Achieving at-scale seascape restoration by optimising cross-habitat facilitative processes

Introduction

Unless new ways to scale and accelerate restoration of seascapes (comprised of multiple coastal marine ecosystems) are developed and implemented, it is unlikely that global and international targets for restoration (e.g., UN Decade on Ecological Restoration and EU Nature Restoration Law), and the reinstatement of ecosystem services derived from these habitats, will be met. Restoration, defined as the assisted recovery of habitat types that have been damaged, degraded or destroyed1, has occurred successfully for many decades on single habitats2. Moving from isolated, single-habitat restoration approaches to those that restore multiple habitats simultaneously or sequentially, or that aim to restore connections within the broader seascape (collectively and hereafter ‘seascape restoration’; Box 1), should help scale-up restoration efforts and maximise benefits3. However, most published coastal marine restoration research has focused on restoration of a single habitat type rather than multiple habitat types, simultaneously4 and only 12% of restoration projects are strategically designed with seascape connectivity in mind5.

To optimise seascape restoration, we need to better understand and be cognisant of the facilitative processes that exist between habitats when designing and implementing restoration6. Facilitative processes are positive interactions, such as wave attenuation, sediment stabilisation or nutrient cycling, that occur between habitats and help support the characteristic distributions of habitats across seascapes7. Whilst several facilitative processes that can enhance seascape connectivity, ecological functioning, and resilience are well established (e.g., coral reefs attenuating wave energy, enabling seagrass establishment8; mangroves retaining nutrients and sediment, improving water quality in the surrounding areas for seagrass and coral reefs9), we lack a clear understanding of the spatio-temporal dependencies of facilitative processes across coastal habitats. To achieve seascape restoration at-scale, practitioners, scientists, managers, engineers, policymakers and stakeholders need to move from siloed approaches focusing on a single habitat in isolation, to those that incorporate cross-disciplinary expertise on how processes occur across different spatial scales and habitat types and include governance and permitting arrangements that enable multi-habitat restoration.

An understanding of how facilitative processes operate over time and space is needed so that they can be accounted for and harnessed in restoration practice. The strength of a facilitative process generated in one habitat and its impact on the maintenance or recovery of another habitat will depend on the distance between, size and spatial arrangement of those habitats7,10, and a suite of abiotic drivers11. For example, the extent of mangrove habitat, its distance from adjacent seagrass meadows and the amount of suspended sediments flowing in from the catchment will influence the amount of sediment trapping benefit that the seagrass meadows receive from the mangroves9. Thus, the quantification of facilitative processes is essential to scale restoration planning. However, there is a disconnect between our understanding of the spatial scale at which processes underpinning facilitation occur, and the spatial scales at which restoration occurs. The physical, biogeochemical and biological processes supporting cross-habitat facilitation can occur across distances of at least tens to hundreds of metres10, but most examples of cross-habitat facilitation reported in the literature have been described for spatial scales less than one metre4. Restoration of coastal marine habitats can range from tens of square metres to thousands of hectares, depending on the objectives and type of habitat restored2,12. Describing the optimal lateral distances and spatial arrangements of habitats to target in seascape restoration to help overcome this theory-practice mismatch remains a crucial knowledge gap.

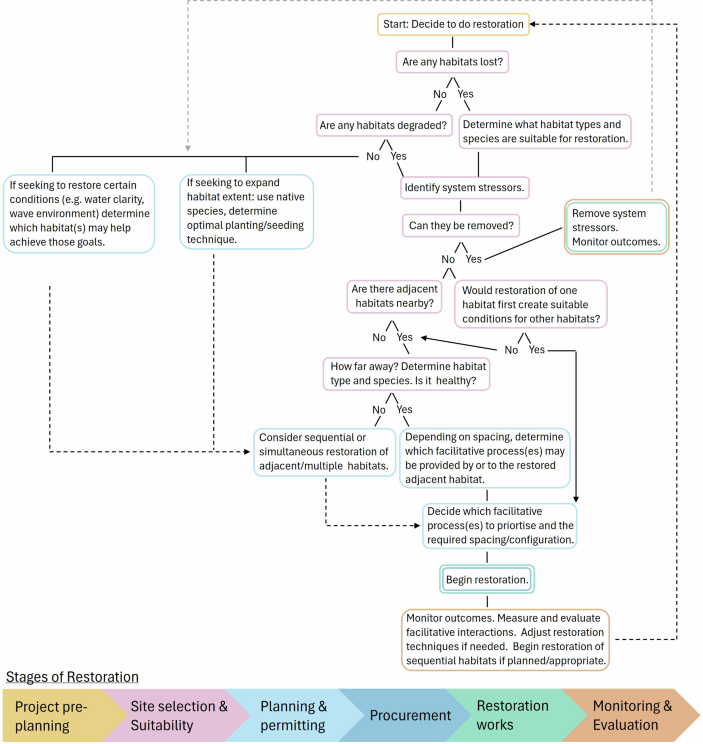

With increasing understanding around the benefits of and funding for multi-habitat seascape restoration13,14 there is an urgent need to identify how knowledge of cross-habitat facilitation can be used to inform site selection and the spatial arrangement of restoration interventions to enhance outcomes5. Describing how physical, biogeochemical or biological processes are involved in cross-habitat facilitation4 can allow for consideration of how the presence and spacing of individual restored habitats may interact with or influence the surrounding seascape3. This information can help inform how ‘sequential multi-habitat restoration’ of one habitat can later enhance restoration success of a second habitat (Box 1). In other instances, this information may be used to overcome, offset or ameliorate compromises in restoration design caused by external constraints such as funding or permits (Box 2). Finally, the ability to identify tradeoffs in design choices, like spacing that optimises the influence of one process over another, may help to better predict and plan for the desired outcomes of restoration projects.

Seascape restoration is a rapidly growing field13, and the ways in which cross-habitat facilitation might be incorporated within multi-habitat restoration approaches will vary depending on local site conditions and the restoration approach. We first provide examples of three multi-habitat restoration typologies that are used in seascape restoration (Box 1). We have included definitions of multi- and single-habitat restoration typologies in which cross-habitat facilitation can be harnessed to achieve seascape restoration. We then outline six processes that underpin seascape cross-habitat facilitation: wave attenuation, sediment dynamics, nutrient processing, water filtration, carbon dynamics and alkalinity export, and animal- and plant-mediated facilitation of other habitats. For each, we define how the process can be quantified and how it is influenced by particular parameters within various habitats. Previous studies have synthesised information on the magnitude by which habitats can regulate facilitative processes9, the types of facilitative interactions occurring between pairs of coastal marine habitats4, and, where possible, the spatial scale over which these interactions have been quantified4. The latter is highly biased towards studies of interactions over small spatial scales (<1 m) because empirical measurements are more feasible at this spatial scale, yet spacing between different habitats in multi-habitat restoration would, in most instances, occur over much larger scales (e.g., tens to thousands of metres). Therefore, there remains a critical knowledge gap about the strength and certainty of the lateral spatial scales over which cross-habitat facilitative processes can occur and how they can be applied to optimise seascape restoration that harnesses facilitation. Here, we seek to address this knowledge gap by providing an overview of the known lateral spatial ranges for each of six facilitative processes. While other types of interactions (e.g., negative ones such as competition, predation or herbivory10,15,16) can be just as important in influencing community structure and adjacent habitats, their impacts on restoration outcomes have received attention in other recent research17,18,19. Finally, using a multidisciplinary and multi-organisational approach—including practitioner, academic, industry contractor and government research perspectives—we illustrate how this information can address knowledge gaps that, when filled, will allow us to better harness facilitation for effective implementation of seascape restoration at scale.

Physical, biogeochemical and biological processes that occur across habitats

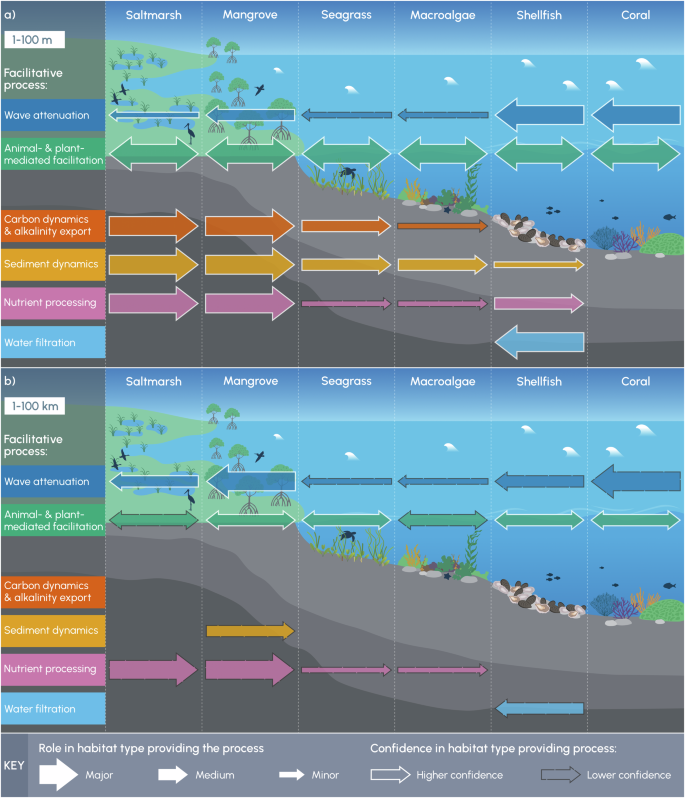

This section seeks to provide information that will help inform how seascape restoration can harness cross-habitat facilitation. We first define terminology relating to six key physical, biogeochemical and ecological processes underpinning cross-habitat facilitation, and then provide examples of how they operate. While we focus on these six process categories, there are many other ways in which habitats may interact to influence each other, including negative interactions. The processes of focus were identified using a cross-disciplinary approach, which included a combination of elicitation of knowledge from experts specialised in different physical, biogeochemical or ecological areas of research, paired with a synthesis of key literature related to facilitative processes that were identified by these experts. Each subsection summarises processes that are associated with six coastal structured habitats that are created by habitat-forming plants and animals: coral reefs, shellfish reefs, macroalgae forests, seagrass beds, saltmarshes and mangrove forests (Fig. 1). Whilst discussed separately, many processes intersect and, where relevant, we identify overlaps among different processes.

We illustrate the role that different habitats play in providing facilitative processes at the scales of a) 1–100 m and b) 1–100 km. Arrow widths represent the relative significance of the role (major, medium or minor) and the outlines represent the level of confidence (solid white outline = higher confidence, dashed grey outline = lower confidence) that a habitat type plays in providing a process at each scale. The absence of an arrow does not mean that the facilitative process does not occur, but rather that research has not yet demonstrated the occurrence of the process for a specific habitat type and spatial scale. The relative significance and levels of confidence for each process were elucidated from expert knowledge and supporting literature.

We then summarise the complex interdisciplinary information on facilitative processes that is needed to guide those conducting research, making decisions and implementing seascape restoration, including known examples of facilitation and the potential spatial scales of operation. Although many facilitative processes may also benefit humans as ecosystem services (e.g., wave attenuation, water filtration, carbon trapping), here we focus on the benefit of these processes to other coastal marine habitats (facilitation). We then illustrate how this information can be used when designing seascape restoration (Box 2).

Wave attenuation

Wave attenuation is the reduction of wave energy through wave shoaling, refraction, diffraction, wave breaking and energy dissipation due to bottom friction and canopy drag20. Coastal habitat-forming species modify the depth and rugosity of the seabed, helping to attenuate wave energy21. The attenuation of wave energy facilitates other species establishment and persistence by broadening the environmental windows of opportunity22. For example, a reef that induces wave breaking and wave attenuation, can enable the persistence of seagrass behind the reef8.

Key parameters that govern wave transformation include wave height, wave direction, and wavelength (the combined effect of wave period and water depth). These parameters undergo non-linear changes during wave transformation that alter the dominant wavelength spatially across the system23. For example, swell waves shoal and break on reef-crests and headlands, generating longer infra-gravity waves that propagate into reef lagoons and along beaches24. The wave height and wavelength control the movement of water at the seabed, which interacts with benthic habitats that provide flow resistance (drag) and drive sediment transport through friction.

The effectiveness of benthic habitats (“canopies”) in attenuating wave energy depends on the geometry and stiffness of the organism’s structure, such as the shape or density of the dominant species of coral, shellfish or mangrove25,26. From a hydrodynamic perspective, the canopy geometry is characterised by the area presented to flow which, combined with the canopy spacing (habitat density, e.g., distance between mangrove roots) and flow velocity, reduces flow within the canopy, and dissipates wave energy due to friction and drag27. For flexible organisms (seagrass, saltmarsh, macroalgae) the geometry changes across the wave cycle as the organisms move with the flow of water. Water depth also alters the magnitude of wave reduction by benthic habitats28. While the details of the wave transformation and attenuation processes are complex, non-linear and multi-scale, the reduction in wave height and changes in dominant wave frequency can be observed visually and measured quantitatively28. However, modelling wave-vegetation interactions is challenging and an area of ongoing research29.

The benefit of wave attenuation by one habitat for another habitat has been documented at scales ranging from metres30 to kilometres8,31 (Fig. 1). When considering the physical parameters such as length of habitat structure or distance and area of influence, wave attenuation by one habitat may benefit other habitats over scales of tens to hundreds of kilometres away32. For example, the Great Barrier Reef provides wave attenuation to inshore habitats across these distances. The ability of benthic habitats to attenuate waves may be especially important in the future as storm events are expected to increase in intensity, since storm waves and surge place greater stress on the survival of coastal marine habitats. Coastal habitats can attenuate storm surge height33 and may also trap and filter increased sediment or nutrients following storm conditions (see Sediment dynamics; Nutrient processing).

Sediment dynamics

Benthic sediment dynamics, including stabilisation, accretion and destabilisation, influences and are influenced by the presence and structure of coastal marine habitats. Sediment stabilisation is the trapping of particulate organic matter from the water column. This process contributes to sediment accretion, which is the accumulation and deposition of sediment particles. Sediment stabilisation also reduces the direct smothering of propagules and minimises shading caused by sediment plumes, which can detrimentally impact adult and juvenile habitat types34,35. The process of sediment accretion also provides more available substrate for settlement and growth of habitats. However, excessive sedimentation can pose a risk by burying seedlings or propagules, inhibiting their growth by restricting access to light and oxygen, which can result in high mortality rates. The effects of sediment burial on seedlings are influenced by the rate and frequency of sediment deposition, as well as the resilience of the particular species36.

The key parameters that govern sediment transport are current velocity, sediment settling velocity, and suspended sediment concentration37. Sediment deposition and transport are driven by current velocities to reach a balance between settling and resuspension. The particle settling velocity is determined by particle shape, size and density, which are continuously changing by aggregation and disaggregation38. Additionally, the bottom roughness created by marine habitats can alter friction at the seabed, ultimately affecting sediment resuspension39 (see Wave attenuation).

The presence, structure and orientation of coastal marine habitat-forming species can influence sediment dynamics by reducing near-bed turbulence, promoting sediment deposition, and inhibiting the resuspension of settled mud40,41. These processes reduce turbidity, thereby increasing benthic light availability and facilitating the growth of photosynthesising species like seagrass, macroalgae and coral zooxanthellae42,43. The spatial scale of positive impact can be hundreds of metres to a kilometre away44 (Fig. 1). Species-specific morphologies can affect current velocities, thereby influencing erosion and deposition of sediment and sedimentation rates. For example, there is a positive correlation between both the height of marine macrophytes and the reduction in current velocity, and the surface area of marine macrophytes and the abundance of trapped sediment particles45. Sediment trapping from the water column reduces sediment resuspension rates and, over time, can alter the critical photic depth that determines the occurrence of marine habitats46. Further, these habitats can also significantly impact the sediment budget of seascapes and influence the coastal processes and sediment transport in a system. Recent models (e.g., COAWST47) have investigated the flow-vegetation interaction between habitats with flexible structures and processes regulating sediment dynamics, but further work is needed for rigid habitats. Interactions among habitats, sediment properties, and hydrodynamic conditions can also regulate erosion, which may be more extreme after short-term episodic events like storms, which can lead to both sediment erosion and habitat loss48.

Nutrient processing

Nutrients are essential for the growth of plants and animals, but need to be supplied in the right forms, quantities and timing. Changes in nutrient supply can have deleterious impacts on growth at the physiological level49, and at the ecological level, will confer advantages to some taxa over others50. Therefore, nutrient processing via habitat-forming species can help balance the appropriate nutrient provisioning to other habitats.

Many coastal ecosystems have the capacity to reduce nitrate (NO3−) concentrations and ameliorate the negative effects of excess nutrients on adjacent ecosystems. Mangroves, saltmarshes and seagrasses all have mildly anoxic soils that are rich in carbon (see Carbon dynamics and alkalinity export). They are located near the coast where nutrient pollution enters via rivers, groundwater, or surface runoff. These characteristics are ideal for denitrification, which is the conversion of NO3− to N2, and the permanent removal of nitrogen (N) from the water column. Additional processes for N removal are plant growth or the accumulation of N as woody biomass, soil accumulation of particulate N, and anammox or the conversion of ammonium (NH4+) to nitrogen gas N251.

These processes result in changes in concentrations of N and transformations among N species that could have benefits for different ecosystems within a seascape. For instance, some coastal wetlands (mangroves, saltmarsh) can transform NO3− to NH4+ through dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA), which can result in the export of NH4+ to waterways52. This process may facilitate N uptake by phytoplankton, which prefer NH4+ over NO3−, resulting in high productivity that nearby shellfish reefs can consume and convert to particulate N53,54. Furthermore, the accumulation of particulate N in the soil could be remineralised back to NO3− and denitrified in nearby seagrasses providing a final polishing of the water column before reaching coral reefs, providing the low nutrient conditions in which they thrive. These processes have typically been documented over spatial scales of a couple metres55 but may occur over tens or hundreds of metres, depending on the habitat area and catchment size51 (Fig. 1). Importantly, nutrients are consumed by a variety of taxa including bacteria, primary producers, phytoplankton and zooplankton56 and as such, competition for nutrients could potentially impact cross-habitat interactions. However, competition for nutrients such as N is most likely to occur in settings where N is limited57; therefore, understanding of location-specific parameters is needed when planning to harness cross-habitat facilitation in restoration.

The presence of benthic marine habitats can modify phosphorous and sulphide levels. Coastal wetlands can retain phosphorous within sediments58 (see Sediment dynamics), or in dissolved forms (e.g., soluble reactive phosphorous52), potentially reducing incidences of eutrophication and thereby benefitting neighbouring habitats. At the sub-metre scale, sulphide reduction by benthic bivalves benefits adjacent seagrass habitats59,60 (see Animal- and plant-mediated facilitation). The processes of nutrient reduction through the passive filtering of wetlands may be especially important under storm conditions, when storm surge and tidal inundation deliver higher-than-average volumes of particulate- and nutrient-rich water into wetlands61.

Water filtration

Water filtration is the process of removing suspended particles from the water column and may occur either actively or passively. Water column particulate matter may be comprised of different trophic levels of plankton, or organic and inorganic particles (see Sediment dynamics; Carbon dynamics and alkalinity export). In this section, we focus on active filtration (for passive filtration, see Nutrient processing), which in coastal ecosystems occurs by suspension feeders, such as bivalves that filter large volumes of water, ingest the edible particles, and deposit rejected particles as biodeposits on the sediment surface62. Furthermore, water filtration can aid in the removal of pollutants, contaminants, and pathogens associated with suspended sediments63,64. Together, these processes benefit water clarity and purity.

The water filtration capacity of a species is often assessed through an individual’s filtration rate in laboratory studies where physiological factors such as size and environmental factors such as temperature, salinity, flow rate, seston concentration and particle size have been demonstrated to influence rates65. Over reef to estuary spatial scales, filtration rates are determined by hydrodynamic factors including current speed and water residence time, and population dynamics like density or reef size66. For shellfish, population filtration capacity and water residence time influence the rate at which particles are cleared from the water column. Restoration of shellfish reefs are expected to result in improvements to estuary water quality. For example, historical losses of oyster reefs in Chesapeake Bay resulted in declines in water quality62 but restored shellfish reefs can provide water-quality improvements67.

Water filtration has important down-stream effects in estuarine systems and depends on local- and estuary-scale hydrodynamics, and the spatial position and distribution of the filtration provider (Fig. 1). In particular, the cross-habitat facilitative benefit of water filtration by shellfish improving water clarity is well-established for adjacent seagrass habitats68. Seagrass habitats are sensitive to turbidity, which reduces seafloor light availability, thereby impacting seagrass productivity69. The benefit of water filtration on seagrass may occur on scales as small as centimetres or up to a few kilometres, depending on the size of the estuary or embayment70 (Fig. 1). Directionality is an important factor for cross-habitat facilitation from water filtration, with benefits generally found “down-stream”. But tidal and riverine outflow processes are complex, so that “down-stream” locations may vary temporally over tidal-seasonal scales.

Carbon dynamics and alkalinity export

The marine carbon (C) cycle plays a major role in global C cycling and the growing interest in marine Carbon Dioxide Removal (mCDR) approaches to sequester excess atmospheric carbon71. The mCDR concept most related to seascape restoration is “blue carbon”: the management of C stored and carbon dioxide (CO2) removal by CO2 fixation by vegetated marine habitats72. However, there is continued research on the role non-vegetated habitats may play in this process73. Many aspects of the C cycle are needed for mCDR and blue carbon accounting but not all are important for cross-habitat facilitation. For clarity, we first define key components of the C cycle and then describe how some are important in cross-habitat facilitation.

Carbon sequestration by macrophytes is the uptake and storage of C via sediment trapping or accumulation of biomass, mostly as wood and roots74. Biomass is continually transferred to sediments where physical and chemical changes in the sediment (diagenetic processing) convert part of the photosynthetically derived C to microbial C, dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) or methane75. This diagenetic processing influences the portion of deposited C that is sequestered in sediments as long-term C, emitted as gas or exported to surrounding waters76. While sediment trapping sequesters C and also provides clearer water (see Sediment dynamics), the links between biomass accumulation and facilitative cross-habitat interactions are less clear77. For example, dissolved organic C and litter export to reefs or coastal waters accounts for a large proportion of the C cycle78; these organic C exports are likely important77, but are highly variable in terms of the benefits to other habitat types. Further studies are needed that ascertain habitat-specific responses to C exports.

Inorganic C also plays an important role in cross-habitat facilitation. DIC is composed of four carbon species (CO2aq, H2CO3, HCO3− and CO3−2). Production of CO2aq (herein, aqueous CO2aq and carbonic acid H2CO379) from metabolic or chemical processes of habitats decreases the pH and acidifies waters, affecting adjacent habitats. Waters that are supersaturated in the partial pressure of CO2aq relative to the atmosphere will off-gas CO2, increasing pH until equilibrium is reached. Thus, the effect of acidification is greatest closest to the CO2aq source, decreasing over space and time. The production and export of alkalinity (including HCO3− and CO3−2) increases the ability of water to buffer (reduce) acidity80. The ability of marine habitats to generate alkalinity occurs through at least two processes: photosynthesis81 and organic matter decomposition82, both of which can result in increased pH. Alkalinity export is likely to be highest in estuaries with large tidal amplitudes83 and after rainfall84.

Climate change is causing acidification of the oceans79. Alkalinity export from tidal wetlands and intertidal and submerged aquatic vegetation81,85 to neighbouring calcified habitats (shellfish and coral reefs) within zero to tens of metres, could support their restoration86,87, especially in poorly buffered environments or those highly susceptible to acidification (Fig. 1). Although questions remain around the relative magnitude of C fluxes provided by certain habitats and how to attribute the amount of alkalinity export to a certain area of vegetation88, we are beginning to better understand the spatial variability and scales involved. For example, C storage by vegetated habitats may vary depending on the presence of other vegetated89 or non-vegetated90 habitats and across different regions91,92.

Animal- and plant-mediated facilitation of other habitats

Here, we describe processes attributed to the movement and/or establishment of coastal marine animals and plants that can facilitate the establishment or persistence of habitat-forming species. Many of these processes are underpinned by one of the five processes described above. However, in the context of this section, these processes are either directly provided by animal or plant movements (e.g., nutrient transport by fish, abrasion by macroalgae fronds), or result from direct plant or animal mediation of the environmental and biological conditions at the site (e.g., shading, competition reduction, herbivory). We acknowledge that in addition to the positive, facilitative interactions discussed below, there are a suite of important negative interactions that exist among plant and animal species in coastal habitats. Indeed, managing for negative species interactions has long been a foundational principle in restoration and conservation science93. For instance, invasive species control has and continues to be key for restoration success19. A key research gap is to characterise the ecological contexts or spacings in which interactions switch from positive to non-existent or negative.

Cross-habitat facilitation is mediated by mobile animals transporting energy and nutrients among habitats94 and through animals migrating across habitats and supporting key ecological functions that support ecosystem resilience in one or more of those habitats95. In this sense, increased functional connectivity of animals between different coastal marine habitats can significantly enhance restoration outcomes if they have a positive effect on the likelihood of settlement, growth, or persistence of habitat-forming species. Across seascapes, classic examples of these processes include mangroves providing nurseries for herbivorous fish that clear algae and facilitate coral recruitment and growth (hundreds of metres to kilometres scales96), bioturbators oxygenating sediments and processing pollutants to create suitable conditions for other species (centimetres to metre scales97), and animal-mediated nutrient transport between different habitats via excretion (metres to hundreds of metre scales94) (Fig. 1). However, the presence of these animals may not equate to the presence of a particular facilitative process (e.g., herbivory of a competitive algae from coral reefs98) and necessitates context-specific consideration of whether a process(es) will occur.

Facilitation may also be mediated by sessile habitat-forming animals and plants. The mechanisms by which these organisms directly facilitate others includes competition reduction (e.g., abrasion that reduces competitor settlement within 1 m99), or modification of environmental conditions within a few metres (e.g., shade100 or temperature101) that allow for the establishment of another habitat (Fig. 1). However, these same processes that may be beneficial for a particular life stage and habitat type (e.g., abrasion by kelp that enables juvenile oyster settlement99), could presumably be detrimental to other habitat life stages or types. Another important mechanism is through the process of colonisation and succession. For example, colonisation by saltmarsh vegetation can facilitate the subsequent establishment of mangroves (Box 1) by trapping propagules and altering hydrodynamics or temperature at the site102. Alternatively, mangroves are capable of encroaching into saltmarsh (particularly as temperature increases at their poleward edge), at times leading to coastal squeeze and saltmarsh losses103,104, reinforcing the need to consider both positive and negative interactions during restoration planning.

As the scale and scope of seascape restoration programmes expands, and especially when restoring multiple habitats simultaneously, the importance of these considerations likely increases. Firstly, enhancing connectivity between restoration sites and remnant habitats maximises the likelihood that species that drive facilitation will recruit to restored habitats. Secondly, maximising connectivity between new restoration sites of different habitat types helps ensure these connections can result in synergistic benefits across both new habitat types. Ultimately, the ability of animals or plants to mediate facilitation through multi-habitat connectivity depends on the species present, the ecological function by which they facilitate another habitat (e.g., grazing for competition reduction, nutrient or propagule transport, modification of environmental conditions), and the distance over which this process can effectively occur. Given the simultaneous increase in the likelihood of positive and negative interactions existing from enhancing connectivity, restoration practitioners would benefit from a sound ecological understanding of their system to account for all plausible outcomes (see ref. 19).

Minima and maxima lateral distances of cross-habitat facilitative processes

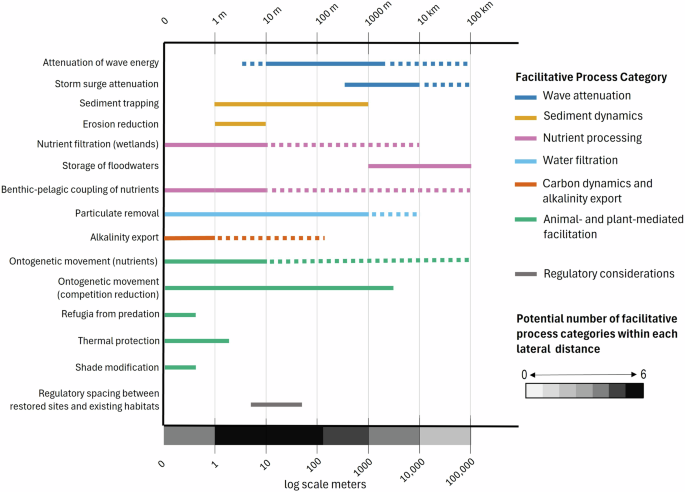

Through expert opinion of the authorship team, we characterised the likely minimum and maximum lateral distances across which each facilitative process may occur in the context of seascape restoration. The lateral minima and maxima of these processes illustrate opportunities for spacing restoration projects to harness particular processes (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S1). For example, structure-based facilitation provided by habitat-forming species (e.g., shading, abrasion) generally occurs within distances of 0–1 m in predominately nested or co-occurring habitat patch mosaics, but larger physical processes (e.g., wave attenuation) occur from distances of tens to hundreds of metres. Through this process we identified examples of all six processes underpinning cross-habitat facilitation overlapping at distances between 1 and 100 m. At all distances considered, at least three processes overlapped (Fig. 2). Uncertainty tended to increase with increasing distance, suggesting that the practicality of harnessing facilitative processes in restoration may decrease at these larger spatial scales.

The x-axis represents the log-scale lateral distance of a process in metres. Solid lines represent known distances of facilitative processes; dashed lines represent uncertainty in the distance. The horizontal grey line from 5 to 50 m represents the common buffer that restoration sites are usually required to be placed away from other existing habitats to potentially mitigate negative effects. References in Supplementary Table S1.

Importantly, for biologically mediated interactions, there is likely a distance-dependent shift between positive or negative interactions. Depending on context, biologically mediated interactions may be negative at close distances (<10 m; overgrazing of algae and corals by parrotfish105), but positive at longer distances (>1 km; grazing of algae by parrotfish that helps corals96). Therefore, whether the ecological processes described herein are facilitative at certain distances will be largely context-dependent, based on ecological conditions and the species present and their traits106. The effects of seascape configuration on biologically mediated facilitation may depend on the ecological function resulting in facilitation. For example, in Australia, isolated coral reefs tended to have greater rates of herbivory than reefs located closer to other reefs, which tended to have higher rates of piscivory; additionally, proximity to mangrove or seagrass habitats did not have a strong influence on herbivory or piscivory in this system107. There may be similar shifts between positive and negative effects of physical and biogeochemical processes at certain distances, but these did not arise during our assessment.

Interestingly, current restoration permitting practices often seek to mitigate potential negative interactions among habitats by requiring a buffer between restoration sites and existing habitats. Exact permitting requirements vary by country and jurisdiction, and local classifications of restoration actions (e.g., development or restorative), but restoration actions are generally limited 5–50 m within or adjacent to areas designated as other types of habitat. Two states in Australia (New South Wales and Queensland) require a buffer of 10–50 m around seagrass beds and at least 100 metres around “sensitive” habitats108,109. In the United States, the Florida Coastal Zone Management Act requires a 30 m buffer zone around seagrass beds in areas of coastal development110. However, these buffer distances are not necessarily based on an ecological understanding of all the potential interactions that can occur111, but rather an attempt to mitigate harm. For example, long-distance negative interactions are also common and can regulate ecosystems10, and the distance over which they operate may even exceed these permitting buffers. Therefore, it is necessary to understand how both positive and negative interactions operate in seascapes to move forward with scaled seascape restoration. Without this knowledge, implementing a somewhat arbitrary buffer distance may preclude the opportunity for some facilitative interactions to occur and unintentionally limit restoration outcomes.

By considering the gaps or overlaps in lateral distances of multiple processes, we can identify where there may be trade-offs in designing restoration with spacing that seeks to optimise certain processes related to project objectives. For example, a restoration project seeking to maximise both wave attenuation through the restoration of a reef system and sediment dynamics via sediment trapping through the restoration of mangroves may prioritise a spacing of 10–1000 m between these two habitats. However, at this distance range, the ability for wetlands to passively filter nutrients or aid in alkalinity export is less certain than the ability of the reef to attenuate waves, necessitating a decision in which process(es) to prioritise. Although not the focus of this manuscript, negative biotic interactions (e.g., competition, herbivory, predation) are highly context-dependent and depending on local conditions, the spacing that influences these interactions is something that needs to be considered when designing restoration.

Incorporating cross-habitat facilitation in seascape restoration

Seascape restoration is being operationalised through multiple restoration modes (Box 1) and this review demonstrates that there are opportunities to harness cross-habitat facilitation at multiple spatial scales. Identifying new opportunities for seascape restoration that harnesses facilitation is constrained by numerous biophysical (e.g., habitat suitability for desired restoration species), logistical (e.g., contracts and site access), and social considerations (e.g., stakeholder perceptions of and support for proposed restoration projects). Therefore, practitioners working within these constraints need tools such as decision support frameworks, and conceptual and restoration suitability models that can help guide the design and implementation of seascape restoration to achieve desired objectives, notably, those related to harnessing cross-habitat facilitation (Box 2). By expanding on best-practices already implemented by practitioners when designing restoration projects, such as identifying clear targets, suitable species and local environmental conditions, the information provided in this review aims to illustrate how seascape restoration can be taken a step further to account for and harness facilitative interactions.

The spatial configuration of the seascape and habitat types therein, is a key determinant of the strength of facilitative interactions. The patch size and configuration of habitat types (including distance between patches of the nearest neighbour as well as distance from other habitat patches in the overall seascape mosaic), varies with environmental context and in turn can influence the functioning or provisioning of facilitative processes by these habitats112,113. Additionally, the magnitude of facilitation may be determined by the spatial configuration of the habitat within the broader context of the seascape. For example, we would expect mangrove facilitation of coral reefs by trapping sediment runoff to be of greater importance when mangroves are located at the mouths of rivers than when mangroves are located on an open coast114. The final spatial configuration of restoration projects will ultimately be influenced by a variety of environmental and social factors115 (Box 2). Therefore, seascape restoration planning must also consider how the eventual configuration will influence the strength of prioritised or desired facilitative interactions.

Although not a focus of this paper, the same physical, biogeochemical and biological processes of cross-habitat facilitation also underpin self-facilitation within a single habitat type60, which in turn can influence facilitation of other habitats. Having many medium-sized seagrass beds rather than one large seagrass bed facilitates more diverse fish nurseries and overall habitat values, while also reducing erosion in the adjacent seascape116, which in turn can lead to a greater diversity of fish at adjacent habitats. Processes affecting habitat patch dynamics can include ontogenetic movements, hydrodynamic conditions, and the presence of grazers that influence coral settlement117,118; these same processes were identified as occuring between corals and other adjacent habitat types at larger scales (Fig. 2). Therefore, it is important to understand that restoration seeking to harness cross-habitat facilitative processes will also depend on the same processes operating within a single habitat type.

Restoration remains a costly endeavour12, requiring careful consideration of the potential successes and failures of restoration actions. Negative interactions such as competition and predation or herbivory can have negative outcomes on restoration19. For example, although saltmarshes can facilitate mangroves by trapping their seeds and modifying abiotic stressors (e.g., substrate provisioning and temperature and shading, respectively102), competition for space between these plants at later life stages can inhibit the growth and expansion of one or both of these habitats119. Further, whether these cross-habitat interactions are positive or negative may be influenced by looming global threats such as climate change. Increasing temperatures as a result of climate change and the subsequent poleward expansion of mangrove habitat has led to the intrusion of mangroves into saltmarsh habitat at these geographic locations104. Therefore, it is critical for managers and practitioners seeking to conduct seascape restoration to have a clear understanding of how their restoration sites may be influenced by both facilitative and negative cross-habitat processes, and how these processes may be altered further under a changing climate.

Restoration actions must be paired with climate change mitigation and conservation measures that seek to first protect and halt the decline of natural habitats120. Following this, climate-smart coastal marine restoration should include clear strategies to adapt to pressures faced by climate change121. To do this, practitioners, managers and scientists must work together to implement restoration monitoring programmes that will ultimately inform required adaptation plans of these systems122.

Future research priorities in cross-habitat facilitation in seascapes

We have demonstrated how facilitative processes vary across lateral distances to help inform seascape restoration design. We show that different processes occur in different habitat types, suggesting that habitat heterogeneity may increase overall opportunities for cross-habtiat facilitation within a seascape. Crucially, we also demonstrate how adaptive management of restoration can minimise unintended consequences of certain actions seeking to harness facilitation (Box 2). Still, there remain two key research priorities related to harnessing cross-habitat facilitation in seascapes. The first priority is to better understand the temporal (including seasonal) dependencies of cross-habitat facilitation through restoration. For example, the magnitude by which a coral reef attenuates waves depends on its structural complexity21; therefore, wave attenuation by a newly restored coral reef will take time to reach the desired complexity for this process to occur. Seasonal variations in the density or structure of a habitat-forming species may also affect these processes (e.g., seagrass density and variability in wave attenuation123). The second priority is to better understand the non-linearity of these processes. The magnitude of facilitation along a lateral distance over which we know it operates (Fig. 2) may be non-linear. Therefore, we need to understand the non-linearities of these processes and how they interact with each other across different spatial scales to better incorporate and plan for cross-habitat facilitation in restoration. This may need assessment on a context-specific basis, where a strong understanding of local environmental conditions (bathymetry, habitats present, and stressors) can be incorpoated into a model that disentangles these non-linearities of cross-habitat facilitation. Although this review has predominately provided examples of processes occuring across pairs of habitat types in seascapes, it is important to consider that facilitative processes may have flow-on effects (facilitation cascades11) and/or interact with each other within the seascape.

Conclusion

We face an urgent need to repair nature globally as articulated by the UN Decade on Ecological Restoration and Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. To mitigate the combined climate and biodiversity crises, it is imperative that we scale-up restoration quickly and effectively. Facilitation is intrinsic in coastal marine environments6,10. To achieve at-scale seascape restoration, cross-habitat facilitative processes need to be better understood and harnessed in restoration. While these processes are context-dependent and occur across a large range of lateral distances, we highlight where opportunities exist to achieve at-scale seascape restoration using cross-habitat facilitation and raise key questions that demand future research .

Responses