A critical role of N4-acetylation of cytidine in mRNA by NAT10 in T cell expansion and antiviral immunity

Main

As a key component of the immune system, naive T (TN) cells undergo rapid clonal expansion and differentiation following antigen stimulation to execute an efficient immune response. During this process, T cells reprogram the proteome and substantially augment protein synthesis to fulfill robust bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands. A study of the ribosomal translation dynamics of T cells showed that in the initial phases of T cell activation (6 h after T cell antigen receptor (TCR) stimulation), protein synthesis can increase to as much as five times that of the resting state, whereas cellular RNA content increases by only 1.37 times, indicating the core role of post-transcriptional regulation at this stage1.

Unraveling the mechanisms underpinning cell expansion is pivotal for understanding the regulation of immune responses and gaining insights into immune dysfunction.

Currently, over 170 ribonucleotide modifications have been identified, with new types continually emerging. Following RNA synthesis, a wide variety of molecular changes could be implemented by highly conserved enzyme systems under physiological or pathological circumstances. N4-Acetylcytidine (ac4C) is currently the only acetylation mark observed in RNA. In 2018, Arango et al. reported the ‘writer’ protein for ac4C, N‐acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10), as well as the biological function of ac4C in maintaining mRNA stability and promoting translation efficacy. The potential role of NAT10-mediated ac4C modification in several diseases and conditions, such as premature aging, autoimmune diseases, infection, inflammation and cancer, has been reported2,3,4,5,6.

Recent studies have revealed the epitranscriptomic mechanisms in T cell homeostasis adaptation. N6-Methyladenosine modification of mRNAs can promote T cell proliferation and differentiation via accelerating the degradation of suppressors of cytokine signaling family genes, which encode major physiological inhibitors of JAK–STAT signaling pathways7. Epitranscriptomic regulation of T cell functionality has increasingly become a research hot spot, but the physiological role of ac4C in mammalian T cells is still unknown.

Here, we investigated how ac4C controls T cell homeostasis via conditional knockout (CKO) of Nat10. Our data indicated that loss of NAT10 significantly diminished ac4C marks on mRNAs, which in turn changed the entire transcriptional profile of T cells. As a result, CKO mice showed significant defective T cell expansion, which aggravated infection in a mouse lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) model. From a mechanistic standpoint, the installation of mRNA-ac4C by NAT10 on early upregulated mRNAs contributed to the translation of key proteins essential for T cell proliferation, notably MYC. MYC, in turn, propeled T cells into mitosis, enabling them to complete the cell cycle. Notably, the NAT10–MYC axis displayed a certain level of impairment in T cells derived from older individuals, which may partially account for age-related antiviral defects in this population. Together, these findings highlight the role of mRNA-ac4C modification as a translational checkpoint of T cell expansion mainly via facilitating MYC protein synthesis.

Results

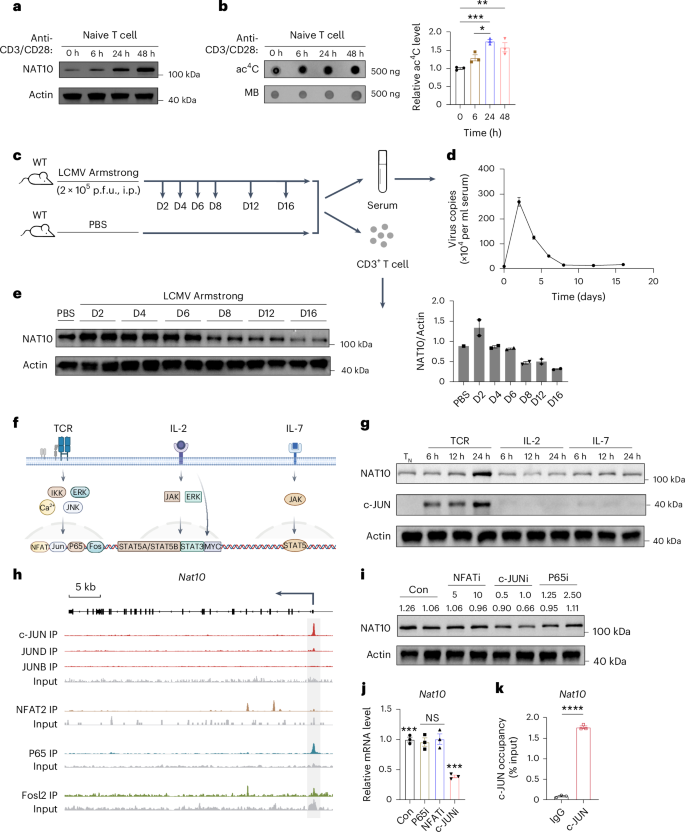

NAT10 is upregulated during T cell activation

To investigate the potential role of NAT10 in T cell functionality, we first analyzed the dynamic changes in NAT10 expression in T cells undergoing TCR-based activation. We found that, compared to the low expression of NAT10 in mouse splenic TN cells, cells treated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 6, 24 and 48 h showed dramatic increases in NAT10 protein expression (Fig. 1a). Consistently, dot blots demonstrated enhanced ac4C abundance on total RNA isolated from activated T cells, with methylene blue staining as a loading control (Fig. 1b). Next, to determine whether NAT10 is also involved in T cell activation in vivo, we developed an acute infection mouse model using LCMV (Fig. 1c). Wild-type (WT) mice were intraperitoneally infected with 2 × 105 plaque-forming units (p.f.u.) of LCMV Armstrong and killed at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 16 days after infection8. Serum was collected for RNA extraction, and CD3+ T cells were isolated for western blotting. LCMV titers measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) showed that LCMV replicated rapidly at early stages of infection, and this was essentially eliminated at day 8 (Fig. 1d). The dynamic changes in NAT10 protein expression were aligned to viral load, suggesting that, similar to in vitro T cell activation (Fig. 1a), NAT10 in T cells also responds to activation and viral clearance in vivo (Fig. 1e).

a, NAT10 expression in CD3+ TN cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for the indicated lengths of time. b, Dot blot and densitometry analysis of ac4C modifications in total RNA (500 ng) of CD3+ TN cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for the indicated lengths of time. Left, representative anti-ac4C dot blot. Right, bar graph showing the relative ac4C intensities normalized to total RNA quantified by methylene blue; n = 3; *P = 0.0153, **P = 0.0039 and ***P = 0.0007. c, Schematic of the acute LCMV infection model in WT mice. Eight-week-old WT mice were intraperitoneally injected with 2 × 105 p.f.u. LCMV (Armstrong strain) and killed at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 16 days after infection. Mice treated with equal volumes of PBS served as controls. Serum RNA and CD3+ T cells were isolated for further analysis; D, day; i.p., intraperitoneal. d, Changes in serum viral load during infection; n = 3. e, Western blot and densitometry analysis of NAT10 protein expression in T cells of LCMV Armstrong-infected mice at the indicated times. Each blot represents an independent biological sample. f, Schematic diagram of TCR, IL-2 and IL-7 signaling pathways during T cell activation. Image created using BioRender. g, NAT10 and c-JUN expression in CD3+ TN cells stimulated with TCR (anti-CD3/CD28), IL-2 and IL-7 for the indicated lengths of time. h, IGV snapshots showing c-JUN, JUND, JUNB, NFAT2, P65 and FOSL2 binding sites at the Nat10 locus. The arrow indicates the start site and transcription direction. i, NAT10 expression in CD3+ TN cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 h in the presence of NFAT inhibitor (NFATi), c-JUN inhibitor (c-JUNi), P65 inhibitor (P65i) and an equal volume of DMSO at the indicated concentrations (in μM), respectively. j, Nat10 expression at the transcriptional level under the same conditions as in i; n = 3. The following are the exact P values from left to right: ***P = 0.0004, ***P = 0.0007, ***P = 0.0004 and not significant (NS), P > 0.05; Con, control. k, c-JUN ChIP–qPCR for the Nat10 locus in CD3+ TN cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 h; n = 3; ****P < 0.0001. n refers to the number of biologically independent samples. Error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. (b, d, e, j and k). Representative data of three independent experiments are presented (a, b, d, e, g and i). Data were analyzed by two-tailed, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (b and j) and two-tailed, unpaired t-test (k).

Source data

We then sought to determine the potential upstream signaling responsible for NAT10 upregulation during T cell activation. As TCR, interleukin-2 (IL-2) and IL-7 signaling serve as the major pathways at the early stage of T cell activation, we stimulated TN cells with TCR (anti-CD3/CD28), IL-2 and IL-7 for the indicated lengths of time, respectively (Fig. 1f,g). Given NAT10’s specific response to anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation, it might be downstream of TCR signaling (Fig. 1g). We then reanalyzed the published activated T cell chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing (ChIP–seq) data to explore the probable binding sites of the major transcription factors within TCR pathways (Fig. 1h)9,10,11,12. c-JUN, NFAT2 and P65 were found bound within the Nat10 body or 2 kb upstream, suggesting their potential roles in regulating Nat10 transcription (Fig. 1h). We then stimulated TN cells with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 h, together with inhibitors of these transcription factors, and found that only the c-JUN inhibitor led to decreased NAT10 expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1i). Consistently, qPCR analysis under the same condition showed a significant drop in Nat10 transcript levels following c-JUN inhibition (Fig. 1j). Furthermore, western blot analysis revealed an upward trend in c-JUN expression during T cell activation, similar to but before that of NAT10 (Fig. 1g). Finally, the binding of c-JUN to the Nat10 locus was confirmed by ChIP–qPCR experiments (Fig. 1k). Together, these data suggest that TCR signaling activates NAT10-mediated ac4C processing during T cell activation via c-JUN.

NAT10 helps to maintain the pool of T cells

To further explore the specific role of NAT10 in T cells, we generated Nat10 T cell-CKO (Nat10fl/flCd4Cre; hereafter CKO) mice using a Cre/loxP recombination system. CKO T cells exhibited diminished NAT10 expression and ac4C levels compared to those from Nat10fl/fl (hereafter FLOX) mice (Fig. 2a,b). Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) was then conducted on thymic and splenic cells from 6- to 8-week-old FLOX and CKO mice to depict NAT10’s role in T cell development and differentiation. In total, eight cell types, including 28 clusters, were revealed via unsupervised hierarchical clustering and visualized by t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE; Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 1a). The scRNA-seq data showed that T cells were significantly reduced in the spleen but not in the thymus, indicating that CKO of Nat10 mainly perturbed splenic rather than thymic T cell development (Fig. 2d,e and Extended Data Fig. 1b). Next, we extracted splenic T cells for deeper uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) dimension reduction analysis. A total of eight T cell clusters were presented according to known marker genes, and all these populations were decreased in CKO mice (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d). Consistent with the scRNA-seq data, flow cytometry (FCM) analysis also confirmed dramatic shrinkage of the CKO T cell pool (Fig. 2f–i). These changes were extensive in not only immune organs but also other parenchymal organs, such as the lung and kidney (Fig. 2j). However, no changes were detected between FLOX and CKO T cells of the thymus in the double-negative, double-positive and mature single-positive stages, respectively (Fig. 2k), indicating that the early developmental stages of T cells in the thymus are unaffected. In addition to cell proportions, differentially expressed genes were also analyzed. Compared to controls (blue block), the top eight upregulated (Gh, Ttn, Smu1, Top2a, Igfbp4,Tnfsf8, Cd7 and Bcl2) and top ten downregulated (Rps7, Rps28, Rps24, Rps9, Rps16, Icos, Rps28, Rpl12, Cd8a and Cd8b1) genes in CKO T cells were assessed (Extended Data Fig. 1e). We found that genes encoding ribosomal proteins were dramatically decreased in expression following NAT10 deficiency, which is consistent with earlier reports13,14,15. Notably, the critical T cell markers CD8a and CD8b1 were also considerably downregulated in CD8+ CKO T cells at both the mRNA and protein levels, which partially accounts for the contraction of CD3+, especially CD8+, T cells (Extended Data Fig. 1f).

a, NAT10 protein expression in CD3+ TN cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for the indicated lengths of time (top) or CD4+ and CD8+ TN cells stimulated for 24 h from FLOX and CKO mice (bottom). b, Dot blot and densitometry analysis of ac4C modifications in total RNA (1,000 ng) from CD4+ and CD8+ TN cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 h. Left, representative anti-ac4C dot blot. Right, bar graph showing the relative ac4C intensities quantified by methylene blue; n = 3; **P = 0.0037 and *P = 0.0103. c, Comprehensive t-SNE visualization of splenic and thymic single cells from 6- to 8-week-old FLOX and CKO mice by cell type; NK, natural killer. d, Separate displays of c by different group, with the same color coding. e, Bar plot showing the percentages of each cluster across groups; related to d; S, splenic; T, thymic. f, Representative FCM plots of splenic CD3+TCRβ+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in 8-week-old FLOX and CKO mice in vivo. g, Percentage of CD3+TCRβ+ T cells and absolute numbers of CD3+TCRβ+, CD4+, CD8+ and double-negative (DN) T cells in the spleens of FLOX and CKO mice; n = 3; ****P < 0.0001, ***({P}_{{rm{No.}}, {rm{CD}}3^{+}{rm{TCR}}upbeta^{+}}) = 0.0010, ***(P_{rm{No}. rm{CD8}^+}) = 0.0003, ***PNo. DN = 0.0008 and **P = 0.0031. h, Representative FCM plots of CD3+TCRβ+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in inguinal lymph nodes of FLOX and CKO mice. i, Percentage of CD3+TCRβ+ T cells and absolute number of CD3+TCRβ+, CD4+, CD8+ and double-negative T cells in inguinal lymph nodes of FLOX and CKO mice; n = 3; ****P < 0.0001, ***P = 0.0001, **P = 0.0022 and *P = 0.0183. j, Proportions of CD3+TCRβ+ T cells in spleen, lymph node, lung, kidney and liver of FLOX and CKO mice; n = 3. ****P < 0.0001, **PLymph node = 0.0081, **PLung = 0.0022 and *P = 0.0104; NS (not significant), P > 0.05. k, Thymic double-negative, double-positive (DP) and CD4+ and CD8+ single-positive (SP) T cells in FLOX and CKO mice. Left, representative FCM plots. Right, bar graphs showing proportions and absolute numbers of indicated thymic populations in FLOX and CKO mice; n = 3. n refers to the number of biologically independent samples. Error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. (b, g and i–k). Representative data of three independent experiments are presented (a). Data were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired t-test (b, g and i–k).

Source data

Functionally, CKO T cells were more hyperactive than FLOX control T cells. The fraction of TN cells decreased, whereas the effector T (TEFF) cell proportion increased in CKO T cells in the resting state (Extended Data Fig. 2a). CD69 and CD44, T cell early activation markers, were more highly expressed in CKO T cells following TCR stimulation (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Additionally, without stimulation, CKO CD8+ T cells synthesized more effector molecules under quiescent conditions, such as interferon-γ (IFNγ), granzyme A (GZMA), granzyme B (GZMB), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and perforin (Extended Data Fig. 2c–g). However, the reason why T cells are hyperactive following NAT10 deficiency remains largely unknown. Lymphopenia-induced spontaneous proliferation may be involved in this phenotypic shift16. Dysregulation of key molecules that maintain cellular homeostasis may also contribute. The specific mechanism remains to be discovered.

Loss of NAT10 causes impaired T cell proliferation and enhanced apoptosis

To determine why CKO T cells significantly decreased in number, we performed a series of proliferation experiments. First, TN cells from CD45.1+ FLOX and CD45.2+ CKO mice were isolated for in vivo proliferation assays. Cells from the two groups were labeled using CellTrace, mixed at a 1:1 ratio and transferred into Rag2−/− mice. Ninety-six hours later, proportion and CellTrace dilution analyses were performed via FCM (Fig. 3a). We observed that recipients contained significantly lower percentages of donor T cells from CKO mice than from FLOX controls (Fig. 3b). Consistently, T cells presented a remarkable proliferative defect following Nat10 deletion (Fig. 3b). TN cells from CKO mice that were labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) in vitro also showed impaired expansion potential (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, CKO T cells failed to increase in size, as determined by the smaller granularity detected via FCM, suggesting NAT10’s critical role in regulating cell growth (Fig. 3c). We next performed cell cycle analysis to determine which stage the CKO T cells were arrested in. BrdU/7-AAD double staining showed that the fraction of cells that entered into S phase significantly decreased, with more arrested in the G0–G1 phase in CKO T cells (Fig. 3d). Another factor influencing T cell population size was the rate of apoptosis. We found that both early and late apoptosis of splenic T cells was increased in CKO mice compared to in FLOX mice, as was also the case in T cells from the lymph node (Fig. 3e,f). Together, these abnormalities in proliferation and apoptosis contribute to dramatic shrinkage of the CKO T cell pool.

a, Schematic showing the in vivo competitive proliferation assays. TN cells isolated from 8-week-old CD45.1+ FLOX and CD45.2+ CKO mice were labeled with CellTrace, mixed at a 1:1 ratio and transferred into 8-week-old Rag2−/− mice. After 96 h, CellTrace dilution analysis was performed; i.v., intravenous. b, Proportions and CellTrace fluorescence of CD45.1+ FLOX and CD45.2+ CKO T cells before and 96 h after transfer. Left, representative flow plots. Top right, bar graphs showing the percentages of FLOX and CKO T cells. Bottom right, bar graphs showing the percentages of FLOX and CKO T cells divided more than once; n = 4; ****P < 0.0001. c, Left, representative plots of CFSE staining and side scatters (SSC) of 72-h, anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated FLOX and CKO T cells. Right, bar graphs showing the percentages of CFSElo FLOX and CKO T cells after 72 h of stimulation; n = 3; ****P < 0.0001. d, Cell cycle analysis by BrdU/7-AAD staining of 48-h, anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Top, representative flow plots. Bottom, bar graphs showing the distribution of FLOX and CKO T cells across G0–G1, S and G2–M phases, respectively. n = 4; ****P < 0.0001. e, Apoptosis assessment by Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining of FLOX and CKO T cells in the spleen. Top, representative flow plots. Bottom, bar graphs showing the proportions of live (Annexin V–PI–), early apoptotic (Annexin V+PI–) and late apoptotic (Annexin V+PI+) splenic T cells in FLOX and CKO mice; n = 4. Exact P values from left to right: **P = 0.0041, **P = 0.0040, *P = 0.0197, ***P = 0.0004, ***P = 0.0006 and ***P = 0.0009. f, Apoptosis detection performed the same as in e in the lymph nodes. Left, representative flow plots. Right, bar charts showing the proportions of the indicated populations in FLOX and CKO mice (FLOX n = 3, CKO n = 4). Exact P values from left to right: **P = 0.0031, *P = 0.0137, **P = 0.0021, **P = 0.0050, *P = 0.0293 and **P = 0.0053. n refers to the number of biologically independent samples. Error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. (b–f). Data were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired t-test (b–f).

Source data

NAT10 is required for the stability and translation of Myc mRNA

To investigate the specific mechanism of the observation above, we conducted RNA-seq using RNAs isolated from sorted splenic CD3+ TEFF cells. In total, 1,822 upregulated and 1,586 downregulated mRNAs were identified, with many cell division-related genes, such as Cdk2, Cdk4 and Cdc25a, expressed at lower levels (Fig. 4a). Genes that were decreased in expression showed a significant enrichment in gene ontology (GO) terms related to metabolic processes, indicating compromised metabolism in CKO T cells (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Acetylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (acRIP–seq) was also conducted synchronously to determine NAT10’s role in T cell regulation as an ac4C writer. A total of 67,564 acetylation peaks were identified, with 4,549 downregulated and 4,209 upregulated in CKO T cells compared to in FLOX control T cells (Fig. 4b). mRNAs with significantly reduced ac4C levels showed a high enrichment in pathways related to cell proliferation, RNA regulation and cellular anabolism (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Metagene analysis showed similar global ac4C distributions between the two groups, with acetylated peaks enriched in the vicinity of the coding sequence in mRNAs (Fig. 4c). Bringing these two sequencing data sets together, we found that 772 transcripts showed both lower ac4C modification levels and mRNA expression levels, and these transcripts were highly enriched in pathways mainly related to cellular metabolism, nucleocytoplasmic transport, DNA replication and so on (Fig. 4d,e). The combined analysis indicated that ac4C-modified transcripts presented a global tendency toward decreased expression following Nat10 deletion compared to those lacking ac4C (Fig. 4f). Allocating to specific transcripts, we found that most of the acetylated mRNAs significantly decreased in expression in response to Nat10 deletion, whereas modification-free transcripts showed a converse bias toward increased expression following ac4C loss (Fig. 4g). Some feedback regulation or indirect mechanisms may play a role.

a, Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes between CKO and FLOX activated TEFF cells, with cutoffs of P ≤ 0.05 and | fold change | ≥ 2; FC, fold change. b, Volcano plot showing differentially acetylated peaks between CKO and FLOX TEFF cells, with cutoffs of P ≤ 0.00001 and | fold change | ≥ 2. c, Metagene analysis of ac4C sites identified on mRNAs from FLOX and CKO TEFF cells; UTR, untranslated region; CDS, coding sequence. d, Venn diagram showing the numbers of transcriptionally repressed transcripts with significantly fewer modified by ac4C. e, KEGG pathway analysis of the overlapped genes identified in d. f, Cumulative distribution function plot exhibiting differential expression of ac4C+ or ac4C– transcripts between CKO and FLOX TEFF cells. g, Volcano plots of differentially expressed mRNAs between CKO and FLOX TEFF cells segregated by ac4C modification, with cutoffs of P ≤ 0.05 and | fold change | ≥ 2. h, GSEA of ‘MYC targets V1’ between CKO and FLOX TEFF cells; NES, normalized enrichment score. i, Circular heat map showing mRNA levels of MYC-regulated genes in FLOX and CKO TEFF cells. j, MYC, CDC25A, CDK2 and CDK4 protein levels in FLOX and CKO CD3+ TN cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for the indicated lengths of time. Representative bands of three independent experiments are presented. k, IGV plot displaying specific ac4C peaks on Myc transcripts. Peaks are represented as subtracted read densities (IP minus input). l, ac4C RIP–qPCR for Myc mRNA in activated FLOX and CKO CD3+T cells; n = 3; **P = 0.0017. m, Degradation of Myc mRNA in activated FLOX and CKO CD3+ T cells 1 and 2 h after actinomycin D treatment; n = 3; ***P = 0.0003 and **P = 0.0097. n, NAT10 RIP–qPCR for Myc mRNA in activated CKO and FLOX CD3+ T cells; n = 4; ****P < 0.0001. o, Ribosome occupancy of Myc and control mRNAs in activated CKO and FLOX CD3+ T cells; n = 3; ****P < 0.0001. n refers to biologically independent samples. Activated T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 h in l–o. Error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. (l–o). Data were analyzed by two-tailed, negative binomial distribution test (a, b and g); one-sided, hypergeometric test (Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted) (e); two-tailed, Mann–Whitney U-test (f); two-tailed Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (h) and two-tailed, unpaired t-test (l–o).

Source data

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed that ‘MYC transcriptional targets’ was the most prominently downregulated gene set. The vast majority of MYC-regulated genes showed impaired expression in CKO T cells versus in FLOX T cells (Fig. 4h,i). Additionally, significantly downregulated genes were also enriched in DNA replication, cell growth and G1–S transition, suggesting defective growth and expansion processes following NAT10 loss in T cells (Extended Data Fig. 3c). We then measured MYC expression after 0, 6 and 24 h of stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28. Western blotting revealed impaired expression of MYC at the protein level, in addition to the acknowledged MYC targets CDK2, CDK4 and CDC25A (Fig. 4j). How, then, does NAT10 impact MYC protein levels? acRIP–seq visualized by Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV) showed that ac4C peaks were extensively distributed within the Myc mRNA region, and these peaks were all significantly downregulated after Nat10 deletion (Fig. 4k). ac4C-RIP–qPCR further confirmed that Myc mRNA was ac4C modified, and relative enrichment of ac4C peaks was reduced by about 85% in CKO T cells compared to in FLOX control T cells (Fig. 4l). To verify whether this was because of decreased ac4C abundance and subsequent impaired stability of modified transcripts, we adopted an in vitro assay using actinomycin D (a transcription inhibitor) to investigate the speed of Myc RNA decay. We observed that the degradation velocity for Myc was faster for CKO T cells than for FLOX control T cells (Fig. 4m). Except for ac4C, NAT10 protein was also shown to bind to Myc mRNA specifically (Fig. 4n). To further explore the influence of ac4C on mRNA translation within T cells, we performed ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq). Briefly, ribosome-protected fragments (RPFs) were collected, sequenced and projected to the total transcripts shown in the RNA sequence, contributing to measuring ribosome density, namely translation efficiency (TE). T cell transcripts were classified into two categories, ac4C+ and ac4C–, according to the presence or absence of ac4C peaks revealed by ac4C RIP–seq. The sequencing data showed that ac4C+ transcripts manifested markedly higher TE than ac4C– transcripts, guaranteeing efficient protein synthesis in CD3+ T cells (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Furthermore, compared to FLOX control T cells, TE of ac4C– mRNAs stayed unchanged, whereas that of ac4C+ transcripts showed a significant decrease in CKO T cells, indicating that Nat10 KO ablated the elevation of TE due to ac4C modification in T cells (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Focusing on Myc mRNA, we performed polyribosome real-time PCR and found a dramatic decrease in the accumulation of ribosomes on Myc but not on control transcripts in CKO T cells (Fig. 4o). In summary, NAT10 promotes the synthesis of MYC protein by facilitating mRNA stability and translation.

Nat10 deletion causes metabolic dysfunction of T cells

Except for direct MYC transcriptional targets, the related metabolic gene sets were also significantly compromised at the transcription level (Extended Data Fig. 4a). According to ‘Compass’ analysis, an algorithm that evaluates the metabolic state of cells based on scRNA-seq data, cellular metabolism was broadly impaired in CKO T cells17. Metabolic reactions, including nucleotide, lipid, carbonhydrate, amino acid and energy metabolism and so on, showed significantly decreased activity in response to NAT10 loss (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Adequate supplies and instant reprogramming in metabolism are both critical for T cell activation and expansion. We next performed ultraperformance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS) analysis of FLOX and CKO TN cells as well as their activated counterparts to see if NAT10 deficiency impaired this intricate metabolic network. We observed that levels of most nucleotides, amino acids and fatty acids were robustly elevated in stimulated FLOX T cells. However, this metabolic reprogramming was compromised after Nat10 deletion (Extended Data Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Additionally, decreased glucose uptake and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) suggested lower levels of glycolysis during activation in CKO T cells (Extended Data Fig. 4e,f). Reduced oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and ATP production in both CKO TN and TEFF cells suggest dysfunctional energy supplies in T cells without NAT10 support (Extended Data Fig. 4f,g). That is, metabolic dysfunction due to NAT10 deficiency fails to fuel the robust biosynthesis required for activation-induced cell growth and proliferation in CKO T cells.

NAT10 overexpression rescues proliferative defects in CKO T cells

To verify the contribution of the NAT10–MYC axis to the phenotypes of CKO T cells, we constructed bone marrow chimeric mice with hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from FLOX and CKO mice, respectively. NAT10 or MYC was overexpressed in CKO HSCs via retroviruses, and negative control plasmids were also transfected into HSCs from both groups as baseline controls. Treated HSCs accompanied with moderate protectors were then transferred into irradiated CD45.1+ mice (Fig. 5a). Ten weeks later, CD45.2+ T cells derived from retrovirus-infected HSCs were identified for further analysis. Overexpression in T cells was validated by western blotting (Fig. 5b). NAT10 overexpression efficiently reverted the T cell pool (Fig. 5c). More importantly, the proliferative defect following TCR stimulation in CKO T cells was effectively compensated by NAT10 or MYC restoration (Fig. 5d,e). The same was true for protein synthesis potency (Fig. 5f). Together, these data demonstrate that the proliferative and metabolic defects in CKO mice were largely dependent on the NAT10–MYC axis, suggesting its critical role in T cell maintenance and expansion.

a, Schematic diagram showing construction of bone marrow chimeric mice. CD117+ enriched HSCs from 8-week-old FLOX and CKO mice were infected with control or NAT10- or MYC-overexpressing retrovirus and then transplanted into irradiated 8-week-old CD45.1+ mice. Ten weeks later, CD45.2+ T cells derived from retrovirus-infected HSCs were identified for further proliferation analysis. b, NAT10 and MYC overexpression in CKO T cells was verified by immunoblotting. Representative bands of three independent experiments are presented; NC, negative controls. c, Frequency of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as a proportion of total adoptive cells identified by CD45.2 staining in each group. Left, representative flow plots. Right, bar graphs showing the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from total adoptive cells; n = 3. For data from the spleen, ***(P_{rm{CD8}^+}) = 0.0002, **(P_{rm{CD8}^+}) = 0.0015, *(P_{rm{CD8}^+}) = 0.0488, **(P_{rm{CD4}^+}) = 0.0037 and *(P_{rm{CD4}^+}) = 0.0174. For data from the lymph nodes, ****P < 0.0001, ***P = 0.0005 and **P = 0.0041. d,e, CellTrace dilution analysis of T cells from chimeric mice. T cells labeled by CellTrace were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 72 h and detected via FCM. Representative flow plots are shown on the top (d) or left (e), and bar plots displaying percentages of CellTracelo activated T cells in each group are shown on the bottom (d) or right (e); n = 4; ****P < 0.0001. f, O-propargyl-puromycin (OPP) staining of activated T cells (stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 h) from chimeric mice. Left, representative flow plots. Right, bar plots displaying the percentages of OPP+ T cells in each group; n = 3; ****P < 0.0001. n refers to the number of biologically independent samples. Error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. (c–f). Data were analyzed by two-tailed, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (c–f).

Source data

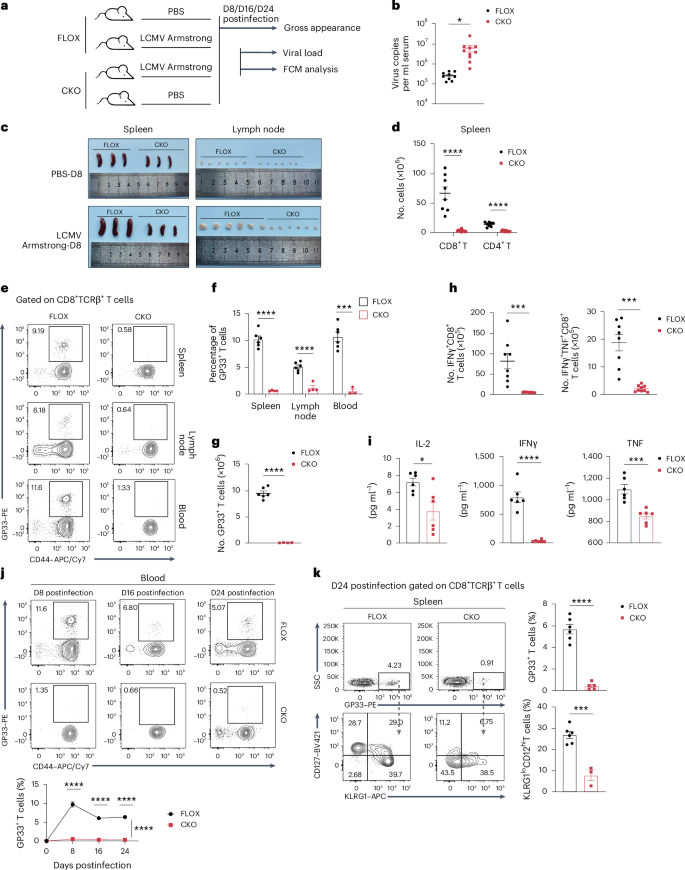

NAT10 matters in T cell antiviral immunity

T cells have long been considered a vital player in antiviral response. The robust expansion capacity serves as an important prerequisite for activated T cells to be excellent virus defenders. Considering NAT10’s core role in T cell proliferation, we next sought to determine whether NAT10 is involved in T cell antiviral potency.

Age- and sex-matched FLOX and CKO mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong as previously described to develop an acute LCMV infection model, with mice injected with PBS serving as controls. Animals were killed at 8, 16 and 24 days after infection (Fig. 6a). Virus load analysis revealed that CKO mice harbored 11-fold higher viral RNA in the serum than FLOX control mice on day 8 after infection, indicating severe antiviral defects of T cells following NAT10 deficiency (Fig. 6b). Additionally, we found that spleens and lymph nodes in FLOX mice were greatly enlarged, suggesting robust proliferation of lymphocytes during virus infection, which was significantly attenuated in CKO mice (Fig. 6c). Consistently, the absolute numbers of splenic CD8+ and CD4+ T cells from CKO mice were also remarkably less (Fig. 6d). To further evaluate the role of NAT10 in T cell responses during virus infection, tetramer staining and FCM were performed on spleen, lymph node and peripheral blood from infected mice. Results showed that the proportion of LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells in the above tissues from CKO mice was significantly lower than that from FLOX control mice (Fig. 6e,f). The absolute number of splenic GP33+CD8+ T cells and functional CD8+ T cells secreting IFNγ and TNF presented a similar variation (Fig. 6g,h). In addition, key cytokines related to virus killing (IFNγ and TNF) and IL-2 in the serum were found at lower levels in CKO mice at 4 and 8 days after infection, respectively (Fig. 6i). At days 16 and 24 after LCMV infection, the proportion of virus-specific T cells in CKO mice was still at a diminished level (Fig. 6j). Twenty-four days after infection, the proportion of the KLRG1loCD127hi subset in GP33+ T cells was also significantly decreased in CKO mice, suggesting impaired memory T cell formation following NAT10 deficiency (Fig. 6k).

a, Schematic of the acute LCMV infection model in FLOX and CKO mice. Eight-week-old FLOX and CKO mice were intraperitoneally injected with 2 × 105 p.f.u. LCMV Armstrong and killed at 8, 16 and 24 days after infection. Animals treated with equal volumes of PBS served as blank controls. Serum, spleens and lymph nodes from the LCMV group were collected for further analysis. b, Viral loads in the serum derived from FLOX (n = 9) and CKO (n = 10) mice at 8 days after LCMV administration; *P = 0.0253. c, Gross appearance of spleens and inguinal lymph nodes from infected FLOX and CKO mice and their blank controls at 8 days after PBS or virus administration. d, Absolute number of splenic CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in FLOX (n = 8) and CKO (n = 10) infected mice at 8 days after infection; ****P < 0.0001. e,f, Percentages of GP33+CD44+ CD8+ T cells in the spleen, lymph node and blood from FLOX (n = 6, 6 and 6) and CKO (n = 4, 4 and 3) infected mice at 8 days after infection; ****P < 0.0001 and ***P = 0001. g, Absolute number of splenic GP33+CD44+ CD8+ T cells from FLOX (n = 6) and CKO (n = 4) infected mice at 8 days after infection; ****P < 0.0001. h, Absolute number of splenic IFNγ+ and IFNγ+TNF+ CD8+ T cells in FLOX (n = 8) and CKO (n = 9) infected mice at 8 days after infection; ****P < 0.0001 and ***P = 0.0006. i, Serum IL-2, IFNγ and TNF (8, 4 and 4 days after infection, respectively) levels in FLOX and CKO infected mice (n = 6); ****P < 0.0001, ***P = 0.0007 and *P = 0.0141. j, Percentages of GP33+CD44+ CD8+ T cells in blood from FLOX (n = 5, 6 and 6) and CKO (n = 3, 5 and 5) infected mice at 8, 16 and 24 days after infection; ****P < 0.0001. k, Percentages of GP33+ CD8+ T cells (FLOX n = 6, CKO n = 5) and KLRG1loCD127hiGP33+ CD8+ T cells (FLOX n = 6, CKO n = 3) from FLOX and CKO infected mice at 24 days after infection; ****P < 0.0001 and ***P = 0.0003. n refers to the number of biologically independent samples. Error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. (b, d and f–k). Data were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired t-test (b, d, f–i and k) or two-tailed, two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (j).

Source data

CD8+ T cells from P14 mice (with transgenic expression of H-2Db-restricted TCR specific for LCMV glycoprotein 33–41) can recognize the LCMV GP33–41 peptide and produce robust LCMV-specific CD8+ T cell responses. We then generated P14 T cells with Nat10 knockdown via retroviruses and transferred the cells to naive WT mice 1 day before LCMV Armstrong infection (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). Three days later, transfected T cells were identified, and remarkable proliferative impairment was observed in Nat10-knockdown P14 T cells (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Seven days after infection, the percentage, absolute number and amplification fold change of P14 T cells were all found to be significantly decreased following NAT10 deficiency (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Functional defenders (TNF+IFNγ+ P14 T cells) exhibited the same trend (Extended Data Fig. 5e).

Together, NAT10 matters in T cell antiviral immunity. Loss of NAT10 causes contraction of the T cell population along with compromised in vivo antiviral responses in mice.

Decreased NAT10 levels in T cells from older individuals may be involved in age-related antiviral defects

Interestingly, we found an age-related differential NAT10 expression in both human immune cells and mouse immune organs. In mice, NAT10 protein levels were significantly diminished in the spleens of 72-week-old mice compared to in 8-week-old young control mice (Fig. 7a). This decrease was also confirmed at the ac4C level (Fig. 7b). We then performed RNA-seq and acRIP–seq in spleens from young (aged 8 weeks) and old (aged 72 weeks) mice to determine changes in ac4C modifications in immune organs during aging and NAT10’s potential role in it (Extended Data Fig. 6a). GO analysis of significantly downregulated genes in old spleens versus in the spleens of young control mice from RNA-seq data sets showed dampened adaptive immune responses and reduced T cell activation in aged mice (Extended Data Fig. 6b). According to the epitranscriptome profiling, the global distribution patterns of ac4C in the spleen as reported were similar between young and old mice (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Additionally, CUWCV and UWYMU were identified ac4C sequence motifs in the spleens of young and old mice, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 6d). To further determine expression changes in response to ac4C loss, we performed combined mRNA-seq and acRIP–seq analyses. Among 630 transcripts with decreased ac4C modifications, 65 were also lower at the mRNA level (Supplementary Table 3). These potential NAT10 targets showed high enrichment in GO analysis terms related to T cells, such as T cell activation, differentiation and proliferation (Extended Data Fig. 6e). These data link NAT10 to age-associated T cell alterations.

a,b, NAT10 protein (a) and ac4C (b) levels in splenocytes from young (8 weeks (8w)) and old (72 weeks (72w)) mice. The bar graph in b shows the relative ac4C intensities normalized to total RNA (200 ng); n = 3; **P = 0.0034. c, NAT10 and MYC expression levels in CD3+ T cells from young (8 weeks) and old (72 weeks) mice stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for the indicated lengths of time. d, CellTrace dilution of 72-h, anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated T cells from young (8 weeks) and old (72 weeks) mice. Left, representative flow plots. Right, bar graphs showing percentages of CellTraceloCD3+ T cells from young and old mice, respectively; n = 3; **P = 0.0088. e, NAT10 and MYC protein levels in 48-h, anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated PBMCs from healthy young (<60 years old, three men and two women) and older (≥60 years old, three men and two women) adults. f, CFSE dilution of 72-h, anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated CD3+ T cells from young (<60 years old) and older (≥60 years old) healthy donors. Left, representative flow plots. Right, bar graphs showing percentages of CFSEloCD3+ T cells in young (n = 5) and older (n = 4) healthy donors; *P = 0.0218. g,h, Box plots showing NAT10 and MYC expression between none-severe and severe groups of the same age category (g) or between young (<60 years old) and older (≥60 years old) groups with similar disease severity (h; young none-severe n = 26, young severe n = 16, old none-severe n = 23, old severe n = 33). Boxes show median and top and bottom quartiles, whiskers show 1.5× interquartile range on either side, and points show independent samples. i, Correlation analysis between NAT10 and MYC expression in individuals with COVID-19; n = 98. j, Correlation analysis between APACHEII scores and NAT10 and MYC expression in individuals with COVID-19; n = 56. k, NAT10 expression across clusters identified in Extended Data Fig. 6i. l, Proportions of CD8+ proliferating T cells in young none-severe (n = 14), old none-severe (n = 4), young severe (n = 8) and old severe (n = 5) individuals, respectively. n refers to the number of biologically independent samples. Representative data from three independent experiments are presented (c and e). Error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. (b, d and f). Data were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired t-test (b, d, f–h and l) or two-tailed, Pearson correlation method (i and j); TCM, central memory T cell; MAIT, mucosal-associated invariant T cells; Treg, regulatory T cells; TEM, effector memory T cells; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocytes.

Source data

Next, to determine NAT10 expression in T cells at different ages more specifically, we purified CD3+ splenic T cells from young (8-week-old) and old (72-week-old) mice and stimulated them with anti-CD3/CD28 for the indicated lengths of time. Western blot analysis suggested that NAT10 was downregulated in T cells from old mice (Fig. 7c). Changes in MYC protein expression showed a similar trend, as did MYC expression in CKO T cells (Fig. 7c). Additionally, an identical proliferation defect was also observed in T cells from aged mice (Fig. 7d).

In humans, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from older (≥60 years old) and younger (<60 years old) healthy donors were purified by Ficoll gradient centrifugation and stimulated by treatment with anti-CD3/CD28 in the presence of IL-2 for 48 h (Extended Data Fig. 6f). These populations, over 75% of which were T cells, were then analyzed by western blotting (Extended Data Fig. 6g). Results showed that NAT10 protein expression was attenuated in activated T cells from older individuals compared to in activated T cells from young control individuals, with MYC showing a similar trend (Fig. 7e). Expansion of T cells obtained from older individuals was also impaired (Fig. 7f).

It is well known that older individuals are usually more susceptible to viral infection than those that are younger, with longer duration and more severe symptoms, which is largely related to aging of the immune system18. To further inspect if NAT10 plays a parallel role in human antiviral responses, as it does in our mouse model, we reanalyzed published RNA-seq data from leukocytes derived from individuals with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)19. A total of 98 individuals were included, with 3 excluded for missing age data and 1 excluded as an outlier (with NAT10 and MYC expression values outside the mean ± 2.5 s.d.). In this cohort, individuals with mild or moderate symptoms were admitted to the hospital with only supportive care, whereas those with critical symptoms were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Therefore, we placed individuals not in the ICU in the ‘none-severe’ group (n = 49) and placed individuals in the ICU in the ‘severe’ group (n = 49), as in other studies20. Fifty-six of the 98 individuals were older (>60 years old), and the others belonged to the young group (≤60 years old; n = 42). Results showed that individuals with serious COVID-19 symptoms expressed lower levels of NAT10 and MYC in both young and old groups (Fig. 7g). Additionally, consistent with our in vitro data, NAT10 and MYC were also expressed at lower levels in older individuals than in younger individuals in both none-severe and severe groups (Fig. 7h). Pearson’s correlation analysis suggested that NAT10 protein levels were significantly positively correlated with MYC expression (Fig. 7i). The APACHEII score is widely used to assess disease severity and prognosis, with a higher score indicating a more critical condition. Among the participants, we observed a significant inverse correlation between NAT10 expression and severity of clinical symptoms (Fig. 7j). The same was true for MYC (Fig. 7j). Thus, NAT10 expression in leukocytes is negatively associated with age and severity. However, it remains unknown how it works. Numerous factors may be involved in this process. For example, it is recognized that individuals with severe COVID-19 show marked decreases in lymphocyte populations21. Decreased NAT10 abundance may contribute to this lymphopenia, and alterations in lymphocytes may also in turn impact NAT10 levels in individuals with severe disease. These intricate relationships await to be further elucidated.

To further investigate the role that NAT10 plays in human antiviral responses, we reanalyzed published COVID-19 scRNA-seq data22, with 41 personal samples included. These individuals were classified into healthy (WHO score of 0), none-severe (WHO score of 1–5) and severe (WHO score of 6–8) groups22 and partitioned into young (<60 years old) and old (≥60 years old) groups by age. Around 110,000 thousand high-quality single cells were obtained in total, and 14 cell clusters were derived after UMAP dimension reduction analysis, covering diverse cell types in peripheral blood (Extended Data Fig. 6h). Natural killer cells and T cells were then purified for deeper analysis, with 18 clusters displayed at a higher resolution (Extended Data Fig. 6i). We next compared NAT10 expression at the transcript level across all subpopulations. As we expected, NAT10 was most highly expressed in proliferating T cells (Fig. 7k). In addition, we found that both in cases of none-severe and severe COVID-19, older individuals exhibited a significant reduction in CD8+ proliferative T cells compared to younger individuals (Fig. 7l). Reports have indicated that there may be considerable differences in immune status among individuals with varying degrees of symptom severity. T cells can be profoundly depleted for strong antiviral responses in individuals with severe disease23. Acute lymphopenia serves as a strong signal to induce T cell proliferation, and perhaps that is part of what causes increasing numbers of proliferative T cells in individuals with severe disease24,25. Elevated numbers of proliferating populations may help to maintain the T cell pool against severe COVID-19. However, this increase of proliferating subsets induced by symptom exacerbation is significantly reduced in the older population, which may be partially responsible for their impaired antiviral responses against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

NAT10 overexpression restores proliferation and antiviral defects in T cells from older individuals

Given the role of the NAT10–MYC axis in age-associated antiviral decline, we next explored whether NAT10 or MYC overexpression in old T cells could reverse their impaired expansion capacity. T cells with retroviral infection were identified by green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression for further analysis. Overexpression efficiency was verified by western blotting (Fig. 8a). As expected, protein levels of MYC targets were efficiently upregulated in T cells from old mice following NAT10 restoration (Fig. 8a). CellTrace dilution analysis and Ki-67 staining indicated that NAT10 or MYC overexpression could functionally compensate for proliferative defects in aged T cells (Fig. 8b,c). Additionally, the decrease in metabolic activity was also reverted. Significant reductions in glucose consumption, lactate production, ATP generation and protein synthesis in T cells from aged mice were all recovered by NAT10 or MYC restoration to different degrees (Fig. 8d–g). Thus, NAT10 or MYC overexpression can efficiently improve both proliferative and metabolic defects in T cells from older animals.

a, NAT10 and MYC overexpression in T cells from aged mice. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown. Y, young; O, old; w, weeks. b,c, CellTrace dilution analysis (b) and Ki-67 expression (c) in T cells from aged mice with NAT10 or MYC overexpression. Left, representative flow plots. Right, bar diagrams showing the percentage of CellTracelo (b) or Ki-67+ (c) T cells in each group; n = 5 (b) and n = 4, 3, 4 and 4 (c). Exact P values from left to right: **P = 0.0052, *P = 0.0315 and **P = 0.0065 (b) and ****P < 0.0001, ***P = 0.0005 and ***P = 0.0001 (c). d–f, Glucose consumption (d), lactate production (e) and ATP generation (f) in T cells from aged mice with NAT10 or MYC overexpression; n = 5, 6 and 4. Exact P values from left to right: *P = 0.0115, **P = 0.0048 and *P = 0.0122 (d), ***P = 0.0001, ***P = 0.0001 and ***P = 0.0006 (e) and **P = 0.0081, **P = 0.0086 and ****P < 0.0001 (f). g, OPP staining of T cells from aged mice with NAT10 or MYC overexpression. Left, representative flow plots. Right, bar diagrams showing the percentage of OPP+ T cells in each group; n = 3; ***P = 0.0010, **P = 0.0073 and *P = 0.0428. h, Flow chart of experiments exploring the impact of NAT10 restoration on T cell antiviral potency. CD8+ T cells from old P14 mice with control or Nat10-overexpressing plasmids were transferred into 8-week-old Rag2−/− mice 1 day before LCMV infection. Eight days later, antiviral analysis was performed. i, Serum viral loads of recipients at 8 days after LCMV infection; NC n = 6, Nat10 overexpression (OE) n = 5; *P = 0.0424. j, Proportions of GFP+ P14 T cells in recipients. Left, representative flow plots. Right, bar diagrams showing the expansion fold changes of GFP+ P14 T cells in each group; NC n = 6, Nat10 overexpression n = 5; *P = 0.0195. k, Detection of IFNγ+TNF+GFP+ CD8+ T cells in recipients. Left, representative flow plots. Right, bar diagrams showing the absolute number of splenic IFNγ+TNF+GFP+ CD8+ T cells in the two groups; NC n = 6, Nat10 overexpression n = 5; *P = 0.0415. n refers to the number of biologically independent samples. Error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. (b–g and i–k). Data were analyzed by two-tailed, one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (b–g) or two-tailed, unpaired t-test (i–k).

Source data

Further, the in vivo LCMV infection model was applied to investigate if NAT10 upregulation could improve the antiviral responses of aged T cells. CD8+ T cells obtained from old P14 mice with control or Nat10-overexpressing plasmids were transferred into Rag2−/− mice 1 day before LCMV infection (Fig. 8h). According to our results, recipients with NAT10-overexpressing P14 T cells harbored lower viral RNA levels in serum than their control counterparts on day 8 after LCMV infection (Fig. 8i). Additionally, NAT10-overexpressing P14 T cells were found to amplify at a higher rate and contained more functional defenders (TNF+IFNγ+ T cells; Fig. 8j,k). That is to say, NAT10 restoration efficiently recovered age-induced compromised antiviral responses. Therefore, NAT10 might be another promising target for immunotherapy, especially in older individuals.

Discussion

Here, we present evidence that ac4C functions as a form of epigenetic translational control, providing a crucial mechanism driving the rapid proliferation of activated T cells. Translation stands out as an active process in the early stages of T cell activation, and through the use of genetic mouse models, PBMC samples, high-throughput ac4C RIP–seq, mRNA sequencing and Ribo-seq, the following key findings emerged: (1) expression of ac4C proteins, particularly NAT10, undergoes a rapid increase following T cell activation within a very short timeframe; (2) TCR signaling activates NAT10-mediated ac4C processing during T cell activation via c-JUN; (3) ac4C modification acts as an essential translational checkpoint, stabilizing Myc mRNA and acting as a ‘shield’ for T cell activation and proliferation; and (4) diminished expression of NAT10 during aging is associated with the antiviral immunity of T cells.

Research efforts directed toward other epitranscriptomic modifications carry exemplary significance for furthering our understanding of ac4C dynamics in this context7,26,27. When Arango et al. first identified NAT10 as the ac4C writer, they described NAT10-deficient cells as highly viable, with reduced proliferation kinetics and a tendency for cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase compared to WT control cells. Their sequencing data support this phenotype as genes altered after Nat10 knockout were closely associated with cell survival and proliferation28. Later investigations further clarified the importance of NAT10 for cell division. Both mitosis of cancer cells29 and meiosis of male germ cells30 were found to be governed by NAT10-dependent machinery. Indeed, after deleting Nat10 in T cells in vivo, we observed a marked shrinkage of the T cell pool in both immune (spleen and lymph nodes) and other parenchymatous organs (lung and kidney). Considering the extensive contraction of peripheral T cells in response to NAT10 deficiency, we speculate that the influence of ac4C on T cells may largely situate in signaling pathways responding to environmental stimuli. It has also been extensively reported that NAT10-mediated ac4C modification is involved in ribosome biogenesis31,32. In our scRNA-seq data, we also observe the same trend. However, in the context of this study, abnormal ribosomal protein expression may be attributed, in part, to impaired MYC expression because MYC is also a well-known regulator that promotes ribosome biogenesis32,33.

Remarkably, despite ac4C’s emergence as a crucial aspect of epitranscriptomic regulation in RNA metabolism, its alterations at the tissue level during aging remain unexplored. In this study, we examined the ac4C landscapes within the spleen and found a close association between age-related ac4C loss and impaired T cell proliferation and differentiation. These findings suggest that the decrease in ac4C modification observed during aging may contribute to T cell aging. However, given the multifactorial nature of immune senescence, it is important to acknowledge that ac4C modifications likely operate alongside other regulatory mechanisms affecting immune functionality during aging. Further research is needed to clarify the interplay between these pathways. Considering the utility of DNA methylation in aging prediction34, it would be equally intriguing to explore whether ac4C modification could be harnessed to establish an aging biomarker in the future. Additionally, our observation of older individuals with COVID-19 harboring fewer proliferating T cells in response to infection with SARS-CoV-2 raises intriguing questions. Future studies should explore how NAT10 and ac4C impact age-related antiviral immunity and the diminished ability to combat infections in greater detail. This study presents two key limitations that warrant further investigation. Specifically, (1) it is unclear what causes T cells to become hyperactive in the absence of NAT10, and (2) the regulation of T cells by NAT10 within the context of disease is intricate; therefore, it remains to be determined how NAT10 regulation interacts with COVID-19 severity and lymphopenia and whether they interfere with or support one another.

To date, whether this ac4C writer protein participates in harnessing T cell development and function remains largely unknown. Here, we investigated the involvement of NAT10 in the maintenance of T cell expansion. Linked with the interesting observation that ac4C modifications are decreased in individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus4, our findings shed light on the crucial role of ac4C mRNA modification in immune cell homeostasis and proliferation, opening avenues for exploiting the function of ac4C in immune responses and immune deregulation.

Methods

Human samples

In this study, PBMCs were isolated from the blood of healthy donors and used to perform FCM or western blotting. All participants were recruited from Jinshan Hospital with written informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinshan Hospital (JIEC 2023-S47). Healthy donors were defined as (1) aged 18–85 years old, (2) no infectious diseases over the past 6 months, (3) no malignant tumor history and (4) no history of autoimmune disease. Routine blood examinations were performed to ensure the quality and eligibility of each donor. Samples from a total of six men and four women were collected, with 2–3 ml whole blood obtained from each participant.

Mice

Six- to 8-week-old C57BL/6J WT mice were purchased from SPF Biotechnology. Seventy-two-week-old C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jiangsu Huachuang Sino Pharma Tech. FLOX mice were gifted from Y. Lu (Shanghai Jiao Tong University). Cd4Cre mice were purchased from Cyagen Biosciences. To generate Nat10-CKO mice, FLOX mice were crossed with Cd4Cre mice. P14 mice were a gift from the laboratory of L. Ye (Army Medical University). Rag2−/− mice were purchased from Cyagen Biosciences. Mice were housed and routinely handled in Cyagen Biosciences and Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center under specific pathogen-free conditions following institutional guidelines. All mice were fed with standard mice chow (specific pathogen free, SPF-F02-002). Animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center (2023-A053-01).

T cell isolation and culture

Naive or total CD3+ T cells were purified using an EasySep Mouse Naive T Cell Isolation kit (STEMCELL Technologies) or a MojoSort Mouse CD3 T Cell Isolation kit (Biolegend) according to the respective instructions. In vitro-activated CD3+ T cells were generated by stimulating naive CD3+ T cells with plate-bound anti-CD3ε (Biolegend, clone 2C11; 5 μg ml–1) and dissolvable anti-CD28 (eBioscience, clone 37.51; 0.5 μg ml–1) in the presence of IL-2 (PeproTech; 100 U ml–1). Naive CD3+ T cells labeled with CFSE (BD Pharmingen) or CellTrace (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were stimulated for 72 h. CFSE or CellTrace dilutions were used to assess cell proliferation. For cell cycle analysis, naive CD3+ T cells were stimulated for 48 h, followed by BrdU/7-AAD double staining using a FITC BrdU Flow kit (BD Pharmingen), as per the manufacturer’s protocol. For RNA-seq and ac4C RIP–seq, cells were washed twice after 72 h of stimulation, transferred to a new plate and cultured for another 3 days in the presence of 100 U ml–1 IL-2 only to obtain enough activated T cells. The medium used contained RPMI-1640, 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich) and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich).

Human PBMC isolation and culture

Human PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll gradient centrifugation of fresh blood as previously described35. The PBMCs were seeded into 24-well plates and stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ε (Biolegend, clone OKT3; 5 μg ml–1) and dissolvable anti-CD28 (Biolegend, clone CD28.2; 1 μg ml–1) in the presence of human recombinant IL-2 (PeproTech; 200 U ml–1). After 48 h, cells were collected for FCM and western blotting. The medium used in this culture system contained X-VIVO-15 serum-free hematopoietic cell medium and 5% fetal bovine serum.

LCMV infection

LCMV Armstrong strain was a gift from L. Ye. Virus was propagated, and titers were measured as previously described36. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 2 × 105 p.f.u. virus to establish an acute infection.

For the adaptive transfer model, 2 × 105 P14 T cells transfected with control or Nat10-overexpressing plasmids were transferred to Rag2−/− recipients, respectively. A total of 4 × 105 p.f.u. LCMV Armstrong was administrated to each recipient 24 h later, and 4 × 105 P14 T cells with Nat10 knockdown and their negative controls were transfected into WT mice 1 day before constructing the acute LCMV infection model. Seven to 8 days later, recipients were killed for further analysis.

Viral load measured by real-time qPCR

RNA was extracted from 140 μl of serum using a QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit (Qiagen). Measurement of viral load by real-time qPCR was performed as previously described37. cDNA was synthesized by using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara). qPCR was performed with Premix Ex Taq (Takara) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Standard curves were generated using serial dilutions of a plasmid template containing a 411-bp gene fragment derived from Armstrong NP open reading frames. Probe, primer and fragment template sequences are available in Supplementary Table 4.

Sample preparation and FCM

Spleen, thymus, lymph node, lung, kidney and liver tissue were collected and ground through 70-μm filters (WHB Scientific). Erythrocytes were lysed with red blood cell lysis buffer (Solarbio), and remaining cells isolated by centrifugation were stained for subsequent FCM analysis. For viability staining, cells were stained with Fixable Viability Stain 510 (BD Pharmingen) in PBS (1:600) at room temperature for 15 min. For cell surface staining, cells were stained with antibodies in cell staining buffer (1:200) at 4 °C for 30 min. For intracellular staining, cells were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate/ionomycin (BioLegend) for 5 h at 37 °C, and intracellular cytokine staining was performed using a Transcription Factor Buffer Set (BD Pharmingen) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Notably, when it comes to functionality detection of T cells from LCMV-infected mice, cells were incubated with GP33–41 peptide (2 μg ml–1; Absin) in the presence of brefeldin and monensin. Absolute counts for lymphocytes were calculated based on FCM gating and total number of splenic or lymph node cells. Apoptosis assays were performed with a FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For cell cycle analysis, BrdU/7-AAD double staining was performed with a FITC BrdU Flow kit (BD Pharmingen), as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were acquired on a BD FACSLyric Cytometer. All data analysis was performed using FlowJo 10.4 software (FlowJo). Sorting assays were performed using a FACS Aria Cytometer (BD Bioscience). Gating strategies are presented in Extended Data Fig. 7.

In vivo T cell proliferation assay

In this study, we used CellTrace dyes to monitor cell proliferation and division by FCM. Naive CD3+ T cells from FLOX (CD45.1+) and CKO mice (CD45.2+) were purified as described above, labeled with CellTrace (Thermo) and mixed at a 1:1 ratio. One million cells were then transferred into each Rag2−/− recipient mouse intravenously. CellTrace dilution of donor cells in recipients was assessed before and 96 h after transfer by FCM.

NAT10/MYC overexpression in vivo

Bone marrow chimeric mouse models were constructed as previously described38. Briefly, FLOX and CKO donors (CD45.2+) were intraperitoneally administrated with 5-fluorouracil (Sigma-Aldrich) prepared in PBS at a dose of 150 mg per kg (body weight). After 24 h, HSCs were enriched from bone marrow cells with a CD117+ selection kit (Stem Cell Technologies) and then incubated with retroviral supernatants containing MIGR1 plasmids for spin infection, as previously described. During HSC transfection, recipient mice (CD45.1+) were sublethally irradiated (9 Gy), and protectors were collected from untreated normal mice (CD45.1+CD45.2+). HSCs and protectors were then both suspended to 5 × 106 cells per ml and mixed at a 1:1 ratio. Next, each recipient was intravenously administered with 0.2 ml of cell suspension (total of 1 million cells). The proliferation status of CKO T cells with control or Nat10– or Myc-overexpressing plasmids was assessed compared to FLOX control mice 10 weeks later.

Metabolomics profiling

Q300 service was provided by Metabo-Profile Biotechnology. Naive and 24-h-activated CD3+ T cells were collected and stored in microcentrifuge tubes. Absolute quantification of intracellular metabolites was performed using a Q300 kit (Metabo-Profile) as previously described39. Briefly, cells were homogenized using ten zirconium oxide beads with 20 µl of deionized water. After methanol (150 μl) containing internal standard was added, the samples were homogenized for the second time and centrifuged at 18,000g for 20 min. The supernatants were then transferred to a 96-well plate, mixed with 20 µl of newly prepared derivative reagents for further derivatization at 30 °C for 60 min and evaporated for 2 h. After that, the samples were diluted with 330 μl of ice-cold 50% methanol, held at −20 °C for 20 min and centrifuged at 4,000g at 4 °C for 30 min. In total, 135 μl of supernatant with 10 μl of internal standards per sample was transferred into a new 96-well plate. Serial dilutions of the standard were added, and the plate was sealed for further LC–MS/MS analysis. All of the standards (Sigma-Aldrich, Steraloids, TRC Chemicals) were accurately weighed and prepared in appropriate solvents to obtain a 5 mg ml–1 stock solution. As for instrumentation, a UPLC–MS/MS system (Acquity UPLC-Xevo TQ-S, Waters) was used to quantify the targeted metabolites. For data processing, the raw data were processed via the iMAP platform (v1.0; Metabo-Profile)40. Contents of detected metabolites are displayed in Supplementary Table 1.

Targeted quantification of nucleotides was also performed by Metabo-Profile Biotechnology. Naive and 24-h-activated CD3+ T cells were collected and stored in microcentrifuge tubes. Each sample was combined with 200 μl of precooled 80% methanol–water and crushed by ultrasound three times at 2% power for 5 s (JY92-IIN, NingBo Scientz Biotechnology). Centrifugation was performed at 4 °C at 18,000g for 20 min (Microfuge 20R, Beckman Coulter). Sixty microliters of supernatant from each sample was transferred to the sample bottle and awaited sample loading. Blank control samples and quality control samples were treated similarly. Serial dilutions of the standard were also added into the plate for further LC–MS/MS analysis. All of the standards (Sigma-Aldrich, Steraloids, TRC Chemicals) were accurately weighed and prepared in appropriate solvents to obtain 5 mg ml–1 stock solutions. For instrumentation, a UPLC–MS/MS system (Acquity UPLC-Xevo TQ-S, Waters) was used to quantify nucleotides in each sample. For data processing, the raw data were processed with MassLynx software (v4.1; Waters) and analyzed on an iMAP platform (v1.0; Metabo-Profile). Contents of detected nucleotides are displayed in Supplementary Table 2.

Glucose uptake measurements

TN cells were purified from 8-week-old FLOX and CKO mice, with anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation for 24 h. After being incubated with glucose-free RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) for 4 h, cells were then treated with 2-NBDG for 30 min. Glucose uptake was assessed by FITC fluorescence intensity via FCM detection. For CKO and T cells from aged mice with NAT10 overexpression, glucose consumption was measured to replace the 2-NBDG for the conflicted fluorescence color. Briefly, 1 × 106 T cells were suspended with 1 ml of fresh complete medium and cultured as normal. One milliliter of medium without T cells was used as a blank control. Twenty-four hours later, the culture medium of each group was collected for glucose content detection by using a Glucose Assay kit (Beyotime). Glucose consumption could then be calculated as the difference between the samples and blank controls.

Metabolism assays

Real-time cell metabolic flux analysis was performed on an XF-96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). A total of 5 × 105 FLOX or CKO T cells were plated into each well of a culture microplate and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in the absence of CO2 in unbuffered RPMI with 1% bovine serum, 1 mM pyruvate, 2 mM l-glutamine and 10 mM glucose. Half of the cells in each group were supplemented with an equal amount of anti-CD3/CD28 beads (5 × 105 cells per well). ECAR and OCR were then measured under basal conditions.

ATP measurements

TN cells were purified from 8-week-old FLOX and CKO mice, some of which were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 h. ATP production in FLOX-TN, CKO-TN, FLOX-TEFF and CKO TEFF cells was measured using an ATPlite 1step Luminescence Assay (PerkinElmer), as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Protein synthesis assays

Cells were prepared according to experimental targets. OPP staining and detection were then performed using a Click-iT Plus OPP Alexa Fluor 647 Protein Synthesis Assay kit (Thermo) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Lactate production measurements

T cells (1 × 106) were suspended with 1 ml of fresh complete medium and cultured as normal. One milliliter of medium without T cells was used as a blank control. Twenty-four hours later, the culture medium of each group was collected for lactate content detection. Lactate production could then be detected using a CheKine Micro Lactate Assay kit (Abbkine) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA ac4C dot blot

Purified RNA diluted to the indicated concentrations was incubated at 95 °C for 3 min, and equal volumes of RNA samples were transferred onto two nitrocellulose membranes, respectively. After air drying for 20 min, the RNA samples were cross-linked to the membranes by UV radiation with a dose of 5 J three times. One membrane was incubated with methylene blue (0.02% in 0.3 M sodium acetate) and washed with double-distilled water for 1 h to obtain the loading control. The other membrane was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin and incubated with anti-ac4C (Abcam) overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with secondary antibody (Proteintech) for 90 min at room temperature. Finally, blot signals were detected using a ChemiScope 6100 (Clinx Science Instruments). Densitometry analysis was performed using ImageJ v.1.53a software.

RIP–qPCR

The ac4C RIP assay was performed using a GenSeq ac4C RIP kit (GS-ET-005, Cloudseq Biotech) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. In detail, total RNA (100 µg) was randomly digested into 100- to 200-bp fragments and incubated with a mixture of 5 µg of anti-ac4C or IgG and magnetic beads. Anti-ac4C-bound RNAs were purified, and enrichment of Myc mRNA was determined by qPCR with reverse transcription. For the NAT10 RIP assay, primary anti-ac4C was replaced with anti-NAT10, with the other procedures unchanged. The primers used are listed in the Supplementary Table 4.

ChIP–qPCR

WT naive CD3+ T cells were isolated and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 h. The ChIP assay was performed using a ChIP assay kit (Cell Signaling Technology). qPCR was then conducted to confirm c-JUN binding to Nat10 loci. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

RNA degradation assay

Naive CD3+ T cells were isolated and stimulated as previously described for 24 h and then treated with 2.5 μg ml–1 actinomycin D for 0, 1 and 2 h. Total cellular RNA was then collected. The relative transcriptional expression of Myc was determined by qPCR with reverse transcription.

Ribo-seq

Ribo-seq was provided by CloudSeq Biotech. Isolated CD3+ FLOX and CKO T cells were mixed with medium containing 0.1 mg ml–1 cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich) softly and centrifuged at 200g for 5 min. After supernatants were removed, cells were resuspended with prechilled PBS containing 0.1 mg ml–1 cycloheximide and transferred to prechilled microcentrifuge tubes, followed by another centrifugation. T cells were then lysed using lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4), 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 100 μg ml–1 cycloheximide and 2% NP-40), and cell lysates were digested by RNase I to obtain RPFs. After rRNA removal using a Ribo-zero kit (Illumina), a repertoire of short RPFs (20–38 nucleotides) were purified by PAGE. 5′ starts and 3′ ends of the RPFs were subsequently phosphorylated and ligated to adapters. cDNA synthesized via reverse transcription was PAGE purified again and amplified by PCR to prepare initial libraries. After PAGE purification for the third time, the cDNA libraries containing 140- to 160-bp fragments were subjected to an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 instrument for sequencing. For data analysis, filtered clean reads were aligned to the reference genome (UCSC hg19) using TopHat2 software41. The number of reads was counted using HTSeq42, and differentially expressed genes were analyzed using DESeq2 software43, with a cutoff of an adjusted P value of <0.05 and | log2 (fold change) | of >1.

Polyribosome real-time PCR

Naive CD3+ T cells were isolated from FLOX and CKO mice, activated as previously described for 24 h and then incubated with cycloheximide (100 μg ml–1; Med Chem Express) for 5 min. Cells were then collected and washed with prechilled PBS (containing 100 μg ml–1 cycloheximide). After lysis, one-third of the lysate was set aside as input, and the remainder was gently added to the sucrose gradient buffer, followed by centrifugation at 274,000g for 1.5 h at 4 °C. Gradient fractions were then collected via Biocomp Piston Gradient Fractionator. RNase inhibitor (Beyotime) was added to the entire liquid system at a final concentration of 1,000 U ml–1. RNAs from polyribosome fractions and input were purified with an RNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo Research) for further qPCR analysis.

Plasmid construction, virus production and virus infection

The Nat10 overexpression plasmid and Myc overexpression plasmid were constructed based on retroviral vectors pMXs-IRES-GFP (a gift from J. Jin, Fudan University) or MIGR1-IRES-GFP (a gift from H. Hu, Sichuan University) via homologous recombination. The Nat10-knockdown plasmid was built from LMP-IRES-AmCyan (a gift from J. Jin). A ClonExpress II One Step Cloning kit (Vazyme), 2× Phanta Max Master Mix (Vazyme) and Trellef DNA Gel Extraction kit (safe & convenient; Tsingke) were used in this procedure. Plasmids were sequence confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Genewiz) and amplified using DH5α competent cells (Tsingke). To generate retroviral particles, Plat E (a gift from J. Jin, for pMXs and LMP plasmids) or 293T cells (for MIGR1 plasmids) were transfected with plasmids along with Lipo6000 (Beyotime). Forty-eight hours later, supernatants including 10 μg ml–1 Polybrene (Beyotime) were filtered and mixed with prepared T cells or HSCs. The mixtures were then spun at 800g for 2 h at 33 °C and left undisturbed for 3 h in an incubator at 37 °C. Cells were then moved to fresh culture medium or were collected for subsequent treatments. Successfully infected cells were distinguished by fluorescence via FCM.

acRIP–seq

The acRIP-Seq service was supported by CloudSeq Biotech. Total RNA was extracted from flow-sorted FLOX and CKO TEFF cells, with rRNA removed using a Ribo-zero kit (Illumina). ac4C-IP was then performed using a GenSeq ac4C-IP kit (GenSeq), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, RNA was fragmented into pieces smaller than 200 nucleotides with RNA fragmentation reagents. Protein A/G beads were conjugated to anti-ac4C via incubation with gentle rotation at room temperature for 1 h. Fragmented RNA samples were incubated with the antibody-prebound beads with rotation at 4 °C for 4 h. IPs were then treated with Proteinase K, and the eluted RNA was recovered by phenol/chloroform extraction. RNA libraries were then constructed with an NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep kit (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Newly established libraries were checked using an Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100 system and sequenced on the NovaSeq platform (Illumina). Raw sequencing reads from an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencer were quality controlled by Q30 and processed with Cutadapt software44 (v1.9.3) to trim the 3′ adaptor and remove low-quality alignments. The filtered clean reads were then aligned to the reference genome with HISAT2 software (v2.0.4)45. ac4C-enriched regions (peaks) were identified by MACS software46, and differentially acetylated sites were identified with diffReps47. The peaks pinpointed earlier that overlapped with exons were identified and chosen by in-house scripts. Genomic distributions of ac4C peaks were visualized using IGV. Motif analysis was performed with the Discriminative Regular Expression Motif Elicitation software according to the default workflow. The metaPlotR package helped to perform the metagene analysis of ac4C sites identified on mRNAs from FLOX and CKO TEFF cells48.

RNA-seq and analysis

In this study, the RNA-seq service was supported by CloudSeq Biotech. Samples of mouse spleen and liver tissues and CD3+ TN and TEFF cells were prepared, and total RNA was extracted. rRNA was removed using an NEBNext rRNA Depletion kit (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA libraries were then constructed with an NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep kit (New England Biolabs) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After quality control and quantification on a BioAnalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies), libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 instrument with paired end reads of 150 bp. After quality control by Q30, the raw data were further filtered via 3′ adaptor trimming using cutadapt software (v1.9.3)44 to obtain high-quality clean reads, which were mapped to the reference genome (UCSC MM10) using HISAT2 software (v2.0.4). HTSeq software (v0.9.1) was then used to generate the raw count, and the edgeR49 package was used to perform normalization and examine differentially expressed genes with a | log2 (fold change) | of ≥ 1 and false discovery rate of ≤0.05. GO and pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the clusterProfiler package49,50. GSEA was performed using the R package AUCell51. For combined analysis, ac4C+ and ac4C– mRNAs were first picked according to acRIP–seq. The ggplots package was then used to calculate the differential expression between the two groups to generate cumulative distribution function plots or within each group to generate volcano plots. For RNA-seq data from individuals with COVID-19, gene expression matrixes were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and processed in the R programming environment. Transcripts per million (TPM) values were transformed using log (TPM + 1) for expression comparison. Box plots were generated using the ggplot2 package, with statistical significance calculated using the stat_compare_means function (t-test)52. The ggpubr package was then used for correlation analyses53. ChIP–seq data were downloaded from the GEO database in SRA format and converted to FASTQ format in the Linux system with the Conda environment using parallel-fastq-dump software. After quality control, the cleaned files were then aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm10) using bowtie2, generating alignment results in SAM format.

The alignment files were further converted to BAM format using samtools. MACS2 software was then used to perform peak calling and identify potential binding regions in the genome. The resulting files from MACS2 were converted into BigWig format using the bedGraphToBigWig tool. IGV software was used for visualization.

scRNA-seq, clustering and analysis