A systematic analysis of disability inclusion in domestic climate policies

Introduction

Multiple decisions adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC, including in the preamble to the Paris Agreement, and several resolutions of the UN Human Rights Council have recognized the importance of including people with disabilities and their rights in the world’s response to the climate crisis1. Although the scholarship in this area is still sparse2,3,4, a growing body of evidence suggests that people with disabilities experience disproportionate rates of mortality and harm in both extreme weather events and slow-onset gradual impacts fueled by climate change1,5,6,7,8. The heightened climate vulnerability of people with disabilities is primarily due to their exclusion from disaster risk readiness and adaptation responses9,10,11,12,13 and underlying patterns of social, economic, and institutional marginalization that increase their exposure and sensitivity to climate impacts and undermine their adaptive capacity1,14,15,16. These risks are even greater for people with disabilities affected by intersecting forms of discrimination and marginalization tied to their race, Indigeneity, sex, age, gender, sexual orientation, class, and caste17,18.

Moreover, a burgeoning literature on the linkages between disability inclusion and environmental justice19,20,21,22 has also demonstrated that climate policies often fail to take into account the perspective and rights of diverse members of disability communities worldwide1,23. For example, measures designed to limit the use of automobiles that run on fossil fuels through carbon pricing schemes and restrictions on city parking have frequently been adopted without full consideration of the differentiated needs of citizens with mobility impairments or the physical and financial accessibility of low-carbon alternatives (such as mass transit or cycling)24. Climate policies that are based upon a universal conception of able-bodiedness only reinforce the inequities encountered by people with disabilities in society25. They also reduce the share of the population that could contribute to and benefit from the emergence of low-carbon societies19,26, including the estimated 15% share of the world’s population that has a disability27 as well as the growing number of older adults in developed countries28.

Despite the important implications of climate change and climate action for people with disabilities, little is known about whether, how, and why they have been included in domestic climate policymaking5,11. Using the methodology developed by Lesnikowski et al.29, we address this gap by systematically analyzing two sets of policies adopted by the 195 parties to the Paris Agreement: their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) or intended NDCs (INDCs) and their framework climate adaptation policies. In all, we collected and coded 546 NDCs/INDCs and 317 adaptation policies and built an original dataset of climate policies that refer to disability (44 INDCs/NDCs and 88 adaptation policies; see supplementary material 1 for the complete dataset).

Our analysis is based on the “human rights model of disability,”30,31 which is enshrined in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD)32, an international treaty that has been ratified by 191 parties (190 states and the European Union), including all, but four of the 195 parties to the Paris Agreement (namely Niue, South Sudan, The Holy See, and The United States)33. This approach emphasizes the obligation of governments to respect, protect, and fulfill the human rights of people with disabilities and ensure their formal and substantive equality in the development, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of climate policies1,11,15. Under the UNCRPD, this encompasses civil and political rights (such as the rights to life and to protection in situations of risk); economic, social, and cultural rights (such as the rights to health or an adequate standard of living); and rights that address the unique requirements of persons with disabilities (such as rights to accessibility, independent living and inclusion in the community, and personal mobility)1,15.

A disability rights framework has three main implications for developing and implementing climate policies (see Table 1 below). First, states must respect, protect, and fulfill the human rights of people with disabilities in the context of climate action. Respecting disability rights entails that states ensure that their climate policies do not violate the rights of people with disabilities; protecting these rights requires that states prevent third parties from violating them in the context of climate change or climate action; and fulfilling these rights means that states must take steps to fully realize these rights by leveraging their climate policies to address existing barriers in society34. Second, states must assess and address the differential effects of climate change for persons with disabilities, taking into account how their impairments and the barriers they face in society generate and exacerbate their vulnerability to different types of climate impacts and risks15. This exercise must also be conducted through an intersectional approach that recognizes the effects of multiple and compounding forms of discrimination based on gender, disability, ethnicity, age, and poverty4,11,17. Finally, states must ensure the full and effective participation of people with disabilities in climate decision-making, action, and justice1,12,15. This entails providing them with access to information, capacity-building, and resources to support and empower them as agents in climate governance35, meaningfully involving them and their knowledge in the development, implementation, and evaluation of climate policies and programs2,4, and ensuring they have access to judicial and administrative remedies when they experience harm due to climate change or measures adopted to combat it34,36.

Results

The inclusion of people with disabilities and their rights in NDCs

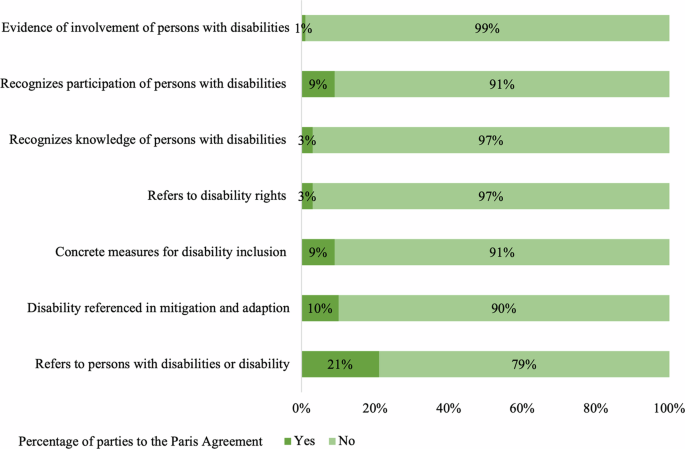

Our analysis demonstrates that only 41 of 195 parties to the Paris Agreement currently refer to persons with disabilities or disability in their active NDCs. This means that 79% of parties currently do not refer to disability in any way in their NDCs (see Fig. 1). A closer look at how people with disabilities are included in these 41 NDCs reveals that many of these references are broad in nature and lack specificity and depth. Most NDCs simply note the heightened vulnerability of people with disabilities to climate impacts37,38,39. Some countries, such as the Maldives or Vietnam, go a little further than others in mentioning concrete manifestations of the climate vulnerability of people with disabilities, such as children with disabilities dropping out of school because of the disruptions to healthcare facilities caused by climate impacts40,41. Other NDCs merely identify people with disabilities as a segment of the population requiring specific adaptation initiatives, without elaborating on what these might entail or how they should be developed and implemented42,43.

Disability inclusion in nationally determined contributions.

We found that only 17 parties include concrete measures for disability inclusion in their NDCs. For example, several countries note the need for disaggregated data collection concerning the impacts of climate change and disasters on marginalized groups, including persons with disabilities44,45. Other countries propose the inclusion of people with disabilities in the transition to a low-carbon economy through initiatives such as equitable access to green jobs (Canada)46 or creating virtual working environments (Jordan)47. Some states are innovative in their approaches. Tunisia highlights the need for solidarity amongst people with disabilities through networks that reinforce their negotiating power48. Georgia and Saint Lucia emphasize the importance of educational programs for people with disabilities49,50. Finally, Costa Rica includes a very specific commitment: the development of a public transportation system that is fully accessible to people with disabilities51.

We found that Vanuatu has the most robust NDC in terms of disability inclusion52. It is the only NDC that includes “people with disabilities” as a heading of their submission, with three separate priority areas focused on disability concerns, complete with specific monetary values to achieve these targeted measures. Vanuatu’s NDC includes commitments to provide people with disabilities with information necessary to address the health risks of climate change; promote the participation of people with disabilities in adaptation planning; and provide support and resources to persons with disabilities initiating and running adaptation projects.

Only six NDCs specifically refer to the rights of people with disabilities and only five recognize the importance of integrating their knowledge in climate decision-making. While 18 NDCs recognize the importance of ensuring the participation of people with disabilities, only the NDCs submitted by Cambodia45 and the Republic of Congo53 provide any evidence that people with disabilities were involved in their development.

The inclusion of people with disabilities and their rights in climate adaptation policies

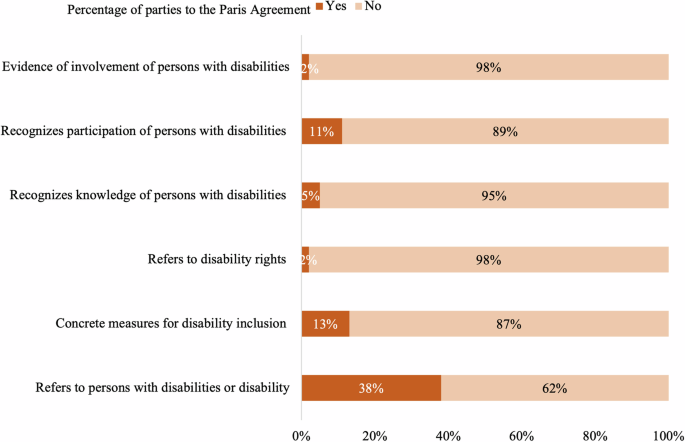

Our analysis reveals that only 75 of 195 parties to the Paris Agreement currently refer to people with disabilities or disability in some way in their framework climate adaptation policies. Approximately 61.5% of states do not mention disability in their adaptation plans at all.

Moreover, references to disability in domestic climate adaptation policies remain cursory in nature (see Fig. 2 above). The US Adaptation Strategy54, for instance, merely includes people with disabilities in a list of groups that face disproportionate impacts from climate change. Only 26 adaptation policies include concrete measures to ensure that persons with disabilities and their priorities are included in adaptation decision-making and initiatives. Canada’s Adaptation Action Plan proposes several potential opportunities for disability-inclusive climate action, including the purposeful design of infrastructure programs that promote accessibility and the adoption of early-warning systems that meet the needs of persons with disabilities55. Bhutan’s 2023 National Adaptation Plan includes commitments to improving and building water, sanitation and hygiene infrastructures that are accessible to persons with disabilities56. Another example is Kiribati’s 2019 Joint Implementation Plan for Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management, which includes plans to develop and implement plans to provide information regarding climate risks and their impacts on health targeted to people with disabilities and provided in a manner that is inclusive and addresses “known barriers for communication for key population groups.”57.

Disability inclusion in adaptation policies.

Only 21 States refer to the participation of persons with disabilities in their climate adaptation policies. Pakistan’s 2023 National Adaptation Plan includes a commitment to prioritize “the participation of marginalized groups, in particular women, children, indigenous groups, and persons with disabilities, in decision-making to ensure that their needs, knowledge, and perspectives are taken into account.”58. Many policies describe concrete measures to ensure the participation of persons with disabilities in climate adaptation efforts through capacity building (see, for example, the policies of Uruguay and Turkey)59,60 or by directly involving them in the development of climate adaptation policies (see, for example, the policies of Mexico and Kiribati)57,61. Several states, such as Ghana and Madagascar, also indicate that they will provide support for disability-led climate adaptation efforts62,63.

The limited recognition of the importance of including persons with disabilities in adaptation planning, along with the even smaller number of policies that recognize the value of their knowledge (9) or provide evidence that were involved in any way in policy development (4), shows that the disability community continues to be systematically excluded from domestic adaptation policymaking.

Assessing overall levels of disability-inclusive climate policymaking

To provide an overall assessment of a party’s commitment to disability-inclusive climate action, we transformed our qualitative legal analysis results into a numerical value. Each NDC was assigned a disability inclusion score based on 7 criteria and each adaptation policy was assigned a score based on 6 criteria (see Methods). We added the scores assigned to INDCs/NDCs and climate adaptation policies to provide a global score of disability-inclusive climate policymaking for each party to the Paris Agreement (see Supplementary Material 2). The average score in our global assessment is a paltry 1.1 out of 13. Although their policies are not fully aligned with their obligations under the UNCRPD, Canada, Costa Rica, Sierra Leone, Cabo Verde, and Kiribati stand out among their peers as countries that have the highest levels of disability inclusion across the two sets of climate policies we analyzed (see Table 2). At the other end of the ranking, 97 parties to the Paris Agreement achieve a global score of 0, which means that neither their NDCs, nor their adaptation policies include even a single reference to persons with disabilities. Finally, 73 countries refer to persons with disabilities in either their NDC or adaptation policy but do so without including any concrete measures for disability-inclusive climate decision-making and action.

Discussion

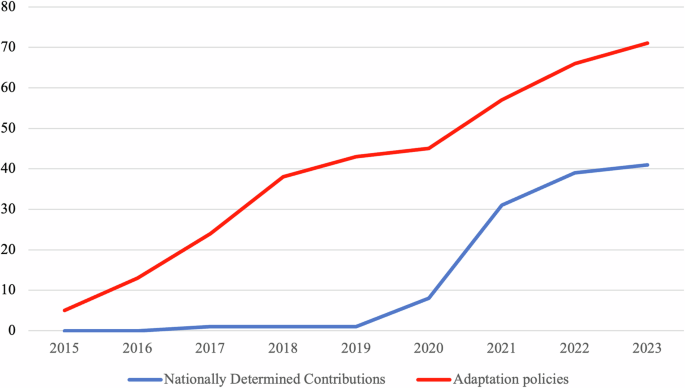

Our systematic analysis yields four key findings. First, disability is slowly emerging as a consideration for climate governance, although there are significant variations in whether and how it is effectively treated by policymakers. Since 2015, references to disability have gradually increased in both sets of policies analyzed in our study (see Fig. 3).

Cumulative references to disability in climate policies over time.

At the same time, our results also show that people with disabilities have received more attention in adaptation planning than in the overall climate plans and commitments of states. We found that 38.4% of adaptation policies include at least one reference to disability, while only 21% of NDCs do so. A closer look at the context in which people with disabilities are referenced in NDCs reveals that 36.5% of these references relate to climate adaptation, while only 14.6% pertain to climate mitigation. 48.78% of NDCs include references to disability that pertain to both adaptation and mitigation.

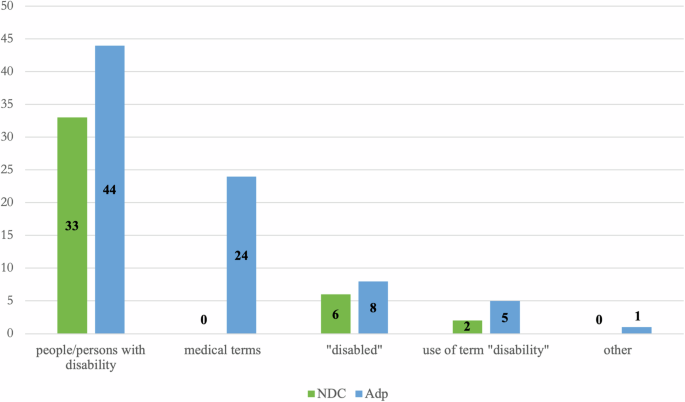

These lopsided results suggest that while climate policymakers are beginning to pay attention to the climate vulnerability of people with disabilities, they continue to disregard the disability-related implications of reducing their carbon emissions2. The predominance of a vulnerability framing of people with disabilities is also evident when we consider the language used to refer to them in climate policies (Fig. 4). Indeed, 24 adaptation policies use medical terminology (such as people with chronic illnesses) rather than employ the terms persons or people with disabilities. This medical conception of disability has long been criticized by disability activists and scholars because it focuses on impairments that differ from a normative ideal of health and suggests that individual medical interventions, rather than broader forms of political, legal, and social change, are needed to overcome the marginalization faced by persons with disabilities64. To fully align their climate policies with the human rights model of disability, states must move beyond a predominant focus on the vulnerability of people with disabilities and embrace their potential contributions as agents whose lived experience and relationships can enhance the effectiveness and equity of climate governance4,35.

Predominant framing of Disability in Nationally Determined (NDCs) contributions and Adaptation Policies (Adps) by country.

Second, our findings speak to the larger challenge of ensuring that efforts to combat climate change meaningfully include members of equity-seeking groups and center their agency, rights, and knowledge. Our results suggest that references to people with disabilities in climate policies lag behind those to women and Indigenous Peoples, who have gained increasing recognition in NDCs65,66 as well as adaptation policies29. At the same time, the concrete implications of the emerging practice of including references to women and Indigenous Peoples in climate policies should not be overstated either. As is the case for persons with disabilities, mentions of these groups in climate policies tend to lack substance, and all three groups continue to face significant barriers to their full and effective participation and the adoption of differentiated climate policies65,67,68. Efforts to mainstream the rights of equity-seeking groups in climate governance must be aligned with one another through an intersectional approach that recognizes the intersecting as well as distinct challenges and opportunities faced by each group17,18,69.

A third key finding of our analysis is that developing countries and emerging economies from the global south appear to outperform industrialized countries from the global north. Lower middle-income countries perform slightly better in our global assessment of disability-inclusive climate policy-making than those from other income groups (see Table 3). In general, industrialized countries from the global north perform worse than one might expect given their resources and older populations (with resulting higher rates of disability). Yet, Canada is the only industrialized global-north country that features in the top twenty-five in our global ranking (see Supplementary Material 2). It is confounding that countries with strong records of supporting and implementing disability rights in other spheres of public policy are failing to abide by their obligations under the UNCRPD. Further research is needed to understand why climate policymakers continue to overlook the disability community and to identify best practices for overcoming barriers to disability-inclusive climate action around the world.

Finally, we report here that most parties to the Paris Agreement are failing to comply with the obligations they owe persons with disabilities under international human rights law in the development and implementation of their climate policies. 94 parties to the Paris Agreement continue to completely neglect people with disabilities in their climate policymaking altogether and 76 parties refer to them in a cursory manner without specifying at least one concrete measure for disability-inclusive climate action. While a small number of parties are beginning to take significant steps to include people with disabilities in their climate decision-making and planning, the average score achieved by parties with a score of 1 or more in our global assessment is only 2.8 out of 13. This overall lack of disability-inclusive policymaking is not unique to climate governance. Scholars have noted time and time again that efforts to realize disability rights tend to be confined to disability-focused regimes and policies and are neglected in other fields of public policy70,71,72.

Overall, we find that states are systematically breaching their obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill the human rights of persons with disabilities under international law (as well as, in most cases, domestic constitutional and human rights law). Two violations of the articles of the UNCRPD are worth highlighting here. The complete lack of any references to people with disabilities in 108 adaptation policies and the omission of concrete measures to ensure their inclusion in 167 policies is glaringly inconsistent with Article 11 of the UNCRPD. This provision obliges states to “take all necessary measures to ensure the protection and safety of persons with disabilities in situations of risk,” including the types of emergencies and natural disasters fueled by climate change15. Although they have recognized the heightened climate vulnerability of persons with disabilities in the UNFCCC and UN Human Rights Council, states are failing to enhance their capacity to cope with the impacts of climate change on their lives, safety, and human rights, thereby exposing them to disparate rates of mortality and harm due to climate change14,73.

Moreover, the systematic neglect of the rights, participation, and knowledge of people with disabilities in the development and implementation of NDCs and adaptation policies clearly infringes Article 4 of the UNCRPD. This provision specifies that states shall “take into account the protection and promotion of the human rights of persons with disabilities in all policies and programs,” and “closely consult with and actively involve persons with disabilities” in decision-making processes that concern them. The ongoing failure of states to ensure the full and effective participation of people with disabilities in climate governance undermines their claims to equality and citizenship19,20 and reinforces the barriers they face in society1,25. It also reduces their ability to contribute their leadership, knowledge, and unique strengths to efforts to make societies more sustainable19,24,26 and enhance their resilience in the face of the climate crisis35. Finally, this exclusion is a missed opportunity since disability-inclusive climate solutions can be leveraged to dismantle the barriers faced by people with disabilities as well as generate “resonant impacts” that increase the accessibility of climate action to a wide variety of individuals with different abilities, needs, and preferences1,15.

Methods

Data collection

We collected two types of documents to complete this systematic analysis. First, we retrieved all the INDCs and NDCs submitted by a party to the Paris Agreement and filed with the UNFCCC Secretariat from January 1st, 2015 to December 31st, 2023. A total of 546 INDCs/NDCs were collected. Second, we systematically collected the framework climate adaptation policies adopted by parties to the Paris Agreement. We examined the national communications submitted by state parties from January 1st, 2015 to December 31st, 2023. We extracted the titles of the most recent framework climate adaptation policies from these communications and searched online to retrieve them. We excluded 10 of these documents following unsuccessful attempts to retrieve them online. We also downloaded and analyzed the National Adaptation Plans submitted by parties to the UNFCCC Secretariat (and available on its website as of December 31, 2023). A total of 317 framework adaptation policies were collected. Finally, we reviewed these policies and retained those that include at least one reference to disability. Our final dataset includes 44 INDCs/NDCs and 88 adaptation policies (see supplementary material 1).

Data coding

The policy coding protocol was designed based on a series of questions about the extent to which key elements of a disability rights approach to domestic climate governance are represented in climate policies. The results reported in this article typically refer to the most recent policy that is in force for each country. If there were multiple climate policies that were still in force, we calculated an average score across all policies. Each policy was independently coded by two coders in the original language of the document, considering any differences in the social, cultural, or legal terms used in different countries to refer to disability, including people and persons with disabilities, the disabled, and other equivalent terms (such as references to chronic illnesses or health conditions). Disagreements in coding were resolved through discussion with the coders and the principal investigator.

|

Disability inclusion criteria and scoring for climate policies |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Criterion |

Scoring |

Policies Scored |

|

Does the policy refer to persons with disabilities or disability in one way or another? |

1 = use of the term people/persons with disabilities or disabled people; 0.5 = medical terms/framing and use of term disability; 0 = if no reference. |

NDCs and adaptation policies |

|

Is the reference to disability included within the context of climate mitigation, adaptation or both? |

1 = adaptation and mitigation; 0 = adaptation or mitigation only. |

NDCs only |

|

Does the policy include at least one concrete measure for enhancing disability inclusion in climate action? |

1 = yes; 0 = no. |

NDCs and adaptation policies |

|

Does the policy refer to the rights of persons with disabilities? |

1 = yes; 0 = no. |

NDCs and adaptation policies |

|

Does the policy recognize the importance of integrating the knowledge held by persons with disabilities? |

1 = yes; 0 = no. |

NDCs and adaptation policies |

|

Does the policy recognize the importance of the full and effective participation of people with disabilities in climate governance? |

1 = yes; 0 = no. |

NDCs and adaptation policies |

|

Does the policy include evidence that people with disabilities were involved in its development? |

1 = included; 0.5 = consulted; 0 = no evidence. |

NDCs and adaptation policies |

Responses