An emerging role for neutrophils in the pathogenesis of endometriosis

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic gynecological disease affecting nearly 10% of reproductive-aged women (i.e., people who menstruate)1,2. Symptoms include intense pelvic pain with menstruation, chronic pelvic pain, increased incidence of infertility, heavy menstrual bleeding, and associations with autoimmune diseases and ovarian cancer3,4. This debilitating disease negatively impacts the woman’s quality of life leading to social and economic burdens to the United States costing more than $110 billion annually5,6. Regrettably, there is no definitive cure for endometriosis7,8. The current standard for diagnosis is using laparoscopic surgery to visualize the peritoneum for ectopic lesions which then must be histologically confirmed for at least two of the three hallmark characteristics9. The most common histological hallmarks for a positive diagnosis are the presence of endometrial glands, organized stroma, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages10. An additional histological hallmark being included for characterizing ectopic lesions is firbosis11. Current treatments primarily target endometriosis symptoms and are mainly palliative. These treatments include surgical excision, hormonal therapies, contraceptives, and pelvic physical therapy8,12. Surgical excision of lesions is associated with a decrease in disease-associated pain; however, many individuals still require additional surgical treatment within 3 years of their initial surgery7. Additional surgery often leads to comorbidities and additional medical complications from scar tissue and adhesions7. The peritoneal environment likely recognizes endometriosis lesions as a form of injury, and in response, forms bands of fibrotic scar tissue that adhere organs together and prevents normal movement within the peritoneum (i.e., a “frozen pelvis”). Post-surgical medical interventions such as hormonal therapies are frequently utilized to reduce the recurrence of pain following surgery, unfortunately, no conclusive evidence is currently available relating to the long-term efficacy for decreased symptoms using these preventative methods13.

Endometriosis is classified into at least three subtypes: superficial peritoneal, ovarian endometrioma, and deep infiltrating14. The subtypes are classified based on their location and the extent or depth of lesion infiltration15. Deep infiltrating lesions are considered as the most severe form of the disease16,17. Endometriosis research has heavily focused on established disease, whereas the initiation and early development of endometriosis has garnered far less attention. A current theory characterizes the peritoneal cavity as a local inflammatory environment whereby inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages, exacerbate and promote the pathogenesis of endometriosis18,19,20,21. To date, studies have primarily focused on the role of macrophages in promoting endometriosis, while much less is known on the role of neutrophils in disease pathogenesis, particularly, the role of neutrophils in the early stages of lesion development. Our review presents current knowledge of the functions of neutrophils, including phagocytosis, antigen presentation, cytokine release, immune cell recruitment, degranulation, and NETosis (i.e., the process of releasing neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)) in the pathogenesis of endometriosis and includes a discussion on current research gaps in the field.

Etiology of endometriosis

While the exact cause of endometriosis is unclear, lesions are known to be endometrial-derived tissue22,23,24 with murine model evidence demonstrating that endometrial tissue (and not mammary gland, bladder, or lung) forms the endometriotic lesions25. Although numerous theories surround the etiology of endometriosis, a leading hypothesis is via retrograde menstruation in which menstrual effluent containing viable endometrial tissue flows back through the oviduct and into the peritoneal cavity26,27. In support of this hypothesis, laparoscopic surgery performed during the perimenstrual period, 90% of women had menstrual blood in their peritoneal cavity27. In contrast, 15% of women with occluded oviducts exhibited evidence of blood in their peritoneal cavity27. While nearly all women experience retrograde menstruation, only 10% of reproductive aged women are diagnosed with endometriosis2,26 suggesting the etiology and pathobiology of endometriosis is highly multifaceted. An important caveat is that only humans and non-human primates develop endometriosis naturally28. Both species have an open reproductive system (i.e., the ovary is not connected to the oviduct) while all other mammalian species have a closed reproductive system (i.e., the ovary is surrounded by a bursa from the oviduct) and do not develop endometriosis naturally. The open reproductive tract allows for the retrograde flow to occur26; thus, retrograde menstruation is a leading theory of how menstrual effluent is found in the peritoneal cavity and how eutopic endometrial tissue can be displaced from the uterus to form ectopic endometrial lesions in the peritoneal cavity.

Besides viable endometrial cells, menstrual effluent contains a mixture of red and white blood cells associated with the late secretory phase of the menstrual cycle29,30. The effluent also contains a variety of proteins that are required as part of a healthy menstrual cycle29,30 that regulates the functions of proliferation, migration, apoptosis, hematopoiesis, and reproduction29. Menstrual effluent is distinct from peripheral blood and more closely resembles the uterine immune microenvironment31. Due to the inherent inflammatory nature of menstruation, a dysfunction of immune signaling during menstruation could disrupt normal processes resulting in an altered inflammatory state that would contribute to the development and/or exacerbation of endometriosis. Together, menstrual effluent studies are likely to be crucial to understanding the immune related components of lesion development and the pathogenesis of endometriosis.

Although endometriosis was previously considered only a hormonally driven disease32,33,34, it is now considered both an immune and a hormonally driven disease35. Further, insights into the functions of the immune system supports the likelihood that the initiation of the disease is regulated by immune interactions21,25. The exact early mechanisms of lesion formation are unknown, but the innate immune system is a strong contender as a contributor of the early effector cells in lesion development. Neutrophils are the first immune cells to respond to injury36, and in a mouse model of endometriosis as we cannot study lesion initiation in women, these cells were identified as the initial responding cell after the induction of endometriosis21, demonstrating the importance of neutrophils in the early stages of lesion formation. Shortly after the neutrophil response in the mouse model of endometriosis, macrophages respond in the early disease development and are implicated in the processes of tissue remodeling and the angiogenic processes associated with lesion establishment37,38. The exact interactions among all the different cell types (i.e., immune cells and epithelial and stromal cells from the endometrium) are in their infancy, but neutrophils and macrophages either work in conjunction with each other to promote lesion development or they play independent roles in the pathogenesis of the disease. While macrophages are beyond the scope of this review, strong reviews are published that focused on endometriosis and macrophages (See review by Hogg et al.39).

Immune cell responses are critical to maintaining a balanced and healthy uterine environment as these cells prevent injury and coordinate repair processes during menstruation40,41. Neutrophil, macrophage, and uterine natural killer cells are recruited to the endometrium during the late secretory phase; the influx of these cells establishes and primes the immune milieu prior to the onset of menses40. During menstruation, white blood cells account for ~40% of the cell volume with neutrophil, macrophage, and uterine natural killer cells accounting for the majority of the leukocyte volume40,42. The presence and importance of these white blood cells in menstrual effluent may indicate why these specific cells are recruited and further increase during the late secretory phase prior to the onset of menstruation41,43. Since the late secretory stage progresses to menses, these cells would comprise a majority of the immune cells which would enter the peritoneal cavity during retrograde menstruation. This increase of neutrophils just prior to the onset of menstruation is one key reason why these cells are of particular interest in endometriosis.

Neutrophil origin and functions

Neutrophils, polymorphonuclear phagocytic leukocytes, are often considered the first line of defense in inflammatory processes44. Neutrophils originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. An estimated one-hundred billion white blood cells are produced each day and neutrophils comprise about 70% of leukocytes in the human body45. The data supporting the lifespan of the neutrophil in circulation is quite variable and ranges from a half-life of 6–8 h45 to 5.4 days under homeostatic conditions46; thus, indicating neutrophil aging is a complex and dynamic process where the neutrophil lifespan greatly depends on responses to physiological stimuli or chronic inflammatory events47,48,49. Of note, in ex vivo studies, neutrophils typically do not survive longer than 24 h46, augmenting the complexities and arduous task of studying neutrophils in healthy and diseased states. Neutrophils mature in the bone marrow and enter blood vessels where they circulate until extravasation towards sites of injury via transendothelial migration50. In order to remove neutrophils from circulation or tissues, either macrophages clear aged, damaged, and apoptotic neutrophils via phagocytosis and/or neutrophils are returned to the bone marrow for clearance51. Maintaining a constant homeostatic balance of neutrophils is crucial for health; however, imbalances can exacerbate inflammatory conditions and/or infections. In a healthy state, the number of neutrophils is maintained as a constant homeostatic balance due to strict regulation of the number of eliminated and newly differentiated neutrophils52.

The differentiation and maturation of neutrophils is highly regulated by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (CSF3/GCSF) which serves as a regulator for neutrophil proliferation, differentiation, and maturation32. Interestingly, GCSF receptor expression on neutrophils is not sufficient alone for mobilization from the bone marrow indicating that GCSF indirectly affects neutrophils via trans-activating signals such as the downregulation of stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1/CXCL12) which acts as the ligand for the C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4)53, a chemokine receptor highly expressed on immature and aged neutrophils11. In addition to CSF3/GCSF and CXCR4, CXCR2 is another C-X-C chemokine receptor on the cell surface acting as a maturation signal for neutrophils. As neutrophils mature, signaling in concert with CXCR2 permits neutrophil mobilization from the bone marrow into the vasculature and circulation54,55. Neutrophil recruitment and chemotaxis are highly balanced and controlled by a CXCR2/CXCR4 axis54 with the cell surface expression of these receptors fluctuating over the lifetime of the neutrophil. As the neutrophil matures in the bone marrow, a switch occurs between the levels of CXCR2 and CXCR4 on their cell surface. Immature neutrophils express increased CXCR4 levels on their cell surface in the bone marrow, while increased CXCR2 levels are required to migrate out of the bone marrow55. As neutrophils age, they again begin to present higher levels of CXCR4 on their cell surface allowing them to migrate back to the bone marrow for clearance from the body54.

Neutrophils demonstrate these different phenotypic shifts (i.e., aging or maturing) which can occur over the course of a single day49. Hyper-segmentation of neutrophils, characterized by an increase of nuclear lobules, is the result of the aging process36. Aged neutrophils in circulation upregulate CXCR4 which allows re-entry into the bone marrow for clearance. This highly coordinated process is important for maintaining a homeostatic balance of neutrophil subtypes in the body55,56. For example, CXCR4high cells are often senescent and considered towards the end of their lifespan55. While the bone marrow plays a predominate role in neutrophil clearance, they are also cleared by the liver and spleen57. As detailed above, the C-X-C chemokine receptors, CXCR2 and CXCR4, are used as a method for differentiating between the life cycle stages of neutrophils. In addition to being a marker for age, CXCR4high neutrophils are also associated with reactive functions like NET formation is detailed below58.

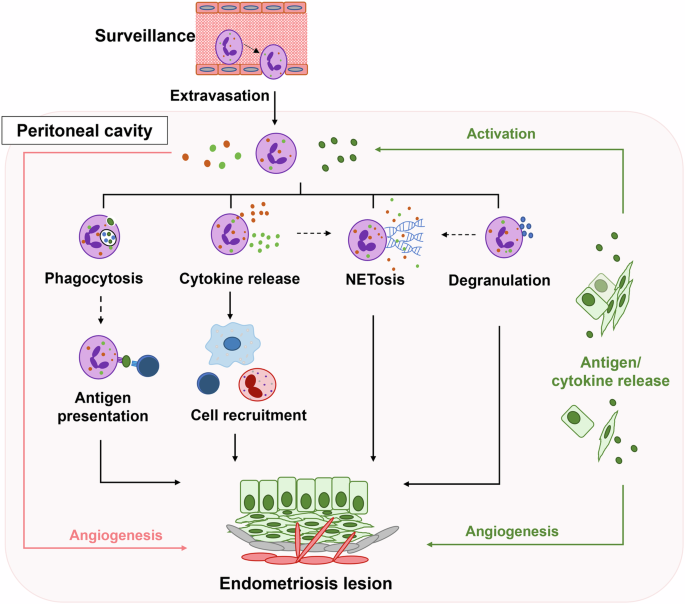

The neutrophil is a versatile cell type with a wide range of functions including surveillance, aiding in angiogenesis, phagocytosis, antigen presentation, releasing a plethora of cytokines, NETosis, and degranulation (Fig. 1). With a variety of functions, neutrophils are equipped to mitigate and exacerbate the inflammatory response at sites of injury. Although some of these functions have not yet been formally linked to the pathogenesis of human endometriosis, these cells are likely a contributing factor in inflammatory responses in the peritoneal cavity. By examining the functions of neutrophils, we propose to explain potential applications of neutrophils in disease by explaining their functions in similar inflammatory conditions while presenting current theories for their role(s) in endometriosis.

Neutrophils (purple) in circulation actively monitor for the presence of antigens or chemokines via surveillance. Upon receiving a chemotactic signal, neutrophils extravasate into the peritoneal cavity where antigens and cytokines from lesion cells (green) activate neutrophils to initiate and/or promote corresponding functions: angiogenesis, phagocytosis, antigen presentation, cytokine release, cell recruitment, NETosis (the process of releasing neutrophil extracellular traps), and degranulation. In combination, neutrophils (red line) and lesion cells (green line) promote angiogenesis through the release of proangiogenic factors. Following phagocytosis, neutrophils may participate in antigen presentation (dotted line) to T cells (dark blue) similar to other antigen presenting cells. Cytokine release triggers cell recruitment of T cells (dark blue), macrophages (light blue), and/or eosinophils (red) and may accompany NETosis (dotted line). Degranulation may occur in conjunction with NETosis (dotted line) or independently (solid line). Collectively, the activated neutrophil functions, both definitive (solid lines) and proposed (dotted lines), crosstalk with the lesion cells to promote a more permissive microenvironment in the peritoneal cavity resulting in lesion development and survival.

Neutrophils in endometriosis

Neutrophils are likely key components in the progression and pathogeny of endometriosis20,37,59. Once neutrophils arrive at an injury site, their activation responses depend on the source and severity of injury. Neutrophils are found altered in eutopic endometrium as well as ectopic lesion sites. In relation to the role of the CXCR2/CXCR4 axis, CXCR2 transcript levels increased in the eutopic endometrium of endometriosis patients compared to control patients18. This elevation of CXCR2 in endometriosis patients suggests increased neutrophil recruitment to the uterus which in turn would correspond with elevated levels in the peritoneal cavity and may provide insight into targeted treatments in the future. Indeed, in the peritoneal cavity of endometriosis patients, neutrophil numbers were increased compared to healthy control patients60,61. Furthermore, the endometriosis patients had increased levels of human neutrophil peptides 1, 2, and 3 which are also known as defensins60,61. The defensins elicit immune regulatory effects; however, their role in endometriosis is not well understood. Recent data suggest that the upregulation of human β-defensin-2 in ectopic endometrium may be due to TNF or IL1β, but the activity has not yet been directly linked to neutrophil-specific actions62. Additionally, the ability of neutrophils to respond to different activation signals was dysregulated in individuals with endometriosis suggesting an alteration in the induced proinflammatory response63. Other neutrophil dysfunctions, such as decreased phagocytosis, were also observed in endometriosis patients to further support the notion that neutrophils contribute to the pathogenesis or the lack of clearance of endometrial tissue in the peritoneal cavity64,65.

The activity of neutrophils in endometriosis has been largely understood using murine models as a method of examining lesion initiation and progression in relation to mechanism(s) of the disease development20,66. While limitations exist with these models and the induction process is different compared to human retrograde menstruation, these pre-clinical models provide basic mechanistic concepts that mimic aspects of human disease. While no model will ever perfectly recapitulate the pathogenesis of endometriosis, animal studies allow for an ethical approach to studying the initiation and progression of the disease without causing additional discomfort or harm to human subjects. An example of the usefulness of mice includes utilizing neutrophil depletion to modify the systemic and peritoneal immune microenvironment which contributed to understanding the modulation of angiogenic and pro-inflammatory factors in endometriosis20. In addition, neutrophils recruit macrophages which contributed to tissue remodeling processes once lesions were established in a mouse model of endometriosis37. Both neutrophils and macrophages produce proangiogenic factors which are ultimately necessary for the growth and stabilization of lesions37. Mouse translational studies are not only utilized for toxicity testing of potential therapeutics or drugs67,68,69,70,71, but can be beneficial to explicate potential mechanisms and roles of neutrophils in human endometriosis pathogenesis.

Neutrophil immunosurveillance initiates chemotaxis

One of the primary functions of neutrophils is to perform immunosurveillance where they circulate in the vasculature and transition between an adherent and non-adherent state until they encounter an antigen or activation signal where they will then migrate and extravasate to the site of injury36,72. Studying immune surveillance in endometriosis is rather complex due to temporal limitations and nonspecific interactions which can initiate the activation of cells. The numbers of neutrophils found in the peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis is higher compared to other leukocytes60, but the underlying initiating factors which activate neutrophils to migrate to the peritoneal cavity is largely unknown. Neutrophils do participate in immunosurveillance, but whether they are hypersensitive or receive an assault of cytokine and chemokine signals causing the initial migration is also unknown. Factors such as CXCL8/IL8, IL6, and C-X-C chemokines73,74,75 are potential culprits that may play a role in the initial shift from surveillance to extravasation and activation. Overall, the complex process is likely a combination of chemotactic factors that results in the inherent difficulty of identifying if “one” single instigator exists.

Neutrophils promote angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vessels76, is essential for the survival of new and developing tissues. The exact mechanism for the angiogenesis of developing endometriotic lesions is unclear, but evidence exists to support that neutrophils act as active effector cells in this process. In endometrial samples collected from normal cycling participants, neutrophils were the predominant immune cell that stained for VEGF, suggesting these cells actively regulate vascular proliferation in the endometrium77. Neutrophils release chemokines and cytokines like VEGF to promote angiogenesis by activating endothelial cells. The release of enzymes from neutrophils (e.g., elastase and cathepsin G) activate matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the stroma which leads to the breakdown and the process of tissue remodeling of the extracellular matrix40. Recent findings showed neutrophil functions were modified by IL6 and CSF3/GCSF via the STAT3 pathway resulting in an alteration of gene expression levels of angiogenic-related genes (i.e., MMP9, PROK2, and TNFSF10) to enhance angiogenesis78 which, in turn, could promote the survival of endometriotic lesions. MMPs and VEGF work in conjunction with one another by first degrading and/or remodeling the extracellular matrix allowing for neovascularization79. VEGF was found to be elevated in the peritoneal fluid and serum of patients with endometriosis80 supporting the hypothesis that active angiogenesis occurs in the peritoneal cavity microenvironment. Neutrophils are one of the predominant immune cells associated with VEGF and are most abundantly found in the late secretory phase and pre-menstrual phase of the menstrual cycle. A major function of the neutrophil in these phases is regulation of the endometrial vasculature77 which suggests that neutrophils are critical in the homeostasis of menstruation.

VEGF is crucial in periods of oxygen deprivation events like hypoxia81. Higher transcript levels of endocrine-gland-derived VEGF (EG-VEGF) was found in lesions compared to eutopic endometrium82 demonstrating that the lesions are actively attempting to survive by promoting angiogenesis. Typically, CXCL8/IL8 is considered a proinflammatory cytokine, but it can also be pro-angiogenic in function. Both VEGF and CXCL8/IL8 are elevated in ovarian endometriomas83 which indicates a connection to angiogenesis. Intriguingly, when neutrophils from healthy patients were exposed to peritoneal fluid isolated from endometriosis patients, the fluid induced the secretion of VEGF from the neutrophils84. However, when CXCL8/IL8 or TNF were blocked using antibody treatment ex vivo, the endometriosis patient-derived neutrophils still released VEGF indicating that patient-derived neutrophils are a source of peritoneal VEGF independent of CXCL8/IL8 and TNF84 suggesting that neutrophils from endometriosis patients may respond to or promote angiogenesis utilizing pathways or mechanisms that are not readily used by the neutrophils in healthy patients. Together, these findings suggest the plasticity of angiogenesis within endometriosis lesions is able to shift to CXCL8/IL8 independent pathways accommodating the needs of the peritoneal cavity. Additional endometriosis studies also demonstrated increased VEGF levels in the peritoneal fluid of endometriosis subjects compared to healthy controls85,86. Interestingly, in an oral contraceptive study, VEGF was elevated in the peritoneal cavity of patients with endometriosis; however, the use of birth control which is a common treatment modality for endometriosis did not affect the levels of VEGF87. Thus, angiogenesis of lesions does not appear to be directly influenced by hormonal treatments. The effects of hormonal therapies and treatments for endometriosis cause additional complications to elucidate the underlying mechanism(s) of angiogenesis and neutrophil function. Endometriosis lesions may be classified by coloration (e.g., red or black). In a study comparing red and black endometriosis lesions, red lesions were observed with elevated VEGF levels compared to black lesions, likely indicating that the red lesions are at an earlier stage of development than black lesions88. These findings also highlight that variability in VEGF levels will be observed based on lesion stage and activity (i.e., early implantation versus fully established). In general, the elevated VEGF levels identified in endometriosis patients and lesions suggests that angiogenesis is a key component of lesion survival and that neutrophils are likely effector cells for angiogenesis during lesion development.

A normal function of the uterus is tissue growth during endometrial repair post-menstruation—this process is strongly hypoxic and serves the local microenvironment as a stimulus for VEGF expression and subsequent neoangiogensis of the endometrium89. In patients with ovarian endometriomas, gene expression of hypoxia-inducible factor α (HIF-1/2A), VEGF, and protease-activated receptors 1 and 4 (PAR1 and PAR4) were considerably elevated over healthy control patients90. However, in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis, these difference were not observed90 suggesting that more established disease already has a well-established blood supply88 and would not require these factors or the factors may be cyclical in nature dependent on the stage of the menstrual cycle. As mentioned above, hypoxic events promote angiogenesis, but these events also serve as an inducer of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Thus, the hypoxic nature of menstruation likely acts as an inducer of the EMT found in lesion tissue91,92, but also supports hypoxia as an inducer of angiogenesis and cell migration. Hypoxia occurs in the endometrium during menstruation by inducing HIF1A, a process that is important for healthy repair and function during a healthy menses93. Individuals with heavy menstrual bleeding have decreased endometrial HIF1A during menstruation and have prolonged menstrual bleeding93 which may suggest that the inability to repair the endometrium properly during menstruation leads to a disruption of normal function. HIF1A is stabilized by the release of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) by neutrophils during NETosis94, thus linking neutrophil dysfunction to potential alterations in the hypoxic conditions during menstruation. In regard to the retrograde hypothesis, since HIF1A is naturally a part of menstruation, aberrant hypoxic function may induce mechanistic changes during menstrual flow modifying retrograde menstrual effluent resulting in an altered microenvironment inside of the peritoneal cavity permissive to lesion establishment93. In other organs like the lungs, hypoxia can increase degranulation and protease release in neutrophils95. Whether these similar functions occur in endometriosis has not yet been identified but may be an area of scientific interest. While the exact mechanism of how neutrophils influence angiogenesis is unclear, the supporting evidence suggests neutrophils mediate angiogenesis directly through secretion of VEGF and their interactions with hypoxic factors.

Neutrophil phagocytosis is reduced in endometriosis

Phagocytosis by neutrophils and other effector cells is the primary method of clearance used for antigens and cellular debris to maintain homeostatic balance in the body. Sites of inflammation often enhance phagocytosis; however, a defect in this process can alter how neutrophils respond to inflammation (i.e., inducing additional NETs or increased cytokine release). Macrophages are often distinguished as the main phagocytic cell type which ingest apoptotic and non-apoptotic neutrophils96. However, macrophages may not be the only cells involved in neutrophil clearance—findings in mice show neutrophil cannibalism, the act of neutrophils phagocytosing other neutrophils, has been observed in lung inflammatory conditions when macrophages do not sufficiently quell or regulate the neutrophil inflammatory response97. While this mechanism is not yet characterized in humans, it could be an area of future study for inflammatory conditions like endometriosis. Additionally, while neutrophil autophagy (e.g., self-cannibalism or self-ingestion) is known to occur in human neutrophils98, this function is also not yet linked to endometriosis. These phagocytic processes pose for an intriguing area of endometriosis research to determine if these functions occur and whether they alter clearance of immune cells to alter the proinflammatory responses in the peritoneal cavity during pathogenesis. A compelling study examined the phagocytic activity of neutrophils from peripheral blood and found that patients with endometriosis had reduced phagocytic function64,99, but their neutrophil phagocytic function increased 1-week post operatively and was comparable to the phagocytic function of non-endometriosis controls64. Additionally, the same research group, found that pre-operative, peripheral blood neutrophils from endometriosis patients demonstrated improved phagocytic function when exposed to plasma from individuals without endometriosis. On the other hand, when healthy control neutrophils were exposed to plasma from patients with endometriosis, phagocytic function decreased65 suggesting that the cytokine and/or chemokine composition in plasma directly negatively alters neutrophil phagocytic function in endometriosis. Together these findings suggest that ectopic lesions in endometriosis patients initiate a local altered immune response (i.e., immune suppressive) which may lead to reduced function in circulating neutrophils resulting in a systemic inflammatory dysfunction64.

The altered phagocytic function of neutrophils could result in the inability to clear ectopic endometrial tissue, thus, increasing the likelihood of lesion development and a chronic pro-inflammatory environment in the peritoneal cavity. In contrast to neutrophils where heme is an activator of phagocytosis via oxidative burst100, in macrophages elevated concentrations of heme in peritoneal fluid of endometriosis patients impairs their phagocytic activity101 which suggests that during events like retrograde menstruation, neutrophil function may or may not be a compensatory mechanism for impaired macrophage phagocytic activity. Whether heme activates neutrophils in the peritoneal cavity in endometriosis or neutrophils are desensitized to heme resulting in reduced clearance of viable endometrial tissue is unknown, but these functions are compelling research avenues worth delving into deeper to understand the mechanisms in the initiation phase of endometriosis. Overall, these changes in phagocytic activity could indicate that neutrophils, macrophages, and other immune cells are desensitized to the heme found in menstrual blood leading to a phagocytic dysfunction in endometriosis. Although many differences exist between peripheral blood and menstrual effluent, an underlying difference in activity may be present in the overall phagocytic activities in neutrophils from individuals with endometriosis. Further studies are necessary to determine the characteristic differences in phagocytosis to understand whether cytokines, heme, or some other unknown factor(s) is the direct cause of this dysfunction found specifically in patients with endometriosis.

Neutrophils serve as antigen presenting cells

More recent findings suggest that neutrophils possess the ability to act as antigen-presenting cells, specifically in response to CD4+ memory T cells. Although monocytes and dendritic cells show a higher affinity and efficiency for antigen presentation, human and primate neutrophils have demonstrated the ability to adapt and participate in the antigen presenting processes102,103. When human neutrophils phagocytose red blood cells, they possess the ability to express MHC II along with the primary costimulatory molecules (e.g., CD40 and CD80) required for antigen presentation to T cells103. In humans, subsets of T memory cells have been identified as participating in surveillance functions in the female reproductive tract and these cells are regulated throughout the stages of the menstrual cycle through a CCR5 signaling pathway104. Additionally, in highly inflammatory events like sepsis, aged neutrophils are able to induce CD4+ T cells to exacerbate the inflammatory environment105. While the presence of these subpopulations of memory T cells in lesions nor their interactions between neutrophils and CD4+ T cells have not been elucidated in endometriosis, the communication of how the neutrophils communicate with T cells via antigen presentation in endometriosis would be a compelling area of research. The ability of antigen presentation by neutrophils in endometriosis pathogenesis is an undeveloped area of research that would help refine the role of neutrophil migration and/or lymphocyte responses directly in lesion development.

Neutrophil associated cytokines are modulated in endometriosis

Neutrophils, as well as other immune cells, release cytokines to regulate inflammatory responses to recruit additional cells, initiate angiogenesis, or trap foreign materials that promote injury72,106,107. CXCL8/IL8, a chemokine produced by neutrophils, plays a role in the chemotaxis, release of lysosomal enzymes, and upregulation of adhesion molecules and initiation of oxidative burst in neutrophils108,109,110. CXCL8/IL8 was found to be abnormally regulated and elevated in the peritoneal cavity of women with endometriosis111,112,113. Interestingly, in a study of infertility, endometriosis patients had increased IL6 and CXCL8/IL8 in their peritoneal fluid and also had increased CXCL8/IL8 in their serum114. The increase of CXCL8/IL8 in the serum suggests a systemic inflammatory reaction from neutrophils that is not confined to the ectopic lesions or the peritoneal cavity environment. When neutrophil cultures were treated with peritoneal fluid from endometriosis patients, the levels of CXCL8/IL8 and CXCL10 were elevated115 indicating neutrophils not only produce but are a source of these cytokines in the peritoneal fluid. In a surgical excision study, 2 weeks following surgery, the levels of CXCL8/IL8 in plasma decrease significantly116 suggesting that communication between lesions and immune cells regulate the inflammatory state not only of the microenvironment, but systemically as well. A unique and recent hypothesis regarding the menstrual cycle is that the levels of CXCL8/IL8 do not vary and are not affected by the cyclical variation of the menstrual cycle; however, this finding was debunked by the ability of estrogen which enhances cell responsiveness to IL1 in endometriosis lesions and in turn, IL1 induces CXCL8/IL8117 which aids in explaining the elevated CXCL8/IL8 levels found in endometriosis patients. Furthermore, progesterone also stimulates CXCL8/IL8 which indicates that the sex steroid hormones promote inflammatory responses indirectly by elevating CXCL8/IL8 mRNA and protein73. Even though IL1 is not a direct recruiter of neutrophils118, this cytokine leads to the increase of other chemokine ligands which attract neutrophils to the site of injury119. However, neutrophils do not express estrogen receptor alpha or progesterone receptor77, indicating that neutrophil responses are indirectly hormonally driven.

IL6 is a unique chemokine which acts as both a pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory regulator120,121, and has been observed to be elevated in the peritoneal cavity of women with endometriosis87. In mice, IL6 is elevated in the first few days of disease initiation, but drops after lesion establishment21 suggesting this cytokine is influential in the early stages of lesion development. Upon inflammatory progression, IL6 can promote neutrophilia, an increase of neutrophils in peripheral blood, and can control trafficking of leukocytes74 which could lead to an overabundance of neutrophils and a dysregulated inflammatory microenvironment. The increase of IL6 in patients with endometriosis leads to the hypothesis that this cytokine is important to lesion development and survival.

In comparison to the role of IL6 in lesion development, in the early stages of injury, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are released. DAMPs directly recruit neutrophils to sites of injury122; however, with endometriosis no external wound or infection is present. The endometriosis microenvironment may be considered a sterile inflammatory event suggesting that neutrophils may also be recruited to sites of lesion establishment by DAMPs. In ovarian endometriomas, neutrophil responses possessed an immunosuppressive function and an extended lifespan59 due to the induction of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), a controller of T cell responses and immune tolerance59, which suppressed the proliferation and function of T cells in endometriosis patients. Importantly, regulatory T cells are deficient in endometriosis123 and can produce the potent neutrophil chemoattractant CXCL8/IL8124. Whether the regulatory T cells directly contribute to the dysregulation of normal immune functions and the ability to properly regulate the immune inflammatory response in the case of neutrophil recruitment is unclear. Together, the reduction of T cells may possibly stem from neutrophil dysfunction in endometriosis patients. Additional clinical research is needed to determine the neutrophil effects on T cell regulation in endometriosis and the direct role that DAMPs play in activation of neutrophils specifically in patients with endometriosis.

Neutrophil extracellular trap formation is elevated in endometriosis

Early NET formation was initially considered a form of apoptosis or necrosis and was named accordingly as it was often accompanied by cell death125,126. NETosis, or the process of NET formation, occurs via two pathways: a lytic or cell death pathway and a non-lytic pathway. The lytic pathway involves chromatin decondensation accompanied with the loss of cell polarization where chromatin is expelled via plasma membrane rupture. The non-lytic formation of NETs involves the excretion of chromatin and is accompanied by degranulation. In the non-lytic form of NETosis, the cell is viable and provides conventional neutrophil effector functions127 such as the formation of anucleated cytoplasts that ingest and clear foreign substances128. One variation from apoptosis is that NETosis does not require activation of caspases128,129. Although the initiation process of NETosis is not entirely understood in diseases such as endometriosis, one hypothesis is that NETosis is centered around mitochondrial induction. Neutrophil mitochondria produce ROS via NADPH oxidase in glycolysis. The ROS produced via the mitochondria are speculated to be responsible for the initiation of NETosis130,131. Current research areas related to neutrophils are focused on the function of NETs in the progression of endometriosis. NETs are increased in circulation in endometriosis patients as observed in venous blood collected at time of laparoscopic surgery19,132 with the highest levels quantified in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis132. In peritoneal fluid, the presence and quantification of NETs was elevated in endometriosis patients compared to patients without the disease19. Interestingly, in the same study, neutrophils from control patients treated with peritoneal fluid from patients with endometriosis did not stimulate NET production19 indicating that NETs released in endometriosis may be due to an endometriosis-specific dysfunction in neutrophils and not due to the response to the cytokines or products found in the peritoneal fluid. Increased NET levels in endometriosis patients indicates the likelihood of a more chronic inflammatory status19,20 which may contribute to a more systemic effect as evidenced by the increase of NETs in the circulation19,132. Myeloperoxidase (MPO), a byproduct of NETs, was elevated in ovarian endometriomas in comparison to eutopic endometrium20, illustrating that the release of NET byproducts in the lesion microenvironment promotes a more inflammatory state compared to the eutopic endometrium. MPO is also suspected as a contributing infertility factor in endometriosis because the follicular fluid of patients with endometriosis undergoing IVF treatments contained MPO levels that were significantly higher than in control follicular fluid133, and is thus proposed as a potential target in the treatment of infertility in endometriosis. Utilizing a surface plasmon resonance imaging biosensor, cathepsin G levels, another byproduct of NETs, were observed to be doubled in the endometrium from patients with endometriosis as compared to the control group134 which again demonstrates the inflammatory microenvironment of endometrium in endometriosis patients is amplified or exacerbated in comparison to control samples. In menstruation, neutrophils positive for elastase, an indicator of NETosis, peak during menstruation135. The increase in elastase expressing neutrophils may explain the increase of NETs in peritoneal fluid of endometriosis patients due to the introduction of these neutrophils via retrograde menstruation. NETs found in the peritoneal fluid indicate this process is linked in either the cell-based initiation or exacerbation of the disease19. Clearance of NETs can be taxing for the body, but in many cases, macrophages are able to clear them. The inherent difficulty in NET clearance may promote lesion survival and attachment due to a delay in tissue removal136. Although the majority of the information surrounding NETs in endometriosis is quantitative in respect to byproducts of the process, mechanistic studies to further examine the effect of NETs on endometriosis and the exacerbation of disease is greatly needed.

Neutrophil degranulation may exacerbate inflammatory responses

Neutrophils have an altered response or are desensitized to activation signals in endometriosis which may affect the release of additional granules required to achieve an essential physiological response in endometriosis patients63. Currently, it is unclear whether neutrophil activation is the result of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from the lesion sites or whether neutrophils are recruiting each other in a positive feedback loop63. Neutrophilic granules contain a multitude of proteins which are released in response to various stimuli44. Lactoferrin, an anti-inflammatory protein, and myeloperoxidase, a proinflammatory enzyme, are indicators of neutrophil activation—both of these proteins are found in neutrophil granules137. Lactoferrin was elevated in the peritoneal fluid of endometriosis stages II, III, and IV138 indicating a potential neutrophil degranulation release. Interestingly, anti-lactoferrin antibodies were found in serum of endometriosis patients prior to surgical excision of lesions, but levels decreased post-operatively139 which may point to a dysfunction in the degranulation of neutrophils leading to an autoimmune type response.

MPO and other NET byproducts can be released either during degranulation with or without the release of NETs (these molecules are described in the NET section). Epithelial neutrophil-activating peptide (ENA-78/CXCL5), a chemoattractant and activator or neutrophil function involved in degranulation, was elevated in the peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis and is expressed in both ectopic glandular and stromal cells140. In addition, the levels of this chemokine correlated to disease stage and high pain severity140,141. Elevated levels of ENA-78/CXCL5 in the peritoneal fluid demonstrates that degranulation does play a role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis and leads to increased peritoneal inflammation. As mentioned above, defensins, released during degranulation, are elevated in peritoneal fluid in patients with endometriosis61. Thus, these findings in conjunction with each other indicate that changes in degranulation from neutrophils is evident in patients with endometriosis; however, gaps remain in our understanding of how these functions may influence early lesion development, iron metabolism, and/or advanced disease pathogenesis.

Challenges of translating mouse models to human disease

The use of murine and animal models has immensely benefited endometriosis research with mechanistic studies67,68,69,70,71, especially in the early stages of lesions development which cannot be easily or ethically conducted in humans. Although there are differences in endometriosis pathobiology between human patients and mouse models, murine models have demonstrated the usefulness of studying the initiation and pathogenesis of disease. An important caveat with using mouse models is to acknowledge that no model can recapitulate all aspects of endometriosis pathogenesis due to the differences in the immune system of mice, mouse models are useful tools for examining prospective mechanisms which may translate into human diagnostics or treatments. An area of variance between humans and mice is that mouse neutrophils are often identified by the cell surface marker, Ly6G, whereas human neutrophils do not possess Ly6G on their surface and require more complex strategies for identification142. In human peripheral blood, neutrophils account for about 70% of the white blood cell composition45 and while mice contain less peripheral blood neutrophils, the neutrophil is still the highest granulocyte in abundance143,144. Mice and humans can also differ in granule composition within the neutrophil itself: differences include murine neutrophils do not make defensins145 and the amount of MPO levels under normal conditions are higher in humans146 which can pose a challenge when studying NETs and degranulation. Defensins (e.g., human neutrophil peptides 1, 2, and 3) are elevated in humans with endometriosis61 which poses an issue when trying to elucidate the role and/or mechanism of these molecules if utilizing a mouse model that is not humanized. Additionally, mice lack the gene coding for CXCL8/IL8, but do have homologs to human CXCR2, CXCL2, and CXCL144,45 which can still be utilized to study chemotaxis of neutrophils. The lack of CXCL8/IL8 cannot be studied in endometriosis rodent models, but this chemokine has been an area of interest in human studies due to its elevation in the peritoneal fluid of endometriosis patients112. With the use of humanized or transgenic mice, this hurdle could be surmounted to observe the effect of CXCL8/IL8 on neutrophils in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. However, mouse models have managed to explore neutrophil depletion and knockout studies to further understand their role in lesion development and targets have included Ly6G20,147 and CXCR2148. Although, the mouse immune system has some variances from the human immune system, these models provide an ethical approach to understanding mechanisms of lesion development and, when paired with human data, may lead to improved diagnostics and treatments for women. Despite differences between these two species, mouse models are essential for understanding the mechanistic functions of neutrophils in endometriosis and how they exacerbate disease.

Neutrophil targeted therapies and diagnostics

Currently, endometriosis treatments are more palliative in nature8 and treatments which provide longer relief from symptoms are desperately needed. Understanding neutrophils and other innate immune cells are a key component to finding better endometriosis treatments. A promising approach may be to block or deplete neutrophil numbers to reduce disease severity. Neutrophil depletion causes a delay in the repair and breakdown of the endometrium149. Since lesions are composed of endometrial-like tissue, this process may be used as a target for either prevention or elimination of endometriotic lesions. In mice, neutrophil depletion did decrease the number of lesions, but did not significantly affect the lesion weight147. The reduction of lesion number indicates that there may have been attachment issues early in the lesion initiation process. If the early attachment and angiogenesis phases are targeted, then prevention or reduction of lesion development may be possible. While it is not possible to deplete neutrophils in human patients, alternative possibilities could be to try and block or reduce neutrophil recruitment during menstruation. In another study, retinoic acid reduced VEGF mRNA and protein150,151. Retinoic acid is synthesized in endometrial cells when exposed to progesterone which lends to a proposal of retinoid being beneficial as a treatment for endometriosis, but retinoic acid will cause complications during pregnancy and would be not advisable151. Additionally, reducing angiogenic factors may lead to the inability of lesions to attach, but the teratogenic effects of retinoids may reduce the likelihood of this treatment in the future. One proposed predictive diagnostic to evaluate the prevalence of recurrence of endometriotic lesions is the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio152 or to assess this ratio as a general risk factor for endometriosis153. This metric has not been implemented in a clinical setting, but with further consideration and testing may lead to a diagnostic. In a primate model, an CXCL8/IL8 antibody, AMY109, was a treatment to reduce CXCL8/IL8 and was successful in reducing inflammation and fibrosis154. This antibody may present potential for an CXCL8/IL8 targeted treatment. A further area of consideration is to determine whether immunosurveillance is defective and what steps are needed to correct this defect in endometriosis patients. Some suggest that targeting neutrophil degranulation would act to treat endometriosis by reducing inflammation155. Examining menstrual fluid for variations in immune components will likely lead to non-invasive diagnosis and/or treatment possibilities. A dire need exists for better and non-invasive treatments and whether neutrophils may be the key has yet to be determined.

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a debilitating disease which negatively impacts the lives of affected patients, both mentally and physically. The early initiation of the disease is influenced by immune cell interactions. Although less is known about some of the early interactions, mouse models have been illuminating for determining early disease initiation mechanisms. During each menstrual period, retrograde menstruation provides a potential opportunity to expose the peritoneal cavity to immune cells and viable endometrial tissues which may promote an exacerbation and progression of the disease. The mechanisms of how lesions are formed is unclear, but recent research shows that immune cell responses are heavily implicated in disease pathogenesis and may be the key to understanding this disease. Neutrophils are the first responders and likely play a key role in early responses to lesion formation and clearance of retrograde menstruation. The release of VEGF is one way that neutrophils can promote angiogenesis and lesion development. Although other cells like macrophages aid in the remodeling and neovascularization, the effects of neutrophils are still a factor in the early stages. Cytokines like IL6 and CXCL8/IL8 are found at abnormal levels in endometriosis. Both of these cytokines affect neutrophil recruitment and alter the peritoneal cavity microenvironment. Currently, determining which cytokine has the greatest influence on neutrophils is difficult due to crosstalk and temporal limitations of studying neutrophil surveillance. In addition, NETosis may be a large factor in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. With more NETs found in endometriosis patients, evidence supports that the functions may differentiate healthy women from women with endometriosis. Whether NETs are the primary driving force or whether the multifactorial actions of neutrophils work in conjunction to promote disease, it is apparent that neutrophils are an understudied aspect of early disease initiation and progression, thus highlighting the critical need to determine all of the roles of this important cell type. Determining the specifics of neutrophil and immune functions in endometriosis may provide insight into potential non-surgical diagnoses or treatment targets. Neutrophils, along with other immune cells, may be the key to finding the potential biomarkers needed for earlier diagnoses and understanding this complex disease.

Responses