A transient memory lapse in humans 1–3 h after training

Introduction

In the realm of human learning, a key component of interest is learning retention–the ability to recall what has previously been learned. Retention performance in humans is typified by one of three patterns. It either remains constant over the time period examined, declines after a short or long delay from the end of training, or initially improves and then remains constant or declines. Not included in this list is an additional pattern that has been identified in non-human species. In that pattern, retention performance declines at some time point after the end of training and then improves again, revealing a U-shaped function: a transient memory lapse. Here we briefly review the evidence and proposed explanations for transient memory lapses in non-human species, note the few previous examples of transient memory lapses in humans, suggest reasons why further evaluation of transient memory lapses in humans is warranted, and report two new cases of transient memory lapses in humans for a learning type for which transient memory lapses have not been documented previously: perceptual learning.

The presence of transient memory lapses within the retention curve was first documented in rats for avoidance learning. Kamin (1957)1 was interested in the idea that avoidance learning might pass through an incubation period, that is, that avoidance learning might be minimal soon after training but grow with time. To investigate this possibility, he trained rats on an avoidance-learning task to a low level of avoidance responding and then tested different groups at different time points after training to evaluate retention. The resulting retention curve was clearly U-shaped. Retention was high immediately after training, was significantly lower 0.5, 1, and 6 h after training–approaching pre-training levels at the 1-h time point–and then returned to the initial high value 24 h and 19 days after training. Thus, learning that was demonstrated at a previous time point after training was temporarily lost and then returned, documenting a transient memory lapse. The phenomenon became known as the “Kamin effect” (not to be confused with the “Kamin blocking effect”).

In the ensuing years, there have been numerous reports of transient memory lapses in a wide variety of non-human species for a wide variety of learning types. The species include, for example: ape2, rat1,3, mouse4, rabbit5, chick6, pigeon7, octopus8, cuttlefish9, goldfish10, sea slug11, pond snail12, honeybee13, and cockroach14. The learning types include, for example: appetitive classical conditioning12,13,14; aversive operant conditioning1,3,4,6,8,9,10; conditioned suppression7; extinction learning5, appetitive15 and aversive16 y-maze discrimination learning; aversive non-associative learning11; episodic-like learning2,17, and social learning18. The lapses manifest in two primary patterns. In one pattern, relearning over a set of trials after a period of forgetting is slower than normal during the period of the lapse e.g., 1,3,19. In the other pattern, performance based on a single value, such as the duration of a specific behavior or the number of specific behaviors exhibited within a fixed time window, returns to naïve levels e.g., 11,12. Frequently there is more than one transient memory lapse during the early post-training period. The timing of the lapses varies across species and task, though the lapses usually occur within tens of minutes to several hours after training.

A commonly proposed explanation for transient memory lapses is that they reflect periods of transition between different memory phases. At least three memory phases beginning in the first minutes after training have been identified functionally in non-human species. These phases are referred to as short-term memory (STM), intermediate-term memory (ITM), and long-term memory (LTM). Each phase has distinct kinetics as well as distinct molecular requirements e.g., 11,20,21,22. STM typically lasts minutes to tens of minutes (not <30 s as the term is used in the human-learning literature) and does not depend on protein synthesis. ITM lasts tens of minutes to hours and relies on protein synthesis but does not require transcription. LTM lasts hours to days and relies on protein synthesis and transcription. These three memory phases bear some resemblance in their kinetics and molecular requirements to the three phases of long-term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic transmission–early LTP, intermediate LTP, and late LTP—which are presumed mechanisms of memory storage23,24,25,26. The idea is that transient memory lapses occur when there are time gaps between the end of one memory phase and the beginning of another. It has also been suggested that transient memory lapses reflect temporary failures in memory retrieval that arise because internal cues that were present during training fluctuate during the first hours after training–remaining for a period, waning, and then returning–and that retrieval is disrupted when the internal cues differ from those that were present during training19,27,28,29.

The considerable evidence for transient memory lapses in non-human species suggests that transient memory lapses reflect a fundamental aspect of learning11,13. If so, transient memory lapses should be a prevalent component of retention curves in humans. However, little attention has been paid to this possibility. There appear to be only three reported cases of transient memory lapses in human learning–for memory for melodies30, exposure-induced reduction in fear responding31, and retention of spatial working memory32 –and these reports have largely been ignored: the most recent report was published 25 years ago, there are 10 or more years between successive reports, and transient memory lapses, whether in humans or non-human species, are not mentioned in representative reviews of memory retention in humans33,34,35. Thus, consideration of transient memory lapses in the normal retention curve has not entered the main-stream human-learning literature.

The prediction that transient memory lapses are a prevalent, albeit currently unrecognized, component of retention curves in humans is worth additional testing for at least four practical and theoretical reasons. First, if present in human learning, transient memory lapses would lead to underestimation of key memory measures depending on the timing of post-training tests relative to the lapse. If the tests all occurred during a lapse, raw memory performance would be underestimated, because the memory would appear to be intrinsically weak, rather than temporarily weaker than before and after the lapse. If the tests only occurred before and during the lapse, memory duration would be underestimated, because the memory would appear to be fading at the final testing time due to the lapse. If the tests only occurred during and after the lapse, the rate of memory emergence would be underestimated, because the memory would appear to be emerging only after the lapse. Second, if present in human learning, transient memory lapses would provide another behavioral means to investigate the time course of human memory formation, adding to the current small repertoire of evaluations of the time courses of retrograde learning interference and learning emergence. Third, if present in human learning, transient memory lapses would provide insight into memory disorders if the presence, number, or kinetics of the lapses are altered by those disorders. Fourth, if present in human learning, transient memory lapses would provide evidence consistent with the possibility that the different memory phases (or varying internal cues) presumably demarcated by the lapses rely on the same molecular processes in humans that have been identified in non-human species.

With these motivations in mind, we asked whether transient memory lapses occur in humans for a learning type for which transient memory lapses have not been previously evaluated. The learning type we selected is perceptual learning–the improvement in perceptual ability with practice. We selected perceptual learning in particular because it differs in two key respects from the learning types for which transient memory lapses already have been documented. First, previous reports of transient memory lapses are restricted to learning types that require only a few training trials to induce a lasting memory. In contrast, perceptual learning often requires extensive training within a restricted time period for the same outcome36,37,38. Second, previous reports of transient memory lapses are for learning types that yield memories of experiences (a foot shock and how to avoid it, a tail shock leading to sensitization of the gill-and siphon-withdrawal reflex). In contrast, perceptual learning yields a new or improved skill or ability. Therefore, the present investigation of transient memory lapses in human perceptual learning simultaneously provides tests of two predictions of the idea that transient memory lapses reflect a fundamental aspect of learning: that transient memory lapses should be a prevalent component of retention curves in humans and should also occur even for learning types that differ markedly from the learning types that have already been examined.

Specifically, we trained six groups of human adults on one perceptual task (auditory interaural-level-difference (ILD) discrimination) and then tested each group on either the trained task, or on a related untrained perceptual task (interaural-time-difference (ITD) discrimination) at one of three time points after training: 30 min, 1–3 h, or 6–10 h. We report that, for each tested task, there was learning at 30 min and 6–10 h after training, but less or no learning 1–3 h after training, documenting a transient memory lapse at the 1–3 h time point. The lapses in perceptual learning 1–3 h after training in humans mirror the lapses reported for other learning types in non-human species. Thus, transient memory lapses may reflect a fundamental aspect of memory formation, and be an overlooked feature of human learning.

Results

Mean performance during training and testing

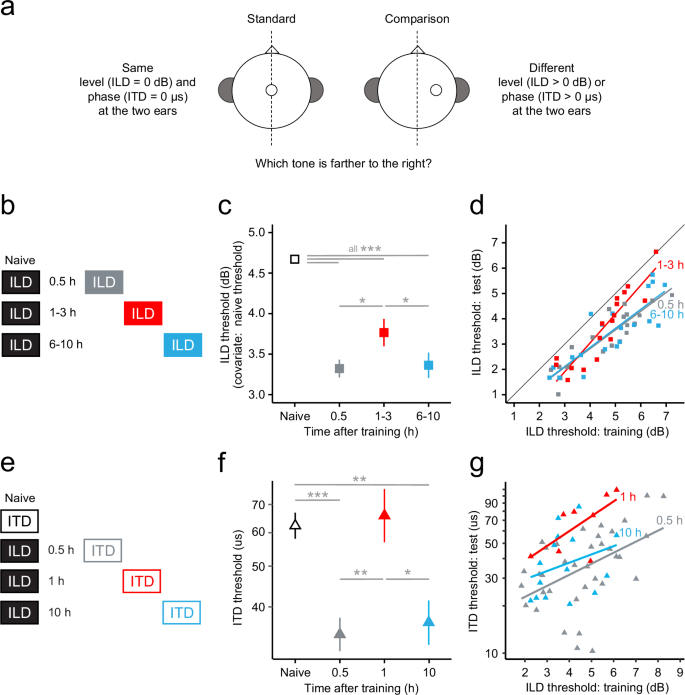

Mean improvement on both the trained task (ILD discrimination) and the untrained task (ITD discrimination) (Fig. 1a) was non-monotonic over the post-training period, with a transient memory lapse 1–3 h after training. For the trained ILD-discrimination task (Fig. 1b), performance was better after training than during training, documenting learning, at all three time points tested (Fig. 1c) (LMER bout x group: F(2,499) = 3.05, p = 0.048; simple effects: all t(499) > 5.53, all p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d (d) ≥ 0.55). However, the magnitude of improvement was greater 30 min (n = 20; improvement: 1.34 dB) and 6–10 h (n = 20; 1.34 dB) after training than 1–3 h (n = 17; 0.88 dB) after training (pair-wise comparisons of the simple effects: 30 min vs. 1–3 h: t(499) = 2.17, p = 0.047, d = 0.30; 6–10 h vs. 1–3 h: t(499) = 2.16, p = 0.047, d = 0.29). The magnitude of improvement did not differ between the 30-min and 6–10-h time points (30 min vs. 10 h: t(499) = 0.01, p = 0.989, d < 0.01). At the individual level, the transient decrease in learning magnitude 1–3 h after training was most prominent in listeners with higher initial ILD-discrimination thresholds (Fig. 1d, the closer the symbol is to the diagonal the less the learning).

a Schematic of the ILD- and ITD-discrimination tasks. b–d Learning on the trained task (ILD discrimination). b Schematics of the three regimens with testing on ILD discrimination. c Mean ILD-discrimination thresholds for naïve listeners (n = 57; open square) and for different subsets of those same listeners who were tested 30 min (n = 20; gray square), 1–3 h (n = 17; red square), or 6–10 h (n = 20; blue square) after training on ILD discrimination. Test thresholds are adjusted using the initial ILD-discrimination threshold as a covariate. d Individual ILD-discrimination thresholds from the training session (abscissa) versus the test session (ordinate) for the three trained groups (symbols as in (c); lines are best-fitting regression lines). e–g Generalization to the untrained task (ITD discrimination). e Schematics of the four regimens with testing on ITD discrimination. f Mean ITD discrimination thresholds for naïve listeners (n = 74; open triangle) and for different groups of listeners who were tested on ITD discrimination 30 min (n = 38; gray triangle), 1 h (n = 8; red triangle), or 10 h (n = 15; blue triangle) after training on ILD discrimination. g Individual ILD-discrimination thresholds from the training session (abscissa) versus ITD-discrimination thresholds from the test session (ordinate) for the three trained groups (symbols as in (f); lines are best-fitting regression lines). All thresholds are raw values. All error bars indicate ± one SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001.

Training on ILD discrimination also aided mean performance on the untrained ITD-discrimination task relative to a naïve control group, implying generalization (Fig. 1e). However, this improvement only occurred at the 30-min and 10-h time points, and not at the 1-h time point (LMER main effect of time F(3,116) = 13.021, p < 0.0001; LMER post-hoc: 30 min vs. naïve: t(128) = 5.62, p < 0.0001, d = 0.69; 10 h vs. naïve: t(129) = 3.58, p = 0.001, d = 0.62; 1 h vs. naïve: t(115) = 0.18, p = 0.85, d = 0.04) (Fig. 1f). Parallel to the trained task, the magnitude of improvement was greater 30 min and 10 h after training than 1 h after training (30 min: n = 38, improvement relative to mean naïve performance: 29.89 µs; 10 h: n = 15, 27.41 µs; 1 h: n = 8, −1.50 µs), and did not differ between the 30-min and 10-h time points (LMER post-hoc: 30 min vs. 1 h: t(116) = 3.16, p = 0.004, d = 0.73; 10 h vs. 1 h: t(118) = 2.52, p = 0.02, d = 0.66; 30 min vs. 10 h: t(128) = 0.39, p = 0.83, d = 0.07). At the individual level, for all three groups, higher thresholds on ILD discrimination during training tended to be associated with higher thresholds on ITD discrimination during testing, and the slope of that relationship was similar across the groups. Hence, the transient decrease in learning magnitude on ITD discrimination 1–3 h after training was approximately constant across the entire range of initial thresholds on ILD discrimination (Fig. 1g, the higher the ITD-discrimination threshold the less the learning). Thus, for both tested tasks, there was a transient memory lapse 1–3 h after training.

Block-by-block performance during training and testing

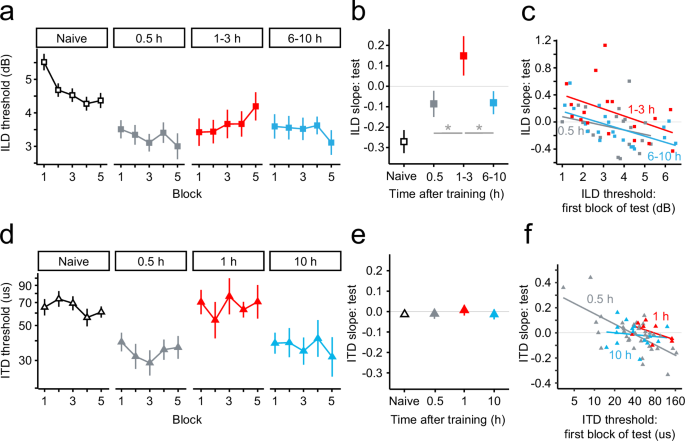

The transient memory lapse for the trained task (ILD discrimination) arose from a worsening of performance during the testing session that essentially eliminated offline learning that occurred between training and testing, but preserved within-session learning that occurred during training (Fig. 2, top row). For all three groups who were both trained and tested on ILD discrimination, performance improved equivalently during the training session itself (naïve), documenting consistent within-session learning (Fig. 2a, open squares; mean across the three groups is shown). The slopes of the individual threshold estimates over the block number were negative (indicating improvement), and did not differ across the groups (LMER block x group: F(2,54) = 0.52, p = 0.60; simple effect of block: slope < −0.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) [−0.56, −0.02], t(~53) ≥ 2.28, p ≤ 0.027; pair-wise comparison across groups: t(53) ≤ 0.98, p ≥ 0.68, d ≤ 0.08) (Fig. 2b, open square; mean across the three groups is shown). Performance also improved equivalently across the groups between the last threshold estimate in the training session and the first estimate in the testing session, showing consistent offline learning across testing times (LMER block x group: F(2,54) = 0.47, p = 0.63; simple effect of block: change ≤ −0.69, t(54) ≥ 2.16, p ≤ 0.035, d ≥ 0.43; pair-wise comparison across groups: t(54) ≤ 0.88, p ≥ 0.67, d < 0.24) (Fig. 2a, right-most open square vs. left-most gray, red, and blue squares). However, during the remainder of the testing session, performance remained constant for the 30-min and 6–10 h groups, but worsened for the 1–3 h group. The threshold slopes over blocks did not differ from zero, or from each other, for the 30-min and 6–10-h groups (LMER block x group: F(2,218) = 4.54, p = 0.012; simple effect of block: slope30min = −0.09, CI [−0.21, 0.03], t(218) = 1.46, p = 0.202; slope6-10h = −0.08, CI [–0.21, 0.04], t(219) = 1.28, p = 0.202; direct comparison: t(219) = –0.10, p = 0.92, d = 0.006) (Fig. 2b, gray and blue squares). In contrast, the slope for the 1–3 h group differed, or nearly did, from zero and was positive (indicating worsening), and differed from the slopes of the other two groups (LMER simple effect of block: slope1-3h = 0.15, CI [0.02, 0.28], t(218) = 2.33, p = 0.06; direct comparison with other two groups: t(218) ≥ 2.57, p ≤ 0.016, d > 0.16) (Fig. 2b, red squares). By the last block of testing, the mean threshold had returned to the value at the end of training for the 1–3 h group (LMER block x group: F(2,54) = 4.60, p = 0.014; simple effect of bout: change = –0.08, t(54) = 0.24, p = 0.81, d = 0.05), but remained lower (better) than at the end of training for the 30-min and 6–10 h groups (change ≥ −1.16, t(54) ≥ 3.75, p ≤ 0.001, d ≥ 0.72; direct comparisons: 1–3 h vs. 30 min and 6–10 h: t(54) ≥ 2.37, p ≤ 0.032, d > 0.67; 30 min vs. 6–10 h: t(54) = 0.53, p = 0.60, d = 0.14).

Mean thresholds by block for (a) ILD discrimination (with no covariate adjustment) and (d) ITD discrimination. Groups and symbols same as in Fig. 1c, f. Mean slopes of the individual discrimination thresholds across blocks at each testing time for (b) ILD discrimination and (e) ITD discrimination, based on the data in (a) and (d), respectively. Individual discrimination thresholds from the first block of the testing session (abscissa) for (c) ILD discrimination and (f) ITD discrimination versus the individual slopes of the thresholds across blocks from the same testing session (ordinate) for the three trained groups (lines are best-fitting regression lines), based on the data in (b) and (e), respectively. All error bars indicate ± one SEM. *p < 0.05.

At the individual level (Fig. 2c), for all three groups, the range of thresholds during the first block of testing (x axis) was similar, and higher first-block thresholds tended to be associated with more negative slopes over the testing blocks (y axis) (greater within-session learning). The clearest distinction among the groups was that there was a transient shift toward more positive slopes 1–3 h after training. That shift was of approximately equal magnitude across the entire range of thresholds on the first testing block (the higher the slope the less the within-session learning), and resulted in more slopes that were greater than zero for the 1–3-h group than for the other two groups. Thus, over the lapse period, the offline learning evident at the onset of the lapse was erased, but the within-session learning from the initial training session was maintained.

The transient memory lapse for the untrained task (ITD discrimination) manifested as uniform performance at naïve levels (Fig. 2, bottom row). All three groups who were trained on ILD discrimination but tested on ITD discrimination showed consistent within-session learning during the training on ILD discrimination. All threshold slopes were negative and did not differ across the groups (LMER block x group: F(2,58) = 0.49, p = 0.61; simple effect of block: slopes ≤ −0.24, CI [–0.71, –0.01], t (~54) ≥ 2.12, p ≤ 0.04; pair-wise comparison across groups: t (~56) ≤ 0.94, p ≥ 0.70, d ≤ 0.08) (data not shown). All three groups also showed stable within-session performance during the subsequent testing on ITD discrimination (LMER block x group: F(3,483) = 0.26, p = 0.85; simple effect of block: −0.01 < slope < 0.01, CI [−0.07, 0.08], t(~488) < 0.49, p > 0.89), like the naïve control group (slope = −0.02, CI [−0.05, 0.01], t(498) = 1.53, p = 0.51), with no difference in the threshold slope across the four groups (direct comparisons across all groups: t(~491) ≤ 0.72, p ≥ 0.83, d ≤ 0.07) (Figs. 2d and 2e). However, overall performance for the 1-h group was poorer than for the 30-min and 10-h groups, even when taking within-session performance into account (LMER direct comparison of the simple effect of group: t(~113) ≥ 2.51, p ≤ 0.02, d ≥ 0.65), and did not differ from that of the naïve control group (t(115) = 0.18, p = 0.85, d = 0.04). Overall performance did not differ between the 30-min and 10-h groups (t(128) = 0.39, p = 0.84, d = 0.07).

At the individual level (Fig. 2f), for all three groups, higher ITD-discrimination thresholds during the first block of testing (x axis) tended to be associated with more negative slopes over the testing blocks (y axis) (greater within-session learning), and the average slope was near zero. The clearest distinction among the groups was that there was a transient shift toward higher thresholds during the first block of testing 1–3 h after training. All of the individual thresholds for the 1–3-h group (x axis) were greater than the means of the 30-min and 6–10-h groups. In addition, for the 1–3-h group, there was a transient shift toward more positive slopes for any given initial threshold value. That shift was of approximately equal magnitude regardless of the initial threshold value and served to maintain the average slope near zero for the 1–3-h group despite the higher initial thresholds for that group. Thus, during the lapse period, there were no overt signs of generalization.

Discussion

The present results provide two examples of a transient memory lapse in human perceptual learning, a form of skill learning. We trained six different groups of participants on one perceptual task–interaural-level-difference (ILD) discrimination–and tested them at different time points from 30 min to 10 h after training on either the trained task, to assess learning, or on a related untrained task–interaural-time-difference (ITD) discrimination–to assess generalization. In each case, performance at 1–3 h after training was poorer than at 30 min and 6–10 h after training, documenting a transient memory lapse. The lapses cannot be attributed to adaptation or habituation arising from the multiple testing times, because we tested different groups at each time point. The lapses cannot be attributed to perceptual deterioration such as has been observed in visual perceptual learning within and across testing sessions on a single day, because that deterioration is associated with longer testing sessions than were used here (~1.5 h each vs. ~20 min each) and depends on the total amount of task performance rather than the inter-test interval39,40. The current results add to the few previous reports of transient memory lapses in humans30,31,32. The current results also add a new learning type—perceptual learning, a form of skill learning–to the list of learning types for which transient memory lapses have been documented. This addition expands the observation of transient memory lapses from learning types for which minimal training is required to induce a lasting memory to a learning type for which extensive training is required. Overall, the outcomes are consistent with the idea that transient memory lapses reflect a fundamental aspect of learning.

The transient memory lapses in human perceptual learning documented here followed two different patterns for the trained and untrained tasks, but each was similar to a pattern previously reported for other learning types in non-human species. For the trained ILD task, the lapse manifested as a worsening of performance during testing, but the learning between training and the beginning of testing showed no evidence of the lapse. This pattern is reminiscent of the lapses reported for an avoidance-learning task in rats in which relearning was slower than normal during the lapse e.g., 1,3. For both the ILD and the avoidance-learning tasks, the lapse manifested as an atypical response across repeated measures of performance during the lapse period. Of note, analyses of the relationship between the specific starting time of testing in the 1–3 h time range and the threshold slope over the testing blocks did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that the 1–3 h time range was not a transition period into a later period of steadily poor performance, but rather was the manifestation of the lapse itself. For the untrained ITD task, the lapse manifested as consistent performance at naïve levels during the testing session. This pattern is reminiscent of reports of transient memory lapses in which performance during the lapse returned to the starting value, such as for nonassociative learning and appetitive classical conditioning in sea slugs and pond snails e.g., 11,12.

The different manifestations of the transient memory lapses for the trained and untrained tasks are of particular interest because they suggest that the specific pattern that the lapse is to take is established during the testing period rather than during the training period. The different manifestations cannot be attributed to the training period, because the training was the same in both cases (300 trials of ILD discrimination). They therefore must arise at the time of testing, when the tasks differed. At that time point, it is likely that the two tested tasks—ILD and ITD discrimination—engaged different circuitry, given physiological evidence that ILDs and ITDs are initially encoded in different nuclei (for an overview, see ref. 41), and behavioral evidence, for example, of different patterns of learning42,43 and sex differences43 for ILD and ITD discrimination. If so, the different manifestations of the lapses could be due to common lapse-inducing influences that had different effects on the different circuitry, or to different lapse-inducing influences acting on the different circuitry. In either event, these data suggest that the manifestation of transient memory lapses is determined by the time of testing, rather than at the initial training. Of note, the different manifestations of the lapse for the trained and untrained tasks are consistent with other evidence that the generalization of learning from a trained to an untrained task can arise from neural changes that are, at least in part, distinct from those that govern the learning itself e.g., 44.

The present results also provide potential insight into perceptual-learning processes in humans when considered in the context of the two previously proposed explanations for transient memory lapses that were mentioned in the Introduction. According to one of those explanations, transient memory lapses reflect the incomplete temporal overlap of different forms of memory1,3,11,45. If that is the case for perceptual learning, the present results would suggest that there is a transition between different forms of perceptual memory 1–3 h after training. Moreover, given evidence that sleep is also a period of memory transition in perceptual learning46,47, including for the types of perceptual tasks employed here48, it would further appear that there are at least three memory phases in perceptual learning: one that ends ~1 h after training, a second that lasts from ~3 h after training until sleep, and a third that begins with sleep. These putative memory phases align with the phases of STM, ITM, and LTM identified in conditioning and nonassociative learning in non-human species11,20,21,22. According to the other explanation, transient memory lapses reflect failures in memory retrieval arising from a mismatch between the internal cues that are present during training and those that are present at intermediate time points after training19,27,28,29. If that is the case for perceptual learning, the present results would suggest that in perceptual learning the mismatch in the internal cues occurs 1–3 h after training. More broadly, the mere presence of transient memory lapses in perceptual learning suggests that perceptual learning, and by extension other learning types that require extensive training, may involve the same memory phases (or modulations in internal cues) and rely on the same molecular mechanisms during memory formation as other learning types that require only minimal training.

It is worth mentioning that the two highlighted explanations for transient memory lapses suggest potential alternative interpretations of retrograde learning interference—the disruption of learning by an event that occurs within a restricted time period after training. The usual interpretation of retrograde learning interference is based on the idea that newly formed memories are initially unstable, but become stabilized over time through a process of consolidation into long-term memory. Correspondingly, newly formed memories are subject to retrograde interference, but long-term memories are not. Hence the time gap between training and the interfering event at which retrograde interference ceases to occur is taken to be a marker of entry into long-term memory. However, the observation of transient memory lapses and the proposed explanations for their origins lead to potential alternative interpretations. For example, the cessation of retrograde learning interference within a few hours after training may be a marker of entry into ITM rather than LTM, or of a change in the internal cue at that time point. Along similar lines, there is some indication of a connection between transient memory lapses themselves and susceptibility to retrograde learning interference. In an investigation of associative conditioning of feeding in the pond snail, Lymnaea, retrograde learning interference occurred only when the interferers were introduced during the periods of transient memory lapses12. Thus, memory formation may be particularly vulnerable during the period of a lapse. If so, the time course of the decline of the influence of retrograde learning interferers would be nonmonotic rather than monotonic as has typically been assumed.

What role might transient memory lapses serve? One possibility is that transient memory lapses serve a direct functional role in memory formation. For example, transient memory lapses could help to maintain the balance between stability and plasticity. The nervous system faces two opposing demands: the need to maintain essential capacities (stability) and the need to modify those capacities in response to experience (plasticity). The lapses could serve as choice points between these two demands–a neural version of tapping the brakes. This idea receives some support from the evidence, mentioned above, that memory formation may be particularly vulnerable to interference during the period of a lapse12. If confirmed, the lapses would provide an opportunity to retain stability if an interfering event occurred during the lapse, or to allow plasticity if the forming LTM passed through the lapse intact. Another possibility is that transient memory lapses do not serve a direct functional role in memory formation, but rather are a marker of a key memory-formation process. For example, transient memory lapses could be a byproduct of mismatches in the offsets and onsets of different memory phases, with the different memory phases being the process that is key to memory formation.

In closing, we revisit two predictions of the proposal that transient memory lapses reflect a fundamental aspect of memory formation. The first prediction is that transient memory lapses should occur across a variety of learning types. A particularly strong version of this prediction is that the variety of learning types should encompass different memory systems. There is extensive evidence that memories of different types are stored in different memory systems that engage different neural structures e.g., 49,50. Therefore, observations that transient memory lapses occur for a range of learning types that extends across different memory systems would strengthen the idea that the lapses reflect a fundamental aspect of memory formation. Currently, nearly all of the examples of transient memory lapses are for learning types such as conditioning and non-associative learning (see Introduction) that are attributed to the nondeclarative, implicit, or nonconscious memory system e.g., 49,50. The present examples in perceptual learning are classified as nondeclarative memories as well. However, we are aware of a few examples of transient memory lapses for learning types that are attributed to a separate memory system for declarative, explicit, or conscious memories e.g., 49,50. In non-human species, the most straight-forward case is in great apes, in whom a lapse was observed ~1–8 h after training on an episodic-like memory task—remembering which of three cups hid a food reward2. In two other cases, lapses were observed: (1) in rats 8 h after training on a one-trial object recognition task, though the memory recovered after 8 h only in rats who had been injected with a memory-enhancing drug 4 min (vardenafil) or 3 h (rolipram) after training17, and (2) in mice 24 h after training on memory tasks associated with social experiences, though the lapses were only observed in phosphodiesterase 11A4 knock-out mice18. In humans, a lapse was observed on a melody-recognition task 30 min to 6 h after training on a single melody30. We also recently became aware of a transient memory lapse in humans on the recall of newly learned words 2 h after training on a set of novel word-referent pairs51. This example is of particular interest, because that investigation was not focused on transient memory lapses, and the observed lapse was discussed without reference to other examples of lapses. Yet, there was a lapse, suggesting that other examples of transient memory lapses in declarative (and non-declarative) memory may be hidden in the literature. Thus, it appears that transient memory lapses may occur within both the nondeclarative and declarative memory systems, strengthening the evidence that these lapses reflect a fundamental aspect of memory formation.

Finally, we revisit the prediction that transient memory lapses should be prevalent in human learning. If transient memory lapses reflect a fundamental aspect of memory formation, why are there so few reported cases in humans? At least four factors likely contribute to this dearth. First, to document a transient memory lapse, memory must be evaluated at a minimum of three time points after training, but testing at only one or two time points is the norm. Second, even when there is testing at three time points, the memory lapse can only be observed if the time points straddle the lapse. However, the chance of happening upon that necessary timing in unguided testing is relatively slim because the lapse kinetics are task and species dependent in non-human species (for a brief review see the discussion section in ref. 13), as well as in the few documented cases in humans. In the present and previous human cases: perceptual learning on sound-localization cues was poorer 1–3 h after training, compared to 30 min and 6–10 h after training (current data); memory for melodies was poorer from 30 min to 6 h and poorest 1 h after training, compared to 1 min and 24 h after training30; exposure-induced reduction in fear responding was poorer 24 h, compared to 50 min and 7 days, after training31; and retention of spatial working memory was poorer 20 s, compared to 0.5 and 30 s, after training32. It is worth noting, though, that most of the lapses that have been documented in mammals occurred ~1–3 h after training, including the lapse in human word learning that was documented without reference to the larger lapse literature51. Third, to identify a lapse that manifests as a worsening of performance over the course of testing requires an extended testing period, but post-training testing is frequently brief. Fourth, at least for some tasks, the lapses are only evident when the trained task is incompletely learned e.g., 5,52. Therefore, it is possible that transient memory lapses occur frequently in humans, but have been observed only rarely because the typical number, timing, and duration of post-training tests—and possibly the training protocols used–have been inadequate to reveal them.

Methods

Listeners

The listeners were 192 young adults who were tested on either ILD discrimination or ITD discrimination (see below) (ILD: n = 57, 37 females, 20 males, mean age 21.7 years, range 18–33 years, standard deviation 3.5 years; ITD: n = 135, 94 females, 41 males, mean age 21.7 years, range 18–35 years, standard deviation 3.9 years). All self-reported normal hearing and were paid for their participation. Some of the data were reported previously (see below). All procedures were approved by the Northwestern University Office for the Protection of Research Subjects (STU00030302). All listeners signed approved written informed consent forms prior to data collection.

Tasks and stimuli

There were two tasks: interaural-level-difference (ILD) discrimination and interaural-time-difference (ITD) discrimination. For both tasks, two stimuli were presented on each trial in separate observation periods. Each stimulus comprised two tones of the same frequency presented over headphones, one tone per ear, which created a sound image that was perceived as originating within the head. In one stimulus, the standard stimulus, the two tones were presented at the same level (ILD of 0 dB) and in phase (ITD of 0 µs) at the two ears. In the other stimulus, the comparison stimulus, the tone to the right ear was presented at a higher level (ΔILD) or at an earlier phase (ΔITD) than the tone to the left ear, moving the sound image toward the right. The standard and comparison stimuli were presented in random order. Listeners were asked to choose the observation period in which the sound image was further to the right (the comparison stimulus) by pressing a key on a computer keyboard. Visual feedback denoting whether the response was correct or incorrect was presented after each trial during both training and testing.

For the ILD-discrimination task, the standard and comparison stimuli were composed of 4-kHz tones presented in phase at the two ears (ITD = 0 µs). The standard differed from the comparison in that the tones were presented at the same level (70 dB SPL) to each ear for an ILD of 0 dB in the standard, and at a higher level in the right ear [70 dB+ 0.5(ΔILD)] than in the left ear [70 dB-0.5(ΔILD)] for an ILD > 0 dB in the comparison.

For the ITD-discrimination task, the standard and comparison stimuli were composed of 0.5-kHz tones presented at 70 dB SPL at the two ears (ILD = 0 dB). The standard differed from the comparison in that the tones were presented in phase at the two ears for an ITD of 0 µs in the standard, and with on ongoing phase lead in the right ear compared to the left ear for an ITD > 0 µs in the comparison.

For both tasks, the tones were 300 ms in duration with 10-ms raised-cosine rise and fall ramps. The phase of the tone to the right ear was selected at random on each trial. The inter-stimulus interval was 650 ms. The tones were delivered through a Cakewalk USB AudioCapture (Roland UA-25EX) to circumaural headphones (Sennheiser HD265) and were presented at a sampling rate of 44,100 Hz and a bit rate of 16 bits/s.

Procedure

Discrimination thresholds were estimated using a three-down-one-up adaptive procedure. The value of the ΔILD or ΔITD in the comparison stimulus was reduced after every three consecutive correct responses and was increased after each incorrect response. So called ‘reversals’ were identified as the ΔILD or ΔITD values at which the direction of the trajectory of stimulus values changed. For each block of 60 trials, the first three or four reversals were eliminated, such that the number of remaining reversals was even and was greater than or equal to four. The remaining reversal values were averaged to obtain an estimate of the ΔILD or ΔITD value necessary for 79.4% correct discriminations. For details, see ref. 43.

Training regimens

Six groups of listeners were first trained on ILD discrimination and then tested on either the trained ILD-discrimination task or the untrained ITD-discrimination task. For each test type, different groups completed the test at three different time points after the end of training: 30 min (ILD: n = 20; ITD: n = 38), 1–3 h (ILD: n = 17; ITD: n = 8), and 6–10 h (ILD: n = 20; ITD: n = 15). A seventh group was tested on ITD discrimination with no prior training (ITD naïve control: n = 74). Trained groups completed 300 training trials (5 blocks of 60 trials) and 300 testing trials. A subset of the data were reported previously, including some individual threshold values for the training bout on ILD discrimination in ILD-trained listeners43, the testing bout on ITD discrimination in naïve controls43, and the training and testing bouts in the ILD-trained/ITD-tested listeners who were tested at the 6–10 h time point48.

Before each bout, whether training or testing, listeners were given examples of the standard stimulus and of a clearly discriminable comparison stimulus.

Analyses

For the groups who were both trained and tested on ILD discrimination, we analyzed mean improvement, offline learning, offline-learning maintenance, and within-session learning. For each analysis, we conducted a separate linear mixed-effect regression (LMER) on the ILD-discrimination thresholds. For all of the analyses, group (30 min, 1–3 h, or 6–10 h) was one of the fixed factors and subject ID was a random factor. The analyses differed in the within-subject factor—the second fixed factor–and data set used. For three of the analyses, the second fixed factor was bout (training versus testing), and the data sets were as follows: (1) blocks 1–5 of training and blocks 1–5 of testing, in order to evaluate the mean improvement between training and testing, (2) block 5 of training and block 1 of testing, in order to evaluate offline learning, and (3) block 5 of training and block 5 of testing, in order to evaluate the maintenance of offline learning. For the remaining two analyses, the second fixed factor was block, and the data set was blocks 1–5 in (4) training or (5) testing, in order to evaluate the slope of within-session learning. For each analysis, we report the bout x group interaction (ILD-tested groups), the main effect of time (ITD-tested groups), or the block x group interaction, as appropriate. We also report the simple effect of bout (or the regression coefficient for block, for within-session learning) for each group to show the improvement of each group, and the pair-wise comparisons among groups.

For the groups who were trained on ILD discrimination and tested on ITD discrimination, we analyzed the mean improvement on ITD discrimination (relative to naïve controls), and within-session learning during training and testing. We performed all analyses of the ITD-discrimination thresholds on the ITD thresholds in logarithmic units [10 log 10 (ITD in μs), where ITD is the threshold value in μs]. Where feasible in reporting, the logarithmic values are converted back to the more familiar units of raw μs. To examine the mean improvement on ITD discrimination, we conducted LMER on the ITD-discrimination thresholds, with group (naïve, 30 min, 1–3 h, or 6–10 h) as the fixed factor and subject ID as the random factor. We report the pair-wise comparisons on the ITD thresholds between the naïve group and the ILD-trained groups to represent the mean improvement of each ILD-trained group on ITD discrimination, and the pair-wise comparison among the ILD-trained groups. We analyzed the within-session learning–during training on ILD discrimination and during testing on ITD discrimination—using the approach described above.

All tests were two-tailed. The p values for the simple effects and pair-wise comparisons were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (FDR) method. For the simple effects that involved either mean comparisons or pair-wise comparisons, we report Cohen’s d, computed as the mean difference divided by the sum of the residual sigma and random-effect sigma. For simple effects that involved slopes we report the raw 95% confidence interval.

Note that all of the data of three listeners in the ITD-tested groups were omitted from the analyses because each listener had a threshold that was outside 1.5 times the interquartile range above the upper quartile of all ITD-tested listeners. For two listeners, the outlying threshold was the mean ILD-discrimination threshold during training (30-min group and 10-h group). For the other listener, the outlying threshold was the mean log-transformed ITD-discrimination threshold during testing (ITD-naïve control group). Those three listeners were not included in the total listener count (n = 192).

For each LMER analysis, we fitted two models with different random effects: a simpler model and a more complex model. In the simpler model, we included the random effects of intercept caused by the random factor (subject ID). In the more complex model, we included both the random effects of intercept caused by the random factor (subject ID) and the random effects of slope caused by the interaction between the random factor (subject ID) and the within-subject fixed factor (bout or block). The more complex model was not viable in four cases: in two cases there were too few observations for the computation (offline learning and maintenance of offline learning for testing on ILD discrimination) and in the other two cases the model failed to converge (mean improvement and within-session learning during testing on ITD discrimination), so we report the simpler model for these analyses. In each of the other cases, we compared the two models using ANOVA, and reported the simpler model unless the more complex model fitted significantly better than the simple model. The simple model was selected for two cases (mean improvement and within-session learning during testing on ILD discrimination) and the more complex model was selected for two cases (within-session learning during training on ILD discrimination for both the ILD- and ITD-tested groups).

Responses