A Faroese perspective on decoding life for sustainable use of nature and protection of biodiversity

Background

The Faroe Islands and all nations in the world live from nature. Mankind gets its food and raw materials from nature, directly or indirectly. We are now affecting the Earth so heavily and fundamentally that it is proposed to call the present time the Anthropocene—the geological epoch of human influence1.

A well-functioning nature is dependent on healthy ecosystems, which again are intimately linked with biodiversity. The term “biodiversity” includes the full set of all life forms, their variations and functions, and their community structures in the different habitats and ecosystems2. The total biodiversity is a composite of several “sub”-diversities, and among them, genetic diversity (additionally, and subject to the definition of choice, diversity in species, ecosystems, functions, and evolution are often included)2,3. It may well be argued that genetic diversity is the foundation for each of the other “sub”-diversities, and thereby also the total biodiversity. Biodiversity is central to maintaining ecosystems both locally and globally. However, many species, ecosystems, and even global biodiversity are today threatened by overexploitation, fragmentation of nature, loss of habitats, invasive species, and climate change4. Thus, all aspects of conservation, like the protection of species and their genetic diversity, and the protection of the areas and resources that the species depend on, need to be considered to preserve biodiversity, ecosystems and nature as a whole, and at the same time achieve sustainable exploitation to ensure that humans can live in a healthy world in the future2.

It is of utmost importance that we, as the main caretakers of the Earth, have awareness and appreciation of the biodiversity and the existing genetic diversity. Within each single species and within each single individual, the material of inheritance, the genome, is the basis and the main frame for the present diversity and carrying the diversity forward to future generations. It is also recognised that genetic diversity within a species is pivotal for adaptation in a changing world, which is even more important in times of climate change. Thus, knowing the genome sequences from as many species as possible is central to the understanding and knowledge of the full span of biodiversity. With the strong influence that humans have on the ecosystems and the Earth, we will only be able to maintain diversity and exploit it in a sustainable way by having relevant knowledge about diversity. It is difficult or impossible to take unknown or undetected species into consideration in a management plan or to make proper management plans for species, an ecosystem, or a geographical area when relevant and significant biological knowledge, including genetic information, is not available. The sustainable utilisation and management of biological resources require a determined effort (1) to establish current baseline (i.e., number of subpopulations, (sub)population sizes, geographical distribution, effective population size, etc.) for the many species where we have significant lack of knowledge, and (2) to monitor future changes of biodiversity in diverse environments. This is especially important in the view of the human inclination to the “shifting baseline syndrome” (e.g., refs. 5,6). Furthermore, the national definitions of the baseline to use in each case can be much impacted by stakeholders’ views, and political and technical decisions7. Intriguingly, the current population genomic status also gives the possibility of inferring parts of the otherwise undocumented population history in the past8,9,10,11, which can help in establishing different historical baselines.

We should be fully aware that we presently do not know all species, as new species are discovered every year, even in well-explored areas like Europe12. The marine environments are likely to hide many unknown species13. Furthermore, we have limited biological knowledge of many of the species we do know, even among species that are commercially exploited, e.g., their full geographical distribution, subpopulations, population dynamics, interactions with other species, the influences of climate change or human harvesting, etc.

In international policy, the terms “sustainability” and “biodiversity” became much more frequently used after the UN report “Our Common Future” from 198714 and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) from 199215. Article 1 of CBD states that “The objectives … are… the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components and equitable sharing of benefits arising out of utilization of genetic resources.”15. The balance of conservation and sustainable use of nature is repeated in several of the subsequent articles of CBD. All parties of the CBD, including the Faroe Islands (through the Kingdom of Denmark), commit to these objectives. CBD is the basis for additional international agreements and protocols. The Faroe Islands have committed to some of these, like the UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development and its Sustainability Development Goals (SDG)16,17, but not to others, like the Nagoya protocol, the Aarhus convention, and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Not being a member of the EU (despite that Denmark is a member), Faroe Islands are also less restrained by EU regulations and agreements.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Diversity Framework adopted in December 2022, better known as UN CBD Conference of Parties 15 (COP15)18, underlined the importance of genetics and genetic diversity in biodiversity and sustainability, as reflected in their direct mentioning in two of the four overarching goals:

-

The genetic diversity within populations of wild and domesticated species is maintained, safeguarding their adaptive potential.

-

The monetary and non-monetary benefits for the utilization of genetic resources … are shared fairly and equitably.

This is also repeated in some of the corresponding 23 targets for the Kunming-Montreal framework:

-

Target 4: Ensure urgent management actions, to halt human induced extinction of known threatened species and for the recovery and conservation of species, in particular threatened species, to significantly reduce extinction risk, as well as to maintain and restore the genetic diversity within and between populations of native, wild and domesticated species…

-

Target 13: Take effective legal, policy, administrative and capacity-building measures at all levels, as appropriate, to ensure the fair and equitable sharing of benefits that arise from the utilization of genetic resources…

-

Target 21: Ensure that the best available data, information and knowledge (this undoubtedly include genetic data, information and knowledge; authors’ comment), are accessible to decision makers, practitioners and the public to guide effective and equitable governance, integrated and participatory management of biodiversity, and to strengthen communication, awareness-raising, education, monitoring, research and knowledge management…

Indirectly, having the species’ genome assemblies and knowing the genetic diversities will wholeheartedly support the other overarching goals and targets for the Kunming-Montreal framework that involve sustainability and sustainable management, and further the integration of biodiversity into policies, planning and regulations, including the protection of species, habitats, ecosystems and areas, etc.19,20. The four overarching goals and the 23 more specified targets can be seen as an elaboration and specification from previous international agreements and protocols. We will here have a main focus on how genomes and the knowledge of genetic diversity can help us protect biodiversity and maintain sustainability to reach different aims and potentials.

Genome Atlas of Faroese Ecology (Gen@FarE)

Knowledge of the full genome of each species and the genetic diversity within each species provide powerful tools to monitor biodiversity and, through that, manage and preserve it2,21. This knowledge can be used in different ways and for different purposes. On the very practical and applied side, management of commercially exploited resources and protection of species and/or habitats can be much improved by such tools, e.g., determining subpopulations that should be independently managed for commercial bioresources or defining the habitat for elusive species by the DNA traces they leave behind. It will also give us better tools to survey the environment, whether it is for invasive species or population estimates. Equally important, such knowledge is valuable for understanding the diversity of life in all its aspects and functions, and it will undoubtedly initiate further questions and give new avenues to explore (see section “Incidental insights”). Above all, this will help us in protecting and maintaining a healthy Earth for mankind and all its fellow beings.

National and regional initiatives are taking place both in Europe and globally by people and institutions recognising the need for, and the potential of, genomic knowledge22,23,24,25,26. This is a highly international task, where many levels need to contribute and collaborate, from local communities and indigenous peoples to nations. We all, as individuals, as industry, as society, as nations, have responsibility for the future of the Earth and its nature, and the politicians and governments must set the frames so this can become possible to achieve. Realising the urgency and need to protect biodiversity, and that genomics and genetics are essential tools in achieving this purpose, more than 700 European scientists, some of the present authors among them27, have gone together to form the European Reference Genome Atlas project (ERGA)22,28,29,30 as a collaborative and interdisciplinary network. Also, small nations, like the Faroe Islands (1400 km2 and 54,000 inhabitants), should contribute to this effort, partly as a global and moral obligation, and partly to ensure sustainability in its exploitation of biological resources in accordance with CBD15. Utilising the ERGA network and its dedication to a decentralised and equitable biodiversity genomics30, the present authors have initiated the Genome Atlas of Faroese Ecology (Gen@FarE), and we participate in the ERGA Pilot project30. Although a small nation, the Faroe Islands have a sizable economic zone (274,000 km2) in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean, and it has large fisheries activity. Thereby the nation has a particular responsibility towards maritime matters. The authors represent Faroese institutions with responsibilities for education, research, monitoring, and dissemination of knowledge within Faroese and North Atlantic biology and biodiversity, and advising the authorities about stock management and nature in general. We jointly see the advantage of increased genomic and genetic knowledge for protecting biodiversity and achieving sustainability in the region.

The Genome Atlas of Faroese Ecology has three major long-term aims:

-

To establish high-quality genomes of all eukaryotic species in the Faroe Islands and Faroese waters.

-

To establish population genetics for all species that are commercially exploited or are of ecological interest.

-

To establish an information databank for all Faroese species, combined with a citizen science registration database, making it possible for the public to participate in acquiring and maintaining the overview of Faroese species in both terrestrial and marine areas.

We expect that it will take many years, maybe decades, before having high-quality genome assemblies from all Faroese species, despite the expected technological advances and the consorted accumulation of relevant genomes and data from other countries. We are aware that other projects, like the Earth BioGenome Project23,31, may have more optimistic views on how fast such an aim will be achieved, but a large upscaling of capacities is needed23,31. The urgency of protection and maintaining biodiversity and ensuring sustainability in the harvesting of nature requires that it is worked on all three aims in parallel.

In the long-term process, there are many other direct and indirect aims, some of which we may not yet be aware of, some that are general, and others that are associated with a particular species. In particular, we would like to point out the close link to biomonitoring using metabarcoding (see section “Biodiversity and conservation”), as the product from the genome assembly efforts will help close the lacks and gaps in reference sequence databases due to the absence of species or genes, or intraspecies variability in marker genes. This is one of the reasons why ERGA and the European node of the International Barcode of Life (iBOL Europe) recently joined forces in the Biodiversity Genomics Europe consortium32.

Biodiversity and conservation

Of course, partly as a consequence of the CBD, each nation has an added moral responsibility for diversity existing only (or mainly) within their national borders and maritime economic zone. Although there are few known endemic species in the Faroe Islands, it has its share of bird diversity with the world’s largest colony of European storm petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus), one of the few last remains of (claimed) wild-type rock pigeon (Columba livia), and recognised subspecies of several other birds (European starling, Sturnus vulgaris faroensis; Eurasian wren, Troglodytes troglodytes borealis; common eider, Somateria mollissima faeroeensis, etc.) (see ref. 33 for more information). However, we will in this paper not focus on this particular part of biodiversity.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List status is often an important part of decisions for “what to do” and “how to do” in the conservation and protection of species31. The assessment of the Red List status is based on population size, population trends and some other parameters34, some of which are not always easy to assess for different reasons. One could imagine the inclusion of genetic diversity status into this assessment, both as an independent parameter and as an indirect parameter for assessing effective population size10,19,20,35. It is well known that low effective population size increases the rate of homozygosity. Runs of homozygosity have been used for estimating historical bottlenecks for certain species11,36,37 as they are recognisable long after a potential expansion of the population following a bottleneck. It might be possible to take similar models into use for practical conservation and protection purposes, like the national and regional Red Lists. However, one study found no direct correlation between the Red List status and runs of homozygosity for a limited set of mammals37. Another recent study also showed poor correlations between two proxy-indicators for genetic diversity and Red List status19. In contrast, other studies (e.g., ref. 38) found a better correlation between degree of homozygosity and Red List status. The lack of correlations could have several explanations, as hinted at in ref. 37, like (1) the populations have not reached sufficiently low level to erode genetic variation in the individuals; (2) when the decline is rapid (as it is in many cases) and without any particular genetic selection pressure, the relative degree of heterozygosity is maintained for quite a while, and runs of homozygosity only become evidently apparent after some generations at low population size, and (3) species with vastly different population sizes may end up in the same or different Red List categories of threat dependent on other parameters (see ref. 34 for Red List criteria).

Next-generation sequencing and, in particular, third-generation sequencing have shown that structural genetic variants are more common than previously thought. In some cases, structural variants are probably decisive for ecological adaptation and migration39,40 (see also section “Sustainability and commercial exploitation”), and in other cases, they influence morphotypes and behaviour39,41,42,43. In the Palaearctic wader, ruff (Philomachus pugnax), an inverted chromosomal region controls three male phenotypes affecting behaviour, body size and plumage colour41,42, although not creating a reproductive barrier. The redpoll finch complex is presently regarded as three species (hoary redpoll, Acanthis hornemanni; common redpoll, Acanthis flammea; lesser redpoll, Acanthis cabaret), but they have considerable overlap in geographical distribution and may hybridise to some degree. Again, these three redpoll phenotypes are controlled by a large inversion43. In principle, a recent inversion does not necessarily change the frequency and identity of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are located in the inverted area, unless the genes and other genetic elements in the inverted area are under some kind of selective pressure. Certainly, the most comprehensive way to detect new or previously unknown SNPs and structural variants is by genome sequencing. Even so, short-read sequencing, a powerful approach to detect both known and previously unknown SNPs, may have problems in detecting the inversion itself, especially when low-coverage sequencing is used. Long-read sequencing, like nanopore (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) or Single Molecule Real Time (SMRT; PacBio) sequencing are presently the ultimate tools for this purpose, and both are used by ERGA groups to achieve high-quality genome assemblies. Thus, both for population genetics and for basic biological research in all kinds of species, it is a great advantage to establish a high-quality species-specific reference genome and, from this, develop genomic tools in investigating a particular species and its subpopulations.

Since the development of large-scale and sensitive DNA sequencing technologies, the use of environmental DNA (eDNA) and metabarcoding have gained popularity for different purposes, including the assessment of biodiversity44,45,46,47,48,49, estimates of spatial distribution50,51, invasive species detection52,53, and predator-prey interactions49. These methods are likely to be valuable tools in future assessments of biodiversity trends and changes in relation to anthropogenic pressures. In the Faroe Islands, eDNA programmes for monitoring marine biodiversity have been ongoing since 2018 onwards. These approaches have already increased the number of species registered in the Faroese marine environment (Salter et al., submitted). However, these methods rely on the exactness and completeness of the relevant genetic databases, but also taxonomic expertise for the correct registration of species. We know that the databases are far from complete, although there has been a great effort in different barcoding projects, like the Barcode of Life54 and iBOL Europe55. Thus, assembling high-quality genomes and eDNA metabarcoding are complementary methods, and in particular, the genome sequencing of more species will improve the outcomes of eDNA and metabarcoding approaches.

Another factor that may influence both the completeness and the exactness of the databases are cryptic species, i.e., that two or more distinct species are classified as a single species due to their morphological similarities56. Cryptic species are found within all organismal groups57, and is a different concept than subspecies, where morphological criteria can distinguish between (usually geographic) subpopulations. Still, both concepts can lead to the definition of new species. It was only a few years ago that a well-known animal like the giraffe was divided into four species58 and approximately every year subspecies of birds are split out as unique species, or the other way around (e.g., ref. 59). Genome sequencing is probably the most definitive way to sort out cryptic species (or if a subspecies should be split out as a distinct species), although there is no specific limit of genetic differences that defines the transition from one species to another. In any case, having high-quality genome assemblies available from as many species as possible will improve the genetic databases and their practical use for many purposes, including the ability to describe new species, whether based on previously known subspecies or cryptic species.

Sustainability and commercial exploitation

The sustainability of harvesting (presently) abundant species is often not thought of as a part of a conservation process or mechanism. We here briefly remind about the extinction of the once abundant passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius)60 and the collapses in the stocks of Northwest Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua)61 and Northeast Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus)62, indicating that such considerations should be taken. The Faroe Islands is a maritime nation, where fisheries are of crucial importance. Thus, UN SDG 14 Life Below Water (“Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”) is particularly relevant. Fishing is considered the main threat to the Faroese marine ecosystem63. In the Faroe Islands, and elsewhere, certain fish species are commercially harvested despite that the knowledge of their biology is limited. This is perhaps most evident for species where industrial fisheries have developed during the last few decades. History has repeatedly shown that it is possible to overexploit fish stocks, resulting in a collapse from which it may take decades to recover64. It has been estimated that one-third of fish stocks are presently overfished65. Also, for commercially exploited species it is an advantage—and need—of maintaining subpopulations and genetic diversity in a changing world. Genome sequencing is a crucial tool to achieve the conclusive assessment of subpopulations and population structure.

For some fish species, it has been known for a long time that the population consists of several stocks, i.e., subpopulations that breed independently. e.g., Atlantic herring consists of stocks that spawn in different areas of the North Sea and the North Atlantic, with some stocks spawning in the spring and others in the autumn. Still, herring gather in large schools migrating across the Northeast Atlantic, and the different stocks often mix in such schools. It is important to estimate the fraction of each stock in catches from such mixed schools to avoid overexploitation of certain stocks. Traditionally, the assessment of stock mixing in catches has been based on phenotypic properties (morphology, otoliths), although genetic tools have entered some fisheries. Phenotypic analysis is time-consuming and not necessarily exact. Based on recent and better genome assemblies66,67, it has been possible to refine genetic markers in the herring genome, improving the potential in distinguishing between different stocks of herring in the Northeast Atlantic68, which are exposed to one of the world’s largest fisheries. Many of the genetic markers are positioned in an area of herring chromosome 12 that is associated with ecological adaptation40,68, and which in some stocks contains an inverted part of the chromosome40. This type of inversion is often called a “supergene” and contains a set of tightly linked genes giving rise to a certain and stable phenotype.

Similarly, Atlantic cod are divided into numerous stocks, some of which are migratory and other are stationary, and with limited gene flow between these stocks, despite some of them spawning in the same area and season. This is (at least partly) associated with certain inverted supergenes39,69,70. Faroese waters have two distinct populations of cod, one at the Faroe Plateau and one at the Faroe Bank. The latter is fast-growing, large-sized fish71 and locally known for its superior quality. We are confident that the Faroe Bank phenotype is strongly associated with certain, as yet unknown, genetic properties. By being able to genetically separate Faroe Bank cod from other local cod stocks, we would get a valuable tool in the search for the feeding grounds of the young Faroe Bank cod (age 0.5 to 3 years), which are not known today, although it is presumed they are local on the Faroe Bank72. Additionally, identifying the genetic properties associated with rapid growth and high quality may help in the efforts to make farmed cod a commercial reality.

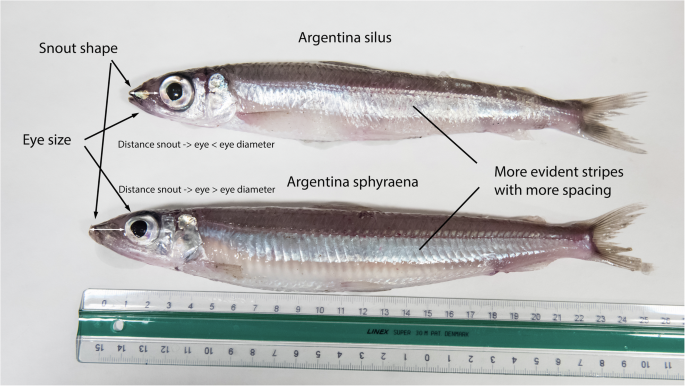

The greater silver smelt (Argentina silus) is a relatively new, but, as yet, limited target for commercial fisheries, with an average annual catch of around 50 000 tonnes in the Northeast Atlantic, much of this in Faroese waters71,73. It is commonly found at depths of 150–1400 m and it is long-lived and slow-growing74. Species with these characteristics are vulnerable to overexploitation, because the longer the time to reach maturity, the longer it takes to increase the population after a potential collapse. The stock structure is unknown (ref. 73 with stock annex). The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (better known by its abbreviation, ICES) has divided the greater silver smelt into four assessment units despite the lack of knowledge of separate biological populations73. Spawning may occur in several seasons or in prolonged periods of the year and spread around vast areas74. These were the major reasons why the greater silver smelt was suggested as a Faroese ERGA pilot species. Through the ERGA efforts, its genome assembly became available in the spring 2023 (Table 1; GenBank GCA_951799395). This genome assembly is the first available genome from the order Argentiniformes. The genome will give us insight into the biology of the species and help to develop population genetic markers (which we presently are doing), making it possible to assess the population substructure in the North Atlantic, and thereby improve the management of this species. Additionally, we are also working on the genome assembly of a sister species, the lesser silver smelt (a.k.a. lesser argentine; Argentina sphyraena). The two species are morphologically rather similar (Fig. 1) and have overlapping geographical distributions, and there is a risk of mixed catches. With their genomes available, genetic tools can be developed to easily assess the presence of one or the other or both species, even in industrial fish products in the supermarket (e.g., ref. 75).

They have quite similar appearances and have overlapping geographical distributions. The shown individuals are (lower) adult lesser silver smelt (max. length 35 cm) and (upper) subadult greater silver smelt (max. length 70 cm). The two individuals were caught in the same 1 h trawl haul (survey cruise with RV Jákup Sverri) at 200–220 m depth (decimal position 61.60 N, 7.45 W) on the 9th of August 2023. Greater silver smelt is also known as greater argentine, Atlantic argentine or herring smelt. Lesser silver smelt is also known as lesser argentine. Photo and labelling by SOM.

The lesser sandeel (Ammodytes marinus) is another Faroese ERGA pilot species. The ERGA efforts made its genome assembly available in the spring 2023 (Table 1; GenBank GCA_949987685). The lesser sandeel is one of several species collectively known as sandeels or sand lances. These species are important prey for birds, larger fishes and marine mammals, and they are an important link between primary production and higher trophic levels76,77,78. In this recognition, the UK government prohibited fishing of sandeels within English waters of the North Sea from 26th March 202479. The sandeels have typical seasonal behaviours and burrow into sandy sea bottom during much of the winter. They are little used for human food but are industrially fished, especially by countries around the North Sea. The total annual catches have varied between 100,000 and 1 million tonnes80. The intense fishery may influence seabirds at different stages of life81,82,83, and thereby contribute to the observed decreases in seabird populations84,85. It is poorly understood whether the sandeel populations in the different regions of the North Sea and the Northeast Atlantic are genetically distinct populations and to which degree there is gene flow from one region to another86. Knowing the genome sequence of the lesser sandeel (and for the related species) would be highly valuable for developing genetic panels for such investigations, and we are presently working to establish its population genetics in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean. Better knowledge of sandeel subpopulations and their genetic interconnections would improve the basis for quota determination in different management areas. At the time the ERGA pilot project was initiated, there were no publicly available genome assemblies from the taxonomic order Uranoscopiformes, to which the sandeels belong. During 2022 and 2023, genome assemblies from four species in this order became available, including the mentioned genome assembly from Ammodytes marinus. These genomes will make it easier to assess whether these species, which are morphologically rather similar and have overlapping geographical distributions, are prone to mixed catches. Even more importantly, the genome assemblies could be a tool in ecological studies, both to improve the knowledge of sandeel biology in general and for investigations of species interactions.

An important aspect in the sustainable exploitation of wild species is to ensure that the population and the potential subpopulations are large enough to endure the harvesting pressure—in essence, that the species is maintained at a sufficiently sized population within its natural fluctuations. Moreover, there are a number of species for which commercial interests have more or less concrete wishes for developing new fisheries or are in the early phases of exploitation. The targeted species may range from deep-water fish to zooplankton (like krill or Calanus spp.), and we know little about how this will affect both the species itself and interacting species. Acquiring adequate knowledge and overview of species that are commercially exploited or suggested for commercial exploitation, should be common sense. High-quality genome assemblies are likely the best basis to acquire such knowledge, as it can later be diversified into separate and specialised sub-tools for specific questions and investigations. One such question is how intensive fisheries are influencing the genetic future of the species. Intensive fisheries may give selection pressures influencing traits such as size-at-age and age-at-maturation87,88, but we know less if and how this influences the ecosystem on small89 or large scale, or the long-term trajectories of genetic diversity.

Interaction between species

Species interact in all kinds of ways: in food webs being prey and predator, by symbiosis and parasitism, by living permanently or temporarily in the mixed groups, by competing or collaborating, etc. DNA investigations may reveal much about such species interactions and ecosystem services.

Public attention is much directed towards “visible” species, but for many purposes, “invisible” species may sometimes have large consequences, whether they have a lifestyle that hides them from the human eye (night activity, under water, in soil), or they, in fact, are so small that they really are invisible to the naked human eye. We will mention a few more or less local examples, two of which concern “invisible” species, where genomic knowledge could be translated into practical tools or managemental choices and decisions.

Planktonic algae (together with bacteria and viruses) form the bio-basis of the entire marine ecosystem on which the Faroese economy relies. Many algae are difficult to distinguish morphologically, and DNA has become an important tool for routine algal biodiversity monitoring. However, there are taxonomic uncertainties, and probably many cryptic species and much unknown intraspecies genetic variations among algae90. Thus, there are still many gaps for algae in the sequence databases. This also includes toxin-producing algae91,92,93, which are of interest to people collecting mussels, the shellfish industry and fish aquaculture. Furthermore, the combined influence of climate change and the unintended transport and release of algae and other marine species, especially by ballast water or by attaching to the hull of ships, is likely to be an increasing problem in northern regions (e.g., ref. 94). The ability to detect invasive species, including unexpected invasive species, will increase as the genomic databases become more complete.

Invasive species are generally unwanted because they may affect the local native species and the ecosystem in adverse ways. Island biodiversity is particularly vulnerable to the impact of invasive alien species as is recognised in Kunming-Montreal target 6 for stemming biodiversity loss. As elsewhere in the world, rats95 and mice96,97 are invasive species also in the Faroe Islands. There is a particular worry that rats will spread to the few rat-free islands, especially as the rat-free Sandoy was connected to the rat-infected Streymoy by an undersea tunnel in December 2023. However, there are also more subtle invasive species in the Faroes. The New Zealand flatworm (Arthurdendyus triangulatus) was first reported in the Faroe Islands in 1982, possibly introduced from Scotland or New Zealand by soil following imported plants or trees98. The New Zealand flatworm preys on local earthworms, thereby, over time, possibly degrading the quality and the properties of the soil. Although there is some knowledge about genetic variations in the flatworm99, a recent evaluation concluded that there are large gaps in the sequence data from this and related species, making it impossible to assess the reliability of the DNA markers100. Thus, having a genome assembly would be the basis for much better tools to follow the routes of spreading (for example, by eDNA), and possibly also to find potential targets for countermeasures.

There are no native terrestrial mammals in the Faroe Islands. Among typical free-roaming herbivores, only mountain hare (Lepus timidus) and domestic sheep have been deliberately introduced, the former with four animals (from coastal Norway) in 1855, and the latter probably with the first settlers well before year 1000 (and with many subsequent import events). Hunting of hare is a popular tradition, and the registered yield is between 3000 and 9000 hares/year (Eyðfinn Magnussen, pers. comm.), which is extremely high considering an area of 1400 km2. One may imagine that hare and sheep could compete for food resources, given the high density of both species. This could be possible to investigate using different genetic tools, provided that the necessary genetic data are available for the local plants. Another interesting question is microevolution in hare, as all the local populations are founded from the first few animals introduced nearly 170 years ago. This includes the genetics behind the grey winter fur of Faroese hare. Grey winter fur is also known from parts of coastal southern Norway, and we would suppose that the grey winter furs of Faroese and local Norwegian hares have the same genetic background. Hypothetically, the grey winter fur could be caused by a recessive allele in the introduced animals, and it probably became fixed in the population as the white hares were more easily shot during the late fall hunting in (usually) snow-less conditions (hunting of hares started only a few years after the introduction, and the first legislation on hare-hunting is from 1881).

Interactions with and dissemination to the society

The third main aim of Gen@FarE is to establish an information databank in Faroese, covering all Faroese species and nature types. It is a scholarly obligation to inform the public in various ways, like educational and outreach programmes, museum exhibitions and events, popular science presentations, etc. Museums and public collections have a long tradition in natural history and have been highly important in disseminating knowledge and information to society, whether we consider school classes, single individuals or the authorities. At the same time, many are interested in different aspects of biodiversity, and this is reflected in citizen science projects like iNaturalist101 and eBird102. More than 1.5 million observation lists (usually with several species and many individuals of each species in each list) were submitted to eBird during February 2023, and more than 1.3 million single observations were added to iNaturalist in the same period. When the scale of the collected data is big enough, the geographical and seasonal distribution and abundance of species become apparent and, over time, disclose population trends, as noticeably illustrated by eBird103,104,105. Additionally, and possibly undervalued, highly skilled non-professionals and laypersons contribute considerably to the identification and description of new species12, and even more so to the geographical distribution of species106. Of course, citizen science data may not rise to the same standards as professionally collected data107, but the shortcomings can be more or less counteracted by diverse measures108,109,110,111, and time and again, citizen science data have shown their value as indicated by the references above12,103,104,105,106.

Our Nordic neighbours have organised national searchable public biological information banks interlinked with the possibility of registration of citizen science observations (Sweden with Artdatabanken and Artportalen112,113; Norway with Artsdatabanken and Artsobservasjoner114,115; and Denmark with Arter.dk116). Both the national and international citizen science initiatives mentioned above have identification tools, either integrated into the website or as free-standing mobile telephone apps117,118,119,120, which significantly lowers the threshold for contributing to citizen science.

Consistent with article 13a Public Education and Awareness in CBD (“The Contracting Parties shall promote and encourage understanding of the importance of, and the measures required for, the conservation of biological diversity, as well as its propagation through media, and the inclusion of these topics in educational programmes”) and target 21 in the Kunming-Montreal agreement (see “Background” section), we believe that the ability to easily access the established knowledge on species and the possibility of the public in contributing to the knowledge building, will increase the interest in the species and in nature values in general. The combined data from organised research and citizen science will, over time, indicate abundance and trends and point out geographical areas with particular values of nature (e.g., rare type of biological or geological landscape at national or international level; high biodiversity; habitat of rare or threatened species, etc.). This information will help in management decisions of various kinds, like protection of species, development of area plans, conservation of smaller or larger areas, etc. It will increase the transparency and the interactions between the scientists, the authorities, the politicians, and the public for many aspects of the preservation of species, management and conservation of areas, and management and sustainable exploitation of species.

Incidental insights

As genomes from more and more species are sequenced, it is evident that we will learn much about each single species. However, a single species does not exist without being connected to other species, not only in their habitats, in their ecosystems, and in their food webs, but they are also genetically connected to other species through evolution and the process of speciation. As more genome assemblies become available, we will undoubtedly understand more about the genetic processes, physiological processes, the immune system, protection against pathogens, and lots of other areas that give us deeper insight into life and basic processes of life23,121, and some of which may find applications in the future for improving our food production, and give new medical treatments, new materials, more eco-friendly industrial processes, etc. We can safely assume that there will be continued advancement in methods, instruments, and bioinformatics, which will give us new and efficient tools that can also be applied to various questions and purposes. In short, we will have more insight into being humans, our own biology and genetics, and similarly for our fellow beings, and understand more about taking care of nature and the Earth, which ultimately is to take care of ourselves.

Responses