Adoption of full-culm bamboo as a mainstream structural material

Motivation: a greener construction sector

There exists a litany of publications and statistics demonstrating that the built environment is the dominant contributor of emissions driving the Global Climate Emergency. In 2023, the United Nations Environmental Programme1 identified the building sector as accounting for 37% of global CO2 emissions; approximately one quarter of which are associated with construction materials production. The construction sector extracts an estimated 50 billion tonnes of sand annually; a rate that is unsustainable and has wide reaching impacts2. The sector is a major extractor of fresh water, affecting global scarcity3; the list goes on.

Although building and construction efficiency—both in terms of operational costs and embodied carbon (i.e. materials)—is improving, it has been projected that required building floor area will close to double globally from 2020 to 20504 and that ‘three-quarters of the infrastructure that will exist in 2050 has yet to be built’5. Regardless of improvements in efficiency and society’s ability to change these trends, it is clear that the construction sector has a dominant role to play in both mitigating global climate disaster and, more subtly, acclimatising society to the ‘new normal’ resulting from climate change. Shifting the reliance of the construction sector away from resource and energy intensive materials, such as concrete and steel, and toward lower-carbon earth- and bioresource-based materials is one component—albeit a critical component—required for reducing the overall impact of the construction sector6.

This paper focuses on a single piece of this puzzle: large-scale adoption of bamboo as a construction material (Table 1). It must be emphasised that bamboo as a construction material is but one ‘tool’ in the engineers’ or builders’ toolbox for reducing the impact of the construction sector. The potential for penetration of bamboo into the construction sector will be a function of the bamboo resource available and available competing construction materials. It is unlikely, for instance, that bamboo will see adoption in a market such as North America where bamboo is not endemic and sustainable softwood is abundant. At the other extreme, many island nations have vast potentially untapped bamboo resources which will compete favourably with other—typically imported—construction materials.

Bamboo

Bamboo, both in its full-culm (pole) form (Table 1a) and as a constituent material in a variety of engineered bamboo composite (EBC) materials (Table 1c; glue-laminated bamboo, cross-laminated bamboo, bamboo scrimber, etc.) is receiving considerable and growing recognition as a sustainable structural load-bearing construction material. As a construction material, bamboo holds remarkable potential for its fast growth and short harvest cycle (typically 3–5 years) resulting in considerable carbon sequestration ability, and its high strength-to-weight ratio. As a ‘woody’ lignocellulosic material, bamboo, the material composition of bamboo is similar to that of softwood timber7. Deterioration mechanisms8 (biological attack, UV, etc.) and pyrolysis behaviour of bamboo9,10 is similar to those of wood, albeit effected by the thin wall hollow geometry. Bamboo, however, has a unique morphology—it is essentially a unidirectional fibre-reinforced material—with very pronounced anisotropy11.

The word ‘bamboo’ is about as descriptive as ‘wood’. Only about 7% of the approximately 1400 species of bamboo are believed suitable—in terms of geometric and material characteristics—for construction use in their full culm form. Today, perhaps only about a dozen species are used commercially in full-culm construction. Interspecies and intraspecies variation of bamboo is significant and bamboo resources (plantations, natural forests, etc.) must be characterised individually. Due to inefficiencies in transporting bamboo over long-distances, to be ‘sustainable’, bamboo must be used as a local or regional resource12,13. Nonetheless, in some instances imported bamboo can have a lower impact than conventional construction materials, especially when the latter is also imported14. Although the focus of this paper is the use of bamboo in its full-culm or minimally processed form, much of the discussion is equally relevant to engineered bamboo15. Full-culm bamboo, after all, is the ‘raw material’ or ‘feedstock’ for all engineered bamboo products.

Enabling the construction sector

Building Codes and Standards and Material Specifications (collectively referred to as Standards) are the lingua franca of the construction sector. Standards are essential for public health, safety and welfare, and also serve technical, social and economic objectives16. The adoption of so-called ‘non-conventional’ or unfamiliar materials—such as bamboo—in the construction sector is often throttled by regulation and industry [mis]trust. Standards provide a basis for trust between project stakeholders, including owners, designers, occupants, regulators, and ultimately the public at large by enabling stakeholders to effectively communicate within a common framework17.

Design standards’ development in the realm of bamboo materials is further complicated by the less homogenous stakeholder communities and users with diverse experience18. What we refer to as ‘engineering design’, is often not completed by an ‘engineer’ and is much less formal in the housing sector, especially in the Global South. To be effective, standards for such materials need to be context-appropriate16. Standardisation leads to broader acceptance of a material or system in the design community which, coupled with advocacy, can lead to broader social acceptance of previously marginalised or unfamiliar construction materials and methods19.

Structural design with full-culm bamboo is enabled by a suite of ISO standards addressing materials characterisation20, grading21 and structural design22. A similar suite of enabling standards is being developed for engineered bamboo products23,24,25 whereas characterisation of the bamboo feedstock used for engineered bamboo may also follow ISO characterisation20 and grading21 standards. The ISO design standard for full-culm bamboo22 leverages established timber design and has provision for both ‘design by testing’ and ‘design by tradition’. The latter approaches specifically allow marginally engineered systems and reflect the reality of informal engineering in the Global South16.

Standard material or material standard?

For conventional construction materials, engineered materials specifications (or standards) result in standard (or standardised) materials and building products. However, for bioresource- and earth-based materials, the development of standard materials is challenged by high material variability and often the reliance on local or traditional construction methods.

Whereas conventional engineered materials develop through the ‘formulation and synthesis of new compounds with structural control primarily at the micrometre scale’26, the properties of bioresource-based materials result from the complex architecture of the material over a variety of scales26. Bioresource-based materials have evolved (or formed) to a ‘local optimum for a given set of requirements and restraints’, these include both mechanical and biological functions26 and are usually different from the engineering uses to which the materials are applied. For example, bamboo has not evolved to accept penetrations for bolting pieces together whereas steel has been engineered to be bolted (or, indeed, welded).

The natural variation inherent in bioresource-based materials affects both the construction process and the building performance.

The challenge of material variation can be addressed by various strategies. For instance, wood exhibits large variability, yet we develop both prescriptive and performance standards for timber construction27,28. While the number of wood species is great, the primary strategy used in timber standardisation is to group species according to their structural properties, prescribing uniform grade-determining data for each group—the differentiation between softwood and hardwood is the simplest such grouping. Using this approach, material properties can be specified across a range of species29 while the processing of wood into sawn or engineered timber addresses geometric variation. This approach is essentially specifying a material standard in an arena where we cannot reasonably specify a standard material. Timber construction, however, has the benefit of centuries of reliable engineering data upon which to establish confidence; bamboo does not.

Bamboo material properties for construction

Substantial literature reporting the mechanical characterisation of bamboo has been produced in the last few decades. Such studies have expanded knowledge of tropical, sub-tropical and temperate species30,31,32. Due to its dominance in the Chinese domestic (close to 100%33) and global (approximately 50%34) markets, the majority of characterisation data is available for Chinese Phyllostachys edulis (commonly called Moso bamboo). Comparable data for Moso transplanted to other regions is available35,36 and highlights intraspecies variation.

Nonetheless, there is a recognised need for establishing a consistent and comprehensive worldwide database of bamboo geometric, physical, and mechanical properties37,38. There are relatively few studies assembling interspecies data from multiple sources39 and these often report significantly varying results. A new RILEM-led initiative38 is aimed at establishing such a database although data integrity and consistency across multiple sources is proving a challenge.

Safe structural design requires reliable material standards or specifications. For timber and bamboo, characteristic strength properties used for design are conventionally 5th percentile values reported with 75% confidence22,28,29. Assuming a large sample size, the ‘design strength’ is therefore about 1.7 times the standard deviation less than the experimentally determined mean40. When variation is high—coefficient of variation in bamboo test results on the order of 20–30% is common—the material efficiency (ratio of allowable design strength to actual material strength) is poor. Once additional design standard-prescribed22 exposure, structural use and safety factors are applied, it is rare that the designed-for stress in a full-culm bamboo structure will exceed 20% of the bamboo material strength. This structural inefficiency affects both the monetary and environmental costs of building with bamboo and implies to designers that the material is inherently unreliable, making it difficult to advocate for. Furthermore, due to its variability and the need to verify compliance with standards, bamboo requires materials test protocols that, while suitably easy to perform in the field41, are limited in terms of their accuracy. To maintain the desired (or standard-prescribed) confidence, a greater frequency of field testing is required than for engineered materials.

In this paper, the discussion is focussed on the mechanical behaviour of bamboo. Other important engineering properties of construction materials include durability (as it relates to long-term building performance) and fire resistance. The approaches described in the following sections are equally appropriate applied to these material characteristics as they are to the mechanical characteristics described.

Material informatics

Discovery (or ‘development’, if the reader prefers) of modern engineering materials tends to be aimed at describing and optimising the ‘process-structure-property’ relationship of the material, usually using physics-based methods42,43 ultimately founded in experimental research. The proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) or machine learning (ML) approaches to materials discovery44,45 decompose the process-structure-property relationship into process-structure and structure-property functions.

Material informatics (MI) ‘survey[s] complex multiscale information in a high-throughput, statistically robust, and yet physically meaningful manner’46. In doing so, MI overcomes barriers between materials discovery by materials scientists and materials selection by engineers, manufacturers and consumers47. MI can ‘engage materials research in the overall design approach of prototyping and commercialisation’47—or in the case of construction, standardisation.

MI requires robust datasets capturing process-structure-property relationships. For bamboo, the structure-property relationship is more critical; process being natural and ultimately less controllable, predictable or consistent. Nonetheless, large and reliable databases are required which simply do not exist. Complicating this, material structure data exists over a range of length scales obtained using increasingly complex methods. For bamboo, culm geometry is easily obtained using a tape measure, and basic culm section morphology (e.g., variation of geometry, fibre bundle distribution, etc.) can be obtained using digital imaging and relatively low power microscopy (ubiquitous in literature). Vascular and cell structure microstructure is obtained from scanning electron microscopy (SEM)48,49,50 and finer scales can be obtained using atomic force microscopy (AFM)51. Three-dimensional microstructure requires more complex techniques such as x-ray computed tomography (CT)49,50. For an MI approach to establishing bamboo structure-property relationships to be sufficiently robust and yet accessible to practitioners using bamboo, data must be concentrated at scales at which it is readily obtained: the macroscopic level. An approach to MI for bamboo that overcomes the potential socioeconomic inequity or bias in data acquisition is needed.

Bamboo informatics

For use in construction, we are mostly interested in cross-section and culm-scale properties. The inherent variation of bamboo structure also primarily occurs at this macroscopic level. Gross-section material properties are of interest and many researchers conclude that the bamboo fibre volume ratio, and its distribution in the culm provides a reasonable surrogate for longitudinal mechanical properties of the bamboo culm: bamboo is a functionally-graded long-fibre-reinforced material11,52,53,54,55. As a result, mechanical properties in the longitudinal direction of the culm are reasonably captured by the well-known ‘rule of mixtures’ approach for fibre-reinforced composites11,50,51,52,53,54,55; although this analogy has been shown to break down when transverse mechanical properties are considered11.

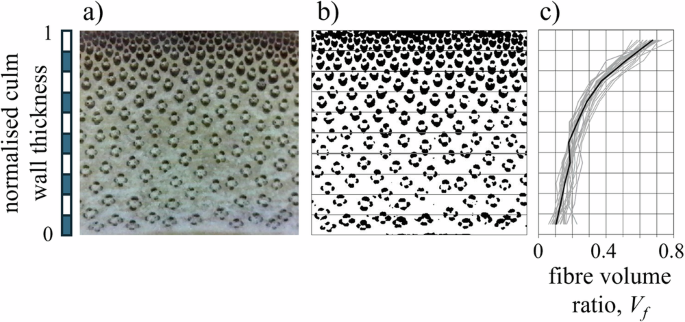

Assuming the rule of mixtures provides an appropriate structure-[longitudinal] property relationship allows simple digital imaging (using a mobile phone camera or tabletop scanner, for instance) and simple image processing software to establish the fundamental structure-defining properties: gross geometry (diameter, culm wall thickness) and fibre volume ratio56. Such a simple informatics approach is demonstrated in Fig. 1 and is easily adapted for in-the-field use. A similar approach was used to characterise over 3000 individual culm wall sections used in glued-laminated bamboo beams57—offering a means of not only rapid data acquisition but also quality assessment of the engineered bamboo product.

a A 640 × 480 image of 10 mm thick P. edulis culm wall obtained using digital camera resulting in resolution on the order of 40 pixel/mm. b MatLab-derived pixel map of fibre distribution divided into ten layers through the culm wall thickness. c Resulting fibre volume distributions for 28 samples. The black line in c corresponds to images (a) and (b).

Although image acquisition can be done in the field using a mobile phone camera, this does not realise the database required to generate, curate, store and maintain this information in a form that can be used in MI models. Structure must be correlated with material properties and ultimately, structural performance.

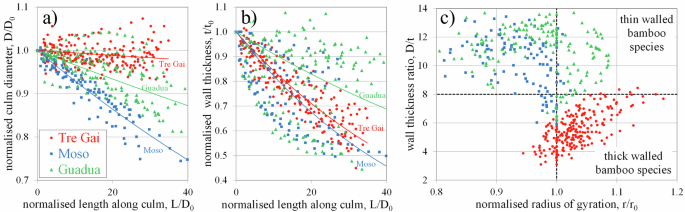

A pilot-study example of such knowledge discovery from bamboo material geometry data for predicting the buckling behaviour of bamboo culms is reported by Harries et al.58. In this study, a dataset of bamboo culm diameter, D, and wall thickness, t, distributions along the culm length, L, was established for samples of three bamboo species illustrating that, as expected, both geometric properties taper with height and the taper varies with species (Fig. 2a, b). Buckling behaviour, however, is affected by the radius of gyration, r, of a cross-section. This derived geometric property (radius of gyration is equal to the square root of the ratio of the moment of inertia to the area of the cross-section; i.e., r = (I/A)0.5) was found to have two distinct characteristics and a relatively clear threshold between these (Fig. 2c): for culms having thin walls (D/t > 8), r decreased with height along the culm, however for thicker wall species (D/t < 8), r increased with height. This finding has implications for the design of full-culm bamboo columns but also suggests a potential classification of bamboo species (at least as they relate to axial-load-bearing elements): thick- and thin-walled bamboo58. While this example is simple and largely confirms what may be considered common sense—that thicker-walled species are more appropriate for column elements—it nonetheless, places this observation firmly in the realm of fundamental mechanics and has implications for structural design.

a Culm diameter D (normalised by diameter at culm base, D0) variation over culm length (normalised by D0). b Culm wall thickness t (normalised by wall thickness at culm base, t0) variation over culm length (normalised by D0). c Proposed classification of species by radius of gyration r (normalised by radius of gyration at culm base, r0).

In order to effectively realise bamboo informatics at a meaningful scale, bamboo stakeholder communities must adopt a global citizen scientist (https://www.citizenscience.gov/#) approach coupled with dedicated curation to realise a thorough and robust database. A nascent RILEM committee focusing on the materials characterisation of bamboo has this realisation of bamboo informatics as an objective38.

Full-culm bamboo as feedstock for engineered bamboo composite products

Engineered bamboo composites (EBC) are assemblies of bamboo strips (laminated or cross-laminated bamboo), splits (flattened bamboo) or fibre bundles (scrimber) bonded using a resin59. EBCs are dimensionally stable and fabricated to be an alternative material consistent with laminated and sawn timber materials (Table 1c). Indeed, design with EBCs is essentially the same as that for timber design27,28. Material utilisation, however, is poor and is inversely proportional to the engineering quality of the product, varying from as high as about 60% harvested material mass in the final product (bamboo plywood) to as low as 20% (laminated bamboo)60. Offcut or waste bamboo is typically burnt as fuel—releasing sequestered carbon. In EBCs, ‘glue’ or resin content is typically high (as high as 25% in some scrimber products59) and glueline performance limits structural performance61. That is, an EBC, limited by glueline performance, is less structurally efficient than it might be if the bamboo strength could be fully utilised. Improved models of the structure-performance relationships of bamboo will also improve the structural efficiency and utilisation of bamboo in the EBC industry.

In particular, performance relationships that describe wettability (associated with the efficacy and performance of the gluing process) of bamboo are required to improve EBC performance and material efficiency and utilisation. Described simply, when bonding adjacent bamboo strips, there are three possible interface conditions: inner culm wall-to-inner culm wall (I-I), outer-to-outer (O-O) and inner-to-outer (I-O). Due to differences in hydrophobicity of the inner and outer strip surfaces, wettability (of the resin) is different affecting bond capacity and EBC performance. Little work has been done in this area60,62,63,64 and some reports seemingly contradictory results65.

Marginally engineered bamboo

In full culm bamboo construction, regardless of material properties, bamboo must be relatively straight and prismatic (i.e., have little cross-section change along its length)22. In its full-culm form, bamboo will always be limited by its natural variation and many species will never be suitable for full culm construction. While rigorous grading protocols21 may select for appropriately straight and uniform culms, this comes at the cost of greater waste (i.e., rejected culms). A second challenge of full-culm bamboo construction is designing round member-to-round member connections for; these are either limited in capacity or exceptionally complex to construct making them poorly suited to broad implementation66. EBCs overcome some of these limitations of the bamboo resource but can be economically and environmentally costly.

Engineering on a spectrum (Table 1b), marginally engineered bamboo (MEB; sometimes referred to as lightly-engineered bamboo) aims at producing floor and wall assemblages from bamboo resources that needn’t be straight and prismatic with minimal machining and simple fabrication67,68,69. MEB, as currently envisioned, fabricates sandwich panel structures by partially squaring the round culms to allow simple and efficient adhesive connections. In many instances, the resulting offcuts can be used to fabricate the sandwich panel veneer or other woven bamboo panel elements69.

Bahareque (also referred to as light cement bamboo frame22) construction70,71—involving rendered walls placed over a bamboo frame and lath structure—is another construction technique utilising minimally processed bamboo. Like timber frame construction, bahareque construction encloses the bamboo allowing a greater amount of marginal bamboo resource—perhaps that deemed aesthetically unacceptable—to be used.

Changing the design paradigm

Unique approaches to achieving near 100% utilisation of a timber resource have been demonstrated wherein each rough-cut piece is scanned and design is carried out using a process of form finding and optimisation using the defined resource72. Similar approaches have been proposed for bamboo73,74. Such approaches are data intensive, require minute characterisation of each culm (typically through a process of three-dimensional scanning) and address only geometry. Structural performance is a function of geometry and material properties; for these so-called ‘performative design’ approaches to be successful, once again, reliable structure-performance relationships are required.

Digital fabrication techniques—essentially three-dimensional machining—have also been proposed75 and hold considerable promise for designing unique culm-to-culm connections. Similar to performative design, digital fabrication affects only geometry while relying upon known material performance. It is yet to be determined whether such performative techniques can be translated and scaled to a point at which they may contribute meaningfully to addressing the global housing crisis.

Conclusion: moving full-culm bamboo construction from nonconventional to non-negotiable

At present, the construction industry refers to bamboo as a ‘nonconventional’ construction material. The opportunities for bamboo as an alternative material that can contribute substantially to reducing the global carbon footprint of the construction sector must be realised6. Appropriate and efficient adoption of a new construction material, as described in this paper, has a number of moving parts. Context-appropriate building standards are required. These, however, must be enabled by material standards. With the exception of perhaps a handful of geographically-specific bamboo resources, there remains a dearth of reliable materials information for bamboo. Applying a bamboo informatics approach can consolidate this gap by integrating materials research into the needs of design and standardisation47. The manner in which bamboo informatics is undertaken and ultimately integrated into design and materials standards must be globally accessible in order to overcome socioeconomic and technical inequity. The informatics approach is appropriate across the spectrum of bamboo construction shown in Table 1.

Nonetheless, the use of full-culm bamboo will always be limited by its inherent variability. Aggregating culm properties in marginally engineered bamboo (MEB) assemblages or in engineered bamboo composite (EBC) members and structures serves to mitigate the effects of individual culm variation. Additional engineering however comes with additional complexity and cost (Table 1). The ‘less precise’ nature of MEB is not as sensitive to the limitations imposed by fabrication methods of EBCs. MEB, while less familiar to the construction industry represents the greatest potential impact when considering housing needs of the Global South (Table 1). MEP can be optimised to minimise waste and offcuts, and can be assembled at minimal cost in less formal environments. Indeed, it is envisioned that MEP, like full culm bamboo, can be constructed locally by local workers in many instances69.

This paper has attempted to provide a technical perspective for ‘normalising’ bamboo as a construction material, moving bamboo from the realm of so-called ‘non-conventional’ material to ‘just another tool in architects’ and engineers’ toolboxes’. In this paper, I have not addressed the social or cultural contexts for this necessary shift. Bamboo is often referred to as ‘being for poor people’ and is rarely preferred over ‘conventional’ materials which are thought to project wealth and progress. This paradigm must be overcome and is the subject of an entirely different field(s) of study. Nonetheless, technical acceptance, as illustrated by the development of standards and the priority application of cutting-edge informatics methods, coupled with advocacy, can enhance confidence and cultural acceptance, ultimately shifting bamboo construction materials from non-conventional to being non-negotiable.

Responses