.3–13.0) vs 7.2% (4.6–9.8)) (Fig. 3c).

Forest plots of (a) grade 3–4 nausea, (b) grade 3–4 vomiting, (c) grade 3–4 diarrhea, (d) grade 3–4 neutropenia, (e) grade 3–4 febrile neutropenia, (f) grade 3–4 fatigue.

The prevalence of grade 3–4 hematological toxicities was similar in both groups. Grade 3–4 neutropenia were less prevalent in the non-specific UGT1A1/non-reported group compared to UGT1A1–genotype reported group (39.4% (22.1–56.7) vs 60.5% (49.0-72.0)). Severe febrile neutropenia was also lower in the non-specific UGT1A1/non-reported group (4.4% (1.8–6.9) vs 5.2% (3.7–6.8)) compared to that of the UGT1A1 genotype group. Similar trend was also observed in fatigue with pooled prevalence 4.5% (1.7-7.3) and 5.8% (4.5–7.2) in non-specific UGT1A1/non-reported group compared to UGT1A1 genotype group (Fig. 3d–f). Sensitivity analysis, after excluding high risk of bias studies, showed similar trends for all grades and grade 3–4 of safety outcomes (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). Genotype subgroup analyses were also performed with outcomes diarrhea, grade 3–4 diarrhea, febrile neutropenia, grade 3–4 febrile neutropenia, neutropenia and grade 3–4 neutropenia (Supplementary Table 3).

Efficacy data

Pooled ORR in both UGT1A1 genotype and non-specific UGT1A1/non-reported groups were similar, with an average of 15.1% (9.4–20.8) and 23.5% (12.8–34.1) observed respectively (Fig. 4). Pooled median PFS and OS evaluated for all studies was 4.9 months (95%CI: 4.0–5.8) and 9.6 months (7.6–11.6) respectively. No significant differences in PFS and OS durations were observed between UGT1A1 genotype group and non-specific UGT1A1/non-reported group. (Fig. 5). Similar trend was observed for pooled analysis of studies with low and moderate risk of bias. (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Forest plot of objective response rates.

Forest plots of (a) progression-free survival and (b) overall survival.

Assessment of reporting bias

Based on the Egger test results, possibility of reporting bias couldn’t be excluded for safety outcomes (Supplementary Table 2). However, an asymmetric funnel plot could have resulted from multiple factors, such as e.g. selection bias, true heterogeneity and methodological flaws.

Discussion

The clinical successes of SG in breast cancer and urothelial carcinoma have resulted in a surge in new clinical studies evaluating SG as a single agent, in combination with chemotherapy or immunotherapy. SG has definitively demonstrated favorable clinical activity in breast cancers while its efficacy in other solid tumors has not been fully explored. Hence, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the safety and efficacy outcomes of SG in different solid tumors as well as the role of UGT1A1*28 genotype in predicting pharmacodynamic outcome measures.

In this meta-analysis, 11 clinical studies representing a wide spectrum of solid malignancies (TNBC, SCLC, NSCLC, CRC, esophageal, PDAC, CRPC, endometrial, UC and other epithelial tumors) were evaluated for SG efficacy, toxicity, and the prognostic role of UGT1A1 genotype. The median PFS and OS durations of 4.9 and 9.6 months respectively indicated that SG confers moderate disease control across different tumor types. The observed wide heterogeneity in tumor response may likely be due to differential Trop-2 expression resulting in varying degrees of SG sensitivity. Efficacy outcomes and adverse events were similar regardless of UGT1A1 genotype information, probably due to small sample size of the various studies included in the meta-analysis and the lack of UGT1A1 genotype information in over 50% of studies analysed (Refer to Table 1). Nevertheless, our summary of ROB analysis showed that in overall, this review had a low risk of bias (Fig. 2c, d), implying that the overall quality of the studies reviewed is high and study findings are in fact reliable.

The pivotal ASCENT study was the first study that demonstrated the superiority of SG over single-agent chemotherapy (eribulin, vinorelbine, capecitabine or gemcitabine), resulting in its accelerated approval by FDA for patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic TNBC. SG conferred a significantly longer PFS over physician’s choice of chemotherapy (5.6 vs 1.7 months), approximately twice as long OS duration (12.1 vs 6.7 months) and a 7-fold improvement in objective response (35% vs 5%) [21]. The Phase 3 randomized TROPiCs-02 study reported a similar outcome in HR + /HER- metastatic breast cancer, with a slight improvement of median PFS (5.5 vs 4.0 months) and ORR (21% vs 14%) over that of physician’s choice of chemotherapy [21, 35]. The most commonly reported treatment-associated adverse events were grades 3–4 myelosuppression (neutropenia, leukopenia) and diarrhea but were largely manageable and similar to that of chemotherapy and was not major contributors for treatment discontinuation [21, 35]. Together, these trials have established SG as a promising third-line agent in metastatic TNBC and HR + /HER- breast cancers.

Furthermore, given the primary role of UGT1A1 in the metabolism of SN-38, the cytotoxic payload of SG and the known impact of UGT1A1 genetic polymorphisms on SN-38 glucuronidation, we sought to ascertain the influence of UGT1A1 genotype status on SG clinical outcomes and toxicities.

Our results imply that the anti-tumor activity and survival benefit of SG differed greatly across different tumor types. The ORR in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies such as CRC and PDAC compared to their counterparts with other types of malignancies were poorer. A possibility for this abysmal response rate is the low expression of Trop-2 in these non-sensitive tumor types.

Trop-2, also known as tumor-associated calcium signal transducer, is a novel drug target overexpressed in numerous solid tumors [1]. As a 35 kDa glycoprotein spanning across the transcellular membrane, Trop-2 acts as a transducer of intracellular calcium signaling and plays a crucial role in the activation of cell proliferation via the MAPK pathway to result in downstream regulation of invasion, migration and survival of cancer cells [36]. Trop-2 is also implicated in the regulation of stem cell growth and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) processes wherein Trop-2-expressing prostate basal cells, hepatic stem cells and endometrial cells exhibit regeneration, self-renewal and cell differentiation characteristics [37,38,39] and induces EMT via the PI3K/AKT pathway [40]. Absence of Trop-2 expression in certain tumor types such as breast and prostate has been associated with worse prognosis whereas high expression of Trop-2 related genes such as CDH1 and ITGA6 were indicative of improved recurrence-free survival [41]. Hence, overexpression of Trop-2 in numerous solid malignancies of breast, colorectal, lung, gastric, esophageal and pancreas and its clear involvement in increased tumor growth, proliferation and metastasis have led to its recognition as a strong prognostic marker and promising therapeutic target [42].

However, current immunohistochemistry data remains confounding. While detection of strong Trop-2 staining was observed in various breast subtypes and associated with lower disease grade [43], it is apparent that Trop-2 expression is not always a clear indicator of disease aggressiveness. In breast carcinomas of no special type, a higher proportion of G3 tumors had weak staining (12.3%) compared to that in lower G1/G2 tumors (8.4%) whereas approximately 75% of G1 tumors had strong Trop-2 staining versus 52% in G3 tumors. As one of the more aggressive forms of breast cancer, TNBCs demonstrated a wide heterogeneity in Trop-2 expression whereby 20% of tumors were weakly staining versus 9% in non-triple negative tumors. Conversely, moderate staining was observed in 24% of TNBCs compared to 31% in non-triple negative tumors [43]. Of note, the heterogeneity among the histological subtypes within TNBC tumors may explain the observed differences in Trop-2 expression within this form of breast cancer [43, 44] and previously known proliferative role of Trop-2 appears to be distinct from disease severity and tumor aggressiveness.

At present, the clinical utility of Trop-2 as a biomarker for predicting response is still unknown. TNBC patients from the ASCENT study with medium to high Trop-2 expression derived greater clinical benefit from SG compared to chemotherapy [45]; suggesting that high Trop-2 expression could be a pre-selection criteria for initiating patients on SG treatment. However, this may not be applicable to all tumor types. Only 10% of CRC tissues stained strongly and high Trop-2 expression was associated with advanced staging and nodal metastasis [43]. Given the poor response reported in two basket trials (ORR = 3.23%), it is possible that not all CRC patients would benefit from SG [4, 13]. Similarly, despite the highly positively-stained Trop-2 cells in PDAC tumors [43], SG appears to be limited in disease control where null response was reported amongst the 16 patients [13]. Apart from breast cancers, the overall associations with Trop-2 expression and response in other tumor types remain inconclusive due to a lack in Trop-2 expression data in studies reported thus far. As these observations are non-confirmatory due to small cohort sizes in basket trials, it is envisaged that perhaps larger trials may be needed to clarify the clinical utility of Trop-2 testing.

It might be speculated that the lack of SG efficacy in certain tumor types may be due to inclusion of patients who were refractory to irinotecan-based regimens. Exclusion criterion from assessed studies did not specifically state whether such patients were recruited or excluded from analysis. Therefore, to intrinsically determine SG efficacy, analyses should be refined further to exclude patients who have previously exhibited cellular resistance to irinotecan. The chemosensitivity to irinotecan therapy is affected by both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors [46, 47]. The wide heterogeneity in response rates to SG may be attributed to the interindividual variability in systemic exposure to SN-38, despite its improved pharmacokinetics and Trop-2-targeted design [48, 49]. Key genetic polymorphisms in the UGT1A1 gene, UGT1A1*28 and UGT1A1*6 have strong clinical implications such that they result in a reduction of UGT1A1 glucuronidation activity and alter drug disposition of irinotecan, necessitating dose reductions due to increased toxicities [50, 51]. Like irinotecan, UGT1A1 genotype testing is recommended prior to initiation of SG [52]. Our analyses demonstrated that incidence of SG-induced severe adverse events (SAE) such as grade 3–4 diarrhea and neutropenia, known to occur more frequently in homozygote carriers of UGT1A1*28 and UGT1A1*6 alleles, differed between patient subgroups with and without UGT1A1 genotype data. Genotype-specific analyses revealed higher incidence of grade 3–4 neutropenia in patients with heterozygous and homozygous variant genotypes versus wild type group. Severe neutropenia occurred in 67% of homozygous carriers versus 44% from wild type and 50% from heterozygous groups respectively (P = 0.05, Supplementary Table 3). This lack of significance may be attributed to the low frequencies of UGT1A1*28 carriers in the studied cohorts and warrants further validation in larger prospective studies. Nevertheless, this finding has potential clinical implications in which a priori testing of UGT1A1 genotype status may help reduce the frequency of irinotecan-associated adverse events and improve tolerability. Safety data from the ASCENT study also affirmed that discontinuation due to treatment-related adverse events was more frequent in homozygous UGT1A1*28 patients versus heterozygous or wild-type patients [22]. Considerations for known frequencies of UGT1A1*28 in certain ethnic populations as well as the influence of other UGT1A1 genetic polymorphisms such as UGT1A1*6 on SN-38 disposition [50, 53] should be incorporated when designing future clinical trials. For example, UGT1A1*6/*6 is significantly correlated with increased SN-38 exposure and occurs at a frequency of 1–5% in Asians and completely absent in Caucasians [50, 53]. Depending on the ethnic makeup of patient cohorts, UGT1A1 genotype testing of additional alleles may be beneficial in delineating the associations of UGT1A1 polymorphisms on SG-induced AEs and its pharmacokinetic parameters.

Albeit being statistically non-significant, incidences of GI-related AEs were observed to be generally higher in non-specific UGT1A1/not-reported studies versus that of studies with UGT1A1 genotype data. Whereas incidences of hematological events neutropenia and febrile neutropenia were higher in studies with UGT1A1 genotype data. These observed dissimilarities could have been attributed by differences in doses administered in both groups where there is a possible dose-dependent relationship between SG dose and free SN-38 concentrations. Previous pharmacokinetic analyses have confirmed that majority of SN-38 molecules (96%) was bound to IgG whereas free SN-38 exposure concentrations was dose-dependent; higher SG doses at 10 mg/kg resulted in higher free SN-38 concentrations compared to that of 8 mg/kg dose [13, 29, 31]. In the non-specific UGT1A1/not-reported group, all studies employed a dose of 10 mg/kg compared to 76% of studies in the UGT1A1 reported group while remaining studies used other doses of 8 mg/kg and 12 mg/kg. Other factors which may affect SN-38 exposure include age and gender whereby elderly patients have reduced hepatic elimination capacity compared to their younger counterparts and females had increased expression of CYP3A4 due to sex-dependent regulation by growth hormone [54, 55].

In addition to sacituzumab govitecan, three other approved ADCs are currently used in solid tumors: trastuzumab emtansine, trastuzumab deruxtecan and enfortumab vedotin. The first two ADCs are conjugated to a microtubule inhibitor and topoisomerase inhibitor respectively and target HER2 receptors in HER2+ breast cancers whereas enfortumab vedotin targets Nectin-4 and is used in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancers [56]. Studies have demonstrated overall good tolerability and improved response with ADCs in heavily pre-treated patients or who have stopped responding to standard of care therapy [57,58,59]. SG has the second highest drug to antibody ratio (DAR) among the four approved ADCs, following trastuzumab deruxtecan which has a DAR of 8. Similar to SG, trastuzumab deruxtecan has a topoisomerase I inhibitor as its cytotoxic payload and is indicated in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Its approval was largely due to its favorable clinical activity, where patients achieved an overall response rate of 60.3% and median duration of response of 14.8 months [57]. SG was notably less efficacious in clinical indications that have been approved in – ORRs ranging from 28.7% to 44.2% in metastatic TNBC, HR + /HER2- breast cancer and urothelial carcinoma [5, 9, 13, 22, 32,33,34].

Our present findings indicate that SG-related hematological and gastrointestinal SAEs are more tolerable compared to that of conventional irinotecan [60], likely due to lower intestinal SN-38 levels despite a higher SN-38 payload. Prevalence of grade 3–4 toxicities such as diarrhea (8.9%), nausea (3.3%), vomiting (2.5%), neutropenia (40.5%) and febrile neutropenia (5.6%) from this present study are in line with that of early phase clinical trials. The overall discontinuation rate of SG was also low at approximately 5% [21], unlike in other approved HER-2 specific ADCs trastuzumab deruxtecan and trastuzumab emtansine, which had over 50% of patients discontinue treatment due to SAEs such as thrombocytopenia, hepatotoxicity, myelosuppression, gastrointestinal toxicities and interstitial lung disease. These AEs have been presumed to be caused by the cytotoxic components of these ADCs [61]. However, direct comparisons of treatment efficacy and adverse events across ADCs should be made with caution due to underlying differences in tumor types, trial designs and patient heterogeneity. Nevertheless, ADCs have shown enormous potential within the targeted therapy space for the treatment of solid tumors and future head-to-head comparative studies with standard of care therapy are urgently sought after.

This study has several limitations that may have led to inadequate result interpretation. The analysis group containing genotype-specified studies had small sample sizes which may contribute to data skewness. Despite contacting the respective authors of the trials, we faced difficulties in obtaining sufficient UGT1A1 genotype information to perform genetic association analyses with incidences of AEs. Head-to-head trial comparisons remain limited in providing crucial information on differences between individual agents, due to a lack of statistical power and the underlying heterogeneity in adverse events associated with each agent. It was assumed that SG-related SAEs were similar to that of conventional irinotecan, which may have limited our investigations to certain AEs.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis of 11 clinical trials of 1578 patients confirms that SG has good clinical activity in most solid tumor types, particularly that of breast and mUC. The heterogeneity in tumor response may be due to differences in tumoral Trop-2 expression, which could signify a prognostic value in Trop-2 testing prior to treatment selection. While these findings also suggest that UGT1A1 genotype testing for dose optimization of SG may not be warranted at present, this conclusion was made with the caveat that insufficient genotype data was available to perform said analyses. Hence, it would be imperative to perform genotype-based dosing studies to clarify its clinical utility.

Responses