Advocating microbial diversity conservation in Antarctica

Introduction

Antarctica, often depicted as a vast, remote, and pristine wilderness area providing useful analogues to locations outside our planet, is not devoid of life1, rather contains strong environmental gradients on the planet and therefore provides a natural laboratory to study the relevance of environmental variability for biodiversity2. Within and around its icy surface we encounter uniquely rich yet underexplored microbial communities that play a crucial role in sustaining the continent’s ecosystems. Despite their microscopic size, Antarctic microorganisms have a significant ecological influence, namely in driving nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration3,4. From the frigid expanses of polar ice caps to the brine-filled depths of subglacial lakes, to the seasonally deglaciated soils or the permanently arid ones of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, to Antarctic geothermal areas, these resilient organisms thrive in environments once considered inhospitable for life5,6,7,8,9. Recent reports have underscored the presence of diverse microbial communities even in Antarctic lakes, such as Lake Vida, where microorganisms thrive despite extreme cold and high salinity conditions10. Furthermore, research has highlighted the importance of Antarctic microorganisms in biotechnological applications, including enzyme discovery and bioremediation strategies11,12. In continental Antarctica, microbial communities are distributed along environmental gradients, primarily inhabiting coastal sites with more favorable conditions during the austral summer. Further inland, these communities are almost exclusively found in soils and rocks that are seasonally ice-free. In contrast, in tundra areas like maritime Antarctica, they are more widespread due to milder climatic conditions13,14.

Despite its isolation, the pristine nature of Antarctica is increasingly threatened by human activities, with studies documenting anthropogenic contamination even in the most remote regions of the continent. For instance, research conducted by Hughes et al.15 revealed the accidental transfer of non-native soil organisms into Antarctica on construction vehicles, highlighting the potential for human-induced disturbances in microbial communities. These non-native organisms included both macroscopic angiosperms, bryophytes, invertebrates, seeds, nematodes, and moss propagules as well as microscopic fungi and bacteria. A dataset on introduced and invasive alien species of Antarctica and the Southern Ocean Islands has recently been compiled16. This dataset includes taxa that have been recorded outside of their native range, native Antarctic species introduced to new areas within the region by humans, and those of unknown biogeographic origin. Only the well known groups of vascular plants, mammals, insects, birds, spiders, annelids, and springtails are included in this dataset. Thirteen percent of these species are considered locally invasive16. Because of the less extensive data on microbiota, invasive microorganisms were not included in the study. Whether non-native and pathogenic microbial species can be transported over long distances into the pristine interior of the continent remains unanswered. Antarctica also hosts a number of endemic species, as a result of its geographic isolation and evolutionary history, alongside many cosmopolitan cold-adapted species17. According to a study by Cox et al.18, where DNA and RNA were co-extracted from soils collected from three Antarctic islands, endemic and cosmopolitan fungal taxa exhibited differential abundances in total and active communities of soils (i.e., derived from their DNA and RNA profiles, respectively). Different dispersal strategies and adaptation abilities were postulated for cosmopolitan and endemic species, with the latter being more abundant in the active fungal community than in the total community. This increased abundance in the active community suggests that these endemic species are better adapted to the extreme environmental conditions encountered in the soils of the region and highlights the need for their protection, as they possess unique abilities to survive the stressful conditions of the area.

While Antarctica is generally considered one of the least impacted regions by human activities, it is challenging to identify locations which are entirely free of potential anthropogenic impacts. Human presence, even when in the form of scientific research stations, has the potential to introduce contaminants such as microplastics, pollutants, and non-native species15,19,20. Recent findings have revealed the presence of microplastics in Antarctic snow samples across the Ross Island region (continental Antarctica), indicating sources from both long-range and local transportation21. However, some areas, namely the Antarctic Specially Managed Areas (ASMAs) and Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPA) are more pristine and less influenced by human activities. These areas are designated to protect outstanding environmental, scientific, historic, aesthetic, or wilderness values, and they restrict human activities to minimise anthropogenic impacts22. These areas are selected based on their unique ecological or cultural significance and are managed to help maintain their pristine condition. Additionally, some remote and inaccessible regions of Antarctica, such as interior ice sheets and subglacial environments, are less affected by human activities due to their extreme conditions and limited accessibility. These areas may serve as reference sites for studying ecosystems relatively untouched by human interference. However, it is essential to recognise that the entire continent, including such remote regions, is not entirely free from potential anthropogenic impacts. In fact, long-range transport of pollutants, such as persistent organic pollutants and heavy metals, has been identified as capable of reaching even the most isolated parts of Antarctica through atmospheric and oceanic currents23,24.

However, while some areas may be less impacted, conservation efforts aim to minimise human influence across the continent to the greatest extent possible. By shedding light on the intricate web of life in Antarctica’s microbial realm, we underscore the urgent need for proactive conservation efforts to safeguard these invaluable ecosystems for the future of our planet. In this article, we embark on a journey to unravel the importance of conserving Antarctic microbial diversity amidst mounting threats posed by human activities, climate change, and burgeoning Antarctic tourism.

Importance of Antarctic microbial diversity in a time of climate change and tourism impacts

Based on data available from the SCAR Biodiversity Database, Antarctic terrestrial biodiversity is classified under 16 biogeographic regions (Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Regions, ACBRs), which are relevant for the identification of the ASMAs and the ASPAs. These classifications help address non-native species risks, particularly the transfer of species between locations in Antarctica associated with movement of people and cargo, by ship, aircraft, and overland travel25,26. The ACBRs represent a tool for biodiversity conservation planning. In this context, ASMAs and ASPAs serve as useful management tools, as they impose different forms of biosecurity27. Antarctica hosts a surprisingly rich microbial diversity in its cold desert soils. Metagenomic, biogeochemical, and culture-based analyses have unveiled both the phylogenetic and functional distinctiveness of Antarctic soil microorganisms, with a lower fungal and archaeal diversity than the bacterial one28. Microorganisms play a fundamental role in Antarctic soils, driving key biogeochemical cycling processes, despite the low temperatures28. There exists a diverse gene pool within these communities, allowing for metabolic flexibility and efficient functioning. This provides a pristine environment for studying the effects of climate change and exploring uncultured microorganisms with potential biotechnological applications29,30. Studies in various Antarctic regions highlight the altitudinal trends in microbial composition, functional capabilities, and trophic interactions, indicating the importance of altitude as a driver of microbial ecology in these environments31. Additionally, microbial communities in Antarctic snow ecosystems exhibit diverse enzymatic capabilities, suggesting their involvement in snow chemistry32. Research on Antarctic soils revealed a diverse array of metabolically versatile microorganisms capable of utilizing atmospheric hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and other inorganic compounds for energy production and carbon fixation33,34. Vegetation is pivotal in influencing the microbial diversity of Antarctic soils, as microorganisms interact with both vascular and non-vascular plants to aid their survival and growth in extreme environments. However, in continental Antarctica, differences were observed within soil microbial communities of coastal sites despite the apparent similarity in terms of non-vascular plant coverage. These differences were more driven by site-specific variations in environmental conditions, particularly edaphic factors35. Distinct microbiomes with limited overlap were recorded in soils of islands surrounding the Antarctic continent, shaped by the spatial isolation of the islands and their local environments36. Furthermore, several studies in maritime Antarctica have investigated the interactions between microorganisms and vascular plants, exploring their impact on the distribution, diversity, and abundance of native plants and microbial communities. These findings underscore the complexity and resilience of Antarctic microbial communities, which reflect a balance between generalist and specialist microorganisms37.

Studies on microbial diversity across various Antarctic habitats, using 16S rRNA sequence datasets, provide a baseline for understanding microbial responses to environmental conditions and future changes in Antarctica. Results indicate that each habitat (fumarole and marine sediments, soil, snow, and seawater environments) hosts unique microbial community structures, with specific taxa characteristic of each microbiome38. Marine sediments exhibited the highest microbial diversity. Fumarole sediments were dominated by thermophiles and hyperthermophilic Archaea, while Archaea were largely absent in soil samples. Seawater samples contained a core microbiome typical of Antarctic pelagic ecosystems. Snow samples showed common taxa found in the Antarctic Peninsula, suggesting long-distance dispersal to the Continent39. Microorganisms in Antarctica play fundamental roles in nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, and sustaining life in extreme environments. They inhabit various niches, from icy glaciers to subglacial lakes, as well as seasonally or permanently ice-free soils or rocks, contributing to the resilience and stability of Antarctic ecosystems4. Some Antarctic bacteria such as species of Marinomonas and Pseudomonas isolated from King George Island soil have been tested for use in metal bioremediation40. Research on microbial tolerance to heavy metals plays a crucial role in determining their potential use in biological wastewater treatment in colder and temperate climates, and in future biotechnological applications1,41. The white and solitary continent is covered with ice and glaciers but is also home to some highly active volcanoes, lava lakes and geothermal lakes hosting unique communities that warrant protection action primarily from an increasingly widespread tourism. Taking one of those examples and to relate that with necessity of biodiversity conservation, after the crash of an Air New Zealand DC-10 aircraft on a sightseeing flight over the Ross Sea into the slope of Mount Erebus on November 28, 1979, resulting in the deaths of 237 passengers and 20 crew members, and the inability to recover their bodies, the area was declared specially protected and kept inviolate as a mark of respect (Antarctic Specially Protected Area No 156). Numerous discussions on the feasibility of restricting tourism in Antarctica have arisen from this tragedy. Despite the recognition of the need for a tourism monitoring plan as early as 2009, little progress has been made over the past decade. Neither standard protocols for tourism monitoring nor methods for cumulative impact assessment have been developed thus far for the Antarctic Peninsula, where most Antarctic tourism is concentrated42. The knowledge about the human impact on Antarctica continues to grow steadily, but the quantification of the tourism industry’s contribution remains largely unknown43. A meta-analysis suggests Antarctic tourism has significantly increased and diversified. A total of 74,401 tourists visited Antarctica during the 2019-20 season, representing a 134% increase from the 2010-11 season a decade earlier44.

Antarctica boasting numerous geothermal sites with volcanic activity, provides ideal habitats for thermophilic and hyperthermophilic microorganisms. Deception Island, an active volcano in the South Shetland Islands (Maritime Antarctica) with a unique topography, is one such active geothermal environment. It harbours several thermophilic microorganisms, making it an attractive site for molecular studies related to industrial enzyme production45. These extremophiles are valuable sources of enzymes and bioactive compounds with biotechnological applications. Additionally, thermophiles and hyperthermophiles are found in diverse hot environments, including terrestrial and marine thermal sites, with some even thriving in lower temperature regions such as permafrost45. In that sense, Deception Island serves as one of the extraterrestrial analogues in our planet Earth46, further surging the necessity of conserving Antarctic microorganisms. Strategic management of Antarctic islands, such as Deception Island, is crucial. This island must be a priority in efforts to minimise environmental impacts, in alignment with the intention outlined in Article 3 of the Madrid Protocol47. Comparing the protected and non-protected areas of Deception Island, opportunistic, phytopathogenic and symbiotic fungi were detected, which might have been introduced by human activities or transported by birds and wind48. A similar trend has been observed among relatively undisturbed sites and sites heavily impacted by human visits for algal assemblage. The invasive species Caulerpa webbiana at Whalers Bay and the opportunistically pathogenic genus Desmodesmus were found at both sites49. Significant differences exist between protected and human-impacted sites on Deception Island regarding algal diversity, richness, and abundance50. The South Shetland Islands have experienced considerable effects of climate change in recent decades. Warming through geothermal activity on Deception Island makes this island one of the most vulnerable to colonisation by non-native species50. Comparing the resistance/tolerance (resistome) profiles of bacteria from anthropogenically impacted and non-impacted areas of the South Shetland Islands, impacted areas have more resistome genes than non-impacted areas51. Detecting the DNA of non-native taxa highlights concerns about how human impacts, primarily through tourism and research operations, may influence native microbial diversity.

Additionally, Antarctica is one of the most diverse continents for the non-vascular plant communities; two unique flowering species, sea birds and Antarctic animals´ breeding, impact on the microbial community might impact irreversibly their native microbiome in an era of climate change. Overall, the alert about the decline of pristine habitats in continental Antarctica has also been raised, mostly attributed to increasing research activities and the associated human footprint rather than tourists, who are mostly precluded from accessing the white continent. This growing human presence and disturbance pose a significant challenge for future research, as pristine environments—critical for conducting cutting-edge molecular analyses—are becoming increasingly rare. As a result, the potential of advanced molecular analyses in undisturbed Antarctic environment is diminishing52. The ability to use advanced molecular techniques in undisturbed microbial habitats is essential for accurate assessments of microbial diversity, yet the expansion of research stations and associated activities threatens these opportunities.

Threats to Antarctic microbial diversity

Air, soil and water contamination

Human activities, such as scientific research stations and transportation, have introduced contaminants and non-native microorganisms into the pristine Antarctic environment20,53,54. These pollutants can alter microbial communities, disrupt ecological processes, and pose risks to native species. For instance, oil spills and sewage discharge can damage microbial populations, leading to long-term ecological imbalances15. Moreover, studies have shown that microbial communities in Antarctic soils are susceptible to contamination from heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants55. Although it may be difficult to identify the impact of non-pathogenic microorganisms, there is evidence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) throughout the Antarctic continent and South Shetland Islands against all natural, semi-synthetic, and synthetic antimicrobials, which can be both natural AMR or human-introduced56,57. Notably, multidrug-resistant bacteria have also been identified in Antarctic birds58. Numerous studies have also demonstrated the presence of both culturable coliforms and other human faecal bacteria in the vicinity of research stations and their effluent outfalls56,59. Plastic pollution is an issue in Antarctica60 and might have unexpected impacts. Plastics of different particle sizes and polymeric compositions have been retrieved from Antarctic Sea ice, surface water, soils, sediments, and from terrestrial and marine organisms61. These plastics are suitable substrates for adherence and colonization by microbial communities and can serve as carriers for the spread of various species of microorganisms, including potential pathogens and antibiotic-resistant bacteria62. The aforementioned aspects highlight the urgency in addressing this issue both for wildlife conservation and public health in this region.

Climate change

Antarctica is experiencing rapid environmental changes due to global- and local-scale climate change, including rising temperatures, melting ice shelves, and altered precipitation patterns. These shifts directly impact microbial habitats, causing habitat loss, changes in microbial community composition, and increased competition among species. Endemic species may be particularly threatened by climate change. An example is represented by the two endemic psychrophilic species of Cryomyces (class Dothideomycetes), C. minteri and C. antarcticus, both isolated from cryptoendolithic communities in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. These species are highly specialized and have poor competitive abilities, making them vulnerable to disappearing if conditions become more permissive, allowing the introduction of less specialized and more competitive species from other latitudes63.

Research indicates that warming temperatures promote cyanobacterial growth in Antarctic soils, thus altering nutrient cycling dynamics and ecosystem functioning64. Additionally, bacterial communities appeared to be more affected by the rapid warming of the Antarctic continent than fungal communities, with implications for key steps in the nitrogen cycle65. Climate-induced changes in nutrient availability and UV radiation levels also stress Antarctic microbial populations66. Alterations in diversity of fungal communities because of climate change could have substantial effects on ecosystems, particularly those characterized by a low number of species. Maritime Antarctica is experiencing rapid warming phenomena, and warmer habitats have been shown to be characterized by higher diversity. There is an estimated risk of 20–27% increases in fungal species richness in the southernmost soils by 2100, which could have effects on nutrient cycling and, ultimately, productivity in the species-poor soils of maritime Antarctica67. Some ecological studies have been carried out to analyse the effects of climate change on single species as well. The majority of the terrestrial Antarctic microorganisms have long been known to have wide growth temperature ranges, which make them well adapted to the wide temperature variations of the Antarctic environment68. Despite this, increasing temperatures have been reported to have inhibitory effects on the growth and extracellular activities of Pseudogymnoascus roseus, known as a widespread Antarctic soil fungus69. Diurnally fluctuating temperatures have also been found to reduce mean growth rates of isolates of this species, while having few effects on specific β-glucosidase activity, a proxy measure for metabolic activity70. Marine microorganisms would also be impacted by the warming of the Antarctic Peninsula region. Using machine learning tools to predict the impact of rising sea surface temperatures on Southern Ocean microbial communities, a recent study suggested a loss of bacterial and archaeal diversity, coupled with a decrease of important bacterial and archaeal taxa involved with crucial biogeochemical processes71. On the other hand, a study that investigated how simulated tropical conditions could affect the microbial composition and the bacterial diversity in Antarctic soils from King George Island and Deception Island, showed that after incubating the soils under tropical-like conditions for 12 months, changes in bacterial diversity were observed, with increased abundance of certain potentially harmful bacteria, namely species of the genera Mycobacterium, Massilia, and Williamsia. However, most bacterial phyla did not adapt well to the simulated tropical conditions, indicating a loss of bacterial diversity in Antarctic soils after the incubation period72. This suggests that in a significant global warming scenario many Antarctic bacteria would have difficulty surviving.

One of the most evident effects of climate change in polar and high-altitude regions is deglaciation. It exposes terrestrial ecosystems that have been locked under ice for thousands of years to external environmental conditions, such as winds, solar radiations, and temperature changes. These areas are pioneer sites for soil formation and microbial colonization and succession, providing a unique chronosequence to assess microbial and plant colonization on previously uncolonized substrates and to study the response of microbial community to climate-driven environmental changes73. In the Larsemann Hills of East Antarctica, some abundant bacterial taxa were found to correlate with deglaciation-dependent soil moisture, pH and ion concentration in two different glacier forefields74. In a subsequent study in the same area, it was revealed that abundant bacteria were more sensitive to environmental changes than rare bacteria, with ice thickness identified as the most influential factor affecting the community structure of abundance75. An interesting study that explored bacterial, fungal and algal communities on different substrates, such as moraine rocks and soil at the Hurd Glacier forefield (Livingston Island, Antarctica), demonstrated contrasting succession patterns between edaphic and lithic microbial communities, which were associated with soil development and non-vascular plants colonization from the start of succession76. Glacier retreats due to climate change have potential implications for marine ecosystems as well. Changes in various communities have been studied, including the assemblages of benthic diatoms77 and ascidian communities78 in Marian Cove on the West Antarctic Peninsula, as well as the phytoplankton communities in Admiralty Bay, King George Island79. Finally, climate change may have an effect on potential dispersal processes and increase the risks of microbiological invasions. The bacterial diversity of air samples around the Antarctic continent was studied and compared to that of non-polar ecosystems80. In this study, it was indicated that the polar air mass over the Southern Ocean could act as a selective dispersal filter. At the same time, it suggested that the bacterial diversity of the region may be sensitive to changes in atmospheric conditions, which could potentially alter the existing pattern of microbial deposition in Antarctica.

Tourism impacts

Among the 16 biogeographical conservation regions in Antarctica, region 3-Northwest Antarctic Peninsula has been the most visited bioregion since 2015, with visits increasing from 125,000 to over 1 million persons for the 2022 to 2023 season81. Such heavy traffic can generate impacts on microbial diversity due to exposure to both biological and chemical contamination. The Antarctic Treaty System (https://www.ats.aq/) does provide guidelines for tourists and expedition organizers, which are compiled in the Manual of Regulations and Guidelines Relevant to Tourism and Non-Governmental Activities in the Antarctic Treaty area, adopted by ATCM XLIII through Decision 6 (2021), aimed at preventing the impacts of tourism in Antarctica. However, it is currently not possible to know how tourism will develop in the future and how it will impact on Antarctic microbial richness. Tourism growth in Antarctica brings opportunities for education and economic benefits but also adds significant challenges for microbial conservation. Foot traffic, waste generation, and inadvertent introduction of non-native species by tourists can disturb fragile ecosystems and disrupt microbial communities. Without stringent regulations and sustainable tourism practices, these activities could jeopardize the integrity of Antarctic microbial diversity via continuous anthropogenic impact bioaccumulation82.

Current conservation status and protected areas for Antarctic microbial ecosystems

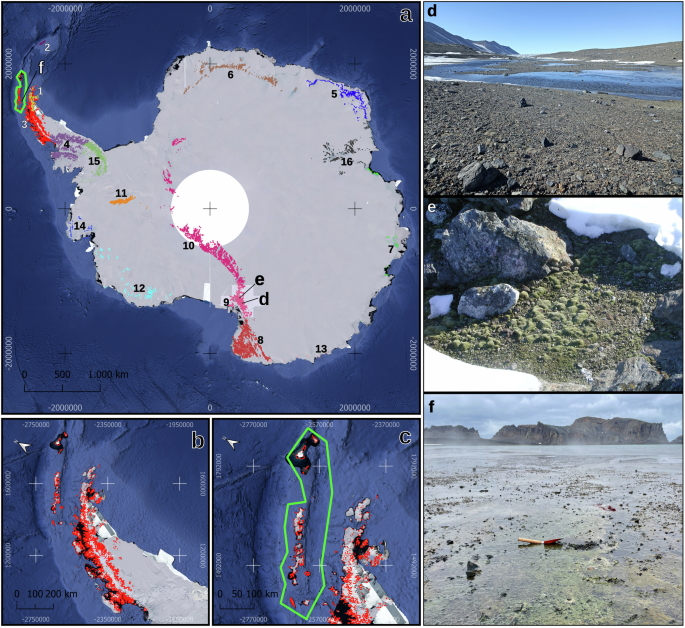

In the Antarctic Treaty System, specially protected areas were first established in 1964 under the Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora. Earlier categories of protected areas were then replaced in 1992 by Annex V to the Environment Protocol, which entered into force in 2002. This annex provides for the designation of two distinct protected areas: the Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs) and the Antarctic Specially Managed Areas (ASMAs)83. Additionally, a list of Historic Sites and Monuments (HSMs) were established in 1972 to protect sites of historic interest. An area in Antarctica can be designated as an ASPA to protect its environmental, scientific, historic, aesthetic, or wilderness values, or for ongoing or planned scientific research. An area where activities are being or may be conducted in the future can be designated as an ASMA to assist in planning and coordinating activities, avoiding conflicts, improving cooperation between Parties, or minimizing environmental impacts83. At present, there are 72 designated ASPAs, six of which are marine. ASPAs are located mainly within the Antarctic Peninsula and its offshore islands and archipelagos, the Ross Sea region and on various coastal ice-free areas of East Antarctica84. The Antarctic Peninsula, the most visited bioregion harbour 28 ASPAs, most of which are located in the west of the Peninsula. The management plans of each of the 28 ASPAs were reviewed, and it was evidenced that there is no valorisation of microorganisms (bacteria, archaea, and fungi) as an important aspect to be protected, except for ASPAs 126 and 149, located on Livingston Island of South Shetland Islands. Both ASPA and ASMA require a management plan and entry permission, but ASPA mandates it while ASMA does not. It is important to note that almost none of the designations explicitly include the value of microorganisms for special protection in the Antarctic territory. The values primarily focus on the protection of avifauna, flora, fauna, or marine species. Therefore, these ASPAs present an opportunity to study the role of microorganisms in areas with low human impact. All management plans for the ASPAs for the Peninsular Antarctica only establish that the deliberate introduction of microorganisms into the ASPA is restricted (https://documents.ats.aq/recatt/Att004_e.pdf). Map of the Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Regions (ACBRs), adapted from Terauds85 is presented in Fig. 1 along with the visual representations of some Antarctic sites with huge microbiological diversities.

a Antarctic continent and 16 ACBRs, b ACBR 3, located in the northern part of the Antarctic Peninsula, is the most visited biogeographic region by tourists and c South Shetland Islands, Pictures of (d) Onyx river, Lower Wright Valley, McMurdo Dry Valleys, Southern Victoria Land, e diffuse moss colonization at Kay Island, Northern Victoria Land, and f microbial mats at Deception Island. The 16 bioregions: 1) North-east Antarctic Peninsula, 2) South Orkney Islands, 3) North-west Antarctic Peninsula, 4) Central south Antarctic Peninsula, 5) Enderby Land, 6) Dronning Maud Land, 7) East Antarctica, 8) North Victoria Land, 9) South Victoria Land, 10) Transantarctic Mountains, 11) Ellsworth Mountains, 12) Marie Byrd Land, 13) Adelie Land, 14) Ellsworth Land, 15) South Antarctic Peninsula and 16) Prince Charles Mountains.

The Byers Peninsula (ASPA 126) at the Livingston Island is the only area that has a section dedicated to microbial life in its management plan. Furthermore, it is the only one on the Antarctic Peninsula that presents “Restricted and managed zones within the Area”. Some zones on Byers Peninsula are thought to have been visited only very rarely, or never. New metagenomic techniques are allowing the identification and characterization of microbial diversity (bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses) from all kinds of samples86, facilitating the resolution of many fundamental questions regarding microbial dispersal and distribution. Restricted zones have been designated for their scientific importance to Antarctic microbiology, with access further restricted to prevent contamination by microorganisms or other substances resulting from human activity. On the other hand, ASPA 149, also located on Livingston Island, mentions microbial ecology. Field studies of the microbial ecology at Cape Shirreff were carried out in 2010 and results were compared with the bacterial communities present at Fildes Peninsula, King George Island. The study aimed to evaluate the influence of the different microhabitats on the biodiversity and metabolic capacities of bacterial communities found at Cape Shirreff and Fildes Peninsula87,88. Furthermore, the management plans of ASPAs 113, 139, 176, 117 indicate that there are no studies of microorganisms, while ASPA 107 indicates that microorganisms should be investigated in detail, and ASPA 115 mentions values that require protection. The shallow clayey soil at the Lagotellerie Island under the vegetation, and the invertebrate fauna and associated microbiota are mentioned to be unique at this latitude. Very exceptionally, ASPA 129, Punta Rothera, Adelaide Island, is designated as a control area for monitoring the effects of anthropogenic impact associated with the adjacent Rothera Research Station (United Kingdom) in an Antarctic tundra ecosystem. This can also be an opportunity for the study of microbial life, its role, and its evolution over time87.

There are many references to microbial communities or microbial taxa in the descriptions of ASPAs in Continental Antarctica, along with measures to preserve microbial or vegetation diversity. However, a few cases annotated these communities or taxa as reasons for ASPA designation. One such example is ASPA 138 (Linnaeus Terrace, Asgard Range, Victoria Land), which exhibits novel cryptoendolithic communities, from which the first endolithic fungal endemic species, Cryomyces antarcticus, and Friedmanniomyces endolithicus were isolated and described89. Furthermore, a unique microbial community has been reported in ASPA 172 (Lower Taylor Glacier and Blood Falls, McMurdo Dry Valleys, Victoria Land). Due to its high iron and salt content, and its location beneath glacier ice, the microbial ecosystem at Blood Falls is considered an important site for astrobiological analogue studies90. Furthermore, the primary reason for designating high altitude geothermal sites in the Ross Sea region as ASPA 175 is to protect the outstanding ecological values, specifically the unique biological communities that occur in an environment where the selective factors are unique resulting in an assemblage of organisms not found anywhere else in the world. The main characteristics of the ASPAs from Antarctic territory mentioned in this manuscript is mentioned in Table 1. The microbial communities of these geothermal sites, still poorly characterised, host some extremophiles that are recognised as useful for understanding the evolution of life, as the first inhabitants of Earth possibly evolved in extreme habitats91.

Despite various forms of protection being established, a recent study has highlighted the importance of identifying factors influencing ASPA effectiveness to design a better management system for Antarctic protected areas, especially in the context of rapid climate change92. Complete species inventories are critical for comprehensive investigations of the prevailing biological patterns and processes in the region. Very recently, the TerrANTALife 1.0 Biodiversity database has been established, containing many of Antarctica’s terrestrial and freshwater life forms, including various animal species, plants, fungi, protists, prokaryotic and viral taxa93. Other public repositories, such as the NCBI and ENA, are available where one can find several Antarctic microbial datasets. Such repositories are especially relevant for the planning of effective conservation strategies. Varliero et al.94 recently underlined that many datasets exist supporting the classification of Antarctica into different biogeographic areas, although they are mostly dominated by eukaryotic taxa, with contributions from the bacterial domain restricted to Actinomycetota and Cyanobacteriota. Considering this, they generated a comprehensive phylogenetic dataset of Antarctic bacteria with wide geographical coverage across the continent and sub-Antarctic islands, observing that the current ACBR subdivision of the Antarctic continent does not fully reflect bacterial distribution and diversity. This further confirms the importance of having datasets from online repositories and highlights that further studies are required to better characterize Antarctic soil microbial communities to investigate whether bacterial diversity and distribution is reflected in the current ACBRs.

Key conservation strategies

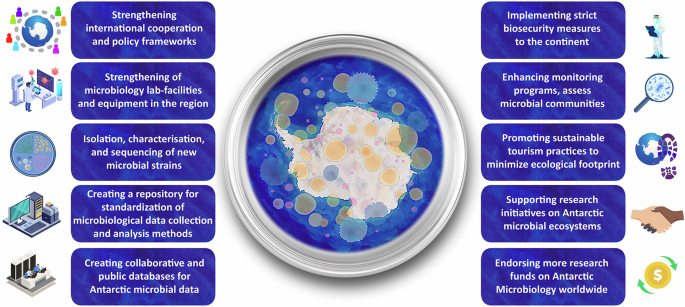

To mitigate the threats facing Antarctic microbial diversity, collaborative efforts are imperative for improving knowledge of the Antarctic ecosystem. We propose that the top ten key conservation strategies (summarised in Fig. 2) in Antarctica should include:

-

1.

Implementing strict biosecurity measures to prevent the inadvertent introduction of contaminants and invasive species. This includes standardised thorough screening and cleaning of equipment, supplies, and staff clothing, such as shoes, before they enter the continent.

-

2.

Enhancing monitoring programs with species distribution models like the other continents to determine base-line levels and changes in different types of key microbial environments in Antarctica (e.g., via the establishment and/or extension of time-series to incorporate microbiology) and assess the health and resilience of microbial communities. In this way, changes can be detected early and inform adaptive management strategies.

-

3.

Promoting sustainable tourism practices through education, regulations, and visitor guidelines, and enforce regulations to minimize the ecological footprint of tourism activities. Developing and disseminating clear visitor guidelines could ensure responsible behaviour to all visitors, including tourists and scientists.

-

4.

Supporting research initiatives to better understand Antarctic microbial ecosystems and their responses to environmental changes. In the light of the coming UN decade for the cryosphere and the international polar year, allocating resources to foster interdisciplinary collaborations will address knowledge gaps effectively.

-

5.

Endorsing more research funds on Antarctic microbiology worldwide and improving the Antarctic Specially Protected Area (ASPA) for microbial conservation.

-

6.

Strengthening wider collaboration, international cooperation and policy frameworks to prioritize microbial conservation as a fundamental component of Antarctic environmental protection. Part of this effort should be anchored on increased integration and cross-collaboration between different Antarctic programs and cross-use of facilities. Flagship of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) to incorporate microbial diversity conservation plans in polar areas as a future sustainable development goal.

-

7.

Strengthening of microbiology lab-facilities and equipment in the region, with a pooling of joint resources across scientific bases.

-

8.

Further emphasis on isolation, characterisation, and sequencing of new microbial strains, with strain and data deposition in public repositories as a way of capturing and preserving part of the unique microbiota and genetic material present in this continent.

-

9.

Creating a repository for standardization of microbiological data collection and analysis methods, including both culture-independent and dependent approaches.

-

10.

Creating collaborative and public databases specifically for Antarctic microbial data, highlighting the detection of potentially pathogenic and non-native taxa according to georeferenced metadata.

Schematic image depicting the Key Conservation Strategies for Antarctic Microbial Diversity.

Microbiological adaptation over ~25 million years in an isolated environment like Antarctica gives important hints on life frozen over time, evolution of earth´s earliest life forms, and additionally provide astrobiological insights into life in possible extraterrestrial ecosystems95,96,97. By implementing stringent key microbial conservation strategies collectively and comprehensively, we can enhance the protection of Antarctic microbial diversity and ensure the long-term health and resilience of these unique ecosystems. Since microorganisms interact with other organisms (flora and fauna) and play crucial roles in ecosystems that are also dominated by them, they should be also considered within general conservation plans making it an integrated broader conservation plan.

Conclusion

Preserving microbial diversity in Antarctica is critical for its ecosystems, aligning with an increasingly urgent global necessity. By conserving these invaluable organisms, we ensure the continued functioning of Antarctic ecosystems amidst growing anthropogenic pressures and climate change. Antarctica harbours a rich terrestrial and marine microbial realm vital for ecosystem functioning. These resilient organisms thrive in extreme conditions, influencing nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration. However, human activities and their consequences pose a rising threat to their habitats. Strict biosecurity measures, enhanced monitoring, and sustainable tourism practices are crucial for conservation. In addition, collaborative research efforts are vital to better understand Antarctic microbial ecosystems. By prioritizing microbial conservation, strengthening international cooperation, and integrating protection plans into policy frameworks, we can safeguard these invaluable ecosystems for future generations. Together, we must ensure the long-term protection and sustainability of Antarctic microbial diversity.

Responses