Temporal dynamics and global flows of insect invasions in an era of globalization

Introduction

Ongoing human-mediated movements of insects around the world have led to the establishment of more than 6,700 insect species outside their native ranges, and this number is expected to increase dramatically over the coming years1,2. Non-native species of insects outnumber all other non-native animal species3,4. They have a wide range of ecological effects, such as outcompeting and displacing native species, disrupting food webs, affecting nutrient cycling and changing vegetation structure5,6,7,8. Non-native insects are infamous as forest pests, including species such as the spongy moth (Lymantria dispar), which causes widespread defoliation, and the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis), which has killed tens of millions of ash trees5. More than 1,300 species of non-native insects are considered major threats to agriculture9. A prominent example is the Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata), which is native to sub-Saharan Africa and a major pest of various fruit crops in several world regions including Europe, Asia, Central and South America, causing harvest losses of up to 100% (ref. 5). Furthermore, non-native insects are well known vectors of many human and animal diseases10. The tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), which is spreading rapidly throughout Europe, is a vector of 22 arboviruses, including the dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever viruses10. Economic costs associated with insect invasions are estimated to total US $70 billion annually, with health costs amounting to US $6.9 billion11. Despite their importance as invaders, non-native insects have received disproportionally less attention by invasion biologists compared with non-native organisms in other taxonomic groups, especially plants12.

Humanity’s dominance, propensity to expand, to trade and to domesticate a wide variety of plant and animal species has dramatically influenced the history of human-mediated dispersal for thousands of years13. Despite this long history, most research on invasion dynamics has focused on modern post-1950 globalization of trade and travel and considers globalization to be a steadily rising phenomenon responsible for the steep acceleration of global species introductions14,15,16. However, some species introductions can be traced back to the earliest human migrations and the spread of agriculture, which occurred over 10,000 years ago13. Furthermore, the magnitude of global exchanges has not increased steadily but has fluctuated over time — decreasing during times of economic crises, for example17. Large-scale geopolitical events, such as the rise and fall of European colonialism, have affected the global movements of commodities and people. In addition, technological innovations have also influenced the nature of species spread. For example, the containerization of products greatly increased both the speed and efficiency of product transport, but also enhanced the survival of stowaway species1. The ease of access to the internet in the twenty-first century has enabled online trading, including the trade of exotic pets, which has the potential to become a major pathway for non-native species introduction and spread18,19.

We need to understand how different aspects of global trade affect the spread of non-native insects, and biological theory alone cannot explain where, when and how species invade20. The field of invasion biology has made great progress in better understanding the roles of habitat or species characteristics that affect invasion success21,22,23,24,25 but less attention has been given to human-mediated dispersal26. There is an urgent need to investigate human-mediated spread of species globally27. However, a broad-scale synthesis of temporal dynamics and spatial patterns of insect invasions in the light of ongoing globalization is still lacking.

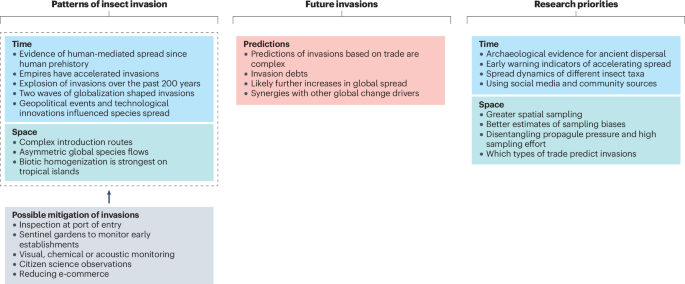

In this Review, we synthesize research on the effects of globalization on temporal dynamics and spatial patterns of insect invasions and highlight research priorities in these areas. We summarize predictions for future invasions and explore possible options for the mitigation of further invasions (Fig. 1). We conclude that non-native insect introduction routes are often complex, resulting in a high frequency of secondary introductions from trade or transport hubs found in interceptions at ports of entry. Global intercontinental flows of insects disproportionately originate from the European Palaearctic, whereas the Afrotropics, Neotropics and Indomalaya have incurred large invasion debts as recipient regions. We find that insect invasions have led to biotic homogenization of communities, particularly on tropical islands, and the erosion of biogeographic boundaries. Moreover, we expect invasions to increase further and their dynamics to shift, especially with the opening of trade routes and introduction pathways.

Synthesis of the key points of this Review, summarizing how globalization of trade and transport affects patterns of global insect invasions over time and space. Mitigation strategies and future research priorities to develop a better understanding of global insect invasions are indicated. Interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial to research in the invasion science field and will influence future research priorities.

Temporal dynamics since prehistory

Insect invasions have a long history, which started when humans began to migrate and intensified with the advent of agriculture and with increased modes of transportation. However, the spread of non-native species greatly accelerated after the Industrial Revolution, when globalized trade and travel became faster and more efficient. This general acceleration of invasions is, however, punctuated by specific geopolitical events.

Neolithic humans facilitated insect dispersal

Insects have been living in close association with humans since human prehistory28 and have been dispersed through human movement possibly since the first human migrations out of Africa, as early as 177 thousand years ago (ka)29,30. The earliest archaeological evidence of human-mediated dispersal of insects can be dated to 10 ka (ref. 28) (Fig. 2). Humans eventually colonized every continent, reaching Oceania between 65 ka and 50 ka (refs. 31,32) and the Americas around 15 ka (ref. 33). Owing to the rarity of insect fossil preservation from that time and the lack of dedicated research34, records of insect dispersal pre-dating agriculture are scarce35. Plant and animal domestication has been dated to the mid-Neolithic period (around 12 ka), leading to the spread of early farming and a substantial increase in human populations driven by increased resource availability36. Several plant and animal species were intentionally introduced to new regions for agricultural purposes as humans continued to expand their range36, in the process accidentally dispersing insects associated with crops37, livestock30 and pets38.

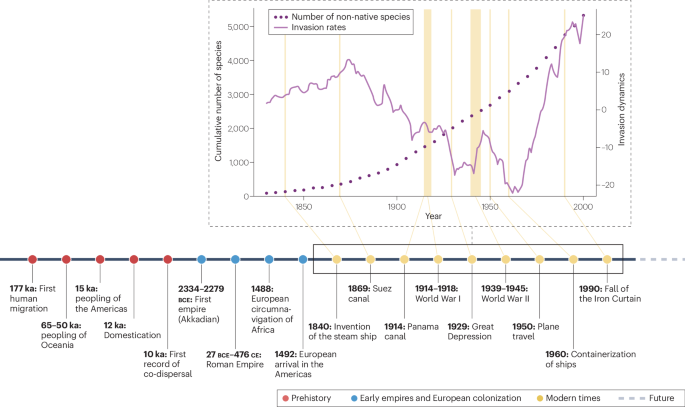

Multiple facets of the history of human globalization (timeline) have influenced invasion dynamics (purple dotted line) and resulted in the accumulation of non-native species over time (purple solid line). The total number of established non-native insect species is based on the FirstRecord database (https://dataportal.senckenberg.de/dataset/global-alien-species-first-record-database) as of July 2024 (ref. 4). Global insect invasion rates account for variations in sampling effort over time based on a null model of insect invasion dynamics52.

Surplus resources as a result of improving agricultural technologies amplified the need for long-term food storage, creating ecological niches that facilitated the movement and establishment of insect pests such as the grain weevil (Sitophilus granarius), which could have caused considerable losses of harvested grain35. Being flightless, and therefore having limited dispersal capacity, the synchronous appearance of grain weevils across scattered archaeological sites can be interpreted as evidence of the early spread of a pest in an emerging agricultural context35. Evidence of insect feeding activity in unexpected locations, such as outside their historical ranges, can sometimes be interpreted as evidence of unintentional trade-linked introduction; for example, the detection of a storage-associated weevil (Rhyzopertba dominica) in Santorini, Greece35.

The advent of early long-distance trade routes

The advent of Bronze Age (about 3000 bce) and Iron Age (1200 bce) ancient empires39 and their trade routes, such as the Silk Roads in Eurasia (around 138 bce to 1453 ce) expanded human movement and long-distance trade. Genetic analyses indicate that this expansion led to global introduction of non-native insects, mostly through intentional dispersal of domesticated hosts40,41. Complementing archaeological evidence with genetic analyses can help to retrace historical insect movements42. Trading of peaches in Eurasia along the Silk Roads seems to have shaped the current distribution of the mealy peach aphid (Hyalopterus arundiniformis)40. Similarly, the small cabbage white butterfly (Pieris rapae) was dispersed along the Silk Roads43. It is likely that many other species yet to be studied were similarly dispersed. Alongside the increased trading facilitated by the Eurasian Silk Roads, the Islamic Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates also intensified commercial and military activities, thereby probably contributing to the accidental dispersal of several insect species44. Population genomic data suggest that the German cockroach (Blattella germanica) originates from Asia, where its closest ancestor lives in close association with human settlements. It has been estimated that this species spread westwards to the Middle East around 1,200 years ago along these early Islamic trade routes44.

Species introduced in such historic periods can now be mistaken for native species, because they have become an integral part of ecosystems and human economies and culture, as is the case for the cochineal (a scale insect)45 and the Chinese oak silkworm (Antheraea pernyi)46. Debate exists as to whether these long-naturalized species should be considered native or non-native47, with implications for restoration and management priorities.

Colonization promoted invasions

Exploration and colonization by European empires between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries marked the beginning of modern globalization. The advent of modern colonialism has been a major driver of the increase in biological invasions that transformed patterns of species movement from sporadic introductions within continents to frequent, repeated and intentional introductions from one continent to another48. Colonists brought crops and livestock with them and transported weeds and insects as stowaways on imperial ships48. The global distribution of non-native plants still bears signatures of European colonialism, in that the compositional similarity of the floras is higher than expected in regions that once were occupied by the same empire49. However, the effect of European colonialism on non-native insect distributions still requires careful investigation. In former European colonies, most non-native insects that have established so far have originated from Europe. For example, in Canada and Chile, 41% and 50% of non-native insects are of Palaearctic origin50,51.

Rising invasions over the past 200 years

The past two hundred years have seen a phenomenal increase in new records of non-native species4, which have occurred in two main waves52: 1850–1914, and 1960 to the present day. These waves correspond to two historical periods of globalization characterized by abundant open trade and separated by a long period with a global recession and two world wars52.

The 1840s marked the beginning of major technological advances leading to an unprecedented expansion of global trade. The invention of the steam ship (around the 1840s) and the use of containers on trading ships (around the 1960s) enabled faster and more efficient transport, while also facilitating introductions of non-native insect species53. In particular, refrigerated containers and wood-based packaging materials both provide excellent conditions for insect survival54. Owing to these new technologies, a single container could cover 75,762 km in one shipping trip (421 days)53. As well as posing ecological problems, these global insect introductions posed a risk to human health by transporting disease vectors55.

The advent of affordable freight and travel starting around the 1950s also contributed to the observed increase in insect invasions. Air transportation facilitated international tourism and the trade of certain insect-associated commodities, including freshly cut flowers53,56. Horticultural and ornamental plant trade has been identified as one of the main pathways for non-native insect introductions57,58,59. The transport of plants, and with them plant-feeding insects, is probably the reason why non-native herbivorous insects are over-represented compared to fauna, as well as why their relative proportion among non-native insects is continuing to increase whereas that of other trophic groups such as predators and detritivores is experiencing decline60.

In addition to shifting introduction pathways, new infrastructure for trade and transport can accelerate invasions. For example, the construction of the Suez canal (1869) and the Panama canal (1914) led to a major increase in marine biological invasions61,62. Although the analytical focus so far has been on marine invasions when considering the effect of these pathways, ships moving via these new routes almost certainly transported many insects and other stowaway organisms. By extension, China’s investment in new ports and infrastructure (such as the Belt and Road Initiative63) and the opening of trade routes due to climate change (including the Arctic trade route64) are highly likely to facilitate new invasions.

Since the 1800s, at least 6,700 non-native insect species have been recorded as established worldwide1, although this is likely to be an underestimate and actual numbers are estimated to exceed 10,000 species65. Global biological invasions do not currently show signs of slowing down4 and are even accelerating in Europe66. Despite growing accessibility to big data through initiatives such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), global trends in the post-2000s in insect invasions remain largely unknown.

Geopolitical events influence introductions

Invasion rates are rising globally, but on a regional scale these rates can be variable. Geopolitical events can both facilitate and disrupt the movement of species through direct introductions or by affecting international trade openness. For example, the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union have been implicated in the massive spike recorded in insect invasions throughout Europe66. Conversely, the Cuban Revolution decreased plant introductions in Cuba compared with other Caribbean islands, by reducing tourism and international trade67. In China, the expansion of commercial activities and tourism has been linked to the accelerating spread of non-native insect species68.

Armed conflicts can reduce biological invasions because of decreased international trade flows, but wars can also favour biological invasions69. For example, insects were accidentally introduced to the Americas and Europe as contaminants in wartime supplies69. Non-native species were also intentionally introduced through agroterrorism regimes in World War II and the Cold War, such as the fungus Aspergillus that can disrupt harvest yields69. The French and German governments also had breeding programmes for at least 15 insect species with capacity to inflict agricultural damage. Furthermore, armed conflict can also accelerate biological invasions through habitat disturbance, thereby leading to more opportunities for invasions and spread69.

Spatial patterns of insect invasions

Non-native species are not homogeneously distributed across the world and intercontinental species flows are asymmetric between donor and recipient regions, resulting from unequal globalized trade routes and complex introduction pathways. As a result of these global exchanges of non-native species, assemblages are homogenizing, particularly on islands.

Complex introduction routes

Introduction routes of non-native insects frequently include recurrent jump dispersal, multiple introductions from the native range, admixture and sometimes back-introductions into native ranges42,70, and often include bridgehead effects71. Secondary introductions across multiple insect species can originate from non-native populations rather than the native ranges. Evidence for this process comes from interceptions at ports or airports, originating from the invaded range of the species rather than from their native range. For example, the proportion of secondary interceptions of ants in the USA and New Zealand that came from invaded regions was 75.7% and 87.8%, respectively72, whereas the proportion of secondary interceptions of ants was 36% in the Taiwan region73. Similarly, among interceptions of non-native termites in the USA, 46% were secondary interceptions74. Border interception data indicate that secondary spread is a key feature of the establishment and distribution of non-native species. A potential mechanism to explain the success of the bridgehead effect is the evolution of enhanced invasiveness (that is selection for traits increasing spread) in the bridgehead populations71. However, there is only limited evidence that the success of a bridgehead population is due to adaptive evolution in the non-native population leading to greater invasiveness75. Another possibility is that the bridgehead populations were established in well connected trade or transport hubs, thereby facilitating secondary spread. However, the location of these hubs could change as global trade networks change according to altered commodity demand or geopolitical events.

Global species flows and distributions

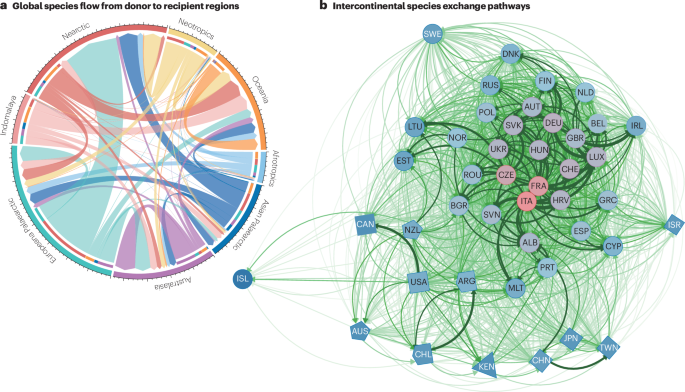

Pairwise species flows from donor to recipient regions for non-native insects have been established for general insect assemblages2,76,77, for ants78,79 and for beetles80. These associations indicate that intercontinental exchange among regions exhibits invasion asymmetry77, with some donor regions being over-represented relative to others. For example, the European Palaearctic has been an important exporter of non-native insect species2,81 (Fig. 3a). The greatest flow was from the European Palaearctic to the Nearctic81,82, but flow in the opposite direction from the Nearctic to the European Palaearctic was much smaller76. However, such global flows reflect the complex patterns of supply and demand, which are not static; for example, trade patterns shifting towards the Southern Hemisphere, or the development of countries or regions into global superpowers. These changing global balances among trading partners reorganize the global trade network83, inevitably changing invasion asymmetries, and potentially overshadowing Europe as a species donor.

a, Global species flow from donor to recipient biogeographical regions. b, Spatial network of species exchange pathways. Countries or regions are shown as nodes (shapes correspond to different continents), with their labels corresponding to the ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 codes. Intercontinental species exchanges are asymmetrical, and well-connected trade and transport hub regions have a central role in the networks of global insect spread (the pinker the colour, the more central a node is in the network (the more species it shares with other countries)). Data for panel a are from ref. 2. Panel b reprinted from ref. 85, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Importantly, species flows between donor and recipient regions can misrepresent true introduction routes, which frequently include multiple sequential introductions via bridgehead populations. Accordingly, these interpretations of global species flow might be distorted by the bridgehead effect, as demonstrated by the secondary interceptions of ant species flows to the USA78. To account for complex species flows, researchers are now dedicating more attention to understanding the role of networks in the spread of non-native species84. Using first recordings of 3,702 non-native insects and a sequential pattern mining approach, a hierarchical spread has been identified, with Italy and France acting as central hubs for insects before onward dispersal (Fig. 3b). Targeting countries identified as central hubs for improved biosecurity measures could have cascading effects on the spread network of non-native species, thus reducing biological invasions85.

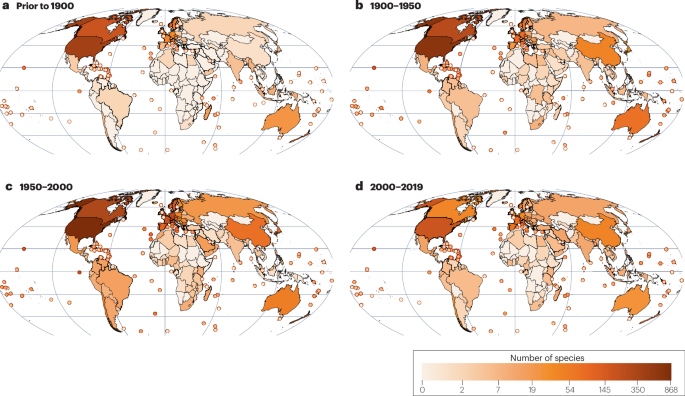

The species richness of non-native insects is largely unequal among countries and regions, with some, such as Europe, North America, Australia or New Zealand, being more invaded than others over the past centuries. Similarly, increases in invasions to South America, China and tropical Asia have been identified in the twentieth century (Fig. 4). This disparity is in part a consequence of asymmetric species flows from donor to recipient regions.

a–d, The cumulative number of established species for the years prior to 1900 (a), between 1900 and 1950 (b), between 1950 and 2000 (c) and between 2000 and 2019 (d). Hotspots of insect establishment before 1900 include North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand, mainland China and Japan since the 1900s, and several South American regions and tropical Asia after 1950. Data for all panels are from ref. 4.

Drivers of global species flow and distribution

The asymmetry of species flows between donor and recipient regions is due to several key drivers that seem to vary in important ways. Propagule pressure has been considered the principal driver of non-native species establishment86, yet there is mixed evidence for international trade (a proxy for propagule pressure) as a driver of global insect flows. For example, cumulative trade was the most important factor in explaining bark beetle (Scolytinae) species flows among six biogeographic regions (the Nearctic, the Neotropics, the Palaearctic, Indomalaya, the Afrotropics and the Austro-Pacific)80. However, when all the insects of three world regions (Europe, North America and Australasia) are considered, neither import value nor species source pools influence global flows, indicating that historical plant introductions might be more important76.

Differences in the species pool size of the donor region could influence species flows. In bark beetles, historical movement of non-native species might have depleted the availability of new species source pools in the native range86, which can slow the accumulation of emergent non-native species in the future87. However, the depletion of source pools of candidate species that might be introduced in the future seems to be much slower in insects than in other taxa (including other invertebrates, birds, mammals, vascular plants and fishes)87.

Another driver influencing species flow is the environmental conditions in the destination region, which help to determine the success of species establishment. Climatic similarity between native and non-native areas has been identified as a key factor determining the size of species flows within a global insect sample88, because climatic conditions strongly influence the capacity of a species to survive and reproduce in a given area.

Non-native plant diversity also shapes global patterns of insect invasions, and this relationship has persisted through time89,90. The flow of insects in the modern day is well predicted by plant flows from more than a hundred years ago (until 1900), which is a more substantial predictor than general trade flows2. The establishment of non-native plants creates the necessary pre-conditions for the invasion of many insect species that reassociate with their host plants from their native range90.

Finally, given that biological invasions involve multiple stages, including transport, introduction and establishment91,92, the dominant mechanisms at different stages might vary. By making this assumption and mapping the insect global flows at the transport and establishment stage of the invasion process, transport flows have been shown to correlate with the economic status and global purchasing power of recipient countries, whereas the flows of established insects are also influenced by the biogeography of recipient regions78.

The spatial patterns of non-native insect species richness at a global scale cannot be explained by differences in country or region size or climate, but instead are largely driven by socio-economic factors. Non-native insect species richness is greater in countries or regions with high gross domestic product (GDP)93,94,95, high national wealth and population density96, or with a high KOF index of globalization93, than in those with lower metrics. The KOF index is a composite index measuring the global connectivity of a country in terms of economic and information flows, cultural proximity, social contact and political engagement, and it therefore integrates various dimensions of globalization97. Global trade and transport are known to facilitate insect invasions by increasing propagule pressure77,92 and are therefore important determinants of non-native insect distributions98. In particular, countries that were more connected through trade networks for multiple commodities tend to receive more non-native insects than those highly connected for fewer commodities98. In addition to socio-economic activities shaping the global movement of non-native insects, the presence of non-native plants is another factor that is important in determining the probability of establishment90. At large spatial scales, non-native insect species richness is driven by both native and non-native plant species richness89. Thus, although propagule pressure is widely recognized as an important driver of insect invasions, the availability of suitable host plants is also a major determinant of non-native insect distributions90.

Homogenization of species assemblages

Owing to the global spread of non-native species, insect communities worldwide tend to become increasingly homogenized. This pattern has been particularly pronounced and is well studied in ants, whose assemblages are becoming increasingly more similar across different regions, especially on tropical islands99. Before the spread of non-native ants, species assemblages that were geographically closer were typically more similar99. However, the decline of similarity with increasing geographic distance is weakened with the global spread of non-native ants99. Consequently, the boundaries of historic bioregions, which are characterized by sudden changes in community turnover resulting from millions of years of evolution and natural dispersal limits, are eroding because of insect invasions99. Global biotic homogenization has also been found in plants100 and terrestrial gastropods101, but a global analysis for other insect groups is still lacking. On a more regional scale, biotic homogenization has been observed in insect communities of the Southern Ocean Islands, resulting from the establishment of non-native species102.

The homogenization of landscapes, and in particular cultivated plants, might also favour the homogenization of herbivorous insect communities feeding on them. Forestry and agriculture rely on a small pool of species that are cultivated globally, vastly increasing the opportunity for the homogenization of insect pests among regions103. However, these observations are limited to a small subset of insect biodiversity. Further research is required to measure the effect of host plant homogenization on the similarity of insect communities.

Homogenization can also occur at a finer spatial scale. In coastal California, the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) homogenizes ant communities by displacing native ant species that forage above ground104. Similarly, ant communities invaded by the fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) show greater trait redundancy, resulting in functional homogenization at the landscape scale105. Urbanization can also exacerbate homogenization patterns by favouring non-native insects. For example, urban areas in Quebec favour a few abundant non-native butterflies while native species richness is reduced, leading to more homogenized butterfly communities in urban compared with rural habitats106.

Future invasions

Future insect invasions can be predicted in space (for instance, identifying areas that are expected to accumulate many new non-native insects based on current invasion debts) and in time (for instance, estimating rates of change in invasion dynamics).

Predicting invasions using trade metrics

The history of biological invasions clearly demonstrates that connectivity via trade is a major driver of species transfer among regions53,56,92. Therefore, invasion science can use these human activities to predict new invasions1. A correlation of the number of non-native species per country or region with GDP, with population density or with the extent of human footprint on the environment provides an indication that human activities are linked to the overall level of invasion107,108,109,110. However, these proxies of trade are heavily generalized and are poor predictors of new invasions111. General proxies of trade have also been used to assess the relative importance of trade compared with environmental factors in shaping the distributions of non-native species, with conflicting results. Trade (or a related socio-economic proxy) has been flagged as either the most important driver of invasions96, as an important factor among others112, or even as not linked to invasion patterns at all113.

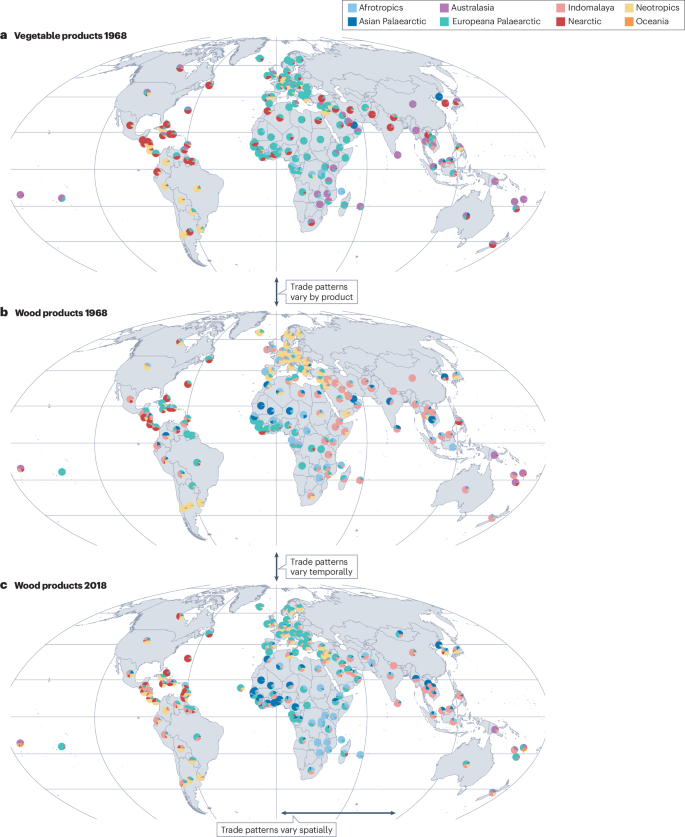

There are several possible explanations for these inconsistencies in the importance of trade to species invasions. First, time lags between current species flow and past socioeconomic indicators could obscure the link between species flows and trade114,115. The contemporary distribution of non-native species is better explained by historical rather than by current human activities115. Second, determining the importance of trade can depend crucially on using relevant metrics of trade. Different commodities can have very different global trade networks (Fig. 5). Moreover, linking trade with invasions is complicated by the fact that specific countries can change trading partners over time15 and that trade networks vary in space, with different countries using different trading partners to import the same commodities (Fig. 5). These patterns illustrate the complexity of using trade flows to predict invasions: because researchers need to determine the relevant commodities, the time span and the spatial focus of their data to be able to use trade data to understand or predict future invasions of specific species, it might be necessary to have prior knowledge about the biology of a particular taxonomic group and its propensity to be associated with different commodities116. For example, flows of ants to the USA are linked to trade in plants and fruits (which from import–export interception records are known to transport ants) but not to agricultural or general trade117. However, it is unknown whether such specificity is the rule and whether specific metrics of trade are needed to predict future invasions of particular insect species, or to build risk assessments for focal countries. This understanding would be particularly valuable in the light of ongoing globalization, with emerging economies opening up markets and changing trade networks15.

a, Global vegetable imports in 1968. b, Global wood imports in 1968. c, Global wood imports in 2018. Pie charts show the proportion of imports originating from each continental region. Each map depicts the geographic origin of trade imported by country. Trade flows can vary by commodity (a and b), by time (b and c) or by space (c). Data for all panels are from the United Nations, downloaded using the ‘tradestatistics’ R package147. Administrative borders of countries are from the Database of Global Administrative Boundaries (GADM 4.1) (ref. 148).

Predicting future invasions based on current trade networks is further complicated by transport technologies shifting towards greater speed and efficiency, reducing the time spent in transit and increasing the survival probability of hitchhiking insects in the absence of concomitant advances or investment in monitoring or mitigation53. Finally, novel introduction pathways are continually emerging. For example, insects have risen in popularity as exotic pets and are now traded in online stores and shipped by post19. If this deliberate movement of insects becomes more widespread, invasions resulting from accidental escapes after intentional introduction could become an important, if unexpected, pathway of spread.

Invasion debts

Although current socioeconomic activities and transportation are causing new invasions, past activities have also caused important invasion debts115. One reason for these debts is the long time lag between establishment and discovery of the non-native species. Some species have been introduced in the past but go unnoticed for decades because they are small and inconspicuous, or because they have not yet reached the critical population size required to cause noticeable effects118. It is estimated that 20–40% of established non-native insects remain undiscovered119.

Invasion debt captures the reality that many non-native species have not yet been detected or have not yet caused any discernible effects. In addition, many species are transported around the world, as is evident from border interceptions, but have so far failed to establish outside their native range120. This failure to establish could, in part, be attributed to the absence of suitable host plants. Many insects are specialist herbivores121 and depend on host plants from their native range for their establishment. As plants are introduced to more regions worldwide, they form new niches for insects, creating the conditions required for insect establishment90. On a global scale, some world regions (particularly tropical Asia and Africa) have imported many non-native plants but have not yet observed the non-native insects associated with them2.

Global acceleration of invasions

Based on modern invasion dynamics and the size of available species pools, models of the future accumulation of non-native insects until 2050 predict further accelerating global spread122. The world regions in which non-native insect richness is predicted to increase most over the next decades are Europe, temperate Asia and North America122. Remarkably, this future acceleration is possible because the pool of potential insect invaders has not yet been depleted. As globalization continues to move new species around the planet, an increasing number will establish in regions outside their native ranges4.

Possible mitigation

Despite the long history of the intentional and unintentional movement of species, there is little evidence of efforts to limit global anthropogenic spread of organisms prior to the twentieth century123. The existence of non-native species was recognized in various parts of the world in the nineteenth century124,125,126, including occasional reference to their status as pests127. In 1878, the grape phylloxera conference in Bern, Switzerland, led to the first international phytosanitary agreement in recognition of threats due to a non-native plant pest, the North American aphid (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae)128. A few decades later, the United States Plant Quarantine Act of 1912 created the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service as an arm of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), with the power to regulate the movement of harmful non-native species. This act stands in stark contrast with the numerous acclimatization societies popular in Europe and America in the mid- to late 1800s128, and with the charter mandate of the USDA “to procure, propagate and distribute among the people new and valuable seeds and plants”129.

Preventing biological invasion via manual inspection of imports is a daunting task as global trade volumes have grown dramatically. Inspection is difficult, expensive and is often inadequate, with high rates of slippage53. Most countries use a black-listing approach, where only species previously identified as potentially harmful and/or likely to establish are denied entry130. Several countries have proposed white-listing (where only species deemed acceptable by formal risk assessment are permitted entry) and/or grey-listing approaches (where pre-identified watch-list species are denied entry pending assessment). However, such policies have been challenged under World Trade Organization rules131, and stricter import regulations (as seen in New Zealand and Australia) have not successfully prevented the arrival of some high-profile biotic threats, including myrtle rust (Puccinia psidii)132. In addition to inspection, considerable effort has focused on shutting down pathways of non-native pest invasion133. In 2022, the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) adopted ISPM 15, a binding rule among signatory countries requiring bark removal as well as chemical or heat treatment of wooden shipping pallets, a known pathway for the spread of non-native bark and wood-boring insects. Although apparently effective in reducing interceptions of these insects, concerns about compliance and efficacy persist, prompting some importers to favour processed or non-wood alternatives134. Other major pathways of introduction, notably those linked to the horticultural trade, have so far proved more difficult to manage via national or international regulation, despite clear evidence of their role in the spread of non-native species among regions59.

Other prevention or mitigation approaches have gained traction in recent years. The planting of sentinel gardens and targeted monitoring using biological attractants (such as insect pheromones and plant stress kairomones) as part of an early detection rapid response network both offer the potential to detect nascent invasive insect populations135,136. Technological approaches are also in development for monitoring and mitigation purposes. For example, passive sampling of air or water coupled with rapid sequencing of environmental DNA has potential to aid in the detection of non-native species, particularly as sequence databases, bioinformatic pipelines and high-throughput sequencing platforms continue to improve137. Detection of insects via machine-learning-enabled visual, chemical or acoustic monitoring is receiving some focus in biosecurity interceptions or around ports of entry, although such technologies are still largely in their infancy or are tailored to only a small subset of species138. Distributed citizen science initiatives such as iNaturalist, EDDMapS or WildSpotter have been successful in mapping species distributions by voluntary contributors using smartphone applications138,139. Improved databases and algorithms for automatic and accurate detection of new potential non-native species are powerful tools against established non-native species, although early detection or prevention will require improving research facility infrastructure and technological tools to create portable field-ready devices without automated identification capacities138. Finally, web crawling or scraping to detect and mitigate the online trading of living organisms140 can be useful, facilitating data capture and/or promotion of public awareness via social media platforms. Other mitigation strategies include crowdsourced inspection for the detection of non-native species, either at ports as an outsourced arm of existing inspection agencies or via distributed, web-enabled sensors around the world. These all represent plausible avenues for the mitigation of biological invasion in the years and decades to come138,139.

Summary and future directions

Several thousand insect species have already established in areas outside their native range and many more are predicted to arrive in the near future, threatening biodiversity and human livelihood1,2. The spread of non-native insects on a global scale has been influenced by multiple facets of globalization, including geopolitical events in history such as wars and economic crises52, the types of traded product117, and the topology of trade and mobility networks84, and by technological innovations such as steam ships, containerization and the internet1. This complex multitude of aspects of change demands a much better understanding of how precisely these socio-economic aspects influence invasions70. Direct evidence of spread, particularly of causal links between invasions and globalization, is not always clear. Challenges lie in identifying the most pertinent indicators of globalization to predict invasions, given that many metrics of trade and connectivity can vary in time, space and by type of commodity (Fig. 5). Overall, there is a substantial body of literature indicating the importance of a better understanding of human-mediated transport of insects1,53,141, a necessary starting point for predicting and preventing future invasions. More interdisciplinary work among invasion biologists, ecologists, entomologists, economists, data scientists, social scientists and archaeologists, among others, is essential for this field of research to progress. Here, we suggest key future directions of research for the field to develop a better understanding of the temporal dynamics and spatial patterns of insect invasions.

Obtaining evidence of the earliest human-mediated movements of insects is particularly important to characterize how human history has shaped the distributions of insects worldwide13. Research focusing on insects found in archaeological sites worldwide would improve our understanding of the early dispersal of insects. Currently, the evidence is limited to a few well studied sites and species. Targeted efforts to develop more comprehensive evidence of prehistoric dispersal of insects or the role of the Roman Empire and the Spice and Silk Roads in large-scale dispersal of insects could inform a more nuanced understanding of invasion processes and dynamics. To this end, it might be possible to explore genetic tools for analysis of ancient DNA to reconstruct these early dispersal routes142,143. To explore insect dispersal over the past two hundred years, it will be important to improve the current datasets of first records of early observations. Despite the growing importance of these datasets, many records remain buried in the scientific and grey literature and are not yet accessible for analysis.

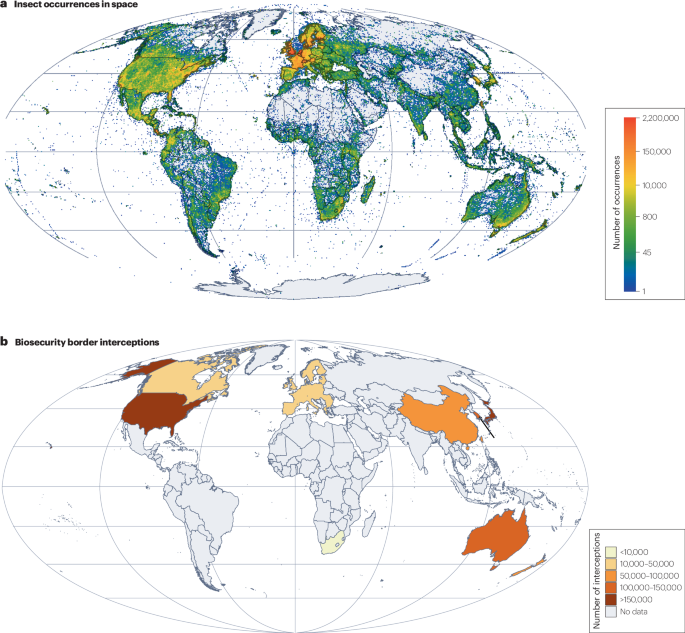

The insect dispersal dynamics leading to present-day distribution are of the utmost importance for characterizing the state of insect invasions now and for predicting future invasions. We suggest that it will be fruitful to explore emergent tools such as data mining of social media websites (such as Instagram) and community sources (such as iNaturalist) where the public can enter observational data for different species144,145. These data can be usd in fundamental and applied research to build models for the early detection of accelerating invasions that could in turn be used to prioritize mitigation efforts. Moreover, it is important to improve and better standardize sampling efforts, which are highly heterogeneous worldwide, with some regions still poorly sampled146 (Fig. 6a). Further key questions include which commodities transport which insects, how specific the association between insects and their transport vectors is117, and what the time lags between introduction and detection are for different taxa118. To address these questions, more extensive databases of border interception data will be useful, as they provide insight into ongoing species transport120 (Fig. 6b).

a, Recorded occurrences of insects (both native and non-native) in space. b, Number of border interceptions by biosecurity services per country or region. The spatial pattern of known insect occurrences reveals geographic gaps in our understanding of the transport stage, reflected by border interceptions, with particular scarcity in South America, most of Africa, the Middle East and large parts of South and Southeast Asia. Data in panel a are from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (ref. 149). Data in panel b are from refs. 120,150,151.

Overall, the field of invasion science is still young. Despite progress in building large datasets and analysing global patterns of insect invasions, important geographic knowledge gaps remain (Fig. 6). Disentangling relevant socio-economic factors is not straightforward and the importance of specific geopolitical events, including European colonialism and early trade routes, is still uncertain. We believe that the field of invasion science will make substantial progress in the near future, thanks to increasing interdisciplinary collaboration.

Responses