Nivolumab plus chemotherapy or ipilimumab in gastroesophageal cancer: exploratory biomarker analyses of a randomized phase 3 trial

Main

Integration of immune checkpoint blockade into the therapeutic armamentarium of advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma has improved outcomes in a disease where standard first-line chemotherapy has median OS of less than 1 year1,2,3,4. Nivolumab, a programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitor, plus chemotherapy, demonstrated superior OS compared with chemotherapy alone in previously untreated, nonhuman epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive advanced gastric, gastroesophageal junction and esophageal adenocarcinoma in the CheckMate 649 study5. Based on these data, nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy is approved for the first-line treatment of this disease in many countries6. In contrast, treatment with nivolumab plus the cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor ipilimumab failed to meet the prespecified hierarchically tested secondary end point of OS versus chemotherapy in patients with programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) combined positive score (CPS) ≥ 5, although responses were more durable and the OS rate was higher at 24 months7.

Nivolumab and ipilimumab elicit antitumor responses by distinct but complementary mechanisms of action8,9. PD-1 inhibition restores the antitumor function of T cells10, whereas CTLA-4 inhibition induces de novo antitumor T cell responses as well as modulation of regulatory T cells11,12,13,14. Anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 combination therapies enhance expansion of tumor-specific T cells, including CD8+ T cells and T helper cells, compared with monotherapies8,15. The observed efficacy of nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy in CheckMate 649 may be attributed to the potentiation of chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity and immunogenic cell death with the antitumor effects of nivolumab16. Therefore, responses to nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy and to nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab are likely driven by distinct molecular or immunophenotypes of the tumor. Identification of pretreatment biomarkers associated with outcomes with nivolumab-based regimens in gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma may help identify patient subgroups that are likely to derive the most clinical benefit.

Among the four molecularly distinct subsets of gastroesophageal cancer17, microsatellite instability (MSI)-high tumors have the most favorable outcomes with immune checkpoint blockade, whereas studies describing tumors with chromosomal instability (CIN) or that are genomically stable (GS) or Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-positive are limited18,19,20,21. Select gene expression signatures (GES) related to inflammation, stroma or angiogenesis were associated with immune checkpoint blockade outcomes across tumor types22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31; however, there has not been a comprehensive DNA or RNA analysis exploring the relationship of various pretreatment tumor characteristics with therapeutic outcomes in metastatic gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. We describe in-depth biomarker analyses from baseline tumors from the CheckMate 649 study to examine the association of biomarkers with survival outcomes in patients treated with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy or nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy.

Results

Patient population

Of 1,581 patients randomized to receive nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy, 685 (43%) were evaluable by whole-exome sequencing (WES) and 809 (51%) were evaluable by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (Supplementary Table 1). Of 813 patients randomized to receive nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy, 366 (45%) were evaluable by WES and 402 (49%) were evaluable by RNA-seq (Supplementary Table 2). At data cutoff (31 May 2022), minimum follow-up (time from concurrent randomization of the last patient to data cutoff) for the nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy group was 36.2 months. Minimum follow-up for the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy group was 47.9 months.

Baseline characteristics were generally balanced between the treatment groups and were consistent for all-randomized, WES-evaluable and RNA-seq-evaluable patients (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Median OS and hazard ratios (HRs) were generally comparable between all-randomized, WES-evaluable and RNA-seq-evaluable patients in both the nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy and nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy groups, suggesting that the biomarker-evaluable populations were representative of the entire randomized population (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

OS by genomic subtypes

Among the WES-evaluable population (n = 889), 41 patients (5%) were EBV positive. Of tumors that did not have sequences mapping to the EBV genome, a Gaussian mixture model of tumor mutational burden (TMB) and CIN scores identified three clusters: 533 (60%) had a high chromosomal instability score and were classified as CIN, 273 (31%) had low chromosomal instability score and were classified as GS and 42 (5%) had high TMB and were classified as hypermutated (Fig. 1a). These subtypes were in alignment with those described by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)17. Further characterization revealed that 37 of 42 (88%) hypermutated tumors were MSI-high (Fig. 1a). Analysis of the genomic subtypes by tumor location revealed that the CIN subtype was predominant in esophageal (86%) and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinomas (72%) (Fig. 1b). Association with histology was consistent with TCGA17, and the diffuse histological subtype was predominant in the GS group (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Although the prevalence of PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 was high in the EBV subtype, no pronounced associations were seen with PD-L1 CPS and genomic subtypes (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

a, Flowchart depicting method of genomic classification of tumors (left). Scatter-plot of TMB versus genomic instability in EBV-negative tumors (right). b, Tumor subtyping by anatomical location. c,d, Forest plot of OS by genomic subsets in patients treated with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy (c) or nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab (d) versus chemotherapy. Data are presented as unstratified HRs and 95% CI. HR was not calculated if the number of patients in each arm was <5. Open circles represent MSI-H, filled circles represent MSS, and squares represent not available (NA). IPI, ipilimumab; MSI-H, MSI-high; NIVO, nivolumab.

The hypermutated subtype benefited most from both nivolumab-based regiments versus chemotherapy (nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy, HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.15–0.90; Fig. 1c; nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab, HR 0.27, 95% CI 0.07–1.06; Fig. 1d).

Patients with CIN subtype derived less benefit from the addition of nivolumab to chemotherapy (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.74–1.13) compared with those with GS (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.52–0.94) or EBV (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.26–1.45) subtypes (Fig. 1c); similar OS trends across these subtypes were also observed in the PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 population (Extended Data Fig. 1c); however, a different trend was observed with nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy, which resulted in an HR of 0.81 (95% CI 0.61–1.08) in the CIN subtype and 0.76 (95% CI 0.22–2.64) in the EBV subtype compared with 1.01 (95% CI 0.70–1.46) in the GS subtype.

OS by TMB and MSI status

Among WES-evaluable patients treated with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy, 57 patients (8%) were TMB-high (TMB-high denotes ≥199 mutations/exome; Fig. 2a). An analysis of the association between TMB and microsatellite instability in patients where both biomarkers were evaluable revealed that all patients with MSI-high tumors also had TMB-high status.

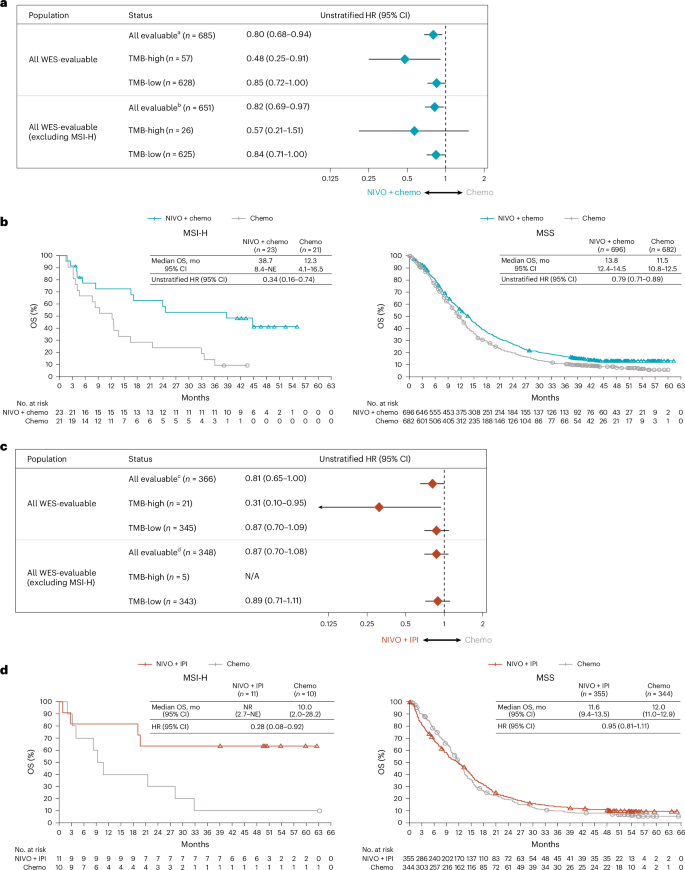

a, Forest plot showing OS by baseline TMB status in patients who received nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy. Data are presented as unstratified HRs and 95% CI. b, Kaplan–Meier curves of OS by microsatellite stability status in patients treated with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy. c, Forest plot showing OS by baseline TMB status in patients who received nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy. d, Kaplan–Meier curves of OS by microsatellite stability status in patients treated with nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy. TMB-high denotes ≥199 mutations per exome, whereas TMB-low denotes <199 mutations per exome. Data are presented as unstratified HRs and 95% CI. HR was not calculated if the number of patients in each arm was <5. aTMB not evaluable (NE)/available in 896 patients (NIVO + chemo: n = 431; Chemo: n = 465). bTMB not evaluable/available in 727 patients (NIVO + chemo: n = 355; Chemo: n = 372). cTMB not evaluable/available in 447 patients (NIVO + IPI: n = 226; Chemo: n = 221). dTMB not evaluable/available in 351 patients (NIVO + IPI: n = 181; Chemo: n = 170).

The magnitude of OS benefit seemed higher with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy in patients with TMB-high tumors (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.25–0.91) compared with those with TMB-low tumors (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72–1.00). A similar trend was observed when MSI-high patients were excluded from the analysis, suggesting that the association was not solely driven by MSI-high patients (Fig. 2a). The enrichment of OS benefit in TMB-high tumors with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy was consistently observed in patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 tumors (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.21–0.89; Extended Data Fig. 2a). The number of patients with TMB-high and PD-L1 CPS < 5 was less than 5 per treatment group; therefore, OS benefit could not be evaluated. In patients with MSI-high tumors, the magnitude of OS benefit was enriched compared with the overall population treated with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy (HR 0.34, 95% CI 0.16–0.74; Fig. 2b), although sample sizes were small; patients with microsatellite stable (MSS) tumors had OS benefit similar to that of the overall population (MSS, HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.71–0.89; Fig. 2b; overall population, HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.60–0.79)5.

Patients with TMB-high tumors seemed to benefit from nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab (HR 0.31, 95% CI 0.10–0.95), although the sample size in the TMB-high group was small (Fig. 2c); similar results were also observed in patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 (Extended Data Fig. 2b). In patients with MSI-high tumors, OS benefit was observed with nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy (HR 0.28, 95% CI 0.08–0.92) (Fig. 2d). OS results in patients with MSS tumors (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.81–1.11) were consistent with the overall patient population7 (Fig. 2d).

OS by genetic alterations

To characterize the impact of alterations in gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma-relevant genes, association of genetic changes (mutations or copy number) with OS was evaluated (Extended Data Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 3). The most frequently altered genes among patients were TP53 (55%), ARID1A (13%) and KRAS (12%). The results suggest a general trend toward OS benefit with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy across gene alteration subgroups; however, the interpretation is limited due to the small number of patients within each genomic subset, which led to wide confidence intervals (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Although benefit was observed regardless of KRAS alteration status, a higher magnitude of benefit was noted within the KRAS-altered subgroup (HR 0.53; Fig. 3a). Similar trends were observed when KRAS alterations were further categorized as mutations or amplifications; 31 patients (5%) had KRAS mutations, and 52 patients (8%) had KRAS amplifications (Fig. 3b). Most KRAS mutations seemed to occur at the G12 and G13 codons (Fig. 3c). Gene alterations did not have a notable impact on OS with nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy (Extended Data Fig. 3c), although patient numbers were small within some subgroups.

a, Kaplan–Meier estimates of OS in all WES-evaluable patients with altered (left) or unaltered (right) KRAS mutations + amplifications. b, OS by baseline KRAS pathway alteration status derived from the model, including interaction of KRAS alteration status with treatment, MSI and TMB status. Data are presented as unstratified HRs and 95% CI. c, KRAS mutation map. aMSI status not evaluable/available in two patients. KRAS, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene.

OS by GES

Baseline tumor GES of potential clinically and biologically relevant pathways spanning intrinsic and extrinsic tumor microenvironment factors (Supplementary Table 4) were evaluated for correlation with each other and separated into three modules: MAPK/hypoxia/glycolysis/proliferation, inflammation and angiogenesis/stroma. Inflammation-related GES including regulatory T (Treg) cells showed moderate-to-strong correlation with each other (Fig. 4a). In the MAPK/hypoxia/glycolysis/proliferation module, the 34-gene MAPK GES was highly correlated with proliferation (Spearman’s correlation ρ = 0.9), hypoxia (Spearman’s correlation ρ ≥ 0.5) and glycolysis-related GES (Spearman’s correlation ρ = 0.7) (Fig. 4a). These observations were recapitulated when patients were clustered based on the same signatures, and grouped into three clusters, similar to the three modules in Fig. 4a. Tumors tended to have similar expression patterns of different signatures within the same cluster. CIN tumors tended to be enriched in patients with higher expression of MAPK/hypoxia/glycolysis/proliferation-related GES, and PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 tumors were more frequently observed in patients with higher inflammation-related GES (Fig. 4b).

a, Correlation of gene signatures among all RNA-seq evaluable patients. Numbers indicate the Spearman’s correlation. The strength of association is indicated by the color scale shown on the right. b, Heatmap of baseline tumors clustered by the gene signatures of interest in patients treated with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy, nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab or chemotherapy. For visualization purposes, each gene signature was first normalized by z-score method where samples with high z-score (red) indicates relative high gene signature score and low z-score (blue) indicates relative low gene signature score. Patients (column) were ordered based on similarity of gene signatures of their tumor samples via hierarchical clustering method. Dendrogram (top) was added to show the hierarchical relationship between samples. Similarly, gene signatures (rows) were ordered and dendrogram (left) was added to show the hierarchical relationship between gene signatures. aMutations per exome.

Several GES were associated with OS benefit from nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy (P < 0.1; likelihood ratio test (LRT)) (Extended Data Fig. 4a). This included multiple angiogenesis-, MAPK- and stroma-related signatures (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Further stratification of all RNA-seq-evaluable patients into tertiles based on GES high, medium or low scores was performed, and the results were visualized using Kaplan–Meier curves and forest plots (Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 5). Low angiogenesis GES scores were associated with improved OS benefit in all-evaluable patients and those with PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 or CPS < 5 (five-gene angiogenesis (low), all-evaluable, HR 0.68; CPS ≥ 5, HR 0.62; CPS < 5, HR 0.66; Fig. 5a,b and Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). Low stroma and high MAPK GES scores were also associated with improved OS with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy in the all-evaluable and PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 subgroups (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 5b). No obvious associations of OS benefit with inflammatory GES were observed.

a, Forest plot showing the correlation between OS and selected signatures used to stratify patients into tertiles (high, medium or low). Data are presented as unstratified HRs and 95% CI. HR was not calculated if the number of patients in each arm was <5. b, Kaplan–Meier estimates of OS in all RNA-seq-evaluable patients with low, medium or high angiogenesis GES scores (five-gene angiogenesis) at baseline.

Associations were also observed between GES and OS benefit in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy group (P < 0.1; LRT); these GES included angiogenesis-, glycolysis-, hypoxia-, inflammatory-, chemokine-, Treg cell-, MAPK-, proliferation- and stroma-related signatures (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Numerous GES subgroups by tertiles showed OS benefit with nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy (Fig. 6). OS benefit was observed in patients with high inflammation GES scores among all-evaluable patients (12-gene chemokine (high), HR, 0.59; ten-gene inflammation (high), HR 0.63; Fig. 5) and those with PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 (HR 0.77; Extended Data Fig. 6). Improved OS was also observed in patients with high Treg GES score regardless of PD-L1 status (two-gene Treg cell (high), all-evaluable, HR 0.59; PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5, HR 0.57; PD-L1 CPS < 5, HR 0.51); the Kaplan–Meier OS curves for these subgroups demonstrated no evidence of an early detriment with nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy (Fig. 5a,b and Extended Data Fig. 7). Multivariate analysis adjusting for baseline inflammation demonstrated a similar association of high Treg cell GES scores with OS benefit for nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy, suggesting that this effect was not driven by baseline inflammation levels (Treg cell (high) adjusted by ten-gene inflammation, all-evaluable, HR 0.57 (95% CI 0.39–0.83); PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5, HR 0.57 (95% CI 0.35–0.92); PD-L1 CPS < 5, HR 0.46 (95% CI 0.24–0.86)). A summary of the various GES potentially associated with efficacy with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy or nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab is provided in Extended Data Fig. 8.

a, Forest plot showing the correlation between OS and selected signatures used to stratify patients into tertiles (high, medium or low). Data are presented as unstratified HRs and 95% CI. HR was not calculated if the number of patients in each arm was <5. b, Kaplan–Meier estimates of OS in all RNA-seq-evaluable patients with high, medium or low Treg cell GES scores (two-gene Treg cell) at baseline.

To further explore associations of GES with efficacy of nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy or nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted (Extended Data Fig. 9). Enrichment of inflammation-related gene sets (interferon_alpha_response and allograft_rejection)32,33 were prognostic for OS benefit in both nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy and chemotherapy (false discovery rate <0.01); however, these were predictive of better OS benefit with nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy (Extended Data Fig. 9). Cell cycle-related gene sets (MYC_targets_v1, G2M_checkpoint and E2F_targets) were enriched with genes predictive of better OS with both nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy or nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy (Extended Data Fig. 9). The epithelial–mesenchymal transition gene set was prognostic of worse OS in all three treatment groups (adjusted P value of interaction >0.9; Extended Data Fig. 9).

Discussion

This analysis from the CheckMate 649 study utilized large-scale WES and RNA-seq analyses to gain deeper understanding of signaling pathways associated with favorable outcomes with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy or nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy. To our knowledge, this study provides the largest WES and RNA-seq datasets with first-line immune checkpoint blockade in gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma.

Genomic subtyping analyses of all WES-evaluable tumors from CheckMate 649 showed that the CIN subtype was predominant in esophageal and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinomas. In WES-evaluable patients, differential associations of OS benefit with genomic subtypes were observed for nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy and nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy. Greater OS benefit was observed with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy and with nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy among patients with the hypermutated subtype, followed by EBV; however, the small sample size in this subgroup limits interpretation.

Several studies have shown that CIN is linked to cancer progression and metastasis due to increased cancer cell migration and immune evasion34,35,36. One of the CIN-driven mechanisms to evade the immune system is the chronic activation of the cGAS–STING pathway, which increases resistance to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment35,36,37. In CheckMate 649, adding ipilimumab to nivolumab may have potentially reduced the effect of this immune evasion in CIN tumors, leading to OS benefit, although further confirmation is required. Novel therapeutic options and combination strategies may be needed to further improve outcomes in patients with CIN tumors.

OS benefit with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy was generally observed regardless of gene alteration status; alterations in TP53, ARID1A and KRAS were the most common in these analyses. Notably, patients with tumors harboring KRAS alterations derived a higher magnitude of benefit with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy compared with the KRAS-unaltered subgroup. Although definitive conclusions cannot be drawn from these findings due to small patient numbers in some subgroups, similar results were reported in lung cancer studies, where there were better outcomes with immunotherapy-based regimens than with chemotherapy-based regimens38,39,40. The underlying mechanisms for the improved efficacy with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy in gastric tumors with KRAS alterations are yet to be established. However, several studies previously demonstrated that mutant KRAS promotes an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment through multiple mechanisms, such as increased release of IL-10 and TGF-β via the ERK–MAPK pathway, resulting in promotion of Treg cells and inhibition of CD8+ T cell activity41,42. Blocking PD-1 can counteract these effects by reinvigorating CD8+ T cell responses and reducing the immunosuppressive impact of mutant KRAS on the tumor microenvironment, leading to potentially better outcomes in KRAS-mutant cancers under immune checkpoint inhibition. In addition, oncogenic KRAS signaling is capable of upregulating noncoding transcripts arising from transposable elements, which are known to increase tumor immunogenicity43. These factors may lead to an increased susceptibility to immunotherapies.

TMB is lower in gastroesophageal cancers compared with lung cancer and melanoma44. Consistent with these data, 8% of patients evaluable for this biomarker had TMB-high tumors in this study; all TMB-high tumors were also MSI-high. Nevertheless, a trend toward improved OS benefit with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy or nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy was observed among patients with high TMB, in both all-randomized and PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 populations. Similar results have been reported in other tumor types following treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors22,23,24,25,26,45; however, this relationship could not be evaluated in patients with high TMB and PD-L1 CPS < 5 due to small sample size.

In RNA-seq analyses, subgroups with low angiogenesis and low stroma GES scores were associated with greater OS benefit with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy and nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy. Notably, low angiogenesis GES scores were associated with OS benefit of nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy even in the PD-L1 CPS < 5 subgroup. These findings are aligned with the known interplay of angiogenesis and stromal/fibroblast signaling that leads to immune suppression and resistance to immune checkpoint blockade, likely through impaired vasculature and stromal aberrations resulting in reduced perfusion limiting the entry and function of effector T cells into the tumor microenvironment46,47,48,49. Furthermore, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which plays a critical role in angiogenesis, activates and recruits immune suppressive cells such as Treg cells and tumor-associated macrophages50. The combination of immunotherapy and anti-angiogenic/anti-fibroblast agents may potentially overcome tumor resistance to anticancer agents and improve treatment outcomes in gastroesophageal cancer51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. Tumor T cell inflammation is a known predictive biomarker for immune checkpoint blockade in gastroesophageal and other tumor types29,60,61. Notably, although our analyses indicated an association between baseline inflammation and efficacy of nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab, the trend was less obvious with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy. This may be due to activation of proinflammatory signaling following chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity and immunogenic cell death resulting in reduced dependence of nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy antitumor activity on baseline inflammation16,62.

High numbers of tumor-infiltrating Treg cells are correlated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer and other tumor types63,64,65,66 and with possible resistance to PD-1 inhibitor therapy67,68. In the current analysis, high Treg cell GES scores emerged as unique signatures associated with OS benefit from nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy regardless of PD-L1 CPS status. The association of high Treg cell GES scores with OS benefit was still observed when adjusted for baseline inflammation, despite the known correlation between Treg cell GES and inflammation. This may be attributed to ipilimumab-driven Treg cell modulation, enhanced ratio of effector T to Treg cells and CD4+ T cell activation69. Further studies are needed to confirm the mechanistic interaction of ipilimumab with effector T and Treg cells in gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Proliferation GES are known to be associated with better response to immunotherapy70,71, and high proliferation was associated with OS benefit with nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy in our analysis. Glycolysis and hypoxia GES, which showed moderate-to-strong correlation with proliferation GES, were also associated with potential benefit of nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy. The results from GSEA were largely consistent with RNA-seq data, supporting the robustness of this analysis. Of note, cell cycle-related gene sets, which correlate with cell cycle progression and MAPK pathway activation, were predictive of better OS with both nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy and nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy, consistent with the GES analysis that demonstrated the association between MAPK GES and OS benefit for both nivolumab-based regimens. Interestingly, KRAS alteration was associated with higher OS benefit in patients treated with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy but not nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy, indicating that MAPK pathway influence on cancer outcome is not dictated by KRAS alteration status. The minor differences observed between RNA-seq and GSEA may be due to some variations in the genes between the hallmark gene sets used in the GSEA and those that comprised the GES.

The current analyses have some limitations. Although the biomarker-evaluable populations were generally representative of the all-randomized study population with respect to demographics, baseline clinical characteristics and outcomes, the small sample sizes of each biomarker subgroup may have resulted in imbalances that are not captured by these measurements. Additionally, these retrospective biomarker analyses were exploratory and therefore were not formally tested or intended to determine statistical significance. Thus, the utility of these biomarkers requires further prospective clinical validation.

This exploratory biomarker analysis from the CheckMate 649 study identified patient populations with gastric, gastroesophageal junction and esophageal adenocarcinoma that seem to derive greater OS benefit from first-line nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy or potential benefit from nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy. The pattern of biomarkers identified in this analysis suggests a role for overlapping (anti-PD-1) and distinct (anti-CTLA-4) mechanisms from these immunotherapy regimens. Additional prospective clinical studies are needed to determine if these predictive biomarkers hold clinical utility for treatment selection.

Methods

Inclusion and ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the trial protocol and with Good Clinical Practice guidelines developed by the International Council for Harmonisation. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients per the Declaration of Helsinki principles. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02872116).

Study design and patients

Key eligibility criteria and other study details of the CheckMate 649 study have been previously published5,7. Briefly, adult patients with previously untreated, unresectable or advanced gastric, gastroesophageal and esophageal adenocarcinoma were randomized to receive nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy, nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab or chemotherapy alone. Patients in the CheckMate 649 study who provided appropriate consent for the biomarker testing with evaluable baseline tumor tissue and matched whole-blood samples that passed the quality control (QC) criteria were eligible for the WES analyses, and those with evaluable baseline tumor samples that passed the QC criteria were eligible for the RNA-seq analyses. OS was assessed in patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 treated with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy (primary end point), in all-randomized patients treated with nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy (secondary end point) and in patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 and all-randomized patients treated with nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy (secondary end point). Further details can be found in the supplementary information.

Definitions for gene alterations

Genes analyzed were selected based on previous mutational analyses in gastric or esophageal carcinoma17,72. For each gene of interest, an anticipated functional impact of alteration (gain of function or loss of function) was assigned based on previous evidence in gastric or esophageal carcinoma and/or other indications. Somatic mutations and copy number changes were mapped to each gene based on anticipated functional impact.

For mutations in genes with anticipated loss of function, individual somatic mutations were classified as loss of function if predicted to alter the amino acid sequence of a gene (specifically, frameshift mutations, mutations resulting in premature truncation and splice acceptor or donor variants) or if occurring at a known cancer hotspot72; deletions were classified as a loss of function alteration.

For mutations in genes with anticipated gain of function and recurrently mutated in cancer (and present in the list of hotspot mutations73), individual somatic mutations were classified as gain of function if occurring at a known recurrent hotspot. For mutations in genes with anticipated gain of function that were not recurrently mutated in cancer (not present in the list of hotspot mutations), any missense mutation was considered a gain of function; amplifications were classified as a gain-of-function alteration.

Oncoprint-style visualizations were generated using R package ComplexHeatmap (v.2.12.1); lollipop-style visualizations representing the location of mutations in KRAS were generated using the R package maftools (v.2.12).

Whole-exome sequencing

Baseline tumor tissue and matched whole-blood samples were processed using the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V6 in-solution hybrid capture panel and underwent subsequent next-generation sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq platform. Sequence alignment and variant calling were performed. Specifically, BAM files were generated from the paired FASTQ files following the Broad Institute’s best practices, using Sentieon implementation of the GATK pipeline74,75. The paired reads were aligned to the reference genome using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner’s Maximal Exact Match (BWA-MEM) algorithm76,77,78 and sorted; duplicate reads were marked using Sentieon Dedup algorithm. During this process, Sentieon and Picard metrics were generated. A WES QC report was generated, which marked tumor samples PASS if total reads 45 million, mean target coverage 50× and depth of coverage >20× at 80% of the targeted capture region or higher. Normal samples were marked PASS if total reads 25 million, mean target coverage 25× and depth of coverage >20× at 80% of the targeted capture region or higher79. Somatic single-nucleotide variants and indels were then called by two variant callers: Tnscope (Sentieon Inc., based on and mathematically identical to the Broad Institute’s MuTect2 (ref. 80) and Strelka2 (ref. 81)). A consensus set of PASS variants called by both Tnscope and Strelka2 for the targets and bait bed files of a WES capture kit was produced to capture high-confidence variants. Annotations were then added using SnpEff82 from dbSNP83, ExAC84 and genomAD85. Variants either not present in or present at <0.01% allele frequency in the ExAC database84 were retained for further analysis.

PD-L1 expression

PD-L1 expression was assessed at baseline in fresh biopsy specimens or from archival tumor tissue as described previously5,7. PD-L1 CPS was determined using a validated immunohistochemistry assay (Dako PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx assay; Agilent Technologies Inc.) as described previously29.

TMB assessment

TMB was evaluated in patients who had sufficient WES to pass QC. Any variants that were found in gnomAD were excluded from the TMB calculation. Tissue TMB was defined as the total number of somatic missense mutations at the target region of capture kit used for the WES assay and identified by both Strelka2 and Tnscope somatic variant callers after filtering for the PASS variant only86. High TMB was defined as ≥199 mutations per exome and low TMB as <199 mutations per exome. The threshold of 199 mutations/exome is equivalent to ten mutations per megabase per Foundation Medicine F1CDx panel87.

Detection of EBV in WES

PathSeq, a component of the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK)88, was used to identify EBV reads from WES data. Specifically, reference genomes from both the host (human, hg38) and microbe (RefSeq bacteria and viral genomic sequences downloaded from ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/refseq/) were first prepared including index images construction, host k-mer library file generation and assembly of a taxonomy file derived from the microbe sequences, NCBI taxonomy dump (taxdump.tar.gz) and RefSeq accession catalog (RefSeq-release218.catalog.gz). PathSeq was then executed using the parameter ‘—is-host-aligned false’ with a 90% sequence identity threshold set for the classification of microbial reads. Subsequently, the counts of reads mapped to EBV (taxonomy ID 10376) were extracted.

Genomic subtype classification

WES-evaluable tumor samples were categorized into four subtypes: EBV positive, hypermutated, GS and CIN. EBV-positive tumors were defined as those tumors with at least one read mapped to the EBV genome. For tumors without reads mapped to the EBV genome, a Gaussian mixture model was fitted to two metrics derived from WES data: TMB (log10 scale) and CIN score (log10 scale) using mclust (v.5.4.7) with no prior and default control parameters for expectation–maximization89. To quantify the degree of aneuploidy, GISTIC2.0 (ref. 90) was applied to the copy-number variation (CNV) data from the preprocessed WES data using GATK v.4.0. The CIN score was defined as the summation of square of gene-level GISTIC2.0 values as described previously91. The Bayesian information criterion was used to select the number of clusters (n = 3) that corresponds to hypermutated, GS and CIN subtypes and covariance parameterization. Tumors were assigned to clusters based on maximum probability of cluster membership.

Assessment of genomic alterations

MSI testing was conducted by Idylla MSI test of baseline tumor tissues. BROAD Best Practices Somatic CNV Panel Workflow (GATK v.4.1.0.0) and Control-FREEC LOH (v.11.6)92 were run in parallel for CNV detection. High-confidence CNV calls from both tools were retained for further analysis. Amplifications were defined as a copy number of >3 and deletions were defined as a copy number <1.5 by both tools.

Gene expression profiling

Gene expression profiling was performed retrospectively using RNA-seq on a subset of baseline tumor samples. Pretreatment tumor tissues were processed using the Illumina TruSeq RNA Access in-solution hybrid capture panel and underwent subsequent next-generation sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq platform. Paired-end FASTQ files were processed on Seven Bridges platform (Seven Bridges Genomics). Specifically, RNA-seq data were filtered by pre-aligning with STAR93 to a microbial contaminant database downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank. Samples with ≤5% of total reads mapping to the contamination database were aligned to the human genome (GRCh38) using the Ensembl 91 gene model and quantified using RSEM to optimally assign multimapping reads. Samples with <85% alignment rate were excluded from analysis. Sequencing quality was assessed using the Picard QC toolkit and DupRadar94 to additionally quantify PCR artifacts using the following criteria: (1) Picard MarkDuplicates Estimated Library Size ≥3,000,000; (2) DupRadar Deduplicated Dynamic Range >265; (3) reads mapping to hemoglobin ≤5%; and (4) reads mapping to ribosomal regions ≤5%. Samples that failed to meet any of these criteria were excluded from the analysis.

Quantified raw counts from the remaining samples were normalized using edgeR trimmed mean of M (TMM) method95 and normalized counts per million were log2 transformed for further analysis. TMM-normalized counts per million were z-scored (normalized to a mean of 0 and s.d. of 1) across all patients in the GES-evaluable group. For each patient, the GES score is defined as the median over the selected genes of the z-scored normalized expression values. The GES were categorized into tertiles (GES high, medium or low) by signature scores. The GES analyzed in all RNA-seq-evaluable patients are listed in Supplementary Table 4. For GES evaluations, moderate-to-strong correlations were defined as a Spearman’s correlation of ρ ≥ 0.4. The interaction between treatment and each GES score was assessed using LRT by comparing two models (model 1, OS ~ Arm + GES; model 2, OS ~ Arm + GES + Arm:GES), where Arm:GES refers to arm-by-GES interaction and GES was treated as a continuous value using a linear Cox proportional hazards (PH) model. Selected signatures (P from LRT <0.1) were used for further investigation by stratifying patients into tertiles based on signature scores.

GSEA methods

GSEA was performed to identify pathways and processes that may be associated with OS in three treatment arms as well as differential treatment effect in nivolumab-plus-chemotherapy or nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab versus chemotherapy. The association of expression of each gene with OS was evaluated using a Cox PH model (OS ~ Arm + Gene + Arm:Gene + Covariates) where Arm:Gene refers to arm-by-gene interaction. Gene refers to the continuous expression (log2 scale) of protein coding, constant regions of Ig (IG_C_gene) and T cell receptors (TR_C_gene). Covariates included prognostic factors such as age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, region, primary tumor location, disease status, Lauren classification, peritoneal metastases, previous surgery related to current cancer or radiotherapy before randomization, number of organs with baseline lesion, signet ring cell and planned chemotherapy regimen as well as PD-L1 CPS level and RNA-seq batch ID. Reverse signed Wald test z-scores from the Cox PH models were ranked and then evaluated with the GSEA algorithm (fgsea v.1.16.0) on the HALLMARK gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database33,96 per arm and arm-by-gene interaction.

Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted using R v.4.0.3. Patient characteristics and clinical outcomes were compared between the biomarker-evaluable population and the intent-to-treat population using frequency statistics and descriptive statistics. Calculated P values were nominal (not adjusted for multiple testing unless otherwise stated), descriptive and not intended to demonstrate statistical significance. Survival analyses were conducted using the R survival (v.3.2-7) and survminer (https://github.com/kassambara/survminer) (v.0.4.8) packages. HR and 95% CIs for OS were assessed by unstratified Cox PH models and visualized using Kaplan–Meier analyses and forest plots. Comparisons among groups used Mann–Whitney U-test (two groups) and Kruskal–Wallis test (three or more groups) for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables.

Association of gene alterations with OS within subgroups of patients were tested using an unstratified Cox PH model. In tumors with higher TMB, higher likelihoods of gene mutations are expected; therefore, analysis of gene alteration status with outcomes control for TMB and MSI. Median OS and 95% CI were computed using a log–log-transformed model.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses