A review of advances & potential of applying nanomaterials for biofilm inhibition

Introduction

Biofilms, characterized as aggregates of microorganisms, are among the most ubiquitous forms of microbial life on Earth1. The proliferation of biofilms raises significant concerns, particularly due to their role in the biological contamination of water systems and the corrosion they cause in pipelines2. Additionally, the presence of harmful microbial strains within these biofilms presents considerable risks to public health and infrastructure. Studies show that parasites and infectious viruses can quickly establish themselves in drinking water biofilms, surviving for periods extending up to a month3. Consequently, the effective control and management of biofilms represent a critical area of concern, demanding innovative and efficient solutions.

Two principal strategies are commonly employed for controlling biofilms: preventing biofilm formation by eradicating potential adherent microorganisms, and reducing microbial attachment using materials that naturally deter adherence4,5,6. The former includes chlorination or ultraviolet (UV) to kill microorganisms. The latter includes control of surface corrosion by advanced materials. The most prevalent approach currently in use is the former, often exemplified by the prevalent application of chlorine in drinking water systems7,8. Although the bactericidal properties of chlorine are well-established, concerns arise with its overuse. Excessive chlorine application leads to the proliferation of chlorine-resistant bacteria within biofilms, increasing the risk of secondary pollution9,10,11. Therefore, there is an urgent need for safe and effective alternatives.

Nanomaterials, defined by their nanoscale dimensions or as composites of nanoscale units, are a promising alternative for advancing biofilm prevention and control. On the one hand, small-scale structures of these materials impart distinctive properties not observed in conventional materials, such as surface effects and size effects12,13 These properties contribute to close contact with microorganisms and even enter the interior of microorganisms, thus achieving more efficient sterilization. On the other hand, the characteristics of some nanomaterials make the surface of their composition not suitable for microbial growth, so to achieve the effect of anti-adhesion14.

Despite the numerous advantages of antibiofilm nanomaterials, their high cost and limited durability due to unsuitable selection of the type and dose of nanomaterials hindered their widespread adoption as replacements for conventional chemical agents. Consequently, the current utilization of nanomaterials in antibiofilm applications remains relatively restricted. Moreover, there is extensive research on the antimicrobial mechanisms for nanomaterials, but insufficient focus is placed on translating these findings into effective antibiofilm applications. Understanding these mechanisms serves as a foundational step towards enhancing and optimizing the performance of nanomaterials against biofilms. Thus, it is urgently necessary to research how to effectively antibiofilm control by nanomaterials based on their anti-adhesion and antimicrobial mechanisms (Tables 1 and 2).

In this review, recent advances in the development of novel nanomaterials for antibiofilm and anti-adhesion were investigated. Anti-adhesion mechanisms rely on the material itself or by physical means to achieve antibiofilm, such as superhydrophobic/superhydrophilicity surfaces. Antimicrobial mechanisms are achieved by chemical stimulation involving chemical reactions, including ions release, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), suppression of the efflux pump, and inhibition of the synthesis of bacterial metabolites. Thus, physical and chemical approaches were discussed to improve antibiofilm performance based on the analysis of the corresponding mechanisms. Commonly used characterization methods in biofilm studies were summarized in two aspects, bactericidal monitoring and anti-adhesion monitoring, which serve as a toolbox for future studies. The specific objectives of this review were to (1) summarize possible means for improving antibiofilm performance, and (2) evaluate antibiofilm performance based on characterization method.

Physical approaches for improving antibiofilm performance

The effect of antibiofilm achieved by the material itself or by physical means usually has the advantage of high controllability. The following types of nanomaterials are reviewed, including mechano-bactericidal surfaces, superhydrophobic surfaces, superhydrophilicity surfaces, acoustic methods, and electrostimulation.

Mechano-bactericidal surfaces

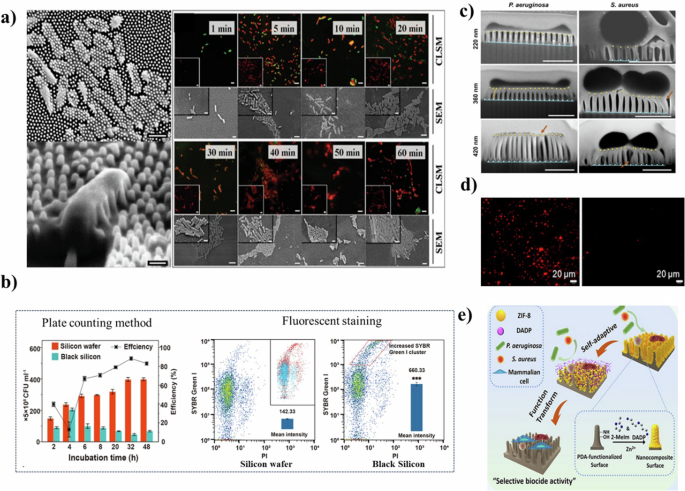

Mechano-bactericidal nanomaterials exert their antimicrobial effects through mechanical forces. This phenomenon was first noted in the bactericidal properties of cicada wing surfaces by Ivanova et al. 15 (Fig. 1a). Subsequent research expanded based on this concept, developing similar bactericidal surfaces16,17. The initial hypothesis posited that bacteria were eliminated by the piercing action of nanopillars15,18. However, recent studies have led to a more comprehensive understanding. It is now understood that bacteria adhere to these nanomaterials, or encounter them, due to gravitational sedimentation12,17. This interaction stretches and compresses the bacterial cell membrane. The goal is to optimize the energy balance by maximizing the contact area between the cell membrane and the nanomaterials12. When the cell membrane cannot withstand the stress from this deformation, it ruptures, leading to bacterial death. Furthermore, Zhao et al.19 found that, even if mechanical damage does not immediately kill bacteria (Fig. 1b), the injured bacteria may produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) in a non-stressful environment, triggering apoptosis. This could be attributed to the accumulation of misfolded proteins or the presence of certain metal elements within the cells20.

a P. aeruginosa cells penetrated by the nanopillar structures on the wing surface (left), and CLSM images and SEM images of P. aeruginosa cells adhering to the surface of the cicada wing. (right)15 Copyright 2012, Wiley-VCH. b The difference between the two tests suggests bacterial damage rather than death19 Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications. c FIB-SEM side profile images of the substrata with nanopillars of different heights exposed to P. aeruginosa and S. aureus cells22 Copyright 2020, PNAS. d The surface with superhydrophobic properties (right) removing dead bacteria residues compared to ordinary surfaces (left)24 Copyright 2020 Elsevier B.V. e Schematic illustration of the synthesis and acting mechanism of the self-adaptive surface28 Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications.

Delivering sufficient mechanical force to bacterial cells remains a significant challenge in the development of mechano-bactericidal surfaces. Crucial to this endeavor is the tuning of geometric parameters like height, density, diameter, and surface regularity, which directly influence interactions with the bacterial cell wall, thereby affecting the bactericidal efficacy. Nanostructures with a height of approximately 200 nm are pivotal for mechano-inactivation. Heights below this threshold allow bacteria to evade cell envelope rupture by creeping to the base21. Conversely, excessively tall structures lead to nanopillar aggregation, diminishing the exerted pressure22 (Fig. 1c).

Bacterial colonization patterns show a preference for depressed areas, with a tendency to maximize surface contact at adhesion points17. Hence, controlling nanostructure density is vital for effective antibacterial activity. Overly dense structures create a “bed of nails” effect22, while sparse densities fail to exert sufficient pressure. Determining the optimal density for various nanomaterials is essential to enhance antibacterial efficiency.

The sharpness of nanopillars also plays a crucial role. Extremely sharp nanopillars induce greater cell deformation, contributing to antibacterial action, but they may compromise mechanical stability as they are prone to snapping21,23. Additionally, surfaces with irregular topographies demonstrate superior antibacterial properties. The bending of protruding, irregular nanopillars under pressure increases stress on bacterial cells. Moreover, bacteria often release extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) to adhere to these nanopillars. The robust adhesion between nanorods and bacterial EPS, coupled with the shear forces, inflicts membrane damage when immobilized bacteria attempt to detach from the unfavorable surface24,25.

One of the primary challenges with mechano-bactericidal materials is maintaining surface cleanliness. Typically, remnants of bacteria punctured by these surfaces accumulate, diminishing their bactericidal effectiveness16. Recent advancements addressed this issue by integrating additional antimicrobial mechanisms, thus facilitating surface self-cleaning. For instance, merging superhydrophobic characteristics with mechano-bactericidal properties significantly reduces bacterial residue compared to conventional surfaces (Fig. 1d). Bacterial coverage on such enhanced surfaces drops nearly to zero after four cycles, whereas it remains at 37% on standard surfaces. This indicates not only prolonged but also heightened antimicrobial efficiency24.

Another innovative approach involves the application of zwitterion expansion to remove residual bacteria. This method entails grafting zwitterionic polymers onto surfaces, which assists in lifting and clearing bacterial remnants26,27. Additionally, adaptive strategies are being explored to counteract microbial growth and propagation. These strategies involve detecting and responding to environmental changes induced by microorganism activity. A notable example is the application of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanoparticles, embedded with the bacteriostatic molecule 3,3′-diaminodipropylamine (DADP), on nanopillar surfaces28 (Fig. 1e). Initially, a pH drop triggered by cell proliferation leads to the degradation of ZIF-8 particles, releasing DADP for rapid bacterial inhibition. Following the depletion of DADP, the refreshed surface continues its bactericidal function through mechanical stress. This dual-action approach effectively addresses the issue of bacterial mass reproduction.

In summary, nanomaterials exhibiting mechano-bactericidal effects are gaining prominence due to their safety and non-toxic nature. Continuous improvements and developments in this field aim to achieve higher antimicrobial efficiency. Future research could focus on enhancing surface self-cleaning capabilities by incorporating novel nanomaterials endowed with multiple antimicrobial mechanisms.

Superhydrophobic surfaces

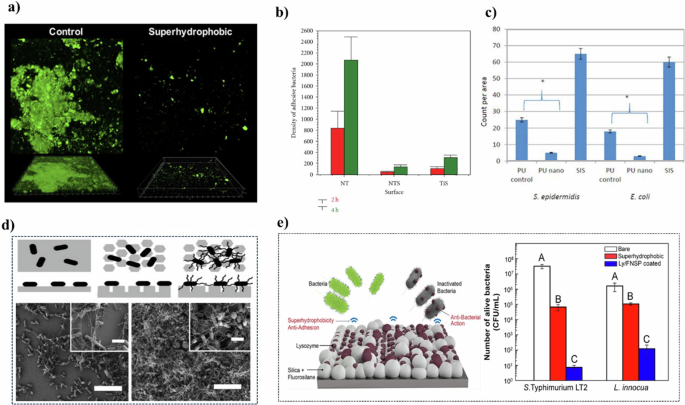

Superhydrophobic surfaces, characterized by their non-wettability, are inherently unsuitable for planktonic bacterial adhesion, thereby hindering biofilm formation. The combined effect of high surface roughness and low surface energy on these surfaces substantially diminishes bacterial contact29,30 (Fig. 2a). This dual characteristic—rough texture and low surface-free energy—thermodynamically discourages bacteria from adhering to superhydrophobic surfaces, effectively reducing biofilm proliferation31,32.

a Confocal images of the polymicrobial biofilm with superhydrophobic (right) and ordinary surfaces (left)35 Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications. b The treated film formed a superhydrophobic surface (NTS) compared with the original film (NT) and hydrophobic film (TiS)34 Copyright 2011, John Wiley & Sons Ltd. c Comparison of cell density among treated PU, control group, and small intestinal submucosa (SIS)37 Copyright 2013, WILEY PERIODICALS. d The schematics (top) and SEM image (bottom) of E. coli adhesion on PDMS surface39. e The mechanism of superhydrophobic surfaces on antibacterial properties42 Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications.

Natural superhydrophobic entities, such as taro leaves, demonstrate resistance to the adhesion of both living bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and abiotic particles (e.g., 4 μm microspheres)33. While in the research of Tang34, the titanium plate was firstly calcined to form anatase phase hydrophilic TiO2 nanotube film. Subsequently, the nanotube films and titanium oxide were treated with perfluorooctane-triethoxysilane (PTES) to form superhydrophobic and hydrophobic surfaces. Observations indicated a significantly reduced microbial population on the superhydrophobic surface compared to traditional TiO2 nanotube films, with bacteria predominantly in a dispersed state (Fig. 2b). In a similar vein, Souza et al.35 developed a superhydrophobic coating on Ti surfaces using low-pressure plasma, which decreased microbial adhesion by about eightfold in two hours compared to pure Ti disks. This surface also exhibited favorable biocompatibility, as evidenced by successful fibroblast cell attachment and proliferation. Notably, the antibacterial efficacy of this coating stemmed from its structure rather than chemical additives, conferring advantages like enhanced durability and reduced risk of promoting drug resistance.

In another study, nanopatterns on thin films were engineered to increase surface roughness, thereby achieving a superhydrophobic effect36. This roughness altered the physical conditions for cell growth and differentiation, eventually leading to an environment that inhibits bacterial adhesion and growth. Yao et al.37 treated the surface of a polyurethane (PU) membrane with HNO3 to induce a superhydrophobic effect (Fig. 2c). The resultant surface exhibited an antibacterial efficiency enhanced by 6 times against Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis) and 8 times against Escherichia coli (E. coli) compared to conventional membranes.

However, the efficacy of superhydrophobic surfaces in repelling bacterial attachment, when compared to conventional surfaces, is somewhat limited. Specifically, these surfaces are more effective at reducing bacterial attachment in non-submerged or dry environments38. In contrast, under fully submerged conditions, the inherent structure of superhydrophobic surfaces, while capable of delaying wetting by trapping air pockets, is not impervious to bacterial infiltration. The flagellar filaments of bacteria can penetrate these air-filled voids, consequently diminishing the surface’s hydrophobicity (Fig. 2d). This penetration not only compromises the surface’s repellent properties but also fosters an environment that is more favorable for biofilm development39.

To augment the antibacterial effects, recent research began exploring the synergy of superhydrophobic surfaces with other antibacterial strategies. For instance, drawing inspiration from the lotus leaf, the self-cleaning property of superhydrophobic surfaces is being utilized to address the issue of dead bacterial accumulation on mechanically sterilized surfaces24. Liu et al.40 demonstrated that the integration of silver nanoparticles with a superhydrophobic surface initially reduces microbial attachment. As the hydrophobicity diminishes over time, the sustained release of silver ions ensures a prolonged and reliable antibacterial effect. Wu et al.41 developed a material by growing silver particles on the surface of poplar wood, followed by a modification with stearic acid. This material exhibited an impressive 99% antibacterial efficiency, primarily due to the superhydrophobic nature of the surface, which minimizes the contact area between the bacterial suspension and the coating. Additionally, the silver ions present on the surface exert a potent oxidative effect on bacterial proteins, lipids, and DNA.

Another noteworthy approach involved creating a coating combining lysozyme with fluorinated silica nanoparticles (Ly/FSNP)42 (Fig. 2e). The construction of a superhydrophobic surface enhances its roughness, leading to an uneven topology that increases the concentration of lysozyme per unit area. This results in a higher local lysozyme dosage compared to that in the bulk solution, thereby intensifying the antibacterial effect.

In general, superhydrophobic surfaces are a kind of nanomaterial based on anti-adhesion. Although the superhydrophobic surface has a relatively poor inhibition effect on the formation of biofilm, as it cannot directly cause bacterial death, and the antibacterial effect is more from the weakening of the initial adhesion of bacteria, the advantage of long-term use, in theory, makes the superhydrophobic surface great potential. By combining with the partially controlled sterilization, the defect of the performance attenuation of the superhydrophobic surface under long-term use is also made up, and the durability of the superhydrophobic surface is further improved.

Superhydrophilicity surfaces

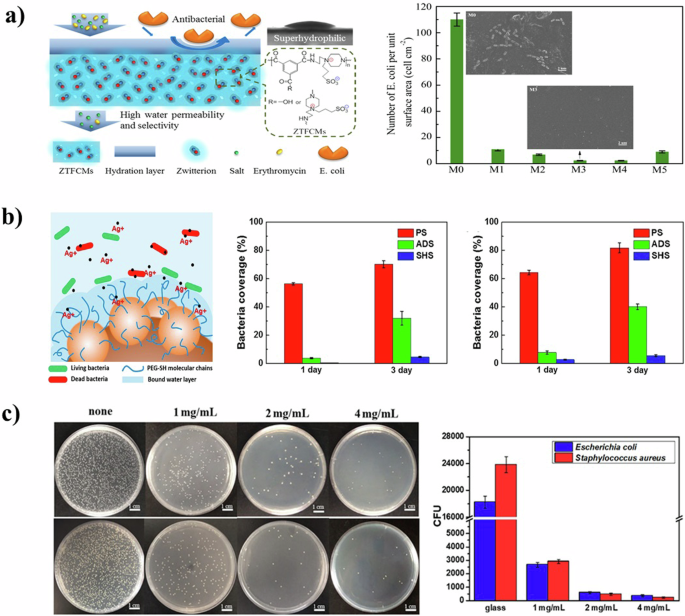

Superhydrophilic surfaces also demonstrate a remarkable ability to repel bacterial colonization. Bacteria are thermodynamically more inclined to remain suspended rather than adhere to superhydrophilic surfaces, making these surfaces resistant to initial colonization and bacterial attachment31,43,44. Weng et al.45 synthesized a zwitterionic polyamide composite nanofiltration membrane (ZTFCMs) characterized by pronounced superhydrophilicity (Fig. 3a). Compared to conventional membranes with lower hydrophilicity, the adhesion of E. coli on ZTFCMs was significantly reduced. This phenomenon is attributed to the formation of a dense water layer on the highly hydrophilic surface of ZTFCMs. The water layer acts as a barrier, preventing direct interaction between the bacteria and the membrane surface and thereby inhibiting biofilm formation.

a Schematic model for water transport and antibacterial illustration of ZTFCMs (left), and umber of E. coli adhered onto the membrane surfaces estimated by SEM images (right)45 Copyright 2016, Elsevier B.V. b The schematic illustration of the antibacterial mechanism under immersed condition (left), and the bacteria coverages of E. coli (middle) and S. aureus (right) on different surfaces52 Copyright 2018, Elsevier B.V. c Antimicrobial test results of the glass slides with different protein coatings, E. coli (upper left) and S. aureus (lower left), and statistic data (right) of E. coli and S. aureus adhesion on different samples55 Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications.

Beyond the capacity to prevent bacterial attachment, superhydrophilic surfaces also exhibit bactericidal effects under specific conditions46. When the liquid present on these surfaces evaporates, mechanical sterilization is enabled through capillary attraction at the gas-liquid interface46. Mechanical analysis revealed that increased Laplacian pressure on relatively more hydrophilic surfaces counters the surface tension, enhancing the total capillary attraction47. Additionally, the extreme hydrophilicity of these surfaces imparts these surfaces with anti-fog and self-cleaning capabilities48,49,50. These properties not only contribute to maintaining surface cleanliness but also enable the surfaces to perform multiple functions simultaneously, including the prevention of microbial attachment.

The self-cleaning property of superhydrophilic surfaces significantly enhances bio inhibition by reducing both bacterial adhesion and the accumulation of dead bacterial residue24,51. Additionally, multilayer antibacterial and antifungal superhydrophilic films were developed for stainless steel surfaces. This involved the deposition of polydopamine (PDA) and silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs), followed by modification with methoxy-polyethylene glycol mercaptan52. The antibacterial efficacy of these films is initially facilitated by the release of silver ions, and subsequently sustained by the superhydrophilic nature of the surface. This dual-strategy approach ensures both rapid, short-term and prolonged antibacterial effects (Fig. 3b).

Prawira et al.53 crafted a self-cleaning TiO2 coating using a dipping method, enhanced by incorporating graphene, Ag, Fe, and other additive materials. While the addition of graphene and Fe exhibited a modest inhibitory effect on E. coli, the antibacterial efficiency increased with higher additive concentrations. In another study, Boinovich et al.54 employed nanosecond laser processing to create surfaces on copper that were alternately superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic. The superhydrophilic copper substrates demonstrated superior antibacterial performance compared to both bare copper and superhydrophobic copper substrates. This enhanced antibacterial action was attributed to the aggregation of copper ions resulting from surface corrosion. Notably, superhydrophilic copper alloys, being more susceptible to corrosion than their superhydrophobic counterparts, exhibited stronger surface antibacterial properties.

The stability issue of the superhydrophilic surface remains to be further explored. As for the combination of metal ions and superhydrophilic surface, how to realize long-term stable use by extending the ion release time needs further study. Qi et al.55 prepared a superhydrophilic surface coating based on mussel-inspired chimeric protein. Zwitterionic peptides are extremely hydrophilic due to electrostatic-induced hydration, which allows water molecules to rapidly expand into a hydrated film. The tightly bound water layer prevents bacteria from interacting with the membrane surface and inhibits biofilm formation. The coating showed a strong effect on E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), as evident by the reduction of adhesion by 98.1% and 99%, respectively (Fig. 3c).

In conclusion, the superhydrophilic surface usually has a better effect on the anti-adhesion of bacteria. However, as superhydrophilic surfaces are more prone to corrosion and destruction54, the stability of superhydrophilic surfaces still needs to be improved. To be applied in more fields, how to manufacture long-term stable superhydrophilic antibacterial surfaces is still a problem to be studied. In addition, binding to superhydrophilic surfaces via ion release is a feasible idea, but the potential risks of ion release should also be considered.

Acoustic methods

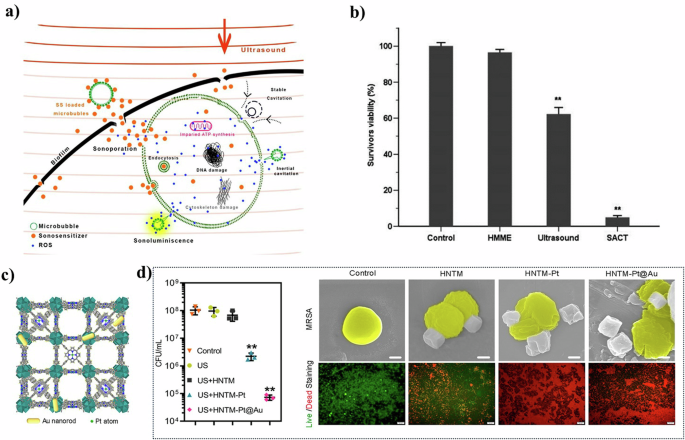

In a seminal study in 1995, Kessel et al. discovered that ultrasound-induced cavitation effect could cause acoustic damage to cells56. Cavitation is the process of bubble formation under the pressure generated by ultrasonic waves. These bubbles undergo expansion and collapse, generating considerable energy57. A portion of this energy is released as light, which, through photochemical reactions, produces reactive oxygen species (ROS). Additionally, free radicals may be generated by the pyrolysis of water molecules58. Beyond chemical effects, the physical collapse of these bubbles also results in mechanical energy, manifesting as microjets and microstreaming, which disrupt cell membranes (Fig. 4a). While ultrasonic radiation alone can induce cavitation, it typically requires substantial energy and suffers from intense attenuation. The efficiency and efficacy of cavitation can be significantly enhanced by the use of sonosensitizers. These agents facilitate cavitation at lower energy levels, thereby reducing overall energy consumption and enhancing the feasibility of continuous operation59 (Fig. 4b).

a Proposed physical and biochemical mechanisms involved in antimicrobial SDT58 Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications. b Bactericidal effect of HMME-mediated SACT (SACT) on S. aureus59 Copyright 2014, Federation of European Microbiological Societies. c View of the 3D structure of HNTM-Pt@Au and d in vitro antibacterial performance and MC3T3-E1 cytotoxicity70 Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications.

Sonosensitizers are typically categorized into two groups: organic molecules and inorganic nanomaterials60. Organic small molecules, such as porphyrins, porphyrin analogs56, and rose Bengal61, are traditional sonosensitizers. Despite their acoustochemical effectiveness, many of these organic molecules suffer from low stability, which limits their practical application. These sonosensitizers are inherently hydrophobic and tend to aggregate in aqueous environments62. A practical solution to this challenge involves encapsulating or aggregating these small organic molecules within nanoparticles. This approach enhances their stability and allows for targeted release at specific locations61. For instance, emodin was successfully encapsulated in lipids to create nano-emodin, which facilitates slow release, thereby prolonging its action time63. Additionally, fabricating organic small molecules through self-assembly is another strategy to improve their stability and biological adaptability. However, the issue of biological toxicity associated with small organic molecules remains a significant concern. Therefore, when developing organic subclasses of sonosensitizers, it is crucial to consider the trade-off between biosafety and stability.

Inorganic nanomaterials are increasingly favored over organic small molecules as sonosensitizers due to their controllable morphology, ease of surface functionalization, and higher stability64,65,66. However, a common limitation of traditional inorganic nanomaterials is their relatively unsatisfactory ultrasonic absorption coefficient, resulting in poor ROS yield60,67. To address this, researchers focused on improving the structure of nanomaterials to enhance ultrasonic efficiency. A notable example is the development of Janus nanoparticles (NPs), created by modifying porous silicon with the nanostopper technology68. These nanoparticles feature a hydrophobic inner surface and a hydrophilic outer surface, which effectively promotes microbubble growth and thus increases ROS production efficiency65. Another promising approach involves the incorporation of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). MOFs overcome the limitations of inadequate absorption performance due to their adjustable physicochemical properties67,69. For example, Yu et al.70 developed a multifunctional, ultrasound-responsive material named RBC-HNTM-Pt@Au. This material comprised a gold nanorod (NRs)-actuated single-atom-doped porphyrin metal−organic framework (HNTM-Pt@Au) and a red blood cell membrane (RBC) coating (Fig. 4c). The innovative design not only enhances acoustic catalytic activity but also improves the absorption of ultrasonic energy. As a result, the antibacterial efficiency against MRSA reached 99.9% under 15 min of ultrasound irradiation (Fig. 4d).

The efficacy of acoustically induced disinfection is significantly influenced by the strength of the ultrasound, alongside the choice of sonosensitizer. Theoretically, stronger ultrasound generates a more intense cavitation effect, leading to greater bactericidal efficiency. However, excessively powerful ultrasound results in energy wastage and potential harm to human health. Due to an incomplete understanding of the acoustic stimulation mechanism, optimizing energy use remains a formidable challenge71. Furthermore, accurately quantifying ultrasonic energy is difficult since the control and measurement of sound field parameters are reliant on the output capabilities of the sound field device, hindering precise readings of the actual sound field energy. Another critical aspect in acoustically stimulated antibacterial applications is oxygen supplementation6. The continuous operation and ROS generation can deplete oxygen levels, potentially causing environmental hypoxia. Recent advancements include the integration of inorganic nanozymes to regulate this issue. An example of this is the use of Pd@Pt nanoplates, which exhibit catalase-like activity, facilitating the decomposition of H2O2 into O272. When these nanoplates are modified with the organic sonosensitizer meso-tetra(4-carboxyphenyl) porphine (T790), their catalase-like activity is initially inhibited but can be reactivated under ultrasound irradiation. This ultrasound-switchable enzyme activity enables a dual function: effective ultrasonic antibacterial action and oxygen supplementation, without compromising safety.

In summary, the antibacterial effect induced by ultrasound is further improved after the introduction of nanomaterials, and the research on antibacterial performance in the medical field is quite sufficient. The ability of acoustic induction to achieve site-specific pair removal also gives it a unique advantage in the face of biofilm contamination. However, the use of energy is still one of the current dilemmas. If the input sound energy can be directly related to the removal efficiency, the energy waste and possible hidden dangers caused by excessive sound energy input can be reduced while ensuring the removal efficiency.

Electrostimulation

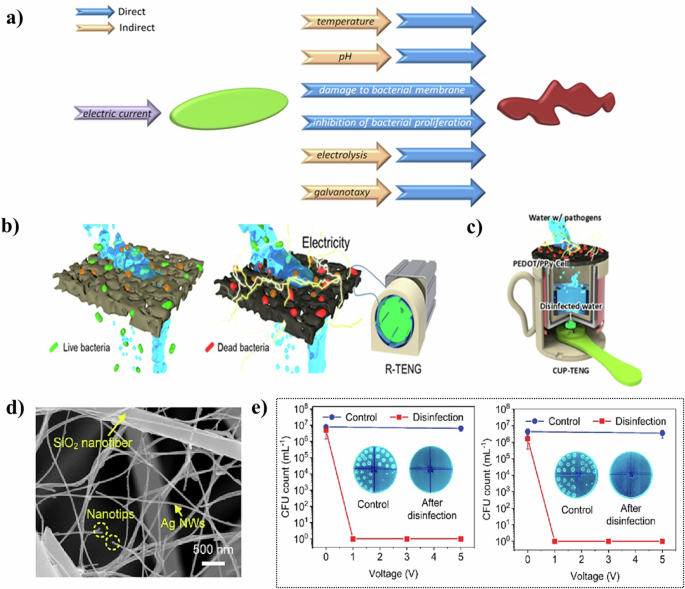

The antibacterial effect of electrostimulation is categorized into direct and indirect mechanisms73 (Fig. 5a). The direct mechanism involves cell damage through electroporation74, a process where electrical fields create pores on cell membranes, or by disrupting electron transfer processes essential for bacterial respiration and proliferation75,76. Indirect mechanisms, on the other hand, encompass the generation of changes in ambient pH through electrolysis and the production of antibacterial agents77. These indirect processes modify the environmental conditions, thereby inhibiting bacterial growth and survival.

a Direct and indirect mechanisms of inhibition of bacterial growth under the influence of electric current74 Copyright 2019, Elsevier B.V. b Illustration of the entire process in the electroporation-assisted POU water sterilization system and c Schematic illustration of the operation mechanism of the CUP-TENG equipped with the PEDOT/PPy-Cell membrane79 Copyright 2021, Elsevier Ltd. d The microscopic architecture of NNAs and e biocidal activity against E. coli (left), S. aureus (right)78 Copyright 2023, Elsevier B.V.

Regarding direct mechanisms of electrostimulation for antibacterial effects, Yu et al.78 developed biomimetic nanofiber aerogels by assembling Ag nanowires within a 3D SiO2 nanofiber skeleton using a freeze-drying method (Fig. 5d). These aerogels, characterized by their super elasticity and conductive network, absorbed negatively charged microbes through conducting nanonets composed of Ag nanowires. They effectively neutralized viruses and bacteria via the “point discharge” effect at the nanotips. Remarkably, these aerogels demonstrated a disinfection efficiency of 99.9999% against E. coli at a mere 1 V, with the concentration of Ag+ released remaining below detectable levels (<0.01 mg/L) (Fig. 5e). The energy consumption was only 0.83 Wh/m3, highlighting their potential as efficient and eco-friendly materials for water treatment.

Cho et al.79 designed a triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) integrated with conductive cellulose membrane filters for microbial inactivation driven by triboelectricity (Fig. 5b). The electricity generated by the TENG disrupted the microbial cell membranes trapped on the membrane surface, leading to rapid inactivation through two-way leakage at high output voltages. After three filtration cycles, this setup achieved a 100% microbial removal efficiency against E. coli and S. aureus. The team also developed a manual CUP-TENG powered by hand movement, making it a compact, portable, and independent solution suitable for water purification in extreme conditions, like disaster relief and power shortages (Fig. 5c).

In addition to electroporation, altering the bacterial membrane potential serves as another direct antibacterial mechanism. External electrical stimulation can modify ion flux across the membrane, potentially influencing gene expression80. Zamora-Ledezma et al.81 fabricated graphite nanoplatelets/poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) composite films via drop casting. After a 12-h treatment at a 15 MHz current frequency, the cell survival rate of E. coli was reduced to about 27%. This external stimulation disrupted electrical signaling within biofilms, thereby affecting cellular metabolism and proliferation75,82 Notably, the required current was minimal (I < 0.6 mA), suggesting its safety for biological applications and broad research potential.

In terms of indirect mechanisms, the application of nanomaterials in the electrolytic production of antibacterial agents expands the scope of antibacterial applications. Kumar et al.83 developed a carbon foam coated with reduced graphene oxide–silver nanostructures. Upon applying a voltage of 1.5 V, ROS production was significantly enhanced. It is hypothesized that the electric field effect under the applied voltage synergistically worked with ROS production to amplify the bactericidal effect. Impressively, this material achieved complete bacterial elimination within 5 min over 10 cycles, demonstrating both low power consumption and rapid purification capabilities. Cao et al.84 enhanced the surface of Co3O4 nanoneedles with MnOOH nanoparticles through a hydrothermal treatment process, creating a MnOOH-coated Co3O4 nanoneedle (MCO) composite. The MnOOH nanoparticles augmented the charge storage capacity of the Co3O4 nanoneedles, and the reduced adsorption of OH– ions led to an increase in the production of extracellular ROS. This enhancement effectively compensated for the limited active sites on Co3O4 and the restricted ROS production. Charged at 1.4 V for 30 min, the MCO composite demonstrated an impressive 99.999% removal efficiency against various bacteria within just 5 min.

Electrostimulation, when synergized with other technologies, significantly boosts antimicrobial effectiveness. For instance, while a standalone Ag-CNT/ceramic membrane may struggle to sustain long-term antibacterial and antifouling effects due to rapid Ag+ release, coupling it with an electric field markedly enhances its efficacy85 This improvement is primarily attributed to the electrostatic repulsion created by the electric field and the ROS generated by the catalysis of silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs)86. Additionally, the electric potential helps to inhibit the dissolution of Ag NPs, thereby extending the lifespan of the membrane. After 12 h of filtration with an active electric field, the size of the Ag NPs remained relatively unchanged. In contrast, without the electric field, the Ag NP size reduced from an average of 9.2 ± 3.0 nm to 7.5 ± 1.4 nm. This observation underscores a common challenge with metal nanomaterials: the issue of ion release. However, controlling this release through electric potential not only mitigates this issue but also concurrently strengthens the antibacterial effect.

Electrostimulation is a direct and highly effective antibiofilm method with excellent microorganism removal effects. Additionally, it also controls the release of ions to prolong service life as an auxiliary method. Currently, more emphasis is placed on achieving rapid sterilization effects. The ability to achieve normalized sterilization effects with lower electrical energy or use electrical stimulation as an emergency treatment after conventional antibacterial methods fail will broaden the potential applications of this approach.

Chemical approaches for improving antibiofilm performance

In contrast to physical stimulation, chemical stimulation refers to a class of nanotechnology in which a material is antibacterial either by itself or by initiating a chemical reaction, including Ions Release, Generation of ROS, Suppress the efflux pump, and inhibit the synthesis of bacterial metabolites. Among these mechanisms, Ions Release and Suppress the efflux pump can be considered direct approaches, as they exert antibacterial effects through the inherent properties of the materials. Conversely, Generation of ROS and Inhibit the synthesis of bacterial metabolites are classified as indirect approaches, since they achieve antibacterial effects by producing or regulating chemical compounds.

Ions release

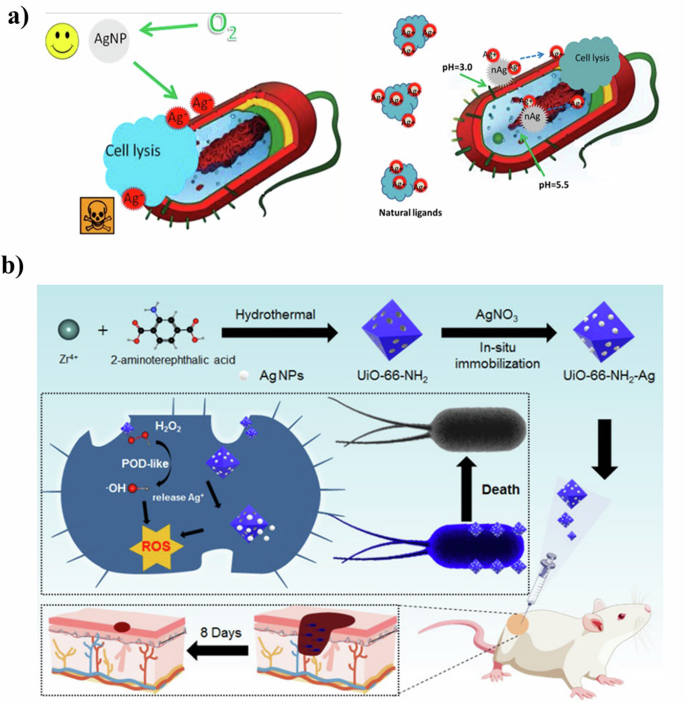

Metal-based nanomaterials exert antibacterial effects primarily through the release of positively charged metal ions. These metal ions, attracted to the negatively charged bacterial membrane via Coulombic attraction, exhibit a high affinity for the sulfhydryl groups in proteins. Once inside the cell, these ions deactivate intracellular enzymes and proteins, leading to bacterial death due to impaired proliferation (Fig. 6a). A range of metal ions, including silver (Ag+), zinc (Zn2+), iron (Fe2/3+), manganese (Mn2+), lead (Pb2+), cobalt (Co2+), cadmium (Cd2+), and mercury (Hg2+), are known for their antibacterial properties with different dosage thresholds87,88,89,90,91. There are also many nanomaterials that achieve biofilm resistance through ion release. For example, Xiu et al.92 highlighted that the primary toxicant in silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) is Ag+. They found that under anaerobic conditions, which precluded Ag(0) oxidation and Ag+ release, Ag NPs did not exhibit toxicity. This suggests that antibacterial activity is modulated by controlling Ag+ release, potentially through adjusting factors like oxygen availability, particle size, shape, and coating. HKUST-1 (Cu3(BTC)2, H3BTC = 1,3,5,-benzenetricarboxylate) is a classic example of a copper-based (MOF). Zhang et al.93 demonstrated HKUST-1’s potent antifungal activity against common yeasts and molds found in food processing industries. The antibacterial mechanism of HKUST-1 is attributed to its ability to release Cu ions from its structure. This release occurs as the MOF slowly degrades, producing extra-framework surface Cu(I) due to the cleavage of Cu−O bonds and structural collapse when exposed to water molecules94.

a Ag NPs can release silver ions in an aerobic environment to achieve bactericidal effects (left), and can be used as a carrier to more efficiently transport Ag+ to the cytoplasm and membrane92 Copyright 2012, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications. b Schematic illustrations of the synthesis process of well-dispersed Ag NPs anchored with porous MOF-based UiO-66-NH2 to form UiO-66-NH2-Ag nanocomposite and their peroxidase-like activity synergistic Ag+ release for high efficient and rapid bacterial elimination96 Copyright 2022, MDPI.

While metal ions are known for their potent antibacterial properties, they often exhibit considerable human toxicity. To amplify the antibacterial effects while minimizing self-toxicity, researchers turned to the doping or surface functionalizing of metal-based nanomaterials95. Zhou et al.96 developed a porous MOF-based Ag nanocomposite using an in-situ immobilization synthesis strategy. In this method, Ag NPs were anchored onto Zr-2-amino-1,4-benzenedicarboxylate, a Zr-based MOF known for its low toxicity, thermal, and chemical stability, making it an ideal carrier for Ag NPs (Fig. 6b). This nanocomposite not only reduced the required dosage of Ag NPs, but also significantly enhanced biosafety. At a concentration of 12 µg/mL, it effectively inactivated ampicillin-resistant E. coli and Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis). Kumar et al.97 reported the creation of gallium (Ga) doped carbon dots (Ga@C-dots) exhibiting antimicrobial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa). These Ga@C-dots were synthesized by sonicating molten Ga in polyethylene glycol-400, serving both as a medium and carbon source. The incorporated Ga3+ ions disrupt the iron metabolism of P. aeruginosa, enhancing its antibacterial activity. Compared to undoped C-dots, Ga@C-dots showed significantly improved antibacterial properties and remained stable for at least two months post-synthesis.

Liu et al.98 synthesized a series of stable five-membered ring complexes by coordinating Catechin with rare earth elements such as lanthanum (La), gadolinium (Gd), and ytterbium (Yb). These complex nanoparticles were then fixed onto polyamide surfaces using glutaraldehyde as a crosslinker, resulting in rare earth Catechin complex coatings. The coatings, characterized by a reddish-brown hue, exhibited a uniform distribution of nanoparticles on the polyamide surface. When tested against P. aeruginosa using the colony counting method, the coatings significantly enhanced the antibacterial activity of the polyamide membrane. This enhancement was attributed to Catechin’s high cell affinity, which facilitates the transfer of rare earth ions to bacterial surfaces, and Catechin’s inherent ability to inhibit biofilm formation.

Ion release, as one of the more common antibacterial schemes of nanomaterials, is widely studied. At present, a large number of such nanomaterials proved that they have a strong killing effect on microorganisms. While it has the advantage of highly efficient killing of microorganisms, the ion release also has the problem of poor sustained antibacterial effect due to the instability of ions, and the strong bactericidal characteristics also make it a potential threat to the environment99. Based on what is mentioned above, how to control the killing range, strengthen the targeted killing ability, and extend the effective time of this kind of nanomaterials is the research direction worth exploring.

Generation of ROS

ROS are potent oxidizing agents, including superoxide anions (O2–), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (·OH), produced during cellular metabolism. The complex surface electrical properties of nanomaterials can catalyze ROS generation. By adjusting the particle size, shape, and surface modifications, the use of nanomaterials precisely controls the rate and type of ROS generated, making it adaptable to diverse application needs. Metal oxides and semiconductor nanocrystals inherently produce ROS, and do so more efficiently when combined with light or other external stimuli100. This results in nanomaterials having more efficient, controllable, and customizable ROS generation capabilities than ordinary materials. (Fig. 7a).

a Flow chart of E.coli changes in ROS generation influenced by nanomaterials103 Copyright 2014, Elsevier B.V. b Schematic illustration of the strategy used to fabricate the enzyme-Ag-polymer nanocomposites and their bactericidal action117 Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications.

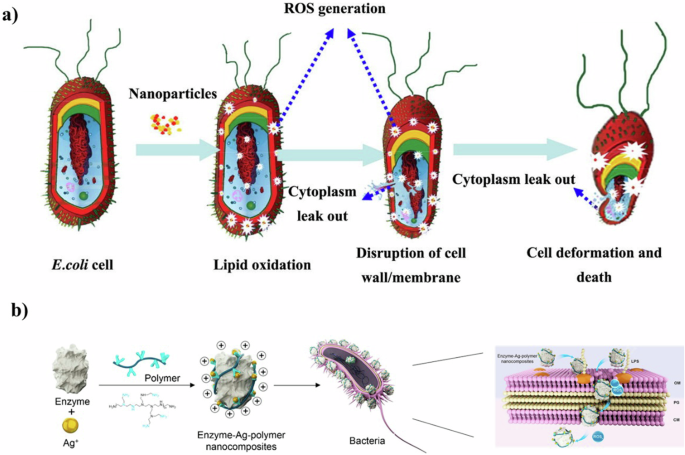

ROS disrupt cellular antioxidant defense mechanisms and react with genetic materials, enzymes, proteins, and other cellular components, causing oxidative damage in bacteria. For instance, silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) induce oxidative stress through ROS production and exhibit strong antibacterial activity against a range of bacteria, including multidrug-resistant strains101. ROS also attacks cell membrane components, leading to lipid peroxidation, bacterial damage, and death102,103,104,105,106. This mechanism is demonstrated by Li et al. using copper titanium alloy against Gram-positive S. aureus, where they found that free radicals caused lipid peroxidation, reducing membrane integrity and fluidity, ultimately leading to membrane destruction107.

Furthermore, ROS degrades biofilm components through peroxidation, thereby dismantling the biofilm structure and impairing its function. Gao et al.108 highlighted the potential of ferromagnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4, MNPs) with peroxidase-like activity to enhance the effectiveness of H2O2 in biofilm degradation. The inherent peroxidase-like activity of MNPs facilitated the enhanced cleavage of nucleic acids, proteins, and polysaccharides in biofilms. Consequently, ROS plays a critical role in inhibiting bacterial growth, and substantial research efforts are being directed toward developing efficient ROS-producing antibacterial nanomaterials. These include metal oxide nanoparticles (e.g., iron oxide, zinc oxide, titanium dioxide), 2D nanomaterials (e.g., graphene-based, metal carbide, and nitride compounds), metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and peroxidase-like nanoenzymes109,110,111.

While ROS are potent agents in causing damage to bacterial cells, they are hindered by limitations such as a short lifespan and limited diffusion distance112,113. The utilization of engineered nanomaterials amplifies ROS production and mitigates these issues. Surface modification techniques are employed to enhance the antibacterial effects of such nanomaterials. Kong et al.114 enhanced the antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles by doping with 2.5% manganese (II) oxide. This modification led to increased ROS generation, resulting in over 60% inhibition loss in both S. aureus and E. coli compared to pure ZnO nanoparticles. Fan et al.115 developed a nickel-cobalt bimetal-doped nanohook-equipped bionanocatalyst, demonstrating a robust capacity for generating ROS under physiological H2O2 levels (50–100 μM). The unique structure of this bionanocatalyst allows it to attach spontaneously to bacteria and their biofilms, localizing its catalytic bactericidal effects to the affected area. Remarkably, this approach achieved a reduction of bacteria by over 99.99%, and treated mature biofilms showed no signs of recurrence.

Combining ROS generation with other antibacterial strategies is a prevalent approach to amplifying antibacterial effects. Qiao et al.116 developed a composite cupriferous hollow nanoshell, comprising a hollow gold-silver (Au-Ag) core and a Cu2O shell. Such nanomaterial not only generates heat and ROS but also releases copper and silver ions, significantly boosting bacterial inhibition efficiency. The study demonstrated that AuAgCu2O nanoshells effectively eradicated extended-spectrum β-lactamase-positive E. coli and methicillin-resistant S. aureus at concentrations below 26.4 μg/mL, particularly when combined with laser irradiation. Xiong et al.117 designed novel lysozyme-Ag-polymer nanocomposites (Fig. 7b). These nanocomposites interact closely with bacterial cells, where the lysozyme component hydrolyzes cell walls, thereby enhancing the penetration of silver ions into the bacteria. Subsequently, the ROS generated by the silver ions act to kill the bacteria. The results of their study revealed that this enzyme-Ag-polymer nanocomposite maintained stable antimicrobial performance, showing 100% inhibition against E. coli and S. aureus, even after six months of incubation at 4 °C.

Overall, although ROS has the disadvantages of a short lifespan and short diffusion distance, its antibacterial effect can be increased by surface modification and combination with other antibacterial methods100,118. At present, ROS shows strong practical application prospects in many fields, such as sewage treatment119, medical field120, and inhibition of biofilm formation121,122. To further enhance the antibacterial effect of ROS, the detailed interactions between ROS and bacterial organisms and the specific effects of different species of ROS on bacterial organisms need to be studied in detail.

Suppress the efflux pump

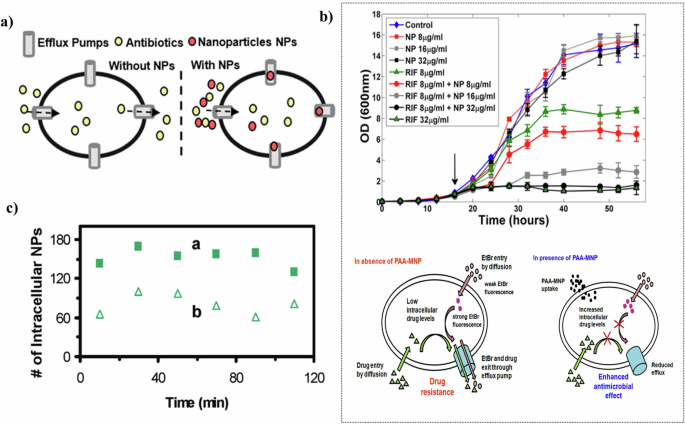

Efflux pumps, crucial membrane-bound transporters found in bacterial cell membranes, play a pivotal role in expelling molecules or ions from cells into the external environment123. In bacterial cells, five major families of efflux transporters are identified: the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS), Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion (MATE) family, Resistance Nodulation cell Division (RND) family, Small Multidrug Resistance (SMR) protein family, and ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) membrane transport system124. These efflux pumps either specialize in transporting a specific substrate or a range of antimicrobial agents with varying structures. Consequently, inhibiting efflux pumps effectively contributes to antibacterial activity.

Nanomaterials emerge as promising agents to suppress efflux pumps. Their high specific surface area and reactivity make nanomaterials particularly suitable for inhibiting efflux pumps, thereby maintaining the reproductive rate of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms at a low level. The unique characteristics of nanomaterials allow for a targeted approach to modulate bacterial resistance mechanisms, offering a potential avenue for enhancing antibacterial strategies. (Fig. 8a).

a Illustration of suppression efflux pump134 Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications. b Enhancement of rifampicin efficacy by PAA-MNP on the growth inhibition of M. smegmatis (above), and schematic showing the probable mechanism of action of PAA-MNP in enhancing the anti-TB drug efficacy (below)126 Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications. c The amount of Ag NPs in P. aeruginosa doubled after the addition of proton ionocarriers (proton dynamic inhibitors) (a) compared to that without the addition (b)130 Copyright 2010, American Chemical Society. Reprinted with the kind permission from ACS Publications.

The efficacy of nanoparticles in suppressing efflux pumps is substantiated through various studies. Banoee et al.125 demonstrated that zinc oxide nanoparticles inhibited the NorA efflux pump in S. aureus. Their research indicated a notable increase in the suppression zone for ciprofloxacin—27% for S. aureus and 22% for E. coli—in the presence of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Afterward, Padwal et al.126 investigated the use of polyacrylic acid-coated iron oxide (magnetite) nanoparticles (PAA-MNP) in combination with rifampicin against Mycolicibacterium smegmatis (M. smegmatis) (Fig. 8b). They highlighted the efflux inhibitory role of PAA-MNP, noting that its addition resulted in a fourfold increase in growth inhibition. These studies underscore the potential of nanoparticles not only as direct antibacterial agents but also as adjuvants that enhance the effectiveness of existing antibiotics by targeting bacterial resistance mechanisms.

Nanoparticles are thought to suppress efflux pumps in bacteria through two primary mechanisms. The first involves nanoparticles directly binding to the active sites of efflux pumps, thereby acting as competitive inhibitors. This binding prevents the expulsion of antibiotics from the cell. Christena et al.127 demonstrated this phenomenon with copper nanoparticles, which inhibited the NorA efflux pump, partly through the generation of Cu(II) ions. This direct effect of copper nanoparticles suggests an interaction between the nanoparticles and the efflux pumps. The second mechanism by which nanoparticles may disrupt efflux pumps involves altering efflux dynamics. Studies on the impact of silver nanoparticles on the MDR efflux pump MexAM-OPrM in P. aeruginosa suggest that these nanoparticles disrupt membrane potential or proton motive force. This disruption reduces the driving force necessary for efflux128,129. Chatterjee et al.102 observed a significant decrease in the membrane potential of E. coli cells, from −185 mV to −105 mV and −75 mV, after exposure to copper nanoparticles at concentrations of 3.0 and 7.5 μg/mL for 1 h, respectively. These findings indicate that nanoparticles not only inhibit efflux pumps directly but also affect the overall cellular dynamics necessary for the functioning of these pumps.

The utilization of nanomaterials to inhibit efflux pumps offers dual benefits: it not only impedes the expulsion of antibiotics, thereby augmenting the effectiveness of conventional antibiotics but also obstructs the efflux of quorum-sensing biomolecules, consequently diminishing the biofilm-forming capabilities of bacterial cells130. Ahmed et al.131 demonstrated this with chlorhexidine-coated gold nanoparticles, which effectively suppressed bacterial adhesion, colonization, and the release of EPS. This nanomaterial not only inhibited the biofilm formation of K. pneumoniae, but also eradicated preformed biofilms. Vieira et al.132 developed a chlorhexidine (CHX)-carrier nanosystem using iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles (IONPs) combined with chitosan (CS). The IONPs-CS-CHX nanosystem was shown to effectively reduce both the formation of biofilms and the viability of preformed biofilms of Canidia Albicans (C. albicans) and Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) in both single and mixed cultures. The integration of metal nanoparticles with conventional antibiotics133,134 presents a promising strategy. This approach not only promises cost and time savings but also potentially reduces the cytotoxic effects of nanoparticles on human cell lines. Targeting efflux pumps and reducing quorum-sensing signals to suppress biofilm formation represents an innovative and multifaceted approach to antimicrobial strategies.

In summary, suppressing efflux pump, as one of the methods to target microbial resistance, inhibits the formation of biofilm as well as the efflux of quorum-sensing biomolecules. However, this method is difficult to achieve direct killing of biofilms, and the application cost of this method is not suitable for large-scale delivery. At present, the main application is still in the medical field with antibiotics. But as a targeted removal method for already formed biofilm environments, this method has great potential.

Inhibit the synthesis of bacterial metabolites

Nanomaterials exert antibacterial effects by inhibiting the synthesis of essential metabolites and disrupting nutrient processing crucial for bacterial growth. For instance, phosphates, vital for gene and protein synthesis in bacteria, are effectively removed by lanthanum-doped polyacrylonitrile nanofibers. These nanofibers facilitate the in-situ formation of aeolotropic and well-dispersed La(OH)3 nanostructures, leading to enhanced phosphate removal due to increased active sites for phosphate binding135 This approach, which prevents lanthanum leakage and maximizes nutrient removal efficiency, holds significant potential for antibacterial applications and water stability.

Beyond nutrient blocking, nanomaterials also inhibit gene replication and protein activity. Researchers observed that silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) hinder bacterial growth and reproduction by condensing DNA, thereby impairing its replication capability and causing degradation. Ag NPs penetrate bacterial cells by creating small openings in the cell wall, leading to membrane damage and intracellular material loss. Furthermore, gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) were shown to bind to ribosomes, inhibiting tRNA synthesis and ATP formation, thereby exerting effective bacterial-killing activity136,137

Additionally, the shape of nanomaterials plays a critical role in their antibacterial efficacy. For example, zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) with conical shapes exhibit a stronger inhibition of β-galactosidase (GAL) activity—an enzyme crucial for metabolizing carbohydrate energy in microorganisms—compared to nanosheets and nanospheres. This enhanced inhibition is attributed to the geometric compatibility of conical ZnO NPs with enzyme active sites, leading to heightened antibacterial activity138.

Research/monitoring methods

Bactericidal monitoring methods

The antimicrobial efficacy of nanomaterials can be quantified using several methods. Plate counting, measured in colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL), is a traditional technique for determining the number of viable and non-viable cells (Fig. 9a). Its widespread use is attributed to the minimal requirement for advanced equipment and highly specialized operators, making it a universally accepted method in most laboratories. However, this method is time-intensive due to the necessity of cell cultivation, and results from single measurements may suffer from experimental bias139. Consequently, it is often used in conjunction with other methods to provide a more comprehensive evaluation.

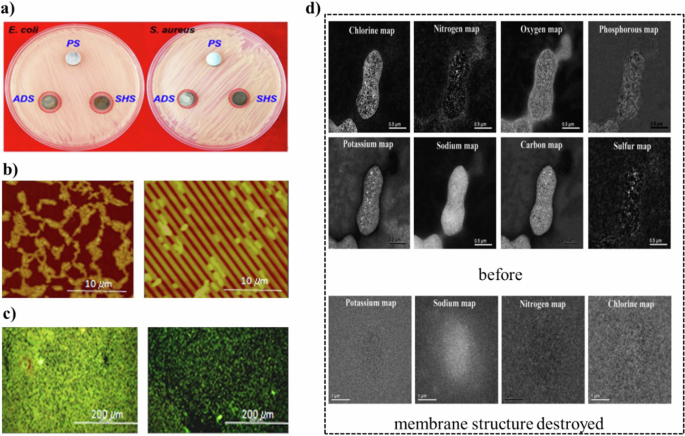

a Inhibition zone test of three surfaces, by comparing the areas of inhibition zones, the range of antimicrobial activity and possible ion release can be analyzed52. b AFM images and c Epifluorescence microscopy images to show the attachment of P. fluorescens144 Copyright 2012, International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. d The EELS elemental mapping analyses before and after the membrane structure destroyed141. Copyright 2020, WILEY-VCH.

Another cultivation-based approach is the inhibition zone test, which demonstrates the antibacterial properties of different materials. This method involves placing nanomaterial-loaded samples on the surface of a uniformly inoculated petri dish with the microorganisms under study. The diameter of the inhibition zone is observed and compared after a period of culture52. This test provides an intuitive comparison of the antibacterial activity of various materials and the release of potential antibacterial agents.

Microscopic observation following fluorescence staining is another prevalent method for assessing antimicrobial efficacy. The use of live/dead staining with SYTO 9 and Propidium Iodide (PI) is particularly favored due to its enhanced contrast in displaying bactericidal effects, hence its wide adoption21,78. An alternative approach involves the genetic engineering of bacteria to incorporate foreign DNA, enabling them to produce fluorescent gene products. For instance, Vailei et al.46 utilized this technique to study the impact of surface wettability on bactericidal performance. Traditional staining methods may inadvertently cause additional bacterial death due to prolonged dye exposure during evaporation. In contrast, green fluorescent protein (GFP) labeling allows for the survival of bacteria under normal conditions. Within this framework, GFP leakage from dead bacteria results in a loss of fluorescence signal, facilitating continuous observation over extended periods.

The aforementioned methods represent common quantitative approaches used to characterize bactericidal effects. In addition to these, qualitative methods are also employed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of bacterial killing. For instance, a widely used method involves using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to depict the cellular morphology17,19,22. These techniques allow for detailed visualization of the surface and internal structure of microorganisms at the nanoscale, facilitating comparisons before and after treatment140. While microscopic methods offer an intuitive display of cell and biofilm morphology, it is important to interpret these images with caution. The observed damage might result from sample preparation processes, or from the interaction between the nanomaterial and the sample during preparation. Hence, SEM and TEM are typically regarded as supplementary tools that aid in elucidating the mechanisms of action.

Flow cytometry, a sophisticated analytical technique, leverages light scattering and fluorescence principles for detailed cell characterization. It offers a rapid, sensitive, and often more comprehensive assessment of microbial populations, including viable but non-culturable (VBNC) organisms. For example, Zhao et al.19 employed this method to discern the impacts of mechanical sterilization on bacterial cells. By comparing the results of plate counting with flow cytometry, they concluded that the cells were inhibited in growth rather than killed. Further analysis using flow cytometry to track intracellular ROS and apoptosis-like death (ALD) markers revealed the prolonged physiological effects of mechanical sterilization on bacteria.

Additionally, electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) is instrumental in detecting changes in the chemical composition and electronic structure of cell membranes, thereby aiding in the identification of inhibition mechanisms. Zhuang et al. found that the complete destruction of the cell membrane was proved by the distribution of various elements before and after the destruction of the cell membrane.141 Utilized EELS to demonstrate the complete destruction of the cell membrane by comparing the distribution of various elements before and after the damage (Fig. 9d). This technique also enables the assessment of the extent of cell membrane damage by analyzing the distribution, size, and polarity of ions inside and outside the cell, thus providing insights into the bactericidal mechanisms.

Monitoring the presence of toxic substances and their impact on cells is a viable method for assessing the bactericidal efficacy of nanomaterials and shedding light on the underlying mechanisms. For instance, the concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated through catalysis or associated chemical reactions can serve as an indicator of bactericidal potency19. Additionally, the level of glutathione (GSH) is often used as a marker to gauge the oxidative capacity, indirectly reflecting the antimicrobial variances among different nanomaterials in oxidative processes142. However, it’s important to note that such methods do not directly demonstrate antibacterial effects. Therefore, they are typically employed as supplementary experiments to compare the performance of similar materials.

In-depth studies of mechanisms in certain fields lead to a comprehensive exploration of factors that influence the bactericidal properties of nanomaterials. For instance, in the realm of mechanical sterilization, primary factors like the height, aspect ratio, and sharpness of nanomaterials are found to significantly impact their bactericidal effectiveness25,143. Consequently, this understanding enables a degree of predictability in their antibacterial action. As research progresses and more samples are analyzed, it becomes increasingly plausible to express bactericidal effects through more direct methods, such as leveraging the inherent characteristics of nanomaterials. This approach could simplify research processes and allow for the representation of bactericidal effects using readily obtainable material property data, making these materials more practical and suitable for real-world applications. Hence, the continued exploration and understanding of these mechanisms are of paramount importance.

The bactericidal effect was speculated and analyzed based on microorganism observation. There is a comprehensive research process for evaluating nanomaterial properties with respect to bactericidal effects. Currently, most research methods focus on testing and analyzing results from a single strain, with less emphasis on studying the impact of complex environments and the removal of biofilms.

Anti-adhesion monitoring methods

The anti-adhesion property of surfaces, distinct from direct bactericidal effects, focuses on reducing bacterial adherence rather than killing the bacteria. Consequently, the methods used to characterize materials with anti-adhesion properties differ. A fundamental approach involves detaching bacteria from a surface and culturing them on a petri dish to count colony-forming units54. Additionally, understanding the distribution of bacterial adhesion on the surface is vital for elucidating the underlying mechanism. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a useful method for scanning surface morphology in this context144. AFM images not only reveal differences in surface roughness but also provide insight into the colonization patterns of bacteria (Fig. 9b). This result serves as compelling evidence of the antibacterial efficacy of anti-adhesion surfaces. However, it is important to note that AFM cannot distinguish between living and dead cells on the surface. Therefore, to assess both the distribution and viability of the bacteria, fluorescence microscopy can be employed following the staining of bacteria with various fluorescent dyes (Fig. 9c). This method allows for a more comprehensive understanding of both the distribution and survival of bacteria on anti-adhesion surfaces.

Additionally, evaluating surface properties such as surface charge, wettability, and topography indirectly indicates a material’s capacity to resist bacterial adhesion31,44. Since bacteria generally carry a negative charge in aqueous environments, surfaces with a negative charge tend to attract fewer bacteria compared to those with a positive charge, primarily due to electrostatic repulsion. Conversely, surfaces with high positive charges potentially disrupt cell membranes, a phenomenon particularly impactful on Gram-negative bacteria that have thinner cell walls. This understanding underscores the importance of characterizing these surface properties to predict and enhance the anti-adhesion capabilities of various materials.

In general, increased surface hydrophobicity tends to slow down the movement of bacteria as they approach the surface. Simultaneously, a higher degree of hydrophobicity can marginally extend the duration of bacterial collision with the surface, potentially facilitating their adherence145. However, contrasting studies indicate that bacteria are more likely to proliferate on hydrophilic surfaces146. While initial adhesion may be more readily achieved on hydrophobic surfaces, hydrophilic surfaces create conditions that are more favorable for the growth of certain bacterial communities. This is particularly relevant for bacterial species like S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, which tend to form colonies more efficiently on hydrophilic surfaces147,148.

The Extended Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek (XDLVO) theory plays a pivotal role in assessing the likelihood of bacterial adhesion at the initial stage146,147. This theory is utilized to calculate the total energy required to transport bacteria from an infinite distance to a surface, considering factors such as surface charge, wettability, and surface-free energy. The total free energy is conceptualized as the cumulative effect of Lifshitz-van der Waals forces, polar interactions, and electrical double-layer interactions. While XDLVO theory provides an estimate of the energy needed for initial adhesion, it is important to note that bacteria are complex living organisms, and their behavior may not align perfectly with theoretical predictions. Furthermore, the XDLVO theory traditionally assumes surfaces to be completely smooth and uniform. However, surface morphology is a significant factor influencing bacterial adhesion149. Although rough surfaces cannot be directly analyzed using XDLVO theory, the impact of surface roughness on bacterial adhesion can still be examined. This is achieved by integrating the surface element method with the XDLVO approach, allowing for a more comprehensive analysis that accounts for the influence of surface topography.

Currently, the performance evaluation method focuses on surface microorganism count and observation. However, the application of theory could offer theoretical guidance to evaluate the anti-adhesion performance of biofilm, thus achieving the optimization of nanomaterial.

Challenges and perspectives

The above discussion proves that the application of nanomaterials in improving antibiofilm performance is promising, but critical issues still limit the application. Major limiting factors include high cost, durability issues, toxicity issues, mass production, recovery, and reuse.

1. Cost issues. While nanomaterials currently offer superior antibacterial effects compared to traditional disinfection and sterilization methods over conventional disinfection, their application cost remains relatively high. Advancements in fabrication and modification technology are gradually reducing production costs, enhancing the feasibility of nanomaterial applications. Additionally, novel anti-adhesion nanomaterials demonstrating long-term, sustained antibacterial effects are high cost as well. To further reduce operational costs, combining nanomaterials with chemical disinfectants presents a promising, cost-effective approach for specific applications, such as drinking water and wastewater systems.

2. Durability issues. Longer use can be achieved by addressing the inevitable microbial attachment, such as removing microorganisms from surfaces through combined processes. For instance, wrapping bactericidal material around anti-adhesion surfaces allows for the release of bactericidal substances when attached microorganisms alter the surface environment. However, this approach typically results in a one-time removal of attached microorganisms, and achieving reuse remains a challenge. Additionally, traditional sterilization methods can help reduce biofilm attachment, thereby extending the service life of nanomaterials due to a more favorable external environment and lower microbial density. Furthermore, integrating monitoring methods with combined antibiofilm systems offers a more reliable way to enhance the durability of nanomaterials in practical applications.

3. Toxicity issues. Some nanomaterials still rely on the release of potentially toxic substances (e.g., ions) for antibacterial purposes. Additionally, regulating biofilm growth by manipulating the microenvironment, such as adjusting pH changes caused by microbial metabolism, helps strengthen control and minimize unnecessary release. Moreover, methods of external stimulation, such as precisely controlled electrical energy, effectively halt the release of harmful substances.

4. Mass Production. Many cutting-edge materials require highly sophisticated synthesis methods, such as electrochemical techniques, hydrothermal processes, or high-temperature and high-pressure environments. As a result, it is often impractical for manufacturers to adopt these advanced technologies on a large scale. Without industrial partners willing to utilize novel materials, these innovations remain confined to the laboratory, with limited potential for societal impact or economic benefits. Another significant challenge is ensuring that mass-produced materials maintain the same quality as those produced in controlled laboratory environments. As fabrication scales up, new uncertainties arise, such as difficulties in maintaining uniform temperature distribution in large furnaces. Therefore, collaboration between materials scientists and equipment engineers is essential to develop and optimize production equipment capable of meeting the stringent demands of mass production.

5. Recovery and Reuse. While nanomaterials are inherently expensive, their cost can be mitigated through efficient recovery and reuse strategies. However, this presents a significant challenge. The high surface area, a key characteristic of nanomaterials, often necessitates their use in slurry reactors, where nanoparticle powders are introduced into the reactor chamber for water treatment. Filtration and sedimentation are the most common recovery methods, yet they are associated with considerable material loss (often exceeding 10%). Techniques such as magnetic nanoparticle separation and electrophoretic methods have been developed to address these inefficiencies, but the recovery rate remains a critical area of investigation. Enhancing recovery efficiency is essential for reducing the long-term cost of nanomaterial applications in industrial settings. Another critical aspect is reuse. The activity of nanomaterials, such as their catalytic reactivity or adsorption capacity, tends to degrade after each use. Therefore, effective regeneration of these materials is crucial. Several factors must be considered, including the accessibility and affordability of regeneration equipment, ease of operation, and overall cost-effectiveness compared to purchasing new materials. Additionally, the regeneration process must be environmentally sustainable, minimizing the generation of hazardous waste.

Conclusion

This review comprehensively explores the potential of nanomaterials in enhancing antibiofilm performance through both physical and chemical means. In terms of physical approaches, mechano-bactericidal surfaces leverage mechanical forces to disrupt and kill bacterial cells. While they offer safety and non-toxicity, challenges remain in maintaining surface cleanliness and optimizing nanostructure parameters for maximal efficacy. Characterized by high surface roughness and low energy, superhydrophobic surfaces effectively reduce bacterial adhesion. However, their performance is limited in submerged environments. Combining superhydrophobic surfaces with other antibacterial strategies, such as silver nanoparticles, can enhance long-term efficacy. Superhydrophilic surfaces repel bacterial colonization and exhibit self-cleaning properties, significantly enhancing biofilm inhibition. Nonetheless, their susceptibility to corrosion and the need for improved stability are areas for future research. The acoustic method disrupts cell membranes and generates ROS. Enhancements with sonosensitizers and the incorporation of nanozymes for oxygen regulation are promising, though energy optimization remains a challenge. Direct and indirect mechanisms of electrostimulation show high effectiveness in bacterial removal. Combining electrostimulation with nanomaterials can enhance efficacy and control the release of ions, extending service life and broadening application potential.

In terms of chemical approaches, Metal-based nanomaterials release positively charged ions to exert antibacterial effects. While effective, concerns about human toxicity necessitate controlled release and functionalization to enhance biosafety. Nanomaterials facilitate ROS production, disrupting bacterial cells and degrading biofilm components. Combining ROS generation with other antibacterial strategies can amplify effects, though challenges with ROS lifespan and diffusion distance persist. Nanomaterials inhibit efflux pumps, enhancing antibiotic effectiveness and reducing biofilm formation. This dual benefit underscores the potential for integrated antimicrobial strategies. By disrupting nutrient processing and essential metabolite synthesis, nanomaterials effectively hinder bacterial growth. The geometric properties of nanomaterials play a crucial role in their antibacterial efficacy.

This review highlights the transformative potential of nanomaterials in biofilm control, offering insights crucial for advancing sustainable and effective antibiofilm strategies across various fields, including natural and engineered water systems. Considering the limitations of current nanotechnology in combating biofilms, it is essential not only to continue exploring the properties of nanomaterials but also to foster collaboration among various mechanisms and integrate traditional methods as effective strategies to address these shortcomings. The integration of nanomaterials into existing frameworks represents a significant step forward in mitigating the pervasive challenges posed by biofilms.

Responses