Alterations in PD-L1 succinylation shape anti-tumor immune responses in melanoma

Main

The immune system acts as a key defense against tumorigenesis, but tumors have evolved mechanisms to escape immune surveillance by altering the immune microenvironment, complicating effective eradication1. Blockade therapies targeting immune checkpoint proteins, such as programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) and its ligand PD ligand 1 (PD-L1), have revolutionized cancer treatment, notably extending survival across various tumor types2. Nevertheless, response rates to anti-PD-L1 or PD-1 monoclonal antibodies remain suboptimal, with only 15–25% of patients across diverse tumors responding positively3. Moreover, approximately one-third of initial responders relapse, underscoring the incomplete understanding of the immune checkpoint pathway’s mechanisms4. Identification of predictive biomarkers and resistance mechanisms is thus essential for enhancing the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade therapy.

Recent studies have highlighted the substantial influence of tumor metabolism on anti-tumor immunity. Tumor-derived metabolites, such as lactate, impair T cell function5, whereas shifts in metabolite composition affect T cell activation and metabolic reprogramming6. However, the role of tumor metabolism in immune cell function remains unclear. Tumor metabolism, marked by abnormal levels of metabolic byproducts, may contribute to an immunosuppressive microenvironment.

Beyond energy production, mitochondrial metabolism regulates protein functions through post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as acetylation, malonylation and succinylation7,8. Succinylation, a conserved PTM, involves the transfer of a succinyl group from succinyl-CoA to lysine’s ε-amino group9. Succinyl-CoA is produced via oxidative decarboxylation of α-ketoglutarate (AKG) by oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) or by reversible conversion of succinate through succinyl-CoA synthetase (SCS)10,11. Although both acetylation and succinylation affect similar lysine residues, succinylation adds a negative charge, producing a more substantial impact on protein function12. Studies have identified mitochondrial enzymes, such as succinylation of pyruvate kinase M2, undergoing succinylation, which subsequently enhances ATP production and aids cell survival under nutrient scarcity13. Protein succinylation is regulated by acyltransferases, deacetylases and coenzyme A (CoA) transferases, with carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A), a succinyltransferase, modulating enzymes such as endonucleases and S100A11 (refs. 14,15,16,17). However, the role of succinylation in tumor immunity remains poorly understood.

In the present study, we show that high expression of OGDH, SCS and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in tumor cells accelerates succinyl-CoA consumption, stabilizes PD-L1 and suppresses anti-tumor responses. PD-L1 succinylation induces its degradation via the endosomal–lysosomal pathway, thereby enhancing CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity. CPT1A, a succinyltransferase, mediates PD-L1 succinylation, promoting its degradation and facilitating CD8+ T cell activation. The combined expression levels of CPT1A and PD-L1 serve as a diagnostic marker, improving predictive accuracy for response to anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy. The present study identifies a potential biomarker for immune checkpoint blockade efficacy and proposes a new therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment.

Results

Succinyl-CoA shapes anti-tumor immunity

To explore mitochondrial metabolism’s role in tumor immunity, proteomic data from individuals with melanoma treated with immunotherapy were analyzed18. High expression of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle) and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) pathways correlated with improved prognosis (Fig. 1a) and better immunotherapy response (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Enzymes involved in OXPHOS and the TCA cycle were positively correlated with immune cell infiltration and activated CD8+ T cells at both the transcriptomic and the proteomic levels (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1b), suggesting a link between oxidative metabolism in tumor cells and anti-tumor immunity. The key enzymes bridging the TCA cycle and OXPHOS (OGDH, SCS and SDH; Supplementary Note) were abundant in immunotherapy responders and correlated with better outcomes (Fig. 1c). Patients with high expression of all three enzymes (Three_Complex_high) were more likely to respond to immunotherapy and had significantly better prognoses (Fig. 1d,e). These observations suggested that high enzyme expression might lead to abnormal metabolite levels, such as AKG or succinate, contributing to tumor immunity. In immunocompetent mice, treated with AKG (dimethyl α-ketoglutarate (DMK)) and succinate (diethyl succinate (DES)) suppressed tumor growth in melanoma (B16F10 or B16F10-OVA), colon cancer (MC38) and lung cancer (LLC) without affecting body weight (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 1c–i and Supplementary Note) and prolonged survival (Fig. 1g). Post-treatment analysis showed increased succinate and AKG levels in tumors and plasma, with minimal changes in other organs (Fig. 1h, Extended Data Fig. 1j and Supplementary Note), suggesting that these analogs, despite nonspecific cell entry, may exert distinct effects depending on the intrinsic metabolic profiles of different cells. Flow cytometry showed increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells and activated CD8+ T cells (CD8+GZMB+) (Fig. 1i and Extended Data Fig. 1k–m.), but no significant changes in myeloid-derived suppressor cells, regulatory T cells or macrophages (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Fluorescent multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC) revealed an increase in GZMB+CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) after DES and DMK treatment (Fig. 1j; Supplementary Note). Although previous studies linked succinate and AKG to macrophage polarization19,20, no changes were observed in macrophages from various tissues (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Depletion of macrophages with clodronate liposomes did not affect the efficacy of DES or DMK (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d). Treatment with the SDH inhibitor dimethyl malonate (DMM) also suppressed tumor growth, activated CD8+ T cells and prolonged survival (Extended Data Fig. 2e–g), suggesting that AKG metabolism to succinate is critical for anti-tumor immunity. Further experiments using an anti-CD8α antibody to deplete CD8+ T cells showed no significant effect on tumor growth on DES or DMK treatment (Fig. 1k and Extended Data Fig. 2h,i), with high doses inhibiting cell proliferation in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 2j). Spatial and single-cell transcriptomic analysis of melanoma revealed high expression of OGDH, SCS and SDH in malignant tumor cells (Mal) compared with the tumor boundaries (Bdy) and nonmalignant cells (nMal) (Fig. 1l, Extended Data Fig. 3a–c and Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that metabolite analogs primarily affect tumor cells directly.

a, Univariate Cox’s regression analysis revealed the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and cancer hallmark pathways linked to survival of patients with melanoma (n = 154 patients). E2F, E2 promoter binding factor. b, Heatmaps showing Spearman’s correlation between OXPHOS or TCA cycle and CD8+ T cells based on TCGA data, with correlation strength (Rs) and significance (FDR) indicated. c, Upper, eight critical enzymes driving the TCA and OXPHOS. Middle, protein expression differences of these enzymes in clinical responders (Rs, n = 65 patients) and nonresponders (NRs, n = 69 patients). Lower, associations of these enzymes with patient survival via univariate Cox’s models. d,e, The proportion of patients with different treatment responses to immunotherapy (d) and Kaplan–Meier curves showing OS (e) among the three complexhi groups and other groups receiving PD-1 or tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte immunotherapy in the proteomics cohort (n = 154 patients). f, Tumor volume measurements after DMK or DES treatments in mice (n = 5 per group). g, Survival analysis of mice after treatment with DMK or DES (n = 7). h, Succinate and AKG levels in tumor cells from DMK- or DES-treated mice (n = 4 per group). i, Quantification of CD8+/CD3+ and GZMB+/CD8+ CTL percentages in tumor masses (n = 5 per group). j, Immunostaining of CD3, CD8,and GZMB in B16F10 tumors (n = 5 per group). Scale bar, 100 μm. k, Tumor volume measurements after CD8+ T cell depletion and treatments (n = 5 per group). l, Spatial transcriptomic heatmap of OGDH, SCS and SDH expression in tumor regions. Scale bar, 0.65 mm. m, Schematic of succinyl-CoA production pathways. n, Succinate and AKG levels in A375 cells treated with metabolite analogs (n = 5). o, A375 cells treated with glycine and metabolite analogs, co-cultured with T cells, followed by Crystal Violet staining (n = 3). p, Succinyl-CoA levels measured by LC–MS in A375 cells (n = 4). For details on visualization, statistics and reproducibility, see Methods. Note, in a–n, n represents biologically independent samples and, in o and p, independent experiments.

Source data

To assess the effects of DES and DMK on different cell types, mouse tumor and immune cells were co-cultured and treated with these compounds. Analysis showed that the levels of succinate and AKG were more markedly elevated in tumor cells than in immune cells (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Therefore, it is probable that DES and DMK may enhance anti-tumor immunity by increasing these metabolites in tumor cells. To investigate further, these analogs, SDH and OGDH inhibitors, modulate metabolite flux and elevate intracellular succinate or AKG levels (Fig. 1m,n), followed by T cell-killing assays (Supplementary Note). DES or DMK exhibited increased T cell-mediated cytotoxicity, as shown by Crystal Violet staining, whereas tumor proliferation was unaffected in the absence of T cells (Supplementary Note and Extended Data Fig. 3e). Treatment with the reversible SDH inhibitor DMM and the irreversible inhibitor 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NPA), which covalently binds to an arginine residue in the catalytic core of succinate dehydrogenase A (SDHA)21,22 to inactivate SDH, resulted in intracellular succinate accumulation, decreased fumarate and enhanced T cell-mediated tumor cell killing (Extended Data Fig. 3f,g). However, the OGDH inhibitor (CPI-613) reduced T cell cytotoxicity, suggesting that AKG is converted by OGDH into downstream metabolites that bolster tumor immunity (Extended Data Fig. 3h)23. These metabolites are most probably succinyl-CoA and succinate, because succinate also increases intracellular succinyl-CoA levels through a reversible reaction catalyzed by SCS24. In addition, glycine can reduce succinyl-CoA levels via the heme synthesis pathway25. Co-treatment of tumor cells with glycine and SDH inhibitors (DMM and 3-NPA), DES or DMK significantly inhibited T cell cytotoxicity (Fig. 1o). Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) confirmed that these treatments increased succinyl-CoA, whereas glycine reduced succinyl-CoA levels (Fig. 1p). Hemin synthesis was also elevated with glycine and DES or DMK (Extended Data Fig. 3i and Supplementary Note). Tumor samples from mice treated with DES and DMK showed significant increases in succinyl-CoA (Extended Data Fig. 3j). OGDH knockdown or glycine administration promoted tumor growth and suppressed CD8+ T cell activation in vivo (Extended Data Fig. 3k–p). These results suggest that elevated intracellular succinyl-CoA enhances T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity.

Succinyl-CoA enhanced CTL activity by decreasing cancer cell PD-L1

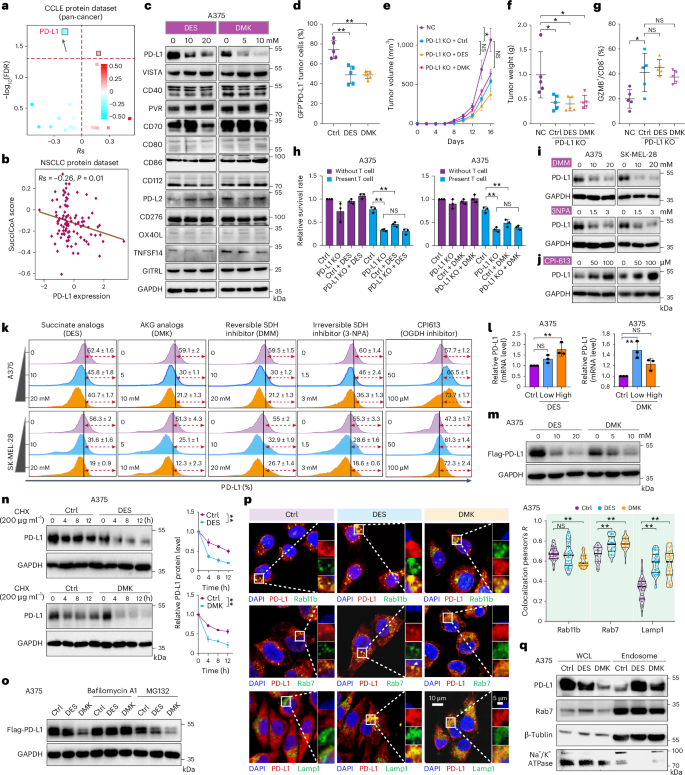

Succinyl-CoA is synthesized through the OGDH-catalyzed decarboxylation of AKG or the reversible conversion of succinate by SCS24,25. Amino acids such as valine, methionine, threonine and isoleucine also serve as precursors. During amino acid metabolism, propionyl-CoA is carboxylated to form d-methylmalonyl-CoA, which is then converted into succinyl-CoA via a vitamin B12-dependent rearrangement25. To explore the relationship between succinyl-CoA and tumor immunity, an index (SucciCoA score; Supplementary Note) was developed to estimate succinyl-CoA content in tumors (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Correlation analysis showed a higher SucciCoA score in nonresponders to immunotherapy (Extended Data Fig. 4b) and poorer survival outcomes in patients with elevated scores (Extended Data Fig. 4c,d). Notably, a negative correlation between PD-L1 levels and succinyl-CoA production was observed in the proteomic data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database (Fig. 2a)26, which was also found in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; Fig. 2b). Treatment with DES and DMK to increase succinyl-CoA levels led to a dose-dependent reduction in PD-L1, with no effect on other immune checkpoints (Fig. 2c). TCA cycle metabolite analogs, including dimethyl fumarate (DMF), triethyl citrate, itaconate and malate, were tested and only DES and DMK reduced PD-L1 protein levels (Extended Data Fig. 5a). In addition, treatment with DES, DMK and DMM lowered PD-L1 in mouse tumor tissues, but increased PD-L1 in OGDH knockdown and glycine-treated mice (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 5b) Similar effects were observed in other cancer types, but no effect was seen in macrophages expressing PD-L1 (Extended Data Fig. 5c,d). To clarify whether DES or DMK modulates PD-L1 via succinyl-CoA, knockdown of ALAS1 (5′-aminolevulinate synthase 1, a rate-limiting enzyme in heme biosynthesis, condensing succinyl-CoA and glycine to form aminolevulinate), which upregulates succinyl-CoA, reduced PD-L1 levels, whereas overexpression of ALAS1 had the opposite effect (Extended Data Fig. 5e,f). Inhibition of glycine transport also led to PD-L1 downregulation, suggesting that increased succinyl-CoA decreases PD-L1 (Extended Data Fig. 5g). Tumorigenesis assays in PD-L1 knockout (KO) mice showed that DES and DMK inhibited tumor growth and enhanced CD8+ T cell activation, with no additional effects in the PD-L1 KO group (Fig. 2e–g and Extended Data Fig. 5h–j). These results suggest that DES and DMK’s anti-tumor effects are mediated by CD8+ T cells, associating with reduced PD-L1 levels. Further experiments with PD-L1 KO showed that DES and DMK did not enhance T cell killing (Fig. 2h and Extended Data Fig. 5k). In addition, SDH inhibitors (3-NPA and DMM) decreased PD-L1 levels, whereas the OGDH inhibitor, CPI-613, increased PD-L1 expression (Fig. 2i–j). Flow cytometry confirmed these results, showing reduced PD-L1 membrane expression after treatment with SDH inhibitors, DES and DMK, whereas CPI-613 elevated PD-L1 levels (Fig. 2k).

a,b, Spearman’s rank correlation between the SucciCoA score and immune checkpoints in the cancer cell lines dataset from the CCLE database (a; n = 375 cell lines) or in the NSCLC protein cohort (b; n = 110 patients). c, Western blot analysis of PD-L1 and other immune checkpoints in A375 cells treated with DES or DMK (n = 3). d, PD-L1 expression in tumor cells quantified by flow cytometry in B16F10 tumor-bearing mice treated with DES or DMK (n = 5 per group). e, Tumor volume measured in mice injected with control or PD-L1 stable KO B16F10 cells, treated with DES or DMK (n = 5 per group). f, Tumor weight measured after euthanasia of mice (n = 5 per group). g, Quantification of GZMB+/CD8+ CTL cells in tumors (n = 5 per group). h, Crystal Violet staining of A375 WT and PD-L1 KO cells co-cultured with activated T cells with or without DES or DMK (n = 3). i,j, Western blot analysis of PD-L1 protein levels in A375 and SK-MEL-28 cells treated with SDH inhibitors (DMM, 3-NPA) (i) or OGDH inhibitor (CPI-613; j) (n = 3). k, Membrane PD-L1 levels after treatment with DES, DMK, DMM, 3-NPA and CPI-613 for 24 h (n = 3). l, The mRNA levels of PD-L1 in A375 cells after treatment with DES or DMK (n = 3). m, Western blot analysis of PD-L1 in A375 cells overexpressing PD-L1, treated with DES or DMK (n = 3). n, PD-L1 protein levels in A375 cells treated with DES or DMK and CHX for various times (in hours) (n = 3) o, PD-L1 overexpression cells treated with DES or DMK, followed by MG132 or pretreated with bafilomycin A1 (n = 3). p, Immunofluorescence showing PD-L1 co-localization with specific marker for recycling endosomes (Rab11), late endosomes (Rab7) and lysosomes (Lamp1) (n = 3). Scale bar, 10 or 5 μm. q, Western blot analysis of PD-L1 in endosomal fractions after treatment with DES or DMK (n = 3). For details on visualization, statistics and reproducibility, see Methods. Note, in d–g, n represents biologically independent samples and, in c, h and q, independent experiments.

Source data

To investigate how these metabolites regulate PD-L1 levels, PD-L1 messenger RNA expression was analyzed after treatment with DES or DMK. Both DES and DMK increased PD-L1 mRNA levels, similar to 3-NPA and DMM, whereas CPI-613 had no significant effect (Fig. 2l and Extended Data Fig. 5l). In stable PD-L1-expression cell lines, DES and DMK treatment led to a more pronounced reduction in PD-L1 protein levels compared with mRNA levels (Fig. 2m). Furthermore, A cycloheximide (CHX) chase assay revealed that DES and DMK treatment shortened the PD-L1 half-life (Fig. 2n). This protein reduction was reversed by bafilomycin A1, a lysosomal degradation inhibitor, but not by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 2o). Similar results were observed in A375 or SK-Mel-28 cell lines with interferon (IFN)γ-induced PD-L1 expression (Extended Data Fig. 5m), suggesting that the succinyl-CoA-mediated PD-L1 reduction primarily occurs at the protein level.

PD-L1 is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and transported to the cell membrane via the Golgi apparatus, where it undergoes either endosomal recycling or lysosomal degradation27,28. It can also be degraded via the autophagy–lysosome pathway29. To examine changes in autophagy after treatment, key markers of autophagy were analyzed. Levels of LC3 I or II were decreased, whereas p62 and beclin1 remained unchanged (Extended Data Fig. 5n). Immunofluorescence analysis showed no increase in PD-L1 co-localization with LC3 (Extended Data Fig. 5o), indicating that PD-L1 degradation induced by these compounds is not autophagy dependent. Immunofluorescence signals for PD-L1 in the ER (GRP94)30, Golgi apparatus (TGN46)31 and circulating endosomes (Rab11)32 showed no notable differences after DES or DMK treatment. However, PD-L1 localization in late endosomes (Rab7)33 and lysosomes (Lamp1)34 was increased (Fig. 2p, Extended Data Fig. 5o and Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition, the isolation of cellular endosomes revealed an increased PD-L1 content in endosomes after DES and DMK treatments, consistent with the fluorescence results (Fig. 2q). These results suggest that elevated intracellular succinyl-CoA promotes PD-L1 degradation via the endosomal–lysosomal pathway.

Succinylation of PD-L1 Lys129 induces its degradation

Succinylation serves as a distinct PTM of proteins. Unlike methylation (14 Da) and acetylation (40 Da), succinylation (100 Da) causes a notable mass shift and alters a positive charge to a negative one, impacting protein function regulation10. Both succinate and AKG elevate succinyl-CoA levels, increasing protein succinylation15,35. Glycine treatment restores PD-L1 protein levels and membrane localization after DES and DMK treatment by reducing succinyl-CoA (Fig. 3a,b). Increased protein succinylation was observed with a pan-antibody recognizing lysine succinylation (Fig. 3c) and immunoprecipitation (IP) assays confirmed PD-L1 succinylation after DES or DMK treatment (Fig. 3d–f and Supplementary Note). This was consistent across other tumor cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 6a). LC–MS identified two succinylation sites on PD-L1, at lysines Lys129 and Lys136 (Fig. 3g and Extended Data Fig. 6b). PD-L1 mutants with Lys129 replaced by arginine showed reduced succinylation (Fig. 3h). Substituting Lys129 with glutamate mimicked succinylation, downregulating PD-L1 levels, whereas Lys129Arg (K129R) had no such effect (Fig. 3i), indicating that DES and DMK primarily target Lys129. The Lys129Glu (K129E) mutation reduced PD-L1’s half-life, whereas Lys129Arg (K129R) prolonged it (Fig. 3j). Mutation of Lys136 lysine sites did not affect PD-L1 stability (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Flow cytometry revealed reduced membrane PD-L1 levels on the membrane in the K129E mutant (Fig. 3k). Tunicamycin treatment inhibited glycosylation (Extended Data Fig. 6d,e) and localization of PD-L1 in the ER and Golgi apparatus did not alter the effect of K129E on PD-L1 (Extended Data Fig. 6f,g), indicating that glycosylation is not involved in the regulation of succinylation on PD-L1.

a,b, PD-L1 levels in A375 cells treated with DES or DMK, and with or without glycine analyzed by western blotting (a) and flow cytometry (b) (n = 3). c, DES or DMK treatment inducing total protein succinylation in A375 cells, detected by pan-succinylated antibodies with PD-L1 as a positive control. d, Endogenous succinylation and PD-L1 detected by western blotting in A375 cells (n = 3). e, Exogenous Flag-tagged PD-L1 (OE) immunoprecipitated and succinylation analyzed by pan-lysine-succinylation antibody (n = 3). f, Succinylation levels of PD-L1 in A375 cells assessed after DES or DMK treatment. g, Statistics of peptides identified to the PD-L1 succinylatable site and the structural pattern of PD-L1. h, Flag-tagged WT and mutant PD-L1 expressed in A375 cells, incubated with succinyl-CoA and analyzed for succinylation (n = 3). i, Western blot analysis of WCL from A375 cells expressing PD-L1 WT, Lys129Arg (K129R) or Lys129Glu (K129E) mutants, treated with DES or DMK (n = 3). j, Western blotting of A375 cells expressing PD-L1 mutants treated with CHX, with quantification of PD-L1 levels (n = 3). k, Membrane PD-L1 levels of mutants measured by flow cytometry (n = 3). l, PD-L1 mutants co-cultured with T cells. Their survival was assessed by Crystal Violet staining (n = 3). m–o, Tumor growth (m), quantification of CD3+/CD8+, GZMB+/CD8+ CTL infiltration (n) and PD-L1 expression (o) evaluated in B16F10 mouse models injected with WT or mutant PD-L1 cells treated with DES or DMK (n = 5 per group). p, Immunofluorescence of PD-L1 co-localization with Rab7 and Lamp1. The co-localization was quantified. Scale bar, 10 or 5 μm. q, Western blot analysis of endosomal fractions from A375 cells transfected with PD-L1 WT or mutants (n = 3). PD-L1, Na+/K+ ATPase and Rab7 levels were detected in endosomes and whole lysates, with β-tubulin as a loading control. r, IP of PD-L1 WT and mutants with HIRP1, CHIP1, Rab11 and Rab7. s, Western blot analysis of A375 WCL expressing PD-L1 WT-UB, K129R-UB or K129E-UB mutants, treated with CHX for different times (n = 3). For details on visualization, statistics and reproducibility, see Methods. Note, in m–o, n represents biologically independent samples and, in the other panels, independent experiments.

Source data

T cell-killing assays were conducted to determine whether DES and DMK affect PD-L1 via succinylation at the Lys129 site. The K129E mutation enhanced T cell killing of tumor cells, whereas PD-L1 wild-type (WT) and K129R mutations inhibited T cell-mediated tumor cell killing. However, DES or DMK treatment substantially enhanced T cell-mediated tumor killing in the PD-L1 WT group, with no notable effects in the K129E or K129R groups (Fig. 3l). In vivo, cells overexpressing either WT or mutant PD-L1, after endogenous PD-L1 KO, showed that PD-L1 WT overexpression promoted tumor growth. Tumors expressing the K129R mutant grew faster than those with PD-L1 WT, whereas the K129E mutant slowed growth. DES or DMK treatment suppressed tumor growth in PD-L1 WT-overexpressing cells, but had little effect in Lys129 mutant groups (Fig. 3m). Both the PD-L1 WT and K129R groups inhibited CD8+ T cell activation, with DES or DMK treatment increasing activated CD8+ T cells in the WT group, but only slightly in the K129R and K129E groups (Fig. 3n). PD-L1 levels in tumors decreased after DES or DMK treatment in the WT group, but not in the mutant groups (Fig. 3o).

To further elucidate the role of Lys129 in PD-L1 lysosomal degradation, immunofluorescence analysis of PD-L1 mutant localization in endosomes showed decreased co-localization of the K129R mutant with Rab7 and increased K129E localization with late endosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 3p). Endosome isolation confirmed these results, with K129R showing reduced endosomal localization and K129E exhibiting increased localization (Fig. 3q). IP revealed increased binding of the K129E mutant to Rab7, but no notable change in binding to other membrane stability proteins, such as CHIP1 and HIRP1 (refs. 28,36) (Fig. 3r).

The endosomal degradation of PD-L1 depends on its monoubiquitination37. To explore the impact of succinylation on PD-L1 monoubiquitination, a ubiquitin molecule was added to PD-L1’s carboxy terminus to mimic its monoubiquitination (UB). The half-life of PD-L1-UB revealed that the K129E mutation shortened its half-life, whereas K129R prolonged it (Fig. 3s). These results suggest that succinylation at Lys129 may influence the endosomal degradation of monoubiquitinated PD-L1, progressing through the endosomal sorting complex required for transport complex-mediated, late degradation phase.

CPT1A mediates the succinylation of PD-L1

MS was employed to identify proteins interacting with PD-L1, revealing its association with the succinyltransferase CPT1A (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b and Supplementary Table 1). Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed the cytoplasmic co-localization of PD-L1 and CPT1A (Fig. 4a). IP analysis further identified interactions between PD-L1 and succinylation-related enzymes, including desuccinylases sirtuin 5 and sirtuin 7 and succinyltransferases KAT2A and P300 (ref. 10), but only CPT1A specifically bound to PD-L1, interacting with its catalytic region (amino acids 123–773) (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 7c–e).

a, Co-localization of PD-L1 with CPT1A detected by immunofluorescence in A375 cells treated with or without DES or DMK. b, IP of CPT1A (top) and PD-L1 (bottom), with western blotting to detect both proteins. c, Western blotting of PD-L1 in CPT1A knockdown or KO A375 cells. d, Inhibition of CPT1A activity using PEM and PD-L1 detection by western blotting. e, PD-L1 protein levels after exogenous CPT1A expression. f, CPT1A knockdown or KO cells co-cultured with T cells for 24 h, followed by Crystal Violet staining (n = 3). g, A375 cells treated with PEM for 24 h, then co-cultured with or without activated T cells for 24 h to assess the killing effect (n = 3). h, CPT1A overexpression cells co-cultured with T cells to assess the killing effect (n = 3). i, Western blotting of PD-L1 after CPT1A, His473Ala (H473A) and Gly710Glu (G710E) mutant overexpression (n = 3). j, CPT1A WT and mutant cells co-cultured with T cells to assess the killing effect (n = 3). k, Western blotting analysis of the effect of CPT1A overexpression on the succinylation of PD-L1 (n = 3). l, Effect of DES or DMK treatment on PD-L1 succinylation and CPT1A expression in endosomes (n = 3). m, CPT1A overexpression cells treated with bafilomycin A1 and glycine, followed by western blotting to detect PD-L1 (n = 3). n, Exogenous expression of CPT1A with PD-L1 WT or Lys129Arg (K129R), followed by western blotting to detect PD-L1 (n = 3). o, Purified CPTA1 and mutants reacting with PD-L1 in succinyl-CoA to detect succinylation of PD-L1 (n = 3). p, Tumor growth in mice injected with B16F10 cells expressing CPT1A WT, H473A or G710E (n = 5 per group). q, Quantification of CD8+/CD3+ and GZMB+/CD8+ CTL cells in tumor masses (n = 5 per group). r, Flow cytometry quantification of PD-L1 in tumor cells (n = 5 per group). s, Immunostaining of CD3, CD8 and GZMB in B16F10 tumors (n = 5 per group). Scale bar, 100 μm. For details on visualization, statistics and reproducibility, see Methods. Note, in p–s, n represents biologically independent samples and, in the other panels, independent experiments.

Source data

Although CPT1A is predominantly located mitochondrially, a recent study suggested potential PD-L1 mitochondrial localization38. Mitochondrial isolation and proteinase K digestion demonstrated a substantial reduction in both PD-L1 and the mitochondrial outer membrane marker TOMM20 (translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20), whereas the intramitochondrial protein COXIV (cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4I1) remained unaffected (Extended Data Fig. 7f). Flow cytometry further confirmed that PD-L1’s extracellular domain is exposed to the cytoplasm and reduced after proteinase K digestion (Extended Data Fig. 7g). IP across various cellular components showed PD-L1 and CPT1A interactions in the cytoplasm (excluding the nucleus), cellular membrane, endosomes and mitochondria (Extended Data Fig. 7h). Immunofluorescence corroborated their localization in mitochondria and endosomes (Extended Data Fig. 7i). Binding of the PD-L1 extracellular fragment (1–238) to CPT1A was confirmed by IP (Extended Data Fig. 7j). Investigation of CPT1A’s relationship with PD-L1 showed that CPT1A knockdown or KO increased PD-L1 expression (Fig. 4c) and treatment with CPT1A inhibitors (perhexiline maleate (PEM) or etomoxir) elevated PD-L1 levels (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 7k). Overexpression of CPT1A reduced PD-L1 levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4e). T cell-killing assays revealed that reduced CPT1A levels or activity impaired T cell-mediated tumor cell killing, whereas overexpression of CPT1A enhanced it (Fig. 4f–h and Extended Data Fig. 7l).

CPT1A WT, the His473Ala (H473A; inactive) mutant, and the Gly710Glu (G710E) mutant (which retains succinyltransferase activity) showed that CPT1A WT and G710E reduced PD-L1 levels, whereas H473A had no effect (Fig. 4i). T cell killing was enhanced in cells with CPT1A WT or G710E, but not H473A (Fig. 4j). CPT1A overexpression also increased PD-L1 succinylation (Fig. 4k) and interaction between CPT1A and PD-L1 was identified in endosomes, further enhanced by DES or DMK treatment (Fig. 4l). PD-L1 levels were rescued with bafilomycin A1 or glycine (Fig. 4m). CPT1A decreased PD-L1 WT levels but had no effect on the K129R mutant (Fig. 4n). In vitro assay showed that CPT1A WT and the G710E increased PD-L1 succinylation, indicating that CPT1A acts as a succinyltransferase for PD-L1 (Fig. 4o and Supplementary Note).

In vivo studies showed that CPT1A knockdown accelerated tumor growth, inhibited CD8+ T cell activation, reduced survival and increased PD-L1 levels (Extended Data Fig. 8a–f), whereas CPT1A overexpression (WT and G710E) inhibited tumor growth and increased CD8+ T cell infiltration and activation (Fig. 4p–q and Extended Data Fig. 8g,h). High CPT1A expression in melanoma is associated with better prognosis and increased activated CD8+ T cells (Extended Data Fig. 8i,j). Overexpression of CPT1A also reduced PD-L1 levels (Fig. 4r) and mIHC confirmed increased CD8+ T cell infiltration and activation (Fig. 4s).

A previous study suggested that CPT1A KO might affect antigen presentation18. Flow cytometry showed that CPT1A WT enhanced antigen presentation, whereas the H473A and G710E mutants had no significant effect (Extended Data Fig. 8k). These results suggest that CPT1A’s regulation of antigen presentation is independent of its succinyltransferase activity.

Induction of CPT1A elevation synergizes with CTLA-4 blockade

CPT1A expression is regulated by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), which upregulates CPT1A in response to its activation39. To explore CPT1A’s potential in immunotherapy, bezafibrate (BEZ), a hypolipidemic agent that acts as a PPAR agonist and activates the PPAR/PGC1α pathway, was utilized40. BEZ increased CPT1A expression in a dose-dependent manner and decreased PD-L1 levels (Fig. 5a). Although no correlation was found between CTLA-4 mAb response and CPT1A or succinylation signatures in previous clinical samples (Extended Data Fig. 8l), combining BEZ with an anti-CTLA-4 mAb inhibited tumor growth reduced tumor size and prolonged survival without affecting body weight (Fig. 5b,c and Extended Data Fig. 8m). Flow cytometry revealed increased GZMB+CD8+ T cells in the combination group (Fig. 5d). Both treatments reduced PD-L1 levels in CD45− tumor cells (Fig. 5e) and mIHC showed enhanced CD8+ T cell infiltration and activation (Fig. 5f). CPT1A knockdown reduced the synergistic effect of BEZ and anti-CTLA-4 mAb on tumor growth and CD8+ T cell infiltration (Fig. 5g–j). Overexpression of PD-L1 WT and K129R mutants attenuated the anti-tumor effects, with K129R exerting a stronger inhibitory effect (Fig. 5k). Although no significant differences were observed in tumor growth or immune suppression, overexpression maintained elevated PD-L1 levels (Fig. 5l–n). These results suggest CPT1A as a promising target for melanoma immunotherapy.

a, Western blot analysis of CPT1A and PD-L1 levels in cells treated with varying doses of BEZ (n = 3). b, Left, tumor growth of B16F10 cells in immunocompetent mice treated with control, BEZ, anti-CTLA-4 or their combination. Right, tumor weights summarized after euthanizing the mice (n = 5 per group). c, Survival of B16F10 tumor-bearing mice after treatments with control, BEZ, anti-CTLA-4 or their combination (n = 5 per group). d, Quantification of CD3+/CD45+, CD8+/CD3+ and GZMB+/CD8+ CTL percentages in tumor masses from different groups (n = 5 per group). e, Flow cytometry quantification of PD-L1 levels in tumor cells (n = 5 per group). f, Immunostaining of CD3, CD8 and GZMB in B16F10 tumor masses post-treatment (n = 5 per group). Scale bar, 100 μm. g,k, Tumor growth of CPT1A KO cells (g) or PD-L1 WT and Lys129Arg (K129R) B16F10 cells (k), along with negative control B16F10 cells, in immunocompetent mice treated with BEZ and anti-CTLA-4. Tumor weights were summarized post-euthanasia (n = 5 per group). h,l, Quantification of CD8+/CD3+ (h) and GZMB+/CD8+ CTL percentages (l) in tumor masses from various groups (n = 5 per group). i,m, Flow cytometry quantification of PD-L1 levels in tumor cells with CPT1A KO cells (i) or PD-L1 WT and Lys129Arg (K129R) B16F10 cells (m), along with negative control B16F10 cells after treatment with BEZ and CTLA-4 (n = 5 per group). j,n, Immunostaining of CD3, CD8 and GZMB in B16F10 tumor masses post-treatment with CPT1A KO cells (j) or PD-L1 WT and K129R B16F10 cells (n), along with negative control B16F10 cells after treatment with BEZ and CTLA-4 (n = 5 per group). Scale bar, 100 μm. For details on visualization, statistics and reproducibility, see Methods. Note: in a, n represents independent experiments and, in the other panels, biologically independent samples.

Source data

CPT1A levels correlate with PD-1 mAb efficacy in melanoma

Only a small subset of patients responds to PD-1 or PD-L1 blockade, because PD-1-mediated immune resistance depends on PD-L1 availability within tumors2,3,4. Our study identified CPT1A as a key mediator of PD-L1 succinylation and degradation. To further investigate the relationship between CPT1A and PD-L1, tumor samples from 45 patients with melanoma treated with anti-PD-1 mAb monotherapy were analyzed (Fig. 6a,b and Supplementary Table 2). A strong negative correlation between CPT1A and PD-L1 expression was observed in tumor resection samples. Notably, nonresponders (NRs) exhibited significantly higher CPT1A and lower PD-L1 levels compared with responders (Rs) (Fig. 6c–e). Consistent with prior studies2,3,4, patients with high PD-L1 expression had a better response to an anti-PD-1 mAb, as shown by longer overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) (Fig. 6f). In addition, patients with lower CPT1A and higher PD-L1 expression had longer PFS (median PFS of 10 months versus 2 months) (Fig. 6g,h). Patients with lower CPT1A and higher PD-L1 showed improved responses to anti-PD-1 mAb therapy (Fig. 6i). A negative correlation was also found between PD-L1 levels and total protein succinylation, with lower protein succinylation levels linked to a better response and prognosis (Extended Data Fig. 9a–e). Collectively, these results suggest that low CPT1A and high PD-L1 expression may predict anti-PD-1 mAb efficacy in melanoma.

a, Summary of the in-house melanoma cohort. b, Heatmap showing the clinical characteristics of the in-house melanoma cohort treated with anti-PD-1 mAb. Each column represents an individual patient. Rs include those with complete response (CR), partial response (PR) or stable disease (SD) > 6 months, whereas NRs include those with SD ≤ 6 months or progressive disease (PD). PFS, 0 means progression free, 1 means progression or death; OS: 0 means alive, 1 means death. c, Representative fluorescence images showing CPT1A and PD-L1 expression in patients with distinct therapy responses. d, Heatmap illustrating a significant negative correlation between CPT1A and PD-L1 expression (Spearman’s rank correlation). e, Box plots showing differential CPT1A and PD-L1 expression between R (n = 26 patients) and NR (n = 19 patients) groups. f, Univariate Cox’s regression analysis of OS (top) and PFS (bottom) based on CPT1A and PD-L1 expression (n = 45 patients). g,h, Kaplan–Meier plots demonstrating the synergistic effects of CPT1A and PD-L1 expression on PFS (g) and OS (h). i, Proportions of patients with different immunotherapy responses in the cohort (n = 45 patients). j, Schematic diagram of summary. The accumulation of succinate or oxoglutarate-derived succinyl-CoA mediates PD-L1 succinylation, serving as an indicator of the intrinsic lysosomal degradation of PD-L1. CPT1A, as a succinyltransferase that controls the succinylation of PD-L1, was identified as a new target for melanoma therapy and may be used in combination with PD-L1 as a marker to predict the effect of anti-PD-1 therapy. For details on visualization, statistics and reproducibility, see Methods. Note, n refers to independent biological replicates. HR, hazard ratio. Schematic in j created using BioRender.com.

Source data

Discussion

The present study identified a correlation across high expression of OGDH, SCS and SDH in melanoma and response to anti-PD-1 mAb immunotherapy. These enzymes reduce succinyl-CoA levels and elevated succinyl-CoA enhances PD-L1 succinylation, promoting its degradation. CPT1A, a succinyltransferase controlling PD-L1 succinylation, was identified as a new therapeutic target and potential biomarker for melanoma for anti-PD-1 mAb efficacy (Fig. 6j and Extended Data Fig. 9f).

Tumor metabolism shapes the tumor microenvironment, but the effects of metabolites on tumors and immune cells remain unclear. Tumors use excessive glucose uptake for glycolysis, producing lactate that inhibits T cell cytotoxicity5,41. Lactate suppresses pyruvate carboxylase and activates pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), reducing succinate secretion, whereas PDH inhibition enables T cells to export succinate, maintaining cytotoxicity via autocrine signaling through SUCNR1 (succinate receptor 1)42.

Despite the Warburg phenotype, melanomas also rely on mitochondrial metabolism for biosynthesis and redox reactions, utilizing intermediates such as citrate and oxaloacetate43. Glutamine is metabolized into AKG, which enters the TCA cycle and is converted by OGDH to succinyl-CoA44,45. Glutamine depletion in tumor cells increases PD-L1 levels, whereas supplementation inhibits melanoma growth46,47. Inhibition of OGDH or glutamine metabolism increased PD-L1 and promoted tumor growth. However, glutamine antagonists have anti-tumor effects48, suggesting that glutamine and AKG influence immune surveillance in ways beyond regulating PD-L1 expression.

Administration of cell-permeable succinate and AKG inhibited tumor growth in mice, an effect heavily dependent on CD8+ T cells. MS showed that DES and DMK treatments increased succinate and AKG levels in plasma and tumors, but not in other organs, indicating tissue-specific metabolic effects. The cell-permeable forms of succinate and AKG rapidly enter cells, influencing both tumor cells and T cells. However, their specific effects on T cells require further investigation. In addition, these findings suggest that succinate may activate T cells through mechanisms other than binding to its receptor, SUCNR1.

The TCA cycle, located in the mitochondrial matrix, encompasses both catabolic and anabolic pathways. In the past decade, nonmetabolic roles for TCA cycle intermediates have been identified49. Succinyl-CoA, derived from the TCA cycle, serves as a primary substrate for succinylation. TCA cycle defects, such as SDH depletion, lead to elevated succinyl-CoA levels and histone hypersuccinylation, which correlates with increased gene expression35. Consistent with these findings, SDH inhibitors (DMM and 3-NPA) also raised succinyl-CoA levels. SDH-mediated conversion of succinate to fumarate inhibits T cell activity in melanoma50. However, treatment with DMF did not affect PD-L1 expression and the increase in intracellular succinate may be more favorable for the formation of succinyl-CoA. Although succinyl-CoA is synthesized in mitochondria, its transport mechanisms to the cytoplasm or nucleus remain unclear, despite evidence of succinylation in these compartments15,51,52,53. Notably, succinate in the cytosol can be converted back to succinyl-CoA11 and OGDH translocated into the nucleus15, possibly explaining cytoplasmic and nuclear succinylation. Further exploration of succinyl-CoA transport will provide insights into cellular metabolism and post-translational modifications. Our data demonstrate PD-L1 succinylation in the cytoplasm. PD-L1 undergoes various PTMs, including phosphorylation, acetylation and palmitoylation, that regulate its function. For example, AMPK-mediated phosphorylation at Ser195 triggers PD-L1 degradation via ER-associated degradation54 and palmitoylation stabilizes its membrane localization37, whereas acetylation of Lys263 facilitates nuclear entry55. Although PD-L1 expression is tightly controlled, the signal for its lysosome degradation remains unknown. Our study identifies succinylation as a signal for PD-L1 degradation in the endosomal cycle. Increased succinyl-CoA production and succinylation in tumor cells correlate with improved prognosis and enhanced immune responses. Short-chain acyl-CoAs, including succinyl-CoA, inhibit CPT1A and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation56,57,58. Recent research highlights succinyl-CoA as a substrate for CPT1A’s lysine succinyltransferase activity16. Our research demonstrated that CPT1A functions as a lysine succinyltransferase for PD-L1, with its inhibition of CPT1A increasing PD-L1 levels. Furthermore, increasing CPT1A via the PGC-1 activator (BEZ) reduced PD-L1 levels and enhanced anti-tumor response to anti-CTLA-4 therapy. BEZ, a clinically safe lipid-lowering agent, may reduce immune-related adverse events compared with combined therapies with anti-CTLA-4. It facilitates T cell activity59 and exerts a more pronounced effect, offering a promising treatment combination option. PGC-1α regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and energy metabolism. Melanoma cells with high PGC-1α and OXPHOS levels show reduced migratory capacity, whereas low PGC-1α expression increases metastatic potential60,61. This heterogeneity in PGC-1α expression may influence PD-L1 levels and immune evasion with low PGC-1α linked to higher PD-L1 and immune escape in melanoma cells.

Reducing CPT1A levels or overexpressing PD-L1 (WT or K129R) impaired the effectiveness of the BEZ and CTLA-4 mAb combination in tumor-bearing mice, highlighting the importance of PD-L1 modification and CPT1A levels in modulating immune activation via PGC-1α. Furthermore, the succinyltransferase activity of CPT1A is essential for tumor growth. Both G710E mutation and WT exhibited similar inhibitory effects on tumor progression, whereas the H473A mutation showed no notable impact. Although CPT1A knockdown promotes tumor growth, previous studies have reported that it reduces major histocompatibility complex-I- or -II-mediated antigen presentation and inhibits T cell-mediated tumor killing53. The overexpression of CPT1A mutants (H473A and G710E), which lack only carnitine palmitoyltransferase activity, also inhibits antigen presentation, suggesting that CPT1A’s succinyltransferase activity is not involved in this process. These findings suggest that CPT1A operates through distinct pathways, emphasizing its potential as a multifaceted target in cancer immunotherapy, influencing both antigen presentation and PD-L1 expression.

In summary, our data underscore the regulatory role of succinylation in PD-L1 stability. Patients’ tumors with low succinylation and CPT1A levels are more likely to respond to immunotherapy. As a key enzyme in fatty acid metabolism, CPT1A inhibition upregulates PD-L1, positioning its inhibitors as potential synergistic agents in immunotherapy. The present study proposes that targeting PD-L1 succinylation with small molecules could enhance the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 or PD-1 therapies.

Methods

Ethical statement

All human and animal studies were conducted in compliance with the relevant ethical guidelines and approved by the appropriate ethics committees. The study protocol (protocol nos. 2022020580 and 202103617) was approved by the institutional review board of Xiangya Hospital and all tissue samples were collected in accordance with the informed consent policy. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study was conducted in compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All animal experiments were approved by the Xiangya Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under protocol no. 2020sydw0466 and all experimental procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Cell culture and treatment

All cell lines used were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Human H460 (NSCLC) and mouse B16F10, B16F10-OVA and MC38 (melanoma and colon cancer) cell lines were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 medium (Biological Industries(BI)) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; BI), penicillin (100 U ml−1) and streptomycin (100 µg ml−1) (Gibco). A375, SK-MEL-28 (human melanoma), HCT-116 (colon cancer) and LLC (mouse lung cancer) cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; BI). All cell lines were routinely tested for Mycoplasma contamination and found to be negative. Compounds were added at specific concentrations and times. MG132 (10 μM) was added 6 h before harvesting the cell. Cells were pretreated with bafilomycin A1 (1 μM) for 2 h, followed by DES (15 mM) and DMK (5 mM). Glycine (100 mM) was added for 6–8 h after 18 h of metabolite analog treatment. For cell treatment to detect PD-L1 or T cell killing, DES (10 mM and 20 mM), DMK (5 mM and 10 mM), 3-NPA (1.5 and 3 mM), DMM (10 and 20 mM) and CPI-613 (50 and 100 μM) were used to treat cells for 24 h. Tunicamycin (2.5 μM) was added at transfection or 24 h after transfection for 24 h. Bitopertin (1–50 μM), hygromycin B (400 μg ml−1) and puromycin (1 μg ml−1) were used for screening of stable cell lines. To detect PD-L1, cells were treated with 1–10 µM PEM or 20–100 µM etomoxir for 24 h. The detection of PD-L1 in melanoma cells was conducted under conditions of IFNγ (10 ng ml−1) induction. Compounds were added to complete medium at the indicated concentrations and times.

Antibodies and chemicals

Anti-PD-L1 (cat. no. 13684), anti-p62 (cat. no. 88588), anti-LC3A/B (cat. no. 12741), anti-Rab7 (cat. no. 95746), anti-PD-L2 (cat. no. 82723), anti-VISTA (cat. no. 54979), anti-Na+/K+-ATPase (v23565), anti-CD40 (cat. no. 40868) and OX40L (cat. no. 14991) were from Cell Signaling Technology. Human anti-PD-L1 (cat. no. ab213524 or ab213480), anti-Granzyme B (cat. no. ab4059), anti-Rab7B (cat. no. ab193360), anti-CD3 (cat. no. ab16669), anti-CD8α (cat. no. ab217344) and anti-Beclin1 (cat. no. ab207612) were from Abcam. Anti-PD-L1 (cat. no. 66248-1-Ig), anti-TGN46 (cat. no. 13573-1-AP), anti-CPT1A (cat. no. 15184-1-AP), anti-Rab11B (cat. no. 15903-1-AP), anti-GRP94 (cat. no. 14700-1-AP), anti-HIP1R (cat. no. 16814-1-AP) and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; cat. no. 60004-1-Ig) were from Proteintech. Anti-CD70 (cat. no. A2032), anti-CD80 (cat. no. A25138), anti-CD86 (cat. no. A1199), anti-CD112 (cat. no. A9622), anti-CD276 (cat. no. A17216), anti-TNFSF14 (cat. no. A2002) and GITRL (cat. no. A7028) were from ABclonal Biotechnology Co., Ltd. CY3 goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. GB21303), FITC goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. GB22303), DAPI (cat. no. G1012) and CY5 goat anti-rabbit IgG were from Servicebio (cat. no. K1034G-Cy5.5). DES (cat. no. W237712), DMK (cat. no. 349631), 3-NPA (cat. no. N5636), DMM (cat. no. 36441), glycine (cat. no. G7126), DMF (cat. no. PHR2118), triethyl citrate (ETC, cat. no. 27500), dimethyl itaconic acid (DMI, cat. no. 592498) and DMA (cat. no. S379239) were from Sigma-Aldrich. MG132 (cat. no. S2619) and bafilomycin A1 (Baf-A1, cat. no. S1413) were from Selleck. BEZ (cat. no. HY-B0637), etomoxir (cat. no. HY-50202), C75 (cat. no. HY-12364), PEM (cat. no. HY-B1334A), bitopertin (cat. no. HY-10809), tunicamycin (cat. no. HY-A0098), hygromycin B (cat. no. HY-K1051) and CPI-613 (cat. no. HY-15453) were from MedChemExpress. In vivo anti-mouse CTLA-4 mAb (cat. no. BE0164) and anti-mouse CD8α mAb (cat. no. BE0061) were purchased from Bio X Cell. For a list of flow cytometry antibodies used in the present study, please see Supplementary Note.

RNA isolation, RT–qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from cultured human cancer cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the standard protocol: 1 µg total RNA was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript III First-Strand cDNA synthesis system (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative (q)PCR was performed using a qPCR system (Eppendorf). All mRNA expression levels were normalized to GAPDH and calculated using the 2−△△CT method. Human PD-L1 primer was as follows: forward, 5′-TATGGTGGTGCCGACTACAA-3′; reverse, 5′-TGCTTGTCCAGATGACTTCG-3′. Human GAPDH primer was as follows: forward, 5′-CATGAGAAGTATGACAACAGCCT-3′; reverse, 5′-AGTCCTTCCACGATACCAA AGT-3′.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in cold radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (Beyotime) in the presence of 1× protease inhibitor cocktail and 1× PhosStop (Roche) after two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The endosome isolation method is described in Supplementary Note. The viscosity of the lysate was removed by sonication and the protein concentration was determined using a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of proteins were loaded on to polyacrylamide gels. Whole-cell extracts were subjected to 10% sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose (NC) membrane, followed by blocking with 5% nonfat milk in PBS and then probed with the indicated primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS–Tween 20, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, cat. no. 111-005-003) or goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, cat. no. 115-005-003). Then, an enhanced chemiluminescence assay was carried out to display specific protein bands.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBS) and then blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA). Slides were incubated with the indicated primary antibodies overnight, followed by incubation with FITC or Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature (RT). The nuclei were stained with DAPI. Tumor samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at RT, then incubated with 3% donkey serum, 1% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30–60 min at RT. Samples were stained with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by FITC and/or Cy3 secondary antibodies at RT for 1 h. Images were visualized using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510).

For patients’ tumor tissues, 4-mm paraffin sections of patient samples were baked for 120 min at 60 °C and then deparaffinized. Antigen retrieval was performed with EDTA buffer, pH 8.0, at a sub-boiling temperature for 8 min, followed by 7 min at a sub-boiling temperature in a microwave oven. After spontaneous fluorescence quenching, the samples were blocked in 3% BSA and PBS with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 1 h at RT. Primary antibody targeting (CPT1A, 1:400; PD-L1, 1:200; succinylation, cat. no. PTM-419 or PTM-410, 1:200) were incubated overnight at 4 °C in the blocking solution and the following day for 30 min at RT. After extensive washing in PBS–0.25% Triton X-100, the secondary antibody, including Alexa Fluor-488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, cat. no. 111-545-003) or Cy3 goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, cat. no. 115-165-003) was added to the blocking solution and incubated for 2 h. DAPI was incubated for 10 min at RT in the dark. Images were detected and captured by fluorescent microscopy (Nikon, ECLIPSE Ts2R). Tumor expression of CPT1A, PD-L1 and succinylation was estimated using the tumor proportion score, representing the percentage of tumor cells with membrane staining62,63.

Plasmids and vectors

Stable transfection cell lines were generated using short hairpin (sh)RNA lentiviral vector (Horizon Discovery Ltd). The targeting sequences were described as follows: CPT1A shRNA human: no. 1: 5′-ACAGTGGTATTTGAAGTTA-3′, no. 2: 5′-TGGACTTCATTCCTGGAAA-3′ and no. 3: 5′-ACGATGTACGCCAAGATCG-3′; and mouse: no. 1: 5′-GGCAGAAAATTGTTCTTAT-3′ and no. 2: 5′-AGAGACAACTGTAAGTCAA-3′.

OGDH shRNA pool (mouse) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (cat. no. sc-60106-SH). CPT1A (hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged) and PD-L1 (Flag-tagged) plasmids were purchased from Sino Biological, Inc. CPT1A WT, mutant and truncation constructs were generated using pEGFP-C2 vectors. Plasmids for stable expression were created using pCDH-MCS-Puro-GFP. HA-tagged PD-L1 and its fragments were constructed using pcDNA3.1-CHA. Hygromycin B selection marker vectors were produced using pCDH-MCS-HyB-GFP and ALAS1 (Flag tagged) was also made using pCMV-tag2b. The PD-L1-UB plasmid was ligated between the PD-L1 sequence and the UBB sequence using the T2A sequence, constructed by VectorBuilder Inc. Specific mutations were constructed using Mut Express II Rapid Mutagenesis Kit V2 (Nanjing Woenzyme Biotechnology Co., Ltd).

Using pLentiCRISPR v.2 to generate CPT1A or PD-L1 KO or knockdown cells the targeting sequences are as follows: CPT1A single guide (sg)RNA no. 1: 5′-CACCGTAGCTGTCCAT TGACGTATC-3′; no. 2: 5′-CACCGAGCTGTCCATTGACGTATCC-3′; PD-L1 sgRNA, human: 5′-ACCGTTCAGCAAATGCCAGT-3′; and mouse: 5′-TATGGCAGCAACGTCACGA-3′.

To package lentivirus, the expression or LentiCRISPR KO constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells with two packaging plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G). The medium was changed at 16 h after transfection. The supernatant was collected at 24 and 48 h after transfection. A375 and SK-MEL-28 cells (60% confluency) were incubated in lentivirus-containing medium with polybrene (10 μg ml−1; Selleck Chemicals). Cells were selected by puromycin after 48 h of infection (1 μg ml−1; Selleck Chemicals).

Mouse model and in vivo experimental therapy

All in vivo experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Changsha, Hunan, China). WT malignant tumor cells, including B16F10 (5 × 105), B16F10-OVA (5 × 105), LLC (1 × 106) and MC38 (1 × 106), were subcutaneously injected into 6-week-old C57BL/6 female mice (from the Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Center). After 1 week, mice were pooled and randomly divided into several groups. The groups were treated daily with DES and DMK (500 mg kg−1, intraperitoneally (i.p.)), DMM (200 mg kg−1, i.p.) or vehicle control. To deplete CD8+ T cells, anti-mouse CD8α mAb (Bio X Cell) was administered to metabolite-treated, B16F10 tumor-bearing mice. PD-L1 KO B16F10 cells (5 × 105) were also injected into mice and a negative control group, followed by treatment with DES or DMK and their respective vehicles. To deplete macrophages in C57BL/6 mice, clodronate-loaded liposomes (FormuMax Scientific, Inc.) were administered via injection. An initial intraperitoneal dose of 200 μl of clodronate liposomes was administered 48 h before injection of 5 × 105 B16F10 melanoma cells, followed by subsequent 100-μl doses at 5-d intervals. For constructing stable overexpressed cell lines, PD-L1 WT and mutants (Lys129Arg: K129R or Lys129Glu: K129E), CPT1A WT and mutants (His473Ala: H473A or Gly710Glu: G710E) were transfected into B16F10 cells, vector selected with puromycin and then injected into mice to evaluate the effect. In combination therapy experiments, BEZ was administered at 15 mg kg−1 daily and CTLA-4 mAb at 200 µg per mouse in 100 μl of Dulbecco’s PBS buffer every 3 d via intraperitoneal injection. Furthermore, CPT1A KO or PD-L1 overexpression and their negative control cells were also cotreated to test whether BEZ promotes the efficacy of CTLA-4 mAb therapy through the CPT1A–PD-L1 axis. OGDH KO cells were also generated and injected into mice to evaluate the role of succinyl-CoA production in tumor immunity. Tumor growth was monitored and tumors collected for flow cytometry (FACS) analysis. Xenograft tumors were also snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Paraffin-embedded tumor blocks were prepared for further analysis.

Clinical data and sample collection

Paraffin sections of tumor tissue from 45 patients with melanoma were treated with anti-PD-1 mAb at Xiangya Hospital between March 2018 and January 2022. All patients were followed for >6 months. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Xiangya Hospital. All tissue samples were collected with written informed consent from all the patients. Clinical information has been summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Patients were stratified into response groups based on RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) 1.1 criteria; patients with a complete response (CR), partial response (PR) or stable disease (SD) with PFS > 6 months were classified as Rs, whereas patients with SD and PFS ≤6 months and PD were categorized as NRs64.

Pathway enrichment analysis and GSVA

We used the Estimate (v.1.0.13) algorithms65 to assess the total immune infiltration level. The infiltration level of immune cell populations was calculated by performing gene set variation analysis (GSVA, v.1.40.1)66. The gene signature of activated CD8+ T cells was downloaded from Charoentong et al.67. The gene sets ‘h.all.v6.1.symbols’ and ‘c2.cp.kegg.v6.2’ were retrieved from the MSigDB database (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp)68. Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the fgsea (v.1.18.0) package69 and the clusterProfiler (v.4.0.5) package70.

Spatial transcriptome analysis of melanoma datasets

Spatial transcriptome data were qualitatively controlled using parameters including total spots, median unique molecular identifiers per spot, median genes per spot and median mitochondrial genes or spots. Normalization across spots was performed with the log(variance to mean ratio) function and spatial feature expression plots were generated with the SpatialFeaturePlot function in Seurat (v.4.4.0)71. The signature score derived from the single-cell RNA sequencing dataset (Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) accession no. GSE189889 (ref. 72); Supplementary Note) was added to ‘metadata’ of the ST dataset by calculating the mean expression levels of each gene. The Mal, Bdy and nMal regions of ST slides were determined by the BoundaryDefine function in the Cottrazm (v.0.1.1) package73. The cellular composition of each spot was calculated by the SpatialDecon function and pie plots of deconvolution were generated using the DeconPieplot function in the Cottrazm (v.0.1.1) package. The OGDH/SCS/SDH complex level of each spot was calculated and then the OGDH/SCS/SDH complex level was compared across different locations (Mal, Bdy and nMal) using Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test.

Visualization, statistics and reproducibility

All quantitative data are presented as the mean values ± s.d. of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance: two-sided, unpaired Student’s t-tests were used in Figs. 1h, 4h and 5g–j and Extended Data Figs. 1j, 2c–e,g, 3j,l–n,p and 5b; one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test was used in Figs. 1f,i–k,n,p, 2d–h,l,n,p, 3j,l–p,s, 4a,f–h,j,p–s and 5b–f,k–n and Extended Data Figs. 1c–h,k–m, 2a,b,d,h,i, 3d–i, 5d,i,j,l,o, 7l and 8b,c,e,f,h,k–m; two-sided Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test was used in Figs. 1l and 6e and Extended Data Figs. 3c, 4b, 8j,l and 9b,d,e; two-sided Spearman’s correlation analysis was used in Figs. 2a,b and 6d and Extended Data Fig. 1b with false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons; a log-rank test was used in Figs. 1e,g, 5c and 6g,h and Extended Data Figs. 2f, 3o, 4c,d and 8d,i; the two-sided χ2 test was used in Fig. 1d; and two-sided Fisher’s exact test in Fig. 6i. For Extended Data Fig. 1a, pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the normalized enrichment score to assess the enrichment of predefined gene sets. Statistical significance was evaluated using two-sided P values, with FDR correction for multiple comparisons. P values are indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, NS (not significant, P > 0.05). For Figs. 1c–e and 6f–h and Extended Data Figs. 4c,d, 8i and 9c, survival analysis was performed using the survival (v.3.5.7) R package. The hazard ratio (HR) was calculated using Cox’s proportional hazards model, the 95% confidence interval (CI) reported and the Kaplan–Meier survival curve modeled by survfit function. In data represented as box plots (Fig. 6e and Extended Data Figs. 8j,l and 9b,d,e), the middle line corresponds to the median, the lower and upper hinges describe the first and third quartiles, the upper whisker extends from the hinge to the largest value no further than 1.5× the interquartile range (IQR) from the hinge and the lower whisker extends from the hinge to the smallest value, at most 1.5× the IQR of the hinge. Data beyond the end of the whiskers are outlying points that are plotted individually. In data represented as violin plots (Figs. 1l, 2p, 3p and 4a and Extended Data Figs. 3c, 4b and 5o), the middle line corresponds to the median, whereas the width of the plot at different values represents the data density, with wider sections indicating higher density and narrower sections lower density. The lower and upper hinges represent the first and third quartiles, respectively. The range between the quartiles shows the IQR and outliers are plotted individually as points outside the whiskers, which extend from the hinges to the furthest data points within 1.5× the IQR. In data represented as a Forest plot (Figs. 1a and 6f), a univariate Cox’s regression model was used to calculate the HR: each square represents the HR for a particular gene or pathway, with the size of the square corresponding to the weight of the analysis. The horizontal line extending from each square indicates the 95% CI of the HR, representing the range of values within which the true HR is expected to lie with 95% confidence. A vertical dashed line at HR = 1 is used as the reference point, with HRs to the left of this line indicating a reduced risk of the event and HRs to the right indicating an increased risk. The Immunofluorescence image are representative of experiments (Figs. 1j, 2p, 3p, 4a,s, 5f,j,n and 6c and Extended Data Figs. 5o, 6f,g, 7i and 9a). Several figures contain panels created using BioRender. Overall, no statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment. Bioinformatic data were analyzed and visualized using R (v.4.1.0) software. Experimental data were analyzed and visualized using GraphPad Prism (v.8.0.1) software.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses