A globular protein exhibits rare phase behavior and forms chemically regulated orthogonal condensates in cells

Introduction

Protein self-assembling and phase separation are widely recognized as fundamental mechanisms in the formation of biomolecular condensates and membraneless organelles (MLOs) which are increasingly discovered to play essential roles in a wide range of cellular activities, such as gene transcriptional regulation1,2, chromatin assembly3,4, cellular stress5,6, metabolism regulation7, and cell division8,9. From the perspective of synthetic biology, the construction of artificial cellular compartments with different biological functions such as cascading catalytic scaffolds in microorganisms10,11 or programmable condensates for spatiotemporal control of mammalian gene expression12 is highly attractive. This requires building blocks such as regulatable protein components which exhibit self-assembling and phase behavior and are well accessible to engineering for tethering other proteins or nucleic acids. In order to not or only minimally interfere with the intrinsic processes of host cells, another important requirement for the building blocks and the corresponding MLOs is the orthogonality13. Several other material properties are required such as low cytotoxicity, good responsiveness and reversibility. In fact, building blocks of MLOs fulfilling above requirements are rarely reported.

The most commonly used building blocks for constructing artificial MLOs are intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) or domains, including those derived from natural MLOs14,15,16 and those designed de novo17. IDPs have several advantages in the construction of artificial condensates, such as ease of use and tunable phase behavior18,19,20. However, due to the similarity in molecular grammar of their assembly, there are concerns about their crosstalk with endogenous MLOs and their low orthogonality21. In addition, IDPs are generally considered to be challenging as drug targets22,23, making it difficult to specifically regulate the phase behavior of IDPs with small molecules.

In E. coli, Lipoate-protein ligase A (LplA) is responsible for the lipoylation, an essential post-translational modification of several key enzymes involved in energy, one-carbon and amino acid metabolisms24,25. As a robust enzyme protein, LplA is also used in study of lipoic acid metabolism26,27, in vivo protein labeling28,29 and antibody‐drug bioconjugation30. Previous studies on LplA have shown it to be a well-folded monomeric globular protein with a molecular weight of 38 kDa24,31. In this study, we report the discovery and characterization of material properties of E. coli LplA, which exhibits structural self-assembly and rare LCST-type phase behavior in vitro and forms small-molecule regulatable orthogonal condensates in both E. coli and human cells. These discoveries provide an enhanced understanding of protein phase behavior and open additional avenues for designing orthogonal and chemically regulatable condensates with potential applications in synthetic biology and cellular engineering.

Results

E. coli LplA undergoes reversible LCST phase separation in vitro

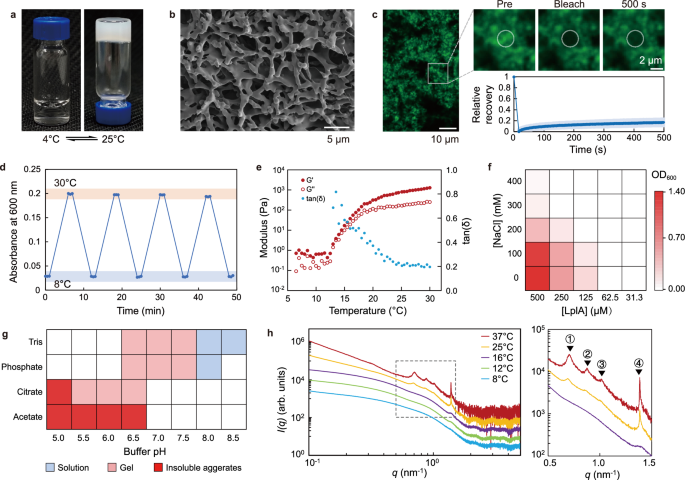

During purification and characterization of its function in lipoylation of GcvH protein26, we unexpectedly discovered that LplA can undergo reversible sol-gel phase transition in vitro (Fig. 1a). LplA was expressed in E. coli using a His-tag, isolated and concentrated to 500 μM (approximately 20 mg/mL) in a 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) buffer. At 4 °C, the LplA solution exhibits good solubility and dispersion with a clear appearance (Fig. 1a). However, as the temperature increases, the LplA solution shows increased turbidity, suggesting the occurrence of microphase separation, and eventually transformed into a self-supporting hydrogel at room temperature (Fig. 1a). SEM image reveals the formation of micrometer-scale aggregates and a porous cross-linked network (Fig. 1b), a typical microstructure of hydrogels. FRAP testing of purified LplA-mEGFP aggregates further demonstrated that they are low dynamic gel (Fig. 1c). Remarkably, LplA exhibits good reversibility in rapid sol-gel cycles (Fig. 1d), without observed formation of insoluble particles or precipitation. Moreover, the catalytic activity of LplA remains unaffected even after repeated sol-gel transition (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a LplA at a concentration of 500 μM undergoes LCST-type sol-gel phase transition in vitro. b Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of LplA gel network. The image is representative of three independent experiments. c Normalized FRAP analysis of LplA-mEGFP condensates in a Tris buffer (pH 7.4) with 100 mM NaCl and 10% Dextran 70. Images are representative of two independent experiments. FRAP data are expressed as the mean ±s.d. for n = 5 condensates. d The thermo-responsive sol-gel reversible cycle of LplA characterized using turbidity at 600 nm. Data are representative of three independent experiments. e Rheological characterization of LplA hydrogel in temperature sweep mode. LplA sample is prepared in a Tris buffer (pH 7.4) with a protein concentration at 1 mM. Temperature sweeps were performed at 1.25 rad/s frequency and 0.1% strain. Data are representative of three independent experiments. f Phase diagrams of LplA at varying salt and protein concentrations in the absence of crowding agents. 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4) was used for solution buffering. Phase separation is determined using turbidity at 600 nm (at 30 °C). Data are representative of two independent experiments. g A summary of the phase behavior at room temperature of 1 mM LplA under different solution conditions. Data are representative of two independent experiments. h Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) profiles of LplA at a concentration of 500 μM in a Tris buffer at different temperatures. Curves were shifted for clarity. The details of the correlation peaks (indicated by the dashed box in the left image) are displayed in the right image. The characteristic distances of the labeled peaks are ① 8.92 nm, ② 7.20 nm, ③ 6.16 nm and ④ 4.55 nm. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

For folded proteins, aggregation resulting from unfolding (or partial unfolding) is commonly observed32. In order to investigate whether LplA undergoes unfolding as temperature increases, circular dichroism spectrum of LplA solution was measured. No significant change was observed in the secondary structure of LplA as the temperature increased (Supplementary Fig. 2). Previous study suggested that His-tag and metal ions may be involved in protein assembly33. Here, we used thrombin to remove the His-tag and found that LplA is still able to form hydrogel (Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating that the self-assembling of LplA is not dependent on the presence of the His-tag. Taken together, these results demonstrate that LplA can undergo homotypic oligomerization and reversible sol-gel phase transition under non-denaturing conditions.

It is worth noting that the phase behavior with lower critical solution temperature (LCST) exhibited by LplA is rare in proteins (especially folded proteins), as most of them have upper critical solution temperature (UCST)34 behavior. In recent years, elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) with VPGXG repeat sequences have been studied as a model system for LCST-type protein phase behavior35. As a well-folded globular protein, LplA has distinct sequences and structures that differ significantly from ELPs. Therefore, LplA represents a folded protein for studying LCST phase behavior. Rheological experiments showed that the critical temperature for sol-gel transition of LplA is around 13 °C under the given protein concentration and buffer conditions (Fig. 1e). As the temperature rises above 25 °C, the viscoelasticity of the LplA solution increases by three orders of magnitude with tan(δ) tending to 0.2, indicating maturation of the gel (Fig. 1e). The strain sweep in the gel state (at 30 °C) showed that the gel network is relatively fragile (Supplementary Fig. 4), indicating weak intermolecular interactions.

To investigate how physicochemical parameters affect the phase behavior of LplA, we determined the phase diagram of LplA. In general, protein phase separation is favored by low ionic strength and high protein concentrations. Consistent with this understanding, we observed that the turbidity of the LplA solution decreases with increasing salt (NaCl) concentration and decreasing LplA concentration (Fig. 1f). The critical concentration of LplA is estimated around 100 μM base on the phase diagram (in the absence crowding agents) at the low salt concentration range of 0~100 mM NaCl (Fig. 1f). The phase behavior of LplA is pH-dependent and, moreover, varies in the four commonly used buffers (Tris, phosphate, citrate and acetate). While no phase separation of LplA can be observed at pH higher than 7.5, LplA undergoes sol-gel transition with reduced pH and even irreversible aggregation at pH lower than 5.5 or in acetate buffer (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 5). The sensitivity of phase behavior to solution environment (salt and pH) suggests that electrostatic interactions may contribute to LplA self-assembling.

To investigate whether the phase separation of LplA is structured at molecular scale, we characterized the phase separation process of LplA at different concentrations using Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) (Fig. 1h, Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). SAXS curves of a 100 μM LplA sample at 8 °C to 16 °C reveal that LplA predominantly exists as monomer in solution, as also indicated by the estimated molecular weight (Supplementary Figs 6c−h). The distribution function P(r) and Kratky plot both exhibits bell-shaped curves, indicating that the monomeric form of LplA protein has an approximate ellipsoidal shape and is well-folded (Supplementary Fig. 6f, g). From 14 °C onwards, the sample starts to change its structure. The forward scattering increases, revealing the formation of larger particles in the solution (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). In high concentration samples (500 μM and 1 mM), distinct peaks appear and evolve in the SAXS curves from 25 °C on to 37 °C, reflecting ordered structures at the oligomer level (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 6b). Specifically, peak #4 (at 4.5 nm) is significantly sharper than the other three peaks and begins to develop at 12-16 °C (during the early stage of gel formation) (Fig. 1h). This likely represents a more stable and specific lower-order assembly that plays a crucial role in the initial nucleation of phase separation. The other three peaks (#1, #2, and #3) start to appear and develop from 25 °C and appear to exhibit some degree of synergy. The larger peak widths and characteristic distances suggest that they may represent higher-order assemblies with weaker specificity, such as those dominated by hydrophobic interactions. In addition, these characteristic distances do not shift with temperature, indicating that these ordered structures have been stable from the early stage of their formation.

LplA forms concentration-dependent condensates in E. coli

Given the self-assembling and phase separation abilities exhibited by LplA in vitro, we asked whether phase separation of LplA also takes place in living cells. We first checked the phase behavior of endogenous LplA in E. coli. Here, mEGFP was used to label the gene lplA on the genome of E. coli MG1655 (Fig. 2a). It was shown that endogenous LplA is uniformly distributed in the cytoplasm and the fluorescent signal is weak (Fig. 2a). No phase separation of LplA was observed even under various cellular stress conditions (Fig. 2a). It has been reported that the endogenous abundance of LplA in E. coli is very low24. Additionally, the transcriptional level of lplA does not exhibit significant changes in response to different cultivation conditions and cellular stress36,37.Therefore, it’s reasonable that the concentration of endogenous LplA within the cell is normally below the critical threshold required for phase separation.

a Confocal images of mEGFP-labeled endogenous LplA in E. coli MG1655 under various cellular stress conditions. Scale bars, 5 μm. Images are representative of three biological replicates. b The overexpressed LplA in E. coli BL21(DE3) formed pole-distributed condensates, with 1,6-hexanediol being able to dissolve the condensates to certain extent. Scale bars, 5 μm. c Quantification of percent protein in condensates in experiment shown in (b). Data are expressed as the mean ±s.d. for for n = 5 cells from three independent experiments. d Normalized FRAP analysis of LplA- mEGFP condensates in E. coli. Data are expressed as the mean ±s.d. for data (n = 6 cells) from three independent experiments. Scale bars, 5 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, we investigated whether overexpressed LplA in E. coli undergoes phase separation. Given the potential influence of steric hindrance resulting from the fusion of fluorescent proteins, the oligomerization of LplA was evaluated by assessing the fusion of mEGFP at either the N- or C-terminus of LplA. After induction for 2 h, both LplA-mEGFP and mEGFP-LplA were observed to form foci in E. coli exhibiting a cell pole distribution (Fig. 2b), attributed to nucleoid exclusion38. The proportion of LplA-mEGFP in the foci (82 ± 3%) was slightly higher than that of mEGFP-LplA (65 ± 6%) (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, in the process of overexpression and purification of LplA, we observed that LplA exhibits good solubility and is predominantly present in the supernatant of the cell lysate. Therefore, it is likely that LplA forms condensates through phase separation in cells rather than forms insoluble inclusion bodies which are usually distributed in the precipitate of cell lysate. This is confirmed by a treatment with 1,6-hexanediol. It has been demonstrated that 1,6-hexanediol disrupts weak hydrophobic interactions of proteins, leading to the dissolution of protein condensates, while it is unable to dissolve aggregates and inclusion bodies driven by strong hydrophobic interactions39. After treatment with 10% (w/v) 1,6-hexanediol for 10 min, both LplA-mEGFP and mEGFP-LplA foci showed significant dissolution (Fig. 2b). The FRAP assay on LplA-mEGFP foci showed almost no recovery, which is even less dynamic than in vitro (Fig. 2d). However, there are cases demonstrating that some highly dynamic condensates observed to undergo liquid-liquid phase separation in vitro can exhibit significant reduced FRAP recovery in E. coli10,40. This phenomenon may be attributed to the technical limitations of FRAP in small volume cells, and it could also be related to the interactions of these proteins with the cellular environment.

We also investigated whether the phase behavior of LplA in E. coli cells remains temperature-sensitive. However, after cold shock or heat shock treatment to the cells, no significant dissolution of the LplA foci was observed (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Considering the macromolecular crowding effect in cells, we added various crowding agents to purified LplA solutions in vitro to simulate the crowded cellular environment (Supplementary Fig. 7b). We found that the presence of Dextran 10, Dextran 70, and Ficoll 400 shifted the phase transition temperature of LplA toward lower temperatures. The addition of PEG directly induced phase separation of LplA at 4 °C , with the extent of phase separation increasing with the molecular weight of PEG (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Moreover, no temperature-dependent changes in the degree of phase separation were observed across the tested temperature range (4–37 °C). Therefore, macromolecular crowding effects are likely one of the key factors causing LplA to lose its temperature sensitivity in vivo.

Molecular basis of LplA assembling and phase separation

Weak multivalent interactions have been demonstrated to be the fundamental driving force for the formation of biomolecular condensates. To reveal the molecular mechanism driving the assembling and phase separation of LplA, we investigated the potential homotypic interaction hot spots on the protein surface. The crystal structure of ligand-free LplA was resolved by Fujiwara et al.31 (PDB ID: 1X2G). The crystal structure revealed that LplA is a well-folded globular protein with no large disordered regions. Although LplA appears to form trimers in the asymmetric unit of the crystal (Fig. 3a), the authors attribute this assembly to the result of crystal packing based on gel filtration experiments31. In this work, we found that the self-assembling of LplA is actually concentration and environment-dependent, and SAXS data provide evidence for the structured oligomerization of LplA. Therefore, we believe that the trimeric arrangement of LplA in the crystal structure reflects a potential pattern of LplA homotypic oligomerization. In the LplA crystal structure, MolA contacts with MolB and MolC in two different ways and forms symmetric dimers (MolA-MolB and MolA-MolC), respectively (Fig. 3a). PISA analysis41 suggested that dimer MolA-MolC is stable in solution, while dimer MolA-MolB is unstable (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Employing ClusPro Dimer Classification42, a molecular docking-based approach, yields similar outcomes (Supplementary Fig. 8b). The MolA-MolC interface exhibits a dense salt bridge network involving 10 charged residues (Supplementary Table 1). Conversely, the MolA-MolB interface possesses fewer charged residues and exhibits exposed hydrophobic patches that involve 4 aromatic residues (Supplementary Table 2).

a The asymmetric unit of the LplA crystal (PDB ID: 1X2G) consists of three LplA molecules (MolA, MolB and MolC). b–i The phase behavior of LplA in E. coli with various single-site mutations. Scale bars, 2 μm. Images are representative of three biological replicates. j Interaction interfaces involved in LplA self-assembly. The contact interface in the crystal structure 1X2G (distance <4 Å) is marked in magenta (left). The mutation sites that lead to complete disruption and weakening of LplA condensation are marked respectively in red and orange (right), the same marking color in Supplementary Table 3, 4. k A diagram illustrating the structural oligomerization of LplA through two types of interface interactions, which is the molecular basis for its phase behavior.

We utilized single-site mutation to investigate whether these two interfaces contribute to phase separation (Supplementary Table 3). Here, we classify the impact of mutations on phase separation into three levels: complete disruption of phase separation, weakened phase separation, and no impact. Complete disruption of phase separation is defined as the absence of detectable focus formation. Weakened phase separation and no impact are determined based on the levels of bulk LplA in cells (({I}_{{bulk}}/{I}_{{bg}})) (Supplementary Fig. 9). Firstly, we individually mutated all the charged residues on the MolA-MolC interface to residues with opposite charges, aimed at disrupting potential salt bridge formation. We observed that a total of 9 mutated charged residues indeed completely abolish the phase separation ability of LplA in E. coli (Fig. 3b). These 9 sites align well with residues involved in salt bridge formation, as indicated by PISA analysis (Supplementary Table 1), highlighted the significant contribution of salt bridge formation to phase separation of LplA. Among the charged residues that do not directly participate in the formation of salt bridges in the crystal structure, we found that mutations of R140, E233, and R303 weaken the phase separation ability of LplA and increase its saturation concentration (Fig. 3c), while mutations of E21, K143, E320, and E322 have no significant impact on LplA condensation (Fig. 3d). These latter four residues are obviously not involved in the formation of salt bridges on the MolA-MolC interface (as shown in Supplementary Table 3) and thus contribute little to the formation of the interface. We also mutated several non-charged residues with polar side chain located in the core region of the interface by replacing them with alanine. Among these mutations, the mutations of aromatic residues H274 and W243 disrupt the condensation of LplA (Fig. 3e), while mutations of non-aromatic polar residues (Q298, Q308, and Q309) have no effect (Fig. 3f). It is known that aromatic side chains provide a driving force for protein phase separation43, as they are involved in π-π packing, cation-π, and hydrophobic interactions. These results suggest that the MolA-MolC interface, as an interaction hot spot region with a dense distribution of charged and aromatic residues, plays an essential role in the phase separation of LplA (Fig. 3j).

Next, we used the same strategy to mutate all the charged and aromatic residues on the MolA-MolB interface (Supplementary Table 4). We found that mutations of D12 and E61 disrupt the formation of condensates, and mutation of R66 increases the saturation concentration (Fig. 3g). Five aromatic residues on the interface were individually mutated to alanine. The mutant W241A fails to form condensate, and the mutations of Y52 and F235 increase the saturation concentration (Fig. 3h). Since interactions caused by hydrophobic patches are non-directional, the assembly involved in this interface is likely to be less structure-specific. The molecular docking results obtained from ClusPro also suggest the possibility of multiple alternative assembly modes on this interface (Supplementary Fig. 8c).

We employed MaSIF-site44 to investigate whether there are other potential interaction hot spots on the surface of LplA. However, apart from the two validated interfaces and the two substrate binding pockets, no additional interaction hot spot was identified (Supplementary Fig. 8d). We also randomly mutated several charged and aromatic hydrophobic residues on the surface of LplA, but no significant effect on LplA condensation was observed (Fig. 3i, Supplementary Table 5). In summary, we have identified the interaction hot spots and key residues that support the multivalent homotypic interactions of LplA (Fig. 3j). We also found that the higher-order assembly of LplA is achieved by two distinct dimerizations, one with clear directionality dominated by electrostatic interaction, and the other is less structure-specific involving both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions (Fig. 3k).

LplA phase separation is specifically regulated by lipoate

Artificial condensates regulated by specific small molecules are attractive for cellular engineering and synthetic biology. In E. coli, LplA is naturally responsible for the ATP-dependent lipoylation of target proteins utilizing exogenous lipoic acid45. The crystal structure of LplA reveals its two inherent substrate binding pockets, which bind ATP and lipoic acid31,46. Consequently, we investigated the impact of these two natural substrate molecules on the self-assembly of LplA. Surprisingly, both (R)-lipoic acid and (R/S)-lipoic acid inhibit the phase separation of purified LplA in minutes, whereas ATP has no effect (Fig. 4a, b). In the analogs of lipoic acid, (R/S)-lipoamide exhibits a similar inhibition, while octanoic acid, octanamide, and 1,3-propanedithiol are ineffective (Fig. 4a, b). The difference between the small molecules in their regulating effect prompted us to correlate it with their binding stability to LplA. Octanoic acid is not a natural substrate of LplA and thus has a Km value (200 μM)47 significantly higher than lipoic acid (4.5 μM)31. We compared the binding constants of these molecules to LplA using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and the results revealed that both (R)-lipoic acid and (R/S)-lipoamide significantly bind to LplA, with Kd values of 22.4 μM and 27.7 μM, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 10a). Conversely, octanoic acid didn’t show obvious binding, consistent with those enzymatic data. Next, we tested the regulation of LplA condensates in E. coli using lipoic acid and lipoamide. At a concentration of 1 mM (the highest concentration tested), both lipoic acid and lipoamide are able to dissolve the LplA condensates. Octanoic acid, octanamide and 1,3-propanedithiol are ineffective, consistent with the in vitro experiments (Fig. 4b). In order to further explore the necessity of specific binding of small molecules to destroy the phase separation, we mutated the “gatekeeper” residues of the lipoic acid binding pocket of LplA (Supplementary Fig. 10b) into residues with larger steric hindrance to disrupt the binding. These mutants did not affect their ability to form foci in E. coli, but they lost their responsiveness to lipoic acid (Supplementary Fig. 10c). These results indicate that lipoic acid inhibits phase separation by binding to the LplA substrate pocket, rather than by directly interfering with interfacial interactions. The crystal structures of LplA have revealed that the C-terminal domain of LplA undergoes significant conformational changes in different ligand binding states31,46. Therefore, we hypothesize that the binding of lipoic acid induces destabilization of the protein conformation, leading to disruption of its oligomerization.

a Chemical structures of (R)-lipoic acid (LA, 1) and its analogues: (R/S)-lipoamide (LM, 2), octanoic acid (OA, 3), octanamide (OM, 4), 1,3-propanedithiol (PDT, 5). 1,6-hexanediol (HDO, 6) is used here as a positive control for non-specific destruction of protein condensates. b Phase behavior of purified LplA (500 μM LplA in Tris buffer) in the presence of several small molecules in vitro. Before the turbidity measurement, we performed a 5-min shaking of the samples to ensure homogeneity. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. c Phase behavior of LplA in the presence of several small molecules in E. coli. Scale bars, 5 μm. Images are representative of three biological replicates.

LplA forms orthogonal condensates in mammalian cells

The chemical tunability of LplA condensates prompted us to further explore their applicability in mammalian cells. In U2OS cell line, mEGFP-LplA was found to form condensates, with no more than 50% of LplA distributed in the condensate (Fig. 5a). Treatment with 1,6-hexanediol significantly dissolved LplA condensates (Supplementary Fig. 11), indicating that LplA condensates might be dynamic gels. Then we examined the dynamics of LplA condensates in cells using FRAP, and mEGFP-LplA condensates showed a recovery rate close to 50% (Fig. 5b). The dynamics of LplA condensates in U2OS cells were significantly higher than that in vitro and in E. coli cells. This suggests that the LplA condensate in cells is not assembled by pure LplA proteins but also with other host proteins inside to regulate the material properties. In addition, under the effect of interfacial tension, biomolecular condensates with high dynamic properties often exhibit smooth phase interfaces and tend to be spherical48. Unlike the gel-like network structures formed in vitro (Fig. 1b, c), LplA condensates in U2OS cells appear as ellipsoids (Fig. 5a), reflecting their highly dynamic property.

a Confocal image of mEGFP-LplA condensates in U2OS cell line (left) and quantification of percentage of protein in condensates (right). Scale bars, 10 μm. The data are expressed in violin plot for n = 68 cells from three independent experiments, where the solid line represent the median and the dashed lines represent interquartile range. b Normalized FRAP analysis of mEGFP-LplA condensates. Data are expressed as the mean ±s.d. for n = 5 condensates from two independent experiments. Scale bars, 5 μm. c–e Representative immunofluorescence images of various subcellular structures suggesting the independence of LplA condensates. Scale bars, 10 μm. Images are representative of three biological replicates. f LplA foci gradually dissolved in the cells under the treatment of 100 μM (R)-Lipoic acid (orange). Scale bars, 10 μm. Data are expressed as the mean ±s.d. for n = 5 condensates from two independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In order to explore the independence of LplA condensate in cells and its orthogonality with other cellular structures, we first investigated the subcellular localization of LplA using immunofluorescence imaging. We labeled the cells with biomarkers for membranous organelles, including the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), lysosomes, mitochondria, and autophagosomes. We found that LplA doesn’t colocalize with these organelles (Fig. 5c). Stress granules and P-bodies are membraneless organelles extensively studied in the cytoplasm, formed through phase separation of proteins and RNA49. We observed that LplA does not colocalize with these two membraneless structures (Fig. 5d). These findings suggest the orthogonality of LplA condensates in the cytoplasm.

Protein quality control is an important biological process in cells that helps maintain protein homeostasis. It is responsible for recognizing and clearing pathological protein aggregates, which are cytotoxic and associated with diseases50. We found that LplA doesn’t colocalize with the protein aggregates markers Hsp70 and Vimentin (Fig. 5e), indicating that LplA foci are not recognized as insoluble protein aggregates within the cell. In contrast, we observed that some ubiquitin and p62 molecules locate inside the LplA condensates, but not completely co-localize (Fig. 5e). We speculate that this may be attributed to the permeability of the LplA condensates, allowing the presence of certain cellular components entering them.

We then investigated whether LplA condensates in U2OS cells could respond to lipoic acid and lipoamide. After 1 h of treatment with 100 μM lipoic acid, a significant reduction in the volume of LplA foci was observed in the cells (Fig. 5f). Furthermore, we conducted long-term observations of living cells treated with various concentrations of the lipoic acid and lipoamide to obtain more detailed information across a broader concentration range and time scale (Supplementary Fig. 12). From the foci number, we observed that with increasing lipoic acid (or lipoamide) concentration, the foci dissolved more quickly. Under 100 μM lipoic acid or lipoamide treatment, the half-life of the foci numbers were 1 h and 0.7 h, respectively. On the other hand, the rate of reduction in the size of the foci was also drug concentration-dependent. Significant size differences could be observed within 2 h under 100 mM lipoic acid or lipoamide treatment. Overall, the response speed of LplA foci to lipoic acid and lipoamide was slower than in vitro and in E. coli cells, which may involve multiple influencing factors, including foci size, diffusion rate, and differences in the foci composition, etc. The LplA foci in E. coli are much smaller (diameter 100–500 nm) than in U2OS cells (diameter 1–5 μm). It is reasonable that larger foci require longer dissolution times. Due to differences in membrane permeability and specific surface area of the cells, the time for small molecules to reach the foci from the extracellular space may also differ. Moreover, we speculate that there are other proteins involved in the assembly of LplA foci in cells (Fig. 5e), and these unknown components may affect the dissolution rate of the foci to some extent.

Discussion

LplA from E. coli is a well-folded globular enzymatic protein found to exhibit rare LCST phase behavior in vitro and to form chemically regulatable orthogonal condensates in vivo in both bacterial and mammalian cells. In vitro LplA can form gel-like condensates or hydrogels in a non-denatured state. In condensates biochemistry, LCST-type phase behavior is rare in proteins and not known for folded proteins, while UCST-type phase behavior is more common34. Elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) are currently used as model systems to study LCST-type protein phase behavior35. However, the molecular mechanism of LplA phase separation differs fundamentally from that of ELPs. Structure-based point mutation screening revealed that the self-assembly of LplA has well-defined contact interfaces with a high abundance of charged residues, suggesting the dominant role of electrostatic interactions. Notably, we also found some small hydrophobic patterns on the interaction interface, which may be beneficial to the establishment of LCST-type thermo-responsiveness due to their negative contribution to the mixing entropy ((varDelta {S}_{m})) and mixing enthalpy ((varDelta {H}_{m}))51. Compared with IDRs, the lower conformational entropy change of globular LplA molecule may also contribute to its LCST-type thermo-responsiveness. Although the theoretical explanations for LCST and UCST phase behaviors have been elucidated in the study of synthetic polymers51, there are still challenges in understanding the thermal responsiveness of biological macromolecules from a thermodynamic perspective. Therefore, the discovery of LplA’s LCST-type phase behavior in vitro expands our current understanding of protein self-assembling and phase behavior in aqueous solutions and gives hints for designing LCST self-assembling proteins.

LplA has been shown to be of great importance for one-carbon and energy metabolisms in vivo. It has an indispensable role in post-translational modification of H-protein of the glycine cleavage system and acyltransferase subunit (E2) of the α-keto-acid dehydrogenase multi-enzyme complexes25. Thus, the catalytic activity of LplA condensate makes it a potential candidate as tissue regeneration material and biosensor in vivo. In addition, LplA is also a robust enzyme that has broad substrate specificity and has become a very useful tool for applications using in vivo protein labeling with fluorophores28,29. Previously, LplA was engineered for site-specific antibody conjugates for sequential and orthogonal drug delivery and release30. Coupling the biological functions mentioned above with the phase behavior of LplA could open up hereto unthinkable or other applications of this unusual protein.

It is of particular interest to examine if LplA can be used to realize phase transition inside cells or tissues. We showed that in both E. coli and U2OS cells LplA forms stable gel-like condensates that spatially coexist independently of membranous and non-membranous cellular compartments. These results suggest that LplA has great potential as an orthogonal building block for creating artificial membraneless organelles using a catalytically active protein instead of disordered proteins as presently dominated. For example, we have recently successfully used LplA as a building block to develop chemically programmed nuclear condensates for spatiotemporal control of mammalian gene expression at different stages of interest and at different cellular localization12.

In this context, it is worth noting that the self-assembly and phase separation of LplA can be specifically suppressed by its natural substrate, the small molecule lipoic acid (and its analog lipoamide). This could be due to the disruption of protein conformational stability induced by lipoic acid binding to the substrate pocket of LplA. This may propose a strategy for small molecule regulation of biological condensates. Moreover, the biocompatibility of lipoic acid has been proven in clinical studies over the past decades52. Therefore, LplA condensates regulated by lipoic acid hold broad prospects in the field of biomedical research.

The discovery of the phase behavior of LplA is a lucky case by-chance. We notice that “unexpected” phase behavior of proteins (such as liquid-like and gel-like phase separation) in in vitro experiments may have been largely overlooked in the past, because these phenomena are easily mistaken as protein sample deterioration and thus escape attention. This may have led to missed opportunities to discover well-folded globular proteins with phase behavior and knowledge related to protein oligomerization and phase separation, including protein assembly regulated by temperature, solution environment, and small molecules, all of which are of great interest to researchers in the field of biomolecular condensates. In the vast protein universe, there are likely still a considerable number of proteins, especially well-folded proteins, that have the ability to self-assemble and undergo phase separation but have not been explored. A recent study on structuromics has shown that in a proteome of an archaeon or E. coli, approximately 45% of the proteins can form homomers, with surprisingly more than 90% being symmetric aggregates53. Another study also suggests that the supramolecular assembly of folded proteins in E. coli is frequently sampled by evolution54. Therefore, we believe that the discovery and characterization of LplA phase behavior reported in this work could spark interest in screening in natural proteomes for well-folded proteins with the ability of homomeric oligomerization, which will, in turn, advance the fields of protein phase separation and biomolecular condensates.

Methods

LplA purification and storage

The gene encoding E. coli LplA was synthesized by GenScript (Nanjing) and inserted in pET-28a(+) vectors by In-fusion cloning. LplA with a C-terminal His-tag was expressed and purified from E. coli strain BL21(DE3). Specifically, Recombinant cells were incubated at 37 °C in LB medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin until the OD600 reached about 0.6, and 0.2 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added to induce protein expression for 12 h at 30 °C. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 15 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (500 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.5) and lysed by high-pressure homogenization. The lysed samples were subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were loaded onto a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) using an ÄKTA pure system (GE Healthcare). Following an appropriate washing process, the target protein was eluted using an elution buffer (500 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 7.5). Purified proteins were dialyzed against a storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) using a 30k MWCO spin filter (Millipore). Protein concentration was determined using BCA assay, and the protein purity was tested using SDS-PAGE. Aliquots of purified proteins were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Reagents and materials used in this work are shown in Supplementary Table 6. Plasmids and primers used in this study are shown in Supplementary Tables 7, 8.

Turbidity assay and circular dichroism spectroscopy

Turbidity is utilized to assess the degree of phase separation of LplA in phase diagram plotting and small molecule responsiveness assays. LplA samples were loaded into a 96-well plate (100 μL per well), and the turbidity was measured at 600 nm at a temperature of 25 °C using a plate reader (Spark, Tecan). The turbidity in sol-gel cycling experiment and the circular dichroism spectroscopy of LplA were determined in a 0.5 mm pathlength cuvette using the Circular Dichroism Spectrometer V100 with a temperature control module. In sol-gel cycling experiment, 500 μM LplA in storage buffer were equilibrated for 5 min at each temperature, and the assay was repeated three times (30 s interval between each time). In circular dichroism assay, 2 μM LplA in a phosphate buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate, 100 mM (NH4)2SO4, pH 7.2) were equilibrated for 5 min at each temperature before tested.

Rheology

The rheological properties of the LplA sample were measured at different temperatures using a rotational rheometer (AR2000ex, TA Instruments). The LplA samples were prepared in an ice-cold storage buffer with a concentration of 1.0 mM. Anti-volatile rings were applied to prevent solvent evaporative loss from the sample during the measurements. Temperature sweeps were performed at 1.25 rad/s frequency and 0.1% strain. Data sampling is conducted at intervals of 0.5 °C, ranging from 6 to 30 °C, with a 20 s equilibrium at each temperature point.

Scanning electron microscopy

1 mM purified LplA in a 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) were first incubated at 37 °C for 5 min, and then flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen to preserve its microstructure. After overnight freeze-drying, the sample was carefully transferred onto sample stage covered with carbon adhesive, and sputtered with gold for 60 s. Imaging was performed on a GeminiSEM 450 (Zeiss).

Small angle X-ray scattering

SAXS measurements were performed at the BioSAXS beamline P12, EMBL/DESY, Hamburg, Germany (Blanchet et al. 2015) using the 150 µm (v) × 250 µm (h) beam at an X-ray energy of E = 10 keV (wavelength λ = 0.124 nm). Sample solutions were automatically loaded into an in vacuum quartz capillary (inner diameter: 1.7 mm (first session); 0.9 mm (second session)55) using the robotic P12 sample changer56 with continuous sample flow during data collection.

The measurements were performed over a temperature range from 8 °C to 40 °C. For each temperature point, sample and buffer were freshly loaded to avoid beam-induced radiation damage. Two-dimensional SAXS patterns were recorded using a PILATUS 6 M pixel detector at a sample-detector-distance of 3 m, covering the range of momentum transfer s = 0.04–7.0 nm−1 (s = 4π/λ sin(Θ), where 2Θ is the scattering angle). SAXS data were recorded as a sequential set of 40 images for every 100 ms of exposure. Information on samples and data acquisition can be found in the Supplementary Table 9 and Supplementary Fig. 6h.

The recorded SAXS patterns were azimuthally averaged (masking inter-module segments of the detector as well as the shadows of the beam stop and the flight tube), normalized to the transmitted beam, checked for the absence of radiation damage, averaged accordingly, and the scattering signal from the corresponding buffers was subtracted from the 1D-SAXS profiles of the proteins, all done by the P12 beamline SASFLOW pipeline57. The resulting difference curves were further analyzed using the ATSAS software package58.

Imaging of endogenous LplA in E. coli

The E. coli strain MG1655 Φ(lplA-mEGFP) was constructed to investigate the subcellular behavior of endogenous LplA in bacteria. We employed the CRISPR/Cas9 system to knock in the mEGFP downstream of the lplA gene in the wild-type E. coli MG1655 genome. Gene editing was conducted following the method described by Zhao et al.59. The strain validated through colony PCR was cultured at 37 °C for 6 h and the cells were diluted with LB medium to an OD at 600 nm of 0.2. Before imaging, we induced cellular stress by manipulating the culture temperature or adding specific reagents. Images were acquired at room temperature using an LSM980 laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss) with a 63×/1.4 oil immersion objective.

Imaging of overexpressed LplA and mutants in E. coli

Two versions of fusion genes (lplA-mEGFP and mEGFP-lplA), which were used for imaging in E. coli, were constructed in pET-28a(+) vectors by In-fusion cloning. Single-site mutation of LplA were performed using a Mut Express II Fast Mutagenesis kit V2 (Vazyme) and sequenced by Sanger sequencing (Tsingke). The primers used for point mutations are shown in Supplementary Table 8. Plasmids with gene of interests were transformed into BL21(DE3) (Tsingke) cells, which were plated on plates with kanamycin resistance and grown overnight. A single colony was picked and cultured in 5 ml of LB medium with 50 mg/mL kanamycin. After 6 h at 37 °C (at 220 rpm), the cells were diluted to an OD at 600 nm of 0.2 with LB medium and induced with 0.2 mM IPTG. After 1 h at 37 °C (at 220 rpm), centrifuge and resuspend the cells in PBS, adding the small molecules to be tested. Imaging and FRAP experiments were performed at room temperature using an IX73 inverted microscope (Olympus) with a 100×/1.4 oil immersion objective.

U2OS stable cell line

HEK293T and U2OS cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (PAN Seratech) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. U2OS cells stably expressing mEGFP-LplA were generated by lentiviral transduction of a pCDH-mEGFP-LplA plasmid. To construct pCDH-mEGFP-LplA plasmid, mEGFP fragment amplified from mEGFP-C1 plasmid (Addgene, 54759) and LplA fragment amplified from pET28a-LplA plasmid were inserted into pCDH-CMV (Addgene, 72265) backbone using Takara In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit. The lentivirus was prepared in HEK293 cells, plated at 1 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well dish. Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for transfections according to manufacturer’s instructions. 24 and 48 h after transduction the virus was collected, filtered, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C. Different concentrations of viruses were tittered on U2OS cells.

Living cells imaging and FRAP measurements

Cells were grown in 35 mm diameter glass bottom cell culture dishes (NEST). mEGFP-LplA condensates were bleached, and fluorescence recovery after bleaching was monitored using ZEN software on an LSM980 laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss) with an incubation chamber at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Data were analyzed in ZEN (Zeiss).

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

The sample for observing stress granules was treated with 1 mM sodium arsenite for 30 min before the fixation. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Science) in PBS for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and then blocked with 1% BSA for 1 h, with all steps performed at room temperature. Samples were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, then washed 3 times with PBST (0.1% Tween) and incubated with host-specific Alexa Fluor 647 secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing 3 times, 1 μg/mL DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Images were captured using an LSM980 laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss) with a 40×0.95 objective and 63×/1.4 oil immersion objective. Images were processed using ZEN (Zeiss).

Long-term live-cell imaging

For long-term live cell imaging with drug treatment, U2OS mEGFP-LplA cells were plated onto Cellvis glass-bottom black 96-well plates (Cat. No. P96-1.5H-N) and cultured to 80 ~ 90% cell confluence. The addition of different concentrations of drugs and imaging were conducted on a CV8000 High Content Imaging System (Yokogawa). Images were acquired using a 20× objective every 30 min after dosing. Three replicate sample wells were set up for each test condition. In each sample well, 6 fixed fields of view were selected for continuous imaging. Image processing and automated foci identification and statistics were done by CellLibrarian software.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry experiments were conducted using a MicroCal PEAQ-ITC instrument to determine the dissociation constants of three different small molecule solutions when titrated into the LplA protein solution. The protein LplA was prepared at a concentration of 50 μM, while the small molecule solutions were prepared at a concentration of 750 μM. Small molecule solutions are prepared using the same buffers as protein solutions (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). The experiments were carried out at a constant temperature of 20 °C. Each small molecule solution was titrated into the protein solution using an 18-injection protocol. Data were collected and analyzed using the Malvern MicroCal PEAQ-ITC Analysis Software (v1.3.0) to calculate the binding affinities.

Protein-protein docking

We used ClusPro web service [https://cluspro.org/dimer_predict] for dimerization docking of LplA. In the “Dimer Classification” mode, we ran the docking of chain A-chain C and chain A-chain B respectively using the publicly available crystal structure 1X2G. The submitted computational tasks are processed by an online computing service provided by the ClusPro team.

Graphs, statistical tests and reproducibility

Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 9 software were used to generate graphs for figures. PyMOL is used for annotation and visualization of protein structures. All box plots in figures show all data points. All experiments cited as independent experiments in legends were biologically independent experiments.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses