A translational framework of genoproteomic studies for cardiovascular drug discovery

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), predominantly by ischemic heart disease and stroke, is the leading cause of death globally, contributing to approximately one-third of all deaths1. Public health advances in lifestyle and pharmaceutical intervention (e.g., HMGCR2 and PCSK9 inhibitors lowering the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C] level3) have been reported to avert up to 80% of premature cardiovascular conditions4. Nevertheless, the drug development for CVD has encountered stagnation in recent decades5, primarily attributed to the lack of clinical efficacy (40%~50%) and safety (~30%)6,7,8. Such a predicament has resulted in a successful rate of <10% for drug development, even after more than a decade of extensive investigation8. Of these, targeting non-causal biomarkers and unintended effects on causal biomarkers are the main reasons for the insufficient efficacy and unmanageable side effects. Consequently, a compelling call to act for innovative global approaches to CVD drug solutions was articulated in 20219.

The availability of genetic associations from large-scale biobanks, such as the UK Biobank10, deCODE Genetics11, Biobank of Japan12, China Kadoorie Biobank13, FinnGen in Finland14, Lifelines in the Netherlands15, the Million Veteran Program16, and the All of Us Research Program17, alongside advances in post-GWAS (i.e., genome-wide association study) analytical techniques (e.g., Mendelian randomization [MR]18 and colocalization19), presents multiple opportunities20,21,22,23,24, such as (1) unraveling the biological mechanisms underpinning the disease causality and identifying risk factors that are causal and pharmaceutically modifiable by manipulating a drug protein target, thereby addressing the non-causal protein targets; (2) discerning the potential side effects and identifying the drug-sensitivity population to mitigate the off-target effect; (3) determining the timing of drug interventions; and (4) predicting the long-term consequences of pharmacological intervention, aiding the drug development. More importantly, drug targets supported by human genetic evidence exhibit a more than 2-fold excess chance of being approved25,26 and boost a short drug-discovery life cycle27. For instance, in 2021, two-thirds of the US FDA-approved drugs were supported by human genetic evidence involving either gene-encoding protein targets or closely related proteins28.

Nevertheless, translating GWAS findings into clinical applications remains challenging, as over 90% of GWAS hits reside in non-coding regions of the genome, solely influencing disease susceptibility or progression29. Consequently, these variants’ functional and clinical consequences on putative drug-targeting proteins remain to be discovered30,31. One promising avenue for unraveling gene-protein-disease mechanisms is the integration of human genetics and high-throughput proteomics (i.e., genoproteomic). This approach facilitates the disentanglement of complex relationships and provides insights into shared genetic architecture across diseases within a translational framework for drug discovery24,32,33, particularly genetic loci situated within or near protein-encoding regions involving cis-acting variants that impact the expression of associated proteins directly. Moreover, circulating proteins in human blood, annotated and potentially predicted by protein-coding genes in the human genome, reflect an individual’s dynamic health status and candidate drug targets manipulated by small molecular entities, peptides, or monoclonal antibodies33,34. A telling example of such translational approaches is LDL-C-lowering drugs encoded by the PCSK9 gene35,36.

This article emphasizes the translational application of genoproteomic data in drug discovery, emphasizing rigorous efforts to address the prevalent challenges of insufficient efficacy and safety. First, we present an analytical, translational framework for cardiovascular drug discovery and validation, which incorporates various Mendelian randomization (MR) methods coupled with several complementary genetic analyses. Then, we illustrate the translational framework by replicating those currently in developed lipid-lowering drug targets encoded by apolipoprotein B (apoB)-containing lipoproteins-lowering APOB variants37, LDL-C-lowering LDLR variants37, and lipoprotein(a)-lowering LPA variants38, along with some general recommendations. We conclude with an in-depth discussion of challenges and remarks on further directions. Herein, we focus on cardiovascular drug discovery, mainly due to the emerging publicly available biobank-scale genetic estimates with sufficient cardiovascular events. Undoubtedly, we can easily extend this translational framework to other diseases.

Results

Translational framework of genome-proteome-phenome for drug discovery

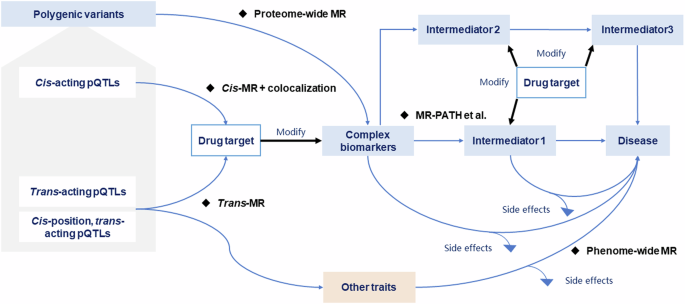

The presented translational framework integrates the genome, proteome, and phenome in the context of drug discovery by synergistically exploring the interplay between genetic variants, protein levels, and health outcomes using a series of MR analyses and genetic and observational analyses. This framework consists of four stages, as illustrated in Fig. 1, providing a pipeline to bridge the gap between genetic variants and tangible clinical outcomes and facilitating drug discovery.

Scheme of the translational framework for drug discovery. MR Mendelian randomization.

Stage 1. Causal biomarkers screen

This stage involves a proteome-wide MR (i.e., ProMR) analysis, a hypothesis-free design, to pinpoint promising biomarkers causally associated with the health outcome of interest by systematically screening the proteome at a broad scale. We mimicked the downstream effects (i.e., MR estimates, Fig. 2) of candidate biomarkers using genetic variants from large-scale GWAS as instrumental variables (IVs) on health outcomes. Herein, we distinguished biomarkers from drug-targeting proteins, as the former often encapsulates a complex phenotype or a collective trait that objectively reflects the biological processes. In contrast, the latter represents a target capable of modifying the complex phenotype through specific biological mechanisms by appropriate drugs, as extensively discussed in work by Holmes et al.22. For instance, biomarkers like LDL-C are well-recognized to be associated with cardiovascular risk, whilst lowering LDL-C typically via specific drug-target proteins such as statins2 and PCSK93 inhibitors.

Principles of Mendelian randomization. IVs instrumental variables.

However, considering the mimicked effects derived from genetic estimates exhibited variability and differed from those obtained from randomized controlled trials (RCTs)39,40, the IVs used in this stage are not restricted to the independent cis-acting variants near or within the protein-coding regions, as illustrated in Fig. 3. In contrast, using IVs at genome-wide significance (p < 5 × 10−8)41 or at a less stringent significant level (p < 1 × 10−5)21,42 would enhance the power of ProMR as a screening tool. This is particularly useful when only a limited number of IVs are available for the biomarker or when the number of diseases under consideration is small.

Cis-acting variants, located within or near the protein-coding gene, directly influence the expression and function of the drug-targeting protein. In contrast, trans-acting variants (including cis-position, trans-acting variants), resided apart from the protein-coding gene, exert indirect effects, influencing the protein’s expression and function through processes such as RNA-level transcription and translation, post-translational modifications, and protein-protein interactions.

Furthermore, given the inherently low prior probability of causality between a biomarker and a health outcome5,6,7,8, the challenge in this stage lies in how to balance false positive and false negative results from ProMR, which determines the risk of advancing insufficient drug-targeting proteins or overlooks promising drug candidates in late-phase clinical trials21,42. To address this problem, we employed a fully automatically estimated q-value (i.e., the probability of a null feature being as or more extreme than the observed one) to control the false discovery rate — the expected proportion of how many screened significant biomarkers that are truly null43,44,45. Unlike the false positive rate quantifying the expected proportion of null exposure-outcome associations deemed significant, a q-value provides a more clinically meaningful measure. This is particularly relevant for significant biomarkers undergoing subsequent biological verification in the ensuing stage43.

Nonetheless, screening the most plausible, or at the very least, statistically robust biomarkers for the health outcome of interest is paramount in cardiovascular drug discovery. This initial step provides crucial evidence indicating that modifying the biomarker can alter the disease’s risk, laying the foundation for subsequent stages of the translational framework.

Stage 2. Drug-targeting protein discovery and verification

In Stage 2, we delve into genetic analyses to discern the specific biological mechanisms through which identified causal biomarkers influence disease risk, pinpointing the potential drug-targeting proteins that serve as critical modulators within the relevant pathways.

Though the replication of screened biomarkers in Stage 1 using large samples provides a more straightforward approach to triangulating the robust and consistent biomarker-outcome associations, understanding the underlying downstream biological mechanisms from the biomarker to the health outcome through various genetic analyses is crucial for prioritizing and identifying the putative drug targets. To achieve this, several genetic analyses are employed:

-

(1)

Elucidation of possible heterogeneous genetic effects oriented by polygenic IVs across the genome for the biomarker, utilizing methodologies such as Genome-wide mR Analysis under Pervasive PLEitropy (GRAPPLE)46 and MR-PATH47.

This involves determining upstream regulators or downstream intermediates as putative drug targets. Considering the highly polygenic nature of the complex biomarkers, large-scale GWASs typically identify the associated significant loci across the genome. Further disentangling the underlying biological mechanisms captured by polygenic IVs-oriented heterogeneous effects can help underpin the potential drug targets46,48. For example, body mass index (BMI), a polygenic biomarker, has been implicated in the risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and coronary heart disease (CHD), as demonstrated in RCTs and MR49,50. One plausible pathogenic mechanism from BMI to CHD involves altering the blood glucose levels50,51. As such, SGLT1 associated with altered blood glucose levels is expected to influence the risk of obesity and vascular disease52. However, genetically mimicking the therapeutic inhibitor of SGLT2 encoding by the SLC5A2 gene on vascular disease remains challenging53,54.

-

(2)

Exploration of the putative protein-disease association using cis-acting protein quantitative trait loci (cis-pQTL) as IVs, supplemented by the inclusion of trans-acting variants and cis-position, trans-acting variants, as appropriate34.

The human plasma proteome is comprehensively defined through the analysis and annotation of all potentially protein-coding genes in the human genome33, providing a blueprint for the expression and processing of drug-targeting proteins. In GWAS, genetic variants associated with the protein level at genome-wide significance are termed “protein quantitative trait loci (QTLs)”. They are often represented by the most strongly associated single-nucleotide polymorphism. Typically, pQTLs at or near the protein-coding genes in the genome (i.e., cis-pQTLs) can directly influence the expression or turnover of the associated protein. In contrast, pQTLs located distinct from the protein-coding gene or on other chromosomes (i.e., trans-pQTLs) often exert their influence on the related protein through various indirect processes, such as directly regulating the protein’s transcription-to-translation at the RNA level33, as depicted in Fig. 3. Thus, replicating the putative protein-outcome association using cis-pQTLs would enhance the credibility of the protein as a drug target22,23. For instance, genetic variants within the CEPT gene (Chr 16: bp: 56,961,923-56,985,845; GRCh3855) have been previously employed to mimic the therapeutic effect of CEPT inhibitors, illustrating the apoB-mediated effect on CHD rather than an HDL cholesterol-mediated effect56,57.

Moreover, incorporating trans-pQTLs that influence the related proteins via various indirect processes may also help improve the statistical power when only a few cis-pQTLs are available and broaden our understanding of the biological implications of the drug-targeting proteins. For instance, recent studies from the UK Biobank Pharma Proteomics Project (UKB-PPP)24 show that including trans-acting loci into 861 proteins exhibits 1.16 times more detected significant signals than the permuted background.

-

(3)

Verification of putative drug-targeting proteins by examining whether the cis-acting variants are shared with the same causal variants as the upstream regulators or downstream intermediates, utilizing colocalization58,59 based on gene expression database (e.g., GTEx V860 and eQTLGen61) or conducting cell and animal experiments.

Despite substantial progress in studying protein characteristics, translated proteins often undergo complex post-translational processes, leading to their functional exertion through interactions with other proteins62. For example, the association of tissue-specific regulatory variants and expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) with the health outcome emphasizes the importance of identifying colocalized cis-pQTLs that regulate the expression of the associated proteins. Changing the genotypes at this position leads to alternations in the downstream proteins rather than the variants that tend to be physically inherited together (i.e., linkage disequilibrium in which non-causal variants are physically closely correlated with causal variants). Hence, it is crucial to validate putative drug targets by examining whether cis-pQTLs are shared with the same causal variants as the upstream regulators or downstream intermediates.

This process is essential for reinforcing the validity of the drug-targeting proteins, though the highly likely colocalization rate (i.e., posterior probability≥0.8) of pQTLs with a disease- or phenotype-related locus was relatively small, ranging from 7.3% to 40%63,64,65, depending on the plasma proteomics and genomics technologies and sample size. Moreover, designing and conducting experimental studies (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9) may enhance the biological implications of intervening in drug-targeting proteins.

Stage 3. Drug target relevant side effects exploration

In Stage 3, a phenome-wide MR (PheMR) is employed to investigate the potential side effects of the drug-targeting protein. This critical step aims to comprehensively assess the impact of modifying the protein of interest on a wide range of health outcomes, elucidating the possible unintended consequences and safety profiling, thereby guiding the decision-making process before advancing to late-phase clinical trials.

An illustrative example is found in a recent MR study on ASGR1 inhibitors, where PheMR was employed to investigate the suspected side effects, showing that genetically mimicked ASGR1 inhibitors not only reduced all-cause mortality but increased the risk of liver dysfunction, cholelithiasis, adiposity, and type 2 diabetes66. A similar study design was also utilized to evaluate the safety profiling of lipid-modifying medications in Chinese adolescents67.

Stage 4. Therapeutic efficacy and safety emulation

This stage involves implementing a hypothetically randomized controlled trial (i.e., target trial emulation68,69 or pragmatic trials70,71) to assess the impact of an intervention, providing a rigorous evaluation of the anticipated benefits and potential risks associated with the drug-targeting protein. Specifically, a hypothetically randomized controlled trial is comparative effectiveness research using big data or large observational databases to emulate a randomized experiment that would answer the specific clinical question of interest when randomized trials are not available68.

In contrast to the conventional observational studies, which are susceptible to confounding, selection bias, and reverse causality, the emulation of target trials using available observational data, coupled with appropriate analytical methods, allows for evaluating the benefit-to-risk of the drug-targeting protein69,72,73. This can be achieved rigorously by mimicking eligibility criteria, treatment strategies, assignment procedures, outcomes, follow-up, causal contrasts of interest, and statistical methods aligned with the target RCTs. A particularly telling example is the emulation of messenger RNA-based vaccines for preventing COVID-1974,75,76, complemented by large-scale RCTs77.

Furthermore, utilizing different study designs susceptible to various bias sources would aid in triangulating the findings from earlier stages, ensuring the observed effects on efficacy and safety of the drug-targeting protein are consistent and replicable78,79. Therefore, this stage is pivotal in translating genetic and proteomic findings into actionable evidence. Finally, Table 1 summarizes the key ideas of the methodologies involved in the proposed translational framework.

An applied example and some implementing recommendations

To illustrate, we applied the proposed translational framework to replicate the promising lipid-lowering therapeutic targets encoded by APOB (triglyceride- and LDL-C-lowering37), LDLR (LDL-C-lowering37), and LPA (Lp(a)-lowering38) loci to prevent coronary artery disease (CAD) that have been validated in ongoing clinical trials80,81,82. Herein, we focused on genetically mimicked LDL-C-lowering pathways encoded by APOB, LDLR, and LPA loci. Specifically, we used publicly available GWAS summary-level statistics of LDL-C from the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium (GCLC, 1,654,960 individuals)83, of CAD from the CARDIoGRAMplusC4D Consortium (60,801 cases and 123,504 controls)84, and the 29-year longitudinal data (5735 individuals) from the Chinese Multi-provincial Cohort Study85,86. We aligned the effect alleles of variants within APOB, LDLR, and LPA loci as risk-increasing alleles to facilitate the implementation of the proposed framework. More details are presented in the Method section, with the reproducible codes available at https://yangzhao98.github.io/drugTargetScreen/articles/Codes_for_Paper_1.html.

Stage 1. Causal biomarkers screen

As positive control examples, we first assessed associations of genetically predicted LDL-C proxied by genome-wide significant SNPs with linkage-disequilibrium (LD) clumped at an r2 < 0.3 with CAD using inverse-variance weighting two-sample MR estimate with random effects. Like the conventional MR87, we exclusively focus on these independent IVs at genome-wide significance without known horizontal pleiotropy via the curated and cross-referenced database of PhenoScanner V288,89 to minimize pleiotropic effects and avoid biased MR estimates.

To further ensure the reliability of the selected IVs, we insist on IVs with replication across different studies. We specifically categorized the selected GWAS hits into the following subgroups, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

-

a.

Cis-pQTLs: Genetic variants reside within or near the protein-coding region in the human genome (e.g., ±10kbp) with the lowest p-value;

-

b.

Trans-pQTLs: Genetic variants distinct from the protein-coding region reside in other parts of the human genome;

-

c.

Cis-position and trans-acting pQTLs: A subset of trans-pQTL located within 1 Mb of the protein-coding region in the human genome.

Based on the stage-specific purposes of the proposed translational framework, we also provided some practical recommendations for choosing genetic variants as IVs, as summarized in Fig. 4.

Implementation recommendations of protein quantitative trait loci (pQTLs) as instrumental variables for Mendelian randomization (MR).

Thus, in this stage, the polygenic variants, including cis-, trans-, and cis-position and trans-acting pQTLs, were used to screen potential causal biomarkers. We found that genetically mimicked LDL-C per standard deviation (SD) increase was associated with an increased CAD risk (odd ratio [OR] = 1.64; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.58–1.70, p = 4.51 × 10−145), as depicted in Fig. 5-1a, suggesting its capability as a candidate drug target for lowering CAD risk.

1a The scatter plot of genetic effects on LDL-C and CAD using all available genetic variants at genome-wide significance across the genome. 2a The scatter plot of genetic effects on LDL-C and CAD using all available variants within or near either APOB, LDLR, or LPA loci as instrumental variables (IVs). 2b The possible pleiotropic effects detected using Genome-wide mR Analysis under Pervasive PLEitropy (GRAPPLE). 2c Forest plot of the genetically mimicked LDL-C-lowering effects driven by APOB, LDLR, and LPA loci on CAD using cis-pQTLs or fine-mapped variants as IVs in Mendelian randomization analyses. 2d–f: Regional plots of colocalization analyses for APOB, LDLR, LPA loci, and expression quantitative trait loci from eQTLGen phase 1 and CAD. 3a–c Volcano plots of the potential side effects of LDL-C-lowering driven by APOB, LDLR, and LPA loci. 4a The observed and g-formula estimated cumulative atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk based on the Chinese Multi-provincial Cohort Study participants. 4b–d: The estimated cumulative ASCVD, CVD, and all-cause mortality risk with or without hypothetical interventions on lowering LDL-C by modifying APOB, LDLR, and LPA.

Stage 2. Drug-targeting protein discovery and verification

Based on the online resource of Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor90, supplemented by Genome Aggregation Database91 and Functional Annotation of Variants92, we limited variants from protein-coding genes of APOB (Chr2:21224301-21266945, GRCh37), LDLR (Chr19:11200038-11244492), and LPA (Chr6:160952515-161087407) to mimic lipid modifying agents. In such a case, genetically mimicked LDL-C per SD increase was associated with an 80% increased CAD risk (OR=1.80, 95% CI: 1.47–2.21, p = 1.36 × 10−8, Fig. 5-2a).

-

(1)

Elucidation of possible heterogeneous genetic effects on LDL-C

We first explored heterogeneous genetic effects (i.e., pleiotropic effects) of these selected variants from protein-coding genes associated with LDL-C levels. Then, we identified possible pleiotropic patterns using GRAPPLE46 under a three-sample MR framework, with GWAS summary statistics of LDL-C from GCLC as the selection cohort and those from UK Biobank (343,621 individuals, http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank/) as the exposure cohort. We noted multiple possible pleiotropy pathways in the effect of LDL-C with diverging causal directions, as shown in Fig. 5-2b. These suggest different biological mechanisms underlying three candidate druggable targets.

-

(2)

Exploration of cis-pQTLs-based LDL-C-CAD associations

We annotated the selected SNPs with Ensembl version 110 (GRCh37). Then, we performed fine-mapping analysis for each gene using the “Sum of Single Effects (SuSiE)” model93 to identify a credible set of genetic variants that causally affect LDL-C levels. We termed the druggable SNPs in or near (±10 kbp) region around each gene as cis-pQTLs, with others as trans-pQTLs. Herein, we didn’t consider the cis-position and trans-acting variants for simplicity. As expected, genetically mimicked LDL-C per SD increase driven by APOB (OR = 1.64; 95% CI: 1.31–2.04, p = 1.46 × 10−5), LDLR (OR = 2.13; 95% CI: 1.80-2.53, p = 3.68 × 10−18), and LPA (OR = 10.0; 95% CI: 8.02-12.45, p = 1.71 × 10−93) were associated with increased CAD risks (Fig. 5-2c), validating the druggable targets for preventing CAD by lowering LDL-C levels.

-

(3)

Verification of LDL-C-CAD associations with additional use of eQTLs

We further conducted multi-trait colocalization analyses94 using a Bayesian divisive clustering algorithm to verify whether the candidate causal SNPs within or near (±10 kbp) each druggable gene associated with downstream expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs, with summary-level statistics from the eQTLGen Consortium)61 and CAD. The genetic effects on LDL-C levels, eQTLs, and CAD were driven by the same causal variants within/near each gene, as depicted in Fig. 5-2d–f.

Moreover, for the trans-pQTLs, including cis-position and trans-acting pQTLs, exploratory analyses are encouraged to unravel potential post-translational modifications, protein-protein interaction networks, or biological pathways involving the drug-targeting protein and other proteins (Fig. 3), alongside the use of additional data with specific molecular phenotypes (e.g., RNA expression and eQTL database60,61 with annotated pathway database, e.g., Reactome95). For instance, the multi-trait colocalization analyses suggest potential post-translational modifications and protein-protein interactions (Fig. 5-2d–e). Such results emphasize the importance of complementary evidence from trans-acting loci for providing additional insights into the biological process involving the drug-target protein.

Stage 3. Drug target relevant side effects exploration

Unlike the cis-pQTLs used in Stage 2, we implemented hypotheses-free analyses using polygenic variants-based phenome-wide MR for 78 clinical endpoints with ICD-10 diagnoses in UK Biobank (excluding coronary artery disease with ICD-10 code of I25) to explore the potential side effects of the candidate drug targets. There were no significant side effects after controlling the false discovery rate at the 5% level, as depicted in Fig. 5-3a–c. However, such results should be carefully interpreted since we couldn’t exclusively exclude all side effects beyond these 78 identified clinical endpoints.

Stage 4. Therapeutic efficacy and safety emulation

Finally, we emulated hypothetical target trials to investigate the preventive effects of mimicking the LDL-C-lowering intervention with the candidate drug targets on atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), CVD, and all-cause mortality risk using the 29-year longitudinal study of the Chinese Multi-provincial Cohort Study85,86. We found that per 1 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C levels appeared to reduce atherosclerotic CVD risk by 19% (OR = 0.81; 95% CI: 0.65–0.99) among participants with baseline LDL-C ≥ 1.8 mmol/L, consistent with the well-established benefit of approximate one-fifth CVD risk reduction in statins trials2. Similar effects were also noted for 40% of LDL-C reduction that mimicked the statins therapies compared with the baseline LDL-C by hypothetically modifying APOB, LDLR, and LPA loci, as depicted in Fig. 5-4a–d.

Discussion

Despite the notable advances in MR and complementary genetic analyses19, which have emerged as powerful tools for cardiovascular drug discovery, challenges persist in applying them to mitigate the insufficient drug safety concerns6,7,8. Previous discussions have extensively covered the potential of these methodologies20,22,23, but a consensus on their optimal application to address failures in cardiovascular drug development is yet to be reached. Given the current landscape of genetic-oriented multi-omics studies, with a notable influx of proteomic studies, as documented in http://www.metabolomix.com/a-table-of-all-published-gwas-with-proteomics/, we have centered our efforts on developing this genome-proteome-phenome translational framework. This integrative framework is designed to serve as a pipeline to offer a practical approach to tackle insufficient and unsafety concerns through various post-GWAS analyses of the drug target in late-phase clinical trials. This framework is further reinforced by emulating randomized hypothetical target trials.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge the persisting challenges in this field that require ongoing attention and exploration. The translational framework outlined here heavily relies on MR and, consequently, inherits its limitations in application96,97 and interpretation39,40. For instance, when evaluating the efficacy and safety of the therapeutic interventions for the drug-targeting protein in clinical practice, MR estimates quantify the life-long effects of the drug-target protein on diseases, which may not accurately capture the short-term therapeutic effect of medication40. Additionally, considering that GWAS are often conducted in middle-aged and healthy participants (e.g., UK Biobank10, Biobank of Japan12, and China Kadoorie Biobank13), the genetic associations for the causal biomarkers or the drug-targeting protein are typically biased towards the null, making MR estimates open to selection bias98,99. While careful selection of genetic variants as IVs with appropriate analytical methods can mitigate such bias. More importantly, IVs chosen from a middle-aged or older population may differ from those relevant to patients with the disease of interest. Consequently, the identified drug targets may be more pertinent to the onset of the disease rather than its progression among patients. To address this issue, replication of the identified drug target in representative samples of patients, incorporating advanced MR techniques like multivariable MR100, becomes imperative. This ensures a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the translational implications in the clinical practice.

Another challenge arises from the distribution of proteins within the human body, as presented by the Human Protein Atlas (HPA)101. Over two-thirds of proteins reside intracellularly, approximately 28% are membrane-bounded, and ~9% are secreted into the extracellular space. As such, current protein profiling from blood samples may fail to capture crucial intracellular signals64, masking potential pleiotropic effects and contributing to failures in drug development, especially concerning efficacy issues. Moreover, current protein-detection techniques, such as Olink and SomaScan, are based on the affinity of the proteins binding to expected targets, only capturing ~30% of proteins encoded in the human genome65 based on whole blood samples. Further integrative research combining cutting-edge protein-detection technologies and disease-specific tissues may broaden the spectrum of captured proteins, providing a more comprehensive foundation for drug discovery.

Finally, over 90% of GWAS hits map to the regulation of the associated proteins in non-coding regions of the human genome102, primarily due to LD. Typically, LD complicates direct biological and causal inference103, yielding unclear downstream effects and challenging the subsequent variant-to-function annotation process104. As a result, the selected IVs may fail to effectively mimic the therapeutic effects of the drug target, violating the gene-environment equivalence assumption—the genetic effect from IVs is qualitatively equivalent to the proposed intervention of the drug target23. Thus, based on observed patterns of LD and genetic estimates, using statistical fine-mapping (e.g., FINEMAP105, CAVIAR106, and SuSiE17,18) or polygenic priority score107 to prioritize the most credible causal variants contributing to disease development within or near the protein-coding gene provides a helpful approach.

Nevertheless, the intricate regulatory downstream network or pathway effects of the non-coding GWAS hits, for instance, post-translational modifications of the drug target occurring at stages of transcription and translation, make the biological implication not easily to be inferred65. Thus, identifying regulatory or coregulation pathways of the GWAS hits via cis- or trans-eQTL analysis based on multiple tissue- and cell-level molecular data or functional genomic data may advance their role in regulating network effects contributing to disease development41. However, compared to biobank-scale GWAS studies, the sample size of these tissue-specific studies was typically small, limiting their statistical power for detecting significant eQTLs. In such contexts, complementary experimental studies using advanced approaches, such as CRISPR screening in cellular or animal models108, provide another practical approach to advancing biological interpretation and drug discovery.

In conclusion, the wealth of large-scale genetic and proteomic data will empower the genome-proteome-phenome translational framework proposed here as a helpful pipeline for cardiovascular drug discovery. Though positive findings from this translational framework do not guarantee the success of drug development, it establishes a practical pipeline and an unprecedented opportunity for drug target screening. We envision this translational framework as a promising starting point for integrating multi-omics to facilitate drug discovery and guide further research toward more effective and safer cardiovascular therapeutics in clinical practice.

Methods

To illustrate how the proposed translational framework can help prioritize drug targets and accelerate the drug development process, we provided a step-by-step applied example to replicate the promising therapeutic targets of LDL-C encoded by APOB37, LDLR37, and LPA38 loci.

Data sources

GWAS summary statistics of LDL-C

We extracted genetic variants from the aggregated GWAS results from the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium, which included 1,654,960 individuals with an average age of 55 from 201 primary studies, including 99,432 admixed African or African, 146,492 East Asian, 1,320,016 European, 48,057 Hispanic, and 40,963 South Asian participants83 as instrumental variables in Mendelian randomization. For each cohort, a standard GWAS protocol (https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.pex-1687/v1) was used to perform imputation, quality control, and GWAS analysis of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) with adjustment of age, age2, sex, and principal components (PCs) of ancestry. Then, ancestry-specific meta-analyses of LDL-C were performed.

GWAS summary statistics of CAD

Meta-analyzed 1000 Genomes-based GWAS results of mainly European (77%), South Asian (India and Pakistan, 13%), and East Asian (China and Korea, 6%) for coronary artery disease (CAD, including 60,801 CAD cases and 123,504 controls) were used84. Briefly, minor and major alleles of each contributed GWAS study were identified and imputed by reference to allele frequencies in the pooled populations (all continents) of 1000 Genomes Project phase 1 v3 data. Genetic associations were assessed by the genomic control method, with the overdispersion tissue being adjusted in the inverse variance-weighted fixed-effects meta-analysis. We obtained the aggregated genetic associations for CAD in the applied example.

GWAS summary statistics of 78 clinical endpoints in UK Biobank

The UK Biobank recruited approximately 500,000 individuals aged 40–69 years, with 45.6% of men and 94% being self-reported European ancestry from 2006 to 2010 across the United Kingdom10. At recruitment, socio-demographic, lifestyle, and health-related factors were collected using questionnaires for all participants after obtaining informed consent. Moreover, biological samples, such as blood, urine, and saliva, were also collected during physical examinations. With these samples, various assays were further examined (e.g., genetic, proteomic, and metabonomic analyses). Follow-up outcomes were obtained from nationwide electronic medical and mortality records. The whole genome-wide analyses of 7221 phenotypes across 6 continental ancestry groups in UK Biobank were conducted by Neale lab (https://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank) among 361,194 participants (194,174 females and 167,020 males) of British ancestry, with the corresponding genetic estimates adjusting for age, age2, inferred sex, age * inferred sex, age2 * inferred sex, and the first 20 principal components in sex-combined analyses.

Summary statistics of cis- and trans-eQTLs

We obtained summary statistics of cis– and trans-expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) from the eQTLGen Consortium, in which 21,684 individuals with 31,684 blood (80.4%) and PBMC (19.6%) samples from 37 datasets were used to detect trait-associated SNPs61. Each cohort analyst preprocessed, standardized, and analyzed each contributed data, including genotype expression data preprocessing, PGS calculation and cis-eQTL, trans-eQTL, and eQTLs mapping. Then, these results from each dataset were meta-analyzed using a weighted Z-score method.

Chinese Multi-provincial Cohort Study

The Chinese Multi-provincial Cohort Study (CMCS) is an ongoing longitudinal study in China, which recruited 21,953 participants from multi provinces in China during 1992–1993 (16,811), 1996–1999 (3129), and 2004–2005 (2013)85,86. Demographics, lifestyle, and physical characteristics of all participants were collected using a standardized questionnaire modified based on the WHO-MONICA protocol after obtaining informed consent, with clinical measurements being tested in the laboratory using overnight blood samples. All participants were actively followed up for the onset of all fatal and non-fatal acute coronary and stroke events or deaths every 1 to 2 years, supplemented via the local disease surveillance systems. Of these participants, up to 5735 CMCS participants aged 35 years or above were actively invited to participate in the in-person follow-up surveys in 2002, 2007, and 2012, and 2020–2023. Moreover, the ASCVD events were defined as acute coronary (including acute myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, and chronic coronary death) and ischemic stroke events. CVD events were diagnosed based on the criteria of the WHO-MONOCIA project before 2003 and were modified after 2003 following advances in diagnostic technology for myocardial infarction.

Statistical analyses

Briefly, we selected single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at the genome-wide significance of 5 × 10−8) with linkage disequilibrium at an r2 < 0.3 as instrumental variables for LDL-C from the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium https://csg.sph.umich.edu/willer/public/glgc-lipids2021/). We annotated the selected SNPs with Ensembl version 110 (GRCh 37, https://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/grch37/release-110/gff3/homo_sapiens/). We then performed fine-mapping analysis for each gene with the “Sum of Single Effects (SuSiE)” models to identify a credible set of genetic variants that causally affect LDL-C levels. Within the credible set, we termed those within or near (±10 kbp) protein-coding region around each gene as cis-acting variants and those far away from the gene as trans-acting variants. Herein, we didn’t consider those cis-position and trans-acting variants for simplicity. Moreover, genetic estimates from the UK Biobank (https://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank) were employed as the exposure cohort in Genome-wide mR Analysis under Pervasive PLEitropy (GRAPPLE)46 in a three-sample MR setting.

Based on the selected SNPs, we obtained MR estimates by meta-analyzing Wald estimates (i.e., genetic association with outcome divided by genetic association with exposure) using inverse variance weighting with fixed effects for three SNPs or fewer and random effects for four SNPs or above109. Moreover, weighted median110, weighted mode, simple mode MR111, and MR Egger regression112 were performed to quantify the uncertainty of LDL-C-CAD associations, allowing for violation of IV assumptions. Then, we performed colocation analyses under the hypothesis prioritization for muti-trait colocalization framework to assess the posterior probability of a shared variant within or near (±10 kbp) of the druggable gene, expression quantitative traits (eQTLs) and CAD using the default settings of prior probabilities. We extracted summary statistics of eQTLs from the eQTLGen Consortium (https://www.eqtlgen.org/phase1.html)61. A posterior probability greater than 0.8 was considered strong evidence of colocalization94. Next, we conducted a phenome-wide MR using 78 clinical endpoints with ICD-10 diagnoses in the UK Biobank (https://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank). Before the analyses, we transformed the genetic estimates derived from the linear mixed model to odds ratio (OR) for binary outcomes, adhering to the formula provided in the MRC IEU UK Biobank GWAS pipeline, version 18/01/2019 (https://data.bris.ac.uk/data/dataset/). Finally, we explicitly emulated hypothetical target trials using the 29-year follow-up data from CMCS to investigate the genetically mimicked LDL-C-lowering effects encoded by APOB, LDLR, and LPA loci on ASCVD, CVD, and all-cause mortality. Table 2 describes the protocol of the target trial and the target trial emulation.

Responses