A systematic review of healthcare experiences of women and men living with coronary heart disease

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) has historically been perceived as a disease affecting middle-aged men; however, it is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity for people globally1. Literature highlights women with CHD experiencing poorer short- and long-term outcomes relative to similarly affected men, with further disparities in care and outcomes observed for subgroups of women especially among racial and ethnic minorities, women with lower education levels and those socially disadvantaged2,3,4,5.

Despite decades of awareness campaigns and education, quantitative studies from around the world have demonstrated gender differences at all stages of the healthcare journey, from primary care through to secondary prevention. In a study of just over 53,000 individuals (58% women, 42% men, 0% non-binary/gender diverse people), women were less likely to have a cardiovascular risk assessment conducted in primary health care services (odds ratio (OR) 0.88 [0.81 to 0.96])6. This disparity in the management of vascular disease was also reported in a study of more than 130,000 patients (47% women, 53% men); which reported women were less likely to be prescribed recommended medications and assessed for cardiovascular risk by their general practitioners7. Gender differences are also reported in relation to hospital presentation, with two large-scale studies in America and Sweden observing a link between women’s prehospital delays and greater mortality rates following ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarctions8,9.

Further gender differences can be seen with treatment upon arrival at a tertiary hospital. For example, an Australian study that investigated 54,138 people (48.7% women) who presented to three emergency departments experiencing non-traumatic chest pain reported that women received suboptimal care relative to men as they transitioned through the health service: compared with men, women were significantly less likely to be seen within 10 min of arriving at the emergency department, less likely to have a troponin test undertaken, less likely to be admitted to specialised care, and more likely to die during their hospital admission (OR 1.36 [1.12, 1.66])10. Moreover, regardless of age, more women will die within a year of a first acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (26% of women compared to 19% of men) and will have complications of heart failure and stroke within 5 years of their first AMI (47% of women vs. 36% of men)11. These findings imply the existence of a structural gender bias in healthcare settings towards the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of CHD, which has been supported in the literature. For example, a study of over 500 cardiologists in the US reported an implicit gender bias in simulated clinical decision-making for suspected CHD, with the majority associating strength or risk taking implicitly with male more than female patients12. Another recent research concluded that among patients resuscitated after experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, discharge survival was significantly lower in women than in men, especially among patients considered to have a favourable prognosis11. The existence of gender bias persists in secondary prevention. For example, in a study of 9283 individuals with acute coronary syndrome patients (29% women, 71% men), women had lower odds of attending cardiac rehabilitation compared to men (OR 0.87 [0.78, 0.98])13. Further, a review of the literature found women to have lower referral, enrolment and completion for important secondary prevention programs such as cardiac rehabilitation14. However, it is important to note that these observations have focused on sex (biological, physiological, hormonal, genetic) differences rather than gender (described often as socially constructed through shared structures and experiences). It is also important to note that these studies have relied on a binary conception of sex and gender that is now considered both inappropriate and inaccurate with growing evidence on the spectrum-like nature of these concepts15.

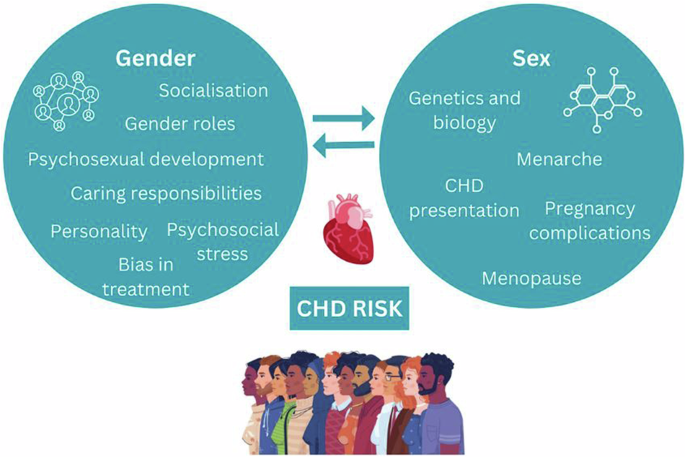

The terms sex and gender are often conflated in the scientific literature16. While sex is considered to be an important biological determinant of health accounting for physiological differences, gender, also requires consideration for its influence on health outcomes (refer Fig. 1). Gender identities, socialisation, roles, and access to resources are factors that have been shown to contribute to health outcomes17 with increasing evidence of the influence of psychosocial development as a result of genetics, hormonal and psychosocial influences for additional consideration18.

The role of sex and gender of CHD risk.

A previous systematic review explored patients’ experiences of CHD using a gender-sensitive approach19. The review included 60 qualitative studies (published before 2004), and the identified studies were conducted almost exclusively with men until the late 1990s when the focus changed to women. However, they noted that most studies did not have a gender focus and called for more work taking gender roles into account when exploring experiences of people with CHD.

In supporting improved outcomes in people’s heart health, more research is needed to examine the reasons for evidenced, gender-based disparities. Exploring the lived experiences of CHD from the perspective of multiple genders beyond the gender binary will promote a deeper understanding of the healthcare journey and inform interventions for CHD management20. Therefore, the aim of this study was to synthesise qualitative research on experiences and perceptions of CHD and associated healthcare from the perspective of people of any gender identity with CHD and their healthcare professionals.

Results

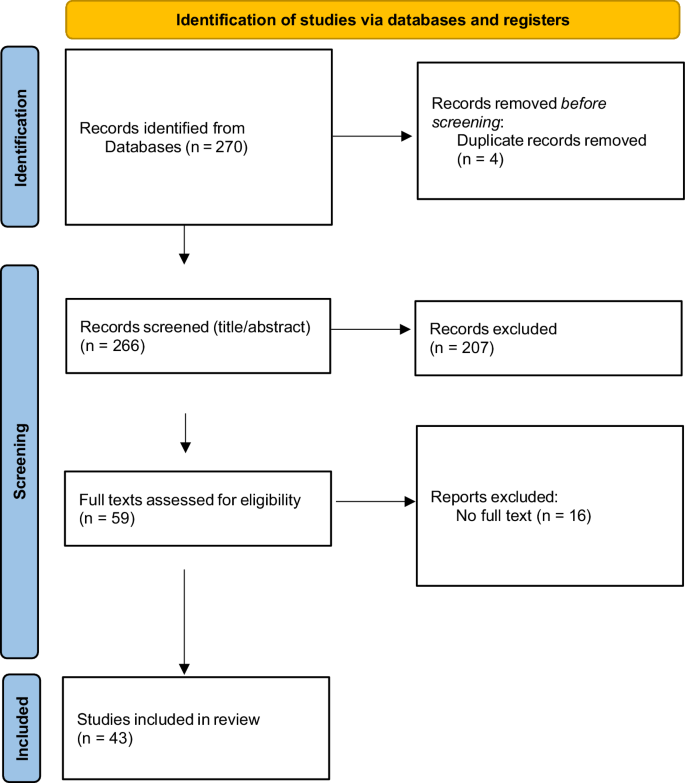

In total, 266 studies were screened, of which 43 studies were included (Fig. 2). Eleven studies were conducted in the United States of America21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, nine were from the United Kingdom32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, seven were from Canada41,42,43,44,45,46,47, five were from Sweden48,49,50,51,52, three were from Australia53,54,55, two were from Finland56,57, and one study each from Austria, Brazil, Denmark, Italy, New Zealand, and Spain (Supplementary Table 1)58,59,60,61,62,63.

PRISMA Flowchart.

Of the included studies, a total of 1522 people (62% women; people with CHD or CHD health professionals) were included. Twenty studies focused on the experiences of women with CHD22,24,28,29,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,47,48,49,50,53,55,63, three studies focused on the experiences of men with CHD46,60,62, 19 studies included a combination of women and men21,23,25,26,27,32,33,35,42,43,44,52,54,56,57,59,61, and two studies did not report gender breakdown31,51. There were no studies that reported non-binary, gender diverse, or transgender people. Three studies included healthcare professionals only31,51,58, one study included people with CHD and healthcare professionals30, and one study included people with CHD and carers45.

A variety of qualitative data collection methods were utilised, including interviews, interview following presentation of vignettes, content analysis, and focus groups. Few studies provided summary statistics on socioeconomic status (n = 6) and education (n = 14), respectively. The heterogeneity and limited data inhibited our ability to combine the data for meta-analysis.

Quality assessment

Among the included studies, 8 (18.6%) were rated as high quality, 29 (67.4%) as medium quality and 6 (13.9%) as low quality (Supplementary Table 1). The six low quality studies differed from the high-quality studies as they lacked a coherent explanation of theoretical underpinnings of their study design and did not adequately consider the relationship between participants and researchers. Low quality studies were sporadically spread across this study’s thematic outcomes, therefore minimising risk of bias.

Study themes

Four major themes were identified: assumptions about CHD (interpretation of signs and symptoms, help seeking); gender assigned roles; interactions with health care; and return to ‘normal’ life.

Assumptions about CHD: Interpretation of signs and symptoms

Studies reported that women and men held assumptions regarding CHD, particularly around their perception of who was a ‘typical’ heart attack candidate.

The assumption of CHD as a ‘man’s disease’ was cited frequently and led many women to question their own signs and symptoms. Women reported a high level of uncertainty about their symptoms (n = 12 studies), often attributing any signs or symptoms to non-cardiac causes such as old age, arthritis, or fatigue and often trying to persuade themselves that the symptoms would disappear with rest22,23,24,28,30,35,36,37,41,48,49,60. This was often linked to symptoms not aligning with what women thought as a ‘typical heart attack’, as there was no acute crushing chest pain as often described, instead, often reporting a gradual onset of symptoms such as feelings of nausea and breathlessness, causing a level of confusion and delays in seeking help28,31,32,53,58. In contrast, men were more explicit in their symptom descriptions and more commonly recognised them as cardiac symptoms, that warranted medical attention23,60,63 Riegel et al.23 suggested this was due to men being more confident in their decision-making, having greater social support and symptoms being more aligned with the public perception of CHD as a man’s disease.

Similarly, identifying CHD signs and symptoms were also more difficult due to assumptions of the typical ‘heart attack’ patient – often described in studies as male, overweight, smokers, who did little exercise. Participants were therefore confused as to what was happening if their own self-image differed, especially women who thought they were not at risk unless they had adopted ‘a man’s way of life’23,38,39.

Assumptions about CHD: help seeking

Women often delayed seeking medical help, preferring to ‘wait and see’. Studies reported the delays were often due to confusion over signs and symptoms not aligning with prior perceptions of CHD, with women self-medicating or resting to see if the signs would pass before ‘bothering’ others23,27,30,33,37,58. Studies described women not wanting to be seen by others as a ‘nuisance’, ‘ignorant’ or a ‘hypochondriac’ and as such, they were more likely to wait until they were incapacitated to seek medical help.

Women also spoke of important activities and responsibilities that prevented or forestalled seeking medical attention22,49,52. Concern for the family often led to ignoring symptoms, because responsibilities, such as housework or caring for other family members, could not be delegated to others, and treating symptoms failed to ‘fit’ into their lives22.

Seeking advice from friends or family before seeking medical attention was commonly reported by both women and men, with many only seeking healthcare due to the friend or family member’s insistence. Immediate family members, usually daughters, were instrumental in organising medical attention37. Wives were commonly the impetus for men to seek help, insisting on them acting on symptoms and seeking care37,40,52 and this was reported by Brink et al.52 as being one of the reasons why men sought medical attention faster than women. However, it was not reported that husbands were the impetus for women to seek help.

Women delaying seeking professional medical care was also often due to logistical concerns such as inadequate transportation, workforce shortages at medical centres, and waiting times, especially in regional or rural areas22,29,54.

Rosenfeld et al.29 reported that women preferred to visit a general practitioner rather than engaging with emergency services as they often felt that their symptoms were not severe enough to waste emergency services time.

Gender-assigned roles

As previously described, women commonly spoke of their sense of responsibility for family and home and prioritising their duty to others over their own health needs. The interruption to normality in everyday routines for the women reportedly caused anxiety and many attempted to hide their feelings to shield family members from concern22,49. Studies reported that women were keen to be discharged from hospital following treatment, although many women reported fears of the future and fear of implication of the illness on their roles as family carers40,47,55.

This sense of responsibility for family and home was less often noted by men. Studies observed that men were often more concerned about their social position and concerned with how their recovery period might impact the way they were seen by others or how they would reconcile with their role as the ‘breadwinner’ of the family if they were forced to decrease their workload44,45.

Cewers et al.51 reported that health professionals tended to have specific gendered role perceptions, influencing advice regarding recovery at home. Men were seen as the ‘workers’ and were more likely to do sport than women, whereas women were seen as the carers and housekeepers and were more likely to participate in yoga and walking in their recovery.

Interactions with healthcare

Four studies specifically focused on patient experiences with health care professionals, with gender differences apparent in these interactions22,30,56.

Women described not being ‘listened to’ by health professionals and often reported being dismissed due to the lack of specificity of their symptom descriptions22,40,55. Women also voiced frustration with the lack of information provided regarding their initial diagnoses and discharge40,55. This finding was related to their need to organise their domestic duties and for their ‘forward planning’.

In contrast, health professionals identified that they often saw women as emotional and ‘in distress’, unable to articulate their symptoms clearly, which made it difficult to reconstruct pain development51,58. These studies concluded that women were more difficult to diagnose as they were often presenting older, had more complex conditions and were in later stages of illness due to delayed help seeking.

Women tended to have stronger emotional responses to their diagnosis than men, with most women reporting sadness and resignation26,40,59. Checa et al.59 described women’s concern about the future and how their disease could affect their roles within the family, whereas men tended to be more relaxed and even optimistic about being ‘cured’. However, this contrasted with Evangelista et al.26 who reported women used more optimistic coping strategies than men, who tended to use more emotion-focused and fatalistic coping strategies.

One study, focused on men’s psychological reactions and experiences following a cardiac event, reported participants had difficulties in adapting to their new postcardiac identity and accepting their new ‘roles’46.

Return to new normal

A desire to return to a familiar lifestyle was reported by both women and men40,44,47,55. However, women were more often concerned about the practical support they would need on returning home (e.g., shopping, cleaning) than men, and it was reported that women became avid planners in their recovery to ensure returning to their ‘normal’ lives as soon as possible47. Men reported being fearful of being discharged home as they were unsure of what life would look like in terms of employability, sexual virility, and other’s perceptions of them44,45.

On returning home, women often spoke of loss of control of their home situation and appeared to equate this loss of role functioning with a diminution in their value as a person34,45,47. Women reported being happy to talk and discuss their illness and hear from other patients, whereas men were less likely to want to share any thoughts and feelings and often self-isolated44,52.

Discussion

This review suggests that whilst the experiences of people with lived experience of CHD are very individualised, there are gendered experiences and perceptions of CHD and associated healthcare. A greater proportion of women participants were included in this review, which contrasts to all men-only studies prior to 199019. The themes identified in this review will be discussed according to the Ecological model of health behaviour, as it highlights how gendered experiences span across the multiple levels of influence64.

The findings of intrapersonal factors suggest that the perception of CHD as a ‘male disease’ persists among individuals and healthcare professionals, which influences the CHD ‘journey’ from symptom recognition to rehabilitation for both patients and health professionals. Women were reported to be more likely than men to seek help in primary care settings, similar to other conditions such as whiplash trauma and mental health52. However, when seeking emergency care, women were reluctant to burden the hospital system as they lacked knowledge on the urgency of their CHD symptoms, and sometimes did not perceive themselves at risk. Furthermore, similar to previous findings, women continue to prioritise their family carer role over their own health22. It is possible that these compounding factors will continue to delay women in presenting with CHD symptoms to emergency and with later presentations, additional co-morbidities can exist, making it more challenging for health professionals to treat effectively. Hence, potentially placing greater pressures on the health system.

Efforts need to be made through health education to dispel gendered perceptions, such as myths of CHD being a ‘male disease’ and building awareness on socialised gender norms of women’s health seeking behaviour to ensure women recognise early signs and symptoms, that can differ to men’s symptoms and seek help in a timely manner. The CHD journey has been expressed as stressful from all counterparts, and men with CHD have more commonly expressed to feel isolated throughout their journey. As part of patient management, additional efforts by health professionals should incorporate emotional and mental health interventions and offer social support to CHD patients65. Women also reported feeling dismissed by health professionals during their care, however whether their experiences were influenced by gender could be debated as fewer men’s perspectives were available for comparison. These interpersonal factors however continue to highlight the importance of patient communication and patient centred care.

A pathway through which the gender system impacts health is through gendered health service provision, which can act to disempower gender groups, or leave their health needs unmet66. Traditionally, medical training has been aimed to be predominantly gender neutral, that is, little or no attention paid to gender differences in medical education. Yet, the interpretation of CHD signs and symptoms are more aligned with men, potentially as CHD research has disproportionately underrepresented women participants, and women’s presentations have been perceived by health professionals as ‘atypical’. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the differences in symptom presentation in men and women demonstrated that women are more likely to report experiencing shoulder and neck pain, palpitations and nausea, whereas men are more likely to experience chest pain. However, it was also noted that there was significant overlap of the symptoms experienced and therefore symptoms should no longer be labelled as ‘typical’ or ‘atypical’67. Furthermore, some have long argued for the need to address gender bias and develop gender competencies in medical curricula68, and this review continues to support such recommendations. Challenging conservative practice means holding CHD health professionals, organisations, and systems accountable to their assumptions, knowledges, and practices that bias male experiences over others. Gender-sensitive approaches to care which are responsive to people’s lived experiences and particular needs, preferences, identities and circumstances should be emphasised.

Women reporting inadequate transportation, healthcare staff shortages and waiting times had impacted them seeking medical care and were outcomes in women-only studies. These institutional factors require further exploration across the gender spectrum to determine whether a true gendered experience exists on these barriers to accessing CHD care.

With women becoming more educated and increasing their labour force participation, we might expect to see a change in gender norms and therefore potential health behaviours. However, this review continues to affirm previous findings that gender norms remain relatively stagnant, where post-diagnosis and returning home, women are concerned about their abilities for undertaking domestic duties, while men are concerned about employability and family financial responsibilities. The traditional gender roles might be due to the older age of participants, but overall, all patients grappled with their identities and societal roles while living with CHD. Though not all patients fall into the distinct gender social norms, health professionals should consider individual’s expressed identity that can influence their responses and behaviours towards CHD.

Future research into gender disparities should avoid the traditional binary labelling of sex and gender into ‘male’ and ‘female’ categories and instead, adopt a more realistic and more inclusive approach that considers sex and gender as operating across a spectrum.

This review included studies over a 22-year period, yet only 8 of the 43 studies were published in the last 11 years. While notable changes in CHD care have occurred, the more recent studies continue to report similar gender differences across all the identified themes. Moreover, the responsiveness of health care professionals and perceptions of patients may have differed, including those who identify as gender diverse, those with different socioeconomic status and education levels, as well as low- and middle-income countries where the majority of CHD deaths occur69. This review also excluded studies published in languages other than English, hence limiting perspectives on healthcare experiences and behaviour from non-English speaking countries with differing cultural and social norms.

The findings from this review highlight differences in healthcare experiences of women and men living with coronary heart disease. However, there are still major gaps in the research. While some quantitative studies from low-middle-income countries have been located70,71, more qualitative research from low-middle-income countries is needed to provide comparisons with the developing world and better inform tailored intervention strategies.

None of the included papers explored the experiences of gender diverse people. Recommended areas for further investigation include the experiences of transgender, gender diverse people, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, and minority groups (e.g., indigenous people or people with disability). Intersectionality describes the ways in which different parts of a person’s identity can overlap to increase the experience discrimination and marginalisation72. It is important that future research adopts an intersectional lens, to explore how various factors such as gender, class, ethnicity, (dis)ability, rurality, sexuality and age impact the experience of CHD.

Future research should also explore gendered CHD experiences over time, as factors such as increased public awareness CHD campaigns, changes in health professional education content and changes in the number of women included in CHD research studies may influence findings.

In narrowing the disparity between men’s access and treatment for CHD compared with women, non-binary, gender diverse, and transgender people, a number of major health initiatives have been introduced aiming to raise awareness of cardiovascular health. For example, the Australian ‘Her Heart’ initiative aspires to educate and empower women to decrease their risk of developing heart disease and the American Heart Association’s ‘Go Red for Women’ campaign which similarly aims to empower women to take charge of their heart health64,73. Both campaigns encourage women to participate in heart disease research, raise awareness of women-specific CHD risk factors and ‘break’ the myths around heart disease being a predominantly male concern. However, many of these health campaigns target the sex difference in CHD risk, such as understanding the signs of CHD in women. More focus needs to be done to elevate the lives and lived experiences of people whose sex and/or gender identity is more expansive than the conventional man-women binary.

While the awareness of sex and gender influencing CHD research, medicine and public campaigns grows, the perception of CHD as a ‘male problem’ is longstanding. If not dispelled, this may lead to people continuing to be underdiagnosed and inadequately and inappropriately cared for. Additionally, and albeit gradually, gender norms will evolve, so we cannot underestimate how individuals’ gender can impact their presentation, reaction and approach to living with CHD. As we also shift healthcare to personalised care, gender-sensitive approaches are needed to support health professionals and society to embrace a broader disease paradigm, through education, public health messages, patient advocacy and promote patient-centred multidisciplinary care.

Methods

The review was undertaken in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines74 (Supplementary Table 1) and the protocol is provided here. Due to the qualitative nature of this review, the background, experiences and biases of authors involved in this review should be acknowledged as they potentially influence the content. Therefore, we believe it is important to reflect on our own positionality. The author group reflects a diverse range of genders and cultural backgrounds and are a cross-disciplinary team of practitioners (rural and metropolitan), all committed to promoting CHD health care. They worked reflexively together in reviewing and synthesising the data to reduce unconsciously imposing personal beliefs and assumptions. In this way, the author group was committed in remaining mindful of the benefits and challenges of conducting research from an insider–outsider perspective.

It is also acknowledged that the current evidence presented in this review comes primarily from Western cultures and this geographical and cultural context may shape the findings as they may not universally apply due to cultural differences in gender norms and expectations.

Search strategy

The search and inclusion strategy received contributions from authors HB, JL and SG and was reviewed by a University Librarian not otherwise involved in the review. Specific search terms (along with their synonyms, combinations, Boolean operators, and relevant MeSH/Subject terms) were identified based upon the review question (Supplementary Table 2). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed using the SPIDER tool75 (Supplementary Table 3). The following databases were searched: MEDLINE Complete, CINAHL, PsychINFO, SocINDEX, Academic Search Complete and EMBASE. The search was limited from 2000 to 2023 and adjusted to suit the requirements of specific databases.

Study selection

The screening process was facilitated by Covidence (Veritas Health Information, Australia). Acknowledging the challenges with how qualitative research is indexed in electronic databases76, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied in two steps, by two researchers (HB, JL), independently: (1) the Sample, Evaluation, and Research Type components on screening title and abstracts of retrieved records, and (2) the Phenomenon of Interest and Design components were applied at the full-text review stage. If any disagreements occurred, discussions were held with a third reviewer (SG) to reach consensus.

Quality assessment

Two researchers (HB, LL) independently assessed the methodological quality and risk of bias of each included article using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme’s Qualitative Checklist (CASP-Q)77. Each article was assigned a “high”, “medium”, and “low” quality rating from the CASP-Q scores using Butler, Hall, and Copnell’s recommendations78. These quality ratings were not used to further exclude articles, but rather to inform on the potential weaknesses of the identified themes.

Data extraction

Summary data were collected from each article including (HB, CB, LL): author, year, country, sample, mean and range of age, proportion of women, socioeconomic status, education levels, CHD type, study design, evaluation and research type (Supplementary Table 1). Study findings, along with direct participant quotes, were extracted from each article (HB, CB) using NVivo (Version 20)79.

Data synthesis

Data synthesis involved an inductive thematic synthesis using the methodology by Thomas and Harden80, supported with NVivo software. Two researchers (HB, JL) familiarised themselves with each article and then conducted line-by-line coding of text relevant to the synthesis aim. Articles were then loaded into NVivo Version 20 and independently coded by the two researchers (HB, JL). The researcher specific coding frameworks were then compared, discussed, and merged into one, accounting for bias. The identified themes were then generated in an iterative process to ensure accuracy and completeness. This stage involved an initial review by a broader team (HB, LL, CB, JL) to achieve consensus, and then presented to the whole authorship team for comment.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in this study.

Responses