An automatic pipeline for temporal monitoring of radiotherapy-induced toxicities in head and neck cancer patients

Introduction

Head and neck cancer management presents a challenge characterized by its intricate anatomical location and diverse etiological factors. Radiotherapy is a pivotal component in the treatment of head and neck cancer, offering the potential for disease control while preserving vital functions. However, radiotherapy may give rise to a spectrum of short-term and long-term toxicities1. Short-term toxicities such as mucositis and dermatitis often appear during the course of the treatment2. In contrast, long-term toxicities such as xerostomia and dysphagia can manifest after the completion of the treatment3. Such toxicities cause chronic discomfort and functional impairments and reduce the overall quality of life of the patients4,5. Understanding the timing of various toxicities is important for personalized radiotherapy treatments6. This understanding enables healthcare providers to anticipate when these toxicities might occur, allowing them to proactively offer support and interventions to manage side effects as needed.

Despite the importance of toxicity monitoring for patient management, most electronic health record (EHR) systems do not document these side effects as structured data; instead, toxicities are often reported as unstructured textual data within clinical notes. Manual review of clinical reports is labor-intensive and error-prone, making it particularly difficult to have a temporal analysis of toxicities, underscoring the need for automatic extraction. Natural Language Processing (NLP) addresses these challenges by automating the extraction process, enabling efficient temporal analysis7. NLP models can identify and extract information such as patient demographics, medical conditions, treatments, and outcomes from unstructured clinical text8,9. Among these models, pre-trained language models (PLMs) have significantly advanced NLP by providing a robust framework for understanding and generating human language10.

The general understanding of the scope, time of onset, and duration of radiotherapy-induced toxicities is well-documented in the medical literature. However, the primary contribution of our work lies in the development of an automatic system capable of extracting, monitoring, and analyzing these toxicities over time using clinical reports. Pre-trained language models such as BERT10, Clinical BioBERT11, and Clinical Longformer12 were fine-tuned on a large set of annotated clinical reports to automate the tasks of toxicity classification and extraction. By reducing the burden of manual assessment of toxicities and providing clinicians with precise information, our approach has the potential to enhance treatment outcomes for patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. This allows not only to facilitate prospective studies13 but also to glean information retrospectively.

Results

Performance of classification models

Table 1 reports the performances of different models for Tasks 1 and 2. The models are primarily compared with respect to the F1 score since it is an aggregate of precision and recall. Clinical Longformer consistently outperformed BERT and Clinical BioBERT across both Tasks, with F1 = 0.93 on Task 1, and overlapping F1 = 0.90 and strict F1 = 0.82 on Task 2. In Task 1, the 0.05 difference between the F1 scores of Clinical Longformer and BERT corresponds to approximately 33 reports. While the differences in Task 1 were not pronounced, Task 2 showed more sizeable differences.

Incidence and persistence of toxicities

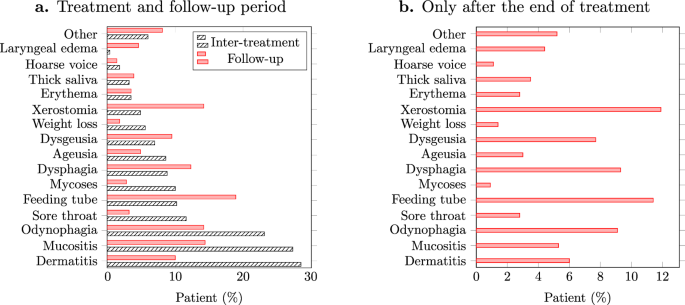

Comparing the incidence of toxicities before and after treatment can help evaluate the efficacy of interventions aimed at reducing treatment-related toxicities, guiding future treatment protocols. Figure 1a shows the fraction of patients with different toxicities during and after the treatment. Most of the toxicities demonstrated considerable differences in their incidence during and after treatment, among which the differences for dermatitis, mucositis, xerostomia, and laryngeal edema were more pronounced. It should be noted that the majority of the patients had similar follow-up schedules.

a Fraction of patients experiencing various toxicities during the treatment and follow-up periods, b Fraction of patients whose toxicities appeared only after the end of treatment.

Toxicities were also compared with respect to the late onset of side effects. Figure 1b illustrates the fraction of patients whose toxicities have appeared for the first time during the follow-up period. Among the toxicities, xerostomia, dysphagia, and odynophagia show significant incidence.

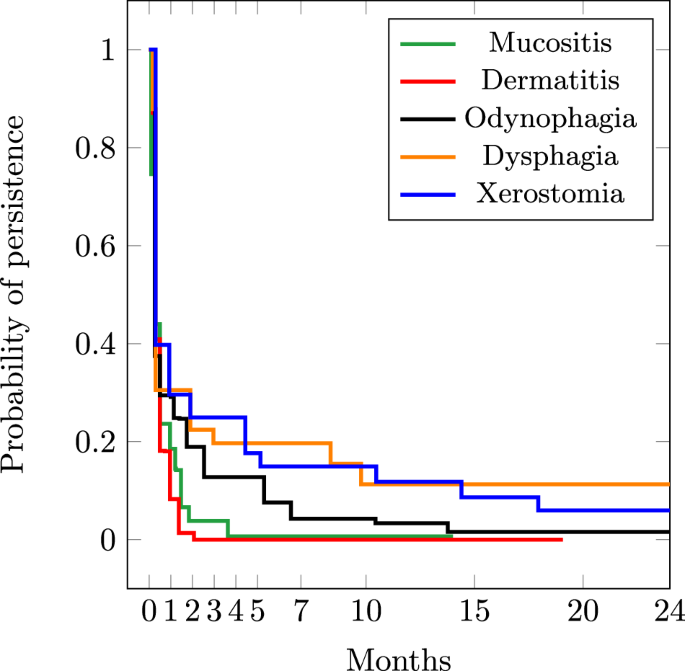

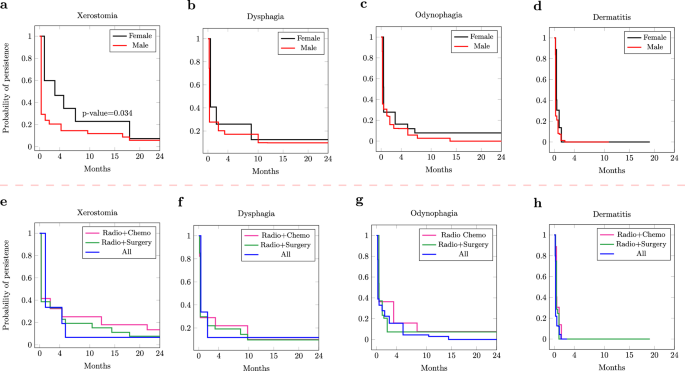

Figure 2 presents the estimated persistence probabilities of the top five frequent toxicities obtained by Turnbull’s algorithm14. Note that the event was defined as the resolution/end of a toxicity. The persistence of toxicities was also compared among different sex and treatment groups as presented in Fig. 3. This can provide insights into the effectiveness of different treatments in managing or reducing the severity of toxicities, as well as revealing potential sex-specific differences in toxicity outcomes, guiding the development of sex-specific treatment strategies.

Probability of persistence for top-5 frequent toxicities.

a The difference in the persistence of xerostomia between males and females is significant. b–d The differences in the persistence of dysphagia, odynophagia, and dermatitis between males and females are not significant. e–h The differences in the persistence of dysphagia, odynophagia, and dermatitis between different treatment modalities are not significant.

Discussion

A higher performance of Clinical Longformer compared to BERT and Clinical BioBERT was expected since Longformers can process longer inputs (long reports). Note that, in Task 1, a single toxicity mention was enough to classify a report correctly, even if all other mentions were truncated. This is due to the limited input size of BERT and Clinical BioBERT. For Task 2, however, truncated input substantially impacted the model’s performance. Moreover, since Clinical BioBERT was exposed to clinical reports during its pre-training process, it performed better than BERT.

For Task 1, Clinical Longformer demonstrated a high recall. A high recall ensures that the system does not miss toxicity-related documents for an automatic monitoring pipeline. Out of 159 positive test reports containing at least one toxicity mention, a recall R=0.97 corresponds to 4.7 missed positive reports. Clinical Longformer also demonstrates a high precision, where the precision of P=0.90 corresponds to 16 reports incorrectly classified as positive.

On Task 2, Clinical Longformer provides a balance between precision and recall. This ensures that the identified toxicities are not only relevant and accurate (high precision) but also comprehensive, capturing a significant portion of all toxicities mentions in the text (high recall). This completeness and accuracy lead to a more reliable representation of toxicities, minimizing both false positives and false negatives. This coverage is important for obtaining a complete picture of the temporal patterns of toxicities, which is essential for understanding their development, persistence, and resolution over time.

Acute toxicities represent the immediate or early onset of adverse effects following radiation exposure, typically within days to a few weeks of treatment initiation. As illustrated in Fig. 1.a, while weight loss is more frequent during the treatment, it seems to be controlled after the treatment. Interestingly, as weight loss is less frequent in the follow-up period, the use of feeding tubes increases. This may suggest that most patients have benefited from PEG feeding15 as a measure to control acute weight loss. As acute toxicity, ageusia (loss of taste) was also more frequent during the treatment period, which can be due to the direct impact of radiation on taste buds. This can overwhelm the taste buds’ ability to function16.

The incidence of sore throat before and after showed a pattern similar to mucositis. The mucous membranes in the throat are particularly sensitive to radiation, leading to inflammation and irritation, causing sore throat17. The significant difference between the incidence of xerostomia during and after the treatment could be attributed to the cumulative effect of radiation on salivary glands18. Salivary glands can still produce saliva during radiotherapy19, although the production might be reduced. However, the full impact of radiation on the glands may not be immediately apparent. The stark difference between the incidence of mycoses during and after the treatment could result from a compromised immune system due to the cytotoxic effects of radiation on healthy tissues, which creates a favorable environment for the development of fungal infections such as mycoses. However, after the end of radiotherapy, the immune system may gradually recover, which reduces the susceptibility to fungal infections and, therefore, less incidence of mycoses during the follow-up period.

As Fig. 1.b illustrates, xerostomia, dysphagia, and odynophagia were among the most frequent toxicities that appeared after the end of treatment. This suggests that the effect of radiotherapy has been cumulative, meaning that the damage to tissues continues to develop and evolve even after treatment has ended, leading to the late onset of symptoms20. Note that the frequency of using a feeding tube is also consistent with the presence of symptoms such as dysphagia and odynophagia.

Laryngeal edema was rarely observed during the treatment (see Fig. 1.b), but it demonstrated more occurrence post-treatment, suggesting that inflammation and tissue swelling may develop as a delayed response to the accumulated radiation dose. The automatic monitoring of toxicities such as laryngeal edema can also help to identify patients with the risk of recurrence21,22. Dysgeusia also had a late onset, which might have two potential reasons. First, the damage to taste buds might occur gradually over the course of treatment, and it may take some time for the effects to manifest fully. Second, dysgeusia might appear late, after the resolution of loss of taste. Particularly, the regeneration potential of taste buds might influence the observed timeline23. Dysgeusia may occur as taste buds regenerate and as the underlying cause of the temporary loss of taste resolves. Further investigation revealed that 30% of the patients who experienced ageusia during the treatment later experienced dysgeusia in the follow-up period as late toxicity.

The automatic extraction of toxicity mentions enables capturing cases like the transition of auguesia into dysgeusia post-treatment, and provides insights into the dynamic nature of these toxicities. This also helps to understand the progression of toxicities and their potential long-term effects and as well as monitoring the effectiveness of interventions to manage toxicities. In general, automatically monitoring these toxicities can help with early detection and management. This proactive approach allows for identifying high-risk patients who require closer monitoring by adjusting treatment plans (e.g. dose fractionation) or providing supportive care to mitigate the impact of late-onset symptoms4,24.

Here, we showcased the potential utility of the automatic extraction of toxicity by focusing on a subset of toxicities. Oncologists and medical practitioners can leverage this pipeline to analyze a wider range of toxicities beyond those discussed in this paper. The flexibility of the pipeline allows users to select and prioritize the toxicities they wish to analyze, tailoring the analysis to their specific clinical or research needs.

The probabilities of persistence for both dermatitis and mucositis (Fig. 2) dropped significantly after one month, suggesting that for the study cohort, these toxicities are often resolved within a relatively short period after treatment completion2. This aligns with clinical observations where patients commonly experience a gradual improvement in these side effects as they recover from the acute phase of treatment. However, toxicities such as xerostomia and dysphagia maintain considerable persistence probabilities, even after seven months. This prolonged persistence aligns with the known nature of these toxicities, resulting from the cumulative effects of radiotherapy on salivary glands and swallowing muscles. The persistence of these toxicities underscores the importance of long-term monitoring and supportive care for cancer survivors, as these side effects can significantly impact quality of life and require ongoing management strategies. For odynophagia, the probability of persistence approaches zero after 14 months, suggesting that the mucosal lining has had sufficient time to heal and regenerate, leading to the resolution of the symptoms. This duration of persistence is in line with observations made by other studies such as13.

The comparison of persistence among different groups (Fig. 3) suggests that females show a significant probability of persistence for xerostomia compared to males. The asymptotic log-rank test resulted in a p-value=0.034 < 0.005, showing that the difference between the probabilities of persistence of xerostomia between males and females is statistically significant. This might be due to fluctuations in hormone levels, particularly estrogen, which can affect salivary gland function25. In fact, menopausal females often experience decreased estrogen levels, which can lead to changes in saliva production and composition. This hormonal shift can exacerbate xerostomia and contribute to its persistence26. While males and females show some differences in the persistence of dysphagia and odynophagia (Fig. 3.b,.c), there is almost no difference in the persistence of Dermatitis for the two groups (Fig. 3.d). This may suggest that both males and females may have received comparable management strategies for dermatitis. Moreover, males and females may have similar skin biology, and it is plausible that both groups would exhibit similar rates of dermatitis persistence. As Fig. 3.e suggests, patients who had surgery (Radio+Surgery/All) show a lower probability of persistence for xerostomia. Note that 24% of surgeries involved a salivary gland transfer before radiotherapy, which might explain the reduced effect of xerostomia. For both dysphagia and odynophagia, when all treatment modalities are combined, a lower probability of persistence is observed, albeit not significantly. Finally, similar to the sex groups, treatment groups show no differences in the duration of dermatitis.

Although the scope, timing, and duration of radiotherapy-induced toxicities are well-documented in the medical literature, we included these insights to show that the information extracted by our pipeline aligns with established clinical observations. This alignment not only validates the correctness and reliability of our system but also ensures that it captures clinically relevant patterns, bolstering its utility for real-world applications.

Large language models (LLMs) have gained widespread popularity due to their impressive performance across various tasks such as text generation, translation, and summarization. Currently, the most common way of using LLMs is through prompting, which is a description of the task together with some input text to be processed. However, LLMs can produce inconsistent results when prompted27, as their outputs can vary significantly based on the phrasing of the prompt. In Supplementary materials, we show how the state-of-the-art Lama 3.1 70b28 leads to inconsistent normalization of toxicities to their UMLS concepts. This variability introduces a level of unpredictability that is unacceptable in clinical settings, where precision is crucial. Prompting also gives less control over how the model generates its output, making it harder to ensure that the extracted information, in our case toxicities, is captured with the required detail and specificity. We also conducted an additional experiment with the domain-specific model llama3-openbiollm-8b, which is fine-tuned for biomedical tasks (provided as supplementary information). Despite its specialization, this model also struggled to code toxicities in our dataset correctly. The problem of assigning wrong codes could potentially be mitigated through independent mechanisms. One potential solution could involve integrating UMLS MetaMap29 as a post-processing step to ensure accurate mapping to UMLS codes. Another promising approach is the use of Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)30, which would allow LLMs to query the complete UMLS terminology during inference, potentially improving their ability to handle domain-specific terms. While these methods show promise, they also introduce additional complexity and computational overhead, which may not align with the practical requirements of clinical deployment in their current form.

In contrast to the prompting approach, fine-tuning language models (applicable to both large- and medium-sized models) often provide more stable, consistent outputs critical for extracting sensitive medical information. With fine-tuning, users can optimize the model to prioritize certain information and adapt it to the specific characteristics of their dataset, ensuring the extracted information aligns with their objectives. Large models, while powerful, can be difficult to fine-tune effectively for specific tasks. Their size and complexity often require substantial computational resources and very large datasets to adapt them for a particular use case. In contrast, moderate-sized models like Clinical Longformer and BioBERT are more manageable and can be fine-tuned with relatively less computational power and smaller, domain-specific data sets. This makes them highly adaptable to specific tasks such as toxicity extraction and normalization, allowing for efficient and targeted fine-tuning without the need for the extensive infrastructure that larger models demand.

Many studies suggest quantization techniques to alleviate the need for extensive computational resources of large language models, which reduce the precision of model weights from 32-bit floating point to lower-bit representations. While quantization reduces the memory and computational requirements of large models31, LLMs still retain their inherent complexity. Fine-tuning these models, even in a quantized state, often requires advanced expertise in model optimization, the use of methods such as parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT), and significant computational infrastructure to achieve optimal results32. In comparison, moderate-sized models like BioBERT are specifically pre-trained for biomedical tasks and can be fine-tuned with less effort and more stability, even by users with less specialized expertise, like medical practitioners. Moreover, the use of moderate-sized language models like Clinical Longformer and BioBERT aligns with Occam’s Razor, as they offer a simpler, more efficient solution that achieves high performance without the unnecessary complexity of larger models.

While some of the aforementioned problems including the computational demand might be addressed by utilizing LLMs through Application Programming Interfaces (APIs)33, using large models through external APIs raises privacy concerns. Transmitting sensitive patient data to external servers can compromise data security and violate regulations like Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)34. On the other hand, moderate-sized models like Longformer and BioBERT can be easily deployed on local servers, ensuring better compliance with privacy standards while maintaining high performance for clinical tasks. Their balance between fine-tunability and resource efficiency makes them a more practical choice for extracting toxicities from clinical data.

Compared to published studies for automatic extraction of radiotherapy-induced toxicities, this study has several advantages. First, by extracting and normalizing the spans of toxicities, our study provides more granular and detailed information about the nature of toxicities. This level of detail is crucial for understanding the impact of radiotherapy and for tailoring treatment strategies to individual patients, ultimately leading to more personalized and effective care. Studies such as ref. 35 only try to address binary classification of reports mentioning toxicities (similar to our Task 1). Moreover, the temporal analysis adds another layer of depth to understanding toxicity patterns over time. This temporal aspect is vital for identifying trends, predicting future toxicities, and optimizing treatment schedules to minimize side effects. Finally, our dataset is substantially larger, comprising 1986 more reports of various anatomical subsites, compared to the total 1524 reports used by Chen et al.35. This provides a richer source of information and leads to a more robust and generalizable NLP model.

Compared to other studies, such as the prospective study by Barnhart et al.13, where the temporal behavior of toxicities for head and neck cancer patients were investigated, our study has two major advantages. First, the larger sample size of 384 patients provides a more representative dataset compared to the population of ref. 13 (96 patients). Second, the longer 7-year duration of our study can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the long-term effects of radiotherapy-induced toxicities, compared to the shorter 3-year duration of the study by Barnhart et al.13, which allows for a more thorough investigation of the temporal patterns and persistence of toxicities over time.

Future work will focus on modeling the time-to-event estimations for the appearance of toxicity rather than their persistence, which was investigated in this study. The time-to-event estimates can then be correlated with the delivered dose. Additionally, the generalization of the NLP models to other cancer types needs to be evaluated to assess their robustness and applicability beyond head and neck cancer patients. An interactive visualization tool can also be developed to allow clinicians to easily investigate the extracted toxicities and their temporal patterns, facilitating better understanding and interpretation of the NLP models. Moreover, we plan to study strategies to optimize the integration of LLMs with RAG, aiming to reduce computational demands significantly. This would involve low-resource inference mechanisms and scalable architectures that can run on standard clinical IT infrastructure without requiring extensive computational resources.

Our study showcased the benefits of automatically extracting radiotherapy-induced toxicities from clinical reports, enabling temporal analysis focused on persistence and early or late onset. Though specific toxicities were examined, the approach is flexible, allowing clinicians to choose which toxicities to analyze. This adaptability supports personalized cancer care and tailored treatment strategies. The developed NLP system has several advantages for integration into EHR systems. It accurately extracts and normalizes toxicity mentions, offering a standardized representation of clinical data. This allows for continuous monitoring of clinical reports to track toxicity persistence, helping clinicians plan treatments by anticipating and managing side effects. We also showed that moderate-sized language models such as Clinical Longformer and bioBERT remain viable backbones for this task, providing efficient processing without the need for extensive computational resources, making them suitable for deployment in clinical settings. An automatic pipeline for temporal monitoring supports the analysis of toxicities among subgroups and provides a center-specific view. This enables healthcare providers to compare their data with broader benchmarks, which can guide improvements in patient care and treatment protocols.

Methods

Patient population and data

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board (REB) of Hôpital Général Juif (HGJ), Montreal, Canada (approval number MP-05-2022-2469). The study utilized de-identified, retrospective clinical data collected during routine care, with no direct contact with patients or interventions altering their treatment. Informed consent was waived because the research presented minimal risk to participants, did not adversely affect their rights or welfare, and obtaining consent was impracticable due to the nature of the study involving historical data. The cohort for this study consists of 384 patients with head and neck cancer who underwent radiotherapy, either as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy or surgery, at the JGH, between 2013 and 2020. On average, the patients received 48.2 Gy in 28.7 fractions. Table 2 provides a summary of the cohort characteristics. Our cohort comprises different anatomical subsites. This diversity presents a key advantage, as it allows for the learning of toxicity patterns across different subsites. Given that each subsite may have unique toxicity profiles and treatment-related effects, the inclusion of multiple subsites enhances the model’s robustness and generalizability.

We focused on two types of notes, namely inter-treatment and follow-up notes. Inter-treatment notes are concise summaries documenting the patient’s progress and response to the treatment regimen, including toxicities during the course of the radiotherapy treatment. Overall, 1228 inter-treatment notes were extracted from the EHR system. On average, 2.8 reports were available for each patient. The maximum number of inter-treatment notes for patients was 7. Follow-up notes documented the patient’s progress and any lingering or emerging toxicities beyond the treatment period, indicating the transition from short-term to long-term effects. With a total number of 2282 follow-up notes, on average, each patient had 5.3 notes, and the maximum number of notes for patients was 21.

Template-specific sections such as headers and footers were removed as a pre-processing step. Removing such sections allows the dataset to focus on the narrative text of the clinical reports. Moreover, most of the patient’s personal information is recorded in such sections. All notes were de-identified to comply with REB mandates. This includes redacting all personal information such as name, patient ID, date of birth, case number, and references to hospital personnel or referring physicians.

Annotation process

Annotating toxicities

The first step of the annotation process involved a pre-annotation procedure, where all reports were matched against the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) terminology36. This process focused on terms classified under the semantic types of Disease or Syndrome, Finding, and Symptom. By referencing these established terminologies, the annotation workload is significantly reduced. A careful manual review of the reports was then conducted to remove false annotations, add missing annotations, or extend existing annotations. To ensure the accuracy and clinical relevance of the annotations, the annotation process was conducted in close collaboration with the radiation oncologist who has treated the patients. In addition to radiotherapy, a subset of patients in the cohort have received chemotherapy and/or surgery. Thus, during the annotation process, after consultation with the treating radiation oncologist, mentions of toxicities, such as nausea or fatigue, that could be attributed to chemotherapy or surgery were excluded unless there was a clear and explicit indication that the cause was radiotherapy. This ensures that the annotations accurately reflect the toxicities related to radiotherapy. Moreover, if a mention of pain did not explicitly refer to a site (mouth, throat, etc.), it was excluded. By excluding such mentions, the annotation guidelines help maintain consistency and relevance, ensuring that the extracted data aligns closely with the study’s objectives. The use of feeding tubes was annotated as a special category of toxicity since it is often evidence of dysphagia or ageusia. Overall, more than 1600 mentions of different toxicities were annotated.

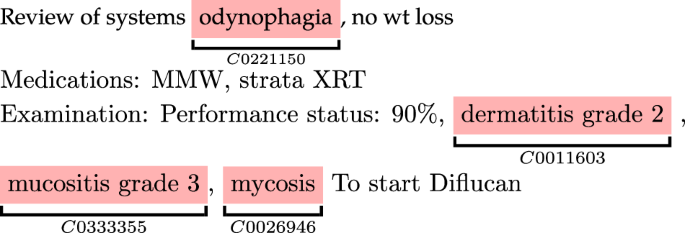

Assigning concept codes

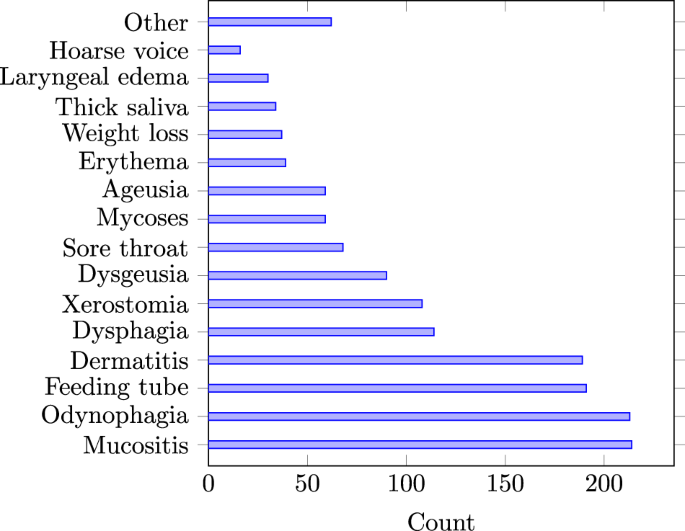

In clinical reports, the same type of toxicities are often mentioned using different terms. Examples are synonym terms such as xerostomia and mouth dryness that refer to the same concept. These mentions needed to be mapped (normalized) to the same code using the UMLS Concept Unique Identifier (CUI)36, which is a unique identifier assigned to each medical concept (see Fig. 4). We used the BRAT annotation tool37 to assign CUIs. BRAT, which is a visual tool, facilitated this process by allowing us to choose CUIs from a predefined, closed set specifically curated for this study, which greatly reduced ambiguity and ensured consistency in CUI assignment. We provide BRAT’s configuration files in a GitHub repository (see the data availability section. Where additional clarification was needed, we used the UMLS Metathesaurus browser to retrieve possible matches for ambiguous terms and selected the most contextually appropriate CUI based on the document’s content and clinical context. Assigning concept codes avoided redundancy and inconsistency in data analysis and interpretation and enabled linking the toxicities over time. Additionally, normalizing to UMLS concept codes has the benefit that many EHR systems and data registries recognize these codes, allowing for seamless integration of our pipeline into EHRs. The mapping resulted in more than 15 concepts, as presented in Fig. 5.

The corresponding UMLS CUI code was assigned to each toxicity.

Number of annotated (ground-truth) toxicity mentions in all reports.

Classification models

Pre-trained language models (PLMs) have significantly advanced NLP by providing a robust framework for understanding and generating human language10. These models learn rich representations for language understanding through pre-training on large text corpora, making them effective for various NLP tasks. Depending on the domain of their pre-training corpus (general text, medical text, etc.), language models can gain an understanding of the domain terminology38. PLMs are often fined-tuned on target tasks (supervised training) to learn task-specific representations, further boosting their performance.

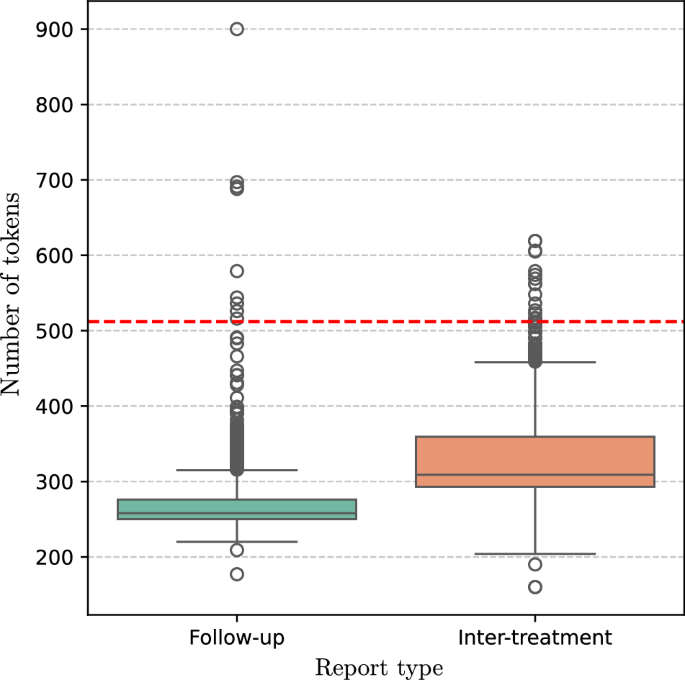

PLMs such as Clinical Longformer12 and Clinical BioBERT11, which are pre-trained on medical articles and clinical reports, as well as BERT10 pre-trained on general text, were used as the backbone for classification. All of these models are publicly available via the Huggingface library39. Assuming a text report comprises a sequence of T words 〈w1, w2, …, wT〉, the language models map the word to a sequence of vector representations 〈h1, h2, …, hT〉 where ({h}_{t}in {{mathbb{R}}}^{768}). In addition to the pre-training corpora, these models differ in the input length they can handle, i.e. the number of words in the text. BERT and Clinical BioBERT can only process text with a maximum of 512 words, while Clinical Longformer can handle 4098 words. Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of number of tokens for the two report types. The horizontal dashed line indicates the threshold (512 tokens) at which BERT and Clinical BioBERT truncated their input, i.e. the models do not see more than 512 tokens. Overall, 24 reports (both training and test) were truncated. In this study, two tasks were performed:

The horizontal dashed line shows the truncation threshold for BERT and Clinical bioBERT. Overall 24 reports were truncated by BERT and Clinical bioBERT.

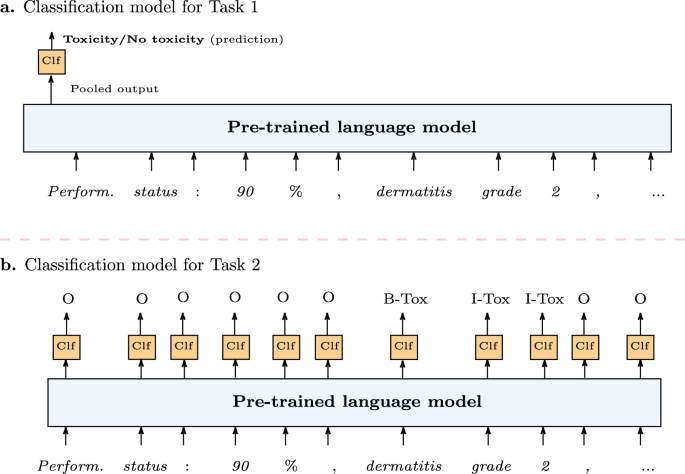

Task 1 (Toxicity detection)

This task involves classifying text reports to determine whether they contain mentions of toxicity rather than extracting particular toxicity mentions. This is particularly advantageous in scenarios where quick assessment of toxicities and the stratification of patients is necessary. All three language models provide a single vector representation (also called pooled output) of the whole text, which can be used for document-level (in our case, note-level) tasks. The representation was used as the input to a linear binary classifier as illustrated in Fig. 7a. The classifier was characterized by a (Win {{mathbb{R}}}^{768times 2}) which projected the pooled representation to 2 dimensions (the two possible classes).

a Toxicity classification (Task 1) where the language model provides a single representation of the whole text to be classified as positive (report contains toxicity) or negative (report dose not contain toxicity). b Toxicity extraction (Task 2) where the token representations provided by the language model are classified to determine the span of each toxicity mention.

Task 2 (Toxicity extraction and normalization)

Binary classification of clinical reports for the presence of toxicities (Task 1) provides a broad understanding of its occurrence but lacks granularity. We defined Task 2 as automatically extracting toxicity mentions. This task involves the automatic classification of text segments/spans (see Fig. 4) that mention toxicity within a report, which is more fine-grained compared to Task 1. Once the span of toxicity is determined, it is normalized to its UMLS CUI. The toxicity extraction was defined as a sequence labeling problem, which involves assigning a label to each element in a sequence, such as words in a sentence, based on the context and surrounding elements. We followed the BIO tag scheme where each token representation was labeled as O (Outside of a toxicity span), B-Tox (Beginning of a toxicity span), or I-Tox (Inside a toxicity span). The pre-trained language models provide vector representation for each word. Each representation is then used as the input to a linear multi-class classifier (see Fig. 7b) to predict one of the O, B-Tox, or I-Tox labels. The classifier was characterized by a (tilde{W}in {{mathbb{R}}}^{768times 3}) which projected the each token representation to 3 dimensions (the three possible tags). The identified spans were then classified for the UMLS CUI.

Training and evaluation

We trained the classification models on 80% of the patients and tested them on the remaining 20% as hold-out test data. The training and test sets were randomly selected with a uniform probability. An important consideration was ensuring that no patient documents were present in the test set if any of their reports were used in the training set. This practice helped maintain the integrity of the evaluation process by ensuring that the model’s performance was assessed on unseen data, thus providing a more realistic measure of its generalization capability.

The data partitioning resulted in 2842 reports as the training set and 668 reports as the test set. During the training process, the training loss/error for each task was calculated by cross-entropy loss. Both tasks were trained simultaneously, under a multi-task learning paradigm, by calculating a total loss L = L1 + L2, where L1 and L2 are the losses for Task 1 and Task 2, respectively. Multi-task learning allows the model to learn shared representations that enhanced performance across both tasks. This approach leads to a lightweight and efficient system, reducing computational overhead and simplifying deployment40. Additionally, the joint optimization fostered mutual reinforcement between the tasks, with toxicity detection providing context for extraction, and toxicity extraction refining detection. Empirical results showed that this design outperformed separate optimization, demonstrating improved generalization and practicality. Adam optimizer41 with a learning rate of 5e-4 was used to fine-tune the models. The models were trained for a maximum of 6 epochs with early stopping.

Two sets of document-level and span-level metrics were used to evaluate the models’ performance on the test data. For Task 1, well-established document-level metrics such as precision, recall, and F1 scores were used. Recall is the ratio of true positive predictions to the total number of actual positives:

where TP (true-positive) is the number of samples correctly classified as positive, and FN is the number of samples (with positive ground-truth label) that were incorrectly classified as negative. Recall measures of the ability of a model to capture all positive instances. High recall means that the model has fewer false negatives. Precision, on the other, is the ratio of true positive predictions to the total number of positive predictions:

where FP (false-positive) is the number of reports (with negative ground-truth label) that were incorrectly classified as positive. Precision measures the accuracy of positive predictions, and high precision means that the model has fewer false positives.

F1 score combines precision and recall using their harmonic mean:

The F1 score provides a balanced measure of a model’s performance by considering both false positives and false negatives. It is particularly useful in cases with an imbalanced class distribution or when both types of classification errors have significant implications.

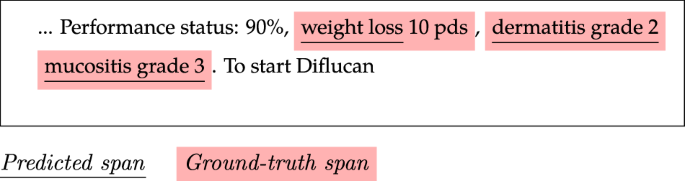

For Task 2, since labels are assigned for spans within a document, the evaluation metrics need to consider not just individual predicted labels, but also the alignment of predicted and ground-truth spans. Thus, for Task 2, overlapping and strict matching scores were used. These scores measure the ability of a model to correctly identify the boundaries of labeled spans that correspond to a toxicity mention. Overlapping scoring considers a prediction correct if it partially overlaps with a ground truth span, even if they do not match exactly. Strict match scoring, on the other hand, requires an exact match between the predicted and the ground truth spans, considering any deviation as an error, and thus is more strict. Figure 8 illustrates a sample report where ground-truth spans are indicated by red highlight and the predicted spans are indicated by underlined text. With overlapping scoring, all three predictions are considered correct, however, with strict scoring the first predicted span (weight loss) is an incorrect prediction since it does not completely cover the ground-truth span. In this example, the overlapping F1=1, while the strict F1=0.66.

With overlapping scoring, both precision and recall are 1 since all toxicity spans are detected, and all detected spans correspond to toxicity. With strict scoring, only two spans are considered correctly predicted.

Estimation of toxicity persistence

While the cohort included patients with multiple tumor types, the variability in clinical note frequency was moderate, as most patients adhered to standard follow-up schedules. We observed more detailed temporal patterns for patients with more frequent follow-ups due to clinical complications or additional treatments, which might influence the granularity of toxicity detection and time-to-event analyses. The data is inherently interval-censored since toxicities were assessed at discrete time points (in this study, at each radiotherapy appointment or follow-up visit). We accounted for variability in follow-up intervals by leveraging interval-censored methods, which are robust to such inconsistencies. Interval censoring occurs when the exact time of an event, in this case, the end/resolution of toxicity, is unknown. Still, it is known to have occurred within a certain interval. To account for the interval censoring, Turnbull’s algorithm was used to estimate the persistence of toxicities14,42. Turnbull’s algorithm is a nonparametric method specifically designed for analyzing interval-censored data, which aligns well with the nature of our dataset where the exact time of persistence of toxicities was not directly observed but was instead bounded within intervals. This algorithm is able to provide robust estimates of persistence probabilities without making strong assumptions about the underlying distribution of the data. This is particularly important in clinical settings, where the heterogeneity of patient responses to radiotherapy often violates parametric assumptions. By employing Turnbull’s algorithm, we ensured that our persistence estimates were both statistically sound and reflective of the observed variability in clinical practice.

When comparing time-to-event functions among different groups, a common test is the log-rank test, which relies on the assumption that event times are fully observed, which is inappropriate for interval-censored data. Instead, the asymptotic log-rank test is commonly used in this context43. This test is based on the asymptotic distribution of the log-rank statistic under the null hypothesis. An asymptotic log-rank test was used in the experiments to compare the persistence of toxicities among different groups.

While onset dates were occasionally mentioned in clinical notes, their inclusion cannot be consistently assumed. However, all clinical notes were associated with a writing date, which provides a definitive temporal reference. This ensures that each toxicity mention is tied to a specific point in time, even if it does not precisely reflect the true onset date. The starting time-point of a toxicity was defined as the date of the appointment when a toxicity was recorded in the notes. While the occurrence of the event (the end of toxicity) is known for most patients, a subset of cases are right-censored, which was taken into account when estimating the probability of persistence. Note that for a few patients, only a subset of their inter-treatment notes were available, meaning that the toxicity’s starting time is left-censored. The left-censoring for such few cases was relaxed, and the starting time-point of their toxicity was considered in the same manner as other patients, i.e., the first time-point mentioned in notes. The estimation of the persistence of toxicities, as well as the comparison of time-to-event functions, was performed in R using the Interval package?

Responses