A case for assemblage-level conservation to address the biodiversity crisis

Introduction

Conservation professionals and natural resource managers are challenged with the daunting task of protecting species and ecosystems in an era of rapid environmental change in which historical benchmarks offer little guidance1,2. Efforts to conserve biodiversity, often motivated by environmental laws, have historically focused on the recovery of species, subspecies or populations3,4. Ecosystem management emerged in the 1990s5,6,7 as a practice focused on sustaining biological and ecological functions such as hydrologic cycles, soil fertility and food webs8,9. Although actions taken under this ‘ecosystem-level’ approach to conservation might have coincidental benefits for individual species, the goal of the practice is to improve conditions at the ecosystem scale.

Conservation interventions that are aimed either at species or ecosystems have been pivotal to preventing the extinction of many species10, but these prevailing approaches alone are insufficient to address ongoing conservation challenges. Species-level conservation has been criticized for prioritizing the protection of high-profile species rather than overall biodiversity4,11, especially as the number of individual species needing attention is increasing. Conversely, ecosystem-level conservation must account for a complex array of species interactions, feedback loops and dependencies that can make goal setting and assessments of management action prohibitively challenging, and can lack the necessary life-history detail for effective conservation of at-risk species4,9.

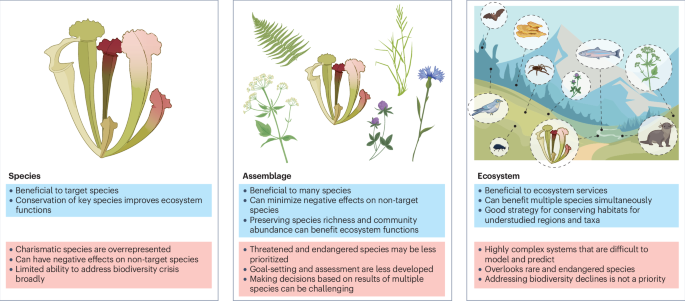

Conservation efforts focused on species assemblages — a level of ecological complexity between species and ecosystems — have been overlooked, yet are essential for addressing the global loss of biodiversity. The goal of assemblage-level conservation is to increase the occurrence, persistence or abundance of multiple species simultaneously, typically a group of taxonomically related species that co-occur in space12 (Fig. 1). Assemblage-level conservation approaches include: considering current and projected future distributions of biodiversity (such as species richness or phylogenetic diversity) in the spatial prioritization of protected areas13; modelling how multiple species in an assemblage might respond to a management action14; and creating climate-adaptation plans based on predictions of the future distribution or abundance of multiple species within an assemblage15. Although definitions of conservation biology from the 1980s emphasized ecological communities16, data limitations and statistical shortcomings limited the extent to which conservation action could focus on multiple species. Rapid growth in multi-species data17, computational power and advances in statistical modelling18,19,20 now present ideal conditions for a shift towards assemblage-level conservation.

Single-species conservation focuses on the goal of increasing the occurrence or abundance of a single species. Assemblage-level conservation aims to increase the occurrence or abundance of multiple species that co-occur in space. Ecosystem-level conservation concentrates on preserving ecosystem services provided to humans. We note that many conservation interventions can have outcomes that apply at each of these levels. Each approach has strengths and weaknesses that are briefly summarized.

In this Perspective, we call for an assemblage-level approach to conservation that complements conservation strategies primarily centred on either single species or entire ecosystems, which we refer to as species-level and ecosystem-level, respectively. The primary distinction between species-, assemblage- and ecosystem-level conservation lies in the level of ecological complexity at which the conservation goals are articulated (Fig. 1). A given management intervention could achieve conservation goals at multiple levels, and assemblage-level conservation can be applied in conjunction with single- and ecosystem-level approaches. After discussing the advantages and disadvantages of each approach, we describe several types of conservation intervention or management action that can simultaneously improve outcomes for multiple species. We conclude by discussing promising data and modelling developments that could accelerate effective, multi-beneficial strategies for conserving both threatened and common species. We strive to inspire interdisciplinary collaboration between quantitative ecologists and conservation practitioners that enable the design, evaluation and improvement of conservation interventions at the assemblage level.

Species-level conservation

Species-level conservation has a well established methodological foundation4 and history of effectiveness in preventing the extinction of many species worldwide10. International policies supporting species-level conservation include the Endangered Species Act in the USA (1973), the Wildlife and Countryside Act in the UK (1981), and the Act on Conservation of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora in Japan (Act No. 75 of 1992). The recoveries of the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) in China21, the grey wolf (Canis lupus) in Europe22, the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) in the USA23, and several species of sea turtle globally24 are notable examples of successful conservation at the species level.

Policy and management initially intended to protect a single species can also lead to improved habitat for other species25,26 and even better ecosystem functioning if management actions lead to the recovery of keystone species27,28 or the removal of invasive species29. For instance, conserving a carefully selected umbrella, flagship or indicator species can sometimes provide benefits to many other species30. However, the application of umbrella species to protect broader groups of species has been limited in practice31. For example, the management of threats throughout the distribution of the Australian federal government’s 73 umbrella prioritization species is expected to benefit only 6% of its threatened terrestrial species31.

Although single-species conservation has been effective at preventing extinction, it has been less effective at aiding recovery. Most species assessed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) that had a status update between 2007 and 2023 showed status deterioration rather than improvement32. Similarly, few species listed as endangered by the USA’s Endangered Species Act have been subsequently delisted as a result of recovery33. Actions to promote species recovery require extensive biological information34 and causal understanding of processes underpinning declines4, which can be time-consuming to accumulate and unattainable for many species. Additionally, single-species conservation initiatives tend to provide reactionary solutions to prevent the extinction of species that have already faced large population declines. This use of resources can fail to address the ultimate drivers of the species’ decline35. Furthermore, failing to address declines in common species not categorized as threatened or endangered can have detrimental ecological consequences, because common species contribute many individuals and substantial biomass to ecological communities36. However, few conservation projects focus on preventing the decline of species that are currently abundant.

Another limitation of single-species conservation is that taxonomic biases are prevalent, with charismatic vertebrate species often receiving greater conservation attention than invertebrates or plants37. For example, the European Union funded the conservation of animal species at three times the rate of plants between 1992 and 2020 (ref. 38) The European Union’s financial investment in vertebrates through the LIFE (L’Instrument Financier pour l’Environnement) programme was six times higher than for invertebrates over a similar time period, with birds and mammals alone accounting for 72% of species and 75% of the total budget39.

Finally, species-level conservation actions rely strongly on species first being ‘listed’ by the IUCN Red List or provincial or federal governments. However, many undescribed species are probably vulnerable but have not been listed40. Ten times more species are thought to be at risk of extinction in the USA than are listed under the Endangered Species Act40. One in six species assessed by the IUCN are data-deficient41, and assessments of data-deficient species indicate that more than 50% of these species are probably threatened with extinction42. In summary, whereas single-species conservation strategies have demonstrated important successes, their limitations highlight the need for integrated approaches that consider broader ecological dynamics and multi-species dependencies to effectively protect biodiversity.

Ecosystem-level conservation

Ecosystem conservation integrates ecological and social information with the goal of safeguarding both biological resources (and their associated ecological services7,8) and benefits to humans, including food, energy, water, disease control, waste decomposition and opportunities for connecting with nature43. The application of ecosystem conservation has led to several noteworthy achievements in conserving biodiversity and improving ecosystem health. For example, efforts to control invasive plants in South Africa yielded substantial economic benefits by protecting ecosystem services in the form of water resources, grazing and biodiversity44. Conservation efforts at the ecosystem level, specifically restoration aimed to sequester aboveground carbon in deforested areas of the Atlantic forest, have also led to increased native plant diversity45. Environmental policies such as the Clean Water Act in the USA have been instrumental in recovering river ecosystems, which provide fresh water for humans, enhance recreational opportunities and ultimately increase native species diversity46. Advocates of this approach argue that, when implemented successfully, ecosystem conservation can provide cost-effective solutions to maintain healthy ecosystems and preserve biodiversity while also permitting sustainable development7.

Carefully implemented ecosystem management can benefit many species simultaneously and has value in protecting organisms and ecological processes in understudied habitats and for undescribed species5. However, it has been criticized for placing greater value on common or wide-ranging species than on rare, range-restricted, or keystone species, which also contribute to critical functions in some systems47,48. Conservation planning at the ecosystem level can lack the details necessary for the effective protection of rare, threatened or culturally important species4. For example, the removal of invasive grass to improve wetland function led to decreased foraging habitat and substantial declines in abundance of a federally endangered bird in California, the Ridgway’s rail (Rallus obsoletus)49.

Assemblage-level conservation

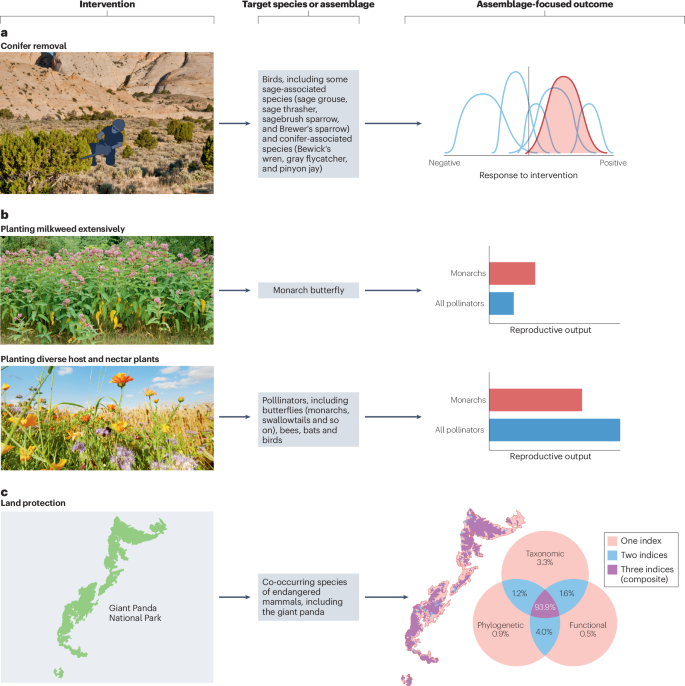

We now discuss an approach to conservation in which actions are taken to benefit multiple species simultaneously. We describe the ways that several common conservation interventions — habitat management, area-based conservation, climate-adaptation planning, and species assessment and recovery planning — can take an assemblage-level approach (Fig. 2).

a, Targeted removal of conifers in sagebrush ecosystems benefits sagebrush-associated bird species but can harm conifer-associated bird species. Prioritizing sites for conifer removal based on predicted average responses in the sagebrush-associated bird assemblage led to overall positive responses62. b, Planting diverse plants in gardens can benefit the monarch butterfly, a species of substantial conservation concern, while also supporting the wider assemblage of pollinators. Planting only milkweed, the monarch’s host plant, can benefit the monarch but does not support the wider community. The inset plots showing reproductive output are hypothetical, but illustrate results for monarchs from ref. 64. c, Protected areas have been established for the giant panda, but a wider range of co-occurring endangered mammals could benefit from enhanced management in the Giant Panda National Park. Photograph credits: JeffGoulden/Getty (a); karayuschij/Getty (b, top image) and the_burtons/Getty (b, bottom image). Panel c adapted with permission from ref. 70, Elsevier.

Defining assemblage-level conservation

Ecologists and conservation professionals have long been interested in assessing community dynamics, both in terms of understanding species compositions across time and space50,51 and interactions among species in assemblages52,53. We argue that this level of ecological complexity between single species and ecosystems is a tractable scale for implementing and assessing conservation interventions. Assemblage-level conservation often relies on measurements of biodiversity metrics (for example, richness, evenness, beta-diversity, functional diversity and phylogenetic diversity) and their changes over time and in response to conservation action. Conservation goals based on these metrics can include restoring richness and diversity; improving abundance trends for the greatest number of species; predicting the responses of multiple species in a taxonomic group to potential conservation action; and/or making management decisions with objectives for multiple species in mind. Examples of actions taken to achieve such goals include using controlled burns to reduce the effects of invasive species and to increase plant diversity in fire-prone ecosystems54, restoring wetlands to increase native bird species abundances55, and connecting and expanding urban gardens to support pollinator diversity56.

In comparison to the well-established history of setting and assessing progress towards single-species management goals57,58, the optimal methods of establishing assemblage-level management goals and incorporating assemblage-level metrics into management decisions are less refined. Multi-species recovery plans (in other words, a conservation recovery plan focused on more than one species) completed fewer conservation goals in Brazil than single-species recovery plans, attributed in part to multi-species plans being more ambitious and generated by larger teams of actors59. However, historical data and statistical limitations that have hindered assemblage-level conservation are quickly being addressed and multi-species risk assessments and management plans are now implemented more widely in conservation programmes60. For example, Australia has adopted procedures for listing ecological communities under their Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act61. Although these plans often focus on pre-selected groups of threatened species61, expansions of conservation plans that include larger assemblages of both common and threatened species can help to prioritize management actions before listing of a species is needed.

Habitat management

Individual species in an assemblage vary in response to conservation actions. Management prioritizing a single species typically provides the greatest benefit for that target species, but can sometimes negatively affect non-target species; explicit consideration of average assemblage responses can minimize these trade-offs or limit unintended consequences of management. For example, encroaching conifers are removed in sagebrush ecosystems (in the western USA) to benefit sagebrush-associated bird species including the sage grouse and Brewer’s sparrow, but conifer removal is harmful to pinyon–juniper-associated species such as the Pinyon jay62. Spatial prioritization simulations showed that selecting sites for conifer removal based solely on improving outcomes for the Brewer’s sparrow led to only modest projected improvements for other sagebrush-associated birds and to negative outcomes for conifer-associated birds62. However, selecting sites based on averaged projected responses to conifer removal among all sagebrush-associated birds improved the outcomes for multiple sagebrush-associated species, while simultaneously minimizing negative outcomes for conifer-associated birds62 (Fig. 2a).

Some management actions can benefit a single charismatic species in addition to the broader assemblages of which they are a part. The monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is a flagship species facing ongoing population decline63. Substantial efforts are made by gardeners to plant milkweed (Asclepias spp.), the plants used by monarchs as breeding habitat. However, pollinator gardens with a diversity of host and nectar plant species beyond milkweed attract and support myriad species of pollinators across multiple life stages, while still benefiting monarchs56,64 (Fig. 2b). In fact, monarchs laid up to 22% more eggs in mixed-species urban garden plots than in milkweed monocultures64. Mixed-species plots also supported a higher abundance of natural predators without negatively affecting the survival rate of monarchs to adulthood64. This example highlights that undue focus on the habitat needs of a single species (here, exclusively planting milkweed to support monarchs) prevents progress on conserving a wider ecological community (here, the broader pollinator community).

In some cases, the diversity metrics of one taxonomic group correlate with diversity metrics of another group; if one group is easier to monitor than another, a cost-effective approach to habitat management is to take action for one group and assume that those actions will have an ‘umbrella’ effect on another group. For example, wetland birds share habitat requirements with other wetland-dependent taxa, so sites selected for restoration to sustain wetland bird populations will probably benefit those taxa as well65.

Area-based conservation

To achieve the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s target for protecting 30% of the planet by 2030, far more land and water area needs to be safeguarded in the coming years66. Natural resource managers and policymakers must identify the locations where protection should occur or where management would be most useful, typically through spatial prioritization methods. Although spatial prioritization must already consider numerous trade-offs (such as balancing land use for species and human livelihoods), using assemblage biodiversity metrics in spatial prioritizations can identify where the most species could be protected67. Although conservation initiatives centred solely on flagship species can have unintended consequences, such as giant panda management leading to declines in large carnivore distributions68, a focus on assemblages can capitalize on efforts to protect land for flagship species69. For example, sites where a high diversity of endangered mammals co-occur with the giant panda can indicate where further protection and enforcement would be beneficial70 (Fig. 2c).

The widespread loss of natural wetlands bordering the Yellow Sea is contributing to large declines of migratory shorebirds in the East Asian–Australasian Flyway71. Tracking studies of migratory birds are improving the ability to effectively identify wetlands in the Yellow Sea that are important to multiple declining bird species72. The protection of migratory birds and their habitat represents a clear example of an assemblage-level conservation approach that has been adopted worldwide.

Climate-adaptation plans

To ensure protected areas can support biodiversity through time, it is important to select and conserve areas that have high biodiversity currently and are predicted to remain climatically stable under future climate scenarios73,74. Climate change is transforming ecosystems in ways that challenge traditional management approaches that are based on assumptions that future environmental conditions will reflect twentieth-century conditions. The resist–accept–direct (RAD) framework is a decision tool in which natural-resource managers consider how to respond to changing ecosystems in shifting climates. Specifically, the RAD framework encourages managers to expand their focus beyond the traditional emphasis on resisting change and prompts evaluation of whether accepting or directing change might be appropriate decisions15. Some forward-thinking applications of the RAD framework are now considering assemblage-level conservation actions. In Acadia National Park (northeastern USA), managers are using RAD to prioritize decisions for a tree community in which the majority of species are expected to lose climatically suitable habitat over the next 80 years75. Decisions about where to ‘resist’ invasive species encroachment are informed by spatially explicit community models, and decisions about how to ‘direct’ change are informed by ongoing experiments testing the capacity of transplants of more southerly deciduous hardwoods to establish populations in Acadia’s changing climate conditions75 (Fig. 2). RAD applications considering an assemblage instead of a single species ensure that managers can aim to preserve or enhance ecosystem function and resilience, even if some individual species are lost or replaced.

Multi-species assessments and recovery plans

The pace of human-induced biodiversity declines and extinctions, combined with the substantial resources required to evaluate species extinction risks and recovery plans, strains the ability of organizations to assess species quickly enough. As a result, some countries and organizations are now adopting multi-species approaches to status and recovery assessments60,76, improving efficiency by avoiding duplicate workflows.

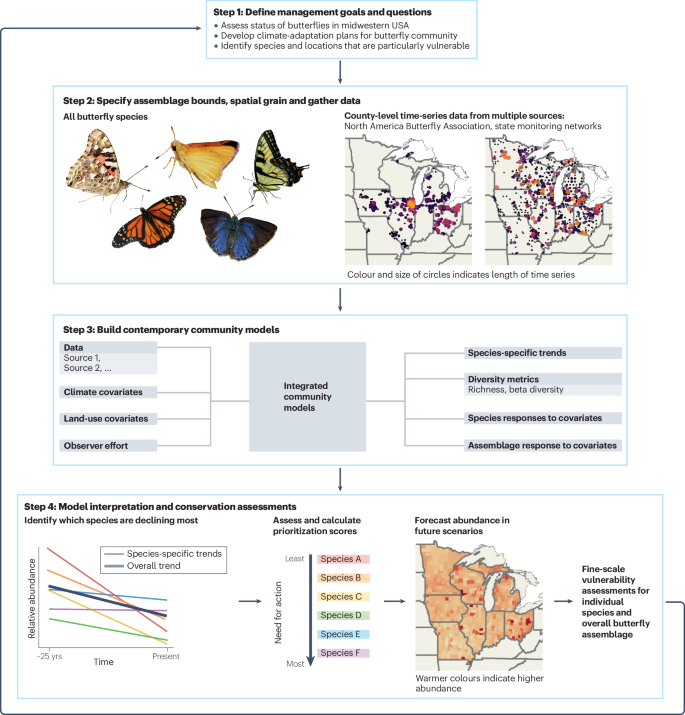

Multi-species assessments are particularly useful for identifying shared stressors and guiding management action to address shared challenges. The South Florida Multi-species Recovery Plan established in 1999 (ref. 77) recognized that an assemblage of 68 federally listed endangered species had shared stressors (namely habitat loss, invasive species and fire suppression) and thus shared specific recovery requirements. Multi-species assessments can also be helpful for species that are rare and difficult to monitor. For example, after a fungal disease (white-nose syndrome) caused severe population declines in many North American bat species, it has become difficult to quantify the status and trends for several hard-to-detect and now-rare species78. Acoustic monitoring and assemblage-level modelling approaches can help to inform management of these species by producing occurrence estimates of rare species even when data are sparse14. Crucially, community analyses such as integrated community models can improve estimates of population trends for data-poor species by drawing upon the signal of functionally similar, data-rich species18 (Fig. 3).

Interdisciplinary partners, including some authors of this Perspective, are collaborating to inform the conservation and management of butterflies in eight states in the midwestern USA. The collaboration is framed within a strategic habitat-conservation approach, an adaptive management framework adopted by the US Fish and Wildlife Service for making decisions about where and how to deliver habitat conservation effectively and efficiently to achieve specific biological outcomes. First (step 1), management goals and objectives are developed over multiple years in collaborative sessions with conservation experts, data stewards and statistical analysts. Second (step 2), after specifying the focal assemblage (136 midwestern butterfly species), abundance and species richness data at the county-level spatial grain are aggregated from multiple data sources (including several butterfly-monitoring programmes). Integrated community models leverage the strengths of data integration and hierarchical community modelling to generate precise estimates of species-level and assemblage-level abundance trends over time and space. Model extensions can include physiologically informed weather and climate covariates as well as changes in land-use metrics. Third (step 3), interpretations of these models can inform species status assessments, state wildlife action plans and endangered species listing decisions, thus helping to prioritize resources. Forecasts of diversity metrics can be used to identify areas that are projected to support diverse butterfly communities under future environmental scenarios. Fourth (step 4), model results can also locate areas where species richness or mean assemblage abundance are declining, helping to inform spatial landscape-conservation priorities. The process can be iterated when new data or research needs become available.

Hierarchical community modelling approaches have the distinct advantage of providing robust parameter estimates such as occurrence or abundance trends at both the species and assemblage level, readily allowing for status and recovery assessments (Fig. 3). Multi-species status assessments and recovery plans primarily focus on species that are already of conservation concern, which constrains the statistical benefits of hierarchical community models. Including both threatened and non-threatened species in analyses could not only improve the precision of model estimates, but also provides information on the average status and trends of species, encouraging proactive conservation interventions before legal protections, which can be economically costly and politically divisive, are required. Establishing a standardized protocol for reporting community models could encourage even wider use of these approaches in multi-species assessments.

Emerging data and models

The biodiversity data revolution — combined with rapid growth in computational power, development of improved molecular techniques and statistical advances — is rapidly expanding opportunities to enact conservation at the level of species assemblages. Until the past two decades, quantifying the dynamics of entire assemblages was not feasible because biodiversity data were generally collected by individual research groups and were thus limited spatially, temporally and taxonomically79. However, participatory science initiatives (such as iNaturalist, eBird and the Dutch Butterfly Monitoring Scheme), regional and national structured survey programmes (such as the National Science Foundation’s National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON) and the Rothamsted Insect Survey), and international data repositories to aggregate such data (such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)) are rapidly expanding the extent of community analyses and the resolution at which such analyses are possible. Diversity metrics derived from molecular data80 and participatory science81 are now available at repeated and reliable frequencies that allow for their use in conservation planning by tracking changes in populations, assemblage and threats over time.

Furthermore, new technologies for monitoring biodiversity such as environmental DNA82, automated acoustic monitoring83 and optical sensors84 are collecting data on more taxonomic groups than ever before, including overlooked groups such as invertebrates. In particular, environmental DNA and metabarcoding have the potential to increase the efficiency and accessibility of monitoring entire communities, even in groups for which taxonomy is poorly resolved17. Paired with robust statistical modelling and increasing computational power, these expanding data sources can uniquely contribute to evaluating the ecological dynamics of species assemblages and even entire communities at expansive spatial and temporal scales, paving the way for more informed, assemblage-level conservation strategies.

Modelling approaches such as hierarchical community models18,85 and integrated community models19,86 are uniquely suited for leveraging diverse ecological data sources to advance assemblage-level conservation. These models can estimate an array of ecological dynamics such as occurrence, abundance, survival and reproduction, including the effects of environmental covariates on these processes19,20. Additionally, these models can be used with a variety of data types, such as detection–nondetection and presence–absence data (namely, multi-species occupancy models86) or count and distance-sampling data (namely, multi-species abundance models19). Hierarchical community models are particularly useful at scaling conservation efforts from single species to assemblages because these models estimate the biological parameters of individual species and mean assemblage parameters simultaneously through assemblage-level distributions19,87 (Fig. 3). These models share information across species by deriving species-specific parameters as random effects arising from common, assemblage-level distributions with a mean that represents the average assemblage effect and a variance that explains the assemblage-level variation of species-specific effects85. Such models can improve estimates of single-species parameters by being derived from a distribution parameterized with data from all assemblage members, which can be especially useful for quantifying responses of rare species88.

The use of assemblage-level data in conservation planning has been hindered, in part, by the fact that diversity metrics can be heavily influenced by differences in methods (such as spatial scale or survey technique) and sampling effort across datasets. Methods such as species accumulation curves89 and richness estimators90 can account for these differences, but they are not process-based, do not preserve the identity of species and do not account for variation in detection rates across species and habitats91. By contrast, process-informed hierarchical community models can account for imperfect detection biases and are thus better able to distinguish ecological signals from statistical noise. Unlike other approaches, hierarchical community models also propagate uncertainty throughout model levels. Evaluating uncertainty in parameter estimates is a key component of conservation decision-making techniques such as stochastic dominance, which incorporates ecological uncertainty into rankings of alternative conservation actions by comparing the probability distributions of their outcomes92. Integrated community models are extensions of hierarchical community models that integrate data of multiple types and sources19,86. For example, these models can integrate the spatial breadth of presence-only data with high-quality mark–recapture data to enhance statistical inferences of species and community dynamics. By propagating uncertainty throughout model hierarchies and accounting for detection differences across taxa, modern community models unlock potential to integrate disparate datasets and ultimately allow for better identification of locations and species in need of intervention.

Conservation policy at the assemblage level

Assemblage-level conservation offers advantages compared to species and ecosystem conservation approaches but has thus far had limited use in conservation policy. However, advances in assessing the threat statuses of ecological communities61 are likely to encourage the adoption of assemblage-level conservation. Policies enacted in Australia (in 1999) and in Germany (in 2006) aim to protect native species assemblages and communities of flora and fauna, respectively93,94. At present, ecosystem-level risk assessments such as the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems rely heavily on assemblage-level metrics to quantify an ecosystem’s status95, highlighting both the strengths of assemblage-level assessments and its nascent potential to direct policy and management decisions towards effective and efficient solutions to the biodiversity crisis96.

Environmental and natural-resource policy provides an opportunity to incorporate assemblage-level analyses into planning and management processes. Status and risk assessments, determining conservation targets to guide management priorities, and evaluating the broader effectiveness of management actions could all benefit from adopting assemblage-level conservation approaches. Assemblage-level assessments can add value to existing species-specific policies and laws, greatly improving the quality and breadth of information to understand threats, risks and optimal interventions. Additionally, diversity metrics could serve as a strong unifier of species- and ecosystem-based policy frameworks, maximizing the strengths of assessment and protection at both levels, and extending the benefits of conservation to a broad suite of taxa and ecosystem services in ways that improve efficiency, cost, scalability, response time and the ultimate probability of success. By incorporating assemblage-level conservation, policymakers can complement and strengthen existing policies, preventing biodiversity loss across multiple levels of biological organization and help to identify timely and efficient interventions before species reach threatened or endangered status.

Outlook

We make the case that conservation efforts focused on the assemblage level might be able to deliver conservation gains that both species-level and ecosystem-level conservation cannot achieve. Our goal is to inspire more efforts to develop effective, multi-species conservation strategies to protect both threatened species and ecosystem functions.

We recommend the continued use of community modeling to provide insight into multiple species-specific responses along with assemblage-level responses. Hierarchical community models can inform management across spectrums of ecological complexity, both at the species level where most funding is allocated, and at the assemblage level where scientific interest and data availability are rapidly increasing. To ensure the utility of hierarchical community models in informing conservation decisions, it is critical that species assemblages are determined by shared habitat requirements, functional traits or threats. Careful grouping of species based on study objectives and biological understanding of assemblages will ensure that parameter estimates for data-poor species are biologically informed97.

In addition to the continued development of community models, numerous research opportunities exist to facilitate assemblage-level conservation efforts. Experimental approaches are particularly valuable for identifying the mechanisms that dictate ecological systems and determining how to manage environments to achieve targeted conservation outcomes98. Carefully designed experiments comparing management treatments with controls can reveal the causal effects of management actions, increasing the scientific evidence available to inform decision-making. By integrating experimental approaches with modern ecological models, researchers can create efficient and reliable solutions to assemblage-level conservation challenges99. Such an integrated framework is especially beneficial for guiding interventions at small spatial scales, where assemblage-level data are often limited (unless aggregated to coarser spatial resolutions). Continued investment and refinement in new technology and methodology for biodiversity monitoring (such as environmental DNA, acoustic monitoring and optical sensors) has the potential to fill data gaps at finer spatial resolution than traditional monitoring methods. Another applied research area that spans assemblage- and population-level approaches is identifying management actions that can conserve and restore species interactions52,100. At present, few conservation-oriented studies at any level explicitly consider species interactions52,100 and modelling interactions in diverse ecological communities traditionally requires prohibitively complex models and large datasets. However, modelling advances have demonstrated promising applications to efficiently fit complex models of species interactions even with sparse data101.

Realizing the full potential of conservation at the level of species assemblages requires a concerted effort to build strong, interdisciplinary collaborations that encompass expertise in biology, modelling and management. By embracing assemblage-level strategies, conservation practitioners can develop robust, adaptive and inclusive management plans capable of addressing the complex and interconnected challenges facing biodiversity.

Responses