Addressing contemporary threats in anonymised healthcare data using privacy engineering

Introduction

Data can be either useful or perfectly anonymous, but never both— Paul Ohm1

Data privacy is a growing concern in healthcare. Medical cyber-attacks are increasingly frequent2 and there is ample evidence that trusted healthcare organizations have transferred personal identifiable information (PII) to industry3,4,5,6. Nevertheless, such leakage of personal data likely underestimates the scale of contemporary threats to data privacy and identity.

Technological advances now make it possible to identify important characteristics of an individual without the need for PII, even in datasets that are compliant with privacy regulations. Linkage attacks enable inference of an individual’s precise identity (identity disclosure) or specific features (attribute disclosure) without PII, by cross-referencing online repositories in a probabilistic fashion. Linkage attacks have been used to identify individual medical records7 and socio-demographic details1, yet remain in the use agreements of several consumer companies8,9,10. Membership inference attacks (MIA)11,12 infer whether an individual belongs to a specific disease-related or vulnerable social group without PII, that could influence the delivery of services to them and perpetuate disparities of care13. In addition, artificial Intelligence (AI) based novel biometrics can now infer identity from traditionally de-identified sources lacking PII, utilizing data such as ECGs or even patterns of gait14. (Fig. 1) These advances in data availability, computational methods and analytical efficiency have eroded practical safeguards to privacy attacks, and have also introduced new privacy risks.

a Who is involved? Contemporary privacy threats come from intended and unintended users. b What are the Risks? To learn an individual’s characteristics or identity. This can occur by Inferring characteristics from anonymised data including membership of a specific group (membership inference attacks, MIA), inferring a sensitive attribute or inferring identity. These extend risks of direct data leakage of PII. c What are the solutions? Such threats could be addressed by Health Data Privacy Frameworks, that guide the selection of privacy engineering and include components such as the precise task, the type of user, the type of data required, the duration of time for which data are needed, and ethical considerations.

It is important that patients, health professionals, and researchers alike are familiar with these privacy threats, in order to make informed choices15. However, such familiarity may be uncommon16. We set out to review the contemporary health data privacy landscape, which refers to the protection and secure handling of personal health information, for clinicians, researchers, and patients. We then turn to privacy engineering17, a field that provides technical solutions in commerce, and discuss the strengths and limitations of privacy enhancing technologies (PETs) for various health tasks. We focus on a broad framework that could guide selection of appropriate PETs to strengthen privacy while maintaining health data utility between patients, caregivers, administrators, researchers, and industry.

Contemporary threats to privacy

From 2005 to 2019, there were an estimated 3,900 breaches of health data records affecting over 249 million patients18,19. Health data breaches pose unique risks. Unlike user-selected data such as account names or passwords that can be reset or deleted, biomedical identifiers may be difficult – or impossible – to change. There is also a unique tension between data privacy and sharing in healthcare. Principles of patient consent and data protection, encoded at least since the Belmont Report, empower individuals to freely disclose sensitive information and engage with health providers20. Weakening these protections may erode trust in healthcare. Conversely, there are widely held expectations that health data should be shared outside the private patient-carer relationship, to improve societal health and develop future therapies15,21.

Threats to health data privacy

Mitigating data privacy risk historically focused on restricting access to identifiers by specific groups defined by healthcare providers, professional societies, or governments. Identifiers include personal identifiable information (PII), which is any data that can identify a specific individual, or personal data defined by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)22 in the European Union. Personal Health Information (PHI) is a subset of 18 elements defined in the U.S. by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)23. As the healthcare landscape has evolved, so too have the types of entities vulnerable to privacy attacks. For instance, direct-to-consumer services often handle sensitive data, yet may not be covered by privacy legislation. A cyber-attack at 23andMe in 2023 exposed sensitive ancestry information revealing ethnic group membership such as individuals with Ashkenazi Jewish heritage24.

Importantly, de-identifying data may not provide robust protections1. Technical attacks can now attach identities to data that are compliant with widely-used standards for de-identification, to infer attributes beyond what individuals explicitly disclose (Fig. 2). At the heart of these threats is the concept from information theory of the positivity of mutual information25, which informally ensures that the certainty in an unknown quantity (such as an individual’s identity) never decreases as additional information is utilized. A corollary is that reducing the extent of disclosed information may reduce the risk of disclosure.

a Identity Disclosure. Linkage Attacks combine multiple online datasets to infer identity. Aggregated datasets include publicly reported statistical data. Artificial Intelligence can be trained to infer identity from historically ‘non-identifiable’ data such as raw ECGs, chest X-rays or other data. b Attribute and Membership Disclosure. Attribute disclosure can reveal if a patient record has a feature such as alcohol use or a disease, without revealing their precise identity. Membership Inference Attack (MIA) can identify if an individual is present in a dataset, which could be a list of patients who are HIV positive or have not paid their bills. Differencing attacks operate on sequentially released data, to infer the presence of an individual if they are present in one version yet missing in another.

The ways in which characteristics of an individual are inferred depend, in part, on the format in which information is available26. One can broadly consider three formats: de-identified datasets, aggregated information from multiple individuals such as clinical trial data, and AI models.

Threats to de-identified datasets

A key observation is that seemingly innocuous data without PII can be used for ‘re-identification’. One of the earliest attacks is attributed to Sweeney in 2002, who used voter registration combined with other public data to re-identify medical records of the Governor of Massachusetts27. As recently as 2018, patients have been re-identified using de-identified HIPAA-compliant datasets and data aggregated from public newspaper articles28. Such risks are amplified in patients with rare conditions, such as cross-referencing genetic variant data in a public database with social media or news articles. While health data repositories may state that attempts to re-identify patients violate their terms of service, it is unclear whether current safeguards are sufficient to protect privacy.

Artificial Intelligence has added to such identity revelation threats. Using supervised learning paradigms29, AI can associate seemingly non-identifiable biological or behavioural data inputs with public identifiers. Trained AI systems have been used to infer identity from anonymised chest X-ray images30, ECGs31, cerebral MRI images32, or gait33. AI has also introduced new types of threats described below.

Threats to aggregated datasets

Aggregated data were traditionally viewed as free of privacy threats, and publishing statistical analyses of population data is often required by law in the U.S. and other countries7,34. It is now clear that aggregated data may indeed introduce privacy risks. Membership inference attacks35, or more broadly tracing attacks12, can discern whether an individual of known characteristics is present in aggregated data. If the dataset contains sensitive information—such as status of HIV, ethnicity or a vulnerable group—this attack could facilitate discriminatory practices20,36 and further widen disparities in care13,20.

For example, in 2008, Homer et al.11 inferred which individuals were present in a Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS) of published aggregated allele counts. Since members of each GWAS subgroup had a specific disease, this analysis revealed which individuals had the disease37. Paradoxically, MIA can also be applied to synthetic data38, despite their goal of reducing the need for actual patient data, which should be considered when designing digital twins for healthcare39.

Data is increasingly aggregated piecemeal through data portals, in interactive query systems. Differences between the results of two or more queries can reveal information about an individual, which is termed a differencing attack40. The interactive nature of data portals opens the opportunity for a user to adaptively and strategically ask queries that statistically facilitate this threat. A stylized differencing attack is presented in Fig. 2B. The explosive growth of large language models and AI-powered chatbots, which are essentially ‘evolved’ interactive data portals that learn continuously on massive repositories of data41, raises the need to implement strategies pre-emptively to mitigate privacy threats from such models.

Threats to artificial intelligence models

While AI models are used as ‘prediction engines,’ from an adversarial perspective AI models may be viewed as ‘carriers of training data’. After all, the predictive behaviour of an AI model is determined by its parameters, and modern neural networks or large language models (LLM) learn their parameters from training data. These parameters encode statistical summaries of the training data, just as the intercept in a simple linear regression model represents the average, and other parameters represent a unit change in the conditional average. AI models thus present opportunities for adversaries to learn attributes of individuals in the training data.

AI models are also susceptible to MIA, similar to aggregate statistics, based on the principle that models tend to be more ‘confident’ on predictions whose inputs are more similar to their training data42. An adversary could thus query the model, record inputs for which the model has higher confidence, and infer which subjects are likely in the training data. This vulnerability is highest for models that are overfitted, or highly influenced by their training data43. MIA of AI models is not simply a theoretical possibility—but has been applied with astonishing success. MIA has been reported for AI models in neuroimaging44 and large language models45. Chen et al. found that, without additional safeguards, an adversary could infer the membership of an individual in a genomic dataset in convolutional Neural Networks trained on genetic data46. Chang et al. further demonstrated that ChatGPT/GPT-4 is vulnerable to MIA via ‘digital archaeology’, a technique that uncovers digital traces of previous literature, early websites, social media or other content, to infer whether LLMs used copyrighted works in training47.

AI models are susceptible to other forms of privacy attacks. Training data extraction attacks describe the ability of an adversary to recover individual examples from training data and have been successfully levied against LLMs48,49. Model inversion attacks, on the other hand, aim to reconstruct a model’s parameters based on queries50,51, which can then be reverse-engineered to infer sensitive information about its training data. A recent model inversion attack on a personalized warfarin dosing model enabled the prediction of the patient’s genetic markers52.

Historically, privacy protection was often ‘structural’53—in that the time to compute linkages or to perform a differencing attack or MIA provided practical barriers to attacks. Advances in data availability via wearables and other sensing technologies, and increases in analytical techniques and computational efficiency, have eroded these safeguards. AI models are thus not only directly vulnerable to attacks but can be used to facilitate them.

Ethical considerations and legislative strategies

Perspectives on data privacy and data sharing vary considerably54,55,56,57. Traditional guidelines, such as the Belmont principles of respect for persons, beneficence and justice58, may not translate directly to contemporary data sharing such as self-disclosure in social media, nor address privacy threats that infer sensitive information without disclosing PII or PHI.

One solution is to treat all data, even without PHI or PII, as sensitive. This would have dramatic implications on medical practice and research and raises a broader debate on the ethics of withholding seemingly low-risk data that could improve or save lives. Extreme restrictions in data access would also exacerbate bottlenecks in patient care and have been blamed for the slow response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada59. Industry has also voiced concerns that restricting data access may impede technical innovation60, which re-emphasizes the need for discussions on how best to balance health data utility with privacy.

Several ethical frameworks can be applied to health data privacy54,55,56,57. Contextual integrity was developed to define privacy boundaries and data-sharing practices for online services and is based on ethical norms expected by individuals and society57. In general, society expects that sensitive healthcare data will not be publicly exposed61. A major concern of patients is the secondary use of data beyond their original consent, particularly by industry62, yet industry has a central role in innovation.

Several legislative protections for health data privacy are described15. Historically, the focus has been anonymisation of data, with the primary privacy law in the U.S. being the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)23. HIPAA does not regulate data per se but defines groups (‘covered entities’) for whom access is regulated. Such legislation may provide suboptimal protections as healthcare has evolved, and direct-to-consumer services or the providers of wearable devices are typically ‘non-covered entities’ (unregulated by HIPAA)23.

In the European Union (EU), the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 2016/679 or its United Kingdom counterpart (UK GDPR) define protections for health and personal data more broadly—regardless of custodian, format or collection method22. The legislation also gives consumers greater control over the consent and use of biometric and genetic data, that are discussed specifically in a ‘special category’63.

Supplemental protection may also be provided in the U.S. by organisations such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which has overseen actions against direct-to-consumer services engaging in ‘deceptive or unfair’ practices in relation to consent or data sharing64, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) or the Genetic Information Privacy Act (GIPA)22.

Thus, the translation of any technology for health data privacy into robust practical solutions raises ethical, legal and technical challenges. Safeguards should protect sensitive data throughout the lifetime of an individual, or even their offspring, which is challenging as healthcare organisations or consumer companies grow or consolidate65. A central component in implementation must be shared decision-making with the patient or data owner (‘No decision about me without me’). The dialogue should be transparent, considering current and future data uses, for what types of data, and which specific protections are—or are not—available. This in turn will require education of patients and caregivers on the risks and benefits of more and less restrictive options, which is currently suboptimal16.

Privacy framework for health data

The central health data need is to facilitate access by authorised individuals while preventing unwanted disclosure of identity, sensitive attributes or group membership of an individual or cohort. In primary data use, the patient (data owner) gives explicit consent to use their data for care, which is regulated by restricting authorisation. Nevertheless, this ‘release and forget’ model often provides unnecessary data access. For instance, it is not clear why clinicians at an Institution can access data for patients they are not caring for, or for long after care has completed. Secondary data use refers to purposes other than those for which consent was originally provided, such as research, is regulated differently23 and is vulnerable to privacy risks. A useful framework could consider how data is released for primary use, in ways that then reduce downstream risks from secondary use62. While regulations such as GDPR require data to be secured appropriately22, they do not recommend specific tools.

An alternative framework is a dynamic privacy model. Data access could be time-limited to fulfil a specific task, such as the acute care of an individual, and authorised for the care team. The types of accessible data could be minimized to reduce downstream risks of linkage attack, and time-limited for each stage that the patient reaches in a task. The system would be implemented to enable timely data utility while maintaining these privacy safeguards.

Here, we introduce a sample framework for health data privacy in which the primary unit of privacy is the biomedical task, that we reference to applicable privacy strategies. In Fig. 3, the privacy framework first assesses the specific task (primary axis), followed by axes of data type, the role of user(s), and the time bounds for data access.

Axis I: Task such as care of a given patient, resource analysis, or research. Axis 2: Data required for the specific task, and its progression from start to completion. Axis 3: User(s) who require access. Note that data owners (patients or consumers) should have unlimited rights of access. Axis 4: Length of time for which access is required, such as for acute care, after which it can be restricted. The framework can be used to design data release that, together with privacy-enhancing technologies, can minimize downstream privacy risks.

Primary axis I. Specific task

Health data tasks broadly span individual care, research and industry, that progress from start to completion. The task largely determines the approach to privacy—patient care requires data at the individual level and is well suited to privacy solutions that operate on encrypted data (e.g., homomorphic encryption, see section Privacy Engineering for Biomedical Data), but less suited to privacy solutions that operate on aggregated data (e.g., differential privacy, see section Privacy Engineering for Biomedical Data). While some tasks share attributes across domains, such as outpatient clinical care, others may differ substantially such as the processes followed by a geneticist versus a surgeon, or population versus patient-centred research, or to develop an app.

Axis II. Data type

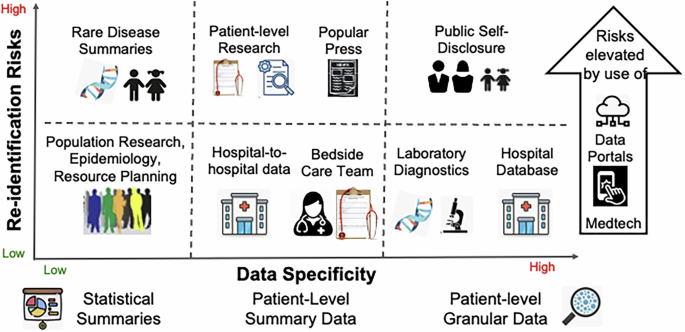

Differing types of data required for a task introduce different privacy threats. Fig. 4 breaks data types into categories of granular and aggregated data, although real-world cases may blend categories. Data needs will change as a task progresses from start to completion. Data types would have to be defined by experts in data science, with real-world experience in these tasks, and will require periodic review to incorporate changing practice patterns such as telehealth and crowdsourced data collection66.

Patient-level care or research may require granular data for laboratory diagnostics, although bedside care often uses only data in ranges rather than precise values (such as left ventricular ejection fraction). Population research and resource planning could use aggregate data, which introduce different and potentially lower risks. Re-identification risks are elevated by self-disclosure on social media and the growth of consumer diagnostics developed by private corporations, which are often not HIPAA-covered entities.

Granular Data

Granular data may uniquely identify an individual and carry substantial privacy risks. Such data may be required for patient care, medicolegal evaluation, patient-oriented research, and algorithmic development in industry. Examples include history and laboratory tests at a clinical encounter, sequences of X-ray images over time, or mutation-level genomic data. Another form of granular data includes sequences of billing data such as CPT codes.

Granular data, however, can be protected while preserving utility by techniques such as generalization. While a pathologist requires access to actual tissue to perform their task, and a radiologist requires access to granular images, bedside clinicians often make decisions on ‘reduced’ data. Clinicians may be satisfied with knowing a patient’s age in bands such as ’40 s’ rather than 41 or 47 years precisely, a cardiologist may be satisfied with knowing left ventricular ejection fraction in ranges such as ’35–50%’ rather its value to single digit precision, and a pulmonologist may rely on a tumour stage more than its precise histology or dimensions. This approach of reduced data release—of generalized rather than raw data even for primary use—has been shown to protect against privacy attacks in other domains when data is subsequently aggregated7,27,67,68.

Aggregate Data

Aggregate data may afford greater privacy protections than granular data because released elements are less specific25. This reduces the certainty that any particular record indicates a specific person, has a sensitive attribute or is a member of a specific group7,27,67,68. Aggregate data are widely used for tasks such as outcome tracking within a clinical unit, communications between healthcare providers and patients, population-based research, resource utilization, and public reporting of clinical trial data.

Axis III. Intended users

Intended users are straightforward for some use cases, such as the hospital team entrusted with caring for an individual, or related users such as subspecialty consultants. Others are less obvious, such as legal and compliance teams in clinical practice. Other users are controversial, including researchers or industry professionals developing an app. User roles may change over the natural history of a task.

Axis IV. Time bounds of data access

Data access should be limited to the time for each stage of a task. While the primary care team and consultants must have immediate data access at their point in care, access may later be restricted as appropriate. It may be reasonable for users to request longer time bounds, such as a consultant requesting continued access to a patients’ data for follow-up, or technology companies requesting extended access to update their AI models. These requests can be considered case-by-case. The Supplementary Materials illustrate use cases for the framework.

Comparison to other data use frameworks

In international human rights law, the Necessary and Proportionate Doctrine specifies that data collection is permissible provided it is necessary to serve a legitimate legal purpose, and is narrowly tailored to be proportionate for this purpose69. The World Health Organization extended this logic to public health priorities and taking appropriate measures to minimize disclosure risks70.

Underlying these approaches are the principles of data minimization71, to collect only the minimal viable amount of information for a given task, and purpose limitation, to collect and use information only for legitimate purposes72, which are referenced in Article 5(1)(c) of the European Union’s GDPR and California’s Privacy Rights Act (CPRA, Section 1798.100)73.

The proposed framework shares the goal of data minimization, integrated with PETs. It is intended to be used as a tool to identify the factors to consider for privacy needs, which can then help drive the selection and implementation of PETs for a task. The framework augments existing consenting and data-sharing processes but is not intended to replace them.

Implementation of such frameworks may introduce complexities for healthcare organizations and research institutions, which may be unavoidable. Task-based, user-specific and time-limited privacy is emerging elsewhere in professional life and society—in subscription-based access to online journal articles or movie content, in financial and legal transactions. Unlike current ‘break the glass’ policies that simply restrict data access behind digital firewalls, strategies such as that proposed here must be seamless for the user to avoid delays in utility. One may argue that current privacy solutions are less cumbersome, but it is unclear if they are adequate for emerging privacy threats. Future discussions on health data privacy frameworks must include data owners (ultimately, patients), ethicists, health care Institutions, research bodies, industry, legal experts and government.

Privacy engineering for biomedical data

Privacy engineering focuses on the design and implementation of solutions to data privacy threats17. Several technical solutions or privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) differ in their benefits and tradeoffs74, such as reduced data precision or increased computation time, and none offers a panacea as emphasised by Mulligan et al.55.

The selection of PETs for a given health data task is a developing field. While policies by organizations such as OECD (Organization of the Economic Co-operation and Development)75 emphasise health data privacy, they focus on traditional authentication and authorisation policies. Nevertheless, a consensus is emerging around the need to address emerging threats raised by AI and a plethora of data, and the United Nations recently adopted language by the US government on safe and reliable AI76.

We outline PETs that could be adapted to the health data ecosystem74, presenting preferred use cases as a foundation for appropriate use. Implementation of solutions is likely complex and will require interoperability between systems77. Table 1 summarizes various privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) (Fig. 5).

PETs have varying strengths and weaknesses and should be tailored to the specific task and data type. a Differential privacy generates processed data which are statistically indistinguishable from the raw population data, but cannot be used to infer details on any individual. b Homomorphic encryption enables analyses on encrypted data without first de-encrypting them and can be used for individual-level analysis. c Secure Multiparty Computation split access between users so that no one has access to the entire dataset, and may be valuable for distributed tasks such as clinical trials. d Federated learning integrates data from multiple sources to develop AI models. e Synthetic data have similar statistical properties to raw data but do not reveal individual properties.

Differential privacy (DP) is a mathematical strategy that guarantees, informally, that any outcome of a statistical analysis of a dataset is “essentially as likely” to occur regardless of an individual’s precise data point78. An adversary will thus not be able to discern from the output whether a specific individual’s data was included or not. When properly configured, differential privacy can thus prevent re-identification79, MIA in aggregated data12 and AI models12,46,80, differencing attacks40, training data extraction49, and model inversion51.

DP works by adding “carefully crafted noise” that introduces a privacy-accuracy tradeoff: the greater the noise the greater the privacy, yet the less useful the data. The precise loss of accuracy can be calibrated for a particular task78,81. DP has been applied for genomic analysis35, epidemiology81, and medical imaging82 and is more accurate on larger datasets78. The U.S. Census Bureau uses DP techniques when reporting public health data34, which serves as a model for institutions to publish aggregated data. Accordingly, DP may be better suited for population tasks than for individual patient care and is less suited for analyzing outliers such as specific critical laboratory values or effects in subsets of the population78,81.

While differential privacy addresses the motivating threats for this manuscript, other threats can also arise from the collection, sharing, and use of data in the health setting. We now considering several additional PETs.

Homomorphic encryption (HE). Encryption is frequently used to achieve health data privacy, yet typically requires data to be de-encrypted for analysis—during which time they are vulnerable to attack. HE is a mathematical approach that allows computations to be performed on encrypted data without decrypting them.

Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) enables a diverse array of computations, while partially homomorphic encryption (PHE) supports only certain operations including addition or multiplication. HE has been applied for individual patient care, such as developing genetic risk scores accessible for authorised providers by storing encrypted genetic (single nucleotide polymorphism) data and pseudonymized identifiers in separate processing facilities83. HE has also been used for gene-based cancer risk modelling84 and for coronary angiography85. The National Institutes of Health have funded iDASH (Integrating Data for Analysis, Anonymization, and Sharing) as a National Center for Biomedical Computing using HE to enable Institutions to conduct computations without de-encryption86. The tradeoff of HE tends to be that computation time is more burdensome than for unencrypted data. This may limit its application for mobile technologies87, or other applications or geographies where resources are constrained, but can be mitigated using partial HE.

Secure multiparty computation (SMC) enables decentralized computations without the need for a central data repository, by mathematically combining information such that nothing is revealed to data holders beyond what is revealed by the computational analysis. Several potential uses for SMC include analyses across institutions such as coordinating data for clinical trials, cancer research projects, population health management88, or population research on MRI features89. The tradeoffs in SMC are its logistical and computational complexity, which may limit its use in resource-constrained applications such as mobile digital technologies.

Federated learning (FL) describes the development of AI models using data from multiple sources. FL has been used to train AI models to identify diabetic retinopathy using optical coherence tomography scans from different scanners90 and to predict cardiovascular hospitalizations using electronic health records from multiple institutions91. Unlike SMC, the decentralized nature of federated learning does not offer a mathematical guarantee of protection by itself but, when paired with other techniques, federated learning can inherit their mathematical guarantees. For example, federated learning has been combined with SMC and HE to develop secure AI models for outcomes prediction in oncology and GWAS92, and with differential privacy to develop secure AI models for medical image analysis93.

Federated learning has limitations in the health setting. First, distributing data protection between centres may complicate alteration of access at any one center. Second, centres in a network may differ in key attributes, which may introduce diversity yet fall short of a key statistical requisite of samples being independent and identically distributed.

Synthetic data is an emerging approach to develop AI models or perform tasks that require a dataset rather than summary outputs, shielding the specifics of data while preserving their statistical properties94. Using a commercial service (MDClone) to generate synthetic data, Lun et al. showed that patients with ischaemic stroke with and without co-existing cancer differ in their prevalence of hypertension, chronic obstructive lung disease and thromboembolic disease, that was confirmed in actual clinical data95. Synthetic data offer no mathematical guarantee of privacy per se96 but can be paired with techniques such as differential privacy to train AI models97. A limitation of differential privacy synthetic data is that it may be difficult to preserve correlations between all variables in the original data, although preserving some correlations is achievable98. Other limitations include the types of data that can be synthesised, and whether they are realistic. AI models trained with synthetic data may have lower accuracy than those trained on real data99, albeit with higher privacy protection96.

Privacy engineering via accountability mechanisms

Data privacy breaches can be addressed by several mechanisms. Access controls aim to ensure that granular information is only available to approved individuals with a legitimate need for their task100. Privacy-preserving programming frameworks can be used to restrict the types of computations run or enforce that they are run in a privacy-preserving manner (e.g., using differential privacy)81. Controlled environments, such as data clean rooms101, trusted execution environments102, and secure research facilities can also be used to limit the misuse of data. For example, Dutch researchers developed a controlled environment to analyze vertically partitioned health data across multiple parties in a privacy-preserving manner103. Finally, audit logging can be used to monitor which individuals access information, and what types of computations they run71. While access controls and audit logging were originally developed for security purposes, their use has extended into modern data privacy practices to restrict the flow of information to appropriate individuals for appropriate use cases. Taken together, these mechanisms provide practical barriers to restrict improper information disclosure, by documenting when and how information was used and by whom.

Discussion and conclusions

The nature of privacy threats to health data is evolving. Traditional threats include cyber-attacks leading to the leak of personal data from healthcare entities, which are expanding to direct-to-consumer services. These growing threats challenge existing privacy practices and legislation for health data. In addition, emerging non-traditional privacy threats could have just as great an impact.

Diverse privacy threats can now occur without traditional data leakage, enabled by advances in artificial intelligence, aggregation of massive online data resources, and data analytics. While these technologies have advanced many facets of health care, they have removed some structural obstacles to privacy attacks—making them easier and more efficient to perform—and have introduced new risks. For instance, fully trained AI models and large language models that are emerging throughout medicine carry vestiges of training data, that could be used to infer sensitive characteristics of individuals used for training.

Such threats introduce new ethical and societal challenges, and a need for novel solutions that maintain privacy yet ensure data utility for critical health care tasks. A variety of privacy solutions are now available, some applicable to individual patients, such as homomorphic encryption, others better suited to population data, such as differential privacy, and others suited to maintain privacy between hospitals in a trial network, such as secure multiparty computation. Each has strengths and limitations, which can be considered as part of an integrated health data privacy framework.

Future initiatives on health data privacy must start with shared decision-making with the patient (data owner). This should be transparent, considering current and future data uses, types of data and what protections are available. This will require education of data owners, caregivers and health data professionals, so that truly informed decisions can be made. The subsequent implementation of privacy technologies is likely to be complex but is unavoidable and should include data owners, ethicists, health care Institutions, research bodies, industry, legal experts and government.

Responses