A polyene macrolide targeting phospholipids in the fungal cell membrane

Main

Infectious diseases caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) fungal pathogens pose a serious threat to human health, particularly with the increase in the number of people with immunocompromised conditions and the overuse of antifungal antibiotics in agriculture, animal husbandry and clinical settings3. The worldwide emergence of MDR Candida auris is a serious concern, which in some instances is resistant to all four primary classes of antifungal medication (that is, polyenes, azoles, echinocandins and the pyrimidine analogue 5-flucytosine)4, resulting in high mortality and persistent transmission. Centuries of experience in addressing microbial infections have shown that discovering antibiotics with unique modes of action is the most effective approach in combatting resistant pathogens5. Nevertheless, the pursuit of previously unknown antifungals faces challenges arising from the scarcity of identified antifungal targets and the reduced efficiency of the conventional activity-guided antifungal drug-discovery strategy2. These challenges prompt the application of innovative strategies for discovering antifungal agents with unique modes of action to combat MDR fungal pathogens.

Microbial secondary metabolites have historically been rich sources of antimicrobial compounds, with over 70% of clinically used antibiotics being microbial secondary metabolites and their derivatives6,7. During dynamic intraspecific competition in nature, the genes responsible for antibiotic production, such as those encoding potent antibiotics, may have evolved continuously, enabling microorganisms to overcome antibiotic-resistance challenges and ensuring their survival in ecological niches. The evolution of genes involved in antibiotic biosynthesis may give rise to enhanced antibiotics with diverse structures and distinct modes of action. The concept of antibiotic evolution has been applied in previous endeavours to address MDR bacterial infections, leading to the discovery of macolacin8, cilagicin9 and corbomycin10.

To discover antifungals with previously undescribed modes of action against MDR fungal infections, we implemented a phylogeny-guided natural-product discovery strategy, focusing on the polyene macrolide family of antibiotics. This family was chosen for its diverse structures, potent and broad-spectrum antifungal activity and low likelihood of resistance development. The structures of clinically used polyene macrolide antibiotics feature an amino deoxy sugar, mycosamine—an evolutionarily preserved motif that is key to the antifungal activity of the compounds. Thus, to facilitate the discovery of polyene macrolide antibiotics, we constructed a phylogenetic tree of glycosyltransferases responsible for transferring mycosamine onto the macrolide skeleton. Our efforts led to the identification of a promising antifungal candidate, mandimycin, biosynthesized by the mand gene cluster of an orphan clade. Mandimycin displays potent and broad-spectrum fungicidal activity against various MDR fungal pathogens in both in vitro and in vivo experiments. In contrast to reported polyene macrolide antifungals that target ergosterol, mandimycin uses a previously undescribed mode of action by targeting various phospholipids in the fungal cell membrane, while also exhibiting reduced nephrotoxicity and increased aqueous solubility compared with amphotericin B, the clinically used polyene antifungal drug.

Discovery of mandimycin

To discover antifungal polyene macrolide antibiotics with unique modes of action from microbial resources, we have curated a vast collection of 316,123 bacterial genomes from the National Center for Biotechnology Information as well as 150 Streptomyces genomes sequenced in our laboratory. Identification and annotation of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) were performed for these compiled genomic sequences using the antibiotics and Secondary Metabolites Analysis Shell (antiSMASH)11,12. This analysis led to the identification of 1.78 million BGCs predicted to encode various types of secondary metabolite. The predicted BGCs were then integrated in a localized microbial secondary metabolite (MiSM) database and served as a searching platform designed specifically for the exploration of BGCs encoding mycosamine-containing polyene macrolide antibiotics.

In our phylogeny-guided screening efforts, glycosyltransferases responsible for transferring mycosamine onto the polyene macrolide ring were chosen as the sequence tag13,14 (Extended Data Fig. 1a). We developed a profile hidden Markov model using 11 mycosamine-transferring glycosyltransferases characterized by reported polyene antifungal BGCs (Supplementary Table 1) and systematically scanned it against the localized MiSM database for putative mycosamine-transferring glycosyltransferases. Sequences with an e value less than 1 × 10−181 were considered candidate hits, predicting a function involving the transfer of a mycosamine substrate (Extended Data Fig. 1b). The putative BGCs containing the candidate glycosyltransferases were predicted and annotated. This led to the identification of 280 unique candidate BGCs, the majority of which were previously unreported. Detailed BGC analysis revealed that the secondary metabolites encoded by those BGCs are likely to be polyene macrolide antibiotics. This is supported by the presence of core megasynthases (that is, polyketide synthases), which contain multiple dehydratase domains predicted to generate highly conjugated double bonds in the encoded products. We hypothesized that the phylogeny of the conserved mycosamine-transferring glycosyltransferases can reflect the evolution of polyene macrolide antibiotics. Identifying glycosyltransferase clades that do not cluster with those found in BGCs of known polyene macrolide antibiotics presents an opportunity to discover antifungal candidates with diverse chemical structures and previously undescribed modes of action10,15,16. To this end, we constructed a phylogenetic tree using the glycosyltransferase sequences of the 280 candidate BGCs (Extended Data Fig. 1c). The tree revealed several clades that had not previously been known to include producers of polyene macrolide antibiotics, indicating the existence of undiscovered mycosamine-containing polyene macrolide antibiotics in nature. An orphan clade that is not associated with any known characterized polyene macrolide antibiotics is of particular interest to us. In this clade, the representative BGC originating from Streptomyces netropsis DSM 40259, referred to as mand BGC, was selected for in-depth investigation (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

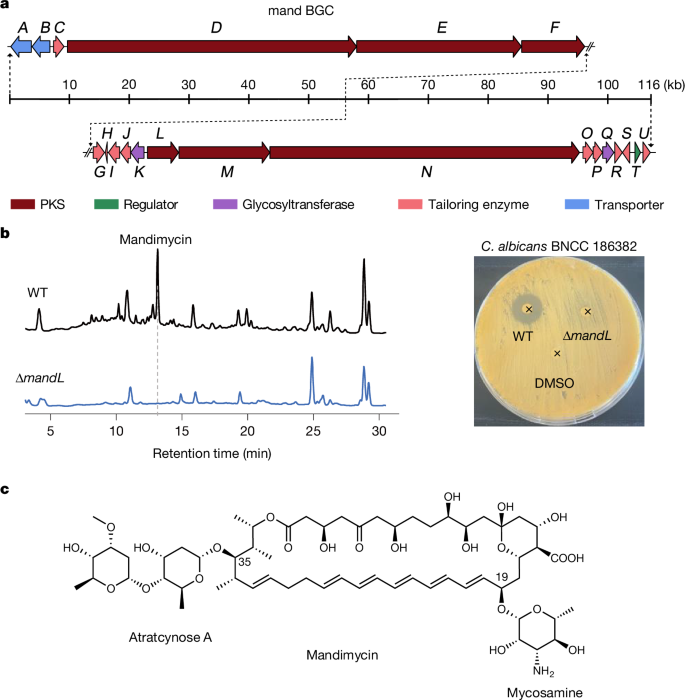

Gene annotation of the mand BGC revealed six genes (mandD, mandE, mandF, mandL, mandM and mandN) encoding polyketide synthases comprising 19 modules, predicted to encode a 38-membered macrolactone ring (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, two glycosyltransferase genes (mandK and mandQ) predicted to transfer deoxy sugars were found in the gene cluster (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). To obtain the secondary metabolites encoded by the mand BGC, we cultivated S. netropsis DSM 40259 using different fermentation media. Subsequently, high-performance liquid chromatography analysis of the culture extract revealed a major peak with a diagnostic ultraviolet (UV) absorption for the polyene moiety (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2). To establish the correlation between the mand BGC and the putative polyene chromatographic peak, we abolished the expression of the mand BGC by knocking out a 692-bp nucleotide sequence in the polyketide synthase gene mandL (Supplementary Fig. 3). This resulted in the elimination of both the polyene product and the antifungal activity of the extract, conclusively demonstrating that the mand BGC encodes the antifungal polyene secondary metabolite (Fig. 1b). Subsequently, the polyene was identified as a previously unknown pentaene macrolide antifungal compound, named mandimycin, with molecular ions at 1,198.6344 [M + H]+ and 1,196.6228 [M − H]− (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2). Further structural elucidation, including high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI–MS), two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and bioinformatic prediction, unequivocally confirmed the unique structure of mandimycin (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 2, 4–10 and Supplementary Table 3). Mandimycin represents a distinct 38-membered glycosylated polyene macrolide natural product. Its structure features a unique C-20 pentaene and C-32 monoene, differentiating it from all known 38-membered polyene macrolide antibiotics (for example, amphotericin B, nystatin and candicidin) (Supplementary Fig. 11). Notably, mandimycin undergoes unprecedented glycosylation with three deoxy sugars, including the conserved mycosamine attached to the C-19 position and a rare dideoxysaccharide atratcynose A (α-l-oleandropyranosoyl-(1 → 4)-β-d-digitoxopyranoside) linked to the C-35 position of the polyene macrolide skeleton. These features distinguish mandimycin as the polyene macrolide natural product with the highest number of deoxy sugars reported so far. This exceptional saccharide-rich structure imparts mandimycin with significantly improved aqueous solubility (around 8.07 mg ml−1), surpassing that of amphotericin B by more than 9,700 times (Supplementary Fig. 12). This characteristic of mandimycin overcomes the prevalent limitations of polyene antifungals, that is, poor water solubility and low bioavailability17.

a, BGC of mandimycin. b, Comparative high-performance liquid chromatography chromatograms of n-butanol extracts of wild-type (WT) S. netropsis DSM 40259 and the mandL-knockout mutant (left), accompanied by an agar diffusion assay of the extracts against C. albicans BNCC 186382 (right). (The locations of the added extracts are indicated by x symbols). c, The chemical structure of mandimycin determined by HR-ESI–MS, one-dimensional and two-dimensional NMR and bioinformatic prediction. PKS, polyketide synthase.

Antimicrobial activities

To investigate the antifungal efficacy and spectrum of mandimycin, we conducted microbroth susceptibility tests against a panel of priority fungal pathogens recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO)18, by following the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines19 (Supplementary Table 4). All selected fungal pathogens were resistant to two to four antifungal drugs, including caspofungin, fluconazole, terbinafine and 5-fluorocytosine (Extended Data Table 1). Our study demonstrated that mandimycin exhibited potent and broad-spectrum activity against all tested MDR fungal pathogens, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) ranging from 0.125 to 2 μg ml−1 (Table 1).

Among the tested fungal pathogens, Candida is the leading cause of invasive candidiasis globally, leading to life-threatening infections in immunocompromised patients, with mortality rates exceeding 50% despite treatment20,21. Mandimycin showed potent activity against all Candida species listed in the WHO priority list for MDR fungi, with MICs of 0.25–2 μg ml−1. Furthermore, it demonstrated substantial activity against Cryptococcus neoformans, a major pathogen causing cryptococcus infections22, with a MIC of 0.125 μg ml−1. Mandimycin also maintained potent activity against the difficult-to-treat Aspergillus fumigatus, a ubiquitous mould causing invasive aspergillosis and recognized as a critical pathogen by the WHO18, with a MIC of 2 μg ml−1. In addition to its antifungal activity, we also assessed the efficacy of mandimycin against common ESKAPE pathogens in hospitals (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter species) (Supplementary Table 5). However, mandimycin did not exhibit any bactericidal activity against Gram-positive or Gram-negative pathogens. This difference in efficacy against bacteria and fungi suggested that mandimycin uses a mechanism beyond simple cell lysis to eliminate pathogens.

Resistance and mode of action

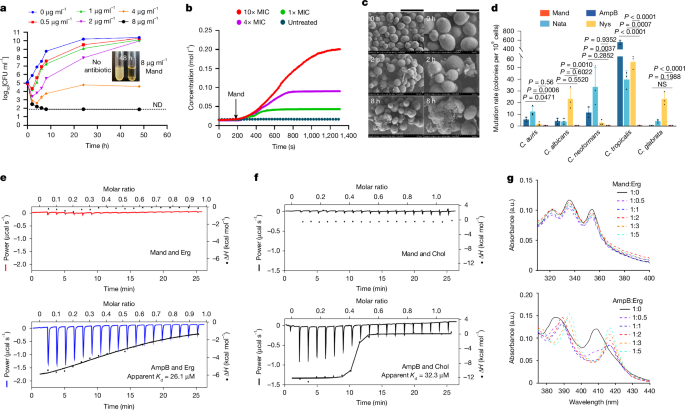

The unique chemical structure and evolutionary divergence from known polyene macrolide antibiotics prompted our interest in investigating the mode of action of mandimycin. In the mechanism study, we selected the well-characterized Candida albicans BNCC 186382 as the model strain. In the time–kill curve analysis, we demonstrated that mandimycin is a fungicidal antibiotic, capable of reducing organism burden by over more than 2 log10-transformed colony-forming units (CFU) per ml after 4 h of treatment (Fig. 2a). Next, we evaluated the impact of mandimycin on fungal cell membrane integrity by measuring the concentration of intercellular potassium ions. Our observations clearly indicated that mandimycin caused a rapid efflux of potassium ions in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2b). Further electron microscopy analysis revealed that, in the presence of mandimycin, the cell membrane of C. albicans exhibited cleavage after 2 h and collapsed completely after 8 h of treatment, suggesting that mandimycin disrupts the integrity of fungal cell membranes (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 13).

a, Time-dependent killing curve of mandimycin against C. albicans BNCC 186382, with CFU counts measured from 0 to 48 h after exposure to mandimycin at concentrations ranging from 2× to 32× MIC. b, Quantification of potassium ions released from C. albicans BNCC 186382 after treatment with varying concentrations of mandimycin. c, A scanning electron microscopy image of C. albicans BNCC 186382 after treatment with 32× MIC of mandimycin under the same conditions as the time-dependent killing curves. Scale bars, 10 μm (left) and 5 μm (right). d, Measurement of mutation frequency in different Candida strains in the presence of polyene macrolide antibiotics. Resistant mutations were induced using 8× MIC of mandimycin, amphotericin B, natamycin and nystatin with 109 fungal cells. All experiments were performed in three biological replicates (data are mean ± s.d., one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)). e,f, ITC plots of mandimycin and amphotericin B titrated with ergosterol (e) or cholesterol (f). The experiment was repeated three times independently with consistent results. g, UV–vis spectra of mandimycin and amphotericin B co-incubated with different ratios of ergosterol. AmpB, amphotericin B; Chol, cholesterol; Erg, ergosterol; H, enthalphy; Mand, mandimycin; Nata, natamycin; Nys, nystatin; ND, not detected; NS, no significant difference.

Source Data

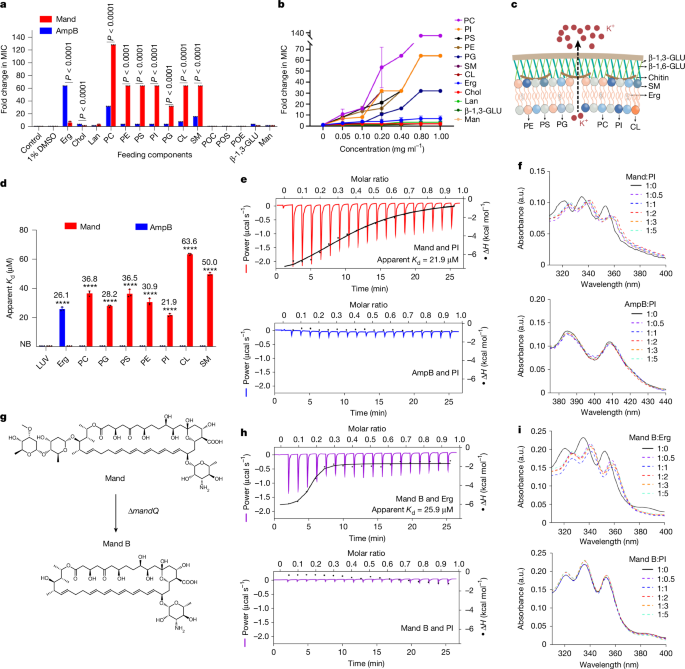

In an attempt to explore the biological target of mandimycin, we sought to isolate resistant mutants by plating a high number of fungal cells (that is, 109 cells) on agar plates containing low concentrations of antibiotics. Although polyene macrolide antibiotics seldom generate resistance after many years of clinical use as they target the small molecule ergosterol rather than proteins, we successfully obtained mutants of six Candida species resistant to natamycin, nystatin and amphotericin B, with a mutation rate ranging from 2 × 10−9 to 566 × 10−9. In particular, the mutation rate can reach 566 × 10−9 for Candida tropicalis. By contrast, mandimycin did not induce any mutants under the same conditions (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 6). Furthermore, mandimycin remains active against those strains resistant to polyene antifungal drugs, suggesting that the polyene macrolide antibiotics in clinical use do not confer cross-resistance to mandimycin and the target of mandimycin may not be ergosterol (Supplementary Fig. 14). Polyene macrolide antibiotics, exemplified by amphotericin B, have been shown to extract ergosterol through a sterol sponge pathway of antifungal activity in recent studies23,24,25,26,27. To investigate whether mandimycin exerts its antifungal activity through the same mechanism, we measured the MICs of mandimycin, along with the ergosterol-binding polyene macrolide antibiotics amphotericin B and nystatin, against C. albicans in the presence of different concentrations of ergosterol. The results revealed that the antifungal efficacy of mandimycin is entirely unaffected by the presence of ergosterol, whereas the MIC values of amphotericin B against C. albicans showed a positive correlation with ergosterol in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3a,b and Extended Data Fig. 3). To further confirm the difference, we then conducted sterol extraction and synergy antifungal assays. However, treatment with mandimycin did not result in any changes in the level of ergosterol remaining in the cell membrane (Supplementary Fig. 15). Moreover, the co-addition of the ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitor fluconazole did not exhibit any synergistic effects with mandimycin (Supplementary Fig. 16). Furthermore, both isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and UV–visible (UV–vis) binding assays did not detect any binding signals between mandimycin and sterols (that is, ergosterol and cholesterol) (Fig. 2e–g and Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5). Therefore, our study confirmed that mandimycin has a distinct antifungal mode of action, different from polyene macrolide antibiotics that target ergosterol.

a,b, MIC-fold changes in mandimycin and amphotericin B against C. albicans BNCC 186382 in the presence of a fixed concentration (1 mg ml−1) and varying concentrations (0.05–1 mg ml−1) of fungal cell membrane components. The assay was performed three times independently (n = 3, two-way ANOVA). c, Schematic illustrating the proposed mode of action of mandimycin on fungal cell membranes. d, ITC assay measuring the binding affinity of mandimycin and amphotericin B to phospholipids and ergosterol. Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs, 0.1 µm) made by 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) were used as the negative control (n = 3, two-way ANOVA, ****P < 0.0001). e,f, Representative ITC plots (e) and UV–vis spectra (f) of mandimycin and amphotericin B titrated with phosphatidylinositol (PI). The experiments were repeated three times independently, yielding consistent results. g, Knockout of the glycosyltransferase gene mandQ led to the production of the bis-deglycosylated analogue mandimycin B. h,i, Representative ITC plots (h) and UV–vis spectra (i) of mandimycin B titrated with ergosterol and PI. Data are mean ± s.d. in a, b and d. CL, cardiolipin; β-1,3-GLU, β-1,3-glucan; β-1,6-GLU, β-1,6-glucan; Lan, lanosterol; Man, mannose; Mand B, mandimycin B; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PS, phosphatidylserine; POC, phosphorylcholine; POE, phosphorylethanolamine; POS, phosphoserine; SM, sphingomyelin. NB, no binding.

Source Data

Pathogens tend to develop antibiotic resistance through targeted mutations when the biological target of an antibiotic is a protein (for example, lanosterol 14-α-demethylase for fluconazole and FKS1 for caspofungin). Antibiotics with targets exhibiting low susceptibility to resistance mutations are more likely to involve small molecules or non-protein macromolecules rather than proteins. This phenomenon has been often observed in various antibiotics, including teixobactin28, cilagicin9 and clovibactin29. Considering the ability of mandimycin to collapse cell membranes without inducing resistance, we hypothesize that its target is probably non-protein molecules present in the fungal cell membrane. To identify potential non-protein targets that mandimycin interacts with, we conducted an extensive screening of chemical components in the fungal cell membrane. We determined the MICs of mandimycin against C. albicans in the presence of fixed (1 mg ml−1) and increasing concentrations (0.05–1 mg ml−1) of fungal cell membrane components, including various phospholipids and sterols. The results showed that mandimycin does not interact with the common non-protein targets such as sterols and β-1,3-glucan. However, dose-dependent inhibition was observed with phospholipids, including phosphatidylcholine, cardiolipin, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine, sphingomyelin and phosphatidylglycerol (Fig. 3a–c and Extended Data Fig. 3). Phospholipids, the essential lipids found in fungal cell membranes, have a crucial role in maintaining membrane integrity and intracellular homeostasis30. They consist of glycerol-3-phosphate with two hydrophobic fatty acyl chains, accompanied by various substituents such as choline, serine and ethanolamine. To determine the interaction between mandimycin and phospholipids, a UV–vis binding experiment was conducted. We observed a notable red shift in the UV–vis spectrum of mandimycin after the addition of phospholipids (that is, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylserine or phosphatidylcholine) (Fig. 3f and Extended Data Fig. 5), suggesting that mandimycin forms complexes with these phospholipids. These findings suggest that mandimycin may bind to essential phospholipids, potentially inducing membrane collapse. To further determine the binding affinity between mandimycin and phospholipids, ITC experiments were performed (Extended Data Fig. 4). We observed direct and specific interactions between mandimycin and various phospholipids, as indicated by a measured dissociation constant (apparent Kd) of 21.9–63.6 μM (Fig. 3d,e and Extended Data Fig. 4). The stoichiometry of binding between mandimycin and each phospholipid is approximately 1:2 with N values ranging from 0.4 to 0.6 (Supplementary Table 7). Among the assayed phospholipids, phosphatidylinositol showed the highest binding affinity to mandimycin with an apparent Kd value of 21.9 μM, followed by phosphatidylglycerol and phosphatidylethanolamine. This surpasses the binding affinity observed between amphotericin B and ergosterol (apparent Kd of 26.1 μM) and between nystatin and ergosterol (apparent Kd of 24.9 μM) (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 4). These findings collectively confirmed that mandimycin exerts its fungicidal activity by specific binding to various phospholipids, particularly phosphatidylinositol, leading to dose-dependent ion leakage and subsequent cell collapse. However, owing to the lack of a well-established labelling method for phospholipids, it remains uncertain whether mandimycin causes ion leakage and cell collapse through a modified sponge mechanism that extracts phospholipids from lipid bilayers or through an ion channel mechanism that causes ion leakage. We then proceeded to investigate the key structural motif contributing to the distinctive mechanism of mandimycin. To achieve this, a mutant strain of S. netropsis was constructed by deleting the mandQ gene (Extended Data Fig. 6). This gene encodes the glycosyltransferase responsible for transferring the unique dideoxysaccharide atratcynose A to the polyene macrolide scaffold of mandimycin. As expected, fermentation of the ∆mandQ mutant strain resulted in the production of mandimycin B, which lacks the atratcynose A moiety (Fig. 3g, Extended Data Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 8 and Supplementary Figs. 17–23). Mandimycin B exhibited a weaker antifungal activity, approximately two to four times lower than mandimycin, and lost its ability to bind to phospholipids (Fig. 3h,i, Extended Data Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 9). However, mandimycin B exhibited a mode of action similar to that of known polyene macrolide antibiotics that involves binding to sterols (that is, ergosterol and cholesterol) (Fig. 3h,i and Supplementary Fig. 24). This phenomenon suggests that the unique dideoxysaccharide moiety found in mandimycin has a crucial role in its ability to bind to phospholipids. Miltefosine, an alkyl phosphocholine drug approved for the treatment of leishmaniasis, exerts its antiparasitic and antifungal effects by disrupting cell membranes31, probably through interactions with sterols or phospholipids; however, the detailed mechanism remains unclear32,33,34. Mandimycin is an antifungal molecule that acts by specifically targeting phospholipids.

Toxicity and animal efficacy

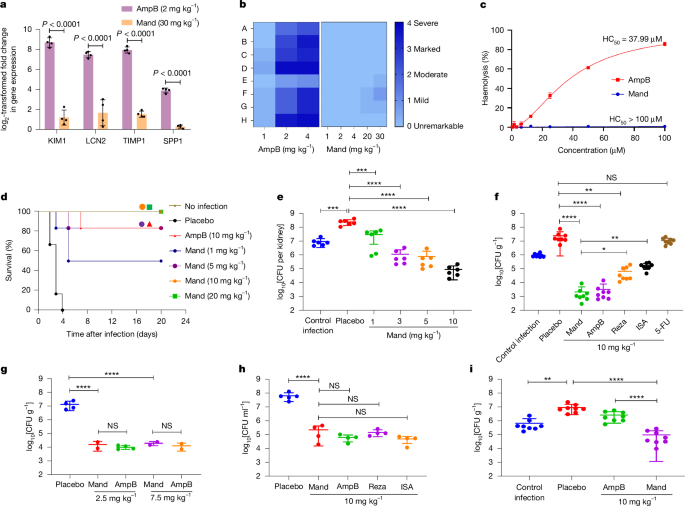

Kidney injury and haemolysis are common and severe side effects associated with the use of polyene antifungals35. Owing to its compelling biological activity and previously undescribed mode of action, we further explored the toxicity and in vivo efficacy of mandimycin. In the in vitro cytotoxicity assay, mandimycin displayed low toxicity against human renal proximal tubular epithelial (HK-2) cells and human primary renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTEC), as well as other human cell lines (that is, HepG2, PANC-1 and SK-Hep1), with half-maximal inhibitory concentrations ranging from 48.28 to 88.67 µM, which is 7–22 times weaker than that of amphotericin B (Supplementary Fig. 25a). Next, we assessed the in vivo nephrotoxicity of mandimycin in mice using both intravenous and subcutaneous injections. The maximum doses chosen were 30 mg kg−1 for mandimycin and 4 mg kg−1 for amphotericin B, as higher concentrations resulted in acute toxicity. The results revealed that kidney injury biomarkers (that is, KIM-1, LCN-2, TIMP-1 and SPP-1) remained largely unchanged at both transcription and protein levels, even at the maximum dosage. By contrast, we observed a notable increase in kidney injury biomarkers at doses of 1–2 mg kg−1 of amphotericin B (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 8). Histopathological evaluation of kidney sections revealed that mandimycin induced mild renal changes, characterized mainly by the presence of tubular protein casts in the cortex, after a single intravenous dose of 30 mg kg−1 in healthy mice. In contrast to mandimycin, moderate to severe kidney damage was observed across all histopathological scores for amphotericin B at an intravenous dose of 2 mg kg−1 (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 8). These findings clearly indicate that mandimycin has significantly lower nephrotoxicity than amphotericin B. Furthermore, mandimycin did not display any haemolytic effects even at concentrations as high as 100 µM (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 25b). Moreover, mandimycin exhibited favourable pharmacokinetic parameters, with a half-life of 3.84 h, a maximum concentration (Cmax) of 55,168.20 ng ml−1 and an area under the curve (AUC0–∞) of 541,692.11 h ng−1 ml−1 (Extended Data Fig. 9).

a, Transcription analysis of changes in kidney injury biomarkers in female mice measured 24 h after a single intravenous dose (n = 4 mice per group, two-way ANOVA). Data are mean ± s.d. b, A heat map of kidney histopathological scores (A, tubular cellular casts, cortex; B, tubular cellular casts, medulla; C, tubular degeneration and necrosis, cortex; D, tubular degeneration and necrosis, medulla; E, tubular dilatation, cortex; F, tubular protein casts, cortex; G, tubular protein casts, medulla; H, vascular congestion, bleeding, medulla). c, Haemolysis assay of mandimycin and amphotericin B using defibrated sheep blood. Mandimycin exhibited no obvious haemolysis. d,e, Survival curves (d) and kidney fungal burden (e) after different doses of mandimycin in the neutropenic disseminated candidiasis model of mice infected with MDR C. albicans BNCC 16382 (n = 6 per group for survival curves, n = 3 per group for kidney fungal burden, one-way ANOVA, ***P = 0.0006, ****P < 0.0001). f–h, In vivo antifungal efficacy of mandimycin in the neutropenic thigh-infection mouse model for C. neoformans BNCC 225501 (f) (n = 4 per group, one-way ANOVA, *P = 0.035, **P < 0.0016, ****P < 0.0001) and the skin-infection mouse model (g) and the vaginitis mouse model (h) for C. albicans BNCC 16382 (n = 4 per group, one-way ANOVA, ****P < 0.0001). i, In vivo antifungal efficacy of mandimycin in the neutropenic thigh-infection model of mice infected with amphotericin-B-resistant MDR C. auris AM05 (n = 4 mice per group, one-way ANOVA, **P = 0.0019, ***P = 0.0008, ****P < 0.0001). In all mouse models, the therapeutic compounds and vehicles were administered by subcutaneous injection, and the fungal burden was determined after drug treatment. ISA, isavuconazole; Reza, rezafungin. HC50, concentration needed to cause haemolysis of 50% of the red blood cells.

Source Data

To investigate the in vivo therapeutic efficacy of mandimyicn, we established mouse infection models to simulate various fungal infections, including systemic, soft-tissue and cutaneous-related infections. Invasive candidiasis causes considerable morbidity and mortality each year, with many cases caused by MDR fungal pathogens. Thus, we initially used the invasive candidiasis model to evaluate the effectiveness of mandimycin in treating systemic infection caused by MDR C. albicans BNCC 186382 (which is resistant to fluconazole, 5-fluorocytosine and terbinafine). After administration of 1, 5, 10 and, 20 mg kg−1 of mandimycin (subcutaneous, once a day) for four consecutive days, a dose-dependent increase in survival rate was observed. Notably, at a dose of 10 mg kg−1, the survival rate of mice reached 100%. By contrast, the survival rate in the amphotericin B group reached only 80% (Fig. 4d), indicating the superior efficacy of mandimycin in improving survival. To assess the efficacy of mandimycin in systemic infection, we quantified the fungal burden in major organs using a disseminated candidiasis model. Mandimycin demonstrated a dose-dependent reduction in fungal burden in the major organs. Specifically, when mandimycin was administered by subcutaneous injection once daily at doses of 1, 3, 5 and 10 mg kg−1, the cell counts of MDR C. albicans decreased by 0.93, 2.34, 2.52 and 3.43 log10-transformed CFU per kidney as seen in kidney sections over a 24-h period (Fig. 4e). A similar trend was also observed in the lung sections (Extended Data Fig. 10a). Notably, mandimycin displayed similarly potent efficacies through oral administration and intravenous injection. The fungal burden decreased by more than 2.5 log10-transformed CFU per gram of lung after oral administration of 5 mg kg−1 of mandimycin (once daily) (Extended Data Fig. 10b,c). The reduction level correlated directly with the dose of mandimycin. Furthermore, in mice with systemic MDR fungal infections, 1 mg kg−1 of mandimycin (intravenous injection) showed potent dose-dependent antifungal efficacy, reducing fungal burdens in the kidney and lung by more than 3 log10-transformed CFU per gram of organ. At 20 mg kg−1, mandimycin further reduced the fungal burden by more than 5 log10-transformed CFU per gram of organ without observable side effects (Extended Data Fig. 11), whereas the fungal burden of mice treated with 5 mg kg−1 amphotericin B was lethal, killing all mice within 1 day. Given that a 10-fold decrease (1 log10) in CFU is considered indicative of efficacy in humans36, the findings suggest that mandimycin has excellent in vivo efficacy against MDR fungal pathogens for the treatment of systemic infections. Next, we investigated the efficacy of mandimycin in treating soft-tissue infections caused by three MDR fungal pathogens (that is, MDR C. albicans BNCC 186382, MDR C. auris BNCC 357785 and MDR C. neoformans BNCC 225501) using a neutropenic thigh-infection model. Mandimycin exhibited potent and dose-dependent effects against Candida infections, resulting in a 30-fold decrease (3 log10) in fungal burden after subcutaneous injection of 10 mg kg−1 (Extended Data Fig. 10d,e). Furthermore, mandimycin exhibited even higher efficacy against MDR C. neoformans, achieving a more than 40-fold decrease (4 log10) after a dose of 10 mg kg−1 administered once daily over 24 h (Fig. 4f). Notably, the efficacy surpassed that of three other types of antifungal drugs (rezafungin, isavuconzole and 5-fluorocytosine).

Finally, we investigated the efficacy of mandimcyin in treating cutaneous-related infection. Mandimycin displayed potent activity in skin-infection models, with a fungal burden decrease of more than 2 log10-transformed CFU g−1 after a dose of 2.5 mg kg−1 and a substantial reduction in wound size and inflammation. (Fig. 4g, Extended Data Fig. 10f and Supplementary Fig. 26). In the treatment of vaginal candidiasis, a prevalent fungal infection affecting approximately 75% of women at least once in their lifetime, mandimycin also revealed potent efficacy, resulting in a notable reduction in vaginal fungal burden by 2.51 log10-transformed CFU ml−1 after a 5-day treatment (10 mg kg−1, subcutaneous, once a day). This efficacy is comparable to other well-known antifungal antibiotics, including amphotericin B, rezafungin and isavuconazole (Fig. 4h). Furthermore, mice treated with mandimycin exhibited obvious alleviation of inflammation and almost complete restoration of the vaginal mucosa (Supplementary Fig. 27).

Clinically, owing to its low frequency of resistance and broad-spectrum activity, the polyene macrolide antibiotic amphotericin B has been used as a crucial antifungal for treating life-threatening MDR fungal infections, including those that have become resistant to other antifungal agents37. However, the emergence of pandrug-resistant C. auris, capable of resistance to all four classes of antifungal drug, has eliminated viable treatment options, triggering a global concern38,39,40,41. To assess the efficacy of mandimycin as a last-line antibiotic against pandrug-resistant pathogens, we established an in vivo infection mouse model using amphotericin-B-resistant MDR C. auris AMR05 (Table 1 and Fig. 4i). Remarkably, amphotericin B showed ineffectiveness in reducing the burden (0.4 log10) of MDR C. auris even at a subcutaneous dose of 10 mg kg−1. By contrast, mandimycin demonstrated substantial efficacy at the same dose, resulting in a fungal reduction of more than 2.3 log10-transformed CFU g−1 (Fig. 4i). Taken together, mandimycin demonstrated potent in vivo activity against various MDR fungal pathogens, while also exhibiting low nephrotoxicity and no haemolytic effect at doses effective at eliminating fungal infections.

Conclusion

Fungal infections caused by MDR pathogens pose a serious threat to human health, necessitating the development of treatments to address them. The challenge of identifying viable fungal targets and the reduced effectiveness of the traditional activity-based natural-product drug discovery approach have resulted in the currently limited number of clinical antifungal drugs1. With the advancement of sequencing technology, we have come to realize that nearly all clinical resistance mechanisms can be tracked back to microorganisms that possess intrinsic or acquired resistance in nature42. Over billions of years of evolution, BGCs in antibiotic-producing microorganisms might have evolved to produce more effective antibiotics with distinctive modes of action to combat resistant bacteria5. Leveraging the power of evolution can guide us in the discovery of structurally distinct antibiotics with previously unknown modes of action, such as macolacin8, corbomycin10 and malacidin15.

In this study, we focused on the conserved mycosamine motif, a feature common to known polyene macrolide antifungals, for the phylogeny-guided discovery of antifungal antibiotics. Through mining of glycosyltransferases involved in mycosamine transfer onto the macrolide skeleton in the BGCs of polyene macrolide antibiotics, we identified mandimycin, a previously undescribed polyene macrolide antibiotic exhibiting potent broad-spectrum antifungal activity and a distinctive mode of action. Unlike polyene macrolide antibiotics reported so far, mandimycin possesses a mycosamine and a rare dideoxy sugar motif, resulting in markedly enhanced aqueous solubility more than 9,700 times higher than that of the widely used antifungal polyene drug amphotericin B.

Mandimycin exhibited its fungicidal activity through a unique mechanism. In contrast to the majority of known polyene macrolide antibiotics that target ergosterol, mandimycin exerts its fungicidal effect by specifically binding to various types of phospholipid present in fungal cell membranes, with a particular affinity for phosphatidylinositol. This multiple binding ability not only imparts robust fungicidal properties but also poses a formidable challenge for the development of resistant mutants owing to the improbability of concurrent mutations in all seven phospholipid-related pathways. The differential activity observed against bacterial, fungal and mammalian cells suggested that mandimycin has selectivity towards phospholipids present on the fungal cell envelope. In our in vivo assay, mandimycin exhibited a favourable pharmacokinetic profile and lower nephrotoxicity compared with amphotericin B, while showing potent fungicidal effects against various MDR fungal pathogens in different models of infections in mice. The discovery of mandimycin using the phylogeny-guided natural-product discovery strategy represents an important step forward in the search for antifungal agents with distinct modes of action and low toxicity. Its unique structure and mechanism offer a promising avenue for the development of antifungal therapies. Further studies are needed to assess the potential efficacy and toxicity of mandimycin in clinical settings as well as the feasibility of phospholipids as potential antifungal targets in drug development.

Methods

Identification and bioinformatic analysis of mandimycin BGC

To identify potential BGCs encoding previously unknown mycosamine-containing polyene macrolide antibiotics, a localized MiSM database was constructed using microbial genome sequencing data, including ‘complete’, ‘chromosome’, ‘scaffold’ and ‘contig’ assemble levels, from The National Center for Biotechnology Information. Moreover, 150 isolated Streptomyces genomes sequenced in our laboratory were incorporated into the MiSM database. Next, putative BGCs in these genomes were predicted and annotated using antiSMASH v.7.0 with four extra features (that is, known cluster blast, subcluster blast, MiBiG cluster comparison and active site finder)11. The identified BGCs were organized in a local server using the MySQL model under the DB-API database frame. A customized profile Hidden Markov Model (pHMMer)43 was built using 11 known glycosyltransferase sequences detailed in Supplementary Table 1 and used to scan against the localized MiSM database. A cut-off e-value of 5e−181 was used to identify sequences encoding glycosyltransferases responsible for transferring the mycosamine motif onto the polyene macrolide ring of potential polyene macrolide antibiotics. Candidate sequences were subsequently trimmed and aligned using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis v.11 (MEGA11) software with the Muscle algorithm44. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbour-joining method and visualized on the interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) website45.

Knockout of mandL and mandQ in S. netropsis

To validate the mand BGC and obtain the bis-deglycosylated counterpart, we constructed targeted deletion mutants of the polyketide synthase gene (ΔmandL) and the di-digitoxose glycosyltransferase gene (ΔmandQ). In brief, two fragments, one upstream and one downstream of the targeted gene, were PCR-amplified from the genomic DNA of S. netropsis DSM 40259 using primer pairs MandL_KOUF/MandL_KOUR and MandL_KODF/MandL_KODR for mandL and MandQ_KOUF/MandQ_KOUR and MandQ_KODF/MandQ_KODR for mandQ, respectively. These amplicons were then cloned into the vector pKC1139 digested with BamHI for mandL or XbaI for mandQ, yielding the plasmids pKC1139-MandL_KO and pKC1139-MandQ_KO. These constructs were subsequently introduced into S. netropsis DSM 40259 through Escherichia coli–Streptomyces conjugation, and apramycin-resistant exconjugants were selected and incubated in mannitol soya flour (MS) medium at 30 °C to generate double-crossover mutants. Deletion of mandL and mandQ was verified by PCR analysis using the primer pairs MandL_KOUF/MandL_KODR and MandQ_KOTF/MandQ_KOTR, respectively. The resulting PCR products were further confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Fermentation of S. netropsis and purification of mandimycin

Spores of S. netropsis DSM 40259 were generated by culturing on ISP4 agar plates at 30 °C for 7 days. Spores were aseptically inoculated into a 50 ml starting culture of tryptic soy broth in 250-ml baffled Erlenmeyer flasks using sterile inoculum sticks. The flasks were incubated with agitation at 30 °C for 2 days. Next, 0.5 ml of the tryptic soy broth seed culture was used to inoculate 50 ml of F2 medium (glucose 69 g l−1, beef extract 25 g l−1, CaCO3 9 g l−1 and KH2PO4 0.1 g l−1) in 250 ml baffled Erlenmeyer flasks. Mandimycin B was fermented in FS/9 medium (soybean meal 30 g l−1, glucose 40 g l−1 and CaCO3 10 g l−1). The flasks were then agitated at 30 °C, 200 rpm for 10 days. The cultures, including the mycelia, were extracted overnight using n-butanol at a 1:1 ratio. The resulting organic extract was separated and concentrated using a rotary evaporator. The concentrated extracts were then fractionated on a YMC-GEL C18 column using a stepwise gradient elution of methanol/water (10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 90% and 100% methanol). The fractions containing mandimycin were identified using ultraperformance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (Waters), and the pure form of mandimycin was further purified through reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Shimadzu, ShimNet HE C18-AQ, 5 μm optimal bed density (OBD), 19 × 250 mm, 3 ml min−1 from 30% to 90% acetonitrile in water over 60 min). The purity and identity of mandimycin were confirmed by ultraperformance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. The target HPLC fractions were combined and lyophilized, yielding a pure powder for subsequent biological assays.

Structure elucidation of mandimycin and mandimycin B

To elucidate the structures of mandimycin and mandimycin B, the purified compounds were analysed by NMR spectroscopy (Bruker AVANCE NEO 600 MHz and Bruker AVANCE III HD 700 MHz) and HR-ESI–MS (Waters-Gs-XS-QTOF and Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Orbitrap). Mandimycin or mandimycin B (around 20 mg for each) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-d6 for one-dimensional (1H and 13C) and two-dimensional (HSQC, HMBC, 1H-1H COSY, TOCSY, NOESY) NMR analysis. (HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum coherence; HMBC, heteronuclear multiple bond correlation; COSY, correlation spectroscopy; TOCSY, total correlation spectroscopy; NOESY, nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy). NMR data were acquired on either a Bruker AVIII 600 MHz instrument equipped with a cryoprobe or a Bruker AVIII 700 MHz instrument. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethyl silane using the residual solvent signals at 2.50 ppm in 1H NMR and 39.5 ppm in 13C NMR as internal signals. HR-ESI-MS data were acquired on an Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer under both positive and negative ionization modes by direct infusion. The acquired data were further processed using Xcalibur software. A detailed interpretation of NMR and HR-ESI–MS data for the structure elucidation of mandimycin and mandimycin B is provided in the Supplementary Information.

MIC assay

The in vitro antimicrobial potency of mandimycin and mandimycin B was assessed by determining their MIC values following the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute19. Mandimycin was tested against a panel of fungal pathogens as well as Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens, as detailed in Supplementary Table 4. The assays were performed in 96-well microlitre plates, with amphotericin B, vancomycin and ciprofloxacin serving as positive controls for fungal, Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, respectively. All test compounds were dissolved in sterile DMSO (SCR, CN) to achieve a concentration of 12.8 mg ml−1. Assay strains were cultured from a single colony overnight and subsequently diluted 5,000-fold in fresh Luria Bertani (LB) (bacteria) or yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) (fungi) medium. The microbial suspension was subsequently distributed into the first row (100 µl per well) and the rest of the rows (50 µl per well). The test compounds were serially diluted across 96-well plates using a twofold serial dilution in a volume of 50 µl to give a range of final concentrations of each compound between 64 and 0.125 μg ml−1. To avoid edge effects, the top and bottom rows of each plate were filled with 100 µl of medium. Plates were incubated at 37 °C (bacteria) or 30 °C (fungi) for 16 h. The lowest concentration at which there was no visible growth of bacteria or fungi was recorded as the MIC. All assays were performed in duplicate and repeated three independent times.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of mandimycin and mandimycin B was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay46. HepG2 (human hepatoblastoma cell line), HK-2 (human renal proximal tubule epithelial cell line), SK-Hep-1 (human hepatic adenocarcinoma cell line) and PANC-1 (human pancreatic cancer cell line) cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum until the exponential phase was reached. RPTEC cells were cultured in renal epithelial cell basal medium supplemented with a renal epithelial cell growth kit until the exponential phase was reached. Subsequently, cells were seeded into a 96-well, flat-bottom microlitre plate at a density of 2,500 cells per well. After 24-h incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2, the medium was aspirated and replaced with 100 μl of fresh medium containing mandimycin or mandimycin B at concentrations ranging from 128 μg ml−1 to 0.25 μg ml−1. After an additional 48-h incubation, the culture medium was removed, and 110 μl of MTT solution (10 μl of 5 mg ml−1 MTT in PBS premixed with 100 μl of DMEM) was added into each well. The mixture was incubated for an additional 3 h at 37 °C to enable formazan crystal formation, followed by solubilization with 100 μl of solubilization solution (40% dimethylformamide, 16% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 2% acetic acid in H2O). The absorbance of each well was measured at an optical density at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer, BioTek). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration values of mandimycin and mandimycin B were calculated (GraphPad Prism 9) as the concentration of compound required to inhibit 50% of cell growth, relative to control wells without any compound. All experiments were performed in three biological replicates.

Feeding assay

The impact of fungal cell membrane components on the antifungal activity of mandimycin was evaluated using C. albicans BNCC 186382. Membrane components including ergosterol, cholesterol, lanosterol, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylglycerol, cardiolipin, sphingomyelin, phosphorylcholine, phosphoserine, phosphorylethanolamine, β-1,3-glucan, β-1,6-glucan and mannose were prepared in 10% sterile DMSO. Each solution (10 μl) was added to individual wells of 96-well microtitre plates, resulting in final concentrations of these cell membrane components of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8 and 1.0 mg ml−1. The MIC value of each treatment against C. albicans was recorded using the same method described for the MIC assay. The experiment was conducted in three biological replicates.

ITC assay

The binding of mandimycin to phospholipids (phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, cardiolipin, sphingomyelin and phosphatidylglycerol) and sterols (ergosterol and cholesterol) was measured using ITC. LUVs with a size of 0.1 μm were prepared by mixing DOPC (Avanti Polar Lipids) and 5% of each phospholipid or sterol in chloroform (1:1). The resulting lipid suspension was evaporated to dryness in vacuo to yield a lipid film, followed by rehydration using 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl). Subsequently, the hydrated sample was extruded ten times through a 0.1-μm filter membrane using an Avanti Mini Extruder. ITC experiments were performed on a PEAQ-ITC instrument at 25 °C using a solution of 1 mM of mandimycin, mandimycin B or amphotericin B along with 600 µM DOPC LUVs. The titration process involved an initial injection of 0.23 μl, followed by 18 injections of 2 μl at 80-s intervals, with continuous stirring at 500 rpm. Data were analysed using PEAQ-ITC software, and the thermodynamic parameters (enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS) and the equilibrium binding constant (apparent Kd)) were calculated using a one-binding-site model.

UV–vis spectroscopy for sterol and phospholipid binding

To investigate the potential formation of complexes between mandimycin and mandimycin B with sterols or phospholipids, the UV–vis binding assay was carried out following established protocols27. A stock solution (100 mM) of each phospholipid (that is, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, cardiolipin and sphingomyelin) and sterol (that is, ergosterol and cholesterol) was prepared in chloroform and subsequently diluted to a final concentration of 1 mM using DMSO. Mandimycin or mandimycin B was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a stock solution of 10 mM, which was further diluted to a working concentration of 1 mM using DMSO. Amphotericin B and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Complexes were prepared by mixing the stock solutions in various ratios to achieve a final volume of 1 ml. The mixture was then incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The UV–vis absorbance spectra ranging from 310 to 400 nm were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Multiskan SkyHigh instrument and plotted using Origin 2021 (v.9.8).

Isolating resistant mutants

Single colonies of various pathogenic fungal species (C. auris BNCC 357785, C. albicans BNCC 186382, C. neoformans BNCC 225501, C. glabrata BNCC 337348 and C. tropicalis BNCC 340288) were cultured overnight in 5 ml YPD broth at 30 °C with continuous shaking at 200 rpm. The overnight culture was diluted to a concentration of 109 cells per 100 µl using fresh YPD medium and plated onto an YPD agar plate containing 8× MIC of tested compounds (that is, mandimycin, amphotericin B, nystatin and natamycin). Plates were statically incubated at 30 °C for 2 days, and resistant colonies were observed and recorded. MIC values of selected resistant mutants were determined using the same method as described for the MIC assay.

In vivo nephrotoxicity assay

Specific-pathogen-free female Insitute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice, aged 6 weeks and weighing 23–27 g, were used in this study (Hangzhou Medical College, China). The mice were randomly housed in individual cages and divided into 12 groups with 4 mice per group. Mice were acclimatized for 3 days before the experiments. Amphotericin B or a solvent without any antibiotics was used as the positive control and placebo, respectively. Compounds were formulated in a solution containing 10% DMSO and 10% Tween 80. Subsequently, each group of mice received daily subcutaneous or intravenous injection of various concentrations of the tested compounds or a placebo. The protein concentrations of toxicity-related biomarkers, including KIM-1, TIMP-1, LCN-2 and SPP-1, were measured using commercial kits (Cloud-Clone), following the protocols provided. Gene expression levels of Kim1, Timp1, Lcn2 and Spp1 were assessed using reverse-transcription PCR with specific primer sets (Kim1F/R, Lcn2F/R, Timp1F/R and Spp1F/R), with Gadph as a control. The quantifications were performed using Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3. Finally, all animals were euthanized, and the kidney tissues were collected, fixed, dissected and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Pathological changes in tubular degeneration, necrosis, cellular casts, dilation, congestion and protein casts were evaluated and scored in a double-blinded fashion by a clinical pathologist. All animal study procedures were approved by Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (approval numbers 2024-02-007 and 2024-09-130).

Neutropenic mouse thigh-infection model

Specific-pathogen-free female ICR mice, aged 6 weeks and weighing 23–27 g, were used in the current study (Hangzhou Medical College, China). The mice were randomly housed in individual cages and acclimatized for 3 days before the experiments. Neutropenia was induced on day 1 and day 4 through intraperitoneal injection of 150 mg kg−1 and 100 mg kg−1 of cyclophosphamide, respectively. A singe colony of C. albicans BNCC 186382, C. albicans BNCC 357785, Cryptococcus neoformans BNCC 225501 or amphotericin-B-resistant C. auris AMR005 was inoculated into 5 ml YPD liquid medium and shaken overnight at 30 °C, 220 rpm. The overnight fungal culture was washed three times with 0.9% sterile saline solution and then diluted to a final concentration of 2 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) per ml. The diluted fungal suspension (50 µl) was administered by intramuscular injection into both thighs, which provides an inoculum of approximately 1.0 × 106 CFU in each thigh. For the thigh-infection model with the Cryptococcus strain, mice were treated with mandimycin (formulated in 10% DMSO + 10% Tween 80) at a dose of 10 mg kg−1, once daily, 6 h after infection. Amphotericin B, rezafungin, isavuconzole and 5-fluorocytosine were used as controls. For the thigh-infection model with the Candida strain, mice were treated with mandimycin (formulated in 10% DMSO + 10% Tween 80) at doses of 20 mg kg−1, 10 mg kg−1 and 5 mg kg−1 or with the vehicle (10% DMSO + 10% Tween 80) at 2, 10 and 18 h after infection. The mice were euthanized, and their thigh muscles were aseptically removed, weighted, homogenized and enumerated for fungal burden by CFU counts after plating on YPD agar and incubated at 30 °C. All graphical data are presented as individual data points per group and were statistically analysed using GraphPad Prism 9. All animal study procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (approval numbers 2023-08-018, 2023-09-036 and 2023-09-033).

Neutropenic mouse model for disseminated candidiasis

Specific-pathogen-free female ICR mice, aged 6 weeks and weighing 23–27 g, were used for the current study (Hangzhou Medical College, China). The mice were randomly housed in individual cages with four mice per cage and acclimatized for 3 days before the experiments. A singe colony of C. albicans BNCC 186382 was inoculated into 5 ml of YPD liquid medium and shaken overnight at 30 °C, 220 rpm. The overnight fungal culture was washed three times with 0.9% sterile saline solution and then diluted to a final concentration of 2 × 107 CFU ml−1. Subsequently, 50 µl of the diluted fungal suspension was administered by subcutaneous injection into the tail vein, resulting in an inoculum of approximately 1 × 107 CFU in the bloodstream. Six hours after infection, mice were treated with a single dose of 1 mg kg−1, 3 mg kg−1, 5 mg kg−1 or 10 mg kg−1 of mandimycin (formulated in 10% DMSO and 10% Tween 80) through subcutaneous injection. For the oral administration group, mice were orally administered a dose of 10 mg kg−1 of mandimycin formulated in a solution containing 5% DMSO and 10% Tween 80. Twenty-four hours after infection, mice were euthanized, and their kidney and lung tissues were aseptically removed, weighted, homogenized and subjected to fungal burden enumeration by CFU counts after plating on YPD agar and incubated at 30 °C. All graphical data are presented as individual data points per group and were statistically analysed using GraphPad Prism 9. All animal study procedures were approved by Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (approval numbers 2024-04-009 and 2024-03-019).

Neutropenic mouse model for invasive candidiasis

Specific-pathogen-free female ICR mice, aged 6 weeks and weighing 23–27 g, were used for the current study (Hangzhou Medical College, China). The mice were randomly housed in individual cages with six mice per cage and acclimatized for 3 days before the experiments. To induce immunosuppression, the mice received an intraperitoneal injection of cyclophosphamide (200 mg kg−1) and subcutaneous administration of cortisone acetate (500 mg kg−1) on day −2 and day 3, respectively. To prevent cross-infections, mice were given enrofloxacin orally at a concentration of 50 μg ml−1 in drinking water from day 1 to day 3, followed by subcutaneous injections of ceftazidime (5 μg per dose) from day 0 to day 9. Invasive candidiasis was induced by intravenous injection of 1 × 106 CFU of C. albicans BNCC 186382. Treatment was started 16 h after infection, involving subcutaneous injections of ceftazidime and daily single doses of mandimycin at 1 mg kg−1, 5 mg kg−1, 10 mg kg−1 and 20 mg kg−1 as well as amphotericin B at 10 mg kg−1 for four consecutive days. The mice were monitored for a total of 20 days, and survival rates were plotted using GraphPad Prism 9. All animal study procedures were approved by Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (approval number 2024-01-014).

Neutropenic mouse skin-infection model

The mouse skin-infection mode was established to evaluate the efficacy of mandimycin in treating fungal infections on the skin47,48,49. An equal number of male and female BALB/c mice weighing 20–22 g were used for the current study (Hangzhou Medical College, China). The mice were randomly housed in individual cages with four mice per cage and acclimatized for 3 days before the experiments. Neutropenia was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg kg−1 of cyclophosphamide on the third and first days before infection. Subsequently, mice were anaesthetized with 50 mg kg−1 of pentobarbital sodium by intraperitoneal injection and underwent full-thickness skin perforation on the dorsal skin using a biopsy puncher with a diameter of 0.8 cm. A suspension of C. albicans BNCC 186382 (1 × 108 CFU ml−1, 50 μl per mouse) was inoculated into the circular wound, followed by gentle airflow until the skin appeared moist but without excess liquid. One day after infection, the wounds were topically treated with mandimycin (2.5 mg kg−1 or 7.5 mg kg−1), amphotericin B (2.5 mg kg−1 or 7.5 mg kg−1) or vehicle (PBS containing 10% DMSO and 10% Tween 80). The mice that received a wound but no fungal infection served as negative controls and were treated with vehicle only. All compounds were administered once daily for five consecutive days. The wounds were photographed and their sizes were measured on days 1, 5, 9 and 11 after infections. On day 11, fungal counts of wound specimens were recorded, and wound specimens were collected for H&E staining. All animal study procedures were approved by Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (approval number 2024-02-003).

Neutropenic mouse model for vaginal candidiasis

Female BALB/c mice, weighing 19–21 g, were acclimatized for 3 days before the experiments. The mice were randomly housed in individual cages with four mice per cage and acclimatized for 3 days before the experiments. On day 1, mice were subcutaneously injected with 10 mg kg−1 of oestradiol benzoate, once daily for five consecutive days to induce oestrus50,51. On day 6, mice were intravaginally inoculated with 50 μl of C. albicans BNCC 186382 suspension (1 × 1010 CFU ml−1) using a pipettor and were subsequently positioned upside down for 5 min after vaginal inoculation. After 3 days of consecutive infection, the mice were fed normally ad libitum food for 1 day before receiving a subcutaneous administration of mandimycin (10 mg kg−1), amphotericin B (10 mg kg−1), rezafungin (10 mg kg−1) or isavuconazole (10 mg kg−1) once daily for five consecutive days. Mice infected with C. albicans but not treated with compounds served as the control group and were administered PBS containing 10% DMSO and 10% Tween 80. On the second day after the final injection, vaginal douche was obtained by repeatedly washing the vagina with sterile PBS (20 μl) by pipetting, and the samples were plated on De Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) agar plates for counting C. albicans colonies. Finally, all animals were anaesthetized with diethyl ether and euthanized to collect the vaginal tissues, which were subsequently fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The tissues were dissected and subjected to H&E and periodic acid–Schiff staining for histological analysis. All animal study procedures were approved by Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (approval number 2024-02-003).

Single-dose pharmacokinetic study of mandimycin

Specific-pathogen-free male Sprague–Dawley rats (180–220 g, 7–8 weeks old, n = 3 per group) were used in the study. The rats were randomly housed in individual cages with three rats per cage and acclimatized for 3 days before the experiments. Rats were administered 25 mg kg−1 of mandimycin through subcutaneous injection. Blood samples (around 0.15 ml) were collected from the jugular vein catheter into tubes containing heparin sodium at 5, 10, 20 and 30 min before dosing and at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 24 h after dosing. After collection, each blood sample was placed on ice and subsequently centrifuged (8,000g, 5 min) to separate plasma. Plasma was then transferred and immediately frozen (at or below −70 °C) until analysis. Mandimycin in rat plasma was analysed using HPLC–ESI–MS/MS on an AB SCIEX Triple Quad 6500 system coupled with a HPLC system equipped with a Quaternary Solvent Manager-R solvent distribution unit and Sample Manager FTN-R auto-sampler. Diazepam was used as an internal standard. Multiple reaction monitoring with positive ion mode was used to quantify the for mass of the analytes at m/z 1,198.30 to m/z 725.20 for mandimycin and m/z 285.00 to m/z 193.00 for the internal standard. Separation of mandimycin and the internal standard was performed through HPLC (Waters ACQUITY C18 column, 1.9 μm, 100 × 2.1 mm). The isocratic mobile phase, consisting of 80% acetonitrile and 20% (v/v) 5 mM ammonium acetate, was delivered at a rate of 0.4 ml min−1 for 3 min through the mass spectrometry electrospray ionization chamber. The concentration in plasma was fitted against time using GraphPad Prism 9. The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to Cmax, apparent elimination half-life, mean residue time, area under the plasma concentration–time curve, clearance and volume of distribution values were estimated by non-compartmental analysis methods using Phoenix WinNonlin 8.3. Bioavailability was calculated by (AUCsubcutaneous/AUCintravenous) × (Doseintravenous/Dosesubcutaneous) × 100%. All animal study procedures were approved by Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (approval number 2024-02-006).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses