A comprehensive dataset of magnetic resonance enterography images with intestinal segment annotations

Background & Summary

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is one of the most challenging diseases of the 21st century, affecting >10 million people worldwide. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), encompassing Crohn’s disease (CD) and Ulcerative Colitis (UC), is a common complex digestive system disease with relapsing and remitting conditions that can be challenging to diagnose and manage. For instance, CD can affect the entire gastrointestinal tract, with a predilection for the terminal ileum and ascending colon, and is characterized by segmental and transmural granulomatous inflammation. CD diagnosis typically relies on a comprehensive evaluation of clinical symptoms, laboratory tests, endoscopic examinations, radiological imaging, and pathological tissue examination1.

Cross-sectional imaging has long complemented the endoscopic assessment of IBD. The patient underwent multiple follow-up examinations to monitor the condition and treatment effectiveness. However, endoscopic assessments are often burdensome for the patient2. Cross-sectional enterography techniques serve as a complementary tool to ileocolonoscopy, enabling the visualization of intramural or proximal small bowel inflammation in approximately 50% of patients with CD whose endoscopic examinations appear normal3,4. Thus, cross-sectional enterography plays a vital role in diagnosis and monitoring the disease course. Computed tomography enterography (CTE) and magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) have emerged as the most effective for imaging the small bowel to diagnose small intestinal CD in terms of detecting the extent of lesions and nature of luminal strictures, which helps assess disease distribution, staging, and detecting extraintestinal complications. Cross-sectional enterography can also be used to monitor treatment response, lesion healing, and disease progression5. In particular, MRE, with its excellent soft-tissue resolution and multiparametric imaging capabilities, has shown better performance2.

T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) is a crucial sequence for MRE in IBD, as it not only provides information about the anatomical structure of the bowels but also detects imaging signs such as bowel wall thickening, intramural edema, and bowel lumen strictures when the bowels are in good filling status. Furthermore, coronal T2WI allows for scanning of the gastrointestinal tract across the entire abdomen, allowing a more intuitive view of the intestinal segmentation and path.

However, the complexity of IBD, variable radiological manifestations of intestinal disease, differences in scanning techniques, and uneven levels of radiologists’ understanding of IBD imaging features combine to create challenges. The recognition of bowel segments from MRE images by radiologists can be challenging and time-consuming because of unclear boundaries, shape, size, and appearance variations, as well as uneven filling within the bowel. Consequently, accurate and standardized bowel segmentation is essential for the medical image analysis of IBD.

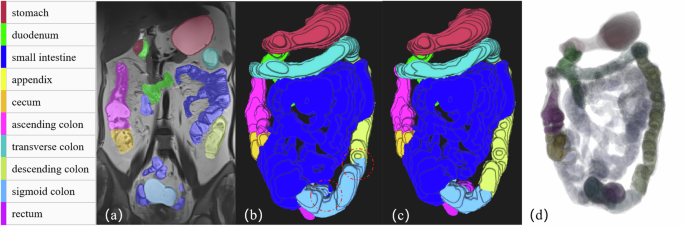

Deep-learning-based medical image segmentation has shown the potential to reduce manual effort and provide automated tools to assist in disease management. In recent years, a proliferation of deep learning-based methods has been proposed for the accurate and expedited segmentation of organs from abdominal CT volumes. However, the evaluation of these methods typically focuses on a limited number of organs. Although existing research have yielded commendable results in segmenting certain gastrointestinal tract segments, such as the liver, spleen, and kidneys, research specifically addressing intestinal segmentation remain scarce6,7. This issue often arises because the current studies tend to treat the entire colon as a single unit. However, this approach does not reflect real clinical scenarios because each segment of the colon has distinct functionalities (Fig. 1). By segmenting the colon into individual segments and simultaneously determining the position of the segment during the segmentation process, clinicians can conduct differential analyses of different segments, significantly enhancing the clinical utility and value of colon segmentation. The research gap in segmenting different intestinal segments stems primarily from the absence of a publicly available, large-scale, accurately annotated, and clinically relevant dataset for whole intestinal segmentation. Therefore, to advance intestinal segmentation research, it is crucial to develop high-quality task-specific datasets and establish benchmarks for this segmentation task.

An example of 10 gastrointestinal tract segments in an MRE. (a) T2WI MRE, (b) rough intestinal segmentation (primary prediction), (c) fine intestinal segmentation (physician-reviewed), (d) 3D visualization. T2WI, T2 weighted image; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; 3D, three-dimensional.

Furthermore, the complex structure and difficulty in delineating the entire intestine pose significant challenges. Although the academic community has access to CT data and segmentation methods for intestinal sections, there are no publicly available MRI datasets for full intestinal segmentation. This gap has resulted in the lack of research in this field.

In this study, we curated a real-world clinical MRI dataset and annotated the intestinal regions for segmentation. All scans in our dataset were meticulously hand-labelled, encompassing ten segments of the gastrointestinal tract. Collecting real-world clinical data is challenging and time consuming, primarily because of privacy and ethical considerations.

Additionally, we explored both fully supervised segmentation methods and annotation-efficient strategies to assess the benchmark performance on our bowel dataset. Specifically, we evaluated several cutting-edge medical segmentation models, including nnU-Net8, ResUNet9, UCTransNet10, and CoTr11.

Such a dataset would possess significant research value and could be utilized to evaluate and enhance existing whole-intestine segmentation methods, thereby establishing a benchmark for organ segmentation problems. Furthermore, this dataset could serve as an effective testing platform for the development of advanced whole-intestine segmentation algorithms, thereby making a substantial contribution to research in this field.

In summary, our work provides the following key contributions:

-

1.

We curated a unique, clinically focused dataset for comprehensive intestinal segmentation, comprising MRE data from 114 patients. This dataset offers a more detailed segmentation (10 intestinal segments) than previous studies.

-

2.

We established a new benchmark for whole intestinal segmentation, which includes (1) evaluating the effectiveness of currently available fully supervised segmentation methods and (2) quantifying the difference in segmentation capability between deep learning models and radiologists.

Methods

Cohort

Clinical and magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) data were retrospectively obtained from 114 patients with IBD admitted to the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University between December 2019 and May 2022. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board (approval number: 2022 [024]), which waived the requirement for informed consent.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: a) patients with a confirmed diagnosis of CD based on standard clinical, endoscopic, imaging, and histological criteria and b) patients over 12 years of age who had completed an MRE examination. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a) patients with incomplete clinical data or another concurrent intestinal disease, b) cases where MRI quality was insufficient for accurate observation, c) patients whose MR images did not include complete bowel segments, and d) patients who had undergone intestinal resection.

The population, images, and lesion profiles are shown in Table 1. The mean patient age was 33.67 (range, 12–74) years. There were more males (71.05%) than females. The location of the most severe bowel lesion was determined based on all MRE findings and was reported by experienced radiologists (L.H. and X.L., both with more than 10 years of experience).

MRIs

In this study, we retrospectively collected T2-weighted coronal magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) data from 114 patients with CD. Following the approach described in previous studies12,13,14, the patients underwent bowel preparation. Subsequently, they received 1600–2000 mL of 2.5% mannitol solution one hour before the MRI to fill the bowels. Additionally, 10 mg raceanisodamine hydrochloride (Minsheng Pharmaceutical Group, Hangzhou, China) was administered intramuscularly to the buttocks 10 min before scanning to inhibit gastrointestinal peristalsis. MR was performed using a 3.0-T MRI scanner (Magnetom Vida or Prisma; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) with a high-performance gradient system (maximum gradient = 80 mT/m, maximum slew rate = 200 mT/m) and two 18-channel phased-array coils, ensuring the quality of the abdomen MR image and a high signal-to-noise ratio. The details of the MRI acquisition parameters are presented in Table 2.

Intestines annotation

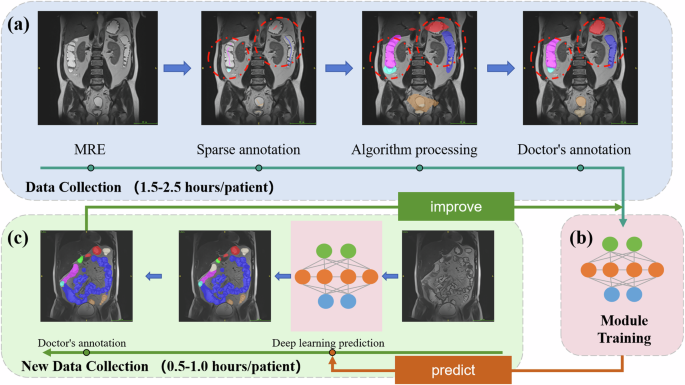

The intestinal images per patient were segmented into ten segments (0 to background, 1 to the stomach, 2 to the duodenum, 3 to the small intestine, 4 to the appendix, 5 to the cecum, 6 to the ascending colon, 7 to the transverse colon, 8 to the descending colon, 9 to the sigmoid colon, and 10 to the rectum), with fine pixel-level annotations performed by two experienced radiologists (X.W. with 3 years of experience and B.L. with 6 years of experience). All labels were delineated in the T2-weighted MR images using ITK-SNAP15 slice-by-slice in the coronal view using a pre-trained model for raw segmentation, which was subsequently refined by radiologists. The data annotation process is illustrated in Fig. 2. Subsequently, an abdominal imaging expert (L.H., with > 10 years of experience) carefully reviewed these annotations and resolved any disagreements through discussion, resulting in consensus annotations that ensured annotation quality. Finally, these consensus labels were released and used for subsequent model building.

Data collection procedure. (a) Initial Annotation: MRE data undergoes sparse annotations by doctors, algorithm processing for coarse segmentation, and final refinement by doctors (1.5–2.5 h/patient). (b) Model Training: The refined annotations are used to train a deep learning segmentation model. (c) Iterative Refinement: The model predicts segments on new data, which are corrected by doctors to further improve the model (0.5–1.0 h/patient).

The original annotated method is labor-intensive, taking 1.5–2.5 h per patient. To streamline this process, we first trained a deep-learning model using an initial batch of fully annotated data. This model was subsequently used to predict annotations for new MR data, resulting in more precise labels with minimal expert revisions and thus reducing the annotation time to 0.5–1.5 h.

Data Records

The dataset was hosted by Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/13839321)16. We made all the datasets described earlier available. They comprised 114 cases, each annotated with ten distinct labels corresponding to the abdominal digestive tract.

The data and corresponding label files are systematically named as “xx_data.nii.gz” and “xx_label.nii.gz.” In the label files, key anatomical regions—the stomach, duodenum, small intestine, appendix, cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum— were numerically labeled from 1 to 10 in sequential order.

Technical Validation

Experiment setup and evaluation metrics

In this study, all methods were implemented using the PyTorch framework on GPUs, including NVIDIA GTX1080TI, NVIDIA TITAN RTX, and GeForce GTX 1080 Ti. We selected nnUNet as the baseline for a fair comparison. nnUNet is a self-configuring segmentation framework that requires no manual intervention for data processing, training planning (network architecture, parameter settings, and so on), or postprocessing. It encompasses both 3D and 2D methods. Although nnUNet initially provided only a standard UNet implementation, we modified it to support additional network architectures. We used the default settings of nnUNet as our experimental settings, with a batch size of two for the 3D methods, 12 for the 2D methods, 1000 epochs, and a loss function combining cross-entropy and dice loss. All models were trained and tested based on these default settings, except that we did not use test-time augmentation owing to the extensive computational resources required—each model needed more than six GPU days to train, and each volume required more than five minutes to infer. We employed the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), a widely used metric, to evaluate the segmentation quality by measuring the pixel overlap between the gold standard and prediction. In image segmentation, the Hausdorff distance is highly sensitive to the accuracy of the segmented boundaries, whereas the Dice coefficient focuses more on the consistency within the mask’s interior. Therefore, we utilized the 95% Hausdorff distance (95Hd) to assess the quality of the boundaries in the image segmentation.

Evaluation of SOTA methods on the whole intestine dataset

Fully supervised learning is a fundamental and widely used approach for deep learning-based clinical applications, particularly in automatic multi-organ delineation systems. In this study, we explored several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods for our dataset, including nnUNet8, ResUNet9, UCTransNet10, and CoTr11. The quantitative segmentation results for DSC and HD95 are presented in Tables 3, 4, respectively. Results indicate that all SOTA methods can achieve promising results for large organs such as the stomach, duodenum, small intestine, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum (DSC > 77%). However, the segmentation results for the appendix and cecum are notably poor, with almost all methods achieving a DSC of <70% and HD95 > 20 mm. These findings suggest that segmenting large organs is a well-addressed problem given sufficient high-quality annotated samples from MRI images that offer clear soft tissue delineation. Currently, the image quality is sufficient to clearly distinguish large organs.

The challenge remains in achieving satisfactory segmentation results for small organs such as the appendix and cecum, even with strong soft-tissue recognition capabilities on MRI datasets. Limited research has focused on addressing these issues, and many datasets lack annotations for these small organs. Moreover, in our study, we distinguished the duodenum from the rest of the small intestine without further distinguishing between the jejunum and ileum. This is because the jejunum and ileum often do not have an exact boundary on MR Images, making accurate segmentation difficult. Identification of the terminal ileum is clinically significant for inflammatory bowel, as IBD lesions usually occur in the terminal ileum. This is one of the limitations of this study and a direction for future research.

Usage Notes

In summary, we introduced a meticulously annotated whole-intestine MRI dataset and evaluated several SOTA methods using this dataset. Our clinical research highlights the need for further improvements in model performance, particularly in small organs. We also identify unresolved technical and clinical issues that suggest potential research directions. The segmentation model database can be further utilized for the classification of intestinal MR signals and establishment of disease prediction models for IBD. It is clinically important to detect lesions in the corresponding intestinal segments of IBD, including automatic measurement of intestinal wall thickness and intestinal lumen diameter, automatic morphology fitting of the intestinal lumen, and qualitative and quantitative analyses of the presence of stenosis or penetrating lesions in the intestinal wall. In the future, we aim to expand our dataset to encompass a more extensive and uneven range of cases.

Responses