A never-ending story of reforms: on the wicked nature of the Common Agricultural Policy

Introduction

In the first months of 2024, an enigmatic outburst of farmer fury swept large parts of Europe. Farmers took to the streets in several EU countries, including the largest producers of agricultural products such as Germany, France and Poland. Long columns of thousands of tractors and many more farmers rolled into numerous cities and occupied central squares, highways were blocked by heavy machinery, straw was burned and manure sprayed on government buildings. Although seemingly initiated by a random series of country-specific issues – e.g. a plan to phase out agricultural fuel subsidies and to set taxes on agricultural vehicles in Germany, the importation of Ukrainian grain into the country in Poland – the rural revolt has converged around a series of demands that call for a change in course in the direction set for Europe’s agricultural policy in the most recent revision of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and in the agricultural elements of the European Green Deal, which has the Farm to Fork Strategy at its heart. In an attempt to calm the protests, European authorities and national governments have hastily put together a series of responses. On the EU level, these encompass a pulling back of the Green Deal legislative agenda, a weakening of some of the environmental initiatives introduced in the recent CAP reform, the introduction of greater restrictions on imports of Ukrainian agricultural products and the initiation of a strategic dialogue between a key group of stakeholders on the future of agriculture.

These measures are in themselves probably limited in scope. While signalling a willingness to respond to farmers’ concerns, they are unlikely to significantly change their situation. This situation is perceived by farmers as untenable. As common themes in different member states they complain about low incomes, the burden of environmental regulation and bureaucracy, a lack of respect and about unfair trade competition1. Ultimately, the anger of EU farmers aims at the CAP as the main framework to impact the situation and development of agricultural holdings by numerous supportive and regulatory measures. Especially the 2023-2027 CAP regulations, a result of the latest reform, are perceived as unfair, unrealistic, economically unviable and self-defeating by farmers. Other stakeholders, including researchers, on the other hand, criticise the reform for not being ambitious enough with regard to environmental goals and conclude that like its predecessors it will fail to deliver significant climatic and environmental benefits2. Having a look at the last few CAP reforms, this pattern is found constantly. So far, no reform has solved the main issues the agricultural sector is dealing with in an integral and satisfactory manner. Reforming the CAP, one could conclude, is a never-ending story.

In this short article, I elaborate why the Common Agricultural Policy is so difficult to reform. To this end, research findings from different disciplines (political science, economics, agronomy, environmental science) are gathered in order to deductively develop a framework that – compared to other papers – holistically presents the complexity of agricultural policy. Based on this framework, I argue that future CAP reforms need to prioritise certain objectives and put a notion of such a prioritisation including policy measures up for discussion.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In the first section, main challenges of the agricultural sector of the 21st century are described. The second section first discusses peculiarities of the agricultural sector and of policy making in this domain before presenting interlinkages between the agri-food system and the policy making process and eventually deriving policy priorities with respect to meeting the challenges ahead. A brief last section ties together the key arguments of the paper.

Agriculture in the 21st century

Since the Neolithic Revolution, agriculture has played a vital role in human development by providing enough food and fibre for large communities, allowing forms of administration and political structures to develop, the accumulation of goods as well as specialisation, division of labour and trade. In this role, it has also shaped (rural) landscapes all over the globe. Today, agriculture is the largest user of land, worldwide as on the European level3. Consequently, the agricultural sector bears responsibility that exceeds its economic contribution of food and fibre production.

Today we know that it has not always met this responsibility, despite increasing efforts, in Europe especially since the late 1980s. It is especially the ecological branch of the sustainability concept that represents a challenge for agriculturalists. While the benefits of (modern) agriculture are immense, the sector has become a major force behind many environmental threats. Remarkably, the six Earth system processes/features that according to the planetary boundary concept (introduced by Rockström et al.4) exceed boundaries, which represent the environmental limits within which humanity can safely operate, are to a great extent linked to agriculture: climate change, biosphere integrity, biogeochemical flows, novel entities, freshwater and land-system change5. It is thus vital to ease the environmental pressure of agriculture.

However, certain trade-off relationsa and additional challenges complicate the development of proper strategies. These challenges are diverse. First, increasing population and changing consumption patterns imply that food production must grow substantially to guarantee future food security and meet future food demands6,7. Second, production needs to keep pace with increasing demands for natural resources of economies that are transforming from fossil-fuel based systems to bioeconomic ones. Third, food prices are more likely to experience shocks as a result of deregulation and from market speculation and bioenergy/biomaterial crop expansion8, while (national) food security, food safety and the livelihood of rural communities need to be guaranteed. Fourth, climate change will negatively affect food production, directly through rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, extreme weather events and pests as well as indirectly through migration and conflict9.

While the three last-mentioned challenges have become more pressing in the last 20 years roughly and have slowly found their way into agricultural policies around the globe, the first aspect of meeting food demands was and still is at the centre of political strategies in the agricultural domain. It was also the first aspect to reveal trade-offs between agricultural production and the environment. The EU’s response to this nexus was the adoption of multifunctionality as an essential aspect of its agricultural model in 1992, not least driven by growing pressure from environmental activists and the World Trade Organization (WTO). The multifunctional agriculture (MFA) concept was promoted as a response to societal expectations about the multifunctional role that modern agriculture should play, putting some emphasis on more environmental-friendly farming practices. In this concept, agricultural activity is assigned several other functions such as renewable natural resources and landscape management, biodiversity protection and social care and the upkeep of cohesion in rural areas that go beyond its role of producing food and raw material for energetic and industrial purposes10,11.

Being first addressed in the Agenda 21 documents of the Rio Earth Summit in 199212, the multifunctionality concept basically still leads the way when it comes to addressing the challenges the agricultural sector faces, however a number of similar approaches have emerged in the agricultural policy contextb. They range from the ecosystem services concept (coined by Ehrlich and Ehrlich in 198113), to sustainable intensification14, post-productivist agriculture15, alternative agriculture16, green food systems17, climate-smart agriculture18 or resilience19. All of these concepts have their strengths and weaknesses, their own angles on addressing future agricultural challenges. For policymakers, however, this might aggravate the choice of policy tools and measures to tackle the sector’s problems. They are confronted with a number of concepts and an even larger number of scientific studies putting forward one or the other of the notions. The academic world, on the other hand, is incentivised to fragment or extend the underlying concept of sustainability in search of ever more new angles that justify the publication of scientific work20,21. Drawing the right conclusions, finding correct approaches and focusing on core issues for the further development of agricultural policies is thus hampered already by a variety of co-existing, but largely overlapping concepts22 as well as by known problems of decision-making within organisations (see for example the garbage can model23 or the multiple streams framework24). These might be minor, but nonetheless relevant reasons why negotiations on reforms of the Common Agricultural Policy are lengthy procedures.

Under an ongoing debate about the farming approach that will safely feed the planet25,26, the CAP more and more tries to provide a framework that opens development paths for various agricultural systems. It generally needs to bring together current and future societal demands, environmental necessities and economic requirements of farmers with regulations of the WTO. And just like any other policy it should be underpinned by scientific findings and theory27 – emphasising the sector’s challenges rather than specific concepts. This also means that policy outcomes need to be measured and evaluated against policy goals. In the case of agricultural policy, it is crucial to assess micro-level effects, i.e. farm production responses, in areas such as multifunctionality, market deregulation, productivity and innovation as different farms are likely to respond differently to new regulations. This task requires gathering, combining and providing high-quality data by agricultural and environmental authorities. It is a crucial one when it comes to improving the agricultural policy within the European Union. A closer look at the CAP reveals that both gathering the right data needed, but especially designing the right policy is challenging.

The Common Agricultural Policy as a response to characteristics of the agricultural sector

The CAP’s importance is not only explained by the developments described above, but also by certain economic peculiarities of agriculture, which cause market imperfections. First, farms are geographically spread and exist in large numbers. Collecting, treating and selling agricultural products (with limited durability) on the other hand is organised by few processers, wholesalers and retailers. Market power is thus unevenly distributed – the existence of oligopsony power in agriculturec has been reported for example by Rogers and Sexton28 and Kopp and Sexton29 – if a price or production coordination among farmers does not exist. Such a coordination, however, involves high transaction costs30,31, which as conceptualised by transaction cost theory32 and defined by North33 are costs of i) contact, finding partners and the product; ii) contract, negotiating an agreement; and iii) control, monitoring the effort of the contract partnerd. The great number of farms also means that individual producers have no influence on the price of the product. Individual farmers face a situation of perfect competition, which rarely exists in other sectors. Nedergaard31 states that the competitive situation in agriculture might explain the structural income problem of the sector to some extent and fosters structural change. The link between structural change and competition between farms has also been suggested by Chavas34. Furthermore, agriculture is characterised by largely immobile production factors, which reduces flexibility in response to changing market conditions. Second, farmers produce on risk markets. They lack vital information concerning future weather conditions, future prices, exchange rates and other farmers’ production35. Third, agricultural production is based on land. Olson36 found in 1985 that production based on land complicates coordination and management and lets diseconomies of scale to be reached at comparatively low levels of turnover, which in turn explains the large number of farms. Fourth, costs of moving resources from farming to non-agricultural sectors are internalised, i.e. paid by the farmer, advantages of structural change are externalised37. Fifth, agriculture as an activity bound to land is subject to market failure linked to market power (as just explained), positive and negative externalities, public and/or common goods and information shortcomings. The extent to which market failure (with respect to public/common goods and externalities) actually occurs largely depends on the jointness in production between commodity and non-commodity outputs10.

The CAP can be considered as a toolkit that tries to address the aforementioned peculiarities of the primary sector. However, its design is not only influenced by the sector’s peculiarities and the aim to correct market failure. It is also the result of political rent-seeking of farmers’ interest groups38. Permanent income problems of many farmers encourage producers to view it as legitimate to reach economic goals through lobbying for protectionism and direct financial support31,39. And agricultural interest groups are typically well-organised and characterised by high affiliation percentages, not least due to the fact that transaction costs for coordination are partly financed over by public funds (ibid.). Furthermore, a counterweight to homogeneous interest groups representing farmers is missing. Taxpayers and consumers are seldom organised at all, despite the emergence of new ideas affecting the agricultural policy debate (especially market liberalism, sustainability, consumer concerns) since the 1980s and the involvement of new institutions in the agricultural policy domain, which have brought new actors into the agri-food policy arenae 40,41. And even if they are organised – in consumer or green advocacy groups for example – they are usually not admitted to the core of agricultural policy networks. As a consequence, relatively little is known about the degree to which these players influence policy around food and agriculture40. It can be assumed, though, that their (indirect) involvement in the policy making process adds a layer of complexity to reaching agreements with respect to policy reforms42. The broad group of taxpayers and consumers is further only rarely aware of the functioning of agricultural policy and of the connection between taxes paid in their respective country and CAP expenditures. It is only in the last decade or so that the lobbying power of the primary farming sector, while still being strong, has begun to steadily be eroded by the views of environmental, animal welfare and health interests43.

Nedergaard31 argues that the design of the CAP is also the result of what he calls an “institutional bias towards agricultural interests within the political system” (p. 407). In addition, and making use of rational choice theory and indirectly Tullock’s44 concept of rent-seeking, he reasons that bureaucrats involved in the decision-making process concerning agricultural policy act in their own interest (career possibilities, increasing power bases etc.) and therefore prefer an agricultural policy system that is complex, technical, includes bureaucratic interventions and strong governance. He concludes that the CAP shows a certain asymmetry which is sharpened by politicians and bureaucrats who have independent reasons for fostering a complicated and protectionist agricultural policy. Protectionist elements have also been reported to be the response of politicians and officials to the demand for protective forms of regulation from farmers45. Those in authority hence “sell” regulations in exchange for political support. Acemoglu and Robinson46 show that, fearing loss of electoral support, politicians are willing to intensify their support of the interests of specific social groups, especially if they constitute a sufficiently strong electorate – which still is the case with respect to farmers in particular and the rural population in general on the European level.

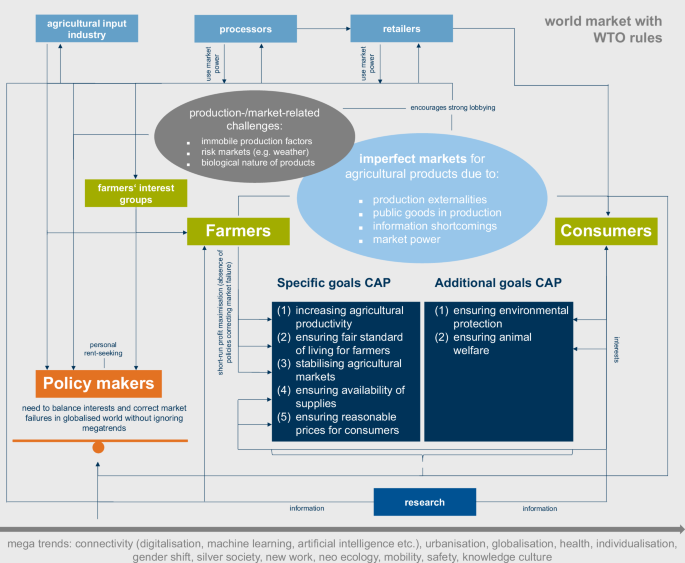

Besides these structural or “government failures” (asymmetry between farmers and consumers as regards political influence, institutional bias towards agricultural interests, utility maximising bureaucrats) – as Nedergaard31 calls the weaknesses of the political system described above – explaining the characteristics of the Common Agricultural Policy, four generally recognised classes or causes of market failures exist that also shape the CAP and that have been mentioned previously. These are externalities, public goods, insufficient information and market power. They can all be tackled through government intervention. Indeed, European agricultural policy aims at correcting market failures47. At the same time, its policy design needs to account for general CAP goals, characteristics of the agricultural sector, “government failures” described above, WTO rules that promote fair market conditions and megatrends affecting overall development. The complexity of this task including the most relevant factors is shown in Fig. 1. Daugbjerg and Feindt40 consider it to be a main reason for an ‘exceptionalist’ policy-making process in the agricultural domain. They argue that this exceptionalism attracted research interest in the field of political sciences and led to studies about interest groups, government-interest group relations, the role of ideas and paradigms in explaining policy change and stability, policy feedback and path dependency and more recently, policy layering and internationalisation of public policy. Indeed, theoretical points connected to these topics can well be illustrated with examples from agricultural policy. Some rather new developments in the food and agriculture sector – especially internationalisation of policy-making, the growing importance of self- and co-regulation, the interlinkage with other policy domains – add further concerns as regards the nature of policy-making.

The big light grey box symbolises the world market for agricultural commodities, the main players in this market are depicted in varicoloured boxes: farmers and consumers (both green), policy makers (orange), processers, retailers and the agricultural input industry (all in cyan) and research (blue). Both dark blue boxes refer to goals of the Common Agricultural Policy, whereas the ellipses in light blue and grey capture economic and production-/market-related peculiarities of the agricultural sector. All arrows show interlinkages between the players on the market, policy goals and the functioning of the agri-food system.

It is evident that designing agricultural policy in a manner that incorporates all of the aspects shown in Fig. 1 is challenging. This is also reflected in constant adjustments of both the CAP and agricultural policies on a regional level. The basis for these adjustments ideally is research that empirically captures the impact of policy measures on the micro- and the macro-level and links (expected) effects to economic theory. Thus, empirical research is required to assess how agricultural policies affect the various aspects described above, from farmers’ performance and production strategies to WTO requirements.

Figure 1 further suggests that any agricultural policy will need to balance national interests and trends (food security, cultural landscape, changes in diets, public opinion) with rules for international trade and differences in farming standards around the globe. Given that common standards on how to produce agricultural goods are not even on the horizon on a global scale, at least on the European common market such a situation is desirable. It would require a further harmonisation of national and regional agricultural frameworks and a common way of measuring farm performance, i.e. generally agreed upon, scientifically sound economic, environmental and social indicators (which could be used for food labels). In the long-run, payments could then only be granted for a proven, additional provision of environmental and social services without distorting markets for traditional agricultural goods. There will be a need to discuss, though, to what extent agriculture actually “provides” environmental services and what we understand by those48 given that agricultural production per se reduces most services compared to a non-production state. Certainly, in the absence of studies holistically contrasting ecosystem services from agriculture to the sector’s environmental impacts, this discussion needs to be more a semantic one. Following the payments-for-benefits path, farmers in less favoured areas using well-adapted extensive production systems could profit from “producing” environmental and social services, ensuring agricultural land-use and the role of agriculture in rural areas. Against the backdrop of these functions of agriculture (i.e. esp. food security in times of unstable international relations, cultural landscape), only any remaining income differences among farms caused by natural conditions would need to be offset by less favoured area support schemes. Obviously, such a situation involves a certain trade-off between an efficient use of resources and other political goals. What is more, the little empirical evidence on farm-level land use in response to and the success of less favoured area payments is mixed49,50,51,52,53, which calls for improving the design of these schemes or for innovative measures.

While the points mentioned so far are mainly connected to designing policies, their implementation is equally crucial. It is impaired by the complexity, technicality and bureaucracy that has resulted from the policy-making context. Logically, implementation costs (i.e. costs for conceptualising, implementing, monitoring and evaluating policy measures) are high. In the German federal state of Baden-Württemberg for example, the administrative costs of the CAP accounted for 13% of support paid out54 – not counting transaction costs of farmers. If the overall economic gains of the CAP are to outweigh implementation costs, the administrative process needs to be simplified dramatically55,56. One can conclude from Ehlers et al. 56, Rotz et al.57 and the European Commission58 that this involves unifying the Integrated Administration and Control System (ICAS) as well as the corresponding portals for farmers while allowing flexibility for different agricultural contexts to be captured, creating a thorough legal framework for each funding period and increasing the use of digital technologies. Digital improvement of the system as well as the use of remote sensing data and artificial intelligence is important as it could reduce the administrative burden for authorities and farmers (and thus transaction costs) by setting up interfaces to farm management software and integrating tools for farm-level reporting (e.g. nutrient management, livestock database). These potential benefits of the integration of a logic of big data into governance can only be enjoyed, though, if the developed and connected tools make sense for the practitioners (giving them empowerment and countering the rationales of bureaucratisation), which involves rethinking what kind of data are collected and how they can create more value for the farmers themselves59. Perceived added value will also depend, as in other areas of digitisation, on answers to questions of data protection and an equitable sharing of access to data and of data usage. So far, these answers are rather unsatisfactory57. What is more, a successful digital transformation of agricultural governance requires dynamic agricultural authorities that are able to attract IT experts60 or to buy in relevant IT services. Implementation costs might further decrease by reducing the complexity of policy-making in the agricultural domain through setting priorities based on scientific findings and communicating these to producers and consumers.

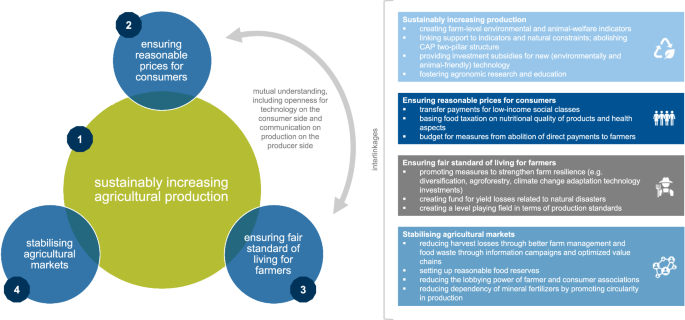

Such a goal prioritisation and necessary action plans taking into account all specifics of the agricultural sector are depicted in Fig. 2. It has to be interpreted bearing in mind the overall CAP goals and current CAP key objectivesf, some of which seem to contradict each other61. In the light of conflicting goals and budget constraints, any prioritisation thus also reflects shifting societal needs. Against the background of current scientific findings, the main aim of future agricultural policies should be sustainably increasing production. Connected to and backing this goal are the subjects 2-4. Generally, there is a large degree of overlap between the areas, so that measures to sustainably increase the agricultural output will positively influence the sub-themes via market reactions and vice versa. Putting different weights on the importance of the four domains can be expected to guide policy makers in setting agendas and can prevent the emergence of phoney debates.

The figure suggests a new framework for the Common Agricultural Policy. It is derived from and tries to merge findings from the scientific literature, agricultural practice and societal demands. A goal prioritisation is proposed (numbers 1–4) with the boxes on the right-hand side explaining how each goal can be reached.

Overall, any new policies will need to be backed by evidence-based research in order to improve acceptability, efficiency and effectiveness62. They will also need to better integrate societal demands if farmers are to be less of bogeymen63,64. In a similar manner and more than ever, research approaches must be interdisciplinary and comprehensive. Both in the political and in the academic sphere, more collaboration, communication and coordination is needed across different disciplines, but also with key actors of the agri-food sector, to which producers and consumers equally belong65. This will facilitate mutual understanding as regards the complexity behind agricultural policy-making and will help in reconciling economic, social and environmental goals. For each party involved in this process, and especially for farmers’ associations, which have been rather reactive until now, this requires openness and innovative capability – and sensing opportunities rather than challenges only.

Concluding remarks

The Common Agricultural Policy remains a contentious and complex framework, reflecting the multifaceted challenges of modern agriculture in Europe. It is not only shaped by the unique economic characteristics of the agricultural sector, but also by significant political influences and institutional biases within the political system. Despite multiple reforms, the CAP continues to face criticism from various quarters: farmers lament the restrictive regulations and insufficient economic support, while environmental advocates argue that the policy does not go far enough in addressing ecological concerns.

This short article underscores the necessity of a holistic approach to CAP reforms, integrating insights from political science, economics, agronomy, and environmental science. It highlights the importance of prioritising objectives within the CAP to ensure a more focused and effective policy-making process. The key to successful reform arguably lies in enhancing collaboration, communication, and coordination among all stakeholders, including policymakers, farmers, environmental groups, and consumers. Additionally, a greater emphasis on empirical, interdisciplinary evidence is needed to evaluate the impacts of policy interventions accurately.

Future CAP reforms should strive to balance the diverse and sometimes conflicting goals of economic viability, environmental sustainability, and social welfare. This requires a concerted effort to streamline administrative processes, reduce bureaucratic burdens, and leverage digital technologies for more efficient policy implementation. Moreover, policies must be underpinned by robust scientific research to improve their acceptability, efficiency, and effectiveness.

In conclusion, the CAP’s ongoing evolution will benefit from a more integrated and adaptive approach, capable of responding to the dynamic needs of the agricultural sector and society at large. By fostering a deeper understanding of the complex interdependencies within agricultural policy-making and embracing innovation, the CAP can better fulfil its role in supporting sustainable and resilient agriculture in Europe.

Responses