A personalised and comprehensive approach is required to suppress or replenish SNCA for Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

Alpha-synuclein (α-Syn), encoded by the SNCA gene, has been linked to Parkinson’s disease (PD) since 1997 when the first pathogenic missense mutation (A53T) was identified. Since then, many other SNCA mutations, including gene duplication and triplication in some familial cases have confirmed the determinant role of this gene in PD1,2,3. Over two decades of efforts have been elucidating the physiological functions of α-Syn in synaptic vesicle exocytosis, endocytosis, dopamine release, and innate immune defence4,5,6; however, the underlying mechanisms of how α-Syn mutants cause the disease are yet to be fully uncovered. Predominantly known as a “natively unfolded and intrinsically disordered” monomer, physiological α-Syn is enriched in the presynaptic nerve terminals and participates in synaptic neurotransmission. This protein is highly dynamic and can adapt to several conformational changes of which the functional consequences are modulated by several factors including its variant β-Syn that has been shown to act as either an anti-aggregation agent against α-Syn or an amyloidogenic protein7.

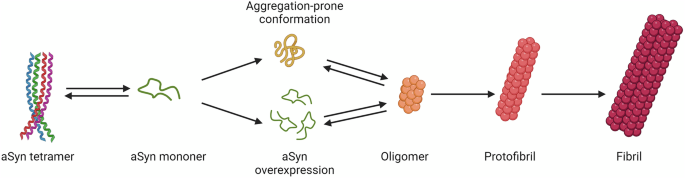

In addition, α-Syn co-exists in an equilibrium of monomers and multimers, including tetramers8 (Fig. 1), which adopt an α-helical membrane-bound structure and facilitate its functions in synaptic neurotransmission and in exocytosis and vesicle turnover9. Compared to aggregation-prone monomeric forms, α-Syn tetramers exhibit little or no amyloid-like aggregation potential10. Familial PD-causing mutations have been shown to destabilise α-Syn tetramers and decrease the ratio between tetramer and monomer, which is thought to initiate PD pathogenesis11,12. In addition, SNCA missense mutations were found to cause misfolding of the protein and generate “toxic” α-Syn species. Thus, prevailing research focus has been on the “gain-of-function” and the toxicity of the pathological α-Syn species. However, emerging evidence indicates that the loss of physiological functions of the α-Syn protein, which is sequestered into α-Syn aggregates may contribute to PD pathogenesis. In this paper, we will discuss evidence supporting both α-Syn “gain-of-function” and “loss-of-function” hypotheses and provide our perspective on developing personalized and comprehensive therapeutic approaches targeting α-Syn.

Missense mutations that make α-Syn aggregation-prone, or SNCA duplication or triplication, or polymorphisms that increase the expression of monomeric α-Syn facilitate the formation of toxic soluble oligomers which elongate into protofibrils and fibrils. Image modified from Richard Smith et.al. European Journal of Neurology 2023101.

α-Syn “gain-of-function” hypothesis

A “gain-of-function” hypothesis is supported by the findings in both familial and sporadic cases of the hallmark Lewy body pathology, which largely comprises α-Syn aggregates with a plethora of non-proteinaceous components including lipids, nucleic acids, and degraded cellular structures13. As the main Lewy body component, α-Syn aggregates are considered to be initiated by the misfolding and accumulation of phosphorylated α-Syn, which was found to be enhanced by SNCA missense mutations14, as shown in Fig. 1. While genetic overexpression of the wild-type α-Syn as a result of SNCA gene multiplications, expansions of the Rep-1 polymorphism in the promoter region, genetic variants in the 3′-untranslated region15,16, or intronic polymorphisms of the gene17 was believed to disrupt the synthesis-clearance balance18, resulting in accumulation of the protein and formation of abnormal oligomeric and fibrillar α-Syn species that have been assumed to have a toxic dose effect19.

However, the regulation of SNCA expression by these polymorphisms may be different in brain regions or even in different neuronal subpopulations15. As seen in Table 1, the complex correlations between SNCA expression and SNCA genotypes may require further investigations in larger cohorts to clarify its underlying disease mechanisms. In an observational study of over 1,000 PD patients, Rep-1 genotypes that were initially identified as increasing risk of PD via an increased SNCA expression were in fact found to associate with better motor and cognitive outcomes than genotypes associated with lower SNCA expression20. In addition, the lack of PD clinical symptoms or prodromal features was unexpectedly found in some aged individuals (over 61 yrs of age) with a SNCA duplication21, which generally leads to disease onset at a mean age of 46.9 or 34.5 in cohorts carrying heterozygous or homozygous SNCA duplications22.

α-Syn conformers, including soluble α-Syn oligomers and insoluble fibrils have been considered to be “toxic” through damaging mitochondria, disrupting axonal transport, compromising microtubular function, and triggering lysosomal leakage; and have been shown to propagate disease pathology and neurodegeneration in PD animal models23. The accumulation of presynaptic α-Syn oligomers has been visualized in patient brains with dementia with Lewy bodies, another synucleinopathy, and has been hypothesized to cause synaptic dysfunctions24. However, it should be emphasised that, as in the case of the proposed role of “toxic oligomers” of amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease, the concept of α-Syn oligomer toxicity in PD has not yet been fully supported by human studies or conclusively proven in experimental animal models at a physiological level of the SNCA gene or the α-Syn protein. Nor has evidence of toxicity been found with any types of dopamine-induced α-Syn oligomers in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells or in isolated rat synaptosomes25. Intriguingly, within the conformationally heterogenous α-Syn pool, a subtype of fibril-rich and pS129-positive α-Syn aggregates was recently found to be neuroprotective by detoxifying a lipid-rich class of highly dynamic α-Syn inclusions26. The findings from rapid and scalable iPSC inclusionopathy models may shed light on the molecular subtypes and functional consequences of α-Syn aggregates, however further investigations are needed in more intricate disease modelling systems.

Nevertheless, the “gain-of-function” hypothesis has been leading the majority of therapeutic developments to reduce the levels of α-Syn or remove α-Syn aggregates. Some of those approaches have demonstrated both the ability to clear established Lewy body pathology and to prevent dopaminergic neuron dysfunctions27. However, suppressing α-Syn has recently been challenged, following negative results of the first two Phase 2 clinical trials of monoclonal antibodies targeting the N and C termini of α-Syn28,29. Possible pitfalls, including improper study design or execution, failure to enrol the most suitable patients, incorrect drug dosage, or insufficient understanding of disease mechanisms have been discussed as possible factors leading to failed clinical trials30. These initial unsuccessful outcomes should not, however, necessarily impact the further development of anti-Syn therapies; but may instead serve to prompt a redefinition of the concept of a α-Syn “gain-of-function” hypothesis so as to develop effective therapeutic strategies. In fact, in a more recent publication by Pagano et. al., results of the clinical trial of Prasinezumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting aggregated α-Syn, demonstrated some level of symptomatic benefits in a subgroup of PD patients with a more rapidly progressive disease phenotype31. It will be interesting to further investigate the underlying factors that lead to a faster disease progression and a more favourable response to lowering α-Syn aggregates.

Gain-of-function caused by genetic mutations refers to new or enhanced activity, or increased expression of a protein resulting from genetic variants. Thus, the term “gain-of-function” may be appropriate when applied to SNCA multiplications or genetic variants in the 5′ or 3′ UTR or intronic regions, where gene dosage is increased or transcription is enhanced and there is demonstrable overexpression of normal α-Syn protein32 as shown in some cases in Table 1. However, known SNCA missense mutations, including A53T, A30P, E46K, and A53E have minimal effects on the transcription or translation of SNCA. Rather, these point mutations tend to alter the protein structure and its biochemical properties, making it more susceptible to aggregation and leading to the generation of “toxic” α-Syn species. Therefore, SNCA point mutations may contribute to PD in a “toxic gain-of-function” manner, or in combination with a “loss of function” resulting from depletion of the physiological form of the protein. This may also occur as a result of haploinsufficiency as found in familial PD cases carrying the A53T and A30P SNCA mutations33,34.

Emerging evidence pointing to α-Syn “loss-of-function”

Emerging lines of evidence including the poor correlation between Lewy body pathology (including Braak staging) and disease severity and duration35,36 have questioned the “gain-of-function” hypothesis and have drawn attention to the possibility that α-Syn “loss-of-function” could contribute to PD pathogenesis37. Notwithstanding a few post-mortem studies that have reported an increased expression of α-Syn protein or mRNA in small numbers of PD brains38,39,40, many more investigations have demonstrated significantly reduced levels of α-Syn41,42,43,44,45,46,47 in sporadic PD brains. Although insoluble α-Syn species accumulate over the course of the disease; reduced levels of soluble α-Syn have been found in PD-vulnerable brain regions23, which subsequently results in a reduction of its levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and in venous blood as has been shown in a series of investigations in both sporadic48,49,50,51,52 and SNCA duplication patients53. The latter finding is intriguing as an increased gene dosage would normally be thought to correlate with more protein production. This controversial finding may be attributed to the challenges in measuring the steady state level of soluble α-Syn because of its variable half-life, ranging from a few hours to over 2 weeks54 as reported using different experimental approaches, and the half-life being significantly reduced under an overexpression condition55.

Nevertheless, as argued in a recent review, overexpression of the protein may lead to supersaturation, lowering the nucleation barrier for the soluble-to-insoluble phase transformation of soluble monomeric α-Syn to Lewy pathology, reducing the levels of soluble α-Syn in the brain and CSF56. Therefore, genetic overexpression does not necessarily cause a “gain-of-function” and may actually be compatible with a “loss-of-function”. It has recently been argued that depletion of the functional monomeric or tetrameric forms of α-Syn could essentially play a more important role than the Lewy body pathology in the neurodegenerative process57,58. Similar findings have also been reported in prion disease and polyglutamine disorders where normal cellular functions are compromised because of the sequestration of physiological proteins into non-functional aggregates59.

The pathologic accumulation of α-Syn is not associated with any significant increase in expression of the protein which instead generally results in depressed expression levels while the disease progresses60. This is supported by recent post-mortem RNAscope data demonstrating that SNCA transcription that is preserved in early disease stages in the substantia nigra neurons is gradually reduced during Lewy body formation and disease progression61, which is in line with previous investigations47,62. In addition to these findings in human brain tissues63, decreased levels of endogenous soluble somatic and nuclear α-Syn were also detected after the intracerebral introduction of pre-formed α-Syn fibrils (PFFs), which in mouse models act as a seed for the accumulation and aggregation of wild-type α-Syn. Minimum levels of synaptic and soluble α-Syn are found after the administration of α-Syn PFFs, indicating that physiologically functional α-Syn is sequestered and diminished during the aggregation process8,64. Although α-Syn fibrils, or possibly the intermediate α-Syn oligomers could result in the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons observed in these a-Syn PFF models, the diminished levels of endogenous functional α-Syn could also play a contributory role due to the loss of its physiological activities including but not limited to protecting dopaminergic neurons from damage induced by noxious cellular stimuli65.

However, these experimental observations need to be interpreted with caution, as in some rodent and non-human primate α-Syn PFF models, SNCA knockdown with antisense oligonucleotides was found to prevent dopaminergic cell dysfunction27 or reduce the regional spread of phosphorated α-Syn (pS129) pathologies66. Evaluations of motor functions in these SNCA-lowered mice will, however, be required to confirm any therapeutic effects following the reduction of pS129 α-Syn, a surrogate marker of pathology, which can also be physiologically triggered by neuronal activities67. Thus, caution is needed in interpreting changes in the levels of pS129 or α-Syn aggregates, which are generally labelled by pS129, without distinguishing its physiological and pathological forms. Interestingly, a naturally occurring high abundance of pS129 has been reported in some brain regions68 and an up to threefold variation in pS129 levels can occur as a result of neuronal activities to positively regulate synaptic transmission69. Furthermore, one subtype of pS129-postive α-Syn aggregate was recently found to be neuroprotective in iPSC models26.

Other intriguing experimental data has shown a significant loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons in adult rats following α-Syn suppression by the injection of siRNAs and the extent of neuronal loss was correlated with the degree of α-Syn depletion in a dose-dependent manner70. In addition, a region-specific, tier-related degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons and striatal innervation was demonstrated in non-human primates treated with short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) targeting SNCA37,71. Although these studies involved relatively small numbers of animals and presented limited data, their results may have suggested that adequate levels of functional α-Syn are required for neuronal survival; and it is noteworthy that neurodegeneration was rescued by replenishing normal α-Syn in one of those studies70. Similar outcomes were demonstrated in adult rats receiving shRNA targeting SNCA, where α-Syn knockdown resulted in a 50% loss of nigrostriatal neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, a loss of nigrostriatal terminals, and a depletion of dopamine within the striatum72. However, the use of AAV vectors, and the loss of the antimicrobial (anti-viral) activity of α-Syn and of effects on innate immune responses because of its depletion, were possible confounding factors in those studies and could have contributed to the neuronal loss73,74,75. Indeed, the depletion of functional α-Syn was shown to initiate a neuronal-mediated inflammatory cascade, involving both innate and adaptive immunity, which resulted in the death of affected neurons in PD models72,76.

In a recent population-scale analysis of rare SNCA variants, one participant with a SNCA whole gene deletion demonstrated PD prodromal features at the age of 5421. While the other five SNCA deletion cases were symptom-free at an average age of 51, whether they would develop the disease warrants follow-up investigations21. Although aging is a key risk factor for developing PD, it is noteworthy that studies in both humans and monkeys have shown that cytosolic levels of α-Syn in nigral dopamine neurons do not fall, but actually increase with aging77, possibly representing a compensatory mechanism against aging-related neuronal death. Whether neurodegeneration is initiated by manipulating SNCA levels may depend on the levels of functional α-Syn as discussed elsewhere8. Although the minimum level of α-Syn required to maintain its physiological synaptic functions is still undetermined, it has been suggested that neurodegeneration may start to occur when α-Syn levels fall below a threshold of ~30%8, with recent evidence showing that no neurodegeneration or motor dysfunctions were noted after ~68% α-Syn knockdown66.

Therefore, restoring the levels of soluble and physiologically functional α-Syn might be beneficial in those having less than 30% of physiological α-Syn protein; meanwhile, considerations could be given to first validating the efficacy of such an approach in experimental disease models. However, as proposed elsewhere, most animal models while useful to evaluate molecular mechanism, drug toxicity, and safety, could be unreliable or misleading to test such a disease hypothesis or to validate therapeutic efficacy of certain compounds, as witnessed by the poor correlation between animal model based-success and clinical trial-success78. Moreover, possible detrimental effects of supplementing an excess of monomeric α-Syn without knowing what the baseline levels are in individual PD patients also need to be considered and could conceivably increase α-Syn aggregation and fibril formation. It has been shown that at high concentrations monomeric α-Syn undergoes a liquid-to-gel phase transition, which can act as a reservoir of trapped α-Syn oligomers and fibrils79.

Personalized and comprehensive strategies

Based on the current state of knowledge and the complexity of PD at a genetic and molecular level80, a biological classification based on the presence or absence of pathological α-Syn, as well as SNCA genotypes, and biochemical phenotypes81 will be essential for PD diagnostics and precision drug development. Further to the application of a biological definition of α-Syn in PD disease staging82, we believe a biological or biochemical definition of α-Syn at a personalised level will be the key to the discovery of novel therapies targeting underlying pathogenesis in a precision medicine manner83. Therefore, it is likely, as outlined below that distinct but comprehensive approaches will be needed for different subgroups of patients carrying distinct SNCA mutations or disease-modifying alleles, or with different SNCA biochemical phenotypes (Table 1).

-

1.

Although such cases are rare, proof-of-principle verification of the efficacy of α-Syn suppression strategies could begin in patients with SNCA gene multiplications with increased α-Syn levels41, in whom reducing levels of endogenous α-Syn would intuitively make sense. However, the level of soluble α-Syn in CSF, or ideally in the brain may need to be checked for each individual patient before α-Syn is reduced by any means. As previously indicated, an increased gene copy number does not necessarily increase its protein expression and low CSF levels of α-Syn have been reported in SNCA duplication patients53. It follows that the finding of a low level of α-Syn in the CSF would be considered as an indication for α-Syn replacement rather than α-Syn suppression therapy.

-

2.

Similarly, PD patients with disease-modifying SNCA polymorphisms, including expanded Rep-1 alleles, genetic variants in the 3′-untranslated region, and intronic polymorphisms, would be the second patient subset in which anti-α-Syn treatment might be considered, provided that evidence of increased α-Syn expression is demonstrated.

-

3.

On the other hand, as decreased levels of soluble α-Syn has been demonstrated in post-mortem studies in familial PD with the SNCA A53T and A30P mutations84, it may be beneficial to restore levels of monomeric α-Syn in such cases. There is a scarcity of studies exploring the levels of soluble α-Syn in patients carrying other SNCA missense mutations including A30G, E46K, H50Q, G51D, A53E, and A53V. However, since these mutations were found to contribute to α-Syn pathology by altering α-Syn phosphorylation or interfering with specific steps during α-Syn aggregation, it may still be likely that soluble α-Syn is depleted and that further reducing α-Syn levels could exacerbate neurodegeneration.

Because of the rarity of such cases and of SNCA gene multiplications, these strategies would have to be trialled at a later stage through the orphan drug approaches rather than the conventional randomised clinical trials, once decisions have been made as to the appropriate therapeutics and at what stage of the disease to administer them. It is likely that such proof-of-principle assessment of therapeutic approaches in these forms of genetic PD would be more likely to succeed if performed in an early disease stage or even in the prodromal stage in cases with high-penetrance mutations.

-

4.

For the majority of patients with other monogenic forms of PD who are associated with α-Syn pathology and with idiopathic PD, further systematic and comprehensive investigations are required to elucidate the dominant underlying molecular mechanisms and whether levels of functional α-Syn are depleted or raised in relation to an established normal range, before deciding whether α-Syn suppression or replacement is more appropriate. Bearing in mind that any constituent in the human body should be within a certain range and α-Syn may have dual and opposing roles in the disease15.

Future perspectives

Parkinson’s disease is a complicated disorder driven by multiple processes rather than by a single protein, even in those rare cases with a SNCA mutation. Therefore, comprehensive therapeutic strategies are likely to be required in parallel with a personalized approach to either suppress or replenish α-Syn to a certain level required to implement its critical functions. The removal of α-Syn fibrils could potentially restore the levels of functional α-Syn by reducing the seeding of monomers; however, it might possibly result in the production of “toxic” intermediate pre-fibril α-Syn oligomers, which are thought to exist in equilibrium with monomeric α-Syn and to undergo slow conversion to fibrils19. Crucially, the initiating factors mediating conformational changes in endogenous α-Syn, or more importantly for wild-type monomeric α-Syn to oligomerize and to form fibrils, or factors involved in phase transition of soluble proteins into insoluble amyloids85 need to be better and fully understood.

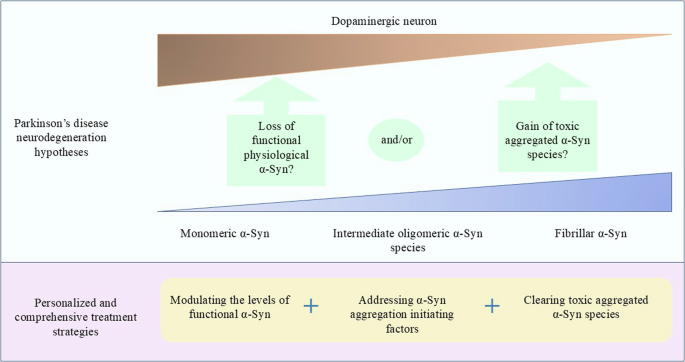

In light of the complexity and heterogeneity of PD, our perception is therefore that the ideal disease-modifying strategy should comprise a combination of personalized approaches. These (Fig. 2) include maintaining physiological α-Syn levels, removing toxic α-Syn conformers, clearing α-Syn seeding fibrils, and addressing α-Syn aggregation initiating factors, which are likely to include post-translational modifications in α-Syn and as yet unknown modifications in the cellular milieu. Additionally, potential therapeutic targets should also include the endolysosomal pathway, mitochondrial function, neuroinflammation, and glucose and lipid metabolism, all of which may contribute to PD pathogenesis individually or synergistically, with or without α-Syn.

The questions over whether α-Syn “loss-of-function” or “gain-of-function” or a combination of both contributes to PD still need to be resolved. It is proposed that a comprehensive approach including fine-tuning monomeric α-Syn levels by either reducing or increasing its level, addressing the underlying mechanisms involved in α-Syn accumulation and aggregation, and removing toxic α-Syn is likely to be required.

Alternatively, disease-modifying strategies could focus on stabilising α-Syn tetramer by using small molecules or modulating the levels of PD related genes, including LRRK2 and GBA1 which has been shown to increase the α-Syn tetramer : monomer ratio, improve lysosomal integrity, and attenuate motor and cognitive functions in PD mouse models86,87. However, further investigations are required to elucidate the mechanisms of how these PD-linked genes participate in α-Syn dysregulation. The reduction of GCase protein and the loss of GCase enzyme activity caused by GBA1 mutations are believed to cause α-Syn to aggregate and subsequently form Lewy body pathology; however, the “gain-of-function” hypothesis due to enzyme misfolding is also considered as an important contributor to the disease. Postmortem studies have shown the presence of Lewy body pathology in patients carrying GBA1 variants, however the degree of the pathology varies88. Diverse pathological findings have also been found in LRRK2-PD. For example, the typical a-Syn pathology was found in some G2019S cases, the most common LRRK2 mutation; while the absence of Lewy pathology has been related to other mutations including R1441H, R1441G, and I2020T89,90,91. In addition, the classic synucleinopathy was less frequently found in autosomal recessive PD cases especially those carrying PARK2 mutations92,93, which, however, may be due to the paucity of human data or caused by distinct disease mechanisms94.

Nevertheless, huge gaps must be filled before viable therapies will reach patients. These include but are not limited to the identification of dominant toxic α-Syn species, mechanisms of α-Syn aggregation and oligomerization, precise animal models to provide proof-of-concept, and reliable biomarkers for use in well-designed clinical trials in patient cohorts that have undergone careful clinical and biochemical phenotyping and genotypic evaluations. Furthermore, the development of accurate and sensitive techniques to monitor levels of physiologically functional α-Syn will be essential to determine which SNCA patients are suitable for either SNCA suppression or replacement therapy and will be a key monitor in clinical trials.

The α-Syn seed amplification assay (SAA) has been developed to detect α-Syn seeds in CSF or blood samples and has shown huge potential in diagnosing PD and differentiating PD from other synucleinopathies95,96. Although negative results were reported in certain PD subpopulations including normosmic PD or LRRK2-PD96,97, which was proposed to have distinct disease patho-mechanisms, SAA would be a promising tool to monitor treatment strategies that reduce α-Syn seeding aggregates. Other methods, including single-molecular ELISA98, nanopore detection system combined with molecular carriers99, and molecular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology100 have also shown some promise in detecting oligomeric α-Syn in different sample types. The development of such tools to accurately quantify the levels of monomeric α-Syn would be critical to test the disease hypotheses and to select the right patient groups for the future clinical trials.

Getting the right treatment for PD is challenging; however, we are optimistic that continued investigations of therapeutic approaches targeting α-Syn and adopting a personalised, yet comprehensive approach will ultimately lead to an improved quality of life for people with PD.

Responses