A glycan foldamer that uses carbohydrate–aromatic interactions to perform catalysis

Main

Folding endows biomolecules with functions. In proteins, the strategic proximity of chemical functionalities achieved through specific geometric arrangements facilitates chemical reactions by enhancing kinetics and ensuring regio- and/or stereoselectivity1,2. Inspired by nature, miniaturized analogues of these biomolecules have been created, such as peptide turns for stereoselective catalysis (Fig. 1a)3,4,5,6 and synthetic foldamers to accelerate chemical transformations7,8. This process not only introduced novel synthetic methodologies5,6,9,10,11,12,13 but also served as impetus for the development of efficient syntheses of foldamer motives14,15,16,17 and pushed the boundaries of structural analysis18,19. These folded molecules share a common design principle: a programmable backbone forming a stable three-dimensional conformation sustained by intramolecular non-covalent interactions that can be systematically adjusted to tune specific interactions with the substrate(s) and/or reaction intermediate(s). We wondered whether a similar design can be applied to other biopolymers, such as glycans, to expand the portfolio of functional oligomers.

a, Examples of folded oligomers used in catalysis. b, A visualization of carbohydrate–aromatic interactions between a Trp residue and a Gal involved in carbohydrate recognition (PDB ID: 5ajb). c, The chemical structure of Sialyl Lewis X and its modification to access a glycan foldamer that performs catalysis. GlcNAc, blue square; Glc, blue circle; Gal, yellow circle; Neu5Ac, purple rhombus; Fuc, red triangle; Rha, green triangle. The monosaccharide residues are represented following the Symbol Nomenclature for Glycans (SNFG)67.

Glycans offer a pool of over 100 monosaccharides, intrinsic chirality and several options for directional functionalization, making them prime candidates for crafting modular, functional oligomers20. Moreover, glycans can engage in multiple interactions with a substrate due to synergies of hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic effects21. It is therefore not a surprise that the term artificial enzyme was first coined for a cyclodextrin (CD)-based structure22, a cyclic α-1,4 linked oligomer of glucose (Glc) (Fig. 1a). CDs leverage the amphiphilic nature of carbohydrates to form a hydrophobic cavity that can encapsulate guest molecules, while exposing the hydrophilic hydroxyls to the solvent. These groups can be further functionalized23,24 to achieve a broad spectrum of functions, including catalysis25,26,27,28,29,30. Since their first discovery in 1891 (ref. 31), the chemical space of CDs has been extensively explored, resulting in the smallest known CDs32 and enantiomeric l-CDs33. Still, the functional carbohydrate space remained locked within the cyclic α-1,4 Glc framework.

Given the success of peptide-based catalysis and the unexplored potential of functional glycans, we set out to identify a glycan sequence capable of performing a catalytic reaction. This challenge was envisioned to push the boundaries of glycan synthesis and structural analysis, while increasing our understanding of carbohydrate interactions with other molecules. Here we present the design, synthesis and structural analysis of a carbohydrate sequence capable of (1) folding into a defined conformation, (2) coordinating a substrate via weak carbohydrate–aromatic interactions and (3) performing a catalytic transformation.

Results and discussion

General design

To craft our glycan catalyst, we sought inspiration from nature, beginning with an exploration of the diverse ways that glycans can coordinate substrates. In the carbohydrate-binding domains of proteins, aromatic moieties are abundant, facilitating binding via CH–π interactions (Fig. 1b)34,35,36. These interactions, involving the electrostatic attraction between the π electron cloud of an aromatic ring and the electron-poor C–H bonds of the carbohydrate ring, are fundamental for carbohydrate recognition in aqueous environments, as demonstrated with monosaccharide models and computational calculations35,37. CH–π interactions occur preferentially at the α-face of pyranosides, where the majority of axial C–H bonds are present38, and were exploited in artificial systems for glycan recognition39,40. Our strategy looked at CH–π interactions from the opposite perspective: we aimed to harness CH–π interactions to recruit an aromatic substrate and position it in proximity to the catalytic site of our glycan catalyst.

To design the backbone of our glycan catalyst, the naturally occurring Sialyl Lewis X41 served as the blueprint (Fig. 1c). Sialyl Lewis X is a glycan frame that possesses an extended sialyl acid (N-acetylneuraminic acid, Neu5Ac) arm connected to a rigid glycan turn (Gal–GlcNAc–Fuc, where Gal is galactose, GlcNAc is N-acetylglucosamine and Fuc is fucose), sustained by an unconventional H-bonding42. In our adaptation, the Neu5Ac unit was replaced with a β-linked Gal unit to form CH–π interactions and recruit an aromatic substrate (Fig. 1c). The β-Gal is particularly suited for this role owing to its three axial and one equatorial C–H bonds on the α-face, making it ideal for engaging in CH–π interactions35. Further modifications to the Sialyl Lewis X frame were made to optimize the glycan structure for its catalytic role: (1) the Gal unit was replaced by a Glc, avoiding multiple interaction sites (that is, two Gal units) with the aromatic substrate and orienting the α-face of the terminal Gal towards the inside of the glycan foldamer; (2) the Fuc unit was exchanged with rhamnose (Rha), featuring an equatorial hydroxyl group at C-4 for installation of the catalytic group in proximity to the key interaction site; (3) the branching GlcNAc was converted into a Glc, easing the synthetic steps, while preserving a similar folding behaviour43,44.

Using CH–π interactions to recruit an aromatic substrate

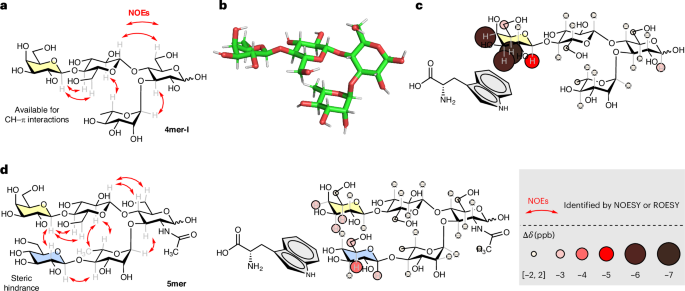

The initial target glycan frame (4mer-I) was prepared by automated glycan assembly (AGA) (Supplementary Information section 3.5.2) to study its conformation and ability to engage in CH–π interactions with an aromatic substrate. Multiple nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments (1H NMR, correlation spectroscopy (COSY), heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) and selective one-dimensional (1D) total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY); Supplementary Information section 4.4) permitted the assignment of all the protons in the molecules. The downfield shift of Rha-5 indicated that the presence of the unconventional H-bonding stabilizing the folded conformation of the turn motif42,43. Nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) analysis supported by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Information section 4.3) confirmed the rigid conformation of the turn motif (Supplementary Fig. 16) and the correct orientation of the Gal arm (that is, with the α-face pointing towards the hydroxyl group of Rha C-4).

a, Experimentally observed nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) extracted from NOESY NMR experiments for 4mer-I (red arrows) confirming the rigid conformation of the turn motif and the orientation of the Gal arm with the α-face pointing towards the hydroxyl group of Rha C-4. b, A representative snapshot of 4mer-I obtained from MD simulations. c, Experimentally observed CH–π interactions for 4mer-I (3.5 mM) incubated with Trp (10.5 mM) indicating CH–π interactions localized on the Gal unit of 4mer-I. d, Experimentally observed NOEs extracted from ROESY NMR experiments for 5mer confirming its folded conformation and CH–π interactions for 5mer (3.5 mM) incubated with Trp (10.5 mM); only minimal interactions are detected on the Gal (yellow) and Glc (blue) residues.

l-Tryptophan (Trp), frequently present in the carbohydrate-recognition site of proteins35,45, was chosen for the CH–π interaction analysis. 4mer-I (3.5 mM) was incubated with Trp (10.5 mM) in water, and the mixture was analysed by 1H NMR and selective 1D TOCSY (Supplementary Information section 4.5.2)35. Chemical shift changes localized on the Gal unit (Fig. 2c) indicated CH–π interactions between 4mer-I and Trp35. A minor contribution of unspecific interactions (including hydrophobic effects) could also be involved in such interactions46.

To further support the position of the interaction between 4mer-I and Trp, we synthesized 5mer (Supplementary Information section 3.5.7), in which the α-face of Gal was hindered by the presence of a Glc residue on the lower arm. Rotating-frame nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY) experiments (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 43) confirmed the proximity between the α-face of Gal and the Glc unit. Comparative analysis confirmed that obstructing the α-face of Gal in 5mer diminished CH–π interactions with Trp (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Information section 4.5.4). Similar results were obtained when the CH–π interactions analysis was performed with the neutral 5-OH-indole instead of Trp (Supplementary Information sections 4.5.3 and 4.5.5), ruling out the influence of potential ionic interactions.

Taken together, these observations proved that 4mer-I folds into a rigid conformation and can recognize an aromatic substrate via CH–π interactions localized on the Gal unit. Thus, 4mer-I was further functionalized to install a reactive group capable of promoting a chemical reaction on an aromatic substrate.

Insertion of a reactive functional group

For the functionalization of our glycan foldamer, we focused on groups enabling the Brønsted-acid type of catalysis47, used in wide range of organic transformations such as C–C/C–X bond formation48,49,50. The functionalization was strategically planned at the equatorial hydroxyl group of Rha C-4 (Fig. 3), proximal to the Gal α-face. Inspired by binaphthol-derived acid catalysts51,52, we designed 4mer-II, which incorporates a phosphoric acid group. The target glycan was prepared by AGA from BB1-3 and BB5 following iterative cycles of glycosylation and deprotection. The solid bound tetrasaccharide, carrying a free hydroxyl group at Rha C-4, was further subjected to P–O coupling followed by oxidation to afford the protected phosphorylated intermediate53. Cleavage from the solid support promoted by ultraviolet irradiation and global deprotection afforded the target 4mer-II in a 40% overall yield (Supplementary Information section 3.5.3). A similar strategy was used to construct the sulfated tetrasaccharide 4mer-III. AGA was followed by sulfation on solid phase54, photocleavage and global deprotection to give 4mer-III in a 28% overall yield (Supplementary Information section 3.5.4). 4mer-IV carrying a carboxylic acid group was synthesized using the carboxylic ester functionalized BB7 in place of BB5. AGA, photocleavage and global deprotection resulted in a 28% overall yield (Supplementary Information section 3.5.5).

AGA and post-AGA steps to obtain three glycan structures starting from protected monosaccharide building blocks (represented with SNFG icons surrounded by grey dots). Overall yields are reported in parentheses. Reaction conditions for AGA and post-AGA are reported in the Supplementary Information. The colours of the chemical structures relate to the colours of the icons for the various functionalization processes: blue for phosphate modification, orange for sulfate modification and brown for carboxylic modification.

4mer-II, 4mer-III, and 4mer-IV were analysed by NOESY or ROESY (Supplementary Figs. 21, 26 and 32) to verify that the functional modifications did not compromise the conformational integrity of the glycan backbone. The observed spatial correlations for all modified 4mers were consistent with those of the original 4mer-I, confirming that these functional groups did not alter the foldamer conformation (Supplementary Figs. 22, 27 and 33). An additional spatial correlation between Glc′ H-2 with Rha H-6 was observed for 4mer-II and 4mer-III (Supplementary Figs. 21 and 26) and to a lesser extent for 4mer-IV (Supplementary Figs. 31 and 32), indicating a slightly more rigid conformation than 4mer-I (Supplementary Fig. 16). This result was further supported by MD simulations of 4mer-I versus 4mer-III (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6) and might be connected with the electron-withdrawing nature of the acid substituents, which strengthens the unconventional H-bonding between Rha H-5 and the endocyclic oxygen of Glc in the turn unit55.

We then investigated the impact of the ionic groups on CH–π interactions, following the same experimental protocol used for 4mer-I and Trp (Supplementary Information sections 4.5.6–4.5.8). The phosphorylated and sulfated variants, 4mer-II and 4mer-III, exhibited a reduction in CH–π interactions compared with the neutral 4mer-I, which can be attributed to hinderance of the bulky acid groups and the increased rigidity of the glycan scaffolds. By contrast, 4mer-IV displayed interaction levels akin to those of the neutral 4mer-I (Fig. 4b). We reasoned that the extra methylene group in 4mer-IV may offer enhanced flexibility to better accommodate the aromatic group in proximity to the Gal unit.

a, Pictet–Spengler reaction between Trp 1 and propionaldehyde 2. aInteractions with Trp are defined from the sum of Δδ (ppb) for all the protons pointing to the α-face (H-1, H-3, H-4, H-5 and H-6 for 4mer-II–IV and H-1, H-3, H-5 and H-6 for 4mer-V): weak <20 ppb, strong ≥20 ppb). bThe reaction yield was monitored by 1H NMR. cVariations from standard condition: reaction time 168 h, 2 (0.3 mmol). dOptimized condition: 4mer-IV (20%), 72 h, 37 °C, 2 (0.3 mmol). b, Experimentally observed CH–π interactions for 4mer-IV (3.5 mM) incubated with Trp (10.5 mM) and kinetic analysis of the Pictet–Spengler reaction catalysed by 4mer-IV (20%), glycolic acid (20%) or AcOH (20%), 37 °C using 1H NMR. c, Functionalization of peptides via 4mer-IV (20%) catalysed Pictet–Spengler reaction. eThe reaction was conducted in water and monitored by 1H NMR. fThe reaction was conducted in buffer and monitored by 1H NMR. r.t., room temperature.

Source data

Catalysing a Pictet–Spengler reaction with a glycan foldamer

Equipped with a set of glycan foldamers carrying a Brønsted-acid functional group, we set to test their catalytic performance in a Pictet–Spengler transformation56. The Pictet–Spengler reaction is a well-established method for the construction of asymmetric alkaloid frames, extensively explored in organic medium57,58 and, more recently, adapted to aqueous environments59,60. The latter aligns with the requirement of chemical biology, despite the challenge of typically slower reaction kinetics in such conditions.

We tested the Pictet–Spengler reaction between Trp 1 and propionaldehyde 2 in D2O (to allow NMR monitoring) at room temperature. The reaction showed negligible conversion in the absence of catalysis (Supplementary Information section 5.2) or in the presence of 4mer-II or 4mer-III as catalyst (Fig. 4a). By contrast, using 4mer-IV as the catalyst led to the formation of the desired product, albeit with a modest yield of 15 %. Longer reaction times (168 h) and an increased amount of aldehyde (0.3 mmol) improved the yield to 55% (Fig. 4a). These observations suggested that the CH–π interactions between the catalyst 4mer-IV and the Trp substrate were beneficial for the reaction.

To further validate the role of the CH–π interactions in promoting the desired transformation, we prepared a second series of catalysts containing the carboxylic acid functionality. 3mer is an analogue of 4mer-IV lacking the coordinating Gal unit and thus showing no interactions with Trp. 4mer-V is equipped with a Glc arm in place of the Gal unit. CH–π interaction analysis for 4mer-V revealed minor chemical shift changes localized on the Glc (Supplementary Information section 4.5.9). When the Pictet–Spengler transformation was performed in the presence of 3mer, the reaction yielded the desired product (Fig. 4a), but the conversion rate was notably slower than in the presence of 4mer-IV. This result stressed the key contribution of the CH–π interactions in positioning the Trp substrate near the catalytic site. Intermediate yields were obtained when the reaction was performed with 4mer-V (Fig. 4a), confirming the correlation between CH–π interactions and reaction rate.

With 4mer-IV identified as the most effective catalyst, further optimization of the reaction conditions enabled achieving an 84% conversion and a 75% yield (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Information section 5.2). Control experiments using acetic acid (AcOH), AcOH + Gal, glycolic acid and 3mer as substitutes for 4mer-IV (Supplementary Information section 5.2, entries 13, 14, 15 and 16) resulted in lower conversions and yields. Different kinetic processes were observed when 4mer-IV or other acids (AcOH and glycolic acid) were used as the catalyst, with 4mer-IV promoting the acceleration of the desired reaction pathway (Fig. 4b). Despite the multiple chiral centres in 4mer-IV, similar cis:trans ratios were detected for the control experiments. This outcome aligns with existing literature, which attributes the diastereoselectivity of the reaction primarily to the chirality of the Trp substrate, rather than the catalyst61.

Finally, we tested the glycan-catalysed Pictet–Spengler reaction to modify the N-terminus of Trp-containing peptides. The reaction could be successfully performed in both water and buffer (Fig. 4c), preserving faster kinetics than the AcOH-catalysed controls (Supplementary Information section 5.5). These findings suggest the potential of rationally designed glycan catalysts in chemical biology, for example, for the selective functionalization of Trp in proteins62,63.

Conclusions

In summary, we designed a glycan foldamer capable of catalysing a Pictet–Spengler transformation. Our design featured a conformationally stable tetrasaccharide inspired by Sialyl Lewis X. This modular glycan frame was rationally modified to include (1) a Gal unit to engage in carbohydrate–aromatic interactions with an aromatic substrate and (2) a reactive carboxylic acid group to perform a catalytic transformation. We demonstrated that our glycan could successfully recognize a Trp substrate via carbohydrate–aromatic interactions localized on the Gal unit. This interaction resulted in the acceleration of the Pictet–Spengler reaction between Trp and an aldehyde substrate in water.

These results demonstrated that glycans can be designed to perform catalytic functions. While this challenge was envisioned to push the boundaries of glycan synthesis and increase our understanding of carbohydrate interactions with other molecules, our results suggest that glycan foldamers could have important applications in chemical biology, offering water-soluble and modular catalysts for organic transformations. Our scaffold is modular and could be easily adapted to accommodate other functional groups (for example, amino groups) to open up new catalytic pathways. To this end, improvements in glycan synthesis64,65 and mechanistic studies46 are key to inspire the design of new glycan catalysts and obtain greater quantities of materials.

Lastly, these findings raise the question of whether glycans could have active catalytic roles also in natural settings, like proteins and some RNAs66. For example, it was recently reported that cation–π interactions could modulate the reactivity of selected Trp in proteins62. We speculate that carbohydrate–aromatic interactions could have similar effects and (dis)favour selective protein modifications. Similarly, natural glycans carry numerous ionic groups that might engage in interactions with a substrate and tune its reactivity, opening up new perspectives in the glycosciences.

Methods

Synthesis

The oligosaccharides were prepared using a home-built synthesizer designed at the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interface68. All details concerning BB synthesis, AGA modules and post-AGA manipulations can be found in Supplementary Information sections 2 and 3.

MD simulations

For all simulations, the modified version GLYCAM06 force field was used69. Initial conformations for single-hairpin simulations were constructed with the Glycam Carbohydrate builder and tleap (https://glycam.org/). Both compounds with a free reducing end were modelled as β anomers. The topology was subsequently converted using the Python script acpype. Both simulations were performed in water as solvent using TIP5P as the water model70. The simulation time for the single-molecule experiments was 500 ns. Bonds involving hydrogens were constrained using the LINear Constraint Solver (LINCS) to allow a 2 fs timestep. Non-bonded interactions were cut off at 1.4 nm, and long-range electrostatics were calculated using the particle mesh Ewald method71. After energy minimization (steepest descent algorithm) and before the production run, the systems were equilibrated at 300 K for 50 ns in a canonical (NVT) ensemble (constant number of particles, volume and temperature) and subsequently at 300 K and 1 bar for 50 ns in an isothermal–isobaric (NPT) ensemble. All MD simulations were performed using Gromacs 5.1.2 (ref. 72). A Nosé–Hoover thermostat73 kept the constant temperature of 303 K constant while a Parrinello–Rahman barostat74 ensured a constant pressure of 1 bar. The analysis was visualized using OriginPro 2021b. Further details on MD simulations are reported in Supplementary Information section 4.3.

NMR analysis

1H, 13C, HSQC, 1D and two-dimensional (2D) TOCSY, 2D ROESY and 2D NOESY NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 400-MR (400 MHz), Varian 600-NMR (600 MHz) and Bruker Biospin AVANCE700 (700 MHz) spectrometer. Samples were prepared by dissolving lyophilized samples in D2O. Proton resonances of the oligosaccharides were assigned using a combination of 1H, 2D COSY, HSQC, and 1D and 2D TOCSY. Selective 1D TOCSY (HOHAHA, pulse program: seldigpzs) spectra were recorded using different mixing times to assign all the resonances (mixing time d9 is 40, 80, 120, 160, 200, 350 and 450 ms). Two-dimensional TOCSY (pulse program: mlevphpp) spectra were recorded using a mixing time of d9 at 80 ms. Two-dimensional ROESY (pulse program: reosyph.2) and 2D NOESY (pulse program: noesygpphpp) spectra were recorded using different mixing times (mixing time p15 is 200 ms for ROESY and mixing time d8 is 1,000 ms for NOESY). d8 determines the duration of mixing time. It largely depends on the relaxation behavior of the investigated molecule. d9 determines the duration of the spin lock and hence over how many protons the magnetization will be distributed. p15 is the duration of the spin lock and is equal to the mixing time. The full NMR analysis of glycans and CH–π interactions reported in this article can be found in Supplementary Information sections 4.4 and 4.5.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses