Advances in antimicrobial techniques to reduce postharvest loss of fresh fruit by microbial reduction

Preservation techniques

Physical method

Recently, research into improving non-thermal process to lessen microbial counts on fruits has gained interest as thermal processes deteriorate the physiological, biochemical, and physical properties of fruit18,19. In recent decades, conventional thermal processing has been substituted by numerous non-thermal processes like low temperature, UV-light, pulse light, ionizing radiation, high pressure, cold plasma, and ultrasound. Table 1 shows the different physical methods for the preservation of fruits.

Low temperature

Low-temperature preservation techniques for fruit preservation have been a commonly adopted method20. The use of temperatures range of 0–10 °C for refrigeration and <–20 °C for freezing storage of fruits increases the availability and supply area throughout the year. Consumers prefer refrigerated fruits more than frozen fruits due to their better freshness and lower chilling injury (CI) than refrigerated fruits. However, refrigerated fruits have a shorter shelf life compared to frozen fruits21. In addition, detecting chilling injury (CI) in most fruits during cold storage poses a challenge, as CI symptoms manifest only upon returning the fruits to room temperature. The critical temperature for CI and its visible symptoms vary significantly across different fruits. Subtropical and tropical fruits exhibit CI temperatures ranging from 0 to 13 °C22. Common symptoms of CI in horticultural products include surface water stains (e.g., cucumber and kiwifruit), surface depression and browning (e.g., banana, orange), woolly texture (e.g., peach and nectarine), loss of maturity (e.g., tomato and guava), and seed and calyx browning (e.g., sweet pepper)23. Additionally, the maturity of fruits at harvest significantly influences CI occurrence. Studies indicate that CI severity decreases with increasing fruit maturity. For instance, mango fruits harvested during the green-ripened period exhibit higher CI compared to those harvested during the yellow-ripened period at 2 °C24. Horticultural products respond differently to low temperatures, roughly categorized into three groups: A) chilling resistant, B) chilling sensitive, and C) slightly chilling sensitive. Type A products resist chilling and do not experience CI. Thus, higher temperatures allow for longer storage times above freezing. Type B and C products are chilling sensitive and develop CI below the critical chilling temperature. Consequently, below this storing at temperatures below this threshold extends storage duration. CI occurs when temperatures are above freezing but below the critical chilling threshold, diminishing product storage longevity23. Hence, recognizing an ideal cooling temperature is critical for efficient fruit preservation. In addition, low temperatures reduce the respiration rate and progression of pathogenic microbes. However, the shelf life at low temperatures varies with fruit types and variety. For example, Kim et al. stored three kiwifruit varieties at 22 and 2 °C, and found that refrigerated kiwifruit showed delayed ripening and increased shelf life by 7-10 weeks25. They also found that Cheonsan kiwifruit had a shorter shelf life than ‘Daebo’ and ‘Daeseong’ kiwifruit varieties at 22 and 2 °C. Zhao et al. reported an extension of the storage period of sweet cherry fruit up to 100 days when stored at near-freezing temperatures26. However, low-temperature treatment is not applicable in the same manner for all types of fruits. Some fruits, such as apples, cherries, grapes, peaches, pears, and nectarines, show chilling or freezing injuries. Also, there is a high cost of maintaining low temperatures during storage time.

Ultraviolet light

Ultraviolet (UV) light is electromagnetic radiation 100–400 nm wavelength that can be categorized into UV-A, UV-B, UV-C, and vacuum-UV with the wavelength range from 315–400 nm, 280–315 nm, 200–280 nm, and 100–200 nm, respectively27. UV light has a broad-spectrum bactericidal effect that is economical, user- and eco-friendly28. Ultraviolet light is absorbed by bacteria DNA, forming thymine dimers, and interrupting DNA replication which causes genetic mutation and bacterial inactivation (Fig. 3)29. UV light treatment has been extensively used for surface disinfection of fruits. Apples treated with UV light exhibited lower weight loss and browning throughout storage30. The bactericidal effect of UV light depends on the wavelength and light dose, fruit types, and types of bacteria28. Generally, a higher lethal ability of UV light is reached at 254 nm (wavelengths near the absorption peak of DNA) or higher applied doses and fruits with a smooth surface28. For example, when apples, pears, and strawberries were inoculated with Escherichia coli and treated with UV-C light at 0.92 kJ/m2, the microorganisms were reduced by ~3, ~2, and ~1 log CFU/g, respectively. A higher reduction of microbes in apples was observed because of the smoother surface of apples than pears and strawberries31. Sometimes, the application of UV irradiation treatment has often been linked with concerns regarding potential loss of nutritional value and sensory quality32. Nevertheless, research indicates that exposing fruits to UV irradiation prior to storage effectively reduces the development of postharvest diseases33. For instance, Castagna et al. demonstrated that UV-B treatment of two tomato varieties led to increased concentrations of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and flavonols in the peel and flesh34. UV-C irradiation triggers various biological processes and elevates respiratory rates. Erkan et al. observed an increase in the respiration rates of squash following UV treatment, which correlated with higher UV-C intensity35. Conversely, Vicente et al. found that UV-C treated peppers exhibited lower respiration rates compared to untreated control fruits36. Hence, the impact of UV treatment on fruit quality necessitates a case-by-case evaluation, considering multiple influencing factors36. The main drawback of UV light usage is its lower penetration power and long exposure time, which affects fruit quality28. In addition, prolonged exposure to UV light can alter some UV light-sensitive compounds (vitamins, amino acids, and fatty acids)37.

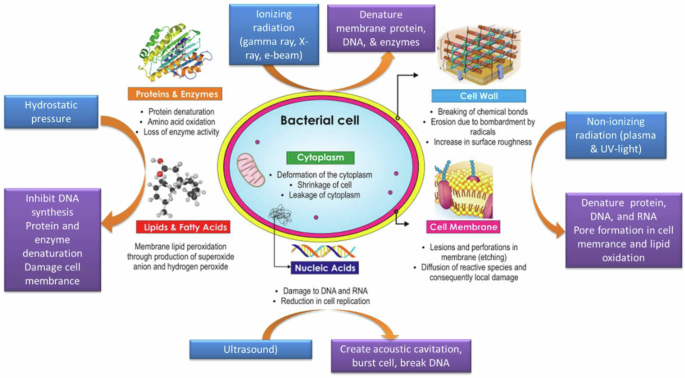

Ionizing radiation such as gamma-ray, electron beam, and X-ray cause damage to the cell membrane, denature DNA by thymine dimer formation, and inactivate enzymes; non-ionizing radiation such as UV-light and plasma produce highly reactive gaseous molecules and ions that arrest DNA replication, induce pore formation in the cell membrane, denaturing membrane and cytoplasmic proteins, and oxidize lipids; hydrostatic pressure damage cell membrane and inhibit DNA synthesis; ultrasound creates acoustic cavitation and form bubbles in the cytoplasm resulting in DNA breakage and bursting of cells (Adapted from Misra and Jo)73. (Figure created using Microsoft PowerPoint).

Pulsed light

Pulsed light (PL) is an enhanced form of UV-ray technique with a wavelength of 200–1100 nm, produced by the inert-gas lamp38. The PL applied for fruit surface disinfection is generally pulsed at 1 to 20 flashes/sec with an energy density of 0.01 to 50 J/cm239. The bactericidal effect of PL is 4–6 times higher than continuous UV light40. The mode of bacterial inactivation of PL is similar to UV-light, but PL also causes photothermal and photophysical effects for microbial inactivation41. A study by Bialka and Demirci showed that treatment in raspberries by 59–72 J/cm2 PL decreased the E. coli and Salmonella count by ~4 and ~3,5 log CFU/g, respectively42. The bactericidal effect of PL depends on the pulse, types of bacteria, and fruits. Generally, higher pulse fluence has a higher bactericidal effect. For example, a reduction of E. coli populations from 2 to 4 log CFU/g on blueberry calyx was observed when the fluence of PL treatment increased from 5 to 56 J/cm243. Also, Gram-negative bacteria and bacterial vegetative cells are more sensitive to PL than Gram-positive bacteria and bacterial spores44. For example, the reductions of ~3 log CFU/g of E. coli and ~4 log CFU/g of Salmonella on strawberries were observed when treated by PL in the same condition42. Pulse light is considered a non-thermal technology if used for short periods or low fluence. However, a longer treatment time considerably increases the temperature of the treated sample, which results in the deterioration of product quality43. Severe discoloration, high temperature, and burnt appearance on the surface of blueberries were observed when treated with PL for 60 sec43. In another study, Aguilo-Aguayo et al. observed softening, wrinkles, and increased weight loss during storage when tomatoes were treated with PL45. Also, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) approved the PL application on food with the highest fluence of 12 J/cm246. However, a high level of PLA is required disinfect the fruits. Therefore, to attain the industrial-scale application of PL for fruit disinfection, further research is required to improve the operational environments and use chilling methods to lessen the increasing temperatures.

Ionizing radiation

Ionizing irradiation is used for decontaminating fruits and is approved by the US FDA because it is environmentally friendly47. Only gamma rays (γ-ray), electrons-beam (e-beam), and X-ray radiations are acceptable in foods48. Ionizing irradiations inhibit or kill microorganisms by various means, such as breaking DNA strands and denaturing membrane proteins and enzymes (Fig. 3)49. Also, ionizing irradiations generate free radicals in microorganisms by ionizing the water molecules50. The efficiency of ionizing irradiation on microorganisms depends on the irradiation source, dose, dose rate, and types of microorganisms and fruits. The γ-ray exhibited higher penetration capability and energy effectiveness than e-beam or X-ray51. However, the source of γ-ray radiation cannot be turned off instantly. On the other hand, e-beams and X-rays can be turned off or turned on according to the requirements, which offers a commercial advantage to e-beams and X-rays over γ-ray51. The sterilization efficacy of irradiation is enhanced when applied at a higher intensity and dose. Although the FDA approved the irradiation of some food up to a certain intensity, the routine consumption of irradiated fruits is a concern to human health risks52. Also, ionizing irradiation setup involves high maintenance costs and initial investment53.

High hydrostatic pressure

In high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) treatment, fruits are treated with water at a high pressure (100–800 MPa)54. HHP is one of the sterilization techniques with negligible adverse effects on a fruit’s nutritional and sensorial properties55. HHP mainly inactivates bacteria and molds by damaging the cell membrane, denaturing enzymes and proteins, and inhibiting DNA synthesis (Fig. 3)56. In addition, the high pressure of HHP causes the detachment of membrane proteins, ultimately modifying the cell permeability and functionality, resulting in cell death11. The antimicrobial activity of HHP varies with pressure level, temperature, treatment duration, types of microorganisms, and fruit species. Generally, microbial counts are inversely proportional to the processing pressure, duration, and temperature. Also, Gram-positive bacteria and mold spores exhibited more resistance to HHP than Gram-negative and mold mycelia, respectively55. Although HHP has excellent antimicrobial efficacy, a substantial change in the texture and color of a few treated fruits was noticed after HHP treatment57. Also, HHP-treated fruits must be kept and transported in refrigerated conditions. Hence, HHP treatment methods must be optimized carefully to enhance the shelf life and maintain the quality of fruits.

Low pressure

The low-pressure storage method, also referred to as the decompression method of fruit storage, was pioneered by Burg and Burg in 1966. It involves storing horticultural products under sub-atmospheric pressure conditions, typically around 50 kPa58. Since its inception, numerous studies have been conducted to enhance the quality and preservation of various fruits such as strawberries, pears, tomatoes, and mangoes59,60,61,62. Hypobaric treatment enhances the natural defense mechanisms of fruits against external pressure and microbial attacks, slows down their metabolic activities, and extends shelf life. For example, hypobaric treatment has been shown to maintain the firmness and color values of apple fruit while reducing microbial decay when stored at 20 ± 3 °C63. Studies by Huan et al. demonstrated that hypobaric treatment of kiwi fruit decreased alcoholic flavor, fruit decay, and weight loss during storage, thereby extending shelf life64. Moreover, maintaining fruits under hypobaric conditions (25 kPa) for 30 minutes, once or twice, preserved quality parameters such as total phenolics, quinic acid, and citric acid in sweet cherries, grapes, strawberries, and apples. In strawberries, six hours of hypobaric treatment proved more effective against fungal decay than four hours of hypobaric treatment65. Combining hypobaric pressure (50 kPa) with 1-MCP treatment on apple fruit for 4 hours, followed by cold storage, retained quality parameters during a 120-day storage period63. In mangoes, delaying ripening by maintaining fruit at 13 kPa extended shelf life62. Hypobaric treatments have also demonstrated efficacy in inhibiting or reducing losses and spoilage due to fungal infections in grapes, cherries, and strawberries, suggesting their potential to induce resistance against pathogen66. Storage under low oxygen partial pressure slows fruit metabolism, leading to reduced ethylene production. Additionally, air renewal facilitates ethylene elimination, delaying ripening processes and prolonging postharvest life67. Despite its benefits, the widespread adoption of hypobaric storage technology in the industry may be limited by investment costs and a lack of awareness regarding its advantages68 (Box 1).

Cold plasma

Cold plasma (CP) is a non-equilibrium plasma that inactivates microorganisms on the fruit surface without significantly increasing the treated fruit’s temperature69. Beside microbial inactivation, CP has been also used in inactivating enzymes and degrading pesticides70. Corona discharge, microwaves, or dielectric barrier discharges at atmospheric or low pressure produce cold plasma71. The antimicrobial potential of cold plasma is mainly due to highly reactive gaseous molecules and ions that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and UV-photons in the microorganism72. The ROS and RNS cause membrane and DNA damage, which can cause cell leakage, cell replication, and cell death (Fig. 3)51. In the last two decades, cold plasma treatment has been used for the in-package decontamination of fruits. Cold plasma at atmospheric pressure using air has been more widely used for fruit disinfection than other cold plasma sources because of the high equipment cost and short life of charged helium and argon ions73. It is reported that packaged strawberries treated with dielectric barrier discharged atmospheric cold plasma for about 5 min reducing total mesophiles, yeasts, and molds by 2–3 log CFU/g74. Also, cold plasma treatment does not significantly affect a treated fruit’s physical and biological properties70. The antimicrobial effectiveness of cold plasma depends on the plasma source, types of gas used, treatment time, types of microorganisms, and fruit species75. Generally, microorganisms can be inactivated easily from fruits with smooth surfaces compared to those with rough or complex surfaces70. Ziuzina et al. exhibited that cold plasma treatment on cherry tomatoes for 10, 60, and 120 seconds reduced the Salmonella enterica Typhimurium, Listeria monocytogenes, and E. coli to levels below detection from the initial inoculated population of 3.1, 6.7, and 6.3 log CFU/sample, respectively76. In contrast, strawberries took around 5 min of treatment to have the same results. Applying high voltage in cold plasma treatment results in arcing between the electrodes, which can result in burn damage to fruit surfaces77. Therefore, more research is needed on the effect of operational parameters of cold plasma on food components for industrial-scale applications.

High-intensity ultrasound

High intensity ultrasound (HIUS) has a frequency range of 20–100 kHz and is considere d a non-thermal antimicrobial process78. High intensity ultrasound treatment is non-toxic, safe, highly efficient, and eco-friendly79. High intensity ultrasound is generated by the transmission of ultrasonic waves through a liquid, producing acoustic cavitation, which results in the formation of micrometer-sized vapor-filled bubbles78. High intensity ultrasound has been applied in surface cleaning, homogenization, emulsification, and inactivation of microorganisms80. High-intensity ultrasound has recently been used to preserve fresh fruits such as kiwifruit, plum, litchi, and strawberries by reducing the microbial count81,82,83. High intensity ultrasound treatment stimulates secondary metabolite accumulation and enhances antioxidant activity in fruits84. High-intensity ultrasound should be combined with other chemicals, such as essential oils, chlorine dioxide, and sodium hypochlorite to get a higher antimicrobial activity85,86,87.

Pulsed electric field (PEF)

Pulsed electric field (PEF) is a powerful non-thermal technology with great potential to maintain quality attributes and extend the shelf life of fresh fruits88. In this technique, high voltage electric pulses are applied for a short time (microseconds), resulting in electro-permeabilization of the content of the cellular membrane, leading to the transfer of intracellular components and thus inactive microorganisms, without significant effects on the other food constituents89. However, this innovative technology has some limitations, such as unavoidable chemical reactions leading to electrode fouling and corrosion, migration of electrode elements, and chemical modifications of fruit constituents. Therefore, these limitations may influence consumer acceptability, regulatory aspects, commercialization, and wide applications of this technology in food processing90. Despite such limitations, PEF has been applied as a postharvest processing method for various fruits and has been found to improve storage stability without significant influence on the product’s physicochemical, nutritional, and sensorial quality attributes89. In 2005, PEF-processed organic fruit juice products were sold in the commercial market in Oregon, United States. In recent years, PEF technology has been used for extraction and dehydration of foods where lower field strength (<10 kV/cm) is employed91.

Hot water treatment (HWT)

Hot-water treatment (HWT) is a desirable fruit preservation method because of several advantages over usual chemical treatments. Research indicates that washing fruits with hot water at temperatures of 60 or 40 °C proves more effective compared to chemical treatments. This effectiveness is attributed to the superior ability of thermal treatments to penetrate deeper into the fruit, unlike chemical treatments that are limited to surface contact92. Thermal treatment can elevate the temperature of both the fruit surface and the underlying parenchymal tissue through heat transfer. Moreover, while both physical and chemical treatments aim to remove spores from the fruit epidermis, thermal treatments offer two distinct advantages. Firstly, they alter the structure of waxes in the cuticle, enabling them to fill micro-cracks or wounds93. This was evidenced by scanning electron micrographs of cherry tomato fruit epidermis, which revealed cracks filled with molten wax after immersion in hot water at 40–45 °C. Secondly, hot water treatment (HWT) effectively destroys fungal mycelia and spores present on the fruit surface94. HWT is highly reproducible, efficient, relatively inexpensive, chemical-free, fast to perform, and suitable to apply on an industrial scale95. Hot-water treatment induces several physicochemical changes in the fruit and has been applied to different fruits to reduce the decay caused by different pathogens96. Garcia et al. inoculated mandarin and oranges with Penicillium digitatum and Penicillium italicum followed by dipping them in hot water (45 and 53 °C) for 3 minutes before storage at 5 or 20 °C97. They found that HWT significantly reduced firmness and decay incidence in fruits after 5-day storage at 5 °C and 7 days of shelf life at 20 °C. Kabelitz and Hassenberg, reported that a HWT of apple at 55 °C for 30 sec to 2 min reduced the microflora and inoculated microbes on the apple’s surface by 2-3 logs95. The HWT is employed in commercial lines of pepper, melon, mango, and grapefruit in Israel, with a 3–4 t/h capacity98. The use of HWD for mango is widespread in the USA, Central America, and the Philippines99. In Europe, HWT is currently used to treat organic apples100. However, the technique may be commercially suitable for the postharvest treatment of other fruits, such as peaches and nectarines101. Also, combining HWT with other non-chemical techniques such as irradiation, plant extracts, biocontrol agents, and other physical methods should be examined.

Vapor heat treatment (VHT)

Vapor heat treatment (VHT) is a sterilization technique for fruits commonly practiced in industries. In VHT, the fruits are kept at 40–55 °C for a few minutes to several hours in air saturated with water vapor. In some cases, fruits are preconditioned to tolerate the VHT temperature102. In general, VHT is applied to disinfect the fruit from insect pests and fruit flies; however, there are some research available in the literature on the antimicrobial effect of VHT to increase the shelf life of treated fruits. Lydakis and Aked, treated table grapes with VHT in the temperature range of 52.5–58 °C for different time103. They found that the grapes treated at 52.5–55 °C for 18–24 min reduced the infection level of Botrytis cinerea by 72–95% after 9 days of storage.

Chemical method

Chlorine dioxide

Chlorine dioxide is a yellowish-green gas at room temperature. Chlorine dioxide gas can be produced in various ways, such as chlorate reduction using hydrogen peroxide, the reaction of sodium chlorite with chlorine or acid, and the electrolysis of sodium chlorite104. Chlorine dioxide has broad antimicrobial activity and higher oxidative activity than chlorine without forming carcinogenic by-products105. Chlorine dioxide destabilizes the cell membranes of microorganisms by altering the structure of proteins and lipids, subsequently enhancing membrane permeability and cell leakage that cause microbial cell death. Chlorine dioxide also induces oxidative stress and alters DNA replication in microorganisms106. The FDA approves the use of chlorine dioxide for fresh fruit sterilization47. Various reports are available on the use of chlorine dioxide to eliminate diverse microbes from fruits. Treatment of grapes with chlorine dioxide gas reduced the bacteria, yeast, and mold from the surface of the grape by 1–3 log CFU/g after 90 days of storage107. Also, chlorine dioxide application can maintain fruit quality. It is reported that the treatment of grapes with chlorine dioxide lessened rachis browning while they are being stored107. The effectiveness of chlorine dioxide depends on the form of chlorine dioxide (gas or liquid), the concentration of chlorine dioxide, treatment time, types of microorganisms, fruit type, and temperature. It is also reported that chlorine dioxide in the gaseous form has a higher sterilizing capacity than its aqueous form, which might result from the higher penetration ability of gas into microorganisms106. However, the aqueous form of chlorine dioxide is most common because of the ease of use with existing washing lines. Bridges et al. reported that the treatment of blueberries with gaseous chlorine dioxide (0.06–0.15 mg/g) for 2.5–5 h decreased Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, and Listeria monocytogenes by 1–4 log CFU/g108. Generally, the antimicrobial property of chlorine dioxide increased with increasing concentration, treatment time, and temperature109. Also, Gram-positive bacteria and spores were more resistant to chlorine dioxide than Gram-negative bacteria and vegetative cells106. In general, chlorine dioxide takes a long treatment time of 10–150 min to get the desired antimicrobial activity, limiting its application on an industrial scale53. Other limiting factors for chlorine dioxide application at an industrial scale are its high oxidizing capacity that results in color change in treated fruits, thermal instability at high temperatures and proneness to the explosion, and its potential to form toxic hydrogen chloride gas105.

Ozone

Ozone is a potent oxidative agent with wide-spectrum antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities110. Ozone gas is commonly produced by passing air or oxygen via a high-voltage electrical discharge system, which splits oxygen molecules into oxygen radicals that suddenly react with an oxygen molecule to generate ozone111. Ozone has high reactivity, antimicrobial efficiency, and oxidation potential with no residue in the treated fruits112. FDA has approved ozone applications for food disinfection, which are generally recognized as safe (GRAS)113. Ozone kills microbes by oxidizing cellular proteins and unsaturated lipids, creates free radicals and superoxides, breaks glycosidic bonds in cell walls (membrane disruption that allows ozone to penetrate the cells), and inactivates enzymes and nucleic acids114. Ozone has been reported to be widely used to deactivate microbes in berries, grapes, apples, peaches, etc112,115. Further, treating fruits with ozone does not significantly affect the nutritional quality. In addition, ozone is reported to eliminate mycotoxins and pesticide residues from fruits105,107. Hence, ozone application for disinfection offers a promising substitute for conventional chemical disinfectants. Agriopoulou et al. reported a 17-54% aflatoxin decrease by ozone application for 20 min at 8.5–40 ppm116. The antimicrobial efficiency of ozone varies with the ozone concentration, treatment time, and types of microorganisms and fruits112. The sanitizing proficiency of ozone in an aqueous form was found to be higher than in the gaseous state117. At the same time, the decay speed of ozone in an aqueous form is much more than in a gaseous state118. Generally, higher antimicrobial activity is achieved by a higher ozone concentration or exposure time. Bridges et al. reported a of 0.5 and ~1.5 log CFU/g reduction of Escherichia coli on blueberry and tomato, respectively, when treated with 300 ppm ozone for 5 h108. Also, Gram-positive bacteria are comparatively more sensitive to ozone than Gram-negative bacteria, vegetative cells are more sensitive than spores, and bacteria are more sensitive than yeasts and fungi119. Higher ozone concentrations or prolonged treatment times are required to obtain significant antimicrobial activity, which might trigger the oxidation of some ingredients in treated products, resulting in color, flavor, and phytochemical changes120. Chamnan et al. reported bleaching in longan fruit pericarp when treated with ozone121. Also, generating ozone and maintaining concentration is expensive and must be produced on-site53. Moreover, the capability of ozone generators needs further development to reach the requirement for industrial applications122.

High-pressure carbon dioxide

The microbial inactivation of food by high-pressure carbon dioxide (HPCD) has gained the attention of researchers in the last two decades. In HPCD technology, fruits are treated with either pressurized subcritical or supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2) for a specific time (5-30 min) at a temperature between 20–50 °C and pressure under 50 MPa123. Carbon dioxide is an easily accessible, non-toxic, and economical gas, which makes the HPCD technique eco-friendly and GRAS by the US-FDA for sterilizing fruits124. The microbial inactivation mechanism of HPCD is mainly because of the solubilization of CO2 in the outer medium, where it transforms the cell membrane of microbes and intensifies the membrane permeability, enters into the cell, and reacts with cytoplasm to decrease the cell pH, inhibiting enzymes and cellular metabolism123. Valverde et al. reported a reduction of 5 logs of S. cerevisiae when pears were treated with HPCD for 10 min at 10 MPa and 55°C125. The HPCD treatment can effectively damage the microbes without influencing the nutritional attributes of fruits. The efficiency of HPCD technology is considerably altered by changing temperature, pressure, exposure time, microbial types, and fruit species123. In HPCD technology, temperature and pressure are essential in destroying microbes. Pressure increases the solvation power and density of CO2, while temperature increases the cell membrane permeability and diffusivity of CO2126. HPCD treatment changes the quality of fruits by turning the medium acidic125. In addition, the costly equipment and process are the main hurdles in using HPCD for fruit treatment. Hence, more profound research on the influences of the HPCD treatment on microbial disinfection, fruit quality, and shelf life is required.

Electrolyzed water (EW)

Electrolyzed water (EW) has a potent antimicrobial effect on various microorganisms. It increases the membrane permeability, creates pores in the cell wall, and modifies the metabolic rate by altering the production of adenosine triphosphate in bacteria, which results in cell death127,128. The presence of chlorine in HOCl, Cl2, and OCl in electrolyzed water contributes to microbial destruction129. In particular, the OCl ion initiates the disruption of the cell wall and membrane by undermining the outer membrane and impacting the key protein functionality of the plasma membrane. HOCl can infiltrate the cells, traumatizing other internal cell organelles and microbial cell walls by inactivating enzymes, impairing cellular metabolic processes, and causing DNA damage. In addition, EW caused a reduction in the levels of cellular metabolites such as glucose, amino acids, and ribose-5-phosphate, as well as the activity of phosphate acetyltransferase-acetate kinase. The above-mentioned drastic alterations disturbed the normal metabolic pathways of bacteria leading to enhanced fatty acid metabolism, diminished amino acid and nucleotide biosynthesis, varied osmotic regulation, reduced energy-associated metabolism, and suppressed cell proliferation130. In addition to active chlorine, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated in EW, which causes microorganisms to be sluggish131. The antibacterial activity of EW is catalyzed by the contribution of O3, H2O2, and OH, formed during electrolysis132. Recently, EW has been noticed as a good substitute for sodium hypochlorite disinfection owing to its safe nature, cost-effective and eco-friendly quality, and easy operational aspects133. EW demonstrates excellent antibacterial properties without compromising the product quality. Therefore, EW is extensively used in fruit processing due to its higher efficacy for disinfecting microorganisms. Graça et al. monitored no apparent difference in physical appearance, color, total soluble solids, and acidity between untreated and electrolyzed water-treated strawberries134. The commercial EW generator has been used in the food processing industry to produce EW. The efficiency of EW against microorganisms is mainly ascribed to exposure time, pH, available chlorine concentration (ACC), type of microorganism, fruits used, and temperature. It has been noted that the microbial populations sharply decreased after modulating the factors mentioned above, such as higher levels of ACC, lower pH, and stretched exposure time. Similar findings on the declined population rate of Gram-positive bacteria L. monocytogens were monitored by Rahman et al. where log CFU/g value surged from 4.98 to 7.42 upon hiking the temperature of EW from 4 to 50 °C135. However, post-EW treatment results in significant adverse effects on the nutrient content of the fruit. Zhang et al. found that despite having remarkable EW efficiency (strong acid) against microbes, its corrosive and unstable nature restricts its application136. Therefore, mild acidic and neutral EW has been widely used for various applications. Moreover, chlorine gas is produced and released during the process of making EW, which could pose operational issues137.

1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP)

1- Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) is an anti-ethylene synthetic plant growth regulator widely applied to slow the ripening of stored fruits where ethylene has a role. 1-MCP treatment decreases the senescence processes, reduces physiological disorder development, and inhibits color change of treated fruits138. In addition, 1 MCP treatment affects the respiration rate and ethylene production in treated fruits, thereby increasing the shelf life of fruits such as apples, cherries, citrus, grapes, pomegranates, and strawberries138. 1-MCP gas can be produced when α-cyclodextrin powder is dissolved in water for 20 to 30 min at 20 °C139. Also, the treatment of 1-MCP has no significant effect on the nutritional quality and flavor of treated fruits. As an ethylene action inhibitor, 1-MCP can significantly reduce fruit decay, but its effect on fruit pathogens remains unclear. However, it was found that when pear was treated with 1-MCP, the disease incidence caused by pathogens was decreased140. Although 1-MCP has been used in various countries to extend the shelf life of climatic-type fruits, for the successful commercialization of 1-MCP application its effective concentration, exposure duration, and type of fruits must be optimized141. In addition, 1-MCP treatment cannot be applied to all types of fruits.

Organic acids

Organic acids are a combination of natural compounds with a slightly acidic nature142. It has been observed that daily intake of organic acids is tolerable and does not affect human health143. Organic acids can work efficiently under varied temperature ranges to incapacitate a wide range of bacteria144. For decades, organic acids such as tartaric acid, acetic acid, citric acid, and lactic acid have been extensively used as food preservatives to extend shelf life. One recent application of organic acids that gathered much attention was its use for fruit sanitation. Rico et al. have found the unique mode of action of organic acids against microbes by lowering the cellular and environmental pH, eventually annihilating membrane transport and cell permeability145. In particular, organic acids are present in two forms in nature: undissociated and dissociated forms. The undissociated organic acids tend to infiltrate the microbial membrane to reach the microbial cell interior. Upon reaching, the undissociated organic acids molecule breaks into protons and charged anions. As a result, the pH of the microbial cell interior drastically drops from neutral to acidic, followed by obstruction of the cell metabolic process, intracellular enzyme deactivation, and electrochemical proton gradient exclusion across the cell membrane146. It has been well-documented that acids can trigger oxidative stress in bacteria. Mols and Abee observed that exposing Bacillus subtilis to acetic acid, lactic acid, and sorbic acid caused the generation of ROS, which in turn provoked cell death147. Wang et al. explained the mechanism of antibacterial activity for lactic acid148. Organic acids have been extensively used as fruit disinfectants. Park et al. observed that upon treating apples with 2% citric and lactic acid for 10 min, the growth of pathogenic bacteria decreased by 2.5- 3.5 log CFU/fruit149. It was noteworthy that organic acid treatment did not change the color of apples during storage. It has been reported that a few derivatives of organic acids exhibited excellent germicidal activity. Chen et al. found that 0.3% acidified sodium benzoate treatment (pH-2) on washed cherry tomato decreased Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Salmonella enterica populations by about 5, 6, and 5 log CFU/g, respectively without affecting its quality150. Therefore, it can be concluded that organic acids reduce microbial loads of fruit while retaining the product’s quality144. The efficiency of organic acids to disinfect the fruits profoundly depends on the concentration, acid types, fruit species, treatment time, and microbe species. Park et al. found that apples treated with 2% propionic, acetic, lactic, malic, and citric acid with stretched exposure time from 0.5 to 10 min reduced the growth of E. coli O157:H7 significantly149. E. coli O157:H7, S. Typhimurium, and L. monocytogenes treated for 10 min remarkably reduced their growth by around 1, 3, and 2.5 log CFU/fruit on apples, respectively149. Owing to the low antimicrobial properties of organic acids, high concentration and prolonged treatment time are recommended. In addition, a high concentration of organic acids can harm human tissue, cause corrosion in treatment equipment, and alter fruit odor and flavor151.

The above-mentioned emerging chemical disinfection techniques have immense potential to ameliorate fruit safety following standard protocols. However, complications associated with antimicrobial washes cannot be ignored; therefore, they should be adequately addressed. During the sanitizer washing process, ample water is required, eventually leading to pathogen cross-contamination and environmental pollution. The microbial population can be checked through rising concentrations of sanitizer or prolonged exposure time, but the standard quality of the product should not be compromised at the same time. Hence, it is imperative to optimize the treatment parameters first to properly balance substantial reductions in microbes without impacting the quality of fruits151.

Modified atmosphere packaging

In modified atmosphere packaging (MAP), fruits are packaged in an enclosed environment with optimum air concentrations and a different ratio of gasses other than normal atmospheric gas concentration152. In general, three primary gases such as nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxides are used in various ratios for MAP to decrease physiological damage, water loss, and microbial growth resulting in a higher shelf life of packaged fruits153. On the other hand, when the parameters of MAP are regularly monitored and controlled, the process is termed controlled atmosphere (CA) storage. The rate of respiration and metabolism of fruits can be minimized by decreasing the oxygen concentration in MAP, resulting in the late-ripening of fruits154. MAP has been applied to enhance the shelf life of various fruits such as apples, figs, grapes, pears, oranges, etc. Table 2 summarizes the optimum conditions of MAP and CA to prolong the shelf life of packaged fruits.

Nanoparticles and nanoemulsions

Nanotechnology stands as a significant breakthrough with vast potential for enhancing sustainability across various fields. Drawing from applied sciences including physics, biology, food technology, environmental engineering, medicine, and materials processing, it offers a versatile approach155. This technology is favored for its diverse properties, including slow-release action, target-specificity, precise action on active sites, and high surface area156. Its success can be attributed to promising outcomes, the absence of pollutant release, energy efficiency, and minimal space requirements. In addition to these factors, nanotechnology has demonstrated versatile applications in safety, toxicity assessment, and risk evaluation concerning food and environmental domains157.

Numerous fresh fruits are vulnerable to oxygen, water permeability, and ethylene exposure, which can degrade their quality over time158. Consequently, packaging plays a vital role in addressing these challenges. Nanoparticles and polymer-based composites have emerged as promising solutions in this regard159. Although the integration of nanomaterials into smart packaging is still in its nascent stages, significant progress has been made over the years, offering a safe and sustainable approach160. Nanocomposites, which combine various nanomaterials, exhibit efficient thermal and barrier properties at a low cost. Studies assessing nanocomposite membranes have shown a remarkable 46% reduction in water permeability in fruits161. Moreover, the use of clay and epoxy composites has demonstrated increased corrosion resistance162. Edible coatings incorporating nanomaterials hold significant potential for fruit storage, facilitating safe transportation from factories to retailers while maintaining nutritional quality and minimizing physical damage. Nanoclays and nanolaminates have also shown promise in enhancing barrier properties to gases for efficient fruit packaging163. Nanolaminates involve the deposition of a special coating layer by layer, with the charged surface applied to fruits. Carbon nanotubes as nanofillers in gelatin films have been successfully demonstrated, resulting in improved tensile strength, mechanical, thermal, and antimicrobial properties of biopolymer-based films164,165. Consequently, nanomaterials have become indispensable in the realm of fruit preservation. Additionally, nanoemulsions, which are oil-in-water or water-in-oil emulsions, offer notable advantages in improving the physicochemical properties of edible coatings for various food products166. Nanoemulsions, particularly those with oil-in-water emulsions, are evolving as next-generation edible coatings due to their compatibility with food-grade components and scalability in food industries using high-pressure homogenization. They find application as edible coatings for postharvest fruits like papaya, mango, and strawberries, enhancing the dispersion of active chemicals. For instance, nanoemulsions made from chitosan or nutmeg seed oil serve as effective coatings for strawberries, preserving quality and reducing microbial growth for up to 5 days of storage167. Essential oils, widely used as bioactive components in nanoemulsions for edible coatings, offer environmental benefits but are limited by their low stability and intense flavor, which can affect the sensory aspects of food products168. Encapsulating essential oils in nanoemulsions overcomes these limitations by enhancing stability and minimizing flavor impact168. The encapsulation of active components within matrix materials contributes to the enhanced functionality of edible films through encapsulation technology169.

Biological method

Essential oils

Essential oils (EOs) are naturally occurring secondary metabolites in plants with strong sensorial properties170. EOs possess antimicrobial, antiparasitic, UV light protection, and antioxidant properties171. The antimicrobial properties of EOs have long been studied as an alternative to synthetic compounds. The goal is to have a “clean label” on food. Essential oils contain phenolic compounds and terpenes that are aromatic and antimicrobial172,173. Most essential oils are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the US FDA and can be used in foods. Since the constituents of EOs are active against various microorganisms, they are an attractive option as a preservative174,175. Billing and Sherman compared the antimicrobial activities of spices and showed that 80% of them inhibited >75% of the bacteria tested, and 13% of the spices inhibited all tested bacteria176. Essential oils of cinnamon, oregano, bergamot, mountain savory, red thyme, and mustard were very effective against primary pathogens found in foods174,177. It was reported that EOs affect the integrity of bacterial membranes and induce loss of intracellular ATP, reduction of internal pH, alteration of intracellular enzyme activity, and loss of cellular constituents, and these reactions vary according to the types of EOs and microorganisms178. The antimicrobial activity of EOs depends on the composition of the cytoplasmic membrane of the microorganism179. The antibacterial properties of EOs are also associated with their lipophilic character, leading to their accumulation in membranes, an attack of membrane integrity, and an energy reduction180. At acidic pH, the EOs become more hydrophobic, thus offering better penetration through the bacterial membrane180. The hydrophilic/lipophilic equilibrium and the existence of a phenolic compound with a hydroxyl group form hydrogen bonds with the enzymes and inhibit them, causing microbial death. The position of the hydroxyl groups, solubility in lipids, and the degree of steric hindrance also determine the antimicrobial activity of the phenolic compounds181. Recently, the disinfection of fruits using EOs has been gaining interest at a fast pace because of their profound antimicrobial activity and eco-friendly nature182. Furthermore, it has been tested that a fruit’s firmness, texture, color, weight loss, and sensory properties do not change with EOs application171. Generally, microbial inactivation is greatly influenced by the concentration of EOs, treatment time, solubility of EOs, and types of microorganisms. Also, Gram-positive bacteria are comparatively more sensitive to EOs treatment compared to Gram-negative bacteria183. Most EOs are not soluble in water; therefore, emulsification technique have been applied recently to increase the solubility and antimicrobial activity of EOs171. In addition, as reported in various studies, a higher amount of EOs is required for in-vivo treatments to get a similar antimicrobial effect for the in-vitro test; however, higher concentrations of EOs have an organoleptic effect and significantly alter the taste and flavor of fruits14. Further research is needed on the cellular toxicity of EOs and their interaction in the human gut184. Also, the volatility of essential oils (EOs) poses a challenge for their direct application to fruit surfaces185. Consequently, incorporating EOs into polymeric coatings has become common practice to extend fruit shelf life. However, the high hydrophobicity of EOs makes achieving a uniform dispersion over the fruit surface difficult when simply added to coating formulations. To address this challenge, a delivery system designed to protect and release compounds at the appropriate time and location offers a viable solution. Emulsions, wherein two immiscible liquids form a mixture of spherical droplets (dispersed phase) within a surrounding liquid (continuous phase), provide a means to improve EO dispersibility and uniformity. Typically, essential oils are incorporated into coatings as oil-in-water (o/w) emulsions. Conventional EO emulsions, depending on concentration, can alter fruit color and flavor and may degrade under extreme environmental conditions (temperature, pH, oxygen, light, and moisture)186. Another drawback is the fast release of volatile compounds, which can impair their biological action on fruit preservation187. Nanoemulsions, featuring EO droplets on the nanoscale, have garnered attention for their functional and physicochemical properties. Nanoemulsion EO droplets can readily penetrate microbial membranes, disrupting their organization and promoting cellular content leakage and death, thereby enhancing antimicrobial efficacy166. EOs also exhibit potent antioxidant properties, scavenging reactive oxygen species and reducing oxidative stress induced by pathogen growth, thus extending fruit shelf life14,184. Certain phenolic compounds present in EOs, such as thymol, eugenol, and carvacrol, contribute to their antioxidant action188. Recent studies have highlighted EO’s role as a signaling compound, triggering defense mechanisms in fruits by enhancing enzyme activity, antioxidant capacity, and ethylene production189. Chrysargyris et al. reported that when mature green tomato fruit were subjected to EO-enrichment (sustained effect) were perceptibly retained their firmness in low EO levels (50 μL/L)189. However, the rates of respiration and ethylene as well as the antioxidant metabolism were increased in high EO levels of 500 μL/L, and the effects were more pronounced during the storage period of 14 days, in comparison to the control fruits (subjected to typical storage and transportation methods). Similar effects were observed in red tomatoes, where EO exposure led to changes in quality attributes190. The ripening stage and environmental stresses also influence ethylene production in fruits189. Further research is warranted to optimize EO application conditions (method, duration, concentration) for different fruits and scenarios.

Edible coating

Petroleum-based packaging materials have been extensively used for fruit packaging for the past few decades because they are economical, easy to produce, and easy to use, and they possess the required mechanical and barrier properties191. Consumers insist on moving towards using biodegradable, environmentally-friendly, and renewable packaging due to the safety concerns of petroleum-based packaging materials uses, because of their non-biodegradable and non-renewable nature, accumulation in the environment, as well as depletion of natural resources192,193. Therefore, edible film and coating are one possibility to fulfill consumer needs194. Edible films and coatings are fine deposits of eatable materials that might be removed during washing or eaten together with fruits and fruit products195. Edible coatings based on food-grade biopolymers possess an advantage over synthetic materials as they are biodegradable, cost-effective, environmentally-friendly, and edible196,197. Until now, various types of biopolymers have been used to prepare edible films and coating materials based on protein (whey protein, zein, soy protein), carbohydrates (alginate, agar, cellulose, chitosan, starch), lipids (paraffin, bee wax, edible oils)198. Klangmuang and Sothornvit demonstrated the reduction in the disease severity of mango by coating with hydroxypropyl methylcellulose incorporated with Thai herb essential oil199 (Box 2).

Carbohydrate-based polymers are hydrophilic and possess excellent film-making properties200. Regardless of the poor water vapor barrier properties of carbohydrate-based polymers, they form a gelatinous layer with high moisture that can retain the moisture of fruits201. The inherent antimicrobial properties of chitosan make it an ideal for edible coating to reduce the protect the fruits from microbial infection. Maqbool et al. demonstrated the control of anthracnose in banana (caused by Colletotrichum musae) by the combined effect of coating with gum arabic and chitosan at room temperature202. Lipids-based coatings have excellent water vapor barrier properties; however, they have low mechanical strength and low barriers to oxygen and CO2 because of their non-polymeric character203.

Protein-based coatings can be prepared from caseins, gelatin, whey, soy, zein, etc. They possess poor barriers to moisture201. Protein-based coatings and films form ionic, hydrogen, and covalent bonding among polymer chains, resulting in brittleness in nature and easy to crack153,154. Ranjith et al. reported the control of postharvest fungal growth in mango using peptide-based coating produced by palm-kernel cake fermentation204. Table 3 summarizes the different types of coating materials for fruit preservation.

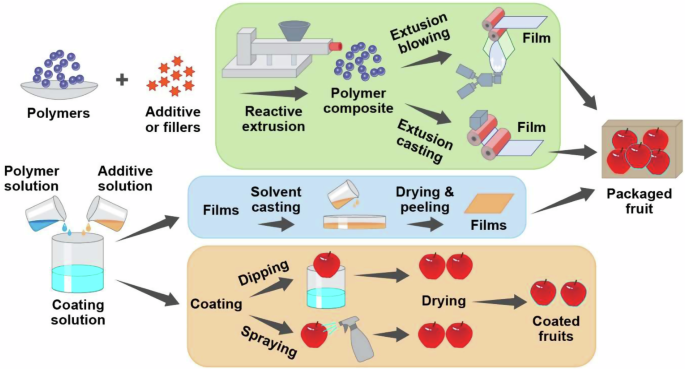

Figure 4 illustrates various coating and film material development methods for fruits, such as developing films by solution casting and extrusion methods and coating fruits by dipping and spraying methods at a laboratory scale196,205. However, new processing machines might be involved in the industrial-scale manufacture of coatings materials and films. The investment in new processing machines must be reasonable and should have the least variation from traditional machines for synthetic packaging.

First, the polymers (biopolymer or bioplastics) are mixed with additives or fillers (plant extracts, bioactive compounds, essential oils, nanoparticles, agricultural waste, food waste, inorganic fillers) by melt extrusion or in the form of a solution. The melt extrusion composite is further processed by extrusion casting or blowing to develop packaging films. Polymer composite solution can be used to prepare solvent-casting films or to coat fruits by dip coating or spraying. (Figure created using Microsoft PowerPoint).

The usual film-making techniques are solution casting and melt extrusion methods. Extrusion is a suitable method to manufacture films at an industrial scale through extrusion casting and extrusion blowing206. Extrusion methods involve high temperatures to melt polymers and film formation. In addition, the extrusion method is considered superior to the solvent casting method as it is eco-friendly with respect to a solvent-free system and low energy consumption207. However, the quality and quantity of bioactive compounds and browning of protein films by the Millard reaction may occur in the melt extrusion due to the high processing temperature208.

Dipping is a commonly used method at the lab-scale for coating fruits; however, it is time-consuming and there is the risk of getting dilution of coating solution with time. In addition, thickness of the coating layer cannot be controlled and accumulation of impurities in the dipping tank can result in microbial contamination and anaerobic fermentation205. Spray coating, on the other hand, can be uniformly applied on the fruit surfaces with controlled thickness. Nevertheless, it is important to take care of the viscosity of the coating solution, the interaction between droplets, and the aggregation of the droplets205. Recently, coating of fruits by electrostatic spray has become prevalent in the fruit industry208.

In the electrostatic spray method, the coating solution is sprayed out from the electrode with force by applying a strong electric field to the coating solution209. The electrostatic spray technology has superior control on the droplet size, can coat uniformly on the surface, has minimal waste, and has better coating efficiency at a large scale than the traditional spraying method207. Moreover, electrostatic spray coating can be used in continuous industrial operations at a lower processing expense209.

Edible coatings and films act as a carrier of various bioactive materials with antimicrobial, antioxidant, and nutraceutical properties110. Besides numerous benefits, possible adverse effects of edible films and coatings must carefully judged. For instance, low molecular weight carrageenans below 50 kDa are reported to be toxic at higher doses210. However, the molecular weight of food-grade carrageenan is more than 100 kDa and the quantity used in coating or as a food additive is much less than the toxicological concentration210. In addition, the impurities present in raw materials also need to be determined, such as the presence of heavy metals and endotoxins in alginate that may create an immunogenic response211. Furthermore, many people are allergic or intolerant to specific foods and get severe illnesses such as allergies to nuts, wheat gluten, milk proteins, seafood, etc. Also, some people do not eat particular types of food due to their religious faith. Hence, it is essential for the food or food packaging industries to label their product correctly so that consumers will be aware of its constituents212.

Bioagents

The antimicrobial effect of bioagents has been gaining popularity in controlling preharvest and postharvest diseases of fruits caused by microorganisms to reduce the use of synthetic bactericides or fungicides. Bioagents based on bacteria and yeast are the most efficient method of managing postharvest diseases of fruits213. Biological control employing bioagents holds significant promise. Key microbes such as Trichoderma viride, Trichoderma harzianum, Pseudomonas flourescens and Bacillus subtilis are efficient bioagents capable of producing biologically active metabolites like antibiotics, bacteriocins, and inducers of systemic resistance in plants214. To qualify as an ideal bioagent, a potential microbial antagonist should possess specific desirable characteristics, including genetic stability, efficacy at low concentrations, minimal nutritional requirements, resilience under adverse environmental conditions, effectiveness against a broad spectrum of pathogens and harvested commodities, resistance to pesticides, non-production of harmful metabolites, non-pathogenicity to the host, preparation in a storable and dispensable form, and compatibility with other chemical and physical treatments215. Additionally, a microbial antagonist should exhibit an adaptive advantage over specific pathogens. There are two primary approaches for utilizing microbial antagonists to control postharvest fruit diseases: (1) leveraging microorganisms naturally present on the product, which can be encouraged and managed, or (2) artificially introducing antagonists against postharvest pathogens216. Chalutz and Wilson found that when concentrated washings from the surface of citrus fruit were plated out on an agar medium, only bacteria and yeast appeared while after dilution of these washings, several rot fungi appeared on the agar, suggesting that yeast and bacteria may be suppressing fungal growth. This suggests that yeast and bacteria may suppress fungal growth, indicating that washed fruits and vegetables may be more susceptible to decay compared to unwashed ones217. Bhan et al. reported the mycelial growth inhibition of three filamentous pathogenic microorganisms of Kinnow mandarin such as Penicillium digitatum, Penicillium italicum, and Geotrichum candidum using Rhodotorula minuta var. minuta by 71.98%, 76.18% and 67.46%, respectively218. They also showed that the treated Kinnow mandarin fruits exhibited lesser decay and slower weight loss while maintaining total phenol, antioxidant activity, and sensory attributes. In another study, Hassan et al. reported the use of preen (uropygial) oil in combination with endophytic bacteria Bacillus safensis in controlling grey mold caused by Botrytis cinerea in strawberry fruits219. Bacillus safensis produces different enzymes such as proteases, hydrolytic lipases, and chitinase that cause hydrolysis of the cell wall of Botrytis cinerea and restrict their growth on treated strawberries. Moreover, the biocontrol potential of several other microbial antagonists has also been demonstrated in several fruits such as banana, mango, litchi, papaya, avocado, kiwi fruit, and jujube214. More attention needs to be paid to the commercial production of bioagents. The use of bioagents for controlling fruit spoilage microorganisms should be popularized at the University level to encourage more research on bioagents and their genetic engineering for improving selection and mass production.

Biomolecules

Brassinosteroids

Brassinosteroids (BR) are steroidal phyto-hormones, first discovered in the pollen of rape seed plants. Among BR, brassinazole, 24-epibrassinolide, brassinolide, and 28-homobrassniolide have been regularly used in the postharvest preservation of fruits220. For instance, 24-epibrassinolide treatments reduce decay and lower oxidative stress in Satsuma mandarin, slower senescence of kiwifruits, elevate lycopene content and greater degradation of chlorophyll contents in tomato, and enhanced accumulation of anthocyanins in strawberry fruits221,222,223,224. Zhu et al. studied the effect of BR on the blue mold rot of jujube caused by Penicellium expansum225. They reported that applying 5 µM of BR efficiently inhibits the growth of P. expansum. However, BR application did not exhibit a direct antimicrobial effect against P. expansum but significantly decreased fruit senescence by reducing ethylene production and maintaining fruit quality. It is suggested that the effects of BRs on reducing decay caused by P. expansum may be associated with the induction of disease resistance in fruit and delay of senescence. Thorough research is still needed on a crop-by-crop basis for BR application, as a few studies are contradictory. Some researchers reported that the exogenous application of BR stimulates ethylene production and speeds up ripening; however, another researcher indicated that BR application suppresses ethylene synthesis and ripening. The effect of BR on other hormones should be studied in more detail as it is usually ignored in postharvest storage studies of fruits

Melatonins

Melatonin, N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine (MLT), is a pleiotropic molecule with a wide range of cellular and physiological actions. Melatonin is an innovative bio-stimulator with various uses in postharvest physiology and other plant growth and development aspects226. Some studies have reported that MLT displayed antimicrobial activities against different fruit pathogens. Zhang et al. reported that MLT treatment in tomatoes successfully suppressed Phytophthora infestans and decreased the late blight symptoms of tomatoes227. In another study, Zhu et al. showed the antibacterial effect of MLT against Bacillus cereus, Bacillus licheniformis, and Bacillus subtilis on cherry tomatoes228. They reported that applying 10,000 μM MLT on cherry tomatoes decreased the B. cereus, B. licheniformis, and B. subtilis by 93, 100, and 95%, respectively.

Future perspectives

In summary, innovative non-thermal physical approaches render a mild pasteurization method that reduces microbial loads considerably and lessens the effect on the organoleptic and nutritional value of fruits. Many physical disinfection technologies, including ionizing irradiation, HHP, PL, and UV light, are being commercialized. In addition, the above-mentioned techniques are not cost-effective and user-friendly compared to chemical treatment. Initially, with low investment and set-up expense, UV light seems more budget-friendly (operating cost around $10000 to $15000) than PL, whose operation cost is very pricy (investment cost (300,000 to 800,000 Euros)229,230. As a result, the high capital expenditure restricts its application to high-value-added products. The initial capital expenditure for an ionizing irradiation facility is costly ($4 million to $10 million), but the subsequent cost for fruit ionizing irradiation processing is acceptable (~$0.10/kg)231. The commercial scale HHP vessel usually costs between $500,000 to $2,500,000 depending upon equipment capacity and extent of automation232.

Due to its eco-friendly and energy-efficient qualities, physical disinfection techniques have been utilized widely. It minimizes cost, reduces changes in fruit organoleptic, adds value to the product, and provides decent payback on capital expenditure in the long run. Some other technologies like cold plasma and high-intensity ultrasound have been explored at the lab scale with encouraging results, but the process is still in the novice stage. In addition, biotechnological and genetic engineering approaches could be utilized to develop a resistant variety against microbial pathogens. Techniques like gene editing allow precise alteration of fruit genomes to bolster disease resistance while maintaining nutritional quality and taste. Biotechnological advancements offer opportunities to identify and incorporate beneficial microbial strains into fruit cultivation practices, fostering natural defense mechanisms against pathogens. As research continues to innovate in this field, we can anticipate a future where fruits are not only healthier and more resilient but also sustainably cultivated, benefiting both growers and consumers. To exploit the application fully, several research attempts are required to devise large-scale budget-friendly equipment for the fruit industry. Novel approaches and schemes can be developed from basic knowledge such as omics studies, flow cytometry, and physiological studies to ascertain the mode of action of individuals and combined treatments. Furthermore, those strategies can be exploited for model development and process design. The pertinent information is available in scientific articles where a single factor or interaction of various factors that trigger microbial activities in food can be investigated. It is worth noting that assessment should be performed on its practical relevance upon formulating combined techniques. It is imperative to document and develop the models through systemic studies so that the dose-response of concerned microorganisms, native flora, and quality standard of single/combined factors can be optimized for the fruit to alleviate further obstacles.

Conclusions

The current physical and chemical disinfection technologies are the eminent candidates that showed an edge over conventional chlorine washing to check the microorganism growth on fruits. However, the above-mentioned technologies are exploited mostly alone, which might render an inadequate antimicrobial spectrum and influence a food product’s nutrition and organoleptic properties. Therefore, developing and adopting a combination technology such as the treatment of fruit with essential oils (EOs) in combination with gamma irradiation could be a viable alternative to ensure food safety, nutrition, and sensory qualities of fruits. The combination of EOs with gamma irradiation lowers the required dose of both EOs and irradiation. The combined or sustainable model promotes the sensible use of various preservation factors, skills, or technologies to reach multi-target and constant preservation effects. In particular, each component of combined technology works synergistically and hits multiple targets simultaneously within the microbial cells; as a result, it interrupts the function of microbial cells. In addition, several attributes of combined technologies, such as less amounts of antibacterial compounds for application, decreased operation intensities (frequency, dosage and power), and less exposure time, lessen the effect on fruit quality. Therefore, combined treatment technologies seem promising for obtaining safe, high-quality, and long shelf-life fruits.

Responses