Addressing unexpected bacterial RNA safety concerns of E. coli produced influenza NP through CpG loaded mutant

Introduction

Influenza A virus (IAV) is a highly contagious zoonotic pathogen that poses a significant threat to global public health1. Current seasonal influenza vaccines mainly work by inducing neutralizing antibodies that target the immunodominant head region of HA2,3,4, which frequently undergoes antigenic changes. Therefore, the pre-established immune protection against newly emerging influenza strains is limited5,6,7. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop a universal influenza vaccine that protects against multiple strains using antigens conserved among different influenza strains.

The nucleoprotein (NP) is one of the conserved antigens that has been a popular antigen target for universal influenza vaccine development. It contains conserved immunodominant CD8+ T cell epitopes that can induce cellular immune responses to eliminate the virus-infected cells8,9,10,11. The recombinant NP protein, usually produced in E. coli, is highly immunogenic and induces complete or partial protection against divergent influenza viruses in the absence of adjuvants12,13,14. The immune protection of NP could be further improved by rational design, for example by presentation of NP antigen as nanoparticles15,16 and by addition of adjuvant12,17. In addition, the inclusion of the other conserved antigens of influenza virus, such as the ectodomain of the M2 protein (M2e), M1, and the conserved region of HA, can also increase the protective efficacy and broaden the protective spectrum of NP vaccines16,18,19,20,21.

NP plays a critical role in the replication and assembly of influenza viruses22. It binds influenza viral RNA (vRNA) to form the vRNP complex23,24, probably through its five arginine residues (at positions 74, 75, 174, 175, and 221)25. Previous studies have shown that the recombinant NP protein can bind the synthetic short RNA26,27. However, there are no direct evidences that the recombinant NP protein binds bacterial RNA during its production in E. coli. Since the recombinant NP proteins are highly immunogenic in the absence of adjuvants, it is interesting to know whether E. coli-produced NP proteins bind bacterial RNAs and how these RNAs affect the immune response to NP.

In this study, we found that the recombinant NP proteins produced in E. coli contained bacterial RNAs bound to them. Removal of these RNAs almost completely abolished the NP-specific immune responses in mice in the absence of adjuvant. Although the E. coli RNA can enhance the NP-specific immune responses, we found that the bacterial RNA bound to NP varied significantly among different NP preparation batches, affecting the uniformity of the vaccine. Since the immunostimulatory effect of bacterial RNA is dose-dependent, higher doses could potentially trigger systemic inflammation and related adverse immunopathology, raising safety concerns. For this purpose, we developed a NP mutant with the CpG1826 (a synthetic oligodeoxynucleotide widely used as an adjuvant for vaccines) but without the bacterial RNA binding activity. CpG1826-loaded NP induced similar protection as the E. coli RNA-bound recombinant NP protein, and CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut induced enhanced protection against influenza viruses challenge. Our study not only highlighted the safety concerns of the E. coli-produced NP protein, but also provided an NP mutant as a potent target for the development of universal influenza virus vaccines.

Results

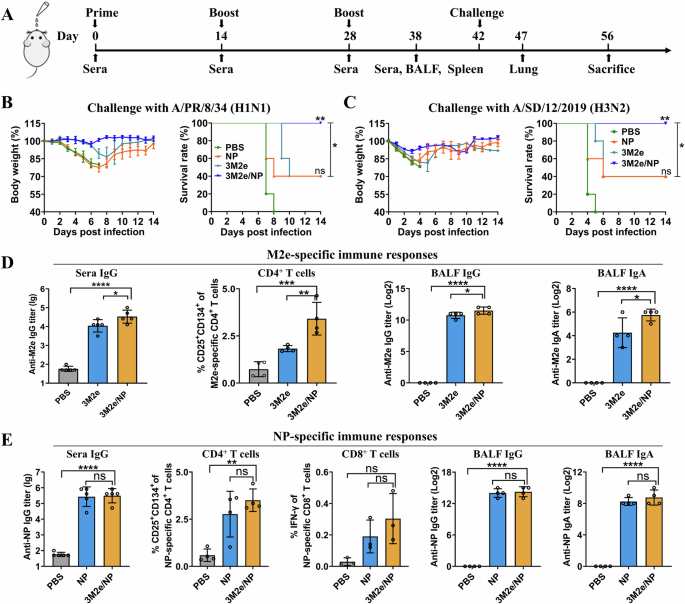

Coadministration of NP enhanced the 3M2e-specific immune responses

Our initial goal was to develop a universal mucosal vaccine containing both NP and M2e antigens. The NP and 3M2e proteins produced in E. coli were intranasally administered to mice in the absence of exogenous adjuvants three times at 14-day intervals as shown in the schematic (Fig. 1A). Control mice were immunized with the same dose of NP, 3M2e, or with the same volume of PBS, respectively. 3M2e/NP provided 100% protection against challenge with A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (Fig. 1B) or A/SD/12/2019 (H3N2) (Fig. 1C) 2 weeks after the last immunization, while NP and 3M2e alone provided only 40% protection. Changes in mouse body weight also showed the same trend that 3M2e/NP provided better protection than NP and 3M2e alone (Fig. 1B, C).

A Scheme of the mouse experiment. Mice were immunized three times, and sera and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were collected to determine the antigen-specific antibodies. Splenocytes were collected for analysis of cellular immune responses. Lung tissue was collected for histopathological analysis. Mice (n = 5) were challenged with 5 × LD50 of A/PR/8/34 (B) and 2.75 × LD50 of A/SD/12/2019 (C) 2 weeks after the last immunization. Weight loss and survival rate were monitored daily for 14 days. The statistical significance of survival curves was determined by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. ns: PBS versus NP, **PBS versus 3M2e/NP, *NP versus 3M2e/NP. M2e-specific (D) and NP-specific (E) immune responses were determined as described in the Materials and Methods (n = 3 to 5 per group). Data were shown as mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001, respectively (ANOVA).

Interestingly, we found that the levels of M2e-specific IgG in sera, CD4+ T cells and levels of mucosal IgG and IgA antibodies in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were significantly increased in the 3M2e/NP group compared to the 3M2e group (Fig. 1D). While there are no significant differences in the levels of NP-specific IgG, T cells, and mucosal immune responses between the 3M2e/NP and NP groups (Fig. 1E). The PBS control groups showed only negligible antigen-specific immune responses. Taken together, these results showed that co-administration of NP enhanced the 3M2e-specific immune responses, indicating the adjuvant activity of NP on 3M2e.

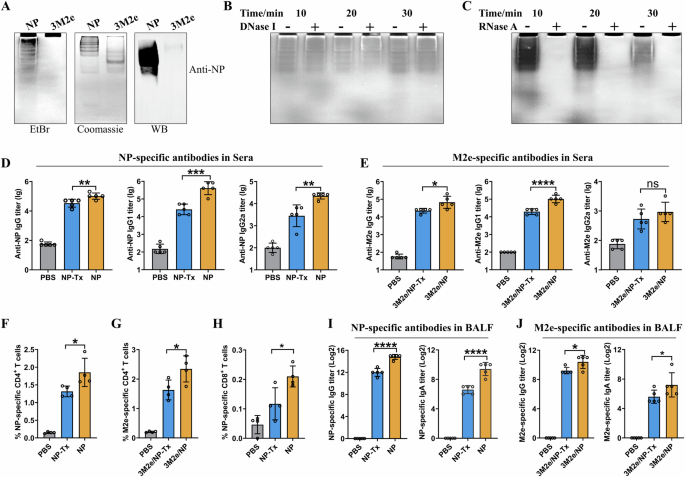

The adjuvant activity of NP on 3M2e relies on the NP-bound E. coli RNA

Low levels of E. coli endotoxins can stimulate inflammatory reactions and enhance the immune responses28,29. However, we found that the endotoxin levels in the purified recombinant NP and 3M2e proteins were very similar (2.3 and 2.1 EU/ml, respectively), indicating that the adjuvant activity of NP was not due to the residual endotoxin contamination. This led us to question whether the recombinant NP proteins contain E. coli nucleic acids, which may have immune-enhancing activity30. Therefore, we determined the nucleic acids in the purified proteins using non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and found that the NP protein, but not the 3M2e, contained a large amount of bacterial nucleic acids (Fig. 2A). DNase I and RNase A treatments suggested that the nucleic acid was RNA (Fig. 2B, C).

A Non-denaturing PAGE showed that the NP protein, but not the 3M2e, contained bacterial nucleic acids. The nucleic acids and proteins were stained with EtBr and Coomassie blue, respectively. Recombinant NP was further confirmed by western blot using anti-NP serum. RNase-free DNase I (B) and DNase-free RNase A (C) treatments suggested that the recombinant NP proteins contained E. coli RNA. D–J The adjuvant activity of NP on 3M2e relies on the NP-bound E. coli RNA. Mice were immunized as shown in Fig.1A, and NP-specific (D) and M2e-specific (E) antibody titers in sera were shown. NP-specific (F) and M2e-specific (G) CD4+ T cells, and NP-specific CD8+ T cells (H) were determined as described in the Materials and Methods. I, J showed NP-specific and M2e-specific antibody titers in BALF, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± S.D, n = 4–5 mice for each group. “ns” indicates not significant. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001, respectively (ANOVA).

Bacterial RNAs act as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that trigger innate immune responses by activating transcription factors such as NF-κB and interferon regulatory factor (IRF)31,32. Using NF-κB-Luc and IRF3-Luc dual-luciferase reporter assays, we showed that NP-bound bacterial RNA could activate NF-κB and IRF3 in a dose-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 1). These results suggested that NP-bound bacterial RNA may be a key factor in enhancing the 3M2e-specific immune responses, probably by activating innate immune responses.

To investigate whether the bacterial RNA enhances the antigen-specific immune responses, the purified NP proteins were first treated with Benzonase nuclease to remove bacterial RNA (NP-Tx) and used to intranasally immunize mice with or without 3M2e according to the schedule as shown in Fig. 1A. Mice immunized with NP, a mixture of NP and 3M2e, or PBS were used as negative controls. ELISA results of the sera collected 10 days after the last immunization showed that the levels of the NP-specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a were significantly lower in the NP-Tx group compared with the NP group (Fig. 2D). The lower levels of M2e-specific IgG and IgG1 antibodies were also detected in the 3M2e/NP-Tx group compared to the 3M2e/NP group (Fig. 2E).

Similarly, cellular immune response analysis showed that NP-Tx induced a lower level of NP-specific CD4+ T cell responses compared to NP (Fig. 2F), and 3M2e/NP-Tx induced a lower level of M2e-specific CD4+ T cell responses compared to 3M2e/NP (Fig. 2G). Similar results were also observed for the CD8+ T cell responses, with the NP-Tx-immunized group showing lower levels of NP147-155-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells compared to the NP-immunized group (Fig. 2H).

We also observed a similar declining trend when analyzing the levels of antigen-specific IgG and IgA in BALF. NP-Tx and 3M2e/NP-Tx induced significantly lower levels of specific IgG and IgA than the corresponding untreated groups (Fig. 2I, J). The PBS-vaccinated group did not induce any antigen-specific IgG and IgA antibodies.

Previous studies have shown that oligomeric forms of protein antigens are more immunogenic than the monomeric forms33,34. To determine whether removal of bacterial RNA affects the oligomeric state of NP, leading to the difference in NP immunogenicity, we analyzed NP and NP-Tx by size exclusion chromatography. The results showed that oligomeric state of NP and NP-Tx were the same, and both were eluted mainly as three peaks (Supplementary Fig. 2). Combining with animal experiment data (Fig.2), these results indicate that NP-bound bacterial RNA has adjuvant activity, which may be the main reason for the enhanced 3M2e-specific immune responses.

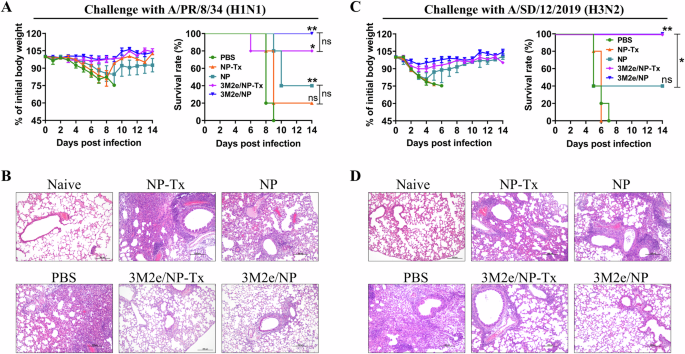

The NP-bound E. coli RNA enhanced the efficacy of the NP/3M2e vaccine

To determine whether bacterial RNA enhances protective immunity, mice were challenged with a lethal dose of H1N1/PR8 virus 14 days after the last immunization (Fig. 3A). There was no significant change in the body weight of mice in the 3M2e/NP-immunized group, while all the other four groups of mice showed varying degrees of weight loss. Mice immunized with NP-Tx had a 20% survival rate, while those immunized with NP had a 40% survival rate. Mice immunized with 3M2e/NP-Tx had an 80% survival rate, while those immunized with 3M2e/NP had a 100% survival rate. As expected, all mice immunized with PBS died within 9 days after the challenge (Fig. 3A).

Mice were immunized as shown in Fig. 1A, and challenged with influenza virus on day 42 post-vaccination. Weight loss and survival rate of mice (n = 5) were monitored daily for 14 days after challenged with 5 × LD50 of A/PR/8/34 (A). The statistical significance of survival curves was determined by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. ns between PBS and NP-Tx, ** between PBS and NP, ** between PBS and 3M2e/NP, * between PBS and 3M2e/NP-Tx, ns between 3M2e/NP-Tx and 3M2e/NP, ns between NP-Tx and NP. Lungs (n = 3) were collected at 5 dpi for pathological analysis (B). Weight loss and survival rate of mice (n = 5) were monitored daily for 14 days after challenged with 2.75 × LD50 of A/SD/12/2019 (C). The statistical significance of survival curves was determined by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. ns between PBS and NP, ** between PBS and 3M2e/NP, * between NP and 3M2e/NP. Lungs (n = 3) were collected 4 dpi for pathological analysis (D). Representative results from each group were shown. Scale bars, 200 µm.

For histopathological analysis, in another set of animal experiments, lung tissues were collected from immunized mice on day 5 post-challenge (Fig. 3B). The mice in the NP-Tx groups showed severe lung damage, including the unclear lung structure, obvious thickening of the alveolar wall, and severe inflammatory cell infiltration compared with the mice in the NP group (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 3A). Similarly, the mice in the 3M2e/NP-Tx group also showed less severe lung damage compared with NP-Tx group, while the 3M2e/NP group showed normal histological morphology of the lung tissue (Fig. 3B).

When challenged with a lethal dose of H3N2 influenza virus, the survival rate of mouse in the NP-Tx group was significantly lower than that of the NP group (Fig. 3C). The survival rate of mice in the 3M2e/NP-Tx group was the same as that in the 3M2e/NP-immunized group, but the pathological features were more obvious than this in the 3M2e/NP-immunized group (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Fig. 3B). Taken together, these results indicate that the NP-bound E. coli RNA has adjuvant activity and enhances the protective efficacy of NP/3M2e vaccine.

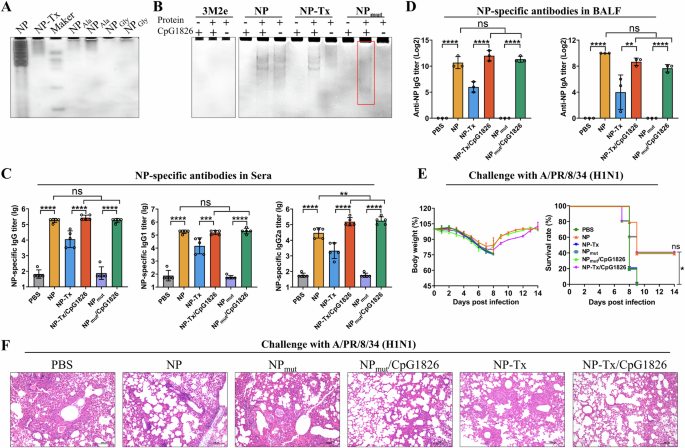

An NP mutant with the CpG1826 but without the bacterial RNA binding activity as a target for universal influenza vaccines

Although NP-bound E. coli RNAs can enhance immune responses, we found that the bacterial RNAs were not homogeneous and their amount bound to NP varied significantly from batch to batch (Supplementary Fig. 4). Bacterial RNA is a potent inducer of type I IFN and NF-κB-dependent cytokines, and it can also activate the Nlrp3 inflammasome35. Since their immunostimulatory effect is dose-dependent (Supplementary Fig. 1), higher doses of bacterial RNA could potentially trigger systemic inflammation and related adverse effects, raising safety concerns and the risk of undesired immunopathology. Therefore, we aimed to eliminate the bacterial RNA binding activity of the recombinant NP. Recent studies have shown that residues R74, R75, R174, R175, R221 of NP are important for its RNA binding26. Therefore, we first generated 2 five-point mutants of NP, in which these arginine residues were mutated to either alanine (NPAla) or glycine (NPGly) (Supplementary Fig. 5A), to determine their E. coli RNA binding activity. The protein-bound RNA was analyzed by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and quantified using grayscale intensity analysis with Image-Pro Plus software. The results showed that grayscale intensity value of NP-bound RNA was ~4.35, 7.71, and 45.70 times higher than that of NP-Tx, NPAla, and NPGly-bound RNA, respectively (Fig. 4A). These results indicated that mutation of all these five arginines to glycine (NPGly) almost abolished the E. coli RNA binding activity of the recombinant NP. Therefore, NPGly (referred to as NPmut in the following studies) was purified in large amounts and used in the following experiments (Supplementary Fig. 5B).

A Non-denaturing PAGE showed that the NP mutant (arginine mutates into glycine) lose the E. coli RNA binding activity. The RNase A-treated (NP-Tx) and untreated (NP) wild-type recombinant NP proteins were used as controls. The gel was stained with EB. B Non-denaturing PAGE showed that the recombinant NPmut proteins could bind CpG1826 (highlighted in red box). NP, NP-Tx, and 3M2e were used as controls. C, D Co-delivery of CpG1826 enhanced the immune responses against NPmut. Mice were immunized as shown in Fig. 1A. NP-specific total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a in sera (C) (n = 5), and NP-specific IgG and IgA in BALF (D) (n = 3) were measured by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. **, ***, and **** indicate p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and P < 0.0001, respectively (ANOVA). Two weeks after the last immunization, mice were challenged with 5 × LD50 of A/PR/8/34. Body weight and survival rate of mice (n = 5) were monitored daily for 14 days (E). The statistical significance of survival curves was determined by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. * between PBS and NP, ns between NP, NP-Tx/CpG1826 and NPmut/CpG1826. Lungs (n = 3) were collected 4 days after challenge for histopathologic analysis (F). Scale bars, 200 µm.

Although the NPmut does not efficiently bind E. coli RNA in vivo, we are curious whether it could bind RNA/DNA in an in vitro reaction system (high concentrations of protein and RNA/DNA). Since poly(I:C) and CpG are two well-known molecular adjuvants with known mechanisms of action36, we determined their binding activity to the NPmut. The results showed that the NPmut can bind CpG1826 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 6A), but not the poly (I:C) (Supplementary Fig. 6B). The binding of CpG1826 to NPmut was further confirmed by size exclusion chromatography, where NPmut alone was eluted as a single peak corresponding to the monomer (Supplementary Fig. 7A). When incubated with CpG1826, NPmut was eluted as two peaks (Supplementary Fig. 7B). Non-denaturing PAGE and PAGE analysis showed that both peaks contained CpG1826 and NPmut (Supplementary Fig. 7D and 7E). In addition, dynamic light scattering (DLS) results also indicated that CpG binds to NPmut and formed a larger complex (Supplementary Fig. 7F), which is consistent with the size exclusion chromatography data. These results indicate that the CpG1826-binding NPmut not only resolves the safety concerns caused by E. coli RNA contamination, but also enables the co-delivery of antigen and adjuvant.

To evaluate whether the co-delivery of CpG1826 enhances the immune responses of NP, mice were immunized intranasally with NPmut or CpG1826-loaded NPmut in the absence of additional adjuvants as shown in Fig. 1A. The NP, NP-Tx (Benzonase nuclease treated), the mixture of NP-Tx and CpG1826, and PBS were used as controls. The ELISA results of the sera collected 10 days after the last immunization showed that the NPmut induced negligible NP-specific antibody responses compared to the PBS control (Fig. 4C). This indicates that the adjuvant activity of the NP-bound E. coli RNA is necessary for the NP-specific immune responses, which is further supported by the levels of NP-specific antibodies between NP and NP-Tx groups. However, the NP-Tx is more effective in inducing NP-specific antibodies than the NPmut (Fig. 4C), which may be due to the residual of E. coli RNA in the NP-Tx even after Benzonase nuclease treatment (Fig. 4A). Co-delivery of CpG1826 significantly increased the levels of the NP-specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a compared to the NPmut group (Fig. 4C). Simple mixing of CpG1826 with NP-Tx can also enhance the levels of the NP-specific antibodies. Similar results were observed for NP-specific IgG and IgA antibodies in BALF (Fig. 4D).

Influenza virus challenge experiments showed that mice immunized with PBS, NPmut, and NP-Tx respectively began to lose their weight on day 3, and no mice survived on day 9 after the challenge (Fig. 4E). In contrast, 40% of mice immunized with either NP, NPmut/CpG1826, or NP-Tx/CpG1826 respectively survived (Fig. 4E). In another set of challenge experiments, lung tissues were collected from immunized mice on day 4 post-challenge for histopathological analysis. The results showed that mice in the NPmut/CpG1826, NP-Tx/CpG1826, and NP groups had less pathological damage and inflammatory cell infiltration compared to the NPmut, NP-Tx, and PBS groups (Fig. 4F and Supplementary Fig. 8).

Taken together, these results demonstrated that the NPmut addressed the safety concerns of E. coli RNA contamination and enabled the co-delivery of antigen and adjuvant (CpG1826) to induce similar immune responses. It therefore represents a potential target for the development of universal influenza vaccines.

Codelivery of CpG1826 enhanced the efficacy of NPmut/3M2e

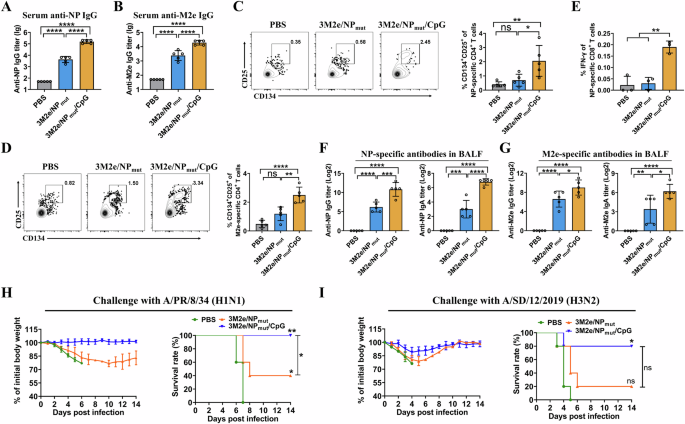

To determine the potential of CpG1826-loaded NPmut as a component for the bivalent influenza vaccines, 3M2e proteins were mixed with NPmut or CpG1826-loaded NPmut and used to immunize mice intranasally in the absence of additional adjuvants as shown in Fig. 1A. PBS was used as a control. Sera were collected on day 38, and antigen-specific IgG antibody titers were analyzed by ELISA. The results showed that co-delivery of CpG1826 significantly increased the levels of the NP-specific IgG (Fig. 5A. CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut versus to the 3M2e/NPmut). Similarly, the M2e-specific IgG were also significantly increased (Fig. 5B).

Mice were immunized as shown in Fig.1A. NP-specific IgG (A) and M2e-specific IgG (B) were determined by ELISA (n = 5). NP-specific CD4+ T cells (C) and M2e-specific CD4+ T cells (D) were determined by activation-induced marker assay (n = 5). NP-specific CD8+ T cells (E) were determined by intracellular cytokine staining assay (n = 3). F NP- specific IgG and IgA in BALF (n = 5). G M2e-specific IgG and IgA in BALF (n = 5). Data are presented as mean ± S.D. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns, not significant (ANOVA). Mice (n = 5) were challenged with 5 × LD50 of A/PR/8/34 (H) and 2.75 × LD50 of A/SD/12/2019 (I) 2 weeks after the last immunization. Weight loss and survival rate were monitored daily for 14 days. Statistical significance of survival curves was determined by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. H * between PBS and 3M2e/NPmut, ** between PBS and 3M2e/NPmut/CpG1826, * between 3M2e/NPmut and 3M2e/NPmut/CpG1826. I ns between PBS and 3M2e/NPmut, * between PBS and 3M2e/NPmut/CpG1826, ns between 3M2e/NPmut and 3M2e/NPmut/CpG1826.

To evaluate whether CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut could enhance the antigen-specific cellular immune responses, splenocytes were isolated 10 days after the third vaccination. Antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses were determined by T cell receptor (TCR)-dependent activation-induced marker (AIM) assays, which have been widely used to identify antigen-specific CD4+ T cells37. The results showed that CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut induced higher levels of NP-specific CD4+CD25+CD134+ T cells compared to 3M2e/NPmut (Fig. 5C). Similarly, the levels of M2e-specific CD4+CD25+CD134+ T cells were significantly increased in the CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut group than those in the 3M2e/NPmut group (Fig. 5D). The NP-specific CD8+ T cell responses were determined by intracellular cytokine staining assay using a CD8+ T cell epitope peptide of NP. The results showed that the percentage of IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells in the CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut group was significantly higher than that in the 3M2e/NPmut group (Fig. 5E and Supplementary Fig. 9).

To evaluate whether co-delivery of CpG1826 3M2e/NPmut could enhance mucosal humoral immune responses, the levels of antigen-specific mucosal IgG and IgA in BALF were measured by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 5F, G, the CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut group showed higher levels of antigen-specific IgG and IgA responses compared to the 3M2e/NPmut group. As expected, no M2e- or NP-specific IgG and IgA antibodies were detected in the PBS control group.

Challenge data showed that the body weights of mice in the PBS and 3M2e/NPmut groups began to decrease 2 days after the challenge whereas the mice in the CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut group didn’t (Fig. 5H). CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut induced complete protection against A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) challenge, whereas 3M2e/NPmut provided 40% protection. As expected, no mice survived in the PBS control group (Fig. 5H). Similarly, when mice were challenged with A/SD/12/2019 (H3N2) influenza virus, we found that CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut provided enhanced immune protection compared to 3M2e/NPmut (Fig. 5I). These results indicated that CpG1826 not only enhanced NP-specific immune responses, but also increased M2e-specific immune responses.

Discussion

Our study provided important insights into the immunogenicity of recombinant NP produced in E. coli, a popular antigen used in the development of universal influenza vaccines. We found that the high immunogenicity of the E. coli-produced NP protein is largely due to the presence of bacterial RNA bound to the NP during production. These E. coli RNAs significantly enhance NP-specific immune responses, but their variability between different production batches may pose significant safety and consistency concerns for vaccine development.

Previous studies have shown that recombinant NP protein can bind the synthetic short RNA26. Our findings extend this knowledge by demonstrating that recombinant NP produced in E. coli also binds bacterial RNA, which acts as an adjuvant to enhance immune responses. This observation is consistent with the known role of PAMPs such as bacterial RNA in activating innate immune responses via receptors such as TLR935,38. Similar findings were also reported that trace amounts of bacterial RNA bound to the arginine-rich domain of the hepatitis B core antigen facilitated the priming of immune responses30, underscoring the potent adjuvant effect of E. coli RNA bound to recombinant antigens. An interesting finding of our study is that bacterial RNA bound to NP enhances the immunogenicity of the co-administrated M2e antigen.

However, the significant variation in bacterial RNA content between different batches of E. coli-produced NP poses a challenge for vaccine consistency because the immunostimulatory effect of bacterial RNA is dose-dependent (Supplementary Fig. 1). Although we did not directly evaluate the influence of the amount of bacterial RNA on the immunogenicity of NP using different NP batches, the difference in immunogenicity between NP (containing more bacterial RNA) and NP-Tx (containing residual amounts of bacterial RNA (Fig. 4A)) indicated that the amount of bacterial RNA affected the immunogenicity of NP (Fig. 2). In addition, higher doses of bacterial RNA could potentially trigger systemic inflammation and related adverse effects, leading to potential safety concerns27. To address these issues, we developed an NP mutant (NPmut) that lacks the RNA binding activity of the native NP but can be loaded with the synthetic adjuvant CpG1826. The CpG also enhances immune responses by activating TLR939 and has been approved by the FDA as an adjuvant for the hepatitis B vaccine (HEPLISAV-B)40. Our results demonstrate that the CpG1826-loaded NPmut induced immune responses comparable to those elicited by the E. coli RNA-bound NP, thereby maintaining immunogenicity while eliminating the safety risks associated with bacterial RNA contamination. In addition, CpG1826-loaded NPmut allows co-delivery of antigen and adjuvant to the same APCs, which may improve antigen uptake and enhance the immune responses as reported in previous studies41,42. Furthermore, the CpG1826-loaded 3M2e/NPmut provided enhanced complete protection against influenza viruses challenge, underscoring its potential as a robust component for universal influenza vaccines.

In conclusion, we have revealed the reasons for the high immunogenicity of E. coli-produced NPs and the corresponding safety concerns. We have provided direct evidence showing that E. coli-produced NP proteins bind bacterial RNAs, which significantly enhance NP-specific immune responses. However, the variability of bacterial RNA content between different production batches may pose significant safety and consistency concerns for vaccine development. By developing a NP mutant that lacks the bacterial RNA binding activity but can be loaded with CpG1826, we have addressed these safety concerns while maintaining the immunogenicity of the NP protein. The CpG1826-loaded NPmut represents a potent target for the development of universal influenza vaccines, providing a reliable approach to achieve broad and consistent immune protection against diverse influenza strains.

Methods

Plasmid construction

A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (GenBank accession number EF467822) was used to amplify the full-length NP gene, which was cloned into the pET28a expression vector to generate the pET28a-NP expression plasmid. Plasmids pET28a-NPAla and pET28a-NPGly, in which the arginine residues at sites 74, 75, 174, 175, and 225 were mutated to alanine and glycine, respectively, were constructed by site-directed PCR mutagenesis. Briefly, the primers carrying the desired point mutations were designed and used to amplify NP mutant fragments using pET28a-NP as a template. The PCR products were then cloned into the pET28a expression vector. The plasmid pRbSoc-3M2e expressing the three tandem copies of the ectodomain of the influenza M2 protein fused to the RbSoc gene was constructed in a previous study43.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

The expression plasmids pET28a-NP, pET28a-NPAla, pET28a-NPGly, and pRbSoc-3M2e were individually transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3), and protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 4 h at 28 °C. E. coli cells were collected by centrifugation at 4300 g for 15 min, resuspended in 100 ml of binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole), and lysed using a high-pressure cell disruptor. After centrifugation at 35,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.22 µM filter. The recombinant proteins were purified using HisTrap columns (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) and further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Hi-Load 16/60 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare Life Science) in GE buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 and 100 mM NaCl). To remove the NP-bound nucleic acid, the purified NP proteins were treated with DNase I, RNase A, or Benzonase nuclease without His-tag (250 U/mL) as indicated in the results. The treated NP was purified using HisTrap column as described above to remove the nuclease. The protein concentration was measured by SDS-PAGE using BSA as a standard. Endotoxin levels of purified recombinant proteins were determined using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) Endotoxin Quantitation Kit (Xiamen Bioendo Technology Co., Ltd, Xiamen, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot

Purified NP and 3M2e proteins were electrophoresed on a 6.5% native polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk for 2 h at 37 °C, the PVDF membrane was incubated with anti-NP polyclonal antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After three washes with TBST (Tris-buffered saline containing 1% Tween-20), the PVDF membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG for 45 min at room temperature. Protein bands were detected with ECL reagent using ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

Purification of NP-bound E. coli RNA

The purified NP protein was incubated at 98 °C for 8 min and then at 50 °C for 3 min to denature the NP and release bound E. coli RNA. The denatured NP proteins were pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant containing the released E. coli RNA was collected and subjected to gel electrophoresis. The target RNA band was excised and recovered using a gel extraction kit. The purified RNA was dissolved in pure water, and its concentration was determined using a spectrophotometer.

Luciferase reporter assays

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded into 48-well plates (2 × 104 cells/well) and cultured for 16 h to 60% confluency. Cells were transfected with pNF-κB-Luc (0.1 µg) or pIRF3-Luc (0.1 µg) reporter vector together with pRL-TK (0.01 µg) control vector using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 24 h of transfection, the cells were washed once with PBS and incubated with different concentrations of NP-bound bacterial RNA for another 12 h. Cells treated with LPS and poly(I:C), respectively, were used as positive controls. The cells were then washed three times with PBS and lysed with lysis buffer for 20 min. The activity of NF-κB and IRF3 was measured using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Promoter activity was calculated as the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase and expressed as the relative light units (RLU).

Gel-shift assay

Fifteen µg of each of the wild-type NP (nuclease treated and untreated) and the NP mutants (NPAla and NPGly) were loaded onto 6.5% native polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed in 0.5 × TBE at 4 °C for 1.5 h. The gels were then stained with EtBr for 20 min and imaged using Gel Doc XR+ documentation. The NP-, NPAla-, NPGly-, and NP-Tx-bound RNA were quantified by measuring the grayscale intensity of the corresponding bands using Image-Pro Plus software. To determine the binding activity of NP mutants to poly (I:C) and CpG1826, different amounts of poly (I:C) and CpG1826 were incubated with NP mutants individually in a 20 µL of Gel-Shift binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol). After 30 min incubation at 25 °C, the reaction mixtures were loaded onto 6.5% native polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed in 0.5 × TBE at 4°C for 1.5 h. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr) for 20 min and imaged using the Gel Doc XR+ documentation system (Bio-Rad).

Mice, immunization and influenza A virus challenge

The 6–8 week-old female BALB/c mice were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of Huazhong Agricultural University (Hubei, China). All animal experiments were performed after approval by the Animal Protection and Ethics Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University, China (HZAUMO-2023-0190). Mice were intranasally immunized three times with 15 µg of antigen (3M2e, NP, NP-Tx, NPmut, and CpG1826-loaded NPmut, respectively) per dose. Three µg of CpG1826 was loaded onto 15 µg of NP and used for each injection based on previous study showing that 1–10 of CpG can significantly boost the immune responses44. For bivalent vaccines, 15 µg of 3M2e was mixed with 15 µg of NP (NP, NP-Tx, NPmut, and CpG1826-loaded NPmut, respectively) and administered intranasally to the mice. Mice immunized with the same volume of PBS were used as negative controls. Sera were collected on days 0, 14, 28, and 38 to determine antigen-specific IgG antibody titers by ELISA. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected on day 38 by flushing the lungs three times with 1 mL of PBS to analyze the antigen-specific IgG and IgA antibodies. Splenocytes were also collected on day 38 for analysis of cellular immune responses.

For challenge, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and intranasally infected with A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) (A/PR/8/1934 (H1N1), accession numbers: EF467817-EF467824) or A/Shandong/12/2019 (H3N2) influenza virus (A/SD/12/2019 (H3N2), accession numbers: OK104799-OK104806) 2 weeks after the last immunization in 50 μL PBS. Mice were monitored for the body weight and mortality for 14 consecutive days. Mice with more than 25% weight loss were humanely euthanized by cervical dislocation under deep anesthesia with isoflurane and recorded as dead in accordance with animal ethics guidelines.

Lung histopathology

Lung tissues from immunized mice (n = 3) were collected on day 5 after challenge with A/PR/8/1934 (5LD50) or on day 4 after challenge with A/SD/12/2019 (3LD50) influenza virus. Lung samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 µm) were prepared, stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and observed with an optical microscope (Nikon, Japan). Pathological changes in the lungs were scored based on severity and inflammation around the lung bronchi, pulmonary blood vessels and alveolar wall, using a severity scale of 0–5 (none, minimal, mild, moderate, marked, and severe).

Antibody detection in serum and BALF

Antigen-specific antibodies in the serum (IgG, IgG1, IgG2a) and BALF (IgA and IgG) were measured by ELISA as previously described45. Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with 200 ng/well of purified NP protein or with synthesized peptide pool consisting of equal amounts of human, swine, and avian influenza M2e peptides overnight at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with 200 µL PBS containing 3% BSA for 1 h at 37 °C. After 5 washes with PBST (0.05% Tween-20 in PBS), 2-fold serially diluted sera or BALF were added to the plate and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After 5 washes with PBST, the plate was incubated with 100 µL of secondary antibodies (HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, or IgA) for 1 h at 37°C. After 5 washes with PBST, 100 µL of TMB substrate was added to each well for color development, and 100 µL of 2 M H2SO4 solution was added to stop the reaction. Finally, the absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader. The antibody endpoint titers were defined as the highest dilution of each serum sample for which the OD 450 exceeded at least twice the average blank control value.

Antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses

Activation-induced marker (AIM) assay was used to analyze antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses by assessing the upregulation of CD25 and CD134 as previously described37. Briefly, 1 × 106 splenocytes were cultured with a peptide pool containing equal amounts of human, swine, and avian influenza M2e peptides or NP55–69 peptide (RLIQNSLTIERMVL) (final concentration, 10 µg/mL) for ~45 h in 24-well plates. Cells were then collected, washed with RPMI1640 medium, and resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS with 3% FBS). For cell surface marker staining, cells were blocked with anti-CD16/32 antibody (S17011E, Biolegend) for 15 min and then stained with marker-specific antibodies, including anti-CD3-APC/Cy7 (clone 17A2, Biolegend), anti-CD4-FITC (clone GK1.5, Biolegend), anti-CD25-APC (clone PC61, Biolegend), anti-CD134-PE (clone OX-86, Biolegend) for 20 min at 4 °C in the dark. Cells were then washed three times with 2 mL FACS buffer and resuspended in 300 µL FACS buffer. To discriminate Live/dead cells, 1 µg/mL DAPI (BD Biosciences) was added to the samples before running the samples on the flow cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software, version 10.8.1.

Intracellular cytokine staining (ICCS) assay

Splenocytes were seeded to 24-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) and cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cells were then stimulated with 20 µg/mL peptide NP147–155 (TYQRTRALV) or with cell activation cocktail (BioLegend) as positive controls. Three hours after stimulation, 5 µg/mL Brefeldin A was added to block cytokine secretion, and cells were incubated for an additional 13 h. Cells were then washed, blocked with anti-CD16/32 antibody, and surface markers were stained with FITC-labeled CD3-specific mAb (clone 17A2, BioLegend) and PE-CD8a-specific mAb (clone 53-6.7, Biolegend). Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with IFN-γ-APC (clone XMG1.2, Biolegend) for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. After two washes with Perm Wash Buffer, cells were resuspended in FACS buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8. Multi-group comparisons were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All data are presented as the mean ± SD of at least three replicates, and p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical significance of survival curves was determined by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Responses