A Consensus Statement on establishing causality, therapeutic applications and the use of preclinical models in microbiome research

Introduction

The gut microbiota is composed of a cell-rich and diverse community of microorganisms inhabiting the gastrointestinal tract. Over the past two decades, the importance of the microbiota in biomedical research has been recognized due to their profound influence on human health and disease. Microbiota comprise bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea, and forms a complex ecosystem that interacts dynamically with its host, influencing various physiological processes and having a pivotal role in maintaining homeostasis1,2,3,4. Advances in sequencing technologies and analytical tools have enabled great insights into the composition and function of the gut microbiota, revolutionizing our understanding of its influence in health and disease5,6,7. Mounting evidence suggests that the gut microbiota is closely linked to numerous aspects of human health, ranging from metabolic regulation and immune function to neurological development and behaviour. Dysbiosis refers to altered composition, abundance and diversity of microorganisms in the microbiota that is causally implicated in the pathogenesis of acute and chronic diseases. This change in the microbial community can have a cascading effect on a variety of host functions8, including the immune and nervous systems, metabolism and intestinal barrier functions, thereby creating favourable or adverse conditions for pathogens and the commensal microbial milieu. Dysbiosis is causally linked to the development and progression of diseases, probably due to the disruption of beneficial interactions between the host and its microbiome, which is crucial for maintaining the health of the host3. Consequently, dysbiosis has been linked to conditions such as intestinal infections, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), obesity, liver diseases, cancer and even neurological conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD)9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Defining the exact nature of dysbiosis is essential for clinical and therapeutic applications, and requires a better understanding of mechanisms underlying the causal relationship between dysbiotic communities or single microorganisms and disease phenotypes.

In the past decade, there has been substantial development and increasing use of preclinical models such as organoids, gut-on-a-chip, and germ-free animal models aimed at better approximating or reflecting physiological conditions. These models also have the potential to establish cause-and-effect relationships within host–microbiome interactions, and establish the underlying mechanisms. Through a Delphi survey, we assessed the opinion of researchers and clinicians on the importance of preclinical models including the latest ones in inferring causality between alterations of the gut microbiome3 (that is, microorganisms and the products of their activities) and diseases, and in demonstrating the potential of microbiome-derived interventions as therapeutic candidates. Although preclinical models, such as animal models, organoids, and gut-on-a-chip systems, are valuable for screening and initial testing of therapeutics, it is important to note that human trials are essential for establishing the efficacy of these interventions.

Causality in the context of microbiome research pertains to understanding the relationships between alterations in the microbiome and the onset, progression or exacerbation of diseases. It involves determining whether changes in the microbiome composition precede the development of a disease or occur as a consequence of the disease process or treatment, or are independent factors that also contribute to disease pathogenesis. This distinction is crucial, as it helps unravel the complex interplay between microbial communities and the health of their host. Additionally, establishing causality is essential for identifying molecular mechanisms underlying disease pathophysiology, which can serve as targets for therapeutic interventions. Furthermore, elucidating the causal role of the microbiome in disease aetiology is essential for the development and evaluation of microbiome-based therapies. By clarifying the causal relationships between microbiome alterations and disease outcomes, researchers can enhance their ability to design effective interventions that directly address the underlying mechanisms driving disease progression leading to improvement in disease outcomes.

Preclinical models that recapitulate host–microbiome interactions are often used to investigate the complex interplay between the gut microbiota and disease states and to enable the establishment of causality. These preclinical models encompass a spectrum of experimental systems, ranging from in vitro continuous culture systems and ex vivo organoids to sophisticated animal models, each offering distinct advantages and limitations for elucidating the contribution of the gut microbiota in health and disease20. In this context, in vitro continuous culture fermentation systems have emerged as a promising avenue to explore microorganism–microorganism interactions whilst minimizing animal testing21. They provide valuable insights into microbial physiology and interactions under controlled conditions and facilitate the study of microbial metabolism, community dynamics and response to environmental stimuli. These models also offer a high degree of reproducibility and enable researchers to manipulate individual microbial strains or communities to interrogate their effect on host physiology. For example, in vitro fermentation systems enable the cultivation of human-derived faecal samples under conditions that mimic the physiological conditions in different compartments of the gastrointestinal tract, thereby enabling translational, mechanism-focused investigations22. These models vary in complexity, from simple batch cultures suitable for short-term experiments to multistage systems that closely mimic different colonic regions23,24,25,26. However, they do not provide information about the host, its physiology and response to the microbiome. Nevertheless, although in vitro models such as SHIME27 are widely used in microbiome research, particularly as preclinical tools, in vitro models were excluded from this Delphi survey. The steering committee focused on models capable of addressing complex host–microbiome interactions and causality, which we believe are more comprehensively addressed by in vivo systems. However, the potential role of in vitro systems in specific contexts remains substantial and merits future exploration.

Ex vivo organoid cultures derived from primary tissue samples or pluripotent stem cells are an interesting platform for studying host–microbiome interactions in a controlled environment. Organoids recapitulate the cellular architecture and functionality of native tissues, enabling the ex vivo investigation of host–microbiome interactions at the cellular level of epithelial barrier function, as well as immune and metabolic responses28,29,30.The lack of peristalsis, and the absence of the full microenvironment, including immune, stromal and vascular components, point towards difficulties in the long-term culture of organoid systems. In parallel, organ-on-a-chip models have emerged as innovative tools for studying host–microbiome interactions with a higher degree of physiological relevance31. These microfluidic devices recreate microenvironmental conditions found in the human body, enabling the dynamic propagation of cells and tissues in a controlled manner. Organ-on-a-chip platforms offer the advantage of incorporating multiple cell types, including epithelial cells, immune cells and microbiota, within a microfluidic system that mimics the complex architecture and functions of organs such as the gut. This approach enables the real-time monitoring of cellular responses to microbial stimuli, barrier integrity and drug metabolism in a more physiologically relevant context. Nevertheless, and despite their advantages, the use of organoids and organ-on-a-chip models in studying host–microbiome interactions presents some limitations32,33,34. Challenges such as optimizing scaling, maintaining stable microbial communities, and replicating the complexity of human physiology persist. The simplicity of the current models, which often lack the intricate interactions of the gut microenvironment, can lead to results that might not fully translate to in vivo conditions. Additionally, technical limitations, high costs and the requirement for specialized equipment and expertise can hinder their widespread adoption. Thus, although these advanced culturing techniques represent a major step forward, they do not represent the full organ context, or even the organ–organ interactions in the human body without further refinement and validation. The use of organoids and organ-on-a-chip models is useful to complement the molecular and mechanistic insights from animal models and human interventions to gain a fully reliable understanding of host–microbiome interactions or to develop personalized therapies35.

In addition to in vitro models, animal models, including conventional and gnotobiotic mice have been instrumental in elucidating the causal relationships between gut microbiota dysbiosis and disease phenotypes. These models offer several advantages, including the availability of diverse inbred strains, and ease of genetic manipulation to mimic clinical phenotypes or underlying disease mechanisms. However, although animal models provide valuable insights, they do not entirely replicate the human gut microbiome and, therefore, their translational potential is rather limited in the context of human microbiota-associated (HMA) diseases18. To address this limitation, researchers have developed disease-relevant HMA mouse models by transferring faecal microbiota from healthy and diseased individuals into germ-free animals. Although these models have shown promise, they also come with their own set of limitations36. In addition to conventional and gnotobiotic mice, various animal models have been pivotal in investigating host–microbiome interactions. Caenorhabditis elegans offers genetic tractability and transparent anatomy for studying fundamental biological processes37. Drosophila melanogaster, with its simple gut microbial community, facilitates the dissection of host–microbiome interactions38. Zebrafish larvae, owing to their optical transparency and conserved innate immune system, enable real-time visualization of microbial colonization39. Pigs, which share physiological similarities with humans, offer insights into gastrointestinal health40, while non-human primates provide invaluable preclinical data due to their close resemblance to humans. The inclusion of diverse animal models in the Delphi survey underscores their complementary strengths and limitations, allowing a comprehensive understanding of host–microbiome interactions and the identification of therapeutic targets for microbiome-related diseases.

Delphi surveys offer a structured and iterative approach to gather insights from a panel of typically 30–50 leading experts, facilitating the synthesis of collective knowledge and the resolution of contentious issues41. They are particularly used in the field of medicine to overcome limitations associated with individual opinions through a transparent and reproducible framework with clearly defined criteria involving multiple rounds of anonymous feedback and consensus-seeking38, which promotes open dialogue and encourages participants to reconsider their viewpoints in light of collective feedback42,43. This iterative process allows refinement and clarification of key concepts and ensures that consensus emerges from a thorough and effective discussion34,35.

Here, we present insights from a Delphi survey conducted by the Human Microbiome Action Consortium, which examines the role of preclinical models in elucidating the link between the gut microbiome and diseases and identifying potential therapeutic interventions. Although this survey focuses primarily on gut microbiome research, it is essential to acknowledge that the microbiomes of other organs, such as those of the skin, lung and oral cavity, have crucial roles in health and disease. The exploration of microbiomes beyond the gut would indeed be an expansive area for future research, but for the purposes of this survey, we concentrated on the gut microbiome, given its established evidence base and therapeutic potential in a wide range of diseases. We highlight the latest progress in this field and discuss recommendations and consensus on the benefits and limitations of these models (Fig. 1). Specifically, we explore two key themes: establishing causality and validating microbiome-based therapies for clinical use. Additionally, we outline formal recommendations derived from the comprehensive Delphi survey aimed at improving both the understanding and application of microbiome science in clinical settings (Table 1). For example, to enhance evidence for diseases such as IBD, obesity, T2DM and liver diseases, we advocate for prioritizing longitudinal studies and expanding research into autism.

Summary of various microbiome model types alongside the outcomes of the Delphi survey. Model types include in vitro models, in vivo models, human microbiota-associated (HMA) models, and organoid and organ-on-a-chip models. The annotations provide insights into the strengths and limitations of each model type as identified through the Delphi survey. Note that, although in vitro models were intentionally excluded from the survey to focus on in vivo models, they are included in this summary for the sake of comprehensiveness.

We propose refining preclinical models through the use of HMA animals, standardizing protocols for organoids and organ-on-a-chip systems, and integrating multiple models to better replicate human conditions and ensure reproducibility. Additionally, we emphasize the need to document model strengths and limitations rigorously, promote microbiome modulation using dietary modifications and personalized therapies, and optimize therapeutic models by focusing on more relevant species such as pigs and non-human primates. Addressing interindividual variability through personalized approaches, implementing robust research strategies with standardized protocols and incorporating multiomics will enhance the depth of microbiome research. We also stress the importance of facilitating the transition from preclinical to clinical trials, patient stratification based on microbiome profiles and the standardization of experimental conditions to improve therapy development and effectiveness. Finally, investing in novel models and providing continuous training in advanced methodologies are critical for fostering innovation and elevating research quality. These recommendations are aimed at bridging the gap between experimental findings and clinical applications, ensuring that microbiome research translates into impactful and effective therapies.

Methods

Panel generation and statement development

The Delphi process started with the formation of a steering committee. The steering committee, comprising A.M., A. Kriaa, Z.H., F.C., C.D., A.F., H.M.B., E.M., and D.H., was responsible for conducting the literature review, setting up the Delphi survey stages, designing the questionnaires and analysing the responses. The expert panel, including P.W., J.W., S.R., M.S.D., K.A. and J.D., collaborated closely with the steering committee, discussing key scientific issues, contributing to the questionnaire design and identifying critical points for the manuscript based on the survey responses. The steering committee’s insights along with a literature review conducted on PubMed using specific keywords (“gut microbiome” AND “preclinical models” AND “causality”) informed the development of the Delphi questionnaire. The development of the Delphi questionnaire followed a comprehensive review of prior literature, consultation with experts and iterative refinement. The questionnaire “Preclinical models in microbiome research: How to prove causality & therapeutic inferences” consisted of two main sections: one addressing the role of preclinical models in establishing causality and the other focusing on therapeutic applications. The decision to exclude in vitro models from the Delphi survey was based on their current limitations in reflecting the complexity of host–microbiome interactions. Although certain systems are used in preclinical research, they often lack the ability to establish causality due to their simplified nature. The steering committee, therefore, decided to focus on in vivo models to address these complexities. Future iterations of this survey could consider incorporating in vitro systems to capture a broader spectrum of research tools. To ensure clarity and consistency among respondents, definitions of causality, therapeutic applications and predictive validity were provided. The questionnaire comprised 11 statements divided into two sections (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The statements were carefully reviewed and approved by the steering committee. Statements were designed to address critical aspects of microbiome research, including causality assessment, therapeutic applications, preclinical models and factors influencing interindividual variability. Each statement underwent thorough evaluation to ensure clarity and relevance.

Study settings and the Delphi protocol

The Delphi process was conducted online using the Clininfo platform, which adheres to the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to ensure the confidentiality and pseudoanonymity of the participants. The survey consisted of two rounds, conducted between May (round 1) and November (round 2) 2023. Each round utilized a six-point Likert scale for scoring, with the option “Not an expert/I don’t know” to account for varying levels of expertise on specific questions among the pluridisciplinary panel of participants (Supplementary Box 1). Respondents were encouraged to provide comments to clarify their answers. The comments were carefully reviewed and used to refine statements between rounds. Consensus was defined a priori (before survey launch) as achieving ≥66.7% agreement among respondents, with agreement encompassing both positive and negative perspectives on each statement. Statements that achieved consensus in the first round were excluded from the second round, whereas those that failed to reach consensus were refined based on feedback before being reconsidered in the subsequent round. Additionally, feedback from the steering committee was sought before launching the second round, and only experts who participated in the first round were invited to participate in the second round. Overall, the Delphi process aimed to systematically gather expert opinions, iteratively refining statements to reach consensus on the role of preclinical models in microbiome research, with a particular emphasis on establishing causality and validating the contribution of the microbiome to therapeutic implications in the context of various diseases. The complete survey results are shown in the supplementary material (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Participant engagement

The panel comprised 300 leading experts with experience in preclinical models, causality and the microbiome who were invited to participate in the Delphi survey. This panel was established through the steering committee’s professional network and by a comprehensive literature review on PubMed using the query key “gut microbiome” AND “preclinical models” AND “causality” to identify relevant studies over the past 5 years by authors, listed in either the first or last position, of at least ten relevant publications. Each expert received an individual Delphi ID to access the survey platform and complete the questionnaire. To maximize response rates, participants received weekly reminders from the platform supplemented by additional reminders sent regularly by a member of the steering committee. These efforts aimed to encourage active participation and ensure a representative sample of expert opinion.

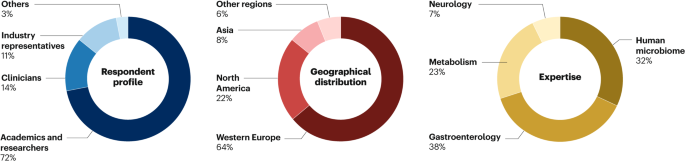

Respondent profile

In response to invitations sent to leading experts in the field of microbiome research, 107 experts participated in the first round of the Delphi survey. The second round was exclusively accessible to the same cohort of 107 respondents. Among the participants, the majority identified their professional backgrounds as academics and researchers (72.1%), followed by clinicians (14.4%) and industry representatives (10.5%). Regarding expertise areas, a substantial proportion were specialized in the human microbiome field (31.8%) and gastroenterology (38.4%), whereas smaller percentages focused on metabolism (23.3%) and neurology (6.5%). Respondents predominantly originated from Western Europe (64%). Notably, 39 female scientists participated in the survey (36.4% of respondents); gender was inferred based on participant name or other information. In round 2, 85 out of the initial 107 experts completed the survey (Fig. 2). According to the literature, responses from 30–50 respondents are considered sufficient44.

Distribution of respondent professional backgrounds, geographical locations and expertise areas in the Delphi survey. The majority of respondents identified as academics and researchers, followed by clinicians and industry representatives. Geographically, responses were predominantly from Western Europe. Expertise areas varied, with a major focus on the human microbiome and gastroenterology.

Findings and statements

The consensus process evaluated and led to agreement on a total of 11 key areas related to gut microbiome modulation, therapeutic interventions and preclinical models, alongside critical aspects of causality in microbiome research, indicating strong agreement among experts.

In terms of causality, the evidence strongly supported a causal role for the gut microbiome in IBD (92.93%), obesity (89.32%), T2DM (88.30%) and liver diseases (88.30%), although the evidence remained unclear for autism. Positive consensus was also achieved for using organoids and organ-on-a-chip systems in studying the causal role of gut microbiota (74.74% and 79.57%, respectively), especially when combined with animal models such as HMA animals (92.08%), genetically modified animals (87.13%) and chemically or nutrition-induced models (80.41%). The experts acknowledged limitations of these models, such as donor variability and lack of standardization, but emphasized the necessity of integrating additional experimental models to strengthen causality evidence (Supplementary Table 3).

On the therapeutic front, gut microbiome modulation was widely recognized as a promising approach for treating diseases such as IBD (92.63%), obesity (90.32%), T2DM (92.22%), liver diseases (91.86%) and autism (77.38%). Several interventions were identified as highly effective in modulating the microbiome; these included prebiotics (in IBD (77.42%), T2DM (69.66%) and liver diseases (68.35%)), synbiotics (in IBD (77.42%), T2DM (69.66%) and liver diseases (69.74%)), postbiotics (in IBD (75.56%), T2DM (70.24%) and liver diseases (67.57%)) and dietary interventions (in IBD (91.49%), obesity (97.96%), T2DM (94.68%) and liver diseases (85.71%)). However, no consensus was reached on the effectiveness of faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) (in IBD (86.46%), obesity (60%), T2DM (57.47%) and liver diseases (59.49%)) and probiotics (in IBD (69.89%), obesity (51.61%), T2DM (56.82%) and liver diseases (59.76%)), reflecting ongoing debate in these areas. Regarding preclinical models, a positive consensus was achieved for the suitability of porcine models (in IBD (74.67%), obesity (73.91%), T2DM (73.85%) and liver diseases (71.67%)) and non-human primates (in IBD (76.47%), obesity (78.46%), T2DM (77.78%) and liver diseases (74.58%)) in investigating therapeutic interventions across various diseases. Experts also reached a consensus on the major factors contributing to interindividual variability in human gut microbiomes, particularly lifestyle and/or environmental variability (in IBD (96.25%), obesity (98.8%), T2DM (98.78%) and liver diseases (98.63%)) and microbiome variability (in IBD (98.76%), obesity (96.34%), T2DM (95.06%) and liver diseases (95.83%)).

There was strong agreement on the need to standardize preclinical research methodologies, including: documenting relevant factors influencing the microbiome (88.24%), maintaining variability to reflect interindividual differences (89.02%), and ensuring appropriate reporting of animal model characteristics (99.01–100.00%). The consensus statements from both tables collectively provide a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the current state of gut microbiome research, its role in disease causality and its potential therapeutic applications (Supplementary Table 3).

Causality in microbiome research

In the first section of the Delphi survey, we aimed to evaluate the perception of the panel regarding the relevance of preclinical models in establishing causal links between alterations in the gut microbiota composition and various health conditions.

Causality between gut microbiome and various clinical conditions

To evaluate the level of evidence regarding causality in microbiome science, participants were asked to rate the strength of causality between the gut microbiome and various clinical conditions on a scale of one to six, with one representing “not at all established” and six indicating “fully established”. The consensus level for each disease varied. IBD achieved the highest consensus level, with 92.93% of respondents indicating clear evidence of causality (rated 4–6). Obesity achieved a positive consensus, with 89.32% of experts rating the evidence of causality as substantial (rated 4–6). T2DM and liver diseases also received favourable consensus levels, with 88.30% of respondents rating the evidence of causality as good (rated 4–6) for both conditions. Autism did not reach consensus, although 63.54% of experts acknowledged evidence of causality (rated 4–6), Notably, research on the causal relationship between the gut microbiome and autism is still relatively at its infancy compared with other diseases. Subsequent subgroup analysis focusing on neurology experts (comprising seven of the 107 respondents) revealed a negative consensus regarding the causal role of the gut microbiome in autism.

Methods to address causality

Among the preclinical models evaluated, animal models reached the highest percentages of agreement. HMA animals were endorsed by the majority of respondents, with 92.08% of respondents expressing a positive consensus. Genetically modified polygenic or gene knockout animals and chemically induced models also received favourable consensus levels at 87.13% and 80.41%, respectively. The culture-based preclinical models followed by organ-on-a-chip systems received the highest positive consensus at 79.57%, followed closely by organoids coupled with faecal inocula or individual-specific microbial isolates and/or microbial signatures at 74.74%. Then, cell lines coupled with faecal inocula or individual-specific microbial isolates and/or microbial consortia generated mixed responses, with 53.68% and 46.32% of respondents expressing positive or negative opinions, respectively. Notably, feedback from participants highlighted a general trust in complex cellular models for studying interactions and mechanisms, although concerns regarding the question of causality persisted. This concern prompted further investigation in the second round of the survey.

Limitations of organoids in establishing causality

Respondents who rated organoids as not relevant in establishing causality were asked about the main limitations of organoids in establishing causality, a positive consensus was reached for various factors. Notably, donor-to-donor variability in human organoids and lack of representativeness reached consensus, with 100% and 81.82% agreement, respectively. Other limitations reaching consensus included organ or tissue-specificity, possible readouts and lack of representativeness, indicating the multifaceted challenges associated with using organoids for studying causality, whereas limitations related to technical challenges (63.6% agreement) and cost (57.14% agreement) although highly cited did not reach the consensus level.

Limitations of organ-on-a-chip in establishing causality

For respondents who rated organ-on-a-chip models as not relevant in providing convincing evidence of causality, the main limitations of organ-on-a-chip in establishing causality were explored. There was a positive consensus regarding several limitations, with patient and/or donor variability and lack of representativeness being the most prominent concerns, with 94.12% and 100% agreement, respectively. Other limitations included organ and/or tissue-specificity, possible readouts, lack of standardization and cost, highlighting the multifaceted challenges associated with using organ-on-a-chip for studying causality. Notably, technical challenges although cited in a large percentage of replies (64.71%) did not reach consensus.

Evaluation of organoid and organ-on-a-chip models

In the second round, participants were asked to assess whether organoid and/or organ-on-a-chip models alone could provide convincing evidence of causality regarding the role of gut microbiota in health and disease. The responses indicated a lack of consensus, with 61.33% of experts expressing scepticism about the sufficiency of organoids and 62.16% for organ-on-a-chip models, whereas 38.66% and 37.83%, respectively, rated them as sufficient. Although both systems were deemed insufficient to draw strong conclusions about the causal role of gut microorganisms, they were acknowledged as valuable experimental models for testing specific hypotheses, suggesting the necessity of using a combination of methods to strengthen the evidence of causality, as confirmed by subsequent consensus. In response to whether additional experimental models should be used to support the evidence provided by organoid and/or organ-on-a-chip models, participants expressed a positive consensus, with 90% favouring the use of animal models and 95% advocating for human intervention studies, indicating the importance of complementary approaches to enhance the understanding of causality.

Human microbiota-associated animals in demonstrating causality

Parameters influencing demonstration of causality

Regarding HMA animals, experts were asked to identify parameters that would most influence the demonstration of causality. Positive consensus was observed for all parameters whereby the recipient animal, including germ-free animals, antibiotic-treated animals and specific pathogen-free (SPF) animals, emerged as the most influential parameter, with 97.09% agreement, followed closely by the efficiency of donor microbiota engraftment, with 96.04% agreement. Other influential parameters included interspecies distinctions between animals and humans (94.95%), microbial strain persistence over time (94.12%), number of donors (94.06%), housing conditions (93.27%), donor selection criteria (93.07%), handling and storage of donor stool material (90.1%), frequency of administration (86.14%) and delivery route of human donor stool material (83%). These consensual findings highlight the importance of carefully considering various parameters when using HMA animals in causality studies.

Limitations of rodent models in mimicking human disease

When assessing the capacity of rodents to replicate human disease, experts expressed a positive consensus (80.81% agreement) regarding the relatively limited capacity of HMA rodents to mimic human diseases. Whilst acknowledging rodents as valuable models for studying host–microbiome interactions, it was recognized that they possess inherent limitations in fully mimicking human pathophysiology. Despite this issue, rodents remain indispensable tools for hypothesis testing and preliminary investigations before advancing to more representative models or intervention studies. In the second round, the importance of rodent models in demonstrating causality for various clinical conditions was questioned again. A positive consensus was achieved for all selected diseases (ranging from 93.90% to 96.29% agreement, except autism (57.5% positive agreement), with most experts) endorsing the importance of rodent models in elucidating causal relationships between gut microbiota and disease.

Parameters limiting animal-to-human translation

In terms of factors impeding the translation of results from animal models to humans, experts reached positive consensus on the ten listed parameters (Supplementary Table 3, Statement 3C). Recipient animals and housing conditions emerged as particularly influential, with 95.88% agreement. This consensus underscores the critical importance of considering multiple factors when extrapolating findings from animal studies to the human context.

Proposals to improve relevance of preclinical models

Improving predictive validity of animal models

Only a minority of experts (40.74%) had proposals to enhancing predictive validity of animal models in their area of research in the first round, consensus was sought in the second round regarding the potential improvement by combining different models to mimic disease complexity. The majority (77.02%) agreed that such an approach could enhance the predictive validity of rodent models, suggesting a need for multifaceted modelling strategies to better mirror the complexities of human diseases.

Importance of documenting model

Full consensus (100%) was achieved regarding the necessity of documenting the strengths and limitations of available models to enhance result interpretation, emphasizing the critical role of transparent reporting in improving research rigor and reproducibility.

Feasibility and usefulness of preclinical model combinations

Most participants (ranging from 90.32% to 92.63% agreement for IBD, T2DM, liver diseases and obesity, and 77.38% for autism) deemed establishing a consensus on the most relevant combination of preclinical models both useful and feasible to elucidate causal host–microbiome interactions and their role in diseases.

Relevance of other animal models in demonstrating causality

For non-rodent models potentially relevant in demonstrating causality in IBD, T2DM, obesity and liver diseases, positive consensus (Statement 5; IBD (86.11%), obesity (85.51%), T2DM (85.71%) and liver diseases (83.33%)) was achieved for porcine and non-human primate models, deemed closer physiologically to humans. Conversely, negative consensus was noted for models such as C. elegans, Drosophila and zebrafish. Notably, regarding autism, non-human primates were the only models that obtained a consensus (72.55%), whereas other models reached a negative consensus (Supplementary Table 3). These findings underscore the importance of selecting appropriate model organisms tailored to specific research objectives.

Addressing therapeutic interventions in microbiome research

The second section of the Delphi survey focused on therapeutic interventions targeting the gut microbiome. Here, our objective was to assess the effectiveness of preclinical models in evaluating microbiome-based interventions and their potential therapeutic applications in various diseases. In this section, we provide a detailed overview of the statements and outcomes generated from the Delphi survey, offering valuable insights into the landscape of microbiome-based therapeutics.

Gut microbiome modulation as a therapeutic approach

A positive consensus was reached for the therapeutic potential of gut microbiome modulation in all diseases. This finding suggests optimism among experts regarding the efficacy of microbiome-targeting interventions in managing various diseases.

Promising interventions for microbiome modulation

For IBD, T2DM, obesity and liver diseases, the experts identified several interventions with promising potential for microbiome modulation. Although there was positive consensus for most interventions (notably dietary interventions, synthetic consortia, postbiotics, synbiotics and prebiotics) for IBD, T2DM and liver diseases, only dietary interventions and synthetic consortia achieved positive consensus for obesity, and none of the interventions reached consensus for autism. Notably, antibiotic interventions faced negative consensus in autism, T2DM and obesity, and negative agreement was very close to consensus for IBD (65.22%) and liver diseases (66.23%). Dietary interventions emerged as highly promising across all diseases.

Future modalities for microbiome therapeutics

Positive consensus was achieved for various microbiome-based modalities across diseases, although not in autism. ‘Bugs as drugs’ (78.26–93.62% depending on the condition) and ‘Drugs from bugs’ (81.32–90.43%) gained strong consensus, reflecting the growing interest in using live microorganisms and microbial-derived products for therapeutic purposes.

In the second round, a positive consensus was reached regarding the suitability of organoid and organ-on-a-chip models for testing therapeutic approaches (66.7% and 72.97%, respectively). This aspect highlights the potential of culture-based systems in evaluating the effects of gut microbiome-derived substances for therapeutic purposes, but the level of consensus also reflects the need for further developments and studies to enhance confidence in this approach.

Suitable preclinical models for therapeutic investigations

Beyond rodents, pigs and non-human primates received positive consensus as suitable models for investigating therapeutic interventions across four of the considered diseases (IBD, obesity, T2DM and liver diseases), emphasizing their physiological relevance to humans. Notably, rabbit, dog, Drosophila, C. elegans and zebrafish or killifish models reached negative consensus in all conditions. In addition, there was a negative consensus for all proposed models in autism except for non-human primates, which reached a positive agreement score of 62.5%, slightly below positive consensus.

Investigating interindividual variability

Animal models were generally considered unsuitable for studying interindividual variability in human gut microbiomes, except in T2DM. Factors contributing to interindividual variability in humans, including genetics, lifestyle and microbiome composition, were recognized as important across all diseases with positive consensus varying between 69% and 98.78% (Supplementary Table 3).

Discrepancy in the microbiomes of laboratory animal models

Experts largely agreed that the discrepancy in the microbiomes of laboratory animal models poses a major drawback in capturing the therapeutic effects of microbiome-based interventions (84.31%). This discrepancy makes it challenging to replicate results across different research settings.

Strategies to overcome lack of comparability

Standardization, documentation of relevant factors, and appropriate variability as well as appropriate documentation of analytical methods used were identified (positive consensus, ranging from 77.65% to 90.59%) as key strategies to overcome the lack of comparability and conflicting data in preclinical research, ensuring robustness and reproducibility of results.

Essential reporting for ensuring comparability

Several critical pieces of information were identified for reporting in preclinical models and/or experiments to ensure comparability, including animal characteristics, environmental data, treatment details and comprehensive microbiome characterization (98.04–100%) (Supplementary Table 3). This transparent reporting is essential for data reproducibility and interpretation.

Discussion

Understanding microbiome causality

The findings from the Delphi survey present important insights from experts in the microbiome field into their understanding of the current state of evidence related to the question of whether the microbiome causally contributes to the development of a range of diseases and the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions targeting the gut microbiome. One of the most important outcomes from the survey is the varying consensus levels among experts regarding the causal role of the gut microbiome in different clinical conditions. According to the Delphi survey, regarding a causal link between the gut microbiome and various clinical conditions, IBD achieved the highest consensus level, with 92.93% of respondents indicating clear evidence of causality. This finding aligns with the established literature highlighting the role of gut microbiota in IBD pathogenesis. Obesity also received a positive consensus, with 89.32% of experts rating the evidence of causality as substantial. Similarly, T2DM and liver diseases both received favourable consensus levels, with 88.30% of respondents rating the evidence of causality as good. By contrast, autism did not reach a consensus level, as only 63.54% of experts rated the evidence as supportive. However, caution is warranted when interpreting the findings related to autism, as the low number of neuroscientists among respondents might imply that the opinions gathered were less informed than those of experts in the fields of IBD and metabolic diseases. Furthermore, although emerging evidence suggests that alterations in the gut microbiota composition and function might be associated with ASD, including changes in microbial diversity, abundance of specific taxa and metabolic pathways, the causal relationship between gut dysbiosis and ASD remains unclear45,46. Some studies have found differences in the gut microbiome between individuals with ASD and neurotypical individuals as controls, suggesting a potential role of the gut–brain axis in ASD pathogenesis47,48. However, conflicting results and methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes49,50, heterogeneous study populations and variability in study methodologies, have led to controversy and uncertainty regarding the clinical significance of these findings20,50,51,52.

Models for studying microbiome causality

To further understand the methods for studying gut microbiota causality, HMA animals were strongly endorsed, with a positive consensus among 92.08% of respondents. Genetically modified polygenic or gene knockout animals and chemically induced models also received favourable consensus levels of 87.13% and 80.41%, respectively. Interestingly though, there was a positive consensus (80.81% agreement) regarding the limitations of rodent models in mimicking human disease. Despite these inherent limitations, the importance of rodent models in elucidating causal relationships between gut microbiota and various diseases remains crucial, as supported by the consensus on their relevance across numerous conditions (93.90% to 96.29% agreement), excluding autism, which achieved only 57.5% agreement. In vivo mouse models have a crucial role in preclinical research for studying disease mechanisms and testing potential treatments20. SPF animals, raised in controlled conditions and free from specific pathogens, provide a controlled environment for studying disease mechanisms and drug responses.

However, the immune systems of SPF animals are less developed due to their lack of exposure to a natural microbial environment, leading to less accurate predictions of human responses. To address this issue, researchers created ‘wildlings’ by transferring C57BL/6 embryos into wild mice, resulting in a colony with natural microbiota53. In contrast to SPF mice, wildling models, exposed to natural microbial environments from birth, display more mature immune systems and physiological responses akin to those in humans. Wildlings have shown superior predictive capabilities for human immune responses in various studies53,54. Despite these advantages, the increased microbial exposure and environmental complexity can introduce variability, complicating experimental reproducibility and data interpretation. Additionally, maintaining wildling colonies can be more labour-intensive and costly than maintaining SPF colonies. Moreover, numerous studies using gnotobiotic mouse experiments have established a causal link between gut microbiota and various diseases.

Germ-free mouse models offer a controlled environment for colonization with single bacterial strains, defined bacterial consortia or complex gut microbial ecosystems derived from human donors55,56,57,58. In addition, defined minimal bacterial consortia are considered sufficiently complex to support immune maturation yet allowing additional colonization by other specific bacterial strains59. Examples include the Schaedler Flora and Altered Schaedler Flora (ASF)60, designed to control bacterial presence whilst increasing complexity, and the Oligo-Mouse Microbiota 12 (ref. 58), noted for its stability, reproducibility and ability to enhance immune maturation compared with ASF58,61. Other consortia, such as one by Tanoue et al. comprising 11 human commensal strains, have demonstrated stimulation of IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells, enhancing resistance to pathogens and supporting antitumour activity62. Similarly, the GM15 consortium, derived from SPF mice, has facilitated the creation of gnotobiotic mice closely mimicking SPF mice in immune responses63. The SM14, a functionally characterized, 14-member synthetic human microbiota has been developed and used to investigate bacteria and functions responsible for pathogen susceptibility64.

Colonization of germ-free mice with human faecal microbiota, known as HMA mice, have been extensively used to investigate the pathogenic mechanisms of complex diseases, including IBD65,66,67, T2DM, obesity15,68, asthma69, malnutrition70 and colorectal cancer71,72,73. However, standardizing microbiota transfer poses challenges, leading to variability in microbial composition among mice and potentially affecting reproducibility. Selective colonization of germ-free mice with defined complex human bacterial communities (hCom) is one possible way to overcome the latter limitations74. Fischbach and colleagues developed humanized mice colonized with a consortium of 119 species74. Encouragingly, readouts of immune markers of hCom gnotobiotic mice revealed similar levels of immunocompetence compared with SPF housed mice75. Achieving consistent colonization efficiency of human FMT into germ-free recipient mice remains an obstacle being influenced by various factors such as diet, housing conditions and donor material sampling, again arguing for the design of synthetic hCom with individual strain variations. Nevertheless, the individual variation of human microbiota clearly limits a full coverage of human diversity, supporting the concept of applying defined hCom20,36,76. In exploring the role of HMA animals, experts reached a positive consensus on several parameters influencing causality demonstration, with recipient animals, including germ-free and antibiotic-treated animals, highlighted as pivotal. Notably, parameters such as donor microbiota engraftment efficiency (96.04% agreement) and interspecies distinctions (94.95% agreement) were underscored. This consensus emphasizes the critical considerations necessary for using these models effectively. Proposals for improving predictive validity in animal models were discussed, with 77.02% of experts agreeing that combining different models could enhance predictive validity, thereby indicating a need for multifaceted modelling strategies. Furthermore, the necessity for documenting model strengths and limitations achieved full consensus (100%), emphasizing the importance of transparency in research to improve rigour and reproducibility.

Advances in preclinical models

When considering suitable preclinical models for research, the survey results underscore the importance of selecting models that closely mimic human physiology. Although rodents remain essential in preclinical research, pigs and non-human primates garnered positive consensus for their relevance in studying therapeutic interventions. By contrast, traditional models such as rabbits, dogs and invertebrates did not achieve consensus across any conditions, emphasizing their limitations in capturing the complexities of human gut microbiome interactions. Pigs are a compelling choice for elucidating the underlying mechanisms contributing to complications in patients with insulin-resistant T2DM due to their similarities to humans in pharmacokinetics following subcutaneous drug administration, gastrointestinal structure and function, pancreas morphology and overall metabolic status55. Additionally, pigs have proven valuable in studying cardiovascular, renal and ophthalmic complications associated with streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes mellitus56,57,58,77. Notably, their use in testing medications (such as statins) and devices (such as stents) has shown high predictive value for human translation. Given the accelerated disease progression in patients with diabetes mellitus, pigs offer a promising model for exploring the mechanisms behind diabetic complications and evaluating new therapies in insulin-resistant T2DM58,67,68,78,79,80,81. Moreover, both pig and human bacterial culture collections are available to investigate the effect of specific bacterial strains (such as in IBD)82. Pigs can be fed a human diet, and faecal microbiota transfer from humans to pigs results in a gut microbiota closely resembling that of the human donor83. For instance, TNFΔARE pigs are a promising model for Crohn’s disease, resembling the disease manifestation observed in humans40. Pigs can also be raised under germ-free conditions and transferring microbiomes from humans to pigs leads to the development of a gut microbiota closely resembling that of the human donor72. This similarity enables the evaluation of novel diagnostic technologies on a human scale84.

Addressing interindividual variability

However, the interindividual variability in human gut microbiomes is another critical aspect highlighted by the survey. Although animal models were generally deemed unsuitable for studying this variability, the recognition of genetics, lifestyle and microbiome composition as major factors emphasizes the complexity of microbiome interactions in human health. One approach to investigate these interactions, as previously suggested, is the implementation of different human microbiota in transfer experiments. Yet, despite their utility, these experiments face inherent limitations, particularly the habitat differences between humans and model organisms. Furthermore, transfer experiments do not account for critical human-specific factors, such as individual genetic risk and environmental exposure, which are essential to understanding how microbiomes influence health36,76. Addressing this variability is crucial for developing effective microbiome-based therapies. A noteworthy concern identified by experts is the discrepancy in the microbiome of laboratory animal models, which poses a major challenge in replicating the therapeutic effects of interventions across different research settings. Strategies to overcome these limitations include standardization, comprehensive documentation of relevant factors and transparent reporting of analytical methods. The emphasis on essential reporting elements — such as animal characteristics, environmental data, treatment details and microbiome characterization — will enhance the reproducibility and interpretation of preclinical findings, ultimately advancing the field of microbiome research.

Emerging in vitro models

The survey results also underscore notable limitations in the use of organoids and organ-on-a-chip models for establishing causality. Organoids, derived from stem cells, provide a 3D structure that mimics specific organs, providing a physiologically relevant platform for studying human biology and disease28,85,86. They offer several advantages, including the ability to recapitulate complex tissue structures and cellular interactions in vitro, enabling the study of disease mechanisms and drug responses in a more accurate and controlled environment87. However, a major drawback is their lack of integration with other organ systems and physiological processes, limiting their ability to model systemic diseases and interactions between different tissues. Organoids are also heterogeneous in terms of size, shape and cell composition, which can introduce variability and complicate data interpretation. Furthermore, organoids might not fully replicate the complexity of in vivo microenvironments, such as immune cell interactions and blood flow, which are critical for disease progression and drug responses. These limitations were reflected in the survey results in which organoids proved to face challenges such as donor-to-donor variability and lack of standardization, with 100% and 81.82% agreement among experts, respectively. By contrast, gut-on-a-chip models utilize a microfluidic platform to simulate the human intestine’s structural and functional features, enabling the study of complex cell–cell interactions and physiological processes in a controlled environment88.

Despite these advantages, survey respondents highlighted criticisms regarding patient/donor variability and lack of representativeness in gut-on-a-chip models, which received 94.12% and 100% agreement, respectively. Notably, gut-on-a-chip systems can be integrated with other organ-on-a-chip models. For instance, the HuMiX gut-on-a-chip has been combined with a liver-on-a-chip model (Dynamic42) to study the enterohepatic recirculation and biotransformation of irinotecan, an anticancer drug89. This multiorgan-on-a-chip platform mimics the gut–liver axis, in which the human microbiome markedly influences drug metabolism. It supports the viability and functionality of both intestinal and liver cells, enhancing understanding of microbiome-driven effects on drug metabolism. In a proof-of-concept study, researchers used liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry to track irinotecan metabolites, confirming the capability of the platform to represent drug metabolism along the gut–liver axis. The study revealed that the colorectal cancer-associated bacterium Escherichia coli alters irinotecan metabolism by converting its inactive metabolite SN-38G into the toxic metabolite SN-38. This finding highlights the potential of this platform for exploring the interactions between gut microorganisms and pharmaceuticals, offering a valuable alternative to animal models and novel drug development strategies. However, a limitation of gut-on-a-chip models is their complexity and technical challenges associated with fabrication and operation, requiring specialized equipment and expertise for their development and use90.

In evaluating the efficacy of these models, the survey revealed a lack of consensus on whether organoid and organ-on-a-chip models alone could provide convincing evidence of causality. Scepticism was noted, with 61.33% of experts expressing doubts about organoids and 62.16% expressing doubts about organ-on-a-chip models being sufficient. Despite these reservations, both systems were acknowledged as valuable experimental models for testing specific hypotheses, further emphasizing the necessity for employing a combination of methods to strengthen causal evidence.

Future directions and recommendations

The findings from the Delphi survey provide substantial insights into the therapeutic interventions targeting the gut microbiome, and highlight the consensus among experts in the field. A key takeaway is the optimistic view regarding the therapeutic potential of gut microbiome modulation across various diseases, underscoring the growing recognition of microbiome-targeting interventions as viable strategies for managing conditions such as IBD, T2DM and obesity. Experts identified a range of promising interventions, including dietary modifications, synthetic consortia, postbiotics, synbiotics and prebiotics, particularly for IBD, T2DM and liver diseases. Dietary interventions, in particular, emerged as a highly favoured approach among respondents across all conditions evaluated, indicating their relevance in therapeutic strategies. Conversely, the lack of consensus on interventions for autism points to the need for further research to explore the complexities of the role of the microbiome in neurodevelopmental disorders. Notably, antibiotics received a negative consensus in the context of autism, T2DM and obesity, suggesting caution in their use and the need for alternative therapeutic approaches in these areas. Another key theme that emerged from the survey is the general consensus that lifestyle and diet play a major part in shaping the human gut microbiome, with dietary interventions being the most widely agreed-upon therapeutic modulator. However, this brings to light certain challenges in microbiome research, particularly when using animal models. Although animal models are valuable for investigating mechanistic links, they often fall short in replicating the complexity of human lifestyle and dietary patterns. This limitation raises important questions about how effectively animal models can be used to translate findings into therapeutic strategies for human populations, and highlights the need for complementary approaches, such as controlled human trials or advanced in vitro systems, to better simulate these factors.

The survey findings also revealed a strong interest in novel therapeutic modalities, specifically the concepts of ‘bugs as drugs’ and ‘drugs from bugs’. The substantial consensus on these modalities reflects a paradigm shift towards utilizing live microorganisms and microbial-derived products in therapeutic applications. The Delphi process additionally identified issues with standardization, reproducibility and comparability in preclinical studies. To address these challenges, standardized protocols, improved reporting guidelines, increased collaboration and data sharing are needed within the scientific community. Integrating multiomics approaches such as metagenomics and metabolomics shows potential for understanding microbiome-mediated mechanisms and therapeutic responses. Personalized medicine based on individual microbiome profiles could revolutionize disease management and treatment strategies, offering promising possibilities for the future. Furthermore, and despite identifying microbiome signatures in various contexts such as disease pathogenesis91 and treatment response, qualified microbiome-based biomarkers are not yet used in clinical practice. In this context, The Human Microbiome Action Consortium conducted another Delphi survey to establish a consensus on the challenges and limitations in developing such biomarkers92. The survey, which involved 307 experts, revealed confidence in the potential of microbiome-based biomarkers across several indications. However, the lack of validated analytical methods was identified as the primary barrier to their qualification. The survey emphasized that clinical implementation would require the development of validated, easy-to-use molecular assays.

In conclusion, the Delphi survey underscores the therapeutic potential of gut microbiome modulation whilst highlighting the need for rigorous methodologies and appropriate model selection in microbiome research. The consensus on promising interventions and future modalities reflects the optimism surrounding microbiome-targeted therapies, paving the way for innovative approaches in managing various diseases. Continued collaboration among researchers, clinicians and industry stakeholders is essential to address the challenges identified and fully leverage the therapeutic opportunities presented by the gut microbiome. The recommendations derived from the Delphi survey findings are detailed in Table 1. These provide actionable insights into advancing microbiome research and clinical applications, highlighting the collective expertise and priorities of the contributors.

Strengths and limitations

The Delphi method used in this study, although robust for achieving expert consensus, has strengths and limitations that need to be acknowledged. Our process began with the formation of a steering committee, composed of the listed authors, who were selected based on their extensive expertise and contributions to the field of microbiome research. This committee was responsible for reviewing commonly used preclinical models and their relevance in studying causal relationships and host–microbiome interactions in areas such as IBD, T2DM, obesity, liver diseases and autism. Their insights, combined with a thorough literature review, informed the development of the Delphi questionnaire.

One of the key strengths of our Delphi process was the use of a diverse expert panel. We initially used purposive sampling to form the core group and then expanded the panel through snowball sampling, leveraging the professional networks of the core group members. This approach helped mitigate the bias associated with purposive sampling and resulted in a panel of 300 leading experts from various disciplines and geographical regions. The inclusion of experts from academia, clinical practice, industry and research ensured a comprehensive range of perspectives, thereby enhancing the validity of the consensus statements. Additionally, the iterative refinement of the Delphi questionnaire, which covered critical areas such as causality and therapeutic applications in microbiome research, enabled precise adjustments based on expert feedback. This iterative approach helped enhance the relevance and clarity of the 11 statements presented to the panel. The adherence of the Clininfo platform to GDPR regulations ensured participant confidentiality and pseudoanonymity, which is likely to have encouraged honest and unbiased responses from the diverse panel of 107 experts. The incorporation of both qualitative comments and quantitative ratings in the survey provided a comprehensive view of expert opinions, ensuring that the final consensus reflected a well-rounded perspective on the role of preclinical models.

However, there were specific limitations to the process. One limitation relates to the composition of the expert panel, which, despite efforts to ensure diversity, had a higher representation of gastroenterology experts (38.4%) compared with other fields such as neurology (6.5%). This imbalance might have influenced the levels of consensus achieved, particularly favouring gastrointestinal diseases over other conditions. As such, results should be interpreted with caution, especially when considering diseases with fewer experts represented. We acknowledge that the predominance of experts from specific fields, such as gastroenterology, might have skewed the results and potentially influenced the strength of consensus on certain topics. Additionally, the initial selection of the steering committee, although designed to include leading experts, might have introduced bias. The recommendations of this core group influenced the composition of the broader expert panel, potentially skewing the diversity of perspectives. Although the use of snowball sampling aimed to broaden the panel, the potential for selection bias remained. Additionally, the geographical distribution of respondents was unbalanced, with 64% of experts coming from Western Europe, which does not reflect the global landscape of microbiome research and publications. Although we made efforts to contact experts from under-represented regions such as Africa, Asia and Latin America, the response rate from these areas was low. Furthermore, a gender bias was evident, with the majority of respondents identified as men (Supplementary Table 2). This imbalance might have influenced the perspectives represented in the survey. Lastly, although we included a breakdown of experts by primary field, we did not collect information on career stage. Such data could have provided valuable additional insights into the demographics of the panel and highlighted potential disparities in representation across career stages. We recommend addressing this limitation in future surveys to enhance the diversity of perspectives and ensure a more comprehensive analysis.

This regional concentration might have introduced a bias towards European research priorities and perspectives. Future studies should aim for broader outreach and improved engagement in these regions to ensure a more globally representative panel. Another important limitation is related to regional policy influences, particularly within the EU, which is actively promoting in vitro and ex vitro models as alternatives to traditional animal models. This policy shift could have shaped the preferences of EU-based experts who comprised a substantial proportion of our panel (64% Western European), potentially introducing a regional bias into the survey outcomes. In future surveys, it will be essential to consider these regulatory developments explicitly and analyse how they might influence expert consensus on preclinical models across different regions. The online format of the survey, a necessity due to geographical and logistical constraints, precluded real-time, face-to-face discussions, which could have facilitated deeper exploration of complex issues and improved consensus on contentious topics. Moreover, the survey was conducted solely in English, which might have excluded non-English-speaking experts and affected the inclusivity of the panel. Finally, the threshold for consensus set at ≥66.7% might not have fully captured the depth of expert disagreement on more nuanced issues, potentially oversimplifying complex debates. Notably, in vitro models, which are commonly used in microbiome research as preclinical tools, were excluded from this Delphi survey. While this aspect was outside the scope of the current study, a similar consensus-building process focusing on in vitro models could offer valuable complementary insights, further contributing to the methodological framework for microbiome research. These strengths and limitations highlight the effectiveness of the Delphi method in reaching a consensus on preclinical models and microbiome research, whilst also pointing to areas in which future studies could enhance the process by addressing biases, incorporating real-time discussions and ensuring broader linguistic accessibility.

Conclusions

Overall, this Delphi survey provided valuable insights into the current state of microbiome research and highlighted opportunities for advances in research and areas requiring further investigation (Fig. 1). Based on the outcomes of the Delphi survey, we propose the recommendations presented in Table 1 to advance our understanding of the microbiome and enhance its translation into clinical practice.

Responses