Evolution, genetic diversity, and health

Main

Genetic variation in humans is a result of our evolutionary histories and our past and current environments1,2,3. These have led to patterns of shared and distinct genetic variation at different geographical and temporal scales, which have influenced a multitude of traits related to human health and disease4,5,6. To make the benefits of personalized and precision medicine widely available across diverse genetic ancestries and environments, it is crucial that the medical research community adequately captures and contextualizes human genomic diversity, and uses this information responsibly and fairly.

As societies seek to make amends for centuries of colonization—the harms of which are still evident in wide-ranging inequities, including within health and medicine—this topic has never been more relevant7,8,9,10. However, it is important to understand that the scales along which clinically relevant genetic variation might cluster are not uniform, and they are not limited to socially constructed races11. For example, genetic variation introgressed into humans from Neanderthals is relevant for COVID-19 disease severity12, and some genetic variation is relevant for disease risk in only a given group or environment13,14,15,16.

In this Perspective, we examine the importance of diversity in clinical genomics through an evolutionary-history lens. We discuss key advances in the last few decades, including the Pangenome and the growth of global biobanks. We summarize key clinical applications of diverse genetic data in identifying region-specific variation and gene-environment interactions—crucial for understanding disease risk, disease development and drug responses across diverse environmental and ancestral continuums in our complex modern world.

Biomedically relevant human genetic diversity across space and time

All humans across the world share the same origin along with a long history of evolution. Demographic events such as migrations, bottlenecks (that is, a drastic reduction of the size of a group) and population expansions have led to the global genetic diversity that exists today. One example is the Out-of-Africa migration, which caused a bottleneck and decreased the genetic diversity found in humans that populated the rest of the world17. The exposure to different environments has also shaped our genome, leading to the selection of variants that are advantageous in specific contexts18. As environments change, the effects of genetic variants can shift over time. Other evolutionary forces, such as genetic drift (random changes in allele frequency due to small group size) and gene flow (movement of genes in or out of a group), can also influence allele frequencies18. Thus, the distribution of rare and common genetic variation, which provides a blueprint for the development of complex traits and diseases, is a result of the many demographic and selection events that make up our evolutionary history.

Despite the complex demographic history of humans, variable genetic loci constitute only a small fraction of the human genome19. Such variation can be found in the nuclear genome, as well as in the mitochondrial genome (Box 1) in the form of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and structural variants, such as insertions/deletions (Indels), duplications, copy-number variants, inversions, translocations, variable tandem repeats, transposons, endogenous virus sequences and variable telomere length20,21,22. Recently, the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium assumed the monumental task of representing human genetic variation, creating a more accurate representation than ever before, stemming from diverse individuals from around the world23.

Human variation first emerged, and continues to emerge, along temporal and spatial scales, shaped by shared demographic histories. Researchers have highlighted the importance of considering the continuum of genetic ancestries when studying humans24,25. To do this, we should consider multiple time slices that are relevant to biomedical research; for instance, archaic, continental and sub-continental (or modern) ancestries (Fig. 1).

Genomic patterns emerge over time and geographic scales. We illustrate genetic variation over three different time scales and the current geographic distribution. In the blue time slice, we display the geographic distribution of the minor allele of rs35044562 (ref. 145) in a Neanderthal haplotype associated with a higher risk of severe symptoms after COVID-19 infections (map based on Zeberg and Pääbo12). In the yellow time slice, we show a color gradient representing the average total number of short ROHs, which resembles the geographic distance from Africa. The numbers of ROHs in the cohorts were obtained from panel A of Figure S4 in Pemberton et al.146; the map values were estimated by visually inspecting the violin plot’s median values and categorizing them into six ranges on the basis of class A ROHs. Cohorts at the upper extreme of an interval were assigned to that range. In the gray time slice, we visualize the cohort frequency of the rs570553380 variant in individuals from the 1000 Genomes Project (the map was generated with the Geography of Genetic Variants Browser147) as an example of a cohort-specific rare variant (visualized on a scale, or as a proportion, of 0.1)34.

Events such as the introgression of archaic hominins have left a footprint on the modern human genome and continue to influence human health26. Recently, a study described a genomic segment inherited from Neanderthals that is associated with a higher risk of severe COVID-19 symptoms and an increased likelihood of hospitalization due to the disease12 (Fig. 1). In the study, it was hypothesized that this haplotype might have been subject to natural selection in the past. This effect contrasts with another haplotype contributed by Neanderthals, which has been shown to protect against severe COVID-19 (ref. 27).

Another type of genetic variation is known as runs of homozygosity (ROHs), which are continuous homozygous segments of the genome, classified by length as ‘short’ or ‘long.’ ROHs are structured at varying scales, including the continent level. Human migration across the world was accompanied by bottlenecks and reduced effective population sizes in different regions. The groups that went through these demographic events have a larger proportion of their genomes in ROHs28. Short ROHs, inherited from distant common ancestors, show a positive correlation with the geographic distance from East Africa29 (Fig. 1). In agreement, a recent study has shown that the proportion of Indigenous genetic ancestry is positively correlated with the number of small ROHs in individuals in the Mexican Biobank5. ROHs are enriched for homozygous genotypes, regardless of their allele frequency28. However, rare variants show a stronger enrichment than common variants: their probability of appearing in the homozygous state is much higher inside the ROH than in the rest of the genome. ROHs have been associated with multiple complex traits, such as height, body mass index (BMI), triglyceride and glucose levels, and forced expiratory volume5,30. A study of 133 cohorts found a consistent negative association of the fraction of an individual’s genome in ROHs (FROH) with height, across seven continental groups (including Africans)30, although effect sizes varied. In the Mexican Biobank, the total length of ROHs in a genome was similarly found to be significantly associated with shorter height5. By contrast, another study conducted in Himba, an ethnic group in Namibia that has endogamous practices and that recently experienced a bottleneck, showed no significant effect of FROH on height—suggesting variable phenotypic expression from increased homozygosity among human groups31.

The subcontinental scale is also important to consider when studying human genetic diversity. Migrations during the peopling of the Americas, along with group isolation and founder effects (a reduction of genetic diversity when a subset of individuals is separated from a larger group), led to genetic divergence. A study on the demographic history of Indigenous groups in Mexico inferred the split between northern and southern ethnic groups (7,200 years ago) and subsequent local divergence (6,500 and 5,700 years ago)32. The study also found evidence of genes under selection: BCL2L13 in Tarahumara individuals, which has high expression in skeletal muscle, and KBTBD8 in Triqui individuals, which is associated with idiopathic short stature. Furthermore, this study identified more than 4,000 new variants (most of them in individuals or small groups), showing the importance of studying diverse human groups to detect region-specific variants that could have a role in drug response and disease development.

Social practices can also influence genetic patterns. For example, a recent study found evidence of genetic divergence approximately 70 generations (1,200–1,500 years) ago among subgroups in the Bradford Pakistani community in the UK33. The authors concluded that population structure was shaped by the Biraderi social stratification system, leading to non-uniform distributions of genetic variation and disease manifestation. A study using another British Pakistani dataset found that FROH, partially influenced by mating patterns, is associated with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and post-traumatic stress disorder, among other diseases6.

Genetic variants are constantly arising in the human genome and are subject to evolutionary forces such as natural selection. Particular environments, such as high altitudes, can increase the frequency of adaptive alleles, leading to the emergence of region-specific variants. One such recent SNP, rs570553380(G), identified in Andean highlanders, emerged around 9,845 to 13,027 years ago34. This variant has been associated with low hematocrit levels, with male carriers exhibiting higher O2 saturation under hypoxic conditions. The rs570553380(G) variant appears at a very low frequency in publicly available datasets and has been observed only in Peruvian individuals in the 1000 Genomes Project (Fig. 1).

The study of genetic variation across all human groups is important for understanding complex traits and diseases. Without including diverse populations, we will not be able to fully understand the genetic architecture—that is, the ways that genes, environmental factors and their interaction influence a phenotype—of many complex traits and diseases35. If we study only the diversity in a particular geographic region, we might not observe rare variants that exist elsewhere, or if we observe them, they might not be in a useful frequency for statistical analysis36.

As noted, environmental factors play a crucial part in trait manifestation. These factors can include the weather, the amount of minerals found in drinking water, exposure to pathogens, social exposures and the intake of medical drugs. For instance, some drugs do not have the same effect across individuals37. The interactions between FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated) gene variants and lifestyle and environmental factors provide a classic example of gene–environment interaction38. A study has shown that physical activity reduces the impact of FTO risk alleles on BMI, whereas frequent salt addition to food amplifies their effect. However, the effect size of the interaction between physical activity and FTO risk alleles varies across geographic regions39. Including diverse data that capture different geographies, incomes, sexes and habits in such studies allows us to evaluate the effect and interactions of the same variant in different environments and can improve trait-prediction accuracy40.

To make precision medicine universally accessible, we must increase diversity in studies in multiple ways. Beyond genetic ancestries, for example, this includes diversifying datasets in terms of their location (by incorporating diverse rural environments, for example) and across genders and socioeconomic status—all of which will lead us to a better understanding of complex traits and diseases.

Recent advances and challenges in diversifying genomics

In 2023, the first human pangenome reference draft was released23, and biobanks are currently active in more than 40 countries globally (according to the IHCC Cohort Atlas) (Fig. 2). This has been part of a short period of rapid progress, starting in 1987 when the first genetic map provided an initial location of genes and genetic markers in the human genome41. After that, in 1990, the Human Genome Project was launched, with the international goal of sequencing and mapping the entire human genome42.

The figure shows key events from the first human genetic map in 1987 to recent milestones, such as the first draft of the human pangenome in 2023, as well as the expansion of biobanks across the globe. This figure is not exhaustive; a representative sample was chosen to reflect the breadth of recent developments in genomic studies and biobanking.

After the publication of the draft human sequence in 2001 (ref. 43), the first successful genome-wide association studies (GWASs) quickly emerged44,45. GWASs use statistical modeling to assess and quantify the association of genetic markers genome-wide with a disease or trait under study46. In 2002, Ozaki et al. investigated the association between 65,761 SNPs and myocardial infarction, employing a limited sample consisting of 94 individuals with the condition (cases) and 658 controls47. Similarly, in 2005, Klein et al. explored the association of 116,204 SNPs with age-related macular degeneration, with 96 cases and 50 controls48. A number of similar studies were conducted49 until 2007, when the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium executed the first large-scale GWAS, encompassing approximately 2,000 cases for each of seven prevalent diseases and 3,000 controls and analyzing a total of 469,557 SNPs that met quality-control criteria50. This study is regarded as the first optimally designed GWAS51,52.

Subsequent projects, such as the 1000 Genomes Project (ref. 53), along with the establishment of various Biobanks in both the Global North (including the UK, Uppsala and Danish National Biobanks) and Global South (such as the Maule Cohort in Chile and the Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) consortium, among many others), have advanced the collection and analysis of human genome data. The creation of the pangenome and of diverse biobanks are key advances in our understanding of the human genome and its relationship with various phenotypic traits and medical conditions. They also highlight the importance of including diverse data and reinforce the need to prioritize global cooperation in genomic research54. But to be truly useful, analytical capabilities and methodologies must advance in parallel with these initiatives (Box 2).

Pangenome

Reference genomes aid in reconstructing DNA sequences from raw data, analyzing genetic variations to gain insights into human evolutionary patterns and identifying genetic factors involved in diseases to enable development of targeted therapies. Despite efforts to diversify data since the first reference assembly of the human genome in 2001 (ref. 43), about 70% of the GRCh38 reference genome (which was the most up-to-date version until the recent completion of the pangenome) comes from a single individual55.

The creation of the human pangenome introduces a new approach to comprehend and represent human DNA. This framework allows a more inclusive representation of human genetics because it incorporates data from 47 individuals from diverse regions of the world, with 51% of them hailing from Africa—which has substantial genetic diversity23. Furthermore, it encompasses a wide range of genetic variations, including structural variants that are not accounted for in the earlier reference genome (GRCh38).

This enhancement improves the precision in representing genetic diversity that can subsequently be evaluated in GWASs and enables analysis of genetic variants that were not previously analyzable—such as duplications56, translocations57 and variation in centromeres58—all with a potential role in disease development and drug response. Handling this level of complexity requires new data structures, algorithms and graph-based analytical approaches59. For example, the PanGenome Research Tool Kit (PGR-TK) is a software solution designed to provide flexible and scalable representation, visualization and analysis of genomic variation through the use of pangenome graphs60. Nevertheless, integrating the pangenome into genomics will take some time as these approaches are further developed and adopted by researchers. This will present additional challenges in areas with limited technological infrastructure, so key priorities are ensuring that cloud computing platforms are accessible and fostering collaborative sharing of technical expertise across regions. Still, most genetic analyses worldwide are based on linear reference genomes, such as GRCh38 and its past versions59,61. The human pangenome opens the study of new genetic regions and variants, and in time, further research will reveal the role of these understudied regions in understanding human disease and evolutionary history59,62,63.

Global biobanks

Biobanks facilitate GWASs that can map genomic loci linked to various phenotypes and diseases. The UK Biobank is an exemplary model of a diverse, comprehensive, globally available resource, with well-organized phenotype codes and a research access platform for computing and storage. An effort was made to facilitate pooling of biobank data through the Global Biobank Meta-Analysis Initiative (GBMI) consortium, a collaborative network that integrates data from multiple biobanks across the world to enhance the power of genetic discovery in human disease64. The GBMI initially included nine biobanks from North America, eight from Europe, four from East Asia, one from West Asia and one from Oceania. Recently, six more biobanks have been integrated, including one from Africa. By pooling genetic and health-record data from more than two million individuals with different ancestries, the GBMI conducts meta-analyses of GWASs to identify genomic loci associated with a range of diseases and traits. The initiative addresses the under-representation of non-European ancestries in genetic research, aiming to improve risk prediction and the understanding of disease biology, which can inform drug discovery and development65,66.

However, the GBMI faces challenges owing to the heterogeneity in case definitions, recruitment strategies and the multi-ethnic composition of study populations64. These hurdles require careful application of statistical genetics methods and consideration of ancestries and tissue specificity in analyses such as transcriptome-wide association studies. Nevertheless, the GBMI successfully integrates GWAS results from diverse biobanks to discover new genetic loci, with improved risk prediction of some diseases. For example, the meta-analyses of 18 biobanks across 14 diverse endpoints led to the discovery of 183 new loci, including 49 associated with asthma. The use of the generated summary statistics improved asthma prediction accuracy across six ancestral groups, outperforming prediction using a previous meta-analysis conducted by the Trans-National Asthma Genetic Consortium64,67.

A similar approach, but on a smaller scale, is the BioMe Biobank Program—linked to the electronic health records of a diverse group of individuals in New York68. This ongoing initiative has recruited ~60,000 participants from the Mount Sinai Health System in a non-selective manner. On the basis of the analysis of about 32,000 individuals from the BioMe biobank, Belbin et al. found that 1,177 health conditions were associated with a specific genetic community68. The identification of these fine-scale genetic communities proved valuable for understanding the prevalence of Mendelian diseases. Furthermore, the authors analyzed the distribution of polygenic scores (see ‘Polygenic prediction and precision medicine’) for five common diseases in two communities in the same continental group, detected on the basis of their sharing of genomic segments identical-by-decent. They observed significant differences in the mean values of the distributions of all scores between the two communities, highlighting how fine-scale mapping can enhance the understanding of complex diseases and risk prediction.

Along the same lines, the All of Us research program aims to promote diversity and inclusion in genomics and health research69. It currently includes whole-genome sequencing data with matching survey responses and physical measurements for more than 245,000 individuals. Furthermore, it comprises electronic health records for more than 206,100 individuals70 and expects to collect genetic and health data for more than one million people in total across the USA71. Notably, in this study, a large proportion of participants were from under-represented groups in biomedical research70. The research program includes participants from not only diverse ancestry backgrounds, but also sexual and gender minorities, low-income groups, various education levels and a broad age range (18–89 years of age). This approach led to the discovery of 275 million previously unreported genetic variants70.

The All of Us paper70 was critiqued by prominent geneticists, with one of the main figures deemed an inadequate representation of the genetic data and that could perpetuate harmful notions of race72,73,74. This controversy highlights the major challenge of conceptualizing, inferring and visualizing multi-scale human genetic diversity. Dominant methods have historically relied on fixed typological groups75,76; new approaches are needed that embrace relational thinking and genetic continuums, applicable across biobank scales11,77,78,79. This will allow accurate, inclusive genomics research and equitable distribution of the resulting benefits in a world in which the boundaries assumed by fixed typological frameworks (for example, continental groups) continue to blur.

Furthermore, despite many positive efforts, biobanks remain geographically biased toward countries in the Global North54. This bias limits the scope of genomics studies, because even when individuals of diverse ancestries are included, the detailed picture of the ancestry continuum in Global South countries is not captured, nor is the environmental diversity of those regions. This limitation hinders the characterization of biomedically relevant, region-specific variants and the study of gene–environment interactions, relevant for disease development, prognosis and drug response. Recent methodological innovations, such as those by Ni et al.80 and Sadowski et al.81, are promising for disentangling true gene–environment interactions from gene–environment correlations.

In this context, initiatives in Latin America, Asia and Africa have gained more relevance. For example, the Mexican Biobank Project, led by the Cinvestav Research Center and the Mexican National Institute of Public Health, currently comprises genotype data for more than 6,000 individuals, with the potential to expand to 40,000 (ref. 5). In this biobank, most individuals were recruited from rural areas (70% of the published data), 70% are female, and the biobank is enriched for individuals who speak an Indigenous language. The inclusion of different environments led to a better understanding of BMI: living in urban areas was found to be associated with higher BMI, whereas high FROH is associated with low BMI in Mexico5. The Mexico City Prospective Study (MCPS) was developed as a collaboration between the University of Oxford and the National Autonomous University of Mexico and provides genetic and phenotypic data for 140,000 individuals from Mexico City82. The MCPS grants exclusive access to researchers in Mexico for the first two years through the DNA Nexus Research Analysis Cloud Computing Platform, providing an example of a data-sharing protocol that fosters global collaborations while respecting local data sovereignty. Moreover, both the Mexican Biobank and the MCPS have conducted local training workshops in Mexico, prioritizing and boosting local capacity building and technical expertise.

Several important efforts have also been undertaken in Asia and Africa, such as the BioBank Japan (with 200,000 individuals)83, the China Kadoorie Biobank (with 512,000 individuals)84, GenomeAsia 100K Project (with 1,739 whole-genome sequences representing 219 population groups in the pilot phase)85, the Singapore SG10K Project (with 4,810 individuals)86, the Uganda Genome Resource (with genotype data information for 5,000 individuals and whole-genome sequence data for 2,000 individuals)87, and the H3Africa initiative (with 23,421 biospecimens from 35 datasets, according to its Biospecimen Catalogue)88. Although projects are usually national, H3Africa includes more than 30 African countries, GenomeAsia covers 64 countries across Asia, and the SG10K project covers Chinese, Malaysians and Indians from Singapore.

These initiatives share the goal of better understanding the genetic basis of diseases and population diversity by analyzing genetic variation and associations with traits or risk factors. They have identified new variants and unreported genetic loci and elucidated migration patterns and evolutionary processes characteristic of the studied groups. For instance, in the Singapore SG10K project samples, 98.3 million SNPs and small variants were identified, of which more than 50% were previously unreported86. Furthermore, H3Africa studies identified 62 new loci exhibiting strong selection pressure, which were associated with viral immunity, DNA-repair mechanisms and metabolic processes88. Research involving individuals in BioBank Japan identified distinct signals of recent natural selection in loci related to alcohol or nutrition metabolism, absent in African and European populations89. Another study that included data from this biobank along with ancient samples found an association between increased BMI and Jomon ancestry, an ancient hunter-gatherer group in Japan90.

Key clinical applications of diverse genetic data

There are myriad potential clinical applications of diverse genetic data. Three key mechanisms through which these data have a meaningful impact are enabling the discovery of region-specific variants that are not uniformly distributed across the world; identifying predictive variants for drug responses; and facilitating better prediction of disease predisposition in diverse groups of individuals and contexts.

Local variants in global contexts

Region-specific variants represent a cornerstone in deciphering the intricate tapestry of human genetic diversity, offering a nuanced understanding of the evolutionary trajectories and historical dynamics that have shaped human groups worldwide91. Such variants—characterized by substantial disparities in allele frequencies among regions or groups—serve as genetic signatures of past migrations, demographic events and selective pressures and can be relevant for biomedical traits such as levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol5,36. Group-specific variants associated with disease susceptibility shed light on the complex genetic underpinnings of common disorders, informing strategies for disease prevention, diagnosis and treatment92,93. The interpretation of region-specific variants is facilitated by the integration of diverse methodologies, including genomic sequencing, population genetic analyses and other sophisticated statistical approaches. Researchers draw upon vast genomic databases, such as the 1000 Genomes Project and Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), to catalog genetic variation across diverse populations and identify loci harboring region-specific alleles94,95.

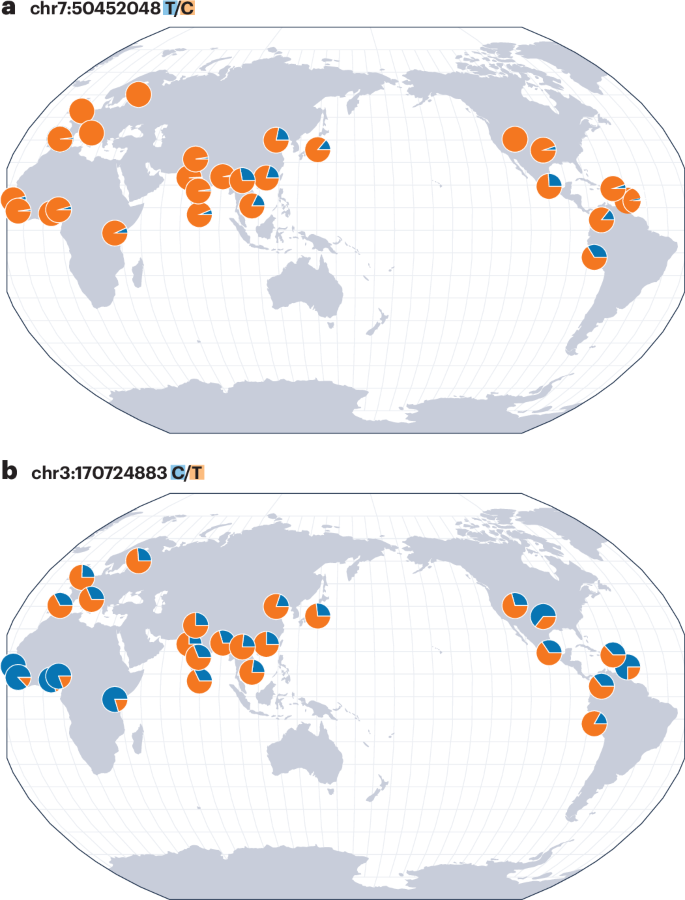

GWASs have shown that the frequency and impact of genetic-susceptibility variants can vary significantly among groups, which could contribute to differences in disease incidence96. For instance, a recent study reported that a non-coding regulatory variant near the transcription factor-encoding gene IKZF1 increases acute lymphoblastic leukemia risk by ∼1.44-fold in Hispanic/Latino children, but not in non-Hispanic white individuals (self-reported ancestry), in a US cohort97. Using global genomic resources, that study found that the risk allele frequency of this variant was ∼18% in Hispanic/Latino cohorts and less than 0.5% in European cohorts97 (Fig. 3a). Similarly, the ABCA1*C230 allele was previously associated with reduced levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and was observed in a region-specific manner in Indigenous groups across North and South America, but not elsewhere36. Another study also demonstrated that population-amplified genetic variants rs1635712 (KIAA0319), rs16869924 (CLNK) and rs2070025 (FGA) confer risk of gout in Polynesian groups14. In the context of T2D, research has shown that although some genetic loci have consistent effects across ethnic groups, others exhibit allelic heterogeneity or population-specific effects, highlighting the importance of conducting genetic studies in diverse cohorts98. Studies on Native Hawaiians also support this point by identifying population-enriched genetic variants associated with cardiometabolic diseases99. Aside from nuclear variants, it is equally important to identify region-specific mitochondrial variations (Box 1); several have now been associated with various metabolic and inflammatory conditions in a population-specific manner100,101,102,103.

Variants that substantially differ in allele frequencies across regions, or that are broadly distributed but have varying effects, are relevant for understanding traits and diseases—and can inform treatment choices. Maps in this figure were generated with the Geography of Genetic Variants Browser, which uses global cohorts from the 1000 Genomes Project147. a, The geographical distribution of allele frequencies of the rs76880433 (T/C) variant near IKZF1, which is associated with increased acute lymphoblastic leukemia risk in Hispanic/Latino children97. The C allele shows a higher frequency in Mexican, Colombian, Peruvian and East Asian cohorts than in the rest of the cohorts. b, The geographical distribution of allele frequencies of the rs8192675 (C/T) variant associated with influencing response to metformin, a commonly used treatment for T2D118,119. A high frequency of the C allele is observed in African and African American cohorts, yet individuals of these ancestries do not demonstrate the same allelic effect as individuals of European ancestries120.

Region-specific genetic findings can enhance drug development, healthcare guidelines and public-health policies by addressing population-specific needs. In drug development, incorporating genetic insights increases the efficacy and safety of medications by tailoring them to distinct genetic profiles, as shown in studies leveraging population genomics for target discovery104. Pharmacogenomic studies (discussed in more detail in the section below) have identified group-specific variants that influence responses to several drug classes, including antineoplastic agents and immunosuppressive, cardiovascular and antimicrobial drugs105. Healthcare guidelines benefit from such analyses, which can enable personalized treatment plans to optimize drug efficacy and minimize adverse reactions106. Public-health policies informed by regional genetic data can identify at-risk populations and mitigate health disparities through targeted screening and prevention strategies107. These approaches collectively advance precision medicine globally108.

However, the study of region-specific variants is not without challenges. Sample-size limitations, inadequate representation of groups in the Global South and confounding factors such as population stratification (whereby genetic structures within a sample correlate with a phenotype) pose substantial hurdles in genetic research109,110,111. Moreover, interpreting the functional significance of region-specific variants and elucidating their causal roles in complex traits requires robust validation and functional characterization112. Collaborative efforts, interdisciplinary approaches and data-sharing initiatives are essential for overcoming these challenges and advancing our understanding of region- or group-specific variants. Machine-learning techniques, such as transfer learning, hold considerable potential for advancing the characterization of rare variant effects113. Longitudinal studies, cohort analyses and integrative multi-omics approaches are essential to unravel the dynamic interplay between genetic variation and environmental factors in shaping the diversity of human traits relevant for biomedicine.

Pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine

Pharmacogenomics is the study of genetic factors that impact drug response114. It examines gene–environment interaction in which medication intake becomes the ‘environment,’ or exposure37. The genetic variation present in drug-target genes and genes encoding molecules involved in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME genes) influences differential drug response115. Pharmacogenes, which regulate the drug response, show greater differences in allele frequency among human groups than do genes associated with diseases, owing to lower evolutionary constraints116,117. So far, pharmacogenomic studies, like other genomic studies, have focused mainly on European genetic ancestries118. Biobanks are important resources for studying drug response; however, it is important that they include relevant phenotypic data, as well as sufficient information about the drug.

A GWAS revealed rs8192675, a single-nucleotide variant located at SLC2A2—which encodes the glucose transporter GLUT2 (refs. 118,119)—as an example of genetic variation influencing drug response (Fig. 3b). This variant influences the response to metformin, a commonly used treatment for T2D: individuals who carry the C allele in homozygous forms have a greater reduction of glycosylated hemoglobin A1C levels in response to the drug119. However, this discovery was made in individuals of European ancestry, and it was not replicated in African-American individuals, in support of the idea that genetic background can be an important factor in drug response and highlighting the importance of diversity in pharmacogenomics120.

Structural variants are not as well-studied as single-nucleotide variants20,115,121. However, it has been shown that structural variation in several known pharmacogenes has a strong influence on drug response118. A recent study described the distributions of structural variants in pharmacogenes (ADME and drug-target genes) among continental groups115. In the case of functional structural variation in drug target genes, this study showed that East Asians harbor the lowest number of variants per individual (0.88), and individuals from Africa show the highest (1.64). Smaller differences were found for functional structural variants in ADME genes: East Asian individuals show the highest value per individual (11.7), whereas individuals from Europe show the lowest (9.4).

A concrete example of the impact of structural variation is seen in CYP2D6. This gene encodes an enzyme that is involved in the metabolism of ~20% of commonly used drugs, such as some antidepressants, antipsychotics and analgesics114,122. Moreover, it is highly polymorphic, showing both single-nucleotide and structural variation, with specific alleles influencing metabolism of certain drugs114,122. The complete deletion of the gene (CYP2D6*5) is heterogeneously distributed among human groups; for instance, at the sub-continental scale within Europe, this deletion shows a decreasing frequency gradient from north to south (6% to 1%)15,114.

Pharmacogenomic research can inform healthcare guidelines for appropriate use of certain treatments105,106. For example, the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium provides guidelines for using CYP2C19 genotype information, with varying allele frequencies in different regions, to guide clopidogrel therapy123. Patients with certain CYP2C19 genetic variants metabolize clopidogrel less effectively, leading to reduced drug efficacy. By identifying these variants through pharmacogenomic testing, healthcare providers can prescribe alternative medications (such as prasugrel or ticagrelor) to improve patient outcomes.

Polygenic prediction and precision medicine

Turning from single variants and genes to genome-wide effects, polygenic scores (PSs) use GWAS data to calculate a numerical score reflecting a person’s predisposition for developing a trait or disease. It is now widely accepted that the predictive accuracy of PSs decreases with greater genetic disparity between the GWAS summary statistics used and the individuals being evaluated. This disparity can occur along axes of the genetic ancestry continuum77, as well as other environmental axes40. Variability in PS accuracy is also observed among individuals in the same ‘group.’ For example, although the precision of polygenic prediction is lower for individuals of Latin American descent than for those of European descent, there are still many individuals from Latin America for whom PS accuracy is comparable to that of individuals of European descent, and this pattern is consistent across various traits77,124.

What factors influence PS precision? Although the effect size of causal effects is heterogeneous among individuals from different continents, individuals of admixed ancestry tend to display consistent effect sizes across the ancestral spectrum in their genomes125; however, heterogeneity persists for traits with substantial polygenic components, such as height. Differences in the precision of polygenic prediction can also be attributed to factors such as the frequency and tagging of causal alleles by SNPs assayed in commonly used GWAS SNP arrays125. For example, PS models aimed at disease prediction (such as PRS-CSx)126 often use the HapMap3 SNP reference panel; however, HapMap3 is suboptimal for tagging genetic variants in non-Europeans127,128, and it excludes structural variants56. Also, non-genetic variables such as sex, age and social determinants of health—including deprivation index—significantly impact the individual PS accuracy40,129, as do differences in data-collection methodologies and inconsistencies in trait or disease definitions among different biobanks125.

Recently developed PS models, such as PRS-CSx126, have improved prediction accuracy in diverse groups by combining GWAS data from multiple ancestries and including group-specific patterns of linkage disequilibrium (the non-random linkage of variants due to proximity and coinheritance, or evolutionary forces). This method assumes largely similar genetic architecture between cohorts while allowing room for specific evolutionary responses and cohort-specific variants. Although these advancements have enhanced accuracy in predicting certain traits, the importance of collecting genetic information from individuals from under-represented groups cannot be overlooked. In the case of Mexican individuals, PSs based on GWAS data from the Mexican Biobank performed as well as or better than those based on the pan-ancestry GWAS from the UK Biobank—despite the UK Biobank GWAS’s inclusion of four times as many individuals5.

In another illustrative example, a recent study explored the shared and distinct mechanisms that might contribute to the development of T2D using a dataset combining diverse cohorts of individuals130. The study identified 12 genetic clusters that are likely associated with biological pathways involved in T2D pathogenesis (such as lipodystrophy 1 and 2 and cholesterol). Partial PSs (estimated in a fraction of the genome) revealed that, although common pathways contribute to T2D risk across continental groups, the proportion of genetic risk attributed to each cluster varies across groups and influences phenotypic differences. For instance, risk variation in lipodystrophy-related clusters can help explain differences in susceptibility to T2D at the same BMI values between individuals of East Asian and European ancestries. This variation also influences T2D risk among individuals in the same continental group: European individuals in the top 10% of the partial PS for the lipodystrophy 1 cluster (linked to fat distribution) had a higher T2D risk than did those in the bottom 10% at the same BMI130. A subsequent study on British Pakistani and British Bangladeshi individuals investigated the tendency of individuals with South Asian ancestries to develop T2D at earlier ages and lower BMI than other ancestry groups. They found that these individuals had a higher predisposition to insulin deficiency and unfavorable fat distribution than did those of European ancestry16. Genetic risk differences were also found between Pakistani and Bangladeshi individuals, underscoring the importance of investigating genetic variation at finer scales rather than relying solely on broad continental classifications.

Although the human pangenome will help us better assemble genome sequences, more genomic and multi-omic representation will enable a deeper understanding of the unique genetic structure of diverse groups of people, as well as the intricate relationships between genes, environmental factors, and traits or diseases. Ultimately, increasing representation in genomic and multi-omic resources will enhance our capacity to predict disease susceptibility and drug response with greater accuracy.

Ethical considerations

Conducting research that involves diverse and often underserved groups, or individuals from ancient populations, raises many ethical issues. Researchers should take the time and effort to understand these issues to inform inclusive and ethical study design, sampling, analysis and dissemination (Box 2). First, it is essential to obtain proper consent. In this context, frameworks such as the CARE (collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility and ethics) principles offer guidance, emphasizing the importance of actions that guarantee Indigenous data governance and ensure a beneficial outcome for the community131. However, it is important to recognize that the implementation of such frameworks is heavily context specific, owing to the unique histories, cultures and make-up of different regions and countries.

Additionally, ancient-DNA experts acknowledge the impact that research on ancient samples can have on underserved groups and have issued recommendations to promote more ethical research practices in the Global South132. These recommendations include active participation in the development of heritage-management regulations, along with community engagement that includes meaningful consultation with the communities, which is crucial for any genetic research involving them, and the incorporation of their perspectives in the research process. There should also be substantial efforts (for example, through focus groups) to understand the best ways to communicate genetic findings to participants and the public, which, again, could be context specific.

Conclusion

The genomes of any two people vary by only about 0.4%, including single-nucleotide and structural variants19. Although small in genetic terms, this diversity has huge implications—not only for understanding our history but for forging paths to better health in the future. Important efforts have been made to increase inclusivity in genomics, such as establishing biobanks in the Global South, developing the human pangenome and creating methods to improve risk prediction in diverse individuals through innovative polygenic scores. To propel this momentum and achieve precision medicine for all (Box 2), the research community must insist on diversifying datasets and methods—considering factors across the ancestral and environmental continuum—to better understand complex traits and diseases across the swath of human diversity.

Responses