A systematic review of digital and imaging technologies for measuring fatigue in immune mediated inflammatory diseases

Introduction

Fatigue is a highly prevalent and disabling symptom in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)1,2. In chronic diseases, fatigue is generally considered to be a “persistent, overwhelming sense of tiredness, weakness or exhaustion resulting in a decreased capacity for physical and/or mental work and is typically unrelieved by adequate sleep or rest”3. It negatively impacts patient quality of life both during active disease and in remission. A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis estimated the global prevalence of fatigue in IBD to be 72% during active disease and 47% during remission1. In the workplace, fatigue in IMID is associated with absenteeism, presenteeism, and general activity impairment4. An 8-year-long longitudinal study of 626 RA patients found that despite improved treatment strategies, fatigue severity remains unchanged3. From the patient perspective, fatigue is one of the most important symptoms to track and monitor5,6. Fatigue is a significant concern in IMID because of its high prevalence, persistence during active disease and remission, and significant negative impact on patient quality of life. Despite its prevalence, the etiology of fatigue is not fully understood in these chronic diseases7.

Currently, fatigue is primarily measured through patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in the form of questionnaires conducted in the clinic or through electronic platforms (ePRO). PROs highlight the patient perspective and experience, which is highly relevant and important to the patients during treatment; however, new and emerging methods could potentially complement PROs with continuous, objective, and quantitative measurements to enable a more comprehensive assessment and monitoring of patients’ progress during treatment both at home and in the clinic8. In the past decades, there has been immense innovation and development of digital health technologies (DHTs), such as wrist-worn wearables for monitoring patients and generating novel digital endpoints9. Wearable and imaging technologies present potential opportunities to establish objective, quantitative measures of fatigue and to further our understanding of its biological mechanism. The aims of this systematic review were to: (1) explore how digital and imaging technologies have been used to measure fatigue in IMID populations and (2) determine if significant associations have been found between fatigue and digital biomarkers.

Results

Study identification and characteristics

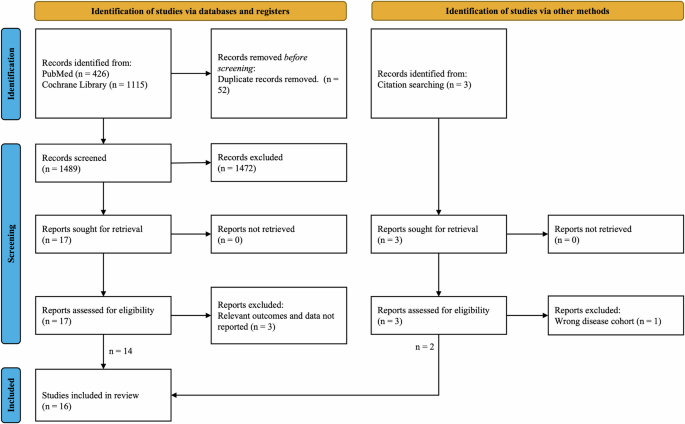

The study identification process is summarized in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Fig. 1). The PubMed and Cochrane Library database search yielded 1541 studies. A total of 17 studies were retrieved for full-text review after title and abstract screening. In total, 14 were selected for inclusion in the systematic review. Through citation searching and other sources, two additional studies were identified and included. A total of 16 references were included in this systematic review: 13 were completed studies10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, and the remaining 3 were protocols23,24,25 of ongoing clinical trials. Among the 13 completed studies publications, there were 12 unique clinical studies represented. The papers by Antikainen et al.10 and Chen et al.11 reported two different arms of the same clinical trial registered with the German Clinical Trial Registry (DRKS00021693) and were conducted as part of the IDEA-FAST project.

Overall, 1541 records were screened, and 16 studies were included in the review after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The screening process involved assessing titles and abstracts to determine relevance, followed by a full-text review of selected articles.

Characteristics of the completed studies are summarized in Table 1. The distribution of unique IMID patients in the completed studies is as follows: 55.0% RA, 7.5% IBD, 22.4% SLE, and 15.1% pSS. Three studies included more than one disease cohort, whereas all other studies included only one disease population. The sample sizes of these studies ranged from 13 to 526. The majority of the studies (61.5%) had a sample size <60. The average age of study participants varied from 30.1 to 64.6 years old. All completed studies had <50% male participants. The average disease duration ranged from 4.2 to 16.7 years. Two studies, Cheung et al.13 and van Erp et al.20, included only patients with SLE who were in remission.

Digital and imaging health technology

The completed studies implemented the following digital and imaging technologies: brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (n = 8), full-body or joint MRI (n = 2), wearable sensor devices (n = 2), and sleep devices (n = 1). Brain MRI methods included standard structural MRI, functional MRI (fMRI), diffusion tensor MRI (DT-MRI), and magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI). Joint MRI consisted of unilateral wrist, metacarpophalangeal (MCP), and metatarsophalangeal (MTP) MRI. Wearable devices included the VitalPatch, Fitbit, and the DREEM headband. The VitalPatch is a single-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) sensor while the DREEM headband is an electroencephalogram (EEG) sensor. Fitbit is a wearable fitness tracker that includes different sensors, such as a gyroscope, an accelerometer, and a photoplethysmogram (PPG) sensor, that monitor physical activities, sleep quality, respiration rate, and heart rate. Sleep devices included the ZKOne, a touchless wall-mounted ultra-wideband radar sensor, and the BedSensor, a force-sensitive foil mat placed underneath the mattress.

Most of the studies included in this review utilized MRI; all three of the clinical trial protocols include the use of wearables. The clinical trials featured the following wearable devices: Fitbit Versa smartwatch, SENS motion leg sensor, Garmin Vivosmart 4 smartwatch, Fitbit Inspire smartwatch, and SenseWear Mini armband. The smartwatches employed in these studies featured both accelerometry and photoplethysmography (PPG) sensor.

Fatigue measurement

The PROs used to measure fatigue varied across studies. These included the Chalder Fatigue Scale (CFS); fatigue visual analog scale (fVAS); Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS); Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Numerical Rating Scale (BRAF-NRS); Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue (FACIT-F); Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI); IBD Fatigue Score; Likert items for physical and mental fatigue. Across studies, some PROs were conducted in the clinic whereas others were collected as ePROs via mobile applications. There was no singular PRO used across all studies. Each PRO varies in questionnaire length and characterization of fatigue. There is no gold standard definition of fatigue, so there is variation among PROs in the type of fatigue measured.

The CFS is an 11-item self-report questionnaire commonly used for fatigue rating in clinical populations as well as the general population; it aims to measure both physical and psychological fatigue26,27,28. The fVAS is a visual line on which patients indicate with a mark how fatigued they feel, from “no fatigue” to “worst possible fatigue.” It is commonly used in the clinic for many diseases including pSS and RA26,27. The FSS is a 9-item survey in which patients respond to questions on a 7-point Likert scale. It assesses fatigue intensity and functional disability. The FSS was first created for multiple sclerosis and SLE, but it is currently used to assess fatigue in a wide variety of chronic diseases29. The BRAF-NRS is a 20-item questionnaire that aims to evaluate the following categories: physical fatigue, living with fatigue, cognitive fatigue, and emotional fatigue. It was developed for the assessment of fatigue in RA30. The FACIT-F is a 13-item Likert scale questionnaire that has been validated for evaluating fatigue in RA31. The MFI is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that measures the following aspects of fatigue: general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced motivation, and reduced activity32. The IBD Fatigue Score is based on a 28-question survey designed to clinically assess IBD patients33. Across different studies, multiple PROs are used to measure fatigue which makes it difficult to generalize and compare across studies and patient population.

Study quality assessment

Overall, the studies were of good quality according to the STROBE checklist for observational studies. However, there were a few categories in which there was a greater risk of bias within the studies. Most studies had greater risk of bias in the following STROBE checklist items: did not address potential sources of bias (69%), did not explain how missing data were addressed (77%), and did not include sensitivity analyses (77%). This review contains level IV of evidence on the hierarchy of evidence, as most of the studies were well-designed case-control or cohort studies.

Associations between fatigue and imaging endpoints

The studies reported mixed findings regarding significant associations of fatigue measured using PROs with imaging endpoints. Of the eight brain MRI studies, three investigated gray matter volume (GMV)12,14,19. Basu et al. found a significant correlation between GM putamen volume and fatigue (r = 0.31, p < 0.03) in patients with RA using the BRAF-NRS for fatigue12. Hammonds et al. also found a significant positive correlation between GMV and the fVAS fatigue scale in patients with pSS14 adjusting for age, gender, disease duration, and hypertension in the multivariable model. However, Thapaliya et al. found a negative correlation between GMV and IBD fatigue score in patients with CD19.

There were two brain MRI studies that investigated white matter volume (WMV)14,19 and its association to fatigue. Hammonds et al. found significant associations between WMV and fatigue using the fVAS PRO in patients with pSS14; however, Thapaliya et al. found no association between fatigue and WMV in patients with CD19. Again, there was heterogeneity between studies; each study utilized a different fatigue PRO and was of a different disease cohort. In addition, other MRI studies focused on white matter hyperintensities (WMHs)14,15,21. WMHs appear as MRI signal abnormalities; they are associated with decreased cognitive function in aging populations34. Significant associations between WMHs and fatigue were found in patients with pSS14 and SLE21 using the fVAS as a measure of fatigue. Harboe et al. included both the fVAS and FSS in their study; however, no significant associations were found between WMHs and the FSS in an SLE population15.

In patients with CD, van Erp et al. showed that brain metabolite levels were significantly correlated to fatigue PROs using MFI and fVAS15. While the study used the total MFI score in their correlation analysis, group-wise comparisons showed significant differences in all fatigue subtypes between CD patients and the control group. Mueller et al. also showed brain metabolites were significantly correlated with fatigue measures using FSS in RA patients17. The significant association of brain metabolite levels with two different fatigue PROs might potentially reinforce brain metabolite level as a robust biomarker of fatigue. However, additional studies should be conducted to further explore the correlation between these imaging biomarkers and fatigue.

Other imaging biomarkers such as cerebral blood flow (CBF) were also found to be significantly correlated to fatigue in patients with RA18 and CD20. Raftery et al. used FACIT-F to measure fatigue in 13 RA patients18, while van Erp et al. used MFI and fVAS in 20 patients with CD20. Thapaliya et al. also found significant associations of cortical thickness with fatigue PROs19. Wiseman et al. found a significant association between mean diffusivity and fatigue in 51 patients with SLE while adjusting for age, disease duration, and steroid use21.

Cheung et al. used whole-body MRI and localized muscle spectroscopy to investigate the association between phosphocreatine (PCr) recovery halftime to fatigue using the CFS in 19 patients with SLE in a case-control study13. While patients with SLE showed significantly higher levels of fatigue compared to the control group (p < 0.0001) as well as greater PCr (p = 0.045), there was no association between physical fatigue and PCr (r = −0.28, p = 0.25).

Matthijssen et al. used MRI of the joints to investigate the association of inflammation in the wrist, MCP, and metatarsophalangeal to fatigue in 526 patients with RA using the BRAF-NRS while adjusting for age, gender, and ACPA status in patients with RA16. While higher Disease Activity Scores (DAS) were associated with fatigue at baseline (p < 0.01), there was no association between MRI inflammation and fatigue (p = 0.08). Similarly, during follow-up a decrease in DAS was associated with an improvement in fatigue (p < 0.001); however, a decrease in MRI inflammation did not show a corresponding improvement in fatigue (p = 0.96).

Associations between fatigue and digital endpoints

The use of DHT to measure disease progression and severity in IMID is an emerging area; however, currently, there are limited studies published to show the utility of DHT to measure symptoms relevant to the disease. Studies by Antikainen et al.10 and Chen et al.11 demonstrate the potential of using DHT to measure symptoms that are relevant to IMID such as sleep and fatigue. These studies focused on recruiting patients with IBD, pSS, RA, and SLE patients to evaluate the feasibility of deploying DHT in a clinical trial as well as identify robust and more sensitive endpoints that will enable better tracking of the disease severity and progression. Antikainen et al. found statistically significant correlations between digital measures, such as heart rate and parameters of heart rate variability, and physical and mental fatigue10. However, these correlations were weak (r < 0.3) after adjusting for age and gender. Additionally, their analysis revealed no significant correlations between heart rate recovery and physical or mental fatigue in IMID patients. Meanwhile, Chen et al. explored the use of digital devices such as the BedSensor (a force sensor), DREEM (an EEG headband), and ZKOne (a wireless radar wall-mounted sensor) to identify associations of these measures with mental and physical fatigue11. Using the BedSensor, there was a significant correlation (r = 0.23) between physical fatigue and variations in respiration rate among patients with pSS. In patients with SLE, a significant correlation (r = 0.352) was also observed between mental fatigue and heart rate. Furthermore, data from the ZKOne indicated a significant negative correlation between sleep quality and physical fatigue in patient with RA (r = −0.641) and IBD (r = −0.205). Analysis of the DREEM data revealed that there was a strong correlation between duration in N2 sleep and mental fatigue in RA patients.

Rao et al. collected data from 296 participants with autoimmune diseases and healthy volunteers to develop a model for predicting mental and physical fatigue using data obtained from a Fitbit and PROs22. The results indicated that incorporating digital features enhanced the model’s accuracy in predicting both physical and mental fatigue, compared to relying solely on PROs. Furthermore, exploration of features from the model revealed that resting heart rate was a significant factor in predicting both physical and mental fatigue, while the measurement of sleep quality is more predictive of physical fatigue. The inclusion of multiple data streams in this study highlighted the complexity of capturing the multidimensional nature of fatigue from subjective measures of pain and mood to objective measures of sleep and physical activity.

With the recent development of DHTs like smartwatches, there is a growing interest to use these technologies in clinical studies to capture real-world evidence and develop new and more effective endpoints to evaluate the efficacy of new treatments. Several pharmaceutical companies have expressed their intentions to develop novel endpoints for drug assessment and leveraging new technologies to engage patient and reduce burden on them during clinical trials35. Nowel et al.23 aim to evaluate the relationship between digital measures collected from a smartwatch and electronic patient-reported outcomes (ePRO) via a smartphone in patient with RA. Fatigue is measured using a daily fatigue numeric rating scale36 and the weekly PRO measurement information system-computer adaptive test (PROMIS-CAT). Tam et al.24 explore the use of an On-demand Program to EmpowerR Active Self-Management (OPERAS) to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in a patient with RA that incorporates disease activity and symptom monitoring along with time spent on physical activity using a Fitbit Inspire. The aim of the study is to determine whether this technology can help with self-management of the disease. Digital outcomes will be measured using SenseWear Mini (BodyMedia, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA), which uses a trial-axial accelerometer to estimate measurements such as level of physical activity, step counts, energy expenditure, and metabolic equivalent of tasks. Fatigue is measured using the FSS. Platchta-Danielzik et al.25 aims to use digital devices to measure changes in patients with UC undergoing filgotinib treatment over a 2-year duration with the hope of improving patient care through remote monitoring. Participants will wear a Garmin Vivosmart 4 (Garmin Ltd., Olathe, Kansas, USA) and a SENS motion sensor (SENS Motion, Copenhagen, Denmark) for 7 days after each follow-up visit. These sensors will be used to track steps, heart rate, stress level, sleep pattern, and movement types. Fatigue is measured using the IBD Fatigue Score. These clinical trial protocols demonstrate the commitment to leveraging the rise of digital technologies to measure outcomes, both within the clinical setting and remotely. The ultimate goal is to utilize these technologies to enhance patient care and drive advancements in drug development.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the only systematic review to date regarding the use of DHT and imaging to measure fatigue in IMID. The majority of the studies included in this review were published within the last 5 years (68.8%). This indicates a recent increased interest in exploring the use of DHT and imaging for measuring fatigue in IMID. The current endpoints are heavily skewed toward using MRI to measure fatigue given that the area is more matured in its development. The recent development of wearable sensors has brought the focus on continuous and passive monitoring of patients at home and in the clinic to develop novel endpoints to measure fatigue in patients with IMID while reducing the burden on the patients. Traditionally, patients who are undergoing treatment or participating in clinical trials often visit the clinic for assessment. The experience of going into the clinic and undergoing an MRI can be burdensome for patients. DHT provides an opportunity to collect data that is representative of patients’ symptoms and experiences in their daily life. These data could provide deeper insight into the biological course and effects of disease, including disease-related fatigue.

Overall, most of the studies included in this systematic review found significant associations between fatigue PROs and the digital and imaging endpoints. The results of the brain MRI studies suggest that IMID fatigue affects the brain both structurally and functionally and suggests that fatigue could be biologically associated with central nervous system impairment. In contrast, the results of the full-body and joint MRI studies suggest that IMID fatigue is not explained by current measures of disease activity, inflammation and skeletal muscle tone. Therefore, fatigue must be studied independently of disease activity.

Studies by Antikainen et al.10 and Rao et al.22 provided evidences that wearable devices may be able to collect digital biomarker endpoints significantly associated with fatigue PROs. However, more studies using wearable sensor devices to measure fatigue must be conducted to add greater weight and significance to this finding. The low correlations found between fatigue PROs and sleep-related digital endpoints implies that fatigue is not simply caused by lack of quality sleep alone. Based on the results of the included studies, IMID fatigue appears to be of multifactorial nature. Rao et al. recognized the multidimensional nature of fatigue and developed a model to predict mental and physical fatigue that integrated subjective measures derived from PRO (e.g., mood, pain), objective measures from wearable sensors (e.g., heart rate, sleep quality, physical activity), and demographic data (e.g., age, gender)22. Imaging and digital devices capture data that is not accessible through PROs and do so at a higher frequency and resolution, enabling a more holistic assessment of fatigue. Contradictory findings from these studies demonstrate the difficulty of generalizing imaging and digital biomarkers related to fatigue given the heterogeneity across these studies. Considering the importance of PROs and complex associations with digital measurements, further research is needed to identify how disease assessments can be optimized by amalgamating PROs, digital, and imaging endpoints.

While most of the studies included in this review feature the use of imaging to measure fatigue, there is a call to develop more digital devices to measure fatigue given their benefits to patient care. Wearables offer a means to measure fatigue continuously during daily life, while imaging techniques provide only a snapshot. Given that fatigue tends to fluctuate due to personal, social, and environmental factors, it is imperative to measure fatigue in a natural environment. Furthermore, wearable devices can be integrated into a software platform to enable the capture of multiple data streams to better characterize the multidimensional nature of fatigue. In addition, accurate capture of fatigue using wearables can potentially allow for better management of fatigue, thus improving the quality of life for people living with autoimmune diseases37. With the proliferation of smartwatches, there is potential to leverage the data set to develop a comprehensive measure of fatigue.

This systematic review has limitations which must be addressed. First, only two databases were searched, which limits the scope of the review. Many of the included studies had small sample sizes and had short durations (<3 months), so there is risk that the findings are not generalizable. Additionally, there were a variety of PROs used across studies, which creates heterogeneity and makes it difficult to compare and extrapolate findings between studies. PROs are subjective and limited in sensitivity; this limits the ability to detect associations between fatigue and DHT and imaging endpoints. There was varying use of medications across studies, which potentially affected biomarkers and skewed study findings. This systematic review explored fatigue across multiple IMIDs rather than examining each IMID independently. It is unknown whether the biological mechanism of fatigue is the same across all IMIDs; exploring fatigue across multiple IMIDs might negate the mechanism and effect of fatigue in different diseases. Additionally, meta-analysis was not performed, which limits the depth of this systematic review.

As shown in this systematic review, DHT and imaging present an opportunity to increase our understanding of the biological mechanism of fatigue. The results of the included studies are promising for how DHT and imaging can be used to establish quantitative, objective measures of fatigue. However, very few studies have been completed. There are only two published papers using DHT for IMID fatigue measurement, both of which are from the same study. This highlights the knowledge gap within the field and the need for more research to be conducted.

This review highlights the need for future research to investigate fatigue independently from disease activity and inflammation, as fatigue appears to be decoupled from disease activity. This is evidenced by the fact that fatigue persists in patient in in clinical remission. Further research will help us to gain an understanding of the biological pathway of fatigue within the body. This knowledge will allow us to target the fatigue pathway in therapeutics with the goal of treating fatigue as the disease itself is treated. Although IMID fatigue is a challenging issue, it is important to keep pursuing because of its importance to patients.

This review has identified significant heterogeneity in the tools used to evaluate fatigue, which poses challenges for comparing results across studies and generalizing findings to different disease populations. Fatigue is inherently a subjective measure, and various subtypes of fatigue such as physical, mental, and cognitive fatigue further complicate the assessment when relying solely on PROs. The integration of digital and imaging technologies provides a valuable opportunity to collect information about the patient that complements data from PROs; thus, providing a more comprehensive understanding of fatigue and enabling the identification of the subtype of fatigue. Given the mixed findings observed in this study, the continued development of these tools is essential to ensure that digital and imaging technologies accurately capture the multidimensional nature of fatigue. Based on these findings, we recommend that future research should focus on:

-

Developing a framework to systematically evaluate different subtypes of fatigue.

-

Standardizing imaging techniques and PRO assessments to facilitate better comparison and understanding of fatigue.

-

Developing and integrating digital tools that can effectively and continuously capture different streams of data such as physical activity, physiological vital signs, and sleep quality to better characterize fatigue.

-

Incorporating both subjective and objective measures to comprehensively assess the multidimensional nature of fatigue.

As digital and imaging technologies continue to evolve, they have the potential to enhance our understanding of fatigue using objective data derived from various modalities to build a more comprehensive model. By effectively integrating these innovative tools with traditional assessments, we can pave the way for improved outcomes in patients with IMIDs.

Methods

Search strategy

The review was conducted in line with the PRISMA guidelines38 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). A database search of PubMed and Cochrane Library from 2003 to June 2023 was conducted. Keywords for subject-specific searches were combined using the “OR” boolean operator; the components were combined using the “AND” boolean operator. For the Cochrane Library search, all keywords were searched within the title and abstract field. Common terms such as fatigue, DHT, and imaging were searched along diseases, such as RA, systematic lupus, Sjögren’s syndrome, and IBD. The complete keywords and search strategy used are outlined in Supplementary Table 3.

Study selection

The references obtained from the search were stored, managed, and screened using the Rayyan web platform for systematic reviews39. Duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers (H.M. and H.N.) screened the titles and abstracts. The following inclusion criteria were applied: DHT or imaging used in the study; adults diagnosed with RA, pSS, SLE, or IBD (UC and CD); fatigue PROs assessed in relation to DHT or imaging endpoints as a primary or secondary outcome. References not written nor available in English were excluded. References not agreed upon for inclusion/exclusion by both reviewers were discussed by the two reviewers to reach a consensus. References agreed upon for inclusion by both reviewers were retrieved for full-text review. The full-text review was completed independently by the same two reviewers. References were excluded for the following reasons: incorrect disease cohort; did not provide relevant outcomes and data pertaining to associations between fatigue and DHT or imaging endpoints.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was completed by H.M. Information collected included: primary author, publication year, study sample size, average age of participants, participant gender distribution, remission status, average disease duration, digital or imaging technology used, digital endpoints measured, fatigue PRO used, whether associations were found between fatigue PROs with digital endpoints, and whether medications were included in the studies. The data of interest were the conclusions of whether significant associations, set as p < 0.05, were found between fatigue PROs and the digital and imaging endpoints. Study quality was assessed using the STROBE checklist for observational studies40 and the levels of evidence were determined based on the design of the study41.

Responses