A review of micro-resolved crystochemical and mechanical probes for sustainable cement-based material studies

Introduction

Cement and concrete are ubiquitously used for modern construction. The most widely used cement—the ordinary Portland cement (OPC)—leaves a carbon footprint of ~0.8 kg CO2 /kg of cement1,2, and accounts for nearly half of the embodied carbon in concrete3. At a global production of nearly 30 giga tones per year, the manufacturing of concrete solely accounts for ~8% of global anthropogenic CO2 emissions4. This pressing issue has driven a recent trend in exploring innovative approaches to enhance the sustainability of cementitious materials.

Researchers and engineers have explored multiple sustainability approaches5,6,7. In the life cycle sequence of concrete manufacturing, these approaches include: (1) producing cement at less CO2 emission8, (2) developing low-carbon cement (including blending with new supplementary cementitious materials (SCM))9; (3) utilizing waste and low-grade materials as concrete constituents10 ; (4) design optimization to use less cement11, (5) CO2 utilization (in preprocessing wastes and curing of concrete)12, and (6) elongating the durability of concrete structures13.

For example, limestone combined with calcined kaolinitic clay are intensively studied as a new SCM14. The utilization of low-grade materials (marine clay, municipal waste incineration ash, steel slag, sea sand, seawater) and recycled materials (e.g., recycled aggregate, glass powder, fiber, and rubber) have gained attention, offering promising alternatives to conventional resources. Studies focusing on the carbon capture usage and storage (CCUS) processes within cementitious materials have emerged as another significant area of interest. By sequestering carbon dioxide during concrete production (whether through the pre-treatment of recycled cement paste with accelerated carbonation or the application of early-age carbonation curing to cement-based composites after mixing), these approaches contribute to reducing the carbon footprint of concrete, aligning with global efforts to combat climate change.

Extending the service life of concrete serves as another straightforward pathway to reduce environmental impact and achieve sustainable development of cementitious materials. To achieve this, the first step is to understand the mechanisms underlying concrete degradation, e.g. chloride-induced corrosion of steel bars, sulfate attack, alkali-silica reaction (ASR). In recent years, durability research has made great progress, offering valuable insights that guide the development of sustainable materials in concrete.

Despite these promising prospects for sustainable construction, there exist considerable challenges in optimizing these materials/techniques effectively, where microscale probes play as a vital role in charactering the structure/composition of raw materials and blended cement paste at the nano- and micro- level. Moreover, these probes offer valuable insights into the fundamental mechanisms governing the performance of these materials, thereby facilitating a more comprehensive understanding that can steer the development of robust and durable sustainable construction materials. Taking cement carbonation as an example, although the chemical reaction itself is simple, its kinetic process and the morphological changes of the reactants and reaction products involved, as well as the possible durability issues coupled by changes in the chemical environment of the cement paste are very complex. The introduction of other materials, such as sea sand, further complicates this process.

This review aims to provide a survey of the characterization tools that are able to provide micro-resolved chemical, mineralogical and morphological information. Their advantages will be discussed through examples of application in studying the abovementioned sustainability related work. We will focus less on conventional topics such as OPC hydration and high-performance concrete development. We aim to provide a comprehensive review of the sample conditions and measurement procedure, to enable readers to plan for their own measurements using these methods. The manuscript is structured in three main sections:

-

I.

A review of widely accepted laboratory-based morphological & crystochemical probes, detailing essential sample preparation and interpretation methods. It also discusses recent developments in concrete technology using these techniques, analyzing the microstructural and chemical changes resulting from sustainable material modifications to explain the underlying mechanisms.

-

II.

A review of synchrotron radiation-based morphological & crystochemical probes, including micro-resolved spectroscope, diffractometer and imaging methods. Details of sample preparation, especially for cementitious materials are provided. Examples of these methods applied in studying low-carbon cement/aggregate alternatives and concrete degradations are provided and discussed. Compared with conventional laboratory methods, the advantages and disadvantages of synchrotron-based methods are analyzed.

-

III.

A review of commonly used micro- and nanoscale mechanical testing methods, outlining the necessary sample preparation requirements to assist readers in conducting experiments. The latest progress in sustainable materials for concrete is evaluated, examining how modifications impact mechanical properties after material modification to explain the underlying mechanisms.

At the end of each session, we critically analyzed the strengths and weaknesses of the discussed characterization methods. Finally, we concluded the paper by summarizing the advancements in micro-resolved characterization tools and their impact on understanding sustainable cement-based materials, highlighting the integration of advanced techniques and AI-algorithms to enhance data analysis and suggesting future directions for exploring the microscale processes and mechanical behaviors.

Laboratory-based morphological and crystochemical micro-probes

Concrete is an inherently complex and heterogeneous system, which could be further complicated by the addition of sustainable materials. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the viability of these sustainable materials and to mitigate their potential adverse effects on concrete properties, it is necessary to quantitatively characterize the raw materials and evaluate their influence on the microstructure development and long-term performance of blended cement paste. In this section, we explored advancements in several lab-based nano-microprobes that have gained widespread acceptance, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray computed tomography (X-CT), micro-Raman imaging, and micro-XRF (µXRF). These techniques offer a wide range of image resolution capabilities, spanning from ~1 Å to several micrometers, enabling the acquisition of structural and chemical information about cementitious materials. The sample preparation and result interpretation methods, together with their pioneering applications in sustainable materials within the concrete technology domain are discussed. Notably, this section also recognized the rapid evolution of artificial intelligence, with a particular focus on deep learning-based image analysis techniques. These advancements offer the potential for more robust and quantitative data processing, further enhancing our understanding of the complex relationship between sustainable materials and concrete.

Principles of application

As shown in Fig. 1, most imaging techniques work with focused electron beam or electromagnetic waves, whose wavelength determines the spatial scale of the observation15,16. The theoretical resolution reduces along the increase of wavelength of the applied radiation. As can be seen from Table 1, the resolution of the abovementioned imaging techniques are as follows: TEM > SEM > X-CT > micro-Raman ≈ µXRF.

Images adapted from refs. 15,16,26,29,64,103,209.

For SEM, three signals induced by electron collisions, including secondary electrons (SE), backscattered electrons (BSE) and characteristic X-rays, are most widely used to comprehensively analyze the target material. Correspondingly, the near-surface topography information, phase assemblage and chemical composition can be visually illustrated by scanning the electron beam over the specimen’s surface in a raster and using the signal detected at each point to give the intensity of the corresponding pixel in the image16.

In comparison, with the utilization of much thinner sample and electron beam with higher energy, the most important signal of TEM is the transmitted beam of electrons which have undergone minimal energy loss as they traverse the sample. Compared to SEM, the resolution of TEM is an order of magnitude higher. TEM operates in two primary modes: bright field and dark field. In the bright field mode, the image is formed by the unscattered (transmitted) electron beam, highlighting containing crystalline or high-mass materials by rendering them darker. Dark-field mode, on the other hand, selectively captures scattered electrons, rendering areas without scattering black and materials brighter. Beyond imaging capabilities, TEM offers a multifaceted toolkit for probing crystallinity, elemental composition, and chemical state with selected area electron diffraction (SAED), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS).

X-ray CT is a powerful tool that enables researchers to quantitatively explore the internal structures (e.g., shape, size, orientation, and connectivity) of cementitious materials in a non-destructive, three-dimensional manner. X-ray CT’s operation involves projecting X-ray beams through the target, depending on the linear attenuation coefficient (LAC) of the sample, from multiple angles. Then, hundreds (or even thousands) of 2D attenuation maps are reconstructed into 3D volume with the help of image reconstruction algorithms. To further improve the resolution of X-ray CT and minimize the effect of unevenly distributed X-ray in space and polychromatic X-ray signals, synchrotron-based X-ray CT, or the so-called nXCT, has achieved a remarkable improvement over the past decade17. More detailed features at resolution of ~20 nm inside hydrated cement paste can be captured by nXCT.

Micro-Raman imaging is a high-precision application of Raman spectroscopy that allows the mapping of different phases in heterogeneous materials and has been extensively used to characterize cement clinker phases, study cement hydration and durability. The working principle of Micro-Raman microscopy is grounded in the Raman effect. When a monochromatic light source, typically a laser, illuminates a sample, a small fraction of the incident photons undergoes inelastic scattering. This scattering process causes a shift in the energy levels of these photons, and this energy shift reveals crucial information about the chemical composition and molecular structure of the material under examination. By analyzing the positions, intensities, and shapes of these peaks, researchers can identify the chemical compounds present, study molecular interactions, and gain insights into crystallography and material quality. Compared to the SEM-EDS that can also map the chemical composition of target material, Micro-Raman microscopy is suitable for a wider range of sample types, including liquids, gases, and solids. Moreover, it can be used to easily visualize larger mm-scale maps at micron-scale resolution18.

μXRF is a non-destructive X-ray based imaging technique that simultaneously provides chemical composition and position within concrete samples. It works by utilizing the principle of X-ray fluorescence, which occurs when a sample is irradiated with high-energy X-rays. By scanning the X-ray beam across the sample and measuring the emitted X-rays at each point, a spatial map of elemental distribution can be generated. This provides information, on a wide range of sample sizes from hundreds of micrometers to several centimeters, about the distribution and concentration of various elements within the sample. μXRF can be used to analyze a variety of large specimens (>10 cm2) without many of the limitations found in electron-excitation sources, such as the ability to work at atmospheric pressure and lower limits of detection19.

Sample preparation

Prior to imaging acquisition, proper sample preparation is necessary to align the sample with the specific testing requirements and improve the quality of the resulting images. Broadly speaking, the sample type can be classified as dry sample and wet sample depending on whether free water is removed. All the imaging techniques we discussed here can be applied for in situ testing. While for SEM and TEM, specialized chamber and/or detector are needed. Here, we focus mainly on the most commonly used ex-situ testing conditions, where dehydrated or dried samples are tested.

Compared to conventional oven drying, the substitution of water with isopropanol has been identified as a method that can minimize the damage to C-S-H, and has been widely adopted for the preparation of SEM/TEM samples20. Besides, supercritical drying (SCD) method21 and freeze-drying method22 have also demonstrated their suitability for SEM/TEM sample preparation, effectively mitigating the impact of dehydration on the microstructure of cementitious materials.

SEM

Two types of SEM samples, i.e., fracture sample and polished sample, have been utilized to analyze the morphology and phase distribution of the hydrated cement paste. The corresponding image resolution differs significantly, due to the different beam sources, as <1 nm for fractured sample (secondary electron) and >500 nm for polished sample (backscatter electron). Generally, fractured samples are suitable for unhardened systems. By immersing cement powder in excess isopropanol for a few minutes, subsequently filtering the isopropanol and repeating this process for three to four times, the hydration reaction can be quickly terminated. This approach proves effective in preserving the sample’s state at a specific hydration stage, enabling detailed analysis of the microstructure. At later age, fracture surface of hardened cement paste exists low representative for the overall microstructure since the sampling process could induce man-made damage and break the fragile structure. In that case, backscattered electron imaging of polished surfaces over a wide range of magnifications can be used for phase assemblage and defect analysis23. Considering the relatively big volume of bulk paste, a protocol of immersing the sample in isopropanol for 5–7 days typically proves sufficient16. In addition to isopropanol replacement, other methods, e.g., supercritical drying (SCD)21, freeze-drying24, have also been reported and applied in microstructure sample preparation. A detailed sample preparation procedure is illustrated in Fig. 2, involving sample cutting, vacuum impregnation, polishing, cleaning, drying, etc. Considering the significant resolution difference between fractured and polished samples, the most critical question that needs to be answered prior to SEM sample preparation is: what is the target research object? For morphology study of specific hydration product (for example, C-S-H gel), SE mode of SEM with fractured sample should be prepared. For statistical analysis of the overall hydration products, BSE mode of SEM with polished sample should be prepared. To further improve the image quality and minimize the charging effect, a thin layer of conductive material (e.g., carbon, gold, and iridium) is finally coated before SEM observation. The coating quality is closely related to the sputter target materials, vacuum level, layer thickness, etc. According to previous research25, the grain size of frequently used sputter materials is as follows: Au>Pt>Ir>W. Therefore, for high-resolution morphology observation, Pt and Ir coating with ~5-nm thickness is suggested. As for BSE image acquisition, a thicker layer of Au and C (~15 nm) can be coated.

a Fracture sample29, b Polished sample210.

TEM

For TEM observation, there are also two types of samples, powder sample and lame sample respectively. For the previous one, suitable for powdered samples (e.g., raw materials, unhardened cement/C3S slurry, synthetic C-S-H), sample preparation is relatively easy and straightforward. A fine grind of the cementitious material to a few hundred nanometers allows electron beam to go through the powder sample. Subsequently, disperse a small quantity of powder sample in a solvent (e.g., water, isopropanol). Following ultrasonic treatment to ensure proper dispersion, a mere drop of the suspension is transferred onto a copper grid. The sample is then dried, with freeze-drying being a preferred method when feasible, and ready for TEM observation. For the preparation of TEM lamellae of bulk cementitious materials, due to the need for an ultra-thin sample that permits electron transmission, more extensive experimental efforts are needed. Generally, ion milling, and focused ion beam (FIB) are employed to create TEM lamellae. The detailed sample preparation procedure is illustrated in Fig. 3. Unlike SEM, where the sample surface accumulates excess electrons (known as the charging effect), TEM testing typically allows most electrons to penetrate the sample without charging the surface. Consequently, TEM samples require no additional coating.

Top: grid preparation (for carbonation study)98; middle: ion milling for TEM lamellae (from the website of MESA + INSTITUTE, https://www.utwente.nl/en/mesaplus/nanolab/); bottom: focused ion beam for TEM lamellae60.

X-CT

The foremost advantage of the X-CT test lies in its capacity to non-invasively capture the in situ 3D structure of materials, eliminating the need for special sampling processes. However, it is important to note that, the resolution of X-CT is directly related to the size of the test sample. For example, to achieve a voxel resolution below 100 nm, the diameter of the sample was approximately 100 μm17. As the sample size increases, the resolution decreases accordingly. In practice, the sample size is normally two to three orders of magnitude larger than the anticipated resolutions. Hence, before conducting the test, careful consideration must be taken to calibrate the sample size so as to balance the resolution with field of view, while aligning with the capabilities of the equipment in use.

Depending on the purpose of the experiment, X-CT sample can be prepared by casting in a certain shape for direct measurement (mm size samples for microresolution, samples in capillary for sub-microresolution), drop-casting of powders on sample holder (coper grid or film transparent to x-ray), cutting (macro-cutting using a high-precision cutting machine, micro-cutting using FIB). Moreover, except ambient condition, controlled environmental conditions26 (e.g., temperature, relative humidity, and gas) and loading27 can be applied to the sample, which enables researchers to monitor the 3D structural changes in real-time, facilitating in situ investigations of the sample’s response over time.

Micro-Raman and micro-XRF

Both micro-Raman and μXRF tests offer the advantage of being applicable to freshly cut cementitious samples without extensive human intervention. However, the signal quality can be notably improved by subjecting the samples to gentle drying and surface grinding/polishing prior to analysis28. This process closely resembles the sample preparation method employed for SEM polished samples, involving epoxy resin impregnation and a step-by-step polishing procedure.

It’s worth noting that both micro-Raman and μXRF techniques demonstrate a lower sensitivity to surface roughness when compared to SEM-BSE imaging. Consequently, a comparatively lower degree of precision in the polishing process (normally hand polishing with sandpaper) is acceptable, implying a higher tolerance for sample preparation in these techniques. This attribute simplifies the sample preparation process and contributes to the efficiency and practicality of these analytical methods.

Result interpretation

Image processing plays a pivotal role in extracting valuable qualitative or quantitative information from the original image. In many cases, the analysis of the images could be more time-consuming than the image acquisition itself because of the huge size of the dataset intricacies involved in imaging processing procedures.

For SE-SEM, the output is mainly surface topography information, readily discernible to the naked eye. Though point-specific analysis with SE-SEM provides high-resolution and detailed morphological information, it has limitations in providing a comprehensive statistical overview of bulk paste. As emphasized by Scrivener et al.16 the inherent limitation of SE images lies in their predominantly qualitative nature, often demanding subjective interpretation. To facilitate statistical analysis, it is necessary to compare multiple SE images with specific targets29,30. Similarly, 2D TEM images provide insights into the internal structures and morphologies of specimens. However, to mitigate the subjectivity in observations, it is essential to compare multiple TEM images.

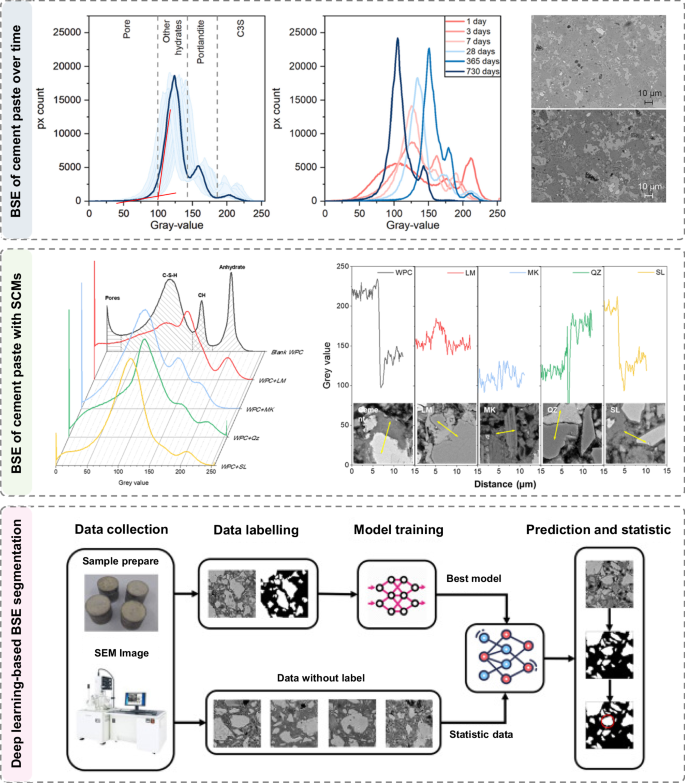

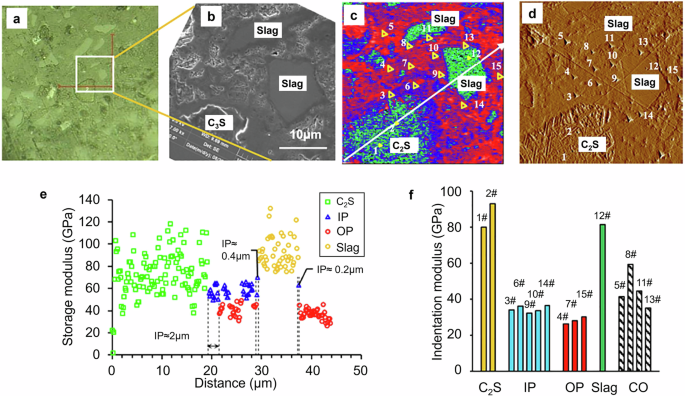

For BSE image, the greyscale value of each pixel is determined by the average atomic number of phases within the interaction volume, which helps to distinguish hydration products and blended materials in the cement paste. Note that the size of the interaction volume in BSE is directly related to the accelerating voltage. To ensure a robust electron signal intensity for imaging, the recommended setting is 15 kV. Consequently, the resolution of the BSE image is no higher than 500 nm. Therefore, for fine particles and phases that are heavily intermixed with calcium silicate hydrate (e.g., ettringite) on a scale smaller than the interaction volume, it is impossible to visually differentiate and segment them31,32. For the other phases present in hydrated cement paste, e.g. anhydrous cement, portlandite, C-S-H gel and pore, the corresponding areas can be segmented from BSE image based on the greyscale histogram. Then, the critical question is, how to set the threshold value for a specific phase? The most widely used method is the tangent-slope thresholding method proposed by Scrivener et al.33, which can effectively segment anhydrous cement particle and pores (Fig. 4 top). Yet, the introduction of Supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) complicates matters as the greyscale characteristic peaks tend to overlap significantly, blurring or fully eliminating phase distinctions. In such cases, the tangent-slope thresholding method is no longer applicable (Fig. 4 middle). Recently, thanks to the development of computer vision techniques, especially deep learning-based image analysis methods, a range of phase segmentation algorisms have been developed to quantitatively analyze the BSE images of cementitious materials. By manually labeling the target phase in the BSE image and feeding the well-labeled image pairs, including both the raw image and labeled mask, to deep learning algorisms (e.g., ResNet34, VGG35, and DenseNet36), the features of the target phase can be captured over the training process (Fig. 4 bottom). These methods offer more robust and statistical phase assemblage analysis, often yielding results comparable to those obtained through quantitative X-ray diffraction (QXRD)37,38,39,40,41,42,43.

Tangent-slope thresholding method can be used to segment anhydrous cement and pores in blank cement paste, while deep learning-based image segmentation method shows great potential in segmenting heterogeneous cement paste. Images adapted from refs. 37,43.

For SEM/TEM EDS, micro-Raman, and μXRF images, the source of image contrast originates from different chemical compositions. Hypermaps of individual elements can be created according to the element distribution in the sample and overlapped with the original image to illustrate the distribution of different phases in the heterogeneous matrix. Recently, Georget et al.44 developed a user-friendly image analysis framework Edxia to identify phases and quantify the microstructure of cementitious materials from SEM-EDS hypermaps. In addition to individual element maps, element ratios (e.g., Si/Ca, Al/Ca, S/Ca, Cl/Ca) can be easily calculated and treated as extra feature maps for phase segmentation.

Like the process used for SEM-BSE image analysis, a parallel approach is employed for interpreting X-CT data before reconstructing the 2D slices into 3D volumes. Depending on the number of target phases (e.g., aggregate, hydrates, pores, and cracks) inside the sample, the raw 2D slices need to be converted into multiple masks plus the background. Due to the low contrast of phases in X-CT images, remember in situ X-CT test without stopping hydration, and relatively low beam powder as lab-based micro-CT, the image analysis can provide differing results based on the procedures followed without careful evaluation45. Moreover, considering the hundreds or even thousands of 2D images for one sample, the traditional CT scanning image segmentation methods cannot effectively identify and segment phases autonomously, which further lowers the accuracy of X-CT reconstruction. To mitigate this challenge, employing a limited number of annotated CT images for neural network training proves to be a promising solution. The neural network autonomously learns and adapts to recognize distinct features, enabling automatic segmentation of the remaining images based on these extracted features. This method can not only avoid the fluctuations and errors that may exist in manually adjusting the threshold parameters of many images, but also greatly save time and cost, making the processing of CT data accurate and efficient. Deep learning analysis has been used for CT analysis including identification and reconstruction of concrete mesostructure46,47, identifying the micro and meso-damage of concrete48,49, and multi-mineral segmentation of rock micro-CT images50.

Applications in sustainable materials in concrete technology

Supplementary cementitious materials

The utilization of SCMs as a partial replacement for cement stands out as a highly effective and straightforward approach for mitigating the carbon footprint of the cement industry51. Nevertheless, SCMs typically originate as by-products of industrial processes, often featuring multiple impurities and exhibiting variable physical and chemical properties. In this context, SEM and TEM have emerged as essential tools for characterizing the surface morphology of SCMs (e.g., fly ash52,53, slag54,55,56, calcined clays57,58,59), as well as investigating their reaction mechanisms55,60,61,62,63. Polavaram et al.64, conducted comprehensive testing on eight secondary phases present in cement clinkers (gypsum, anhydrite, bassanite, syngenite, dolomite, calcite, quartz, and portlandite) and four principal phases in cement using Raman imaging. Their work demonstrated that Raman imaging is also a highly versatile tool for anhydrous phase quantification in a broad variety of cements. Even though, accurately estimating the reaction degree of amorphous SCMs within hydrated cement paste has long posed a significant challenge. In this regard, as illustrated in Fig. 5, the combined use of BSE image analysis, EDS mapping, X-CT, and micro-Raman has made it possible to quantify the DoH (degree of hydration) of slag42,65,66,67 and fly ash68. Generally, the chemical composition of SCM is significantly different from that of cement clinkers and hydration products. By determining the characteristic element of SCMs (e.g., Mg for slag) and overlapping the elemental map with the BSE image, it will be much easier to set the threshold value of the target phase and calculate DoH according to the segmentation result than that of greyscale value-based BSE image analysis. While it should be noted that a relatively big error still exists.

For slag, fly ash and AFm respectively65,68,78.

Generally, within a certain threshold of substitution rate for SCMs, the presence of intermixed hydrate gels that incorporate foreign ions from SCMs (e.g., Na+, Mg2+, Al3+, K+, and Fe3+) has proven to be advantageous for fostering the development of a more compact microstructure55,56,60,69. This enhanced microstructure, despite an increasing number of pores, results in the refinement of the pore network70,71. Consequently, a reduction in the permeability and ionic diffusion of the concrete can be achieved. However, in specific instances, such as alkali-activated slag cement doped with Zn-rich electric arc furnace dust (EAFD)54, where only 5% of the slag is replaced with EAFD, a more porous and heterogeneous structure can be formed. Despite this porosity, it is noteworthy that heavy metal ions, such as Zn, Cr, and Pb, can be chemically incorporated into the reaction products, offering a viable solution for the disposal of these hazardous materials.

Such good performance in solidifying hazardous industrial by-products, including heavy metals and radioactive wastes, is mainly due to the porous structure and highly charged surface of C-S-H gel, where heavy metals (e.g., Cu, Co, Cr, and Zn) can be incorporated on the surface or within the defective layered structure at nanoscale44,54,72,73. Specifically, Baldermann et al.73,74 systematically studied the immobilization mechanism of heavy metals (e.g., Co, Cr, and Zn) with TEM images and EDS spectra, revealing that the immobilization mechanism of heavy metals in the C-A-S-H system is based on a combination of isomorphous substitution, interlayer cation exchange, surface (ad)sorption, and surface precipitation. Furthermore, in the case of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash (MSWIFA) with high chlorine (Cl) and lead (Pb) content, HAADF-STEM (High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy) imaging and element mapping, confirm not only a simple ion-exchange behavior between Pb and Ca but also a complex Pb-Cl synergistic immobilization process75,76.

In recent years, limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) has been developed as a promising blended cement with comparable performance as OPC but a much lower carbon footprint. With up to 50% replacement of OPC – a substitution rate significantly higher than that of traditional SCM—by limestone and calcined clay, LC3 exhibits similar compressive strength to the blank cement system after 7 days and offers improved durability in terms of chloride and ASR resistance77. Calcined clay is considered the critical material determining the overall properties of this ternary system. The interaction of metakaolin with limestone in LC3 results in the formation of more hemicarboaluminate and monocarboaluminate, a phenomenon observed through SEM-EDS mapping. This reaction leads to a space-filling effect that significantly refines the porosity, aids in strength development, and provides superior resistance to chloride ion penetration compared to other blended cements78. Interestingly, except for kaolinite content, the calcite impurities in a kaolinitic clay can also affect the mineralogy and reactivity of calcined clay. SEM observations by ref. 58 demonstrated that a granular deposit originated from calcite impurities can partially cover the kaolinite particles to reduce the specific surface area of calcined clay, which increases with the amount of calcite that is intermixed in the raw clay. To optimize the performance of LC3, multiple factors, including clay quality, particle size, and calcination conditions, must be thoroughly considered.

Unconventional concrete constituents

The growing demand for sustainability and green concrete has driven the exploration of novel SCMs and some unconventional materials, especially recycled ones. In contrast to traditional SCMs, the physical and chemical composition of these materials are even more complicated, yet they remain relatively underexplored in terms of their potential impacts on the properties of hydrated cement paste.

Sea sand and seawater are increasingly used to mitigate the shortage of natural river sand and freshwater. Dhondy et al.79 highlighted that the chemical (e.g., impurities with foreign ions like Mg, Al, K, and Fe) and physical (e.g., mineralogy and particle size distribution) properties of sea sand is highly variable, as shown in Fig. 6 top. This variability has contributed to fluctuating and, in some cases, contradictory findings in studies investigating the impact of sea sand on concrete properties. Instead of directly using the raw sea sand, using desalinated sea sand, with less impurities and reduced chloride content, to produce desalinated sea sand concrete (DSSC) has been a viable solution, particularly in coastal areas and remote islands. Even though, as certain amount of chloride still exists in the DSSC, the risk of chloride-induced corrosion of the steel reinforcement cannot be ignored80. Regarding seawater-mixed concrete, SEM and TEM observations suggested that the seawater-hydrated cement matrix was enriched with more cement hydrates, finer microstructure, and higher crystallinity compared to the DI water-hydrated cement matrix (Fig. 6 bottom), leading to a 50% increase of 28 d compressive strength and highly reduced autogenous shrinkage81.

Bottom: impact of seawater on the microstructure of hydration products characterized by SEM and TEM81.

Multiple recycled materials, e.g., recycled aggregates82,83,84, glass powder85, carbon fibers61,86, rubbers87,88, biochar89,90, have been utilized to prepare concrete. Due to the rough and/or inert surface, a more distinct interfacial transition zone (ITZ) can be found in systems mixed with recycled materials, which could bring a negative impact on the overall property of blended concrete91,92. As summarized in Fig. 7, X-CT has demonstrated its suitability as an imaging technique for the quantitative analysis of the mesostructure of cement paste/mortar, with a particular focus on the ITZ that interfaces between the recycled materials and the fresh paste/mortar. Furthermore, the application of X-CT, in conjunction with BSE imaging and EDS mapping analysis, allows for the detailed examination of the chemical composition and porosity of the ITZ93.

a Recycled aggregate concrete84, b Biochar blended cement paste90, c Opalinus clay (OPA) and concrete93. Images adapted from refs. 84,90,93.

Chen et al.84 discovered that the interface region thickness between recycled aggregate (RA) and new mortar is about 200 μm, and the crack width in recycled aggregate is about 300–400 μm. For the microstructure, ref. 94 observed that the surface area of recycled aggregate exhibited characteristics of slurry, loose, porous structure, and could not effectively bear loads owing to its poor mechanical properties. However, the application of carbonation treatment to RCA has been found to enhance the properties of the weak ITZs in RAC, consequently improving the overall behavior of RAC95. Specifically, it can be seen from SEM images that there are many lamellar Ca(OH)2 crystals in ITZ before carbonation, which show an accumulation distribution. However, lamellar Ca(OH)2 and flocculent C-S-H can hardly be found in ITZ after carbonation, and ITZ is filled with small particles of CaCO3 after carbonation, which contributes to a more compact microstructure and an increase in the elastic modulus.

Zhao et al.85 conducted a quantitative analysis of the porosity and chemical composition of the ITZ in recycled concrete enhanced with waste glass powder (WGP). Their research revealed that WGP effectively reduced the volume fraction of pores and cracks through a reaction with calcium hydroxide (CH) within the new ITZ and the adjacent old mortar. This reaction generated a significant quantity of C-S-H gel with a Si/Ca ratio of ~1.5. Similarly, with the addition of biochar, a higher compressive strength than the estimated values based solely on the increased porosity can be achieved89. The main reason for this phenomenon, as revealed by EDS mapping and X-CT, is the bonding of biochar particles with hardened cement matrix via a layer of Ca-rich hydration products (~50 um) mainly composed of AFm phases, CH and C–S–H gels90.

Rubber-cement composites are composed of elastic rubber particles and brittle cement-based materials, and their internal structures and ITZ are more complicated than the abovementioned systems. Analysis of the BSE images clearly reveals the weakness in the interfacial bonding between rubber particles and mortar, resulting in a notable reduction in compressive strength. With certain surface treatments (e.g., silica fume coating), low Ca/Si gels, as confirmed by SEM-EDS analysis, can be formed at the rubber-mortar interface, which improves the mechanical strength of rubber concrete88. Yet, when attempting to characterize rubber-cement composites using X-CT, a unique challenge arises. Since the pores and the rubber particles have very similar gray values in the X-CT image, grayscale thresholding alone is insufficient for distinguishing between the two phases. To address this issue, the incorporation of additional shape-based characteristics, such as size, shape, and roughness, becomes necessary to accurately identify the rubber particles27.

For recycled carbon fiber, reduced pullout and higher tensile strength, indicating improved bonding due to compatible sizing and rough surface morphology compared to the new carbon fiber, can be found61,86. The main issue for recycled carbon fiber is the reduced workability of the reinforced mix compositions. Moreover, pore formation and poor fiber distribution, as can be clearly visualized by X-CT61, can significantly affect the mechanical properties.

CO2 mineralization mechanism

Carbonation of cementitious systems is a phenomenon, significant from both durability, with implications for rebar corrosion, and environmental perspectives, given its potential for greenhouse gas emission reduction through CO2 sequestration18. All of these activities involve complex physical and chemical changes that are accompanied by dynamic microstructural changes, which extend beyond what can be adequately elucidated through bulk measurements, such as pH variation or calcite content alone.

The morphological changes occurring in cementitious materials during the carbonation process are directly observable through electron microscopy, as illustrated in Fig. 8. Combined with SEM-EDS analysis, the carbonation process of recycled cement paste fine powder (RP) was found to involve two distinct steps83: step 1 featured the presence of Ca-rich residue, manifesting as rhombohedron-shaped calcite crystals, while step 2 was marked by Si-rich gel with agglomerated particles. The particles in the gel products, initially appearing to be of nano size, were significantly affected by agglomeration, leading to changes in their final size. In addition, Zajac et al.96 found that Al and Si from the hydrates do not diffuse out of the grains, instead remaining within the space initially occupied by the hydrates. A significant part of the Al from the carbonation of the ettringite and AFm phases is incorporated into the alumina-silica gel, rather than precipitating as a separate alumina hydroxide gel.

Image adapted from refs. 82,83,97,98.

In the synthetic C-S-H system, similarly, a large amount of calcium carbonate, mainly vaterite, is formed with the generation of modified silica gel after exposure to CO297. Zheng et al.98 employed SEM and TEM to investigate the carbonation process of alite hydrates, revealing that calcite is the dominant phase of carbonate crystals throughout the entire carbonation period in the alite system. These crystals initially formed as spindle carbonates on a C-S-H substrate but eventually evolved into rhombohedron shapes. The growth rate of calcite particles was estimated to be ~0.2 μm/day, potentially influenced by the relative concentration of calcium ions and the CO2 source: A gradual increase in c(CO32−)/c(Ca2+), mainly caused by the variable CO2 migration speed over time, leads to a tendency for calcite to transform from spindle to polyhedron.

Regarding the microstructure of hydrated cement paste blended with carbonated recycled cement paste powder (CRP), Ouyang, et al.82 discovered that strong chemical interactions between CaCO3 and C-S-H facilitated the perpendicular and uniform growth of C-S-H on the surface of CRP. In addition, the alumina-silica gels in the carbonated paste are highly reactive, achieving a complete reaction within 28 days of hydration. These attributes make CRP a promising candidate for clinker replacement in composite cements12.

Raman spectroscopy stands out as a highly effective method for the accurate detection and monitoring of the carbonation process in cementitious materials, as demonstrated in Fig. 9. When subjected to a CO2-enriched atmosphere, Raman spectra analysis consistently revealed a prominent peak near 1090 cm−1, which is a reliable indicator of the presence of calcite18,99. By utilizing standard specimens pre-mixed with defined quantities of CO32−, researchers can initially establish a robust correlation between CO32− content and Raman peak intensity. This correlation enables a quantitative investigation into CO2 ingress and the extent of carbonation within the cement paste100. When considering the temporal aspect, a series of calcium carbonate polymorphs, including disordered calcium carbonate, ikaite, vaterite, and calcite, can be formed at different stages of elite carbonation ref. 101. It is worth highlighting that carbonation can induce chloride redistribution within the paste and accelerate the corrosion of steel reinforcement80. This effect results from the gradual release of bound chloride ions, leading to an increase in the concentration of free chloride ions. In contrast, the carbonation-induced drop in pH value was found not to be the direct cause of the corrosion of the steel reinforcement.

Images adapted from refs. 80,100,101,211.

Long-term durability problems

Compared to the blank cement paste, pastes blended with sustainable materials often pose more significant durability challenges due to the complex hydration kinetics and the emergence of a more heterogeneous microstructure. In this section, we reviewed the long-term performance issues associated with blended cement-based materials.

Degradation of cement paste usually involves ion transport through the cement matrix, changes in the microstructure of hydration products, and the formation of new products, which can be tracked through SEM/TEM imaging and element mapping (EDS, μXRF, and micro-Raman) techniques, as shown in Fig. 10. Traditional methods for assessing chloride profiles in concrete, such as profile grinding, are known to be labor-intensive and time-consuming. To address these challenges, ref. 102 used μXRF to measure chloride penetration depth and calculate the apparent diffusion coefficient. Their findings highlighted the potential of μXRF for efficiently and rapidly evaluating chloride profiles in both laboratory and field concrete over a wide range of chloride penetration depths. Notably, the information obtained through μXRF was found to be equivalent to or even superior to that derived from profile grinding methods. Similarly, with μXRF, Sudbrink et al.103 imaged the change of sulfur and potassium distribution in the cement paste with and without silane coatings in a large scale (cm-level).

The causes are chloride permeation (by uXRF)212, sulfate attack (by SEM-EDS)104, ASR (by SEM)26,105, and chloride-induced corrosion (by SEM)106.

To better reveal the micro-degradation in sulfate attack, ref. 104 developed a novel method to investigate sulfate ion ingress under unidirectional capillary action using BSE imaging and EDS mapping. Operating at a 5 mm-depth scale, this approach allowed for the comprehensive analysis of both phase assemblage and element distribution information. It revealed that physical and chemical sulfate attack occur in different areas of the same sample. Leemann, et al.105 observed the morphology of amorphous and crystalline ASR products with SEM, revealing that the amorphous ASR products are formed initially, leading to aggregate cracking. Subsequently, crystalline ASR products began to fill the open cracks in the aggregates. Comparative observations through a steel-concrete interface and corrosion products from reinforcing steel into concrete revealed that only a small amount of corrosion was needed to induce visible cracking106. Moreover, both BSE imaging and element maps (e.g., Fe, Ca, and O) clearly illustrated a distinct boundary between the affected and unaffected paste areas, providing a visual representation of the extent of the penetration front.

Strength and limitations

As micro and nanoscale experimental probes continue to advance rapidly, the attainment of high-resolution morphological and chemical data from target materials in laboratory settings has become more accessible. The combined utilization of two or more testing methods has the potential to expand the range of measurable information. However, as highlighted by ref. 107, there exists an inherent trade-off between the achievable resolution and image volume, or more succinctly, the statistical robustness of results. Take X-CT as an example, on the one hand, imaging at the millimeter scale enables the capture of microcracks, but may exclude larger cracks, lacking the representativeness necessary for comprehensive analysis. On the other hand, a large proportion of fine microcracks (<10 μm), such as those induced by drying shrinkage, will be excluded if imaging is carried out at cm scale. Similarly, in element mapping, opting for a larger testing area in μXRF conditions necessitates accepting a lower resolution, resulting in the potential loss of localized information. Until now, no single technique exists that can capture the full-size range of features, from nanometers to tens of micrometers, within a sampling volume that is sufficiently representative.

Moreover, the quantitative interpretation of informative imaging data is another crucial aspect demanding greater attention. While a substantial number of BSE images of cementitious materials have been generated, most of them lack detailed quantitative information. Without a standardized protocol for sampling and imaging, considering also the wide variety of sample types and test conditions, cross-comparison between different methods, or even the same method performed by different research groups, is difficult. This lack of standardization leads to underutilization of the generated data, limiting the potential for comprehensive insights, especially the training and application of deep learning models that rely on substantial quantities of high-quality images for effective training. Addressing these challenges is crucial for advancing the field and enhancing the reliability and interpretability of imaging data in concrete research.

Synchrotron radiation-based morphological and crystochemical micro-probes

The phenomenon of synchrotron radiation was first discovered in the 1940s. In brief, it is the generation of electron magnetic waves (e.g., X-ray) when charged particles are radially accelerated108. Synchrotron radiation X-ray is often characterized by extremely high brightness, tunable energy, and high coherence, making it an ideal beam source to develop characterization probes of physical and chemical processes at multiple temporal and spatial scales. After extensive development in the past half century, more than 50 synchrotron facilities (third generation) are now in operation world-wide, serving a broad categories of research fields such as life science, material science, chemical science, geoscience, physics, applied science.

The readers are referred to published books for the basic knowledge of synchrotron radiation108,109. In this chapter, we aim to provide a landscape picture of several synchrotron radiation-based methods that are widely used in the study of cementitious materials. Echoing the theme of this review paper, we only focus on methods with microscale spatial resolution, in particular micro-X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (micro-XAS), micro-X-ray Diffraction (micro-XRD), micro-X-ray 2D&3D imaging methods. These methods have been extensively used to provide microscale chemical, mineralogical, and morphological information of cementitious system in the past decade. We notice that similar review works have been reported previously110,111,112, yet we differentiate ourselves with a focus on sustainable-related studies (such as waste utilization, durability enhancement, carbon sequestration), and the update in the past 5 years.

Principles of application

X-ray interacts with a solid volume in multiple ways (Fig. 11a). It is either transmitted, scattered/diffracted, or absorbed by the solid. Characteristic absorption of x-ray takes place when the incident beam energy is close to the difference between inner orbital electrons and the vacant outer orbitals. Recording the beam intensity loss or the number of emitted electrons yields the absorption spectrum. The x-ray absorption spectrum (XAS) features of an element depend strongly on its chemical environment, making it a fingerprint information for phases either crystalline or amorphous. In a synchrotron XAS beamline the incident x-ray could be focused to micron-size spot which, coupled with a multi-direction sample stage, enables examining the microscale chemical heterogeneity of a solid samples113. This is extremely useful for concrete samples, which are often composed of multiple phases at micronscale. With incident beam energy ranging from 1500 to 4500 eV, elements like Si, Al, S, Cl, K, and Ca could be studied114,115, yielding useful microscale information during concrete degradation. At higher beam energy from 4500 to 10,000 eV, a list of heavy metal elements (Zn, Cu, Co, Cr, etc.) can be studied to track their long-term fate in concrete, which are crucial in the utilization of waste for sustainable concreting116. The XAS of Fe (7000–8000 eV) also provides invaluable data on the microscale formation of transformation of Fe (hydr)oxide species during the corrosion degradation117.

a Illustration of x-ray interacting with a solid sample. Explanation of the ptychographic imaging scheme: b Phase relationship of two overlapped scattering spots; c The overlapping of multiple scattering spots provides robust solution to the phase problem.

XRD is a widely adopted material characterization tool. Benefiting from the high brightness of synchrotron x-ray, micro-focused beam generates XRD data of high signal-to-noise ratio even at single-minute exposure, enabling reliable quantitative analysis from Rietveld refinement118. Debye-Scherer rings recorded on 2D panel detector allow probing the local crystal orientation118,119. Such a micro-XRD probe is a power tool to study localized interaction between crystals.

X-CT is ubiquitously used to probe the 3D structure of cement-based specimens120. In either scanning or full-field projection mode, the transmitted x-ray carries the information of attenuation coefficient. With Fourier Transform-based iterative algorithms, the recorded projection data reproduce attenuation-contrast images, where contrast is more pronounced between regions with different attenuation to x-ray. For cement-based specimens, less porosity and/or higher content of heavy atoms usually result in higher attention. While currently, the most advanced laboratory X-CT provides a 1-μm resolution (usually requiring several hours of scan), focused synchrotron X-ray allows a resolution as high as 20 nm, thanks to the much brighter beam source and smaller beam spot size. The scanning of synchrotron X-CT is also more rapid, e.g., several to tens min per sample, enabling in situ observation of fast-evolving systems.

The limitation of X-ray image resolution is ultimately determined by the spot size of the beam, which can hardly be focused below 10 nm. In the past decade, a new imaging approach named ptychography has been developed in multiple synchrotron facilities. The fundamental of ptychography is to solve the ‘phase problem’: x-ray detectors only record the intensity (amplitude) of the X-ray; hence, its phase information is lost. An X-ray beam is described by a complex number Z since it has both phase and amplitude. When it passes through two overlapped regions, it yields the individual scattering Z1 and Z2, and an overlapped scattering Z1 + Z2. The angle φ between Z1 and Z2 can be solved as it is determined by the edge length of the triangle in Fig. 11b, i.e. the amplitude |Z1|, |Z2|, and |Z1 + Z2|, which are recorded on the detector. What is left unknown is the sign of φ. In a ptychographic scanning, an extensive overlapping between scanning regions is conducted (example shown in Fig. 11c), providing sufficient overlapping intensities to solve the relative phases between adjacent scatterings. Therefore, the limit of resolution is determined by the step size of the sample stage movement, which could be 1–2 nm.

The mathematics behind ptychography was proposed several decades ago121. Due to the limitations of computing power and scanning devices, only until recently, it was extensively developed in several synchrotron facilities122,123. It is also straightforward to conduct a ptychographic-CT scan. Its advantage is not only the improved resolution, but also the capability of phase-contrast imaging, which helps differentiate hydrates in cement paste that have similar attention coefficient and cannot be distinguished using normal x-ray imaging124.

Sample preparation

Samples used for synchrotron microprobes should be prepared at minimal alternation to the microstructure. Drop-cast powder samples and natural (fracture) surfaces can be directly used for observation. Polished surfaces and thin sections are also often used but with careful impregnation of resin to preserve the microstructure during polishing. The samples cannot be too thick if a transmitted X-ray is recorded. For tomographic scanning, the samples need to be thin in the planar direction perpendicular to the rotation axis. Examples are given as follows.

Micro-XAS and micro-XRD

Both micro-XAS and micro-XRD require a relatively flat surface to interact with the incident X-ray. This could be achieved via a polished cross section or a thin section (Fig. 12a, b). To protect the microstructure during polishing, the samples are often impregnated with resin. The process is comparable to the preparation of SEM-BSE samples as introduced in the previous section. The epoxy used should have very low viscosity such that it impregnates into the fine porous structure of cement-based materials. The heat release from the resin hardening should also be low to minimize thermal expansion damage to the microstructure. Figure 12a displays an example of a polished cross section of an ASR production vein125. The heat map is the concentration of K (potassium) measured by the XRF detector in the micro-XAS beamline. In comparison with SEM images of the same area, a region with high K content (red color) has a crystalline feature, while the region with low K content (green color) has an amorphous feature. The focused beam measures the Ca K-edge XAS of multiple points inside each region. The distinct peak features suggest different molecular structures.

a Polished surface125, b thin section118, c drop cast of powders115, and d thin rod/cuboid26,131.

When the detector and beam source are on the same side of the sample, the recorded signal is reflective of the incident beam, hence the thickness of the sample is not critical. Whereas when detector and incident beam are on opposite sides, the sample needs to be sufficiently thin to allow the transmission of x-ray (Fig. 12b). The required thickness is typically in the range of 100–101 µm, and thinner when the incident beam energy is lower. The transmission makes sample preparation more difficult but usually benefits the spatial resolution, as the incident beam interacts with a smaller volume of solid in transmission compared to reflection mode126.

An example of a thin section sample is given in Fig. 12b118. It was extracted from aged concrete, impregnated with resin, and mounted to a handling tool for polishing. When polished to ~80 µm thick, the thin section was dismounted from the handle by dissolving the glue between them using a special solvent. The thin section was then placed on the sample stage of a micro-XRD beamline in the Spring-8 synchrotron facility. The incident beam was focused to scan the area of interest on the thin section, yielding Debye-Scherrer rings on a plate detector. Integration of the rings will yield normal x-ray diffractogram that allows qualitative/quantitative analysis of the crystallography of the scanned area.

Drop cast is another common way to prepare powder samples for transmission measurement (Fig. 12c). Both dry127 and liquid-suspended114 powders can be dopped to a thin substrate that are transparent to x-ray, such as a silicon nitrite window. This is useful in studying particles undergoing reactions, such as hydration128, carbonation129, and convention115, since the alternation to particle morphology is negligible during the drop cast. This setup works for micro-XRD, micro-XAS, and imaging techniques such as ptychography.

Micro-X-CT and ptychography

A tomography scan requires the sample to always stay within the field-of-view during rotation, i.e. the sample dimensions need to be small along the planar direction perpendicular to the rotation axis (Fig. 12d). The sample should be either originally in that geometry, or carefully extracted from a solid bulk without modifying the microstructure. For example, cement paste can be cast into capillary tubes and subject to micro-X-CT scan in both fresh and hardened conditions in an in situ manner130. When coupled with SEM, a focused ion beam (FIB) enables extracting specific sub-volume of interest. The extracted cuboid can be readily tens of microns in size, suitable for micro-X-CT measurement. A micro cuboid from an ASR-damaged concrete and a micropillar from a hydrated cement are shown in Fig. 12d, both cut with FIB. They were subjected to micro-XRD scan afterwards26,131 The ASR cuboid reported26 was further subjected to an atmosphere of controlled RH, enabling the in situ observation of moisture uptake into ASR.

Ptychography scan is in transmission mode, hence sample must be sufficiently thin. Thin sections, drop cast115,128, capillary tube casting130,132,133, and FIB cutting131 are all suitable ways to prepare samples for ptychographic imaging. Ptychography data can be readily used for computed tomography. Compared with micro-X-CT, ptychographic-CT usually takes a much longer time to collect the projections (up to several hours). It is critical to ensure the samples are not affected by dehydration/carbonation during the scanning. Samples encapsulated in capillary tubes or impregnated in resin are usually stable during long-term scanning.

Applications in sustainable materials in concrete technology

The application of the above synchrotron microprobes in sustainable cement and concrete study is introduced in this section. Focus is given to micro-resolved studies, thus synchrotron powder XRD is not included here, though there is a large quantity of work in this field.

Supplementary cementitious materials

SCM has been extensively studied using conventional lab-based methods. The micro-heterogeneous and amorphous nature of SCM is hard to capture using conventional methods, yet the combined used synchrotron microprobes have provided unique insights in the property of raw SCM particles and their hydration.

The fly ash particles are known to contain multiple components with distinct chemical composition and crystallinity. The Al and Si species are crucial to its pozzolanic reactivity. Li et al. used ptychographic imaging coupled with micro-XAS and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to study such micro/nano heterogeneity134. As shown in Fig. 13a, the ~10 nm resolving power in transmission mode unveils the uneven distribution of matter in a fly ash particle. The micro-XAS data at Si and Al K-edge suggest three components that contain both Si and Al (Fig. 13b). The Si K-edge of SiO4 tetrahedra connected with four-fold coordinated Al (AlIV) is higher than SiO4 tetrahedra sharing oxygen with six-fold coordinated Al (AlVI). Through spectrum comparison with reference minerals, it was found that AlIV exists in homogeneous mullite particles (red particle in Fig. 13c), while disordered AlIV and AlVI may co-exist in some particles (green and blue, respectively, in Fig. 13c). Hu et al. combined micro-X-CT with nano X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to investigate the 3D chemical heterogeneity of a fly ash particle135 (Fig. 13c). Element distributions were rendered with the 3D structure, suggesting that soluble elements such as Ca and K are more on the surface and may contribute to early hydration, while Fe is inside the particle may have negligible influence on the hydration system.

a Ptychographic imaging of fly ash particles and c the heterogeneous distribution of different Al species based on b the K-edge XAS features of Al and Si134; micro-X-CT results of d a fly ash particle (with Au ball marker attached)135, e a hydrated OPC-silica fume-volcanic ash paste136, and f an LC3 paste at various ages137.

Micro-CT was also reported to study the microstructure of hardened OPC paste containing silica fume + volcanic ash136 (Fig. 13e). The resolved 3D pore structure suggests that substituting OPC with these SCMs helps refine the pore space. The benefit effect is maximized at 10% silica fume + 10% volcanic ash substitution, and vanishes when volcanic ash is above 50%. This finding guides the environmentally friendly usage of volcanic ash disposals. A similar micro-CT work was reported for OPC paste containing limestone + calcined clay137 (Fig. 13f). Four components were resolved by the phase-contrasting mode at 10−1–100 µm resolution: porosity, hydrates, unhydrated cement and calcite. It provides direct evidence that the calcite particles has reacted from 28 to 60 days, accompanied by a significant drop of pore connectivity. The finding adds novel knowledge to the hotly studied LC3 cement.

Other low-carbon approaches

Strength-boosting admixture may reduce the demand for cement in the mix design, hence reducing the embodied carbon in concrete. Li et al. studied the influence of C-S-H138. Quantified analysis of the 3D images suggests that C-S-H seeding increases the hydration product by 10–15% in the first few hours of hydration, hence densifies the pore structure (Fig. 14a). This effect is more pronounced when the Ca/Si ratio of the seed is lower. Artioli et al. monitored the hydration of OPC with and without PCE using micro-X-CT139. Radial distribution functions were calculated between the unhydrated cement and the hydration products at 7 days of hydration. A much better spatial correlation is observed between them in the absence of PCE, suggesting that the hydration product tends to nucleate and grow on cement surfaces when PCE is not used. In the presence of PCE, hydration products tend to nucleate and grow in the solution.

a Hardened paste modified by C-S-H seeding138; b fly ash geopolymer in comparison with c mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) date140; d ITZ of recycled aggregated149; e Roman concrete from relics of Pompei141.

Geopolymer has been extensively studied as a low-carbon binder in the past decades. Das et al. used micro-X-CT to study the microstructure of alkali-activated fly ash (AAFA)140 (Fig. 14b, c). In the activated AAFA paste, 10–20 μm pores contribute the most to the total porosity. Permeability can be reasonably predicted from 3D images, while tortuosity is found to be a critical factor to permeability and may drastically change in the later age of hydration.

Recycling aggregates from demolished concrete is an important pathway towards sustainable concreting. The interface between recycled aggregate (RA) and new cement matrix is usually a weak zone both in mechanical and transport behavior. Leite and Monteiro studied such interface in concrete containing RA from different sources and in distinct initial moisture conditions (Fig. 14d). Micro-X-CT data reveals the release of air bubbles at the interface when RA is initially dry, whereas the ITZ is much denser when RA is in saturated-surface-dry (SSD) condition. A pronounced portion of large bubbles (equivalent diameter >100 µm) is found in ITZ near dry RA, whereas the ITZ near SSD RA contains mainly 20–40 µm bubbles. Ancient Roman concrete was also studied by the same team141 (Fig. 14e). A cuboid sample collected from Pompei relics was scanned by micro-X-CT to study its permeability. Compared to OPC concrete, the studied Roman concrete sample has relatively high porosity, low connectivity, and similar water permeability. A novel improvement reported in this study is the usage of a machine learning (ML) algorithm to segment the pores, aggregates, and paste matrix142. This has been challenging since a global gray value threshold between low-density hydrate products and porosity is hard to determine. The applied ML algorithm conducts segmentation based on multiple features alongside the gray value.

Long-term behavior

Many papers were published to explore the interaction of heavy metals in cementitious materials, by researchers who study concrete as a shielding material for underground repository of radioactive waste133,134,135. A review can be found in ref. 143. The methodology is consistent, i.e., soluble forms of metal elements were added to cement paste, which were subjected to storge for an extended period. Combined synchrotron microprobes, such as micro-XAS and micro-XRF, are used to detect the micro-concentrating of the elements and to understand their local chemical environment. An example is given in Fig. 15a, where Co speciation was found to largely depend on the availability of oxygen. The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS, a unique type of XAS) data collected from micro-XAS setup was Fourier transformed to radial structure function (Fig. 15b), where the peak positions correspond to the distance between the center atom (Co) with the atoms shells surrounding it. By comparing with the measured data of reference phases with known structure (e.g., Co(III)-asbolane, Co(III)-buserite, Co(III)OOH, and Co(II)OH in Fig. 15b), the chemical condition of the measured Co area can be interpreted. In the absence of oxygen Co(II) mainly exists in a Co-hydroxide-like phase, while in the presence of oxygen Co(III) is more dominant and tends to be incorporated into a CoOOH-like phase.

a Speciation of cobalt (Co) in hardened cement paste and b Phase assignment by comparing the radial structure functions obtained from micro-XAS213; c Micro-XRD of the vicinity of rebar undergoing corrosion and d the Fe speciation from quantitative XRD analysis144; e 3D distribution of various alkali-silica-reaction products from tomographic micro-XRD scan26.

Micro-XRD is also used to study the corrosion process of iron in concrete, e.g. the rebar144 or iron particles from GGBS145. In the example in Fig. 15c, a rebar embedded in concrete underwent fast corrosion via accelerated ingress of chloride. The cross section was subject to micro-XRD scanning at a spatial resolution of 101 um. The obtained 2D diffraction pattern of each scanned pixel (Fig. 15d) was integrated into the diffractogram and analyzed to yield the quantify of the crystalline component, e.g., green rust, akageneite, goethite, and iron. The finding suggests a 1 mm spreading distance of iron (hydr)oxide in the binder after 44 h of corrosion. The initially formed green rust that contains Fe(II) and Fe(III) tends to become ferric oxyhydroxides during the spreading. The different corrosion behavior of stainless steel was reported by another micro-XRD study, suggesting that goethite and akaganeite are the main (hydr)oxide product of stainless steel in concrete containing chloride146,147,148. Goethite forms closer to the surface of the steel where Cr is richer, whereas akageneite forms at a distance where Cl is rich. A combined micro-XRD and micro-XAS study of aged GGBS concrete shows that the particular Fe(0) was no longer visible in a seawater condition, proving the micro-accelerated corrosion in Cl-rich environment145.

ASR is a threat to concrete containing alkali and reactive silica. A lot is unknown about the expansive ASR product as it resides in small cracks inside concrete. Geng et al.115 used micro-XRD in tomographic model and obtained 3D data of the diffractogram of a product vein, under in situ varied RH condition (Fig. 15e). Two ASR products with similar layered structure but distinct water-absorbing behavior were identified. The long-accepted theory that ASR product swells when in contact with moisture was challenged as the in situ CT scans revealed no volume change of the product agglomerates when the product absorbed water.

Bossa140 and Tan149 used micro-CT to monitor the concrete microstructure change during water leaching. The high resolution and non-destructive approach allow a direct comparison at 10−2–101 µm scale140. The size and the connectivity of the pore structure were quantified from the 3D images. Using random walk simulation, the diffusion coefficient of were revealed to increase by 50 and 100 times higher when leaching at 20 and 80 °C occurred, respectively. The Ca(OH)2 dissolution is faster when the aggregate is close to the dissolution front, likely due to the presence of ITZ on the aggregate surface149.

Strength and limitations

Synchrotron radiation facilities offer a set of micro-resolved probes. Attributing to the high brightness and tunable energy, these probes often come with high resolution in both space and time, making them powerful tools for studying systems that evolve rapidly and/or with high spatial heterogeneity. Without the need for a vacuum condition, synchrotron probes can be in situ for hydrated systems, which is impossible for electron microscopies. The element-sensitive methods such as micro-XAS allow tracking the speciation of elements-of-interest, providing valuable information to understand the fate of heavy metals in wastes when using them in concrete. These are all advantages of synchrotron-based methods over conventional laboratory methods.

Meanwhile, synchrotron probes obviously are not easily accessible. The application-approval-experiment cycle can be as long as a year. One must have sufficient understanding of the samples using conventional probes, and use synchrotron probes primarily for problems that can only be solved by these unique methods. The researchers must have sufficient experience with synchrotron facilities, since there are not too many chances for try-and-error. Last but not least, traveling to a synchrotron facility can be costly, especially when it is overseas.

Micro- and nanoscale mechanical testing methods

Principles of application

Atomic force microscopy (AFM), nanoindentation, and nano scratch are the predominant methods for examining the mechanical characteristics of cementitious materials on a micro or nanoscale. These techniques enable researchers to investigate the micro/nanostructure and mechanical properties of materials. They facilitate the measurement of mechanical properties like elastic modulus, hardness, and fracture toughness at the nano-sized regions of tested materials. AFM can generate force-distance curves when in contact with the sample surface, offering valuable insights into stiffness and adhesion force150. The nanoindentation technique was pioneered by Nix in 1986151 and subsequently by Pharr in 1992152. Initially employed for the examination of homogeneous materials, it has since found broad application in the analysis of heterogeneous materials, such as cement-based materials. Nano scratch has gained growing popularity as a technique for nanoscale assessment and profiling of thin films, coatings, and bulk materials. This method is invaluable for evaluating adhesion strength, scratch hardness, wear resistance, fracture strength properties153,154, fracture toughness155, and interface bond strength156,157 across a diverse range of materials. The coefficient of friction can be determined by the ratio of lateral force to normal force between the indenter and the test material. These parameters effectively capture the nano-tribological behavior exhibited by the materials under examination.

In terms of testing principles, ref. 158 have noted that there is no substantial distinction between AFM indentation and traditional nanoindentation. Despite the shared objective of extracting mechanical information, their operational methodologies differ significantly.

AFM

Figure 16 depicts a schematic representation of a typical AFM utilizing a laser beam deflection system. This AFM system comprises essential components, including a probe (a microcantilever with a sharp tip), a focused laser beam, and a photodetector. Additionally, a scanner and a feedback loop are integral parts of the setup. The fundamental concept behind AFM design is to measure the atomic forces at play between the probe and the test sample159. When the distance between the sharp tip and the sample reaches critical proximity, the interatomic interactions become significant, allowing the sensitive cantilever to detect minute variations in these forces. The curve depicting the relationship between force and tip-sample separation during a single-cycle AFM test is shown in Fig. 16.

The tests include nanoindentation, nanoscratch, and AFM test.

Taking the example of the contact mode, during the testing process, the flexible cantilever undergoes deflection as the relative distance between the sharp tip and the sample changes while scanning. The cantilever’s deflection is continuously fed into a feedback loop, which in turn adjusts the height of the probe support to maintain a constant cantilever deflection. This procedure allows for the acquisition of force signals through the feedback output.

Nanoindentation

The nanoindentation testing process is relatively straightforward. In a nanoindentation test, a known indenter with specific geometric and mechanical attributes is progressively pressed into the test material as the applied load steadily increases until it reaches a predefined threshold. Subsequently, the load is held constant for a period to mitigate creep effects and then gradually withdrawn. Throughout the test, the applied load (P) and the depth (h) to which the indenter penetrates are meticulously recorded.

Nanoindentation offers more advanced capabilities, including grid nanoindentation analysis. In this approach, an extensive grid is superimposed onto a designated area of interest within a material, with nanoindentation tests performed at each grid point. Through the integration of statistical analysis, the mechanical properties of individual phases are deduced. The application of the Statistical Nanoindentation Technique (SNT) has yielded a wealth of research findings and theories160. Building on this foundation, more advanced data acquisition methods, such as modulus mapping, have been introduced to expedite scanning and gather additional data.

Nano scratch

In contrast, nano scratch serves a different purpose. Rather than providing detailed point-by-point information on material modulus and hardness, nano scratch is employed to investigate the continuous region of material, specifically focusing on the study of nano-tribological behaviors161.

In a nano scratch test, an indenter is first applied to the specimen by exerting force upon it (Fig. 16). Subsequently, the indenter is drawn in a straight line across the surface of the tested specimen at a predefined velocity. The nano scratch testing system comprises two transducers: one for monitoring the control force (normal force) and displacement in the pressing direction, and the other for recording the force (lateral force) and displacement in the direction of movement162. Additionally, it is customary to perform a pre scratch scan and a post scratch scan with minimal load in conjunction with the nano scratch test. These scans serve to establish the initial surface topography and determine the residual scratch depth163,164. The penetration depth values can be computed by subtracting the data from the pre scratch scan from that of the scratch test itself.

Nano scratch testing encompasses several modes, including constant load nano scratch tests, ramped load nano scratch tests, and multi-pass repetitive unidirectional constant load nano scratch tests, commonly referred to as “nanowear”161. The distinguishing feature of nano scratch testing is the continuous monitoring of mechanical parameters throughout the test. Consequently, it is anticipated that this method will yield a more extensive dataset in the specified test area compared to other discrete point measurement techniques.