A portrait of the infected cell: how SARS-CoV-2 infection reshapes cellular processes and pathways

Introduction

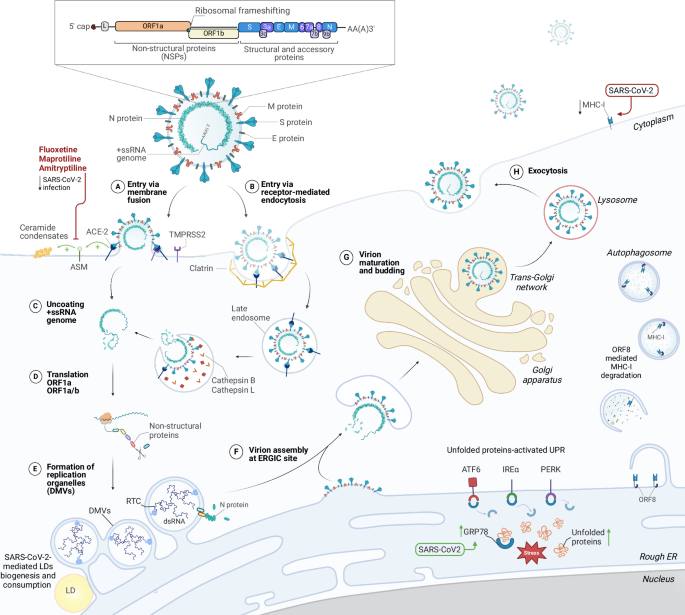

SARS-CoV-2, the aetiological agent of the fast evolving COVID-19 pandemic, belongs to the group of β-coronaviruses within the Coronaviridae family (order Nidovirales) of +ssRNA viruses1,2. After viral entry mediated by the ACE-2 receptor, SARS-CoV-2 positive-sense RNA genome is directly translated into the large ORF1a and ORF1ab polyproteins, which are then cleaved in a total of 16 non-structural proteins (NSPs). The NSPs assemble to form the replication and transcription complex (RTC), containing the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), responsible for the transcription of subgenomic and genomic viral RNA. After the interaction between the newly synthesized genomic RNA and the Nucleocapsid (N) protein, new virions assemble at the ER—Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) and are released through either the conventional secretory pathway or by exocytic lysosomes via multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (Fig. 1)3. Similarly to other +ssRNA viruses, genome replication occurs within the cytosol of the infected cells. However, the cytoplasm represents a hostile environment due to the presence of the innate immune sensors able to detect the viral RNA and the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) replication intermediate. To protect the dsRNA from the host immune sensing, +ssRNA genome replication occurs within specialised, virus-induced membrane-delimited compartments called viral replication organelles (vROs). The compartmentalisation and RNA replication step within the vROs brings several advantages: (i) the dsRNA present within the vROs interior cannot be reached by the cytosolic host immune sensors, (ii) the membrane-delimited environment allows to achieve higher local concentration of metabolites and factors required for RNA synthesis, and (iii) the separation between the replication complex from the translation and virion assembly machineries allows the spatiotemporal coordination of those different steps and prevents the three processes to interfere with each other4,5.

SARS-CoV-2 uses ACE2 and TMPRSS2 cellular receptors to enter inside the cells either by membrane fusion (A) or receptor-mediated endocytosis (B). Upon entry, the +ssRNA genome gets released from the virion and directly serves as mRNA for translation of ORF1a and ORF1ab polyproteins (C). The polyproteins are subsequently cleaved into 16 non-structural proteins which form the replication transcription complex (RTC) in the newly generated viral replication organelles in the form of double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) (D, E). After the synthesis of the sub-genomic RNAs encoding for structural proteins and accessory genes, the membrane, envelope and spike proteins traffic through the secretory compartment and accumulate at the membrane of the ER—Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC). The nucleocapsid protein (N) interacts with the newly produced viral genomes and the ribonucleocapsids are transported to the assembly sites where they interact with the structural proteins to produce novel virions on the ERGIC membranes (F). Virions undergo maturation in the Golgi apparatus and are transported from the trans-Golgi network (G) to leave the cell via the secretory pathway route or via exocytic lysosomes (H). Progression of the viral infection alters various cellular processes, such as lipid metabolism and ceramides accumulation, lipid droplets (LDs) biogenesis and consumption, autophagosomes accumulation and MHC-I expression decrease via ORF-8 mediated degradation, and ER-stress mediated UPR activation.

In the case of SARS-COV-2, vROs are composed of double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) that originate upon remodelling of the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Fig. 1). The biogenesis of the vROs and the formation of DMVs is accompanied by the general rewiring of cellular metabolic pathways as well as by structural and functional alterations of all the cellular organelles6,7.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, holistic approaches that exploited -omics techniques, such as lipidomics, interactomics and transcriptomics were used to gain insight into the full set of alterations induced during the SARS-CoV-2 infectious cycle.

In this review, we focus on three specific host pathways that are strongly impacted during SARS-CoV-2 infection, highlighting the interplay between viral and host factors in each of these processes. First, we explore the remodelling of the ER, where membranes are converted into vROs and the ER-stress response is dysregulated. Then we discuss autophagy, the only cellular process able to form physiological DMVs, a pathway exploited by many +ssRNA viruses. Finally, we investigate how lipid metabolism is rewired to feed vROs biogenesis and the lipid species implicated.

The impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on ER

ER and Golgi apparatus are the sites where three major processes of SARS-CoV-2 occur: translation, replication, and assembly. Due to the critical role of these organelles, their morphology, processes, and functions are significantly impacted during the SARS-CoV-2 replication cycle.

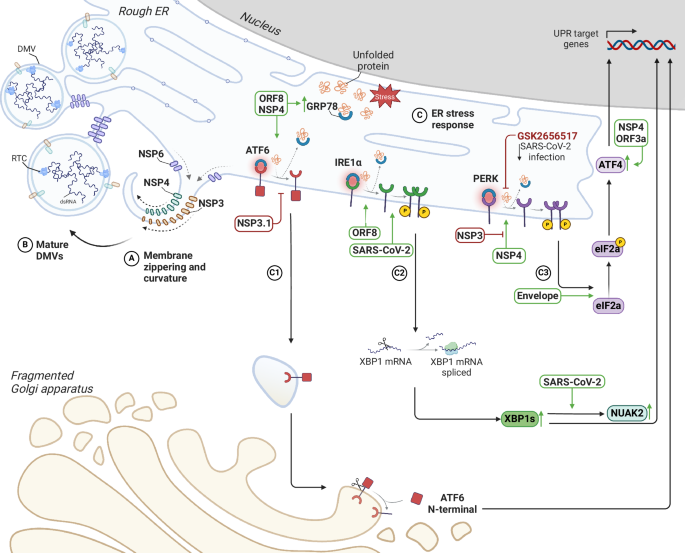

The extensive reorganisation of the ER is strongly linked to the formation of DMVs, as the ER is the main membrane supplier for DMVs biogenesis8,9. Consistent with this, confocal images of Vero E6 cells stably expressing the translocon subunit Sec61β fused to a GFP reporter reveal dense perinuclear foci of the reporter colocalising with the viral genome and the NSP3 24 h after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Moreover, super-resolution images show encapsulation of clusters of viral genomes by ER-derived ring- or sphere-like structures at early times, that grow to accommodate larger genome clusters during the infection. dsRNA and NSP12 are also found to be encapsulated by the same remodelled ER membranes suggesting that the viral genome, the dsRNA and the RdRp are all located within the same ER-derived compartment9. Those analyses corroborated previous radiolabeling electron microscopy experiments that showed accumulation of dsRNA signal in the proximity of DMVs10 and in-situ cryo-FIB-SEM experiments that demonstrated the presence of strings within the DMVs interior, whose diameter is compatible with the calculated diameter of a dsRNA molecule11. Three non-structural proteins, NSP3, NSP4, and NSP6, are critical in forming replication organelles. In particular, NSP3 and NSP4 primarily drive the generation of DMVs, whereas NSP6 facilitates the curvature and zippering of ER membranes (Fig. 2A, B). NSP6 zippering activity was shown to regulate protein and lipid trafficking to the DMVs, selectively permitting lipid flow while restricting ER luminal proteins access to DMVs, positioning and organising DMV clusters, and mediating contact with lipid droplets through the DFCP1–RAB18 complex6. Moreover, studies have revealed that the NSP6(ΔSGF) mutation, which emerged in multiple variants, exhibits a higher ER-zippering activity, a function possibly linked with the enhanced replication fitness and the increased immune evasion of NSP6(ΔSGF)-bearing variants12. Several models have been proposed for the biogenesis of the DMVs. It is possible that ER membranes pair and bend, forming sheet-like structures, followed by homo-oligomerisation of NSP6 that would ‘close’ this connection, giving rise to ER-linked DMVs. Alternatively, vesicles are thought to detach from the ER and undergo membrane pairing and bending, forming closed DMVs isolated from the ER lumen13.

SARS-CoV-2 remodels the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to facilitate viral replication. Non-structural proteins induce dramatic morphological changes in the ER, including the formation of double-membrane vesicles (DMVs), the site of viral genome replication. A, B Schematic representation of membrane curvature and zippering, leading to the formation of DMVs. C Model depicting the interplay between SARS-CoV-2-induced ER remodelling and UPR activation. The accumulation of misfolded proteins within the ER, a consequence of viral replication and ER stress, triggers the unfolded protein response (UPR). The three main UPR pathways ATF6 (C1), IRE1α (C2) and PERK (C3) are depicted with viral proteins that can directly or indirectly interfere with them.

The synthesis, accumulation, and folding of viral proteins and the formation of ER-derived DMVs trigger a stress response in this organelle, which involves three main signalling pathways mediated by the transmembrane sensors IRE1α, PERK, and ATF6 (Fig. 2C). Physiologically, ER stress response aims to restore ER homoeostasis by increasing protein folding capacity, decreasing protein synthesis, and promoting ER-associated degradation14,15,16. Several studies have demonstrated the overexpression of some unfolded protein response (UPR) factors in SARS-CoV-2 infection, such as GRP78, which is the primary sensor of ER stress17. Indeed, its upregulation is consistently reported both at the mRNA and protein levels in different SARS-CoV-2-infected cell lines. It has also been observed in vivo, with elevated levels of GRP78 detected in lung tissues of COVID-19 patients18. In addition, the knockdown of GRP78 by siRNA and the treatment with its specific inhibitor HA15 decrease the level of S-protein and the production of infectious virions in infected cells19. The expression of GRP78 during SARS-CoV-2 infection appears to be strongly influenced by the highly glycosylated ORF8 since its overexpression increased GRP78 levels leading to the activation of two of the three branches of the UPR: the ATF6 and IRE1α pathways18,20. Co-immunoprecipitation and proximity ligation (PLA) assays on cells overexpressing ORF8 confirmed a robust interaction of ORF8 with GRP78 through its substrate-binding domain and transcriptomic analysis on cells overexpressing ORF8 confirmed a marked upregulation of GRP78 and other ER stress markers, including DERL3 and PDIA4, from 12 to 72 h after transfection21. Recent studies have shown that NSP4, known for its role in modulating host ER membranes during infection, is also involved in GRP78 expression, since cells exogenously expressing a FLAG-tagged SARS-CoV-2 NSP4 construct reveal a significant upregulation of GRP78 transcripts, supporting the hypothesis that it may be involved in the induction of ER stress and subsequent activation of UPR pathways22. Under normal conditions, GRP78 binds to and inhibits the UPR sensors PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6, but the accumulation of unfolded proteins disrupts this interaction, leading to UPR activation23. ORF8 is intriguing in this context, as it can induce UPR pathway activation by directly binding to IRE1α and PERK or competing for binding to GRP7820,24.

IRE1α has endoribonuclease activity and, upon ER stress, cleaves X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA. This results in the splicing and translation of the XBP1s transcription factor, leading to increased gene expression of ER protein chaperones and the translocation and secretion of ER-associated degradation components (ERAD)22,25 (Fig. 2 C2). The role of the IRE1 pathway in SARS-CoV-2 infection is still debated. Early studies state that, unlike other Betacoronaviruses (HCoV-OC43, MHV, MERS-CoV) that fully activate both the kinase and RNase activities of IRE1α, SARS-CoV-2 induces phosphorylation of IRE1α, activating its kinase but inhibiting its RNase activity25. For example, in several cell lines, infection with SARS-CoV-2 led to a significant increase in IRE1α phosphorylation but not a corresponding increase in XBP1 splicing. It has been hypothesised that in SARS-CoV-2 infection, XBP1 regulates the expression of several interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), as evidenced by the decrease in the induction of specific ISGs in IRE1α-KO cells. Thus, to enhance its replication and avoid detection by the host immune system, SARS-CoV-2 infection promotes IRE1α kinase activity but specifically suppresses its RNase activity25. In contrast, more recent studies show significant overexpression of both IRE1α and activated XBP1s in samples from COVID-19 patients26. Upregulation of NUAK2, a critical kinase in the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway, has been observed both in cell culture and in vivo during SARS-CoV-2 infection, and increased NUAK2 levels were shown to facilitate virus entry by increasing the abundance of ACE2 on the cell surface27,28. Like the IRE1 pathway, PERK activation depends on its dissociation from GRP78. In response to misfolded proteins, GRP78 is released and PERK multimerizes and is trans-autophosphorylated. (Fig. 2 C3). The reduction in viral progeny production following inhibition with the PERK kinase inhibitor GSK2656517, suggests its relevance during SARS-CoV-2 infection. SARS-CoV-2 E protein triggers ER stress through PERK-mediated phosphorylation of eIF2α29. Proteomic analysis revealed an increase in both the PERK-ATF4-CHOP and ATF6 pathways in infected cells overexpressing NSP4. Furthermore, co-expression with the N-terminal of NSP3 (NSP3.1) attenuates PERK activation induced by NSP4. This suggests a complex interplay between these two viral proteins in modulating the cellular stress response22. ORF3a has been found to activate the UPR response through the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 pathway in lung epithelial cells. This activation leads to the phosphorylation of eIF2α and the increased translation of ATF4. As a result, it induces the transcription of the pro-apoptotic factor CHOP and contributes to the inflammatory response by activating NF-κB, ultimately leading to the production of various pro-inflammatory cytokines30.

ATF6, the pro-survival factor within the UPR pathway, after its activation following dissociation of GRP78, exposes its Golgi-targeting sequence to be translocated into the Golgi apparatus via COPII-coated vesicles. Proteolytic cleavage within the Golgi releases the transcription factor ATF6-N, which upregulates UPR genes involved in ER folding and ER-associated degradation (ERAD)31 (Fig. 2 C1). Interestingly, it is shown that NSP3.1 directly binds to ATF6 and inhibits its activation, decreasing ATF6 downstream target proteins, such as GRP94 and PDIA4. It is hypothesized that this ability is beneficial for SARS-CoV-2 during infection, potentially preventing the harmful consequences of prolonged UPR activation, such as apoptosis32.

Considering the profound structural and function remodelling induced by SARS-CoV-2 replication on the ER, it is not surprising that several viral proteins have been found to interfere with various steps in the UPR pathway, either by directly binding to key UPR sensors or by modulating the activity of downstream effectors. Such a complex set of strategies is necessary to ensure optimal conditions for viral protein translation, folding and genome replication within the RO, while at the same time evading the innate immune activation and the deleterious consequences of prolonged ER stress activation.

Alteration in autophagy pathway

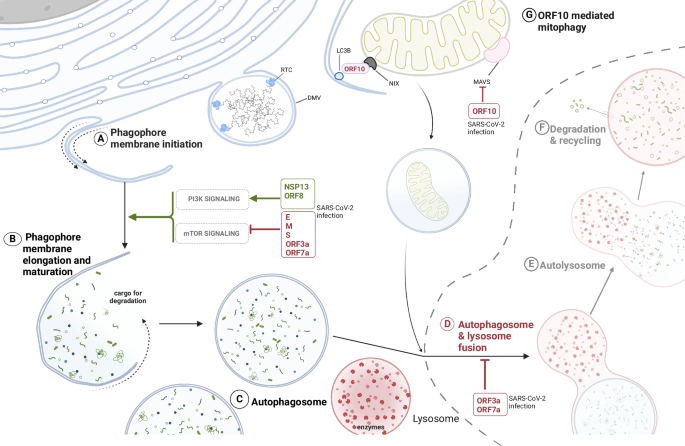

Macroautophagy, further only as autophagy, is a fundamental intracellular process involving the sequestration of redundant or damaged cellular components and pathogens, such as viruses, within double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes. There are two main types of autophagy: general autophagy, which targets non-specific cargo, and selective autophagy pathways, including mitophagy (degradation of mitochondria), ER-phagy (degradation of the endoplasmic reticulum), pexophagy (degradation of peroxisomes), and xenophagy (degradation of extracellular agents). In all cases, the cargo-containing acidified amphisomes merge with lysosomes to enable the degradation of their contents33 (Fig. 3).

SARS-CoV-2 promotes the initiation of phagosomal membranes formation from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes and subsequent autophagosomes accumulation in the infected cell by regulating both the canonical signalling processes to activate autophagy via several of its structural (E, M, S), non-structural (NSP13) and accessory proteins (ORF3a, ORF7a, ORF8) (A–C). The degradative part of the autophagy pathway is impaired thanks to the accessory proteins ORF3a and ORF7a (D–F). These block the fusion of the autophagosome with the lysosome, impairing the lysosomal acidification and, ultimately, inhibiting the degradation of autophagosomal cargo. G ORF10 induces selective degradation of mitochondria (mitophagy) to suppress MAVS signalling and innate immune activation.

Besides maintaining cellular homoeostasis, autophagy is an important player in viral infections, although its impact can vary among different families of viruses. While true degradative autophagy generally tends to have negative outcomes for viral infections, the initiation of non-degradative autophagy, particularly the autophagic membrane formation, can benefit a myriad of viruses33,34,35,36. Viruses with +ssRNA genome, such as SARS-CoV-2, replicate in the cytoplasm and require the formation of membranous replication organelles, therefore co-opting the induction of autophagosomal membrane formation can be beneficial31.

In fact, it was reported that SARS-CoV-2 closely interacts with different autophagy pathways34,37,38,39. Several viral proteins, such as E, M, S, ORF3a and ORF7a, induce autophagosomes accumulation in infected cells as they stimulate early autophagy by negatively regulating the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signalling (Fig. 3). Interestingly, even if ORF3a increases the nuclear localisation of TFEB (transcription factor EB) which regulates lysosome biogenesis, it only leads to the upregulation of genes for cathepsin D and cathepsin A, while most of the other TFEB-regulated genes stay unaffected37,40,41. Overexpression of SARS-CoV-2 ORF7a protein activates autophagy through the AKT-mTOR-ULK1-mediated pathway and it is important for the production of viral progeny, as demonstrated with decreasing viral titres upon use of small hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting ORF7a42. Also, the structural protein spike induces autophagy by the same pathway as ORF7a, as Spike inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling by upregulation of reactive oxygen species in the cell43. Class I phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) activation in SARS-CoV-2 infected cells was shown as necessary for viral replication organelles formation34. SARS-CoV-2 subsequently inhibits late autophagy and autophagic flux thanks to the ORF7a and ORF3a, where the interaction of ORF3a with the lysosomal protein VPS39, a homotypic fusion and protein sorting (HOPS) complex component, blocks the assembly of the STX17-SNAP29-VAMP8 SNARE complex whose formation is necessary for autophagosome/amphisome-lysosome fusion, which results in further accumulation of autophagosomes41,44 (Fig. 3). ORF7a supports the block of autophagosome-lysosome fusion by decreasing SNAP29 in a CASP3 activity-dependent manner42. Accordingly, SARS-CoV-2 impairs ER-phagy via the interaction of ORF8 with the adaptor protein p62 resulting in the formation of liquid droplet condensates to recruit ER-phagy receptors FAM134B and ATL3. This further causes ER stress and is hypothesised to help viral NSPs hijack ER membranes for DMVs formation, while preventing the degradation of their ER-originating membranes45. Pharmacological activation of autophagy or targeting of viral ORFs responsible for autophagosome-lysosome fusion impairment counteracts the virus propagation39,42.

Thus, while conventional macroautophagy might be dispensable for the virus, the non-canonical autophagic processes and early autophagy machinery seem indispensable46,47. Activation of non-canonical autophagy-like processes led to the formation of double-membrane vesicles, phagophores, and phagosomes inside the infected cells. Koči et al. showed in the VeroE6 cellular model that the upregulation of several autophagy-related factors, such as ATG3, ATG16L1 and UVRAG occurs during SARS-CoV-2 infection and speculate it might be important for virus replication as they observe virus particles close to phagophore membranes47. The KO of autophagy factors VMP1 and TMEM41B is detrimental to vROs formation as VMP1 regulation of phosphatidylserine distribution in host membranes might enable the proper closure of the viral double-membrane vesicles and TMEM41B facilitates the NSP3-NSP4 interaction48.

SARS-CoV-2’s multifaceted interaction with the autophagy pathway is also evident from virus evasion of the antiviral innate immune response through rewiring selective autophagy processes. To counteract the innate immunity, the accessory protein ORF10 induces mitophagy through the interaction with the mitophagy receptor Nip3-like protein X (NIX), which leads to microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta (LC3B) recruitment on the mitochondrial membranes and to the degradation of the mitochondrial antiviral signalling proteins (MAVS) (Fig. 3). MAVS degradation suppresses the type I interferon (IFN-I) signalling and impairs the expression of IFN-I genes and IFN-stimulated genes49. ORF10 additionally inhibits the activation of CGAS‐STING1‐IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)‐TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and its interaction with STING, which further attenuates IFN response50. Similarly, also SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 evades the host antiviral response by degrading TBK1 in complex with p62 in a p62-dependent selective autophagy, and likewise ORF10, it inhibits the IFN-I signalling51. Another example of SARS-CoV-2 exploiting autophagy-driven degradation of innate immune effectors is ORF8, which is able to downregulate the major histocompatibility complex class Ι (MHC-Ι) via its targeting into lysosomes in an autophagy-dependent manner, resulting in lower antigen presentation and thus hindering the recognition of infected cells by T cells52. Finally, modulation of autophagy has important consequences on SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis in vivo since it was shown that autophagy is dysregulated in peripheral lymphocytes of COVID-19 patients, promoting their apoptosis and leading to lymphopenia in COVID-19 patients53.

Thus, it is clear that the autophagy pathway is crucial for the SARS-CoV-2 considering the profound modulation affecting this pathway during viral infection, with the first part of the pathway benefiting virus replication as the initiation of autophagy, LC3 accumulation and the presence of some canonical autophagy activators promotes viral DMVs formation as well as the production of infectious viral progeny, while the maturation of autophagosomes and complete autophagy flux proven to be unessential and potentially detrimental for the infection. However, many aspects remain unclear in whether and by which mechanism the virus usurps some of the autophagy factors for its own benefit or which selective autophagy pathway is necessary for the infection. Therefore, further investigation of the virus-autophagy crosstalk is required.

SARS-CoV-2 infection rewires host lipid metabolism

Cellular membranes are mainly formed by lipids and their composition, amounts and proportions influence membrane biophysical properties such as curvature and fluidity. Several studies have demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 profoundly manipulates host lipid metabolism at the organism level, with the accumulation of lipids such as polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) representing robust biomarkers of severe disease outcomes54. Indeed, a robust supply of lipids is required to sustain the formation of DMVs and the assembly of novel virions. However, viral infection not only alters lipid levels but also affects their intracellular distribution.

Lipidomics revealed that SARS-CoV-2 replication leads to global changes in lipid species, which are conserved among different viral strains and cell types, suggesting that infection pilots lipid composition in a defined direction (Table 1). For example, ceramides, which belong to the family of sphingolipids, are upregulated during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Using viral particles pseudotyped for Spike protein, it was found that the interaction between spike and ACE-2 at the cell membrane, triggers the acid sphingomyelinase (ASM), which synthesises ceramides. This leads to the formation of ceramide condensates in a receptor-dependent manner (Fig. 1). Consistently, genetic perturbation and pharmacological inhibition of ASM by Fluoxetine, Maprotiline and Amitryptiline blocked viral entry into epithelial cell lines and primary human nasal epithelia, and supplementing cells with C16 ceramide rescued infection levels55,56.

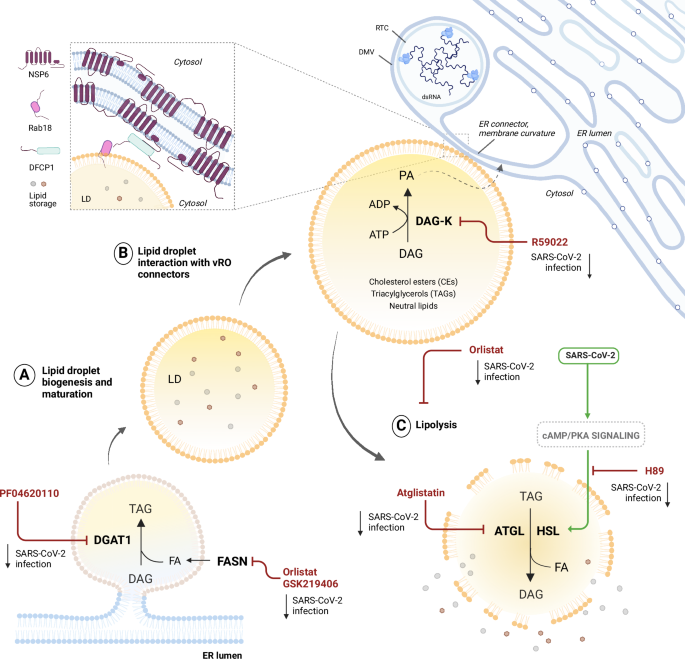

Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 in vitro upregulates the biosynthesis of triacylglycerols (TAGs) bearing PUFA groups. The same trend is observed for the phospholipids class, with an overall decrease in saturated and mono-unsaturated species of phosphatidylcholines (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) and a significant increase in phospholipids bearing PUFA (Table 1). This reinforces the idea that SARS-CoV-2 requires high membrane fluidity for membrane rearrangements, although which lipid species accumulates within the viral ROs, how they change and from which compartments they derive along the course of the infection is still poorly understood57. Lipidomics on DMVs performed for other +ssRNA viruses, such as HCV, showed an accumulation of phosphatidic acid (PA), a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of glycerophospholipids (Fig. 4). A similar accumulation of PA was observed on SARS-CoV-2 vROs. By inhibiting AGPAT-1, DAGK, or PLD1, all factors involved in PA synthesis, the biogenesis of vROs for both SARS-CoV-2 and HCV was impaired, suggesting that PA represents an essential dependency factor for viral replication, probably by promoting membrane curvature required for DMVs formation38.

SARS-CoV-2 exploits lipid droplets (LDs) biogenesis and consumption to fuel viral replication LDs increase in size and number in the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection, then they are consumed to liberate fatty acids (FAs). A Inhibition of LDs biogenesis mediated by DGAT1 and FASN reduces SARS-CoV-2 replication. B Interaction between mature LDs and viral replication organelles (vROs) is mediated by DFCP1 and NSP6, respectively, at the ER connectors. C Inhibition of lipolysis mediated by ATGL and HSL reduces SARS-CoV-2 replication. Lipolysis is crucial in infection, since SARS-CoV-2 activates cAMP/PKA signalling.

Moreover, the sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) pathway has been identified as a critical regulator of Coronaviridae and Flaviviridae infections, with viral replication being less efficient in a poor cholesterol environment. This pathway is activated by sterol sensing mediated by SCAP and the protease MBPTS1, previously described as promoters of pan-coronaviral infection. These factors proteolytically activate SREBP transcription factors in the ER, which in turn activate cholesterol biosynthesis58,59. Indeed, silencing of SREBP2 decreases SARS-CoV-2 titres, although the exact step of the viral life cycle impaired by low cholesterol levels has not been elucidated yet. A similar requirement of SREBP-mediated lipogenesis was also observed for SARS-CoV60. Not only cholesterol biosynthesis, but also its transport turned out to be beneficial for SARS-CoV-2 productive infection, since the knock-down of the transporter NPC2 revealed a strong antiviral effect58.

It has been widely demonstrated that cholesterol plays a major role early in SARS-CoV-2 infection during the entry step and at later stages for cell-cell fusion to form syncytia. In particular, SARS-CoV-2 stimulates the expression of the ISG cholesterol 25-hydroxylase (CH25H), which synthesises 25-hydroxycholesterol (25HC). 25HC is able to block the entry of SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV pseudoparticles, by activating acyl-CoA cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT), which sequesters cholesterol from the plasma membrane, further promoting the storage of cholesterol esters (CEs) species in LDs61.

The role of LDs has been widely explored in +ssRNA viruses replication, since such pathogens dynamically modulate LDs in terms of size and number62,63. LDs can serve as scaffolds for viral assembly or fatty acid sources, as for HCV and dengue virus64. Also in the case of SARS-CoV-2, some reports suggest a potential role of LDs as assembly and trafficking platforms for mature viral particles65. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, LDs increase in number and are partially recruited at vROs thanks to NSP6 which acts as a tether between the two compartments and channels LD-derived lipids to the vROs (Fig. 4). This results in LDs consumption upon vROs formation6. Besides a structural involvement of LDs, compound screenings revealed a prominent metabolic role of such organelles in SARS-CoV-2 life cycle: viral replication is reduced by PF04620110 treatment, which impairs the storage of TAGs in LDs by depleting DGAT-1 function, thus LDs formation (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, inducing LDs accumulation does not seem beneficial for viral fitness: infections in the presence of Orlistat, a non-specific inhibitor of lipolysis and fatty acid synthase (FASN) and GSK219406, a specific inhibitor of FASN, led to a significant decrease in SARS-CoV-2 replication despite the increase in LDs biogenesis57 (Fig. 4). These data were also confirmed in the chronic depletion of FASN in Caco2 KO cell lines, in which SARS-CoV-2 replication was impaired at a post-entry level66. Among the potential multiple roles of FASN in infection, one of the most relevant is the biosynthesis of palmitate, a 16-carbon fatty acid that is conjugated to the spike protein during SARS-CoV-2 protein maturation and assembly67. Upstream of FASN, also acetyl-CoA carboxylase-α (ACACA) seemed critical for viral replication, being a rate-limiting enzyme of de novo FA biosynthesis68.

In this respect, recent findings claim for a role of LDs in the late stages of SARS-CoV-2, as well as influenza A virus, life cycle. As previously stated, LDs biogenesis and consumption are dynamic processes, and these organelles are massively consumed by SARS-CoV-2 in the late stages of infection6,69. LDs breakdown is exerted by adipose-triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL). The resulting liberation of free fatty acids (FFAs) was found to be a limiting step during late stages of infection (Fig. 4). Consistently, viral infection up-regulates the cAMP/PKA signalling pathway, leading to increased pHSL levels and thereby lipolysis70. Moreover, blocking ATGL with Atglistatin, or cAMP/PAK with H89, dramatically decreased SARS-CoV-2 cytopathogenesis both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 4). One possible explanation relies on the innate immune response since LDs can regulate the induction of TNF-a, IL-6 and the eicosanoid storm, thus promoting reversible cellular damage when lipolysis is pharmacologically inhibited69. Recently, some light has been shed on how LDs and the innate immune response are linked for +ssRNA viruses64,65. Thus, considering their multifaceted role, from metabolism to immunity, it is not surprising that LDs have such a critical role during SARS-CoV-2 and, more generally, during +ssRNA virus infections.

Conclusion

In this review, we highlight the intricate mechanisms employed by SARS-CoV-2 to exploit host cell organelles and pathways, creating a favourable environment to replicate and spread as well as the mechanisms put in place by the cell to fight the viral infection. The web of interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and its host encompass numerous different pathways and processes, creating an intricate network that can further change according to the cell type and organism used, the time of infection and the viral variants. Thus, we decided to untangle only some selected molecular processes and pathways that are ultimately linked, in a way or another, to the process of formation of viral replication organelles, leaving out other important aspects, such as the innate immune evasion strategies, that have been extensively covered in recent reviews71,72. The global effort put in place by scientists during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has provided unprecedented insights into the host-pathogen interactions, not only of the Coronaviridae but also for other +ssRNA viruses, revealing how evolutionary distant viruses have evolved similar strategies to rewire and exploit metabolic processes and pathways of the host. This is especially true for the complex process that leads to the biogenesis of the viral replication organelles, a critical step for the successful replication of all +ssRNA viruses, which requires an intricate interplay between viral and cellular factors. In conclusion, further studies are still required to grasp the complete spectrum of interactions occurring between the virus and its host, and the consequences that those interactions have on viral pathogenesis and disease.

Responses