A framework for just seascape restoration

Introduction

The complex relationship between humans and coastal marine ecosystems has been sustained since time immemorial, with these ecosystems – including coral reefs, mangrove forests, seagrass beds, oyster reefs, and salt marshes – providing sustenance, livelihoods, and cultural value worldwide1,2. These vital ecosystems are often connected by biological, physical, and chemical processes3, including the movement and dispersal of organisms4, and are often referred to as seascapes. Seascapes are “large, multiple-use marine areas, defined scientifically and strategically, in which government authorities, private organizations, and other stakeholders cooperate to conserve the diversity and abundance of marine life and promote human well-being”5. In this perspective, we define a seascape as a connected, spatially heterogeneous area of coastal marine environment6 consisting of highly interlinked human and ecological elements7, regardless of scale.

With billions of people reliant on the goods and services provided by seascape ecosystems, they play a pivotal role in biodiversity and human wellbeing8. However, escalating and compounding anthropogenic threats such as climate change, habitat destruction, and pollution are degrading the resilience and functionality of these habitats9,10. Major challenges facing seascapes globally include coral reef degradation11, coastal eutrophication12, hypoxia13, wetland reclamation14, and the increasing presence of heavy metals15 and pollutants due to coastal exploitation16. Such losses have amplified the need for effective seascape restoration to safeguard both environmental and socio-economic health17.

Passive conservation methods, such as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and no-take zones, are often used to counteract or prevent seascape degradation18. However, these passive methods assume that a region will be able to recover by natural processes without human intervention19. Unfortunately, the complexity of the challenges faced by seascapes is often inadequately addressed by passive conservation approaches, which may neglect the nuances of multi-habitat interactions20, the cumulative impacts of various threats21, and the diverse perspectives of resource users -individuals or groups who depend on natural ecosystems for their livelihoods, cultural practices, or recreational activities22, potentially leading to suboptimal outcomes23. For instance, the establishment of MPAs as a single solution to maintain or enhance biodiversity often fails to include effective management and enforcement of the MPA, consequently leading to increased poaching and possible overharvesting24. Additionally, rising temperatures have caused some marine species to migrate toward higher latitudes, potentially moving the range of certain protected species beyond the fixed boundaries of MPAs, thereby reducing their effectiveness25,26. Active restoration strategies – the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed, with the aim of re-establishing its ecological and social functionality, biodiversity, and resilience – have been employed to supplement habitat protection. Many of these active restoration efforts have become important tools to help replenish seascape ecosystems including coral reefs27, mangrove forests28, and seagrass beds29.

Although active restoration efforts can be utilized as an alternative restoration option or to supplement MPAs, they can bear traits of “parachute science” or top-down approaches which prevent them from meeting the needs of the local ecology and community30,31. Evolving beyond these methods to embrace a holistic and just restoration philosophy that integrates ecological, social, and economic considerations is a means to center community needs and knowledge in restoration practices. Evidence of the effectiveness of such integrative approaches is mounting, with integrative restoration strategies demonstrating the potential for enhanced ecosystem resilience and recovery in seascape ecosystems20,32. These strategies recognize the importance of socio-ecological priorities, including the human dimensions (governance, social, political, cultural, and economic) of coastal ecosystems33, and the role of communities in shaping and sustaining restoration efforts34,35,36. For instance, community-based management strategies in Trinidad and Tobago have effectively built networks crucial for coping with extreme climate events, thereby enhancing the adaptive capacity and resilience of local social-ecological systems37.

The importance of just community engagement in the restoration process has been noted in land38, watershed39, coastal40, and marine41 restoration efforts. Here, we refer to just seascape restoration as restoration practices that aim to repair the socio-ecological functions of marine ecosystems while ensuring fairness and inclusivity in decision-making and implementation. This approach integrates restoration efforts that not only enhance ecological resilience but also address the socio-economic and cultural needs of local communities, emphasizing equitable participation and benefits across all individuals involved in, or impacted by, the restoration process20,42. A technical review on the state of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLC) detailed their vital role as custodians fof natural landscapes and emphasized the necessity of including them in the development of management and restoration projects to achieve global conservation goals43. When communities are justly engaged in every stage of planning, including problem assessment, decision-making, and implementation, including whether restoration is an appropriate solution, there is a higher probability of success37,44,45. Global conservation policies, such as the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), have acknowledged the importance of just community engagement in conservation, including benefit sharing, the need for appropriate recognition and inclusion of Indigenous peoples and local communities, local livelihoods, co-development of projects, and participatory and equitable management46. Hein et al. conducted key-informant interviews to characterize local resource users’ perceptions of coral reef restoration47. Respondents reported disconnects between the restoration efforts and the local community as the second most significant limitation to coral reef restoration, with the most significant being lack of capacity. This disconnect was attributed to a lack of partnerships and communication with the public. These same respondents also categorized the socio-cultural benefits of restoration as outweighing all other benefits, including ecological benefits of restoration.

Justly centering communities is universally applicable across all types of ecological restoration. However, its significance can be amplified in seascape restoration due to the intricacies of working within varied ecological systems and sociopolitical frameworks that are present in many coastal and island communities. These projects necessitate the involvement of diverse stakeholder groups, each potentially governed by distinct traditional, legal, and social systems48,49. For instance, in the Solomon Islands, women play a significant role in small-scale fisheries, yet they are often excluded from decision-making. This governance gap can undermine local marine management efforts, as women’s needs and knowledge are overlooked, occasionally resulting in non-compliance with local regulations50. In Fiji, iTaukei communities manage mangrove ecosystems through traditional governance practices, such as the implementation of Tabu areas, where resource harvesting is prohibited for set periods to ensure sustainable use. These traditional methods, combined with local knowledge, support both ecosystem health and community livelihoods, emphasizing the importance of integrating tribal and local governance in resource management51.

Here, we build upon current coastal and marine ecosystem restoration guidelines40,52,53 to develop a framework with actionable recommendations for scientists, practitioners, and managers to conduct just seascape restoration by suggesting steps to consider during the planning and implementation of restoration initiatives. Existing restoration guidelines recognize the importance of engaging communities in restoration, but they do not explicitly detail how to do so justly. Additionally, guidelines are geared toward restoration practitioners and managers, not scientists who may have no training in community engagement. In addition to restoration guidelines, we draw on socio-ecological and ecological restoration literature to establish a framework for just seascape restoration54,55,56,57,58,59. While we focus on seascape restoration, these suggestions can be applied to other ecosystems and scales.

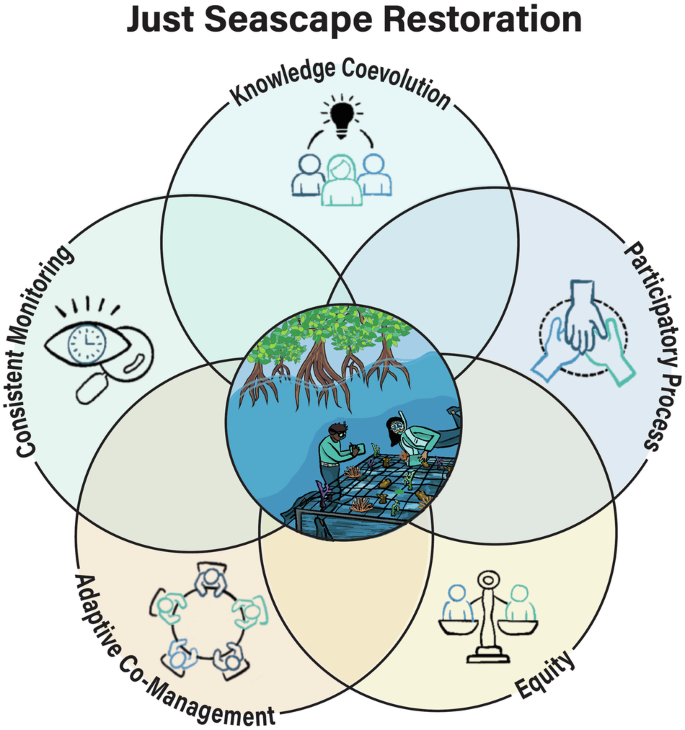

To develop our recommendations, we conducted a broad review of primary and gray literature related to ecological restoration, management, and social-ecological systems. Our review encompassed academic journal articles, reports from government and non-governmental organizations, as well as case studies from community-based restoration initiatives. We synthesized this information to pull out key themes that point to successful and just ecosystem restoration, while also identifying common challenges and failures that hindered equitable outcomes, allowing us to develop more comprehensive recommendations. Key resources used to develop our recommendations are highlighted in Table 1. Our framework is organized into five concepts: knowledge coevolution, adaptive co-management, equity, participatory process, and consistent monitoring (Fig. 1, Table 1). Through this perspective piece and framework, we hope to highlight the importance of community-partnership in restoration, provide clear steps scientists and practitioners can take to engage in just restoration initiatives, and inspire the restoration community to give primary consideration to the communities in which they work.

All concepts are inter-connected and equally important in achieving restoration practices that are lasting and equitable.

Recommendations for just seascape restoration

Knowledge coevolution

Knowledge coevolution is a key component of successful seascape restoration, as it ensures all stakeholders have equal opportunity to shape conservation strategies. Knowledge coevolution builds upon the concept of knowledge co-production by emphasizing the parallel advancement and mutual respect of both Traditional Knowledge (TK) and Western Science (WS) systems, without the intent to alter or merge one with the other60. It is a process that fosters the independent progression of each knowledge system, thereby reinforcing Indigenous stakeholders’ capacity for self-determination in the governance of their communities and natural resources. This approach not only generates data that is intrinsically meaningful for Indigenous decision-making but also respects and preserves the integrity of culturally embedded worldviews and learning practices, including a recognition that knowledge is borrowed rather than created31, thereby contributing to the decolonization of research structures and norms35,61.

For instance, in Pacific Island countries, conservation efforts, tourism economy, and livelihoods are deeply interconnected31,62,63. Traditional Knowledge, passed down through generations, such as traditional medicine, sustainable fishing techniques like the bul (a customary fishing moratorium64, names of species, and wildlife behavior, was originally taught for survival65,66. Today, this knowledge not only continues to ensure sustainable resource management but also plays a key role in attracting ecotourism and raising cultural awareness. In Palau, for example, ecotourism initiatives incorporate this Traditional Knowledge into visitor education programs, fostering a deeper understanding of both the ecological and cultural significance of conservation practices67. When combined with Western Scientific knowledge – such as using data from biodiversity assessments and marine monitoring – this Traditional Knowledge offers a comprehensive and adaptive approach to understanding and managing local ecosystems. This integration enhances both restoration and conservation efforts by ensuring that local cultural practices and scientific insights work in tandem to sustain biodiversity and community livelihoods31,68.

Employing a knowledge coevolution framework is fundamental in just seascape restoration. This framework fosters a mutually beneficial relationship where scientists, local groups, communities, tribal governments, relevant organizations, and other resource users work collaboratively to develop restoration projects35,57. Often, restoration efforts are designed and implemented without meaningful input from the local community69,70, which can result in unsustainable and ill-informed projects that may inadvertently perpetuate environmental injustice71,72,73,74. For instance, a study examining community-based restoration projects across rural and indigenous communities in Mexico found that less than 6% of restoration efforts reported incorporating local communities in the planning process. This lack of engagement often resulted in projects that were constrained by funding and performed for only the short term, undermining the sustainability of these initiatives69. Additionally, in urban restoration projects in Aotearoa, New Zealand, a failure to initially include Indigenous Māori communities led to power imbalances and limited ecological and cultural benefits. By contrast, projects that engaged Māori communities from the outset and acknowledged the historical connections to land achieved greater success, demonstrating the critical role of local partnerships in achieving environmental and social justice outcomes70.

The integration of Western Scientific knowledge with Traditional Knowledge has been shown to enhance the success of restoration projects by combining the empirical rigor of WS with the place-based expertise of TK. For example, in coastal restoration projects in Louisiana, a GIS-based method was developed to incorporate TK from local fishing communities alongside geospatial technology and scientific data. This integration resulted in more effective coastal restoration decision-making and project planning by ensuring that local ecological knowledge of marsh degradation and ecosystem dynamics was considered alongside scientific data sets75.

Knowledge coevolution can improve power dynamics and adaptive capacity, more effectively identify areas of need, result in more efficient problem solving, and increase the likelihood of long-term success58,69,70,76,77. An important aspect in knowledge coevolution is the equal priority given to local-ecological knowledge, including TK, in issue identification, planning, and implementation. WS is generally used to evaluate the validity of restoration and management, causing local ecological knowledge systems to be dismissed or discounted78,79,80. By excluding diverse ways of knowing, we limit the potential impact of restoration. Pairing WS insights and TK allows restoration to be equitable and sustainable81,82.

The “Two-Eyed Seeing” approach or Etuaptmumk, described by Elder Dr. Albert Marshall as “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing…and learning to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all,” can be utilized by practitioners to engage in knowledge coevolution79,83,84,85. This approach has been successfully applied in several ecosystem restoration projects, such as those in Hawaiian forests, where both Indigenous Hawaiian knowledge and WS were used to restore native tree species and improve water management systems86. Scientists, practitioners, and managers can use their power and privilege to act as facilitators and community builders by connecting holders of local-ecological knowledge, resource users, and government organizations to inform official ecosystem management and restoration procedures57. Frequent communication via check-ins and meetings with project members is essential for successful project implementation, and leaders should prioritize open discourse at all levels of planning58,70. Finally, and importantly, flexibility in understanding all perspectives and mutual respect must be employed throughout the entire restoration process to allow the coevolution of knowledge57,69.

Multiple ways of knowing have been increasingly recognized as an important aspect of successful restoration and management and have been implemented in recent projects57,58,87. A technical review on the state of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLC) detailed their vital role as custodians of natural landscapes and emphasized the necessity of including them in the development of management and restoration projects to achieve global conservation goals43. Knowledge coevolution and co-production have been found to improve the management of many species and ecosystems, including the American lobster84, beavers’ role in stream restoration88, and the restoration of Hawaiian forests86.

In seascape restoration, knowledge coevolution is paramount due to the possible unique local and traditional knowledge holders tied to different seascape habitats and the intricate relationships between them. For example, Palau presents a model of stewardship distribution between genders, where men and women are custodians of distinct ecosystems, highlighting the need to engage a diversity of knowledge holders49. This gendered division of ecological stewardship, rooted in cultural norms and practices, necessitates that both groups are consulted and involved in the planning and implementation phases of restoration projects89. Additionally, it is essential to include a diverse range of women and men, recognizing that an individual’s knowledge is shaped by their unique relationships with the ecosystem and their intersecting identities31,90,91.

Participatory process

Resource users and public perceptions and beliefs have a profound effect on the success of ecosystem restoration, particularly in ensuring stakeholder buy-in, effective implementation, and long-term sustainability of the project92. However, in larger-scale ecoscape restoration projects, the breadth of governance levels and the involvement of multiple jurisdictions can constrain participatory processes. These projects often require significant time and resources to ensure effective engagement, and challenges such as determining who represents diverse stakeholder groups and addressing power imbalances can further complicate the process. Without addressing these complexities, participatory processes risk becoming exclusionary or ineffective93. Parties involved in restoration projects in Mexico commented that lack of local participation was a major limitation for community-based restoration and stressed the necessity to integrate community members during the decision-making processes. This could stem from a lack of community organization, differing perceptions of restoration efforts and their benefits, or conflicting objectives for participation, such as prioritizing economic gains over building social capacity69. Therefore, properly engaging and sparking resource users’, rightsholders’, stakeholders’, and the public’s interest is key to the sustainability of restoration initiatives.

Participatory processes in ecoscape restoration projects must address issues of representation and equity to avoid power imbalances and ensure procedural fairness. Mechanisms for engagement should prioritize inclusivity, enabling voices from marginalized or less powerful groups to be heard alongside more dominant stakeholders. Participatory processes provide methods and tools for effective resource user engagement, laying the groundwork for resource users to influence decisions and processes, and are key to procedural equity. Through participatory processes, equitable opportunities are offered to all members, and everyone is welcome in the decision-making process56,59. Special attention must be paid to local and international power dynamics to avoid the “tyranny of participation” characterized by elite manipulation, exploitation, and intimidation of communities in the name of ‘community participation’61. Ecoscape restoration projects inherently involve multiple governance levels, posing challenges for broad participation. Representation must be carefully managed to ensure inclusivity and equitable decision-making. Addressing asymmetries in power and resources, such as through capacity-building initiatives and representative training, can mitigate disparities. For instance, structured governance frameworks that allocate roles among tribal leaders, local NGOs, and national agencies can create a level playing field for diverse interest holders57. Though resource-intensive, these processes are vital for achieving socially and ecologically just restoration outcomes. While participatory processes look different for each individual project and circumstance, Webler and Tuler94 and the Initiative for Climate Action Transparency92 have identified six factors for successful implementation of participatory processes (Table 2).

To engage in participatory processes in seascape restoration, it is important for practitioners to begin by identifying the full diversity of resource user groups across habitats and familiarizing themselves with resource user perspectives, values, and backgrounds, including accommodating multiple languages spoken by members of the community. This can be achieved through various research and communication mechanisms including focus groups and hosting or attending community meetings to share restoration goals and receive feedback56,69,92. However, the larger scope of ecoscape restoration requires tailored approaches to balance the input of diverse stakeholders with the need for efficiency as engaging all actors in these cases is resource and time intensive. Effective participation in these projects could instead involve leveraging representative institutions or stakeholder coalitions that can justly convey the priorities of multiple groups. Resource users’ involvement can further be encouraged by utilizing intrinsic and extrinsic motivators, which should be adapted to each group to be most effective. Possible intrinsic incentives include appealing to values or ethics, autonomy, and self-actualization of resource users59,95. Project leaders can also create economic, social, physical, or legal incentives to promote engagement from resource users59,95; however, caution should be used, as there is evidence that such incentives “crowd out” intrinsic motivations and can undermine conservation efforts in the long-term96. If certain jobs are negatively affected by the restoration project, one possible response is the creation of alternate or supplementary livelihoods.

For example, local fishermen can become involved in regular maintenance and monitoring of coral reef nurseries if their usual livelihoods become disrupted54,95. However, alternative livelihoods are not always appropriate; interventions based on flawed assumptions about resource users’ needs, aspirations, and motivations are unlikely to achieve conservation objectives97 and in some cases can create new injustices and incentives to harvest illegally, exacerbating social and ecological challenges98. Finally, progress and results of the restoration project should be disseminated to the appropriate resource users and community members after each phase of implementation via meetings, outreach materials and media, or other locally appropriate mechanisms. This not only allows for open communication but enables feedback and improvements to the restoration process69,92,99. Ensuring transparency in these large-scale projects is essential for maintaining trust and adapting to stakeholder feedback. Restoration practitioners can utilize existing resources when planning their participatory processes, such as NOAA’s Introduction to Stakeholder Participation document99 and the Initiative for Climate Action Transparency’s (ICAT) Stakeholder Participation Guide92. Local partners can also provide guidance on local protocols to ensure the cultural appropriateness of the approach.

There are several examples of the use of participatory processes in community-based restoration and management. Participatory processes were used in a collaboration in Botswana between local pastoral communities and development researchers to reduce desertification. A bottom-up process was integrated with participatory, expert, and scientific evaluation to provide guidelines for community-based rangeland monitoring and management. This process has resulted in enhanced community empowerment and provided a formal framework for participatory involvement in the identification and evaluation of degradation indicators that can be utilized by the Ministry of Agriculture for future community-based projects100. A river restoration project in Montana engaged resource users through public meetings, one-on-one interactions, and citizen action groups, resulting in a successful restoration project that was marked by mutual respect between all involved parties and that created a sense of place for residents101. Finally, the Puerto Morelos reef marine protected area was co-established and maintained through the identification of community leaders; discussions between resource users, NGOs, reef scientists, and government agencies; consensus of the need for reef protection; and continuous problem-solving processes between the government and resource users102.

Equity

The importance of ensuring equity in conservation, public policy, and environmental management has been increasingly emphasized as important over the last two decades8,103,104. However, conservation initiatives have been criticized for adopting exclusionary methods, separating people from nature, and favoring Western values and worldviews105,106,107,108,109. Habitat restoration, specifically, often involves inequity in the societal disparities that lead to the need for restoration, how restoration projects are prioritized and where they take place, and how the costs and benefits of the restoration project are distributed. For example, in Central Kalimantan’s tropical peatlands, the push for restoration has often conflicted with the needs and rights of local communities, who were historically marginalized in decisions regarding land use and conservation efforts. Restoration projects in these regions have sometimes prioritized global conservation goals over local development needs, leading to unequal distribution of benefits and perpetuating existing social inequalities110,111. It is important to acknowledge situations where restoration initiatives fail to engage with or benefit local users. Equitable benefit-sharing ensures that local users—who are often stewards of the environment—gain tangible and sustainable advantages from restoration efforts. Restoration projects that address human needs, such as promoting sustainable resource use or livelihood diversification, and that prioritize the fair distribution of benefits are essential to avoid exacerbating existing inequities112.

Seascape restoration highlights the need to balance ecological goals with local benefit-sharing. While property rights are typically less contentious in the ocean than on land, exceptions exist, particularly in regions where traditional rights holders govern access to marine resources113,114. In Palau, for example, specific portions of water are traditionally owned and used for farming, requiring permissions from these owners before any restoration can occur. Failure to navigate these rights equitably risks creating social tensions, even when ecological outcomes are positive. While concerns about neocolonialism in top-down restoration efforts are valid, it is important to also account for contexts where local communities’ actions contribute to degradation. In these cases, restoration efforts that address human needs—such as promoting sustainable resource use or livelihood diversification—and demonstrably share benefits equitably among local users should not be conflated with top-down or internationally-driven projects that fail to benefit local communities. This underscores the importance of distinguishing genuine restoration efforts—those that equitably benefit local users—from elite-driven coastal development projects that prioritize profit over community well-being. Such projects, often catering to private tourism or exclusive landowners, can exacerbate inequalities in access to and benefits from coastal and marine resources20.

Additionally, global restoration projects frequently highlight overlooked equity issues, particularly regarding who bears the costs of restoration and who reaps the benefits109. Wells et al. emphasize the importance of ensuring that restoration efforts address not only ecological needs but also social justice by actively involving marginalized groups in decision-making and implementation. Although equity has been recognized as a critical consideration in restoration initiatives, there remains a lack of explicit guidance on how to effectively achieve equitable outcomes in ecoscape restoration projects40,52,53,109,115. Prioritizing equity in restoration is essential not only to respect the communities in which restoration takes place but also to achieve more successful restoration outcomes by increasing mutual respect, incorporating local-ecological knowledge, and encouraging community participation58,109,116.

Pascual et al. define four dimensions of equity that should be considered in conservation and restoration: procedural, distributional, recognitional, and contextual (see Table 3 for definitions)117. All four dimensions of equity must be incorporated early and throughout the planning and implementation of restoration initiatives.

Key steps include privileging local knowledge and practices through knowledge coevolution and ensuring the participation of people directly or indirectly impacted by the restoration project. This can be achieved by discerning local rights and access, understanding local power dynamics, strengthening community organizations, and ensuring local groups have an equal voice in decision-making, project design, and planning118. Acknowledging the unique roles that different identity groups play in utilizing and preserving natural resources across various cultures is also important119. Promoting engagement from diverse identity groups, especially those disproportionately affected by environmental threats or restoration work, will help align restoration projects with environmental justice goals120.

In Palau, local conservation and education non-profit Ebiil Society has led a community-engaged initiative to restore depleted sea cucumber populations through farming, following their overharvest for export markets. Though it was primarily men that benefited from the export of sea cucumbers, it is women who have relied on and stewarded the fishery for generations and who have borne the burden of the fishery’s collapse121. Therefore, it was the ecological knowledge of these women that was prioritized, alongside Western scientific approaches to sea cucumber rearing122. These women have also conducted the release and regular monitoring of juveniles into the seagrass habitat. Their engagement and leadership has not only enabled greater project efficiency and effectiveness, it has also honored their roles as knowledge holders and environmental stewards to ensure that in the long-term, the project has continued to meet their changing needs, including the identification of other interventions to restore, revive, and sustain the fishery.

Adaptive co-management

Adaptive co-management, which involves collaborative decision-making and shared management responsibilities between local communities and government agencies, has been proposed and implemented as an alternative management method to address challenges faced by both top-down and bottom-up systems55,123,124,125. Top-down governance systems often struggle with balancing stakeholder engagement and environmental outcomes, as seen in Sweden’s coastal management efforts. Strict, centralized regulations failed to accommodate the knowledge and interests of local actors, leading to poor stakeholder buy-in and reduced long-term success126. Similarly, in the Chesapeake Bay, USA, top-down governance did not effectively address local environmental needs, resulting in unsustainable practices that worsened ecosystem degradation127. On the other hand, bottom-up systems, while fostering local engagement and ownership, can face coordination and continuity challenges and limited scalability. Local-level efforts in Madagascar’s forest management demonstrated that bottom-up governance, without higher-level support and resources, struggled to manage large-scale ecosystem pressures, leading to fragmented conservation efforts128. Additionally, bottom-up governance can struggle with authority, as local actors may not have the legal or formal power to enforce regulations or coordinate large-scale actions, which can limit the impact of their conservation efforts129. Adaptive co-management seeks to overcome these issues by integrating both local knowledge and institutional support, creating a more flexible and inclusive management system that is better suited to addressing complex ecological and social challenges55.

Adaptive co-management promotes collaborative and flexible, learning-based governance mechanisms that involve cross-collaboration between local communities, resource users, organizations, and government agencies55,57,124. This decentralized power structure allows decision-makers to be more responsive to ecosystem changes and promotes equity among resource users, efficient decision making, and increased capacity-building57,130. Incorporating adaptive co-management strategies into restoration projects can prevent “green grabbing,” a practice where foreign entities, often environmentalists or conservationists, take control of resources for conservation purposes, driven by neoliberal policies131. These policies can result in the displacement and disenfranchisement of local communities. For instance, in the creation of a MPA in Langebaan, South Africa, the international environmental NGOs and government failed to consult with the local fishing community during the initiative and in turn caused them to lose their livelihoods132. By ensuring that resources remain in the hands of the local parties who directly rely on them, adaptive co-management helps safeguard the rights and livelihoods of these communities131.

Adaptive co-management can be achieved through trust-building and power sharing between managers and resource users via open discourses and meetings early in project planning124. Aligning local and high-level goals is key to adaptive co-management, which can be done by engaging rights holders, traditional owners, and other resource users to identify priorities, perspectives, and concerns. Rather than merely consulting the community, participatory methods such as community-led workshops or joint decision-making forums can be employed. These approaches allow community members to contribute directly to governance and restoration strategies, ensuring they have a genuine role in shaping outcomes124. Such methods foster a more balanced distribution of power by making communities equal partners in managing the project’s direction and execution. Understanding the local political structures and hierarchies remains crucial for navigating political complexities and leadership structures with care and ensuring that all voices are heard and respected39,70. For adaptive co-management to be successful, evidence-based management should be prioritized during project planning and implementation, and leaders should be willing to reorganize the project as it progresses to adapt to changing needs and outcomes57,58,133. While adaptive co-management relies on building trust and shared decision-making among interest holders, establishing legal and legislative frameworks is critical for sustaining a restoration project’s legitimacy, particularly amid shifting political landscapes. Such frameworks not only safeguard co-management agreements but also enhance interest holder confidence and compliance. As emphasized by Cosens et al., embedding co-management within legal and institutional structures allows for the flexibility necessary to adapt to ecological and social changes while maintaining accountability and trust129. Furthermore, co-management processes can serve as catalysts for policy and legislative reforms, progressively aligning governance systems with collaborative restoration goals. By co-creating management systems that align with both local practices and legal institutions, interest holders can leverage co-management to secure ecological restoration outcomes and promote governance reform in a way that remains resilient to political shifts.

There are multiple examples of the successful incorporation of adaptive co-management into restoration, which often address not only ecological but also social crises related to representation, authority, and historical inequalities124,125,130. Co-management is frequently driven by grassroots advocates and organizations that have been lobbying for such an approach long before an ecological crisis emerges. The drastic decline of healthy reefs along the Great Barrier Reef in Australia led the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park authority to implement an ecosystem-based adaptive co-management strategy with community members, scientists, and government agencies134. In this case, significant social groundwork had already been laid by grassroots advocates and community organizations long before coral bleaching events occurred. These groups had been lobbying for co-management structures to ensure that local communities had a say in the governance of the Great Barrier Reef135. When a mass coral bleaching event struck, the convergence of stakeholder concerns—ranging from commercial fishers to tourism operators—allowed for a co-managed approach to be adopted swiftly. This alignment of local and national priorities facilitated coordinated action for coral conservation, demonstrating the importance of pre-existing social networks in driving effective and inclusive ecosystem management134,135,136.

In southern Sweden, an adaptive co-management system was employed for wetland landscape governance as a reaction to perceived threats among resource users to the area’s cultural and ecological values. This approach involved shared decision-making between local stakeholders, government agencies, and scientists to balance ecological sustainability and cultural preservation. The system replaced previous top-down governance, which had failed to address the complexity of the area’s social-ecological issues137. In the Southern Ocean, adaptive co-management brought together licensed fisheries, conservation activists, and governments to address illegal fishing of toothfish. This collaboration emerged in response to the ‘toothfish crisis,’ where illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing threatened the species. A diverse set of actors, including NGOs, national governments, and the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), co-managed the crisis by implementing stringent compliance mechanisms, such as satellite monitoring and port inspections, to curb illegal activities and ensure sustainable fishing practices. NGOs, while lacking formal jurisdiction, played a crucial role in advocacy and raising public awareness, which influenced governance and compliance mechanisms. For example, NGOs like ISOFISH partnered with the fishing industry to collect intelligence on IUU operators and lobbied governments for stronger enforcement measures. This dynamic complemented the formal mechanisms of CCAMLR, which included sanctions and compliance frameworks, highlighting the synergistic role of diverse actors in addressing governance challenges138. However, this dynamic is distinct from traditional co-management, which typically involves shared jurisdiction and decision-making authority between governments and local actors. In these cases, adaptive co-management resulted in improved cooperation among resource users, positive ecosystem shifts, and increased capacity to deal with new challenges99,134,135,137,138.

Consistent monitoring

A key component of restoration success, yet one of the greatest challenges in restoration, is consistent long-term monitoring and upkeep of the project139. Many habitat restoration studies are dominated by short-term projects, likely due to the relatively short time available for research projects, funding timelines, and the pressure to publish27. However, if researchers intend to make effective change and ensure the restoration of habitats, extending the length of monitoring and upkeep is necessary. This includes monitoring the health of the whole restoration system, including ecological, social, cultural, and economic impacts and outcomes140. Establishing standardized monitoring protocols, such as the framework created by the Society for Ecological Restoration (SER), can ensure that culturally comprehensive and universally adaptable methods are used141.

A key strategy to ensure long-term monitoring is to support locally-led initiatives, including prioritizing local ecological knowledge, embracing existing capacity, and training of new participants as necessary. Local knowledge may include traditional and/or Western scientific knowledge. In addition to providing additional safeguards to the success of the project, community-based monitoring will aid in eliminating power imbalances and foster trust in the project from the community69. To have effective community-based monitoring it is also necessary to invest in proper and sufficient monitoring equipment for use by the community members; these tools will ideally be purchased from a local vendor. Investing in high-quality materials may improve measurement accuracy, and sourcing from local businesses can ensure continued participation in and maintenance of the project after non-local partners have exited58,95. Lastly, it is important to incorporate frequent check-ins with community members to ensure teams are working efficiently, are equipped with the necessary tools, and everyone’s needs are met. This also enables adjustments to the monitoring system to be made as necessary54.

Community-based monitoring, citizen-science programs, and collaborative efforts have been shown to be effective means of implementing environmental restoration projects57,69,142. Heeger et al. successfully implemented a coral farm for reef rehabilitation and as a livelihood option for fisherfolk in the Philippines, more than doubling their monthly income in half the number of hours worked143. The fisherfolk are involved in outplanting, maintenance, and monitoring of the coral farm. Community-led seagrass restoration efforts in the Mediterranean, involved engaging local divers and snorkelers as citizen scientists. These volunteers were trained to collect data on seagrass health and distribution using the MedSens index, which was designed to bridge the gap between citizen science data and management needs, ensuring the inclusion of local knowledge in decision-making144. Additionally, Walters et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of public participation in living shoreline stabilization efforts in popular tourist areas145. Volunteers were actively involved in bagging oyster shells, which were then used to create living shorelines, helping to reduce erosion and restore habitat. This hands-on involvement fostered community engagement and provided crucial support for the restoration project.

Conclusions

In the face of climate change, the social, cultural, and ecological institutions that are holding coastal communities and their worldviews together are being challenged. Coastal communities are some of the first to experience the impacts of climate change, in particular sea level rise, warming oceans, and an increase in storms. These communities have a long and rich history of maritime exploration, reliance on natural resources, and a culture of traditional storytelling that passes down collective knowledge and wisdom through generations. If they were lost, these cultural traditions and ways of life would be an enormous loss to humanity. Protecting these traditions and institutions is critically important. While climate induced threats are new challenges to these communities, coastal communities have experience recovering from and adapting to other threats associated with coastal living for millenia. The cultural connections, knowledge, and traditions that are inherent in these communities have given them an incredible capacity for adaptation which has allowed them to thrive despite these challenging conditions. Uplifting, prioritizing, and respecting these traditional practices and knowledge will be a critical component of climate adaptation strategies, including in seascape restoration. This includes building robust partnerships between Traditional and Western scientific knowledge holders (recognizing an individual can hold one or both identities) that can be leveraged to develop holistic, collaborative, and innovative solutions to climate threats.

Traditional Knowledge plays a crucial role in developing and executing habitat restoration projects, but true success requires more than just tapping into this knowledge—it demands meaningful engagement. In Australia, studies have shown that projects achieve better outcomes when managers and project sponsors take the time to build relationships with Traditional Owners, including spending time with Elders to understand both their knowledge systems and the community’s priorities146. This approach goes beyond gathering information and ensures that the community’s perspectives are central to shaping the project135. It is also important to recognize that Traditional Owner communities often face competing priorities, such as addressing health, welfare, and housing needs, which may limit their capacity to fully engage in restoration efforts147,148. Understanding whether these communities have the resources, including personnel and time, to participate meaningfully in the project is essential for managing expectations and ensuring the project’s success149. Flexibility with project timelines is equally important, as community involvement may vary depending on available resources and competing demands136,149. By acknowledging these challenges early on and fostering collaborative partnerships, restoration projects can be more sustainable and respectful of Traditional Owner communities, ultimately leading to better restoration outcomes150.

In this paper, we provide a framework for implementing just seascape restoration. Centering community perspectives and needs should be considered as early as possible in the planning process, included in funding applications, and be continually re-assessed as the project progresses. Implementing these recommendations will take additional time and financial resources, however, the long-term sustainability and effectiveness of collaborative and just initiatives has been shown to be worth the investment, beyond the intrinsic value of justice. Prioritizing just practices in restoration will improve the potential for positive short- and long-term restoration outcomes, enhance adaptive capacity, and promote equity93.

We highlight knowledge coevolution, adaptive co-management, equity, participatory processes, and consistent monitoring as means of achieving successful and sustained just seascape restoration. Collaboration, flexibility, and respect are key themes that are found across all five of our concepts and result in overlap of ideas and practices between recommendations. Implementing adaptive co-management into restoration will institutionalize community and resource user involvement, allow decision makers to be more adaptive to changes, and promote equity among resource users55,124,130. The coevolution of Western scientific and local ecological knowledge by employing a Two-Eyed Seeing approach will reduce uneven power dynamics, increase adaptive capacity, and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the restoration system and its implications both ecologically and socially70,82. Prioritizing equity in restoration will increase mutual respect and encourage community participation58,109,116. Participatory processes will enable effective resource user engagement and provide more equitable opportunities for all members to engage in decision-making processes. Long-term monitoring of restoration systems will be possible through the leadership of community members and resource users. Building restoration projects capable of responding and adapting to change through adaptive management and personalizing materials and methods to local communities will strengthen the ability of restoration systems to persist into the future58,119,151,152.

While we present a comprehensive framework for just restoration practices, we recognize the importance of putting this framework into practice through real-world application. Future efforts should aim to test and refine the framework by applying it to seascape restoration projects, incorporating metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of each key pillar, such as co-management, participatory processes, and equity. Testing and adapting this framework across various ecosystems—such as coral reefs, seagrass beds, mangroves, and wetlands—would provide valuable insights into its practical application, highlight areas for improvement, and demonstrate its versatility. We encourage researchers and practitioners to engage in this process of iterative refinement, as it will contribute to the continuous improvement of just and sustainable restoration practices. A follow-up study that evaluates the framework’s success in specific case studies could offer critical learnings, moving the framework from theory to tangible application. By applying this framework, we can begin to bridge the gap between scientists, practitioners, and community members to create more just and sustainable restoration initiatives that prioritize and respect local knowledge and values.

Statement of positionality

As co-authors from diverse backgrounds, including scientists and practitioners from decolonizing Palau and its former colonizer the United States, we acknowledge and strive to continually question the influence that colonization has had on our own practices and beliefs. This is a never-ending process that necessitates constant self-reflection, listening, and learning. We have all had our beliefs shaped by colonial legacies, and some of us have been directly and negatively impacted by colonialism. Through this framework, we aim to provide an authentic way for researchers and practitioners to meaningfully and respectfully partner with resource dependent communities in seascape restoration. We emphasize that collaborations, built on mutual respect and understanding, are essential in achieving successful restoration outcomes. Our commitment to this process reflects our dedication to decolonizing our practices and fostering inclusive and equitable approaches to ecological stewardship.

Responses