A prospective study to investigate circadian rhythms as health indicator in women’s aging

Introduction

In mammals, the timing of physiological and cellular processes is regulated by an internal time-keeping mechanism known as the circadian clock1, which allows for optimal adaptation to external cues and environmental changes, such as day/night cycles. The circadian system includes a master pacemaker located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), that synchronizes peripheral clocks within every cell of the body2. The circadian clock orchestrates 24-hours (h) rhythmic phenotypes in a wide range of cellular and physiological processes, including the cell cycle, metabolism, immune system functioning or blood pressure, and sleep-wake cycles3. At the molecular level, circadian oscillations are generated via a transcriptional-translational feedback loop (TTFL) where positive elements (BMAL1/CLOCK) directly drive the transcription of negative elements (PER/CRY), which in return inhibit their own transcription4. Further fine-tuning of BMAL1 occurs through the opposing effects of RORA/B/C and NR1D1/2.

Disruptions of the circadian clock are a major characteristic of aging and relate to disruptions in sleep patterns, metabolism, and cognitive function5,6. Aging is associated with alterations in circadian parameters. The amplitude is reduced, while the circadian phase tends to occur earlier7. Moreover, circadian disruptions have been implicated in various pathologies, including cancer8, cardiovascular, and metabolic disorders9, which are also more prevalent with aging.

Circadian rhythms characteristics are specific to the biological sex. Such differences can be due to various factors, including hormonal variances between males and females. In a study under a controlled environment, the circadian phase measured via melatonin, and core body temperature rhythms in women was reported to peak earlier as compared to men10. In addition, hormonal influx among women can significantly influence circadian rhythms throughout different stages of life, which might explain the increased incidence of circadian alterations during aging among females as compared to males11. Cognitive and mood impairments associated with circadian dysregulation are more extreme in women due to alterations in the hormonal influx12. Females also report a higher prevalence of insomnia and anxiety-associated disorders as compared to males11. Aging among women is associated with a naturally occurring physiological event named menopause, the principal characteristic being the cessation of fertility and reproduction13. Most women experience these hormonal changes between their mid-40s to mid-50s. During menopause, the ovaries alter their function so that the course of the menstrual cycle changes and periods eventually stop. After the last menstrual period, it typically takes a few years for the hormonal processes to stabilize. With the onset of menopause, the alterations in sleep patterns which are directly linked to the circadian clock, increase among women, thereby affecting their quality of life14. Moreover, women are at higher risk of severe chronic diseases like obesity, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis during menopause15. The occurring hormonal changes directly influence liver health as estrogen plays a major role in several metabolic processes including liver fat metabolism and insulin sensitivity16. Several dietary changes are recommended to minimize the symptoms of menopause, and to promote longevity among women15. Data from the Pittsburgh Women’s Healthy Life Project suggests that following a 1300 kilocalorie (kcal)/day hypocaloric diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol during menopause can prevent weight gain over a 4.5-year follow-up17. Similarly, the Women’s Health Initiative trials found that adopting a low-fat diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and grains, without focusing on caloric restriction, also helps prevent weight gain in postmenopausal women18. Furthermore, an anti-inflammatory diet can help reduce the chronic inflammation within the body, which is associated with various health problems in women during menopause. For example, the application of the Mediterranean diet, which can contribute to reducing inflammation in the body, is beneficial for the overall health of women during menopause19. Thus, changes in lifestyle and different environmental factors can directly influence circadian rhythms. Growing evidence points towards a bi-directional interplay between metabolism and the circadian system20.

Understanding the molecular alterations in circadian rhythms associated with aging and menopausal transition in women is vital for developing strategies to support healthy aging and minimizing the side effects of menopause. It remains unknown whether specific dietary recommendations, especially an anti-inflammatory diet, can help to minimize the alterations in circadian rhythms and improve, for example, sleep quality.

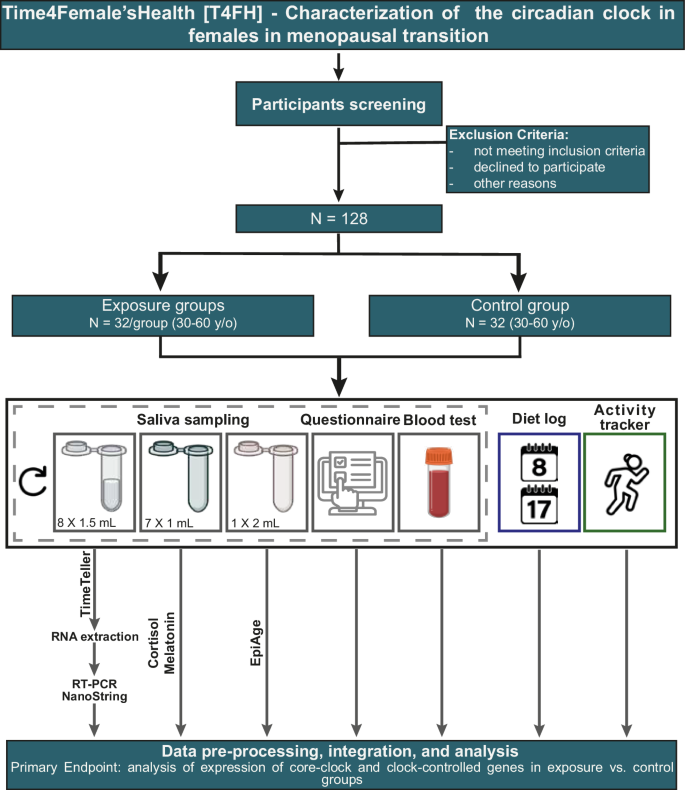

In this study, we aim to characterize: (1) circadian clock alterations in healthy women undergoing menopausal transition (age ≥ 30–60 years old (y/o)), and (2) whether such alterations can be compensated by a nutritional exposure (a. specific dietary regime (anti-inflammatory diet); b. time-of-the-day-dependent light exposure; c. anti-inflammatory diet plus light exposure) for 21 days. Using a non-invasive circadian clock monitoring approach21, we will characterize and monitor the gene expression profile of core-clock genes (e.g., BMAL1, CLOCK, PER1, PER2, NR1D1, and NR1D2) and aging-associated genes (e.g., SIRT1, FOXO1, FOXO3, IL6, MTOR, TP53, IGF1). We will further evaluate output parameters related to the clock behavioral phenotype, daily habits, and additional data via standardized questionnaires such as resilience, quality of life, chronotype evaluation, sleep quality, nutritional intake, and menopause rating scale, to explore possible correlations of alterations in these parameters and circadian variations measured via expression of the above-mentioned genes.

In addition, given that women experience changes in melatonin and cortisol levels during the hormone imbalance, we aim to measure melatonin and cortisol levels. Finally, we will also integrate epigenetic data (EpiAge), and collect activity tracker data. This holistic approach will help us gain insights into menopause-associated symptoms and support the development of strategies to improve well-being during menopause.

Discussion

This study aims to investigate the complex relationship between circadian rhythm alterations in aging, particularly during menopause, and their implications for female health and associated symptoms.

As women transition through menopause, a significant biological event leading to the cessation of menstruation, hormonal fluctuations profoundly impact circadian rhythms. Estrogen, a key hormone, regulates various physiological processes, including sleep-wake cycles22, mood regulation23, and thermoregulation24, all of which are related to circadian rhythms. During menopause, declining estrogen levels disrupt the delicate balance of these processes, leading to alterations in sleep patterns, mood disturbances, and vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes and night sweats.

Circadian rhythm related disturbances are commonly observed in menopausal women, with reports of increased sleep onset latency, frequent awakenings during the night, and overall poorer sleep quality25. These disruptions are often attributed to changes in hormonal signaling, particularly alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the regulation of melatonin secretion. Menopausal changes in estrogen levels can disrupt melatonin synthesis and secretion, contributing to sleep disturbances commonly reported during this transitional phase26.

Furthermore, the circadian regulation of body temperature is closely linked to menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes and night sweats. Fluctuations in estrogen levels can dysregulate the thermoregulatory system, leading to sudden and intense sensations of heat27. These vasomotor symptoms often occur during the night, disrupting sleep and further exacerbating circadian rhythm disturbances. The bi-directional relationship between disrupted sleep and vasomotor symptoms creates a cycle of sleep deprivation and hormonal dysregulation, ultimately impacting overall health and quality of life in menopausal women25. In addition to sleep disturbances and vasomotor symptoms, menopausal women may also experience mood disturbances, including depression, anxiety, and irritability28. Circadian rhythm disruptions, characterized by alterations in the timing and duration of sleep, can exacerbate these mood disturbances, further compromising mental health and well-being. Moreover, changes in circadian rhythms can impact cognitive function and contribute to age-related cognitive decline in menopausal women29.

Altogether, the consequences of dysregulated rhythms are strongly associated with menopause-related symptoms and negatively impact the health and life quality of females. Results from this study will contribute to a better understanding of such circadian dysregulations and their health implications. The above-discussed findings underscore the complex interplay between circadian rhythms, hormonal fluctuations, and menopausal symptoms, highlighting the need for comprehensive management strategies tailored to the unique needs of menopausal women. Interventions targeting circadian rhythm disturbances, such as nutritional exposure, light exposure, physical activity, and proper sleep hygiene, may offer promising avenues for alleviating symptoms and improving overall health outcomes in this population.

Overall, a deeper understanding of the intricate relationship between circadian rhythms and menopause is essential for developing targeted interventions to mitigate symptom burden and optimize health outcomes in menopausal women. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving circadian rhythm disturbances during menopause and to evaluate the efficacy of novel interventions in ameliorating associated symptoms and improving quality of life.

Methods

Objectives

The main hypotheses to be addressed in this study are:

-

1.

Daily habits modifications including light exposure or specific diets via for example an anti-inflammatory diet during menopause impact circadian rhythms, measurable in the circadian profiles of the core clock and likely clock-controlled genes that are associated with aging in women.

-

2.

Environmental and dietary factors directly influence epigenetic modifications and circadian rhythms in menopausal women.

-

3.

Quality of life and resilience levels are positively associated with improved robustness of circadian rhythms and overall health outcomes.

-

4.

Optimized daily routines, including sleep and activity patterns, synchronize and enhance circadian rhythms in women, leading to improved health outcomes.

Ethical approval

All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the ethical committee at the MSH Medical School Hamburg (MSH-2023/297). Recruitment started in December 2023 and will take place until the end of 2026. There are no risks or burdens for the study participants. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations including the Declaration of Helsinki and the ICH good clinical practice guidelines. Written informed consent will be obtained from all recruited participants.

Study design

This study is a prospective non-randomized cohort study of females in the menopause transition phase in Germany, investigating the impact of nutritional and light exposure i.e., an anti-inflammatory diet course for menopause (AIDM) on circadian rhythm, and quality of life. The study will include participants aged 30–60 y/o, with 32 participants recruited per group. Participants interested in the study will be allocated as follows, based on the type of exposure: those who sign up for the AIDM and adhere to the specific dietary changes will be assigned to the AIDM group, or to the AIDM and circadian recomendations group, or to the circadian recomendations group. Those who are aware of the course, but do not sign up or do not carry out dietary changes will be assigned to the control (no exposure) group. This study will take place from 2023 to 2026 and aims to (1) characterize circadian rhythms in females during menopause; and (2) evaluate the effectiveness of nutritional and behavioral exposure in improving the robustness of circadian rhythms and a potential correlation with health parameters of the participants. Participants will be recruited from the pool of those interested in the AIDM, which is a nutritional exposure (https://nobodytoldme.com/body-reset-kurs-von-nobodytoldme/) designed to minimize and manage the symptoms of menopause and with more than 8,000 registered females with an average age of 51 y/o, who wish to reduce menopause-related symptoms. Participants who sign up for the anti-inflammatory diet course, and without a history of chronic illness, adhere strictly to it for 21 days, will be recruited for the AIDM group, or AIDM and circadian recomendations group. The control group will consist of age-matched participants without a history of chronic illness or insomnia and who do not follow any strict diet regimen. The study participants from the subgroup “AIDM group” (n = 32) will collect saliva samples before and after the end of their course, the same procedure will be taken for the circadian recomendation group. The age-matched controls (n = 32) will not participate in the AIDM and will carry out saliva sampling both before and after approximately 21 days (Fig. 1). To mitigate the impact of seasonal variation on the circadian profile, participants will be recruited at different times of the year. Study documents and material required for the saliva sampling will be sent to the study participants by post and sampling will be carried out at home. Samples will be sent by the participants using the enclosed pre-paid package to our lab at the MSH Medical School Hamburg for analysis.

Saliva sampling will be carried out to quantify clock gene expression, cortisol and melatonin, and epigenetic age. Gray boxes represent the data that will be collected before and after the AIDM course exposure (AIDM group) or before and after ~ 21 days (controls). The blue box represents the data that will be collected on Day 8 and Day 17 of the AIDM course. The green box represents the data that will be collected at the end of the study (y/o: years old; RNA: ribonucleic acid; RT-PCR: reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Participants of this study will be recruited via an online announcement shared with the pool of interested participants in the AIDM course via the platform nobodytoldme (https://nobodytoldme.com/body-reset-kurs-von-nobodytoldme/). An information sheet with the study details will be shared with potential participants. Upon positive feedback from interested participants, questions will be clarified during an online information session, and a written informed consent form will be shared for signature.

Participation in the study is voluntary. Participants must sign the consent form before study initiation and documentation of any study-related tests or procedures. Study participants are females, adults (>18 y/o), non-smokers, willing to carry out saliva sampling multiple times, and have a good understanding of the study-related instructions described below. In addition, participants will be asked about their health status at the time of recruitment, i.e., their physical, mental, and social well-being. An increase in blood pressure may occur during menopause, therefore, participants with high blood pressure will not be excluded from this study. Furthermore, estrogen deficiency with menopause can increase the risk of developing hypothyroidism, including Hashimoto’s disease30. These pathologies will therefore not be used as an exclusion criterion, as long as participants can continue their normal lives. Withdrawal from the study can take place at any time and is the sole decision of the participant.

Participants who do not consent to participate in the study or are pregnant will be excluded. Further exclusion criteria include the presence of an acute oral infection.

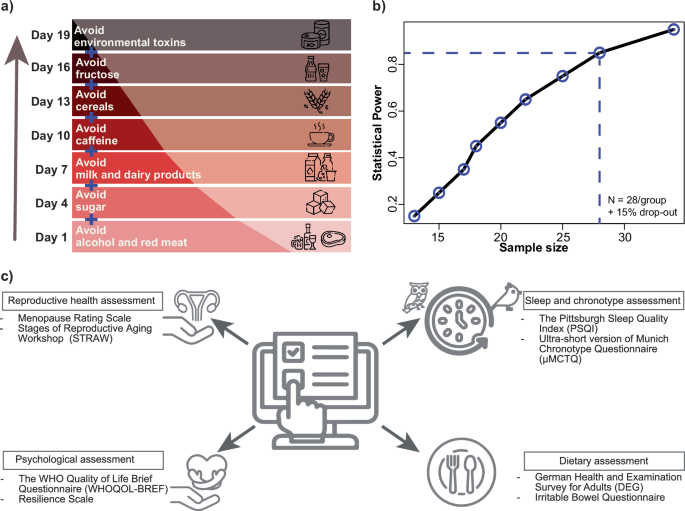

Anti-inflammatory diet course for menopause (AIDM)

The diet used (an anti-inflammatory diet; https://nobodytoldme.com/body-reset-kurs-von-nobodytoldme/) aims to minimize the side effects of the menopausal transition and to promote healthy living in women. In this course, women gradually change their diet based on previously reported findings31,32. The AIDM aims to allow for a sustainable, change in women’s diets through several online sessions and a digital guidance portal to alleviate menopause-related symptoms (Fig. 2a). Participants in the AIDM group will adhere to the dietary changes for 21 days, as in the course. Their adherence will be monitored through online sessions and during 24-h protocols on Day 8 and Day 17 of the AIDM exposure, where each participant will be asked to provide detailed information on what they ate and drank throughout the day.

a Depicted are the sequential dietary changes for participants in the AIDM group, in addition recommendations regarding optimal light exposure throughout the day will be provided. b Line plot represents the estimated sample size per group based on power = 0.85, α = 0.001, and r = 1.44. c Description of the self-assessment questionnaires. Participants will fill in compiled digital surveys via the REDCap tool for assessment of sleep and chronotype; diet; reproductive health status and overall well-being such as quality of life and resilience (WHO: World Health Organization).

Caffeine consumption can significantly disrupt sleep, even when consumed 6 h before bedtime33. Caffeine can alter sleep stages, increasing light sleep and decreasing deep sleep in male and females, particularly when consumed later in the day34. Caffeine will be avoided by women undergoing AIDM with sleep problems undergoing menopause transition due to several factors. Poor sleep quality was associated with consuming high-energy drinks and high-calorie coffee drinks in adult women, which contain both caffeine and sugar35. Additionally, caffeine intake may hinder calcium absorption, negatively affecting bone mineral density, which is a concern for the postmenopausal women when the risk of osteoporosis rises36. Furthermore, caffeine can aggravate anxiety and mood swings, which are common during menopause due to hormonal fluctuations. Although, in another study older females who abstained from caffeine reported more sleep disturbances and had greater odds of short sleep duration compared to those who consumed caffeine37. This suggests a complex relationship between caffeine and sleep in women from different age groups. Even though it is not one of the aims of this study to clarify this particular point, we will collect information on the amount and time of caffeine consumption.

Circadian recommendations

During the study, participants will be given the following light exposure recommendations to help optimize their circadian rhythms:

-

1.

Morning Light Exposure: Participants should aim to get natural sunlight exposure within the first hour after waking up, as this helps regulate the sleep-wake cycle and enhances alertness during the day.

-

2.

Limit Evening Light: To improve sleep quality, participants should avoid bright and blue light exposure, particularly from screens, at least 1–2 h before bedtime. This can be achieved by dimming lights or using blue light filters on electronic devices.

-

3.

Consistent Light Schedule: Participants should maintain a consistent daily light exposure schedule, even on weekends, to strengthen their circadian rhythm and promote stable sleep patterns. In case of insufficient natural light exposure, especially in winter months, exposure to bright white or blue light in the morning can be recommended to help regulate the circadian cycle.

These strategies can be tailored to individual schedules and environmental conditions to support optimal circadian function throughout the study period, and will be discussed with the participants, according to their exposure type group.

Sample size estimation

To estimate the number of participants needed for this study, we used expression data for BMAL1 among healthy females reported in our previous study38. In this study, the active sampling design (evenly spaced saliva sampling time i.e., participants will be informed to carry out their saliva sampling at specific times of day) will be followed. Based on BMAL1 gene expression data, an average amplitude (A) of 1.606 and a standard deviation of the residuals (s) of 1.113 were observed, resulting in the intrinsic effect size (r) = A/s = 1.44. Afterward, the sample size was estimated per group based on the intrinsic effect size, significance level (α) at = 0.001, and power of 0.85. Based on the analysis, 32 participants (128 in total considering the 15% drop-out rate) per group are required (Fig. 2b).

The sample size is estimated based on the R package CircaPower39 where the model assumes that measurements follow a sinusoidal wave function for a given sample i (1 ≤ i ≤ n, n is the total number of samples) as depicted in (1).

where yi = gene expression values at a specific time ti; ϵi is the error term for sample i; M is the MESOR (Midline Estimating Statistic Of Rhythm, a rhythm-adjusted mean); A is the amplitude; ϕ is the phase shift, and ω is the frequency of the sinusoidal wave i.e., ω = 2π/Period (where period, in this case, is 24 h).

Data collection

Participants from both the control and exposure groups will provide saliva samples to assess their circadian rhythms, hormonal changes (melatonin and cortisol), and epigenetic age (EpiAge). Additionally, all groups will be asked to complete self-assessment questionnaires at two time points: before and after the AIDM course exposure for the AIDM and AIDM plus circadian recomendations groups, and before and after approximately 21 days for the circadian recomendations, and control groups.

Saliva sample collection for circadian rhythms evaluation

Study materials will be sent to participants via mail prior to the start of the study. Participants will receive a set of two home test kits for profiling of circadian rhythms based on saliva sample collection (TimeTeller®, Hamburg, Germany) and return the collected samples per post to the study team. Up to 1.5 mL of saliva is required per tube (indicated on the tube). On the day of sampling, the study participants can follow their normal daily routine. A total of 8 saliva samples should be taken on two consecutive days (Day 1: 9 h, 13 h, 17 h, 21 h; Day 2: 9 h, 13 h, 17 h, 21 h). To avoid possible interference with the sampling, the participants will be asked to refrain from eating/drinking 30 min before the saliva sampling. The participants will be advised not to brush their teeth or use mouthwash before sampling. Participants belonging to the exposure groups will carry out saliva sampling before (preferably the weekend before the AIDM course starts) and after the AIDM course (preferably the weekend directly after). Whereas, age-matched controls will be asked to provide two sampling kits within a gap of ~21 days. Participants from the exposure-groups will be divided into three sub-groups: (1) AIDM alone; (2) circadian recommendations (e.g., light exposure) alone; and (3) AIDM along with circadian recommendations.

Saliva sample collection for hormonal assessment

We will collect a single night-time melatonin measurement from participants directly before their usual bedtime. Should, during the time of the study, robust test for continuous at home melatonin assessment be available we will consider using those. While this approach has limitations compared to continuous monitoring, it provides a practical proxy for melatonin presence and timing relative to the sleep-wake cycle in large-scale, at-home studies. To supplement this data, we will also collect morning cortisol measurements, as the interplay between melatonin and cortisol reflects overall circadian rhythm integrity. Additionally, participants will complete questionnaires regarding their bedtime routines and home light conditions to provide context for interpreting the melatonin results. For cortisol and melatonin measurements, the participants will be provided with home-based test kits (Cerascreen®, Hamburg, Germany). For melatonin testing, participants will collect 1 mL of saliva directly before going to bed. For cortisol testing, participants will collect saliva at seven time points depending on their wake-up time (directly after waking up; 30 min; 1 h; 2 h; 5 h; 8 h; and 12 h after waking up). To avoid possible disturbances during the sample collection, the participants will be advised to refrain from eating/drinking 30 min before the saliva collection. Moreover, participants are advised not to brush their teeth or use mouthwash before the saliva sampling.

Saliva sample collection for epigenetic analysis

To examine whether the epigenetic age of the participants shows differences before and after the exposure, an additional saliva sample will be carried by the participants to determine their epigenetic age. In addition, the age-matched controls will also carry out the epigenetic age test before and after ~21 days. All participants will be asked to carry out saliva sampling for epigenetic age evaluation at the same time (11 h) to minimize the time-of-day influence. Participants will be provided with home-based epigenetics (EpiAge, Munich, Germany) test kits and participants will be asked to refrain from any collagen-based supplements and will be recommended to collect 2 mL of saliva for the test at 11 h. The epigenetic age via EpiAge kit is measured through the evaluation of 13 methylation sites of ELOVL2, one of the robust biomarkers for epigenetic age evaluation40.

Activity tracker data collection

During the first round of recruitment, the participants will be provided with a fitness tracker (smartwatch) that records their heart rate, activity, and sleep-wake cycles. Participants will be asked to wear the smart tracker for at least one day before starting the saliva sampling and throughout the entire duration of the study. Participants will be provided with a step-by-step manual prepared by the study team to set up the tracker and export the data post-saliva sampling. Based on the willingness of participants to share the activity tracker data (either of the provided fitness watch or an equivalent device regularly used by the participants), a secured link will be provided for data sharing using the University servers. Upon study completion, participants may keep the smart tracker.

Self-assessment questionnaires

Questionnaires and medical history will be collected in electronic case report form (eCRF) format distributed via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) to preserve the protected flow of personal information41. Participants will be asked to fill out the questionnaire at least twice (before and after the exposure or before and after ~ 21 Days). Self-designed anamnesis will be used to obtain information on the presence of known chronic or acute diseases, concomitant medications, or long periods of sickness. Additional questions were compiled from different questionnaires, and can be divided into four groups, all of which are relevant to our study objectives:

-

1.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)42 questionnaire will be used to assess the sleep quality among healthy females. The results are categorized into “poor” or “good” sleep category based on subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, sleep medication use, and daytime disturbance in the last four weeks. µMunich Chronotype Questionnaire (µMCTQ)43 will be used to assess the chronotype of the study participants. This questionnaire is an ultra-short version of the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire.

-

2.

The German Health and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS) questionnaire44 will be used to assess the nutritional changes. The DEGS food frequency questionnaire is used to calculate the “Healthy Eating Index (HEI)” and to investigate whether the nutritional exposure leads to an improvement in the HEI45. To confirm adherence to the AIDM vs. controls, participants will be asked to complete a 24 h dietary recall on day 8 and day 17 of the AIDM course. The Irritable bowel questionnaire46 (German version named as Reizdarmfragebogen, RDF) will be used to assess the individually perceived changes related to the gastrointestinal system.

-

3.

The Menopause Rating Scale47 will be used to assess the severity of menopausal symptoms. Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW)48 to assess the reproductive aging stage of each participant.

-

4.

The WHO Quality of Life Brief Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF)49 assesses the quality of life by focusing on four domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and the surrounding environment. The Resilience Scale50 assesses the ability to cope with and recover from adverse events.

Liver health examination

To assess liver health, non-invasive liver fibrosis risk scores (e.g., Fibrosis 4 (FIB-4) index or Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score(NFS)) will be measured by collecting information on age, weight, height, and diabetes (yes/no). Participants would be asked to decide voluntarily for self-determined laboratory parameters, including (Aspartate Aminotransferase (GOT/AST), Alanine Aminotransferase (GPT/ALT), platelets count, and albumin, which can be determined at an external laboratory before and after the end of the AIDM and circadian recommendations.

Experimental analysis

The aim is to analyze the gene expression profile of at least 6 – 10 clock genes and aging-associated genes (e.g., BMAL1, PER, CLOCK, NR1D1/NR1D2, SIRT1, IGF1, TP53, FOXO1/ FOXO3, PDHB, IL6, MTOR), should the quantity and quality of RNA be sufficient, it would be possible to measure more genes by RT-PCR or, using a NanoString customized panel combining for example aging-associated genes and the Extended Core Clock Network (ECCN) on nCounter SPRINT profiler or whole genome sequencing via RNA-seq. This analysis will be carried out using saliva samples of participants from the exposure groups as well as their age-matched controls.

Expected outcomes

The success of this study relies on the primary objective, which is the detection of circadian expression profiles from saliva samples of the exposure (AIDM and/or circadian recommendations) and control groups. If the circadian profile can be observed, the study will be considered successful. The secondary objective of this study includes exploring the impact of exposure on circadian rhythms, which might be directly influenced by factors such as age, and menopause stage.

Primary endpoint

Evaluation of the circadian expression profiles of core-clock genes and clock-controlled genes from saliva samples of the study participants in the exposure groups, as well as in the control group.

Secondary endpoints

-

1.

Analysis of the influence of age on the circadian profile of participants

-

2.

Analysis of the influence of menopausal changes on the circadian profile and the quality of life of participants.

-

3.

Analysis of the influence of the nutritional exposure and/or circadian recommendations on the circadian profile of participants undergoing menopause.

Exploratory analysis

We will investigate a possible correlation between clock gene expression, hormonal changes, and epigenetic-associated changes in females. Further, we will investigate a correlation between circadian gene expression alterations and variations in physiological parameters (daily activity measurements, heart rate, sleep) obtained via an activity tracker, and nutritional or intestinal parameters (HEI, RDF questionnaire).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics will be carried out to evaluate the demographic, menopause transition stage, questionnaire data, gene expression data, hormonal, blood test, and epigenetic data. First, the distribution of data will be tested, and based on the outcome, one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test (for parametric distribution) or Kruskal-Wallis test (for non-parametric distribution) will be carried out. Moreover, we will carry out the Welch test to compare the means of measured variables between the exposure and control groups in case of unequal variance for normally distributed data. For all the statistical tests, the significance threshold level will be set to (α) 0.05. In addition, we will perform an ANCOVA to investigate the influence of an exposure on circadian rhythm parameters, taking into account potential confounding factors such as age and menopause stage. By controlling for these covariates, we aim to assess how the nutritional exposure and/or circadian recommendations affects circadian rhythms independent of the participant’s age and menopausal status. This approach will help elucidate the true effects of the exposure groups on circadian patterns.

Gene expression data analysis

The expression levels of each participant’s clock or aging-associated genes, measured by RT-PCR will be analyzed using the ddCT method, which requires normalization to the housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH) followed by the normalization to the mean value across all time points51,52. For the gene expression data measured using the NanoString nCounter platform, the raw count data will be normalized based on positive and negative controls in addition to the housekeeping genes using Nanotube R package53. For the whole genome transcriptomics data measured using RNA-seq, the quality control will be carried out using FastQC54 followed by trimming of the over-represented reads via Trimmomatic55. STAR aligner56 will be used to align the sequencing reads to the reference genome followed by quantification using Salmon57. The data will be normalized using edge R package58.

Assessment of the circadian profile of participants

The temporal expression pattern of each gene is individually tested for circadian rhythmicity either using the Cosinor implementation as in Circular HIerarchical Reconstruction Algorithm (CHIRAL)59 or in Discorhythm60. In this analysis, a cosinor model as shown in (2) will be fitted to the observed values to obtain the amplitude, MESOR, acrophase, R2 (goodness of fit), and p value.

In addition, JTK_CYCLE61 will also be used to infer all types of cycling behavior within the measured genes in the study.

Differential rhythmicity and differential expression analysis

To evaluate the changes at the gene-expression level among participants from the exposure and control groups, we will carry out differential expression analysis comparing the average expression of each gene between the two sub-groups using Limma62. For the set of genes showing different circadian expression patterns in saliva samples from two groups, we will carry out differential rhythmicity analysis using LimoRhyde63 to evaluate the changes in circadian parameters (amplitude, acrophase, MESOR) between both sub-groups. The samples are considered comparable if the difference between the acrophases of a gene in a subject is <4 h and there is no significant diference in terms of amplitude and mesor. The circadian profile of the same clock gene may differ across participants (acrophase ≥ 4 h, and or significant amplitude or mesor differences).

Correlation analysis

To gain a comprehensive understanding of clock-associated changes in both sub-groups and pinpoint the impact of aging and the nutritional exposure and/or circadian recommendations on the circadian phenotype, correlation analysis between molecular, hormonal, activity tracker, questionnaire data, and epigenetic data will be carried out. Depending on the distribution of data (parametric or non-parametric), Pearson or Spearman correlation will be carried out.

Machine learning (ML)

ML methods are valuable for analyzing longitudinal data and help to understand the changes in aging and menopause over time. ML models will be used to uncover complex patterns and interactions between molecular, environmental, and genetic factors influencing aging processes. ML-based algorithms will be used to identify patterns and features associated with menopause and aging, enabling the identification of biomarkers associated with aging in females. Moreover, using ML models we aim to test classification algorithms and features to differentiate the exposure groups and the control group. Both supervised and unsupervised machine learning algorithms will be tested.

Exploring circadian rhythms and aging through multi-dimensional data

CosinorAge64 provides a robust framework for analyzing the diverse datasets collected in our study, including gene expression time courses, cortisol time courses, single time-point melatonin measurements, and smartwatch-derived activity data. Therefore, CosinorAge will be applied to the activity tracker data, as well as other collected datasets such as time course gene expression data, cortisol time courses, and melatonin measurements. This comprehensive approach will allow us to explore the relationship between circadian rhythms and biological aging in our participants, offering critical insights into the interplay between these factors.

Responses